Rush Hour (1998 film)

| Rush Hour | |

|---|---|

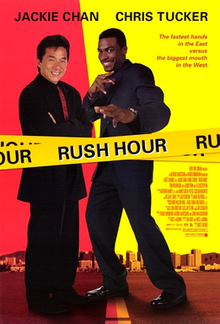

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Brett Ratner |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Ross LaManna |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Adam Greenberg |

| Edited by | Mark Helfrich |

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States[2] |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $33–35 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $244 million[3] |

Rush Hour is a 1998 American buddy cop action comedy film directed by Brett Ratner and written by Jim Kouf and Ross LaManna from a story by LaManna. It stars Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker as mismatched police officers who are assigned to rescue a Chinese diplomat's abducted daughter. Tom Wilkinson, Chris Penn and Elizabeth Peña play supporting roles.

Released on September 18, 1998, the film received positive reviews from critics and has grossed over $244 million worldwide. Its box office commercial success led to two sequels: Rush Hour 2 (2001) and Rush Hour 3 (2007).

Plot

[edit]On the last day of British rule of Hong Kong on June 30, 1997, Detective Inspector Lee of the Royal Hong Kong Police Force leads a raid at the wharf, hoping to arrest the unidentified, anonymous crime lord Juntao. He finds only Sang, Juntao's right-hand man, who escapes in a boat. Lee recovers numerous Chinese cultural treasures stolen by Juntao, which he presents as a farewell victory gift to his departing superiors, Chinese consul Solon Han and British police commander Thomas Griffin.

Two months later after Han takes up his new diplomatic post in Los Angeles, Han's daughter Soo Yung is kidnapped by Sang while on her way to school. Han calls Lee to assist in the case, but the FBI, fearing that Lee's involvement could cause an international incident, pawns him off on the LAPD. Detective James Carter, a talented but obnoxious LAPD officer who is disliked by the rest of his precinct for his self-aggrandizing attitude, is tricked into "babysitting" Lee as punishment for botching a sting operation. When Carter finds out, he decides to solve the case. Carter takes Lee on a sightseeing tour, keeping him away from the embassy while contacting informants about the kidnapping. Lee gets into trouble when Carter tells him to follow his lead, resulting in Lee calling a black bartender the N-word, not knowing it is offensive. Several black patrons attack Lee as a result, forcing him to defeat them. Carter tries to prevent Lee from leaving him but Lee makes his own way to the Chinese Consulate, where Han and the FBI await news about his daughter. While arguing with Special Agent in Charge Warren Russ, Carter unwittingly negotiates with Sang, arranging a $50 million ransom drop.

The FBI traces the call to a warehouse, where a team of agents are killed by plastic explosive. Spotting Sang nearby, Lee and Carter give chase but he escapes, dropping the detonator. Carter's colleague, LAPD bomb expert Tania Johnson, traces it to Clive Cobb, the man arrested by Carter in the earlier botched sting operation. Lee presses Clive into revealing his business relationship with Juntao, whom he met at the Foo Chow restaurant in Chinatown. Clive is initially unwilling to speak to the duo but Lee shows him a picture of Soo Yung, causing him to relent. Lee then begins to earn Carter's trust. Carter goes to the restaurant alone and sees a surveillance video of Juntao carrying Soo Yung into a van. Lee arrives and saves Carter from Juntao's syndicate, but they are taken off the case as the FBI blames them for the botched ransom drop, with Lee sent back to Hong Kong. However, Carter refuses to give up and appeals to Johnson for assistance to sneak on board Lee's plane, where he persuades the Hong Kong detective to help stop Juntao together.

Griffin later involves himself in the case, revealing more about the HKPF's past with Juntao's syndicate, and implores Han to pay the ransom to avoid further bloodshed. At the opening of a Chinese art exhibition at the Los Angeles Convention Center, overseen by Han and Griffin, the now $70 million ransom is delivered, and Carter, Lee, and Johnson enter disguised as guests. Carter orders the guests to evacuate for safety, angering the FBI, but Lee catches Griffin accepting a remote for the detonator from Sang. Lee and Johnson realize Griffin is Juntao when Carter recognizes him from the Chinatown surveillance tape. Griffin threatens to detonate a bomb vest attached to Soo Yung and demands that the ransom be paid in full, as compensation for the priceless Chinese artifacts which Lee recovered in his raid. Juntao's men start a shootout with the FBI while Carter sneaks out, locates Soo Yung in the van, and drives it into the building within range of Griffin, preventing him from setting off the vest.

Johnson gets the vest off Soo Yung, while Griffin heads to the roof with the bag of money. Lee takes the vest and pursues Griffin, while Carter shoots Sang dead in a gunfight and saves Russ. Lee has a brief altercation with Griffin that culminates in both dangling from the rafters. Griffin, holding on to the vest, falls to his death when its straps are torn, but when Lee falls, Carter catches him with a large flag. Han and Soo Yung are reunited and Han sends Carter and Lee on vacation to Hong Kong as a reward. Before Carter leaves, agents Russ and Whitney offer him a position in the FBI, which he mockingly refuses, proudly stating he is LAPD. Carter boards the plane with Lee, who annoyingly starts singing Edwin Starr's "War" off-key. A desperate Carter yells for a stewardess, demanding that she give him another seat.

Cast

[edit]- Jackie Chan as Chief Inspector Lee, a top Hong Kong cop skilled in martial arts who comes to Los Angeles to help his friend find his kidnapped daughter.

- Chris Tucker as Detective James Carter, a fast-talking street-smart LAPD Detective originally assigned by the FBI to babysit Lee and keep him out of their investigation.

- Tom Wilkinson as Thomas Griffin/Juntao, a British diplomat and colleague of Han's who is secretly a top crime lord in Hong Kong.

- Tzi Ma as Consul Solon Han, Soo Yung's father and a Hong Kong diplomat who has just moved to Los Angeles.

- Ken Leung as Sang, Juntao's second in command.

- Elizabeth Peña as Detective Tania Johnson, an aspiring bomb squad technician in the LAPD who helps Carter rescue Soo-Yung.

- Mark Rolston as FBI Special Agent Warren Russ

- Rex Linn as FBI Agent Dan Whitney, Russ's partner

- Chris Penn as Clive Cod, a small time arms dealer who was arrested by Carter in a botched sting operation.

- Philip Baker Hall as Captain Bill Diel, Carter's supervisor. He gives Carter the FBI assignment as punishment for a botched undercover sting operation.

- Julia Hsu as Soo-Yung Han, Consul Han's daughter who is kidnapped by a criminal organization. She is also a martial arts student of Lee's.

Other cast members include John Hawkes as Carter's informant "Stucky", Clifton Powell as Carter's cousin Luke, Barry Shabaka Henley as prison guard Bobby, Roger Fan and George Cheung as Soo-Yung's bodyguards, Gene LeBell as a taxi driver, and Frances Fong (in her final film role) as a socialite. Jackie Chan Stunt Team members Ken Lo, Nicky Li Chung-chi, Chan Man-ching and Andy Cheng appear as Juntao's henchmen.

Production

[edit]Rush Hour began as a spec script written in 1995 by screenwriter Ross LaManna. The screenplay was sold by LaManna's William Morris agent Alan Gasmer to Hollywood Pictures, a division of the Walt Disney Company, with Arthur Sarkissian attached as producer. After attaching director Brett Ratner and developing the project for more than a year with producers including Sarkissian, Jonathan Glickman and Roger Birnbaum, Disney Studios chief Joe Roth put the project into turnaround, citing concerns about the $34 million budget, and Jackie Chan's appeal to American audiences. Several studios were interested in acquiring the project. New Line Cinema was confident in Ratner, having done Money Talks with him, so they made a hard commitment to a budget and start date for Rush Hour.[5]

Martin Lawrence, Wesley Snipes, Chris Rock, Eddie Murphy and Dave Chappelle were considered for the role of Detective James Carter; Murphy turned down the role to do Holy Man instead while Snipes turned down the role in favor of Blade, which was also for New Line Cinema.[6][7][8] Chan wanted Lawrence for the role, but he turned it down due to a low offer.[9]

After the success of Rumble in the Bronx, Ratner wanted to put Chan in a buddy-cop movie, not as a co-star or sidekick but on equal footing with an American star. Ratner flew to South Africa where Chan was filming and pitched the film. A few days later Chan agreed to star and not long after flew to Los Angeles and met Chris Tucker, the latter actor who ended up taking the role as Detective James Carter.[10]

Ratner credited Tucker with getting his first feature film Money Talks and thought Tucker and Chan would make a great team.[11] Filming began on November 30, 1997.[12] Shooting took place mainly in locations around the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, including the Los Angeles Convention Center, Grauman's Chinese Theater, Greystone Mansion, Ennis House, and Long Beach Airport. The opening sequence was shot in Hong Kong.

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Rush Hour opened at No. 1 in September 1998 at the North American box office, with a weekend gross of $33 million. It surpassed The First Wives Club to have the highest September opening weekend and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to have the biggest opening weekend for a New Line Cinema film.[13] The film would hold latter record until the following June when Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me took it.[14] Rush Hour would continue to hold the September record for three more years until it was surpassed by Sweet Home Alabama in 2002.[15] Overall, it would top the box office for two weeks before getting displaced by Antz.[16] Rush Hour grossed over $140 million in the US and $103 million in the rest of the world, for a total worldwide gross over $244 million.[3][17]

Critical response

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, Rush Hour holds an approval rating of 62% based on 77 reviews and an average score of 6.2/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "While it won't win any awards for originality, the combustible chemistry between its stars means Rush Hour hits just as hard on either side of the action-comedy divide."[18] On Metacritic, the film received a weighted average score of 61 out of 100 based on 23 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[19] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[20]

Roger Ebert praised both Jackie Chan, for his entertaining action sequences without the use of stunt doubles, and Chris Tucker, for his comical acts in the film, and how they formed an effective comedic duo.[21] Joe Leydon of Variety called it "a frankly formulaic but raucously entertaining action comedy". Leydon is critical of the editing, saying that it "works against Chan by breaking up the flow of his frenzied physicality."[22] Charles Taylor of Salon.com is critical of Hollywood misusing Jackie Chan: "Chan is a one-of-a-kind performer: Bruce Lee crossed with Donald O'Connor in the "Make 'em Laugh" number from Singin' in the Rain. Hollywood needs to stop treating him as if he were one of those fondue sets given as wedding gifts in the '70s: a foreign novelty shoved in a closet due to absolute cluelessness about what to do with it."[23]

Michael O'Sullivan of The Washington Post calls the film a "misbegotten marriage of sweet and sour" and says, "The problem is it can't make up its mind and, unlike Reese's Peanut Butter Cups, the sharply contrasting flavors of these ingredients only leave a bad taste in the customer's mouth." O'Sullivan says Tucker is miscast, the script "perfunctory and sloppy", and the direction "limp, lethargic".[24] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a grade "C−" and was critical of the buddy comedy, saying, "The two characters barely even have a relationship; they're a union of demographics—the "urban" market meets the slapstick-action market."[25]

Chan has expressed dissatisfaction with the film: "I didn’t like the movie. I still don’t like the movie." Chan continued: "I don’t like the way I speak English, and I don’t know what Chris Tucker is saying". Although he respects the box-office success of Rush Hour, Chan said he preferred the films he made in his native Hong Kong because they delivered more fight scenes: "If you see my Hong Kong movies, you know what happens: Bam bam bam, always Jackie Chan-style, me, 10 minutes of fighting."[26][27][28]

Cultural influence

[edit]Rush Hour was the catalyst for the creation of the review-aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes. Senh Duong, the website's founder and a Jackie Chan fan, was inspired to create the website after collecting all the reviews of Chan's Hong Kong action films as they were being released in the United States. In anticipation of Rush Hour, Chan's first major Hollywood crossover, he coded the website in two weeks and the site went live shortly before the film's release.[29][30]

Sequels

[edit]A sequel, Rush Hour 2, which was primarily set in Hong Kong, was released in 2001. A third film, Rush Hour 3, which was primarily set in Paris, was released on August 10, 2007.[31] Tucker earned $25 million for his role in the third film and Chan received the film's distribution rights in Asia.[27]

In 2007, before the release of Rush Hour 3, Ratner was optimistic about making a fourth film and potentially having it set in Moscow.[32] In 2017, Chan agreed to a potential script for Rush Hour 4 after years of turning down scripts.[33][34][35]

Music

[edit]Edwin Starr's "War" was used as the ending theme for the film.

The film's soundtrack features the hit single "Can I Get A..." by Jay-Z, Ja Rule and Amil, as well as tracks by Flesh-n-Bone, Wu-Tang Clan, Dru Hill, Charli Baltimore and Montell Jordan.

The official soundtrack album was certified platinum on January 21, 1999.

Awards

[edit]- 1999 ALMA Awards

- Winner: Outstanding Actress in a Feature Film (Elizabeth Peña)

- 1999 BMI Film and TV Awards

- Winner: BMI Film Music Award (Lalo Schifrin)

- 1999 Blockbuster Entertainment Awards

- Winner: Favorite Duo- Action/Adventure (Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker)

- Nomination: Favorite Supporting Actress- Action/Adventure (Elizabeth Peña)

- 1999 Bogey Awards (Germany)

- Winner: Bogey Awards in Silver

- 1999 Golden Screen (Germany)

- Winner: Golden Screen

- 1999 Grammy Awards

- Nomination: Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or for Television (Lalo Schifrin)

- 1999 NAACP Image Awards

- Nomination: Outstanding Lead Actor in a Motion Picture (Chris Tucker)

- 1999 Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards (United States)

- Nomination: Favorite Movie Actor (Blimp Award) (Chris Tucker)

- 1999 MTV Movie Awards

- Winner: Best On-Screen Duo (Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker)[36]

- Nomination: Best Comedic Performance (Chris Tucker)

- Nomination: Best Fight (Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker) (For the fight against the Chinese gang)

- Nomination: Best Movie Song (Jay-Z) (For Can I Get A...)

Home media

[edit]| Release date | Country | Classification | Publisher | Format | Language | Subtitles | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 26, 1999 | United States | PG-13 | New Line Home Video | NTSC | English | None | [37] | |

| October 18, 1999 | United Kingdom | 12 | Entertainment in Video | PAL | English | None | [38] |

| Release date | Country | Classification | Publisher | Format | Region | Language | Sound | Subtitles | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2, 1999 | United States | PG-13 | New Line Home Video | NTSC | 1 | English | Unknown | English | Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1 (16:9) | [39] |

| October 1, 1999 | United Kingdom | 12 | Entertainment in Video | PAL | 2 | English | Unknown | English | Aspect Ratio: 1.77:1 (16:9) | [40] |

| February 14, 2000 | Australia | M | Roadshow Entertainment | PAL | 4 | English | Dolby Digital 5.1 Dolby Digital 2.0 |

English | Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1 (16:9) Dolby Digital Trailer: Canyon |

UMD

[edit]| Release date | Country | Classification | Publisher | Format | Region | Language | Sound | Subtitles | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 1, 2005 | United Kingdom | 12 | Entertainment in Video | PAL | 2 | English | Unknown | English | [41] | |

| January 3, 2006 | United States | PG-13 | New Line Home Entertainment | NTSC | 1 | English | Unknown | English | [42] |

| Release date | Country | Classification | Publisher | Format | Region | Language | Sound | Subtitles | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 11, 2010 | United Kingdom | 15 | Warner Home Video | PAL | Free | English | Unknown | English | Aspect Ratio: 2.40:1 (16:9) | [43] |

| December 7, 2010 | United States | PG-13 | New Line Home Entertainment | NTSC | Free | English | Unknown | English | Aspect Ratio: 2.40:1 (16:9) | [44] |

See also

[edit]- Buddy cop film

- List of films set in Hong Kong

- List of films set in Los Angeles

- Jackie Chan filmography

References

[edit]- ^ "Rush Hour". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ "Rush Hour (1998)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Rush Hour". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved June 25, 2006.

- ^ "Rush Hour (1998)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (October 6, 1998). "Studios Were in Passing Lane for 'Rush Hour'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ "Martin Lawrence & Wesley Snipes almost played Chris Tucker's role in Rush Hour | EPISODE 18 - YouTube". YouTube. January 28, 2021. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "The Lost Roles of Dave Chappelle". April 5, 2012. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "The Lost Roles of Eddie Murphy". April 7, 2011. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Martin Lawrence Says He Turned Down Offer to Costar with Jackie Chan in 'Rush Hour': 'Not Enough Money'".

- ^ Alex Pappademas (October 3, 2017). "Jackie Chan's Plan to Keep Kicking Forever". GQ. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Clement, Nick (January 19, 2017). "Crowd-Pleasing Hits Pepper Walk of Fame Honoree Brett Ratner's Resume". Variety. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Cox, Dan (November 5, 1997). "Wilkinson merges into 'Rush Hour'". Variety. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ^ Vitucci, Clarie (September 22, 1998). "It's 'Rush Hour' at weekend box office". The Associated Press. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 79. Archived from the original on May 14, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Feelin' Pretty Groovy: 'Austin Powers,' the Spy Who's No. 1". Los Angeles Times. June 14, 1999.

- ^ "Moviegoers Make It a 'Sweet' September". Los Angeles Times. October 1, 2002. Archived from the original on November 5, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "Animated "Antz' crawls to top in box office debut".

- ^ Wolk, Josh (September 28, 1998). "Losers Take All". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Rush Hour (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "Rush Hour (1998)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 12, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 18, 1998). "Rush Hour". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2006.

- ^ Leydon, Joe (September 21, 1998). "Review: 'Rush Hour'". Variety. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Charles Taylor (September 18, 1998). "Hong Kong Hollywood". Salon. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Michael O'Sullivan (September 18, 1998). "'Rush Hour': Slow Going". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 10, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Owen Glieberman (September 25, 1998). "Rush Hour". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Hugh Hart (September 8, 2002). "His Career Is No Stunt". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Associated Press (September 30, 2007). "FOXNews.com – Jackie Chan Admits He Is Not a Fan of 'Rush Hour' Films – Celebrity Gossip | Entertainment News". Fox News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007.

- ^ Clarence Tsui (December 13, 2012). "Jackie Chan Calls for Curbs on Political Freedom in Hong Kong". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

I dislike Rush Hour the most, but ironically it sold really well

- ^ "20 Years Later, Rush Hour Is Still a Buddy-Cop Gem". Rotten Tomatoes. September 18, 2018. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ Semley, John (2018). Hater: On the Virtues of Utter Disagreeability. Penguin Books. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-7352-3617-2. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ "Chan Says Tucker Holding Up Rush Hour 3". The Associated Press. July 10, 2005. Archived from the original on April 26, 2006. Retrieved June 25, 2006.

- ^ ""Rush Hour 4" is Set in Moscow". WorstPreviews.com. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Shirley Li (October 6, 2017). "Jackie Chan teases that 'Rush Hour 4' is close to being a reality". EW. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Chris Tilly (August 13, 2014). "Jackie Chan Downplays Talk of Rush Hour 4 and Drunken Master 3". IGN. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "Jackie Chan Says Rush Hour 4 Is Happening, but There's a Catch". E! Online. October 5, 2017. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "1999 MTV Movie Awards". MTV. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Rush Hour [VHS] (1998). Amazon.com. ISBN 0-7806-2371-1.

- ^ "Rush Hour [VHS] [1998]". Amazon.co.uk. October 15, 1999. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ Rush Hour (New Line Platinum Series) (1998). amazon.com. ISBN 0-7806-2514-5.

- ^ "Rush Hour [DVD] [1998]". amazon.co.uk. October 1999. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ "Rush Hour [UMD Mini for PSP]". amazon.co.uk. September 2005. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ "Rush Hour [UMD for PSP] (1998)". Amazon. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ "Rush Hour [Blu-ray] [1998] [Region Free]". amazon.co.uk. October 11, 2010. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ "Rush Hour [Blu-ray] (1998)". Amazon. December 7, 2010. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

External links

[edit]- 1998 films

- 1998 action comedy films

- 1998 martial arts films

- Films about Chinese Americans

- American action comedy films

- American buddy cop films

- American martial arts films

- Fictional portrayals of the Los Angeles Police Department

- Films about kidnapping

- Kung fu films

- 1990s martial arts comedy films

- 1990s police comedy films

- American police detective films

- Culture of Los Angeles

- Triad films

- New Line Cinema films

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in Hong Kong

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Hong Kong

- Films set in 1997

- Films about child abduction in the United States

- Films scored by Lalo Schifrin

- Films directed by Brett Ratner

- Films with screenplays by Jim Kouf

- Films produced by Roger Birnbaum

- Films about the Federal Bureau of Investigation

- 1990s buddy cop films

- Rush Hour (franchise)

- Chinese-language American films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- American buddy comedy films

- 1990s Hong Kong films

- English-language crime comedy films

- English-language action comedy films

- English-language thriller films

- English-language buddy comedy films