Wood turtle

| Wood turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Glyptemys |

| Species: | G. insculpta

|

| Binomial name | |

| Glyptemys insculpta (Le Conte, 1830)

| |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

| |

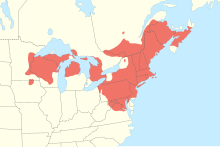

The wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) is a species of turtle in the family Emydidae. The species is native to northeastern North America. The genus Glyptemys contains only one other species of turtle: the bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii). The wood turtle reaches a straight carapace length of 14 to 20 centimeters (5.5 to 7.9 in), its defining characteristic being the pyramidal shape of the scutes on its upper shell. Morphologically, it is similar to the bog turtle, spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata), and Blanding's turtle (Emydoidea blandingii). The wood turtle exists in a broad geographic range extending from Nova Scotia in the north (and east) to Minnesota in the west and Virginia in the south. In the past, it was forced south by encroaching glaciers: skeletal remains have been found as far south as Georgia.

It spends a great deal of time in or near the water of wide rivers, preferring shallow, clear streams with compacted and sandy bottoms. The wood turtle can also be found in forests and grasslands, but will rarely be seen more than several hundred meters from flowing water. It is diurnal and is not overtly territorial. It spends the winter in hibernation and the hottest parts of the summer in estivation.

The wood turtle is omnivorous and is capable of eating on land or in water. On an average day, a wood turtle will move 108 meters (354 ft), a decidedly long distance for a turtle. Many other animals that live in its habitat pose a threat to it. Raccoons are over-abundant in many places and are a direct threat to all life stages of this species. Inadvertently, humans cause many deaths through habitat destruction, road traffic, farming accidents, and illegal collection. When unharmed, it can live for up to 40 years in the wild and 58 years in captivity.

The wood turtle belongs to the family Emydidae. The specific name, insculpta, refers to the rough, sculptured surface of the carapace. This turtle species inhabits aquatic and terrestrial areas of North America, primarily the northeast of the United States and parts of Canada.[5] Wood turtle populations are under high conservation concerns due to human interference of natural habitats. Habitat destruction and fragmentation can negatively impact the ability for wood turtles to search for suitable mates and build high quality nests.

Taxonomy

[edit]Formerly in the genus Clemmys, the wood turtle is now a member of the genus Glyptemys, a classification that the wood turtle shares with only the bog turtle.[6] It and the bog turtle have a similar genetic makeup, which is marginally different from that of the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata), the only current member of the genus Clemmys.[7] The wood turtle has undergone extensive scientific name changes by various scientists over the course of its history.[6] Today, there are several prominent common names for the wood turtle, including sculptured tortoise, red-legged tortoise, and redleg.[6]

Although no subspecies are recognized, there are morphological differences in wood turtles between areas. Individuals found in the west of its geographic range (areas like the Great Lakes and the Midwest United States) have a paler complexion on the inside of the legs and underside of the neck than ones found in the east (places including the Appalachian Mountains, New York, and Pennsylvania).[8] Genetic analysis has also revealed that southern populations have less genetic diversity than the northern; however, both exhibit a fair amount of diversity considering the decline in numbers that have occurred during previous ice ages.[9]

Description

[edit]

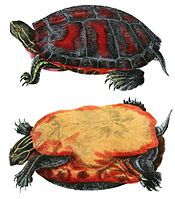

The wood turtle usually grows to between 14 and 20 centimeters (5.5 and 7.9 in) in straight carapace length,[10] but may reach a maximum of 23.4 centimeters (9.2 in).[6][8] It has a rough carapace that is a tan, grayish brown or brown in color, with a central ridge (called a keel) made up of a pyramidal pattern of ridges and grooves.[10] Older turtles typically display an abraded or worn carapace. Fully grown, it weighs 1 kilogram (2.2 lb).[11] The wood turtle's karyotype consists of 50 chromosomes.[8]

The larger scutes display a pattern of black or yellow lines. The wood turtle's plastron (ventral shell) is yellowish in color[10] and has dark patches. The posterior margin of the plastron terminates in a V-shaped notch.[6] Although sometimes speckled with yellowish spots, the upper surface of the head is often a dark gray to solid black. The ventral surfaces of the neck, chin, and legs are orange to red with faint yellow stripes along the lower jaw of some individuals.[6] Seasonal variation in color vibrancy is known to occur.[8]

At maturity, males, which reach a maximum straight carapace length of 23.4 centimeters (9.2 in), are larger than females, which have been recorded to reach 20.4 centimeters (8.0 in).[8] Males also have larger claws, a larger head, a concave plastron, a more dome-like carapace, and a longer tail than females.[12] The plastron of females and juveniles is flat while in males it gains concavity with age.[11] The posterior marginal scutes of females and juveniles (of either sex) radiate outward more than in mature males.[12] The coloration on the neck, chin, and inner legs is more vibrant in males than in females, which display a pale yellowish color in those areas.[8] Hatchlings range in size from 2.8 to 3.8 centimeters (1.1 to 1.5 in) in length (straight carapace measurement).[12] The plastrons of hatchlings are dull gray to brown. Their tail usually equals the length of the carapace and their neck and legs lack the bright coloration found in adults.[10] Hatchlings' carapaces also are as wide as they are long and lack the pyramidal pattern found in older turtles.[12]

The eastern box turtle (Terrapene c. carolina) and Blanding's turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) are similar in appearance to the wood turtle, and all three live in overlapping habitats. However, unlike the wood turtle, both Blanding's turtle and the eastern box turtle have hinged plastrons that allow them to completely close their shells. The diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) has a shell closely resembling the wood turtle's; however its skin is gray in color, and it inhabits coastal brackish and saltwater marshes.[10] The bog turtle and spotted turtle are also similar, but neither of these has the specific sculptured surface found on the carapace of the wood turtle.[13]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

The wood turtle is found in most New England states, Nova Scotia, west to Michigan, northern Indiana and Minnesota,[8] and south to Virginia. Overall, the distribution is disjunct with populations often being small and isolated. Roughly 30% of its total population is in Canada.[11] It prefers slow-moving streams containing a sandy bottom and heavily vegetated banks. The soft bottoms and muddy shores of these streams are ideal for overwintering. Also, the areas bordering the streams (usually with open canopies[4] ) are used for nesting. Spring to summer is spent in open areas including forests, fields, bogs, wet meadows, and beaver ponds. The rest of the year is spent in the aforementioned waterways.[10]

The densities of wood turtle populations have also been studied. In the northern portion of its range (Quebec and other areas of Canada), populations are fairly dilute, containing an average of 0.44 individuals per 1 hectare (2.5 acres), while in the south, over the same area, the densities varied largely from 6 to 90 turtles. In addition to this, it has been found that colonies often have more females than males.[7]

In the western portion of its range, wood turtles are more aquatic.[14] In the east, wood turtles are decidedly more terrestrial, especially during the summer. During this time, they can be found in wooded areas with wide open canopies. However, even here, they are never far from water and will enter it every few days.[15]

Evolutionary history

[edit]In the past, wood turtle populations were forced south by extending glaciers. Remains from the Rancholabrean period (300,000 to 11,000 years ago) have been found in states such as Georgia and Tennessee, both of which are well south of their current range.[8] After the receding of the ice, wood turtle colonies were able to re-inhabit their customary northern range[16] (areas like New Brunswick and Nova Scotia).[8]

Nesting behavior

[edit]The wood turtle is oviparous. It produces offspring by laying eggs, and does not provide parental care outside of nest-building. Thus, the location and quality of nesting sites determine the offspring survival and fitness; so females invest significant time and energy into nest site selection and construction. Females select nest sites based on soil temperature (preferring warmer temperature nest sites), but not soil composition.[17] Average nest size is four inches wide and three inches deep. Also, females build nests in elevated areas in order to avoid flooding and predation. After laying eggs, female wood turtles will cover the nest with leaves or dirt in order to hide the unhatched eggs from predators, and then the female will leave the nest location until the next mating season. Nesting sites can be used by the same female for multiple years.[5] Because nest building occurs along rivers, females tend to spend more time along river areas, compared to male turtles.[18]

Ecology and behavior

[edit]

During the spring, the wood turtle is active during the daytime (usually between about 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m.)[15] and will almost always be found within several hundred metres of a stream. The early morning and late afternoon are preferred foraging periods.[15] Throughout this season, the wood turtle uses logs, sandy shores, or banks to bask in sunlight.[19] In order to maintain its body temperatures through thermoregulation, it spends a considerable amount of time basking, most of which takes place in the late morning and late afternoon. The wood turtle reaches a peak body temperature of 37 °C (99 °F) after basking. During times of extreme heat, it has been known to estivate. Several reports mention individuals resting under vegetation, fallen debris and in shallow puddles. During the summer, the wood turtle is considered a largely terrestrial animal.[4] At night, its average body temperature drops to between 15 and 20 °C (59 and 68 °F)[20] and it will rest in small creeks or nearby land (usually in areas containing some sort of underbrush or grass).[15]

During colder weather, the wood turtle stays in the water for a larger percentage of the time.[20] For this reason, during the winter months (and the late fall and early spring) it is considered an aquatic turtle.[4] November through February or March is spent in hibernation at the bottom of a small, flowing river. The wood turtle may hibernate alone or in large groups. During this period, individuals bury themselves in the thick mud at the bottom of the river and rarely move. During hibernation, it is vulnerable to flash floods. Emergence does not occur until March or sometimes April, months that mark the beginning of its activation period (males are typically more active than females at this time).[20]

Males are known to be aggressive, with larger and older turtles being more dominant. Larger males rank higher on the social hierarchy often created by wood turtle colonies. In the wild, the submissive turtle is either forced to flee, or is bombarded with physical abuses, which include biting, shoving, and ramming. Larger and more dominant males will sometimes try to remove a subordinate male while he is mating with a female. The defender will, if he does not successfully fight for his position, lose the female to the larger male. Therefore, among males, there is a direct relationship between copulation opportunities and social rank.[21] However, the outcome of encounters between two turtles is more aggression-dependent than size-dependent. The wood turtle that is more protective of his or her area is the victor. Physical bouts between wood turtles (regardless of sex) increases marginally during the fall and spring (times of mating).[22]

The wood turtle is omnivorous, feeding mainly on plant matter and animals both on land and in water. It eats prey such as beetles, millipedes, and slugs. Also, wood turtles consume specific fungi (Amanita muscaria and Leccinum arcolatum), mosses, grasses, various insects, and also carrion.[23] On occasion, it can be seen stomping the ground with alternating hits of the left and right front feet. This behavior imitates the vibrations caused by moles, sometimes causing earthworms to rise to the surface where they quickly become easy prey.[24] When hunting, the wood turtle pokes its head into such areas as dead and decaying logs, the bottoms of bushes, and in other vegetation. In the water, it exhibits similar behavior, searching algae beds and cavities along the sides of the stream or river.[23]

Many different animals are predators of or otherwise pose a threat to the wood turtle. They include snapping turtles, raccoons, otters, foxes, and cats. All of these species destroy unhatched eggs and prey upon hatchlings and juveniles. Several animals that often target wood turtle eggs are the common raven and coyote, which may completely destroy the nests they encounter. Evidence of predatory attacks (wounds to the skin and such) are common on individuals, but the northern populations tend to display more scarring than the southern ones. In addition to these threats, wood turtles also suffer from leech infestations.[25]

Movement

[edit]The wood turtle can travel at a relatively fast speed (upwards of 0.32 kilometers per hour (0.20 mph)); it also travels long distances during the months that it is active. In one instance, of nine turtles studied, the average distance covered in a 24-hour period was 108 meters (354 ft), with a net displacement of 60 meters (197 ft).[26]

The wood turtle, an intelligent animal, has homing capabilities. Its mental capacity for directional movement was discovered after the completion of an experiment that involved an individual finding food in a maze. The results proved that these turtles have locating abilities similar to that of a rat. This was also proved by another, separate experiment. One male wood turtle was displaced 2.4 kilometers (1.5 mi) after being captured, and within five weeks, it returned to the original location. The homing ability of the wood turtle does not vary among sexes, age groups, or directions of travel.[22]

Life cycle

[edit]

The wood turtle takes a long time to reach sexual maturity, has a low fecundity (ability to reproduce), but has a high adult survival rate. However, the high survival rates are not true of juveniles or hatchlings. Although males establish hierarchies, they are not territorial.[4] The wood turtle becomes sexually mature between 14 and 18 years of age. Mating activity among wood turtles peaks in the spring and again in the fall, although it is known to mate throughout the portion of the year they are active. However, it has been observed mating in December.[27] In one rare instance, a female wood turtle hybridized with a male Blanding's turtle.[28]

The courtship ritual consists of several hours of 'dancing,' which usually occurs on the edge of a small stream. Males often initiate this behavior, starting by nudging the female's shell, head, tail, and legs. Because of this behavior, the female may flee from the area, in which case the male will follow.[27] After the chase (if it occurs), the male and female approach and back away from each other as they continually raise and extend their heads. After some time, they lower their heads and swing them from left to right.[19] Once it is certain that the two individuals will mate, the male will gently bite the female's head and mount her. Intercourse lasts between 22 and 33 minutes.[27] Actual copulation takes place in the water,[19] between depths between 0.1 and 1.2 meters (0 and 4 ft). Although unusual, copulation does occur on land.[27] During the two prominent times of mating (spring and fall), females are mounted anywhere from one to eight times, with several of these causing impregnation. For this reason, a number of wood turtle clutches have been found to have hatchlings from more than one male.[21]

Nesting occurs from May until July. Nesting areas receive ample sunlight, contain soft soil, are free from flooding, and are devoid of rocks and disruptively large vegetation.[21] These sites however, can be limited among wood turtle colonies, forcing females to travel long distances in search of a suitable site, sometimes a 250 meters (820 ft) trip. Before laying her eggs, the female may prepare several false nests.[28] After a proper area is found, she will dig out a small cavity, lay about seven eggs[19] (but anywhere from three to 20 is common), and fill in the area with earth. Oval and white, the eggs average 3.7 centimeters (1.5 in) in length and 2.36 centimeters (0.93 in) in width, and weigh about 12.7 grams (0.45 oz). The nests themselves are 5 to 10 centimeters (2.0 to 3.9 in) deep, and digging and filling it may take a total of four hours. Hatchlings emerge from the nest between August and October with overwintering being rare although entirely possible. An average length of 3.65 centimeters (1.44 in), the hatchlings lack the vibrant coloration of the adults.[28] Female wood turtles in general lay one clutch per year and tend to congregate around optimal nesting areas.[19]

The wood turtle, throughout the first years of its life, is a rapid grower. Five years after hatching, it already measures 11.5 centimeters (4.5 in), at age 16, it is a full 16.5 to 17 centimeters (6.5 to 6.7 in), depending on sex. The wood turtle can be expected to live for 40 years in the wild, with captives living up to 58 years.[23]

The wood turtle is the only known turtle species in existence that has been observed committing same-sex intercourse.[29] Same-sex behavior in tortoises is known in more than one species.

The wood turtle exhibits genetic sex determination, in contrast to the temperature-dependent sex determination of most turtles.[30]

Mating system

[edit]Specific mating courtship occurs more often in the Fall months and usually during the afternoon hours from 11:00 to 13:00 when many of the turtles are out in the population feeding.[31] Mating is based on a male competitive hierarchy where a few higher ranked males gain the majority of mates in the population. Male wood turtles fight to gain access to female mates. These fights involve aggressive behaviors such as biting or chasing one another, and the males defend themselves by retreating their heads into their hard shells. The higher ranked winning males in the hierarchy system have a greater number of offspring than the lower ranked male individuals, increasing the dominant male's fitness.[32] Female wood turtles mate with multiple males and are able to store sperm from multiple mates.[32] Although the mechanism of sperm storage is unknown for the Wood Turtle species, other turtle species have internal compartments that can store viable sperm for years. Multiple mating ensures fertilization of all the female's eggs and often results in multiple paternity of a clutch, which is a common phenomenon exhibited by many marine and freshwater turtles.[32] Multiple paternity patterns have been made evident in wood turtle populations by DNA fingerprinting. DNA fingerprinting of turtles involves using an oligonucleotide probe to produce sex specific markers, ultimately providing multi-locus DNA markers.[33]

Conservation

[edit]

Despite many sightings and a seemingly large and diverse distribution, wood turtle numbers are in decline. Many deaths caused by humans result from: habitat destruction, farming accidents, and road traffic. Also, it is commonly collected illegally for the international pet trade. These combined threats have caused many areas where they live to enact laws protecting it.[7] Despite legislation, enforcement of the laws and education of the public regarding the species are minimal.[34]

For proper protection of the wood turtle, in-depth land surveys of its habitat to establish population numbers are needed.[35] One emerging solution to the highway mortality problem, which primarily affects nesting females,[14] is the construction of under-road channels. These tunnels allow the wood turtle to pass under the road, a solution that helps prevent accidental deaths.[7] Brochures and other media that warn people to avoid keeping the wood turtle as a pet are currently being distributed.[35] Next, leaving nests undisturbed, especially common nesting sites and populations, is the best solution to enable the wood turtle's survival.[36]

While considered nationally as threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), the wood turtle is listed as vulnerable within the province of Nova Scotia under the Species at Risk Act. The species is highly susceptible to human land use activities, and special management practices for woodlands, rivers and farmland areas as well as motor vehicle use restrictions and general disruption protection during critical times such as nesting and movement to overwintering habitat is closely monitored.[37] Since 2012, the Clean Annapolis River Project (CARP) has provided research and stewardship for this species including the identification of crucial habitats, distribution and movement estimation, and outreach.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ van Dijk, P.P.; Harding, J. (2016) [errata version of 2011 assessment]. "Glyptemys insculpta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T4965A97416259. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T4965A11102820.en. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 185. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. S2CID 87809001.

- ^ a b c d e Bowen & Gillingham 2004, p. 4

- ^ a b "American Wood Turtle". www.psu.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Bowen & Gillingham 2004, p. 5

- ^ a b c d Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 262

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 251

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 252

- ^ a b c d e f NHESP 2007, p. 1

- ^ a b c COSEWIC 2007, p. iv

- ^ a b c d Bowen & Gillingham 2004, p. 6

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, pp. 252–253

- ^ a b Bowen & Gillingham 2004, p. 8

- ^ a b c d Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 253

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 250

- ^ Hughes, Geoffrey N.; Greaves, William F.; Litzgus, Jacqueline D. (2009-09-01). "Nest-Site Selection by Wood Turtles (Glyptemys insculpta) in a Thermally Limited Environment". Northeastern Naturalist. 16 (3): 321–338. doi:10.1656/045.016.n302. ISSN 1092-6194. S2CID 83603614.

- ^ Parren, Steven (2013). "A twenty-five year study of the Wood Turtle in Vermont: Movements, Behaviors, Injuries, and Death". Herpetological Conservation and Biology. 1: 176–190.

- ^ a b c d e NHESP 2007, p. 2

- ^ a b c Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 254

- ^ a b c Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 258

- ^ a b Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 256

- ^ a b c Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 260

- ^ Catania, Kenneth C. (2008-10-14). "Worm Grunting, Fiddling, and Charming—Humans Unknowingly Mimic a Predator to Harvest Bait". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3472. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3472C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003472. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2566961. PMID 18852902.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 261

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 255

- ^ a b c d Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 257

- ^ a b c Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 259

- ^ Biol. Exuberance: Wood Turtle - Bagemihl (1999 AD), page 657

- ^ Badenhorst, Daleen; Stanyon, Roscoe; Engstrom, Tag; Valenzuela, Nicole (2013-04-01). "A ZZ/ZW microchromosome system in the spiny softshell turtle, Apalone spinifera, reveals an intriguing sex chromosome conservation in Trionychidae". Chromosome Research. 21 (2): 137–147. doi:10.1007/s10577-013-9343-2. ISSN 1573-6849. PMID 23512312. S2CID 254379278.

- ^ Walde, Andrew (2003). "Ecological aspects of a Wood Turtle, Glyptemys insculpta, population at the northern limit of its range in Quebec". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 117 (3): 377–388. doi:10.22621/cfn.v117i3.739.

- ^ a b c Pearse, Devon (2001). "Turtle Mating Systems: Behavior, Sperm Storage, and Genetic Paternity". Journal of Heredity. 92 (2): 206–211. doi:10.1093/jhered/92.2.206. PMID 11396580.

- ^ Galbraith, David (June 1995). "DNA Fingerprinting of Turtles". Journal of Herpetology. 29 (2): 285–291. doi:10.2307/1564569. JSTOR 1564569.

- ^ Bowen & Gillingham 2004, p. 17

- ^ a b NHESP 2007, p. 3

- ^ Bowen & Gillingham 2004, p. 19

- ^ "Vulnerable Wood Turtle (Glyptemys inscuplta) Special Management Practices" (PDF). Government of Nova Scotia. 2017.

- ^ "Wood Turtle Monitoring and Stewardship". Clean Annapolis River Project. 2017.

- Bibliography

- Bowen, Kenneth; Gillingham, James C. (2004). "R9 Species Conservation Assessment for Wood Turtle – Glyptemys insculpta (LeConte, 1830)" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- Ernst, Carl; Lovich, Jeffrey (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 250–262. ISBN 978-0-8018-9121-2.

- "Wood Turtle Fact Sheet". Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife. 2007. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- "Assessment and Update Status Report on the Wood Turtle Glyptemys insculpta in Canada" (PDF). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2007. pp. iv-42. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

External links

[edit]- Glyptemys insculpta, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- Wood Turtle, State of Connecticut, Department of Energy and Environmental Protection

- Wood Turtle, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

- Wood Turtle, Michigan Department of Natural Resources

- Wood Turtle, Reptiles and Amphibians of Iowa

- IUCN Red List endangered species

- Glyptemys

- Turtles of North America

- Reptiles of the United States

- Fauna of the Eastern United States

- Fauna of the Great Lakes region (North America)

- Reptiles of Ontario

- Endangered fauna of the United States

- Endangered fauna of North America

- Reptiles described in 1830

- Taxa named by John Eatton Le Conte