Chariots of Fire

| Chariots of Fire | |

|---|---|

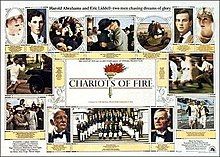

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Hugh Hudson |

| Written by | Colin Welland |

| Produced by | David Puttnam |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | David Watkin |

| Edited by | Terry Rawlings |

| Music by | Vangelis |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox (International) The Ladd Company Warner Bros. (United States and Canada) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.5 million (£3 million)[2] or £4,032,859[3] |

| Box office | $59 million (U.S. and Canada)[4] |

Chariots of Fire is a 1981 historical sports drama film directed by Hugh Hudson, written by Colin Welland and produced by David Puttnam. It is based on the true story of two British athletes in the 1924 Olympics: Eric Liddell, a devout Scottish Christian who runs for the glory of God, and Harold Abrahams, an English Jew who runs to overcome prejudice. Ben Cross and Ian Charleson star as Abrahams and Liddell, alongside Nigel Havers, Ian Holm, John Gielgud, Lindsay Anderson, Cheryl Campbell, Alice Krige, Brad Davis and Dennis Christopher in supporting roles. Kenneth Branagh and Stephen Fry make their debuts in minor roles.

Chariots of Fire was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Original Score for Vangelis's electronic theme tune. At the 35th British Academy Film Awards, the film was nominated in 11 categories and won in three, including Best Film. It is ranked 19th in the British Film Institute's list of Top 100 British films.

The film's title was inspired by the line "Bring me my Chariot of fire!" from the William Blake poem adapted into the British hymn and unofficial English anthem "Jerusalem"; the hymn is heard at the end of the film.[5] The original phrase "chariot(s) of fire" is from 2 Kings 2:11 and 6:17 in the Bible.

Plot

[edit]During a 1978 funeral service in London in honour of the life of Harold Abrahams, headed by his former colleague Lord Andrew Lindsay, there is a flashback to when he was young and in a group of athletes running along a beach.

In 1919, Harold Abrahams enters the University of Cambridge, where he experiences antisemitism from the staff but enjoys participating in the Gilbert and Sullivan club. He becomes the first person to complete the Trinity Great Court Run, running around the college courtyard in the time it takes for the clock to strike 12, and achieves an undefeated string of victories in various national running competitions. Although focused on his running, he falls in love with Sybil Gordon, a leading Gilbert and Sullivan soprano.[a]

Eric Liddell, born in China to Scottish missionary parents, is in Scotland. His devout sister Jennie disapproves of Liddell's plans to pursue competitive running. Still, Liddell sees running as a way of glorifying God before returning to China to work as a missionary. When they first race against each other, Liddell beats Abrahams. Abrahams takes it poorly, but Sam Mussabini, a professional trainer he had approached earlier, offers to take him on to improve his technique. This attracts criticism from the Cambridge college masters, who assert that it isn't gentlemanly for an amateur to "play the tradesman" by employing a professional coach. Abrahams dismisses this concern, interpreting it as cover for antisemitic and class-based prejudice. When Liddell accidentally misses a church prayer meeting because of his running, Jennie upbraids him and accuses him of no longer caring about God. Eric tells her that though he intends to return eventually to the China mission, he feels divinely inspired when running and that not to run would be to dishonour God.

After years training and racing, the two athletes are accepted to represent Great Britain in the 1924 Olympics in Paris. Also accepted are Abrahams's Cambridge friends, Andrew Lindsay, Aubrey Montague, and Henry Stallard. While boarding the boat to France for the Olympics, Liddell discovers the heats for his 100-metre race will be on a Sunday. Despite intense pressure from the Prince of Wales and the British Olympic Committee, he refuses to run the race because his Christian convictions prevent him from running on the Lord's Day. A solution is found thanks to Liddell's teammate Lindsay, who, having already won a silver medal in the 400 metres hurdles, offers to give his place in the 400-metre race on the following Thursday to Liddell, who gratefully accepts. Liddell's religious convictions in the face of national athletic pride make headlines around the world; he delivers a sermon at the Paris Church of Scotland that Sunday, and quotes from Isaiah 40.

Abrahams is badly beaten by the heavily favoured United States runners in the 200-metre race. He knows his last chance for a medal will be the 100 metres. He competes in the race and wins. His coach Mussabini, who was barred from the stadium, is overcome that the years' dedication and training have paid off with an Olympic gold medal. Now Abrahams can get on with his life and reunite with his girlfriend Sybil, whom he has neglected for the sake of running. Before Liddell's race, the American coach remarks dismissively to his runners that Liddell has little chance of doing well in his new, far longer, 400-metre race. But one of the American runners, Jackson Scholz, hands Liddell a note of support that quotes 1 Samuel 2:30. Liddell defeats the American favourites and wins the gold medal. The British team returns home triumphant.

A textual epilogue reveals that Abrahams married Sybil and became the elder statesman of British athletics while Liddell went on to do missionary work and was mourned by all of Scotland following his death in Japanese-occupied China.

Cast

[edit]- Ben Cross as Harold Abrahams, a Jewish student at Cambridge University

- Ian Charleson as Eric Liddell, the son of Scottish missionaries to China

- Nigel Havers as Lord Andrew Lindsay, a Cambridge student runner (partially based on David Burghley and Douglas Lowe)

- Nicholas Farrell as Aubrey Montague, a runner and friend of Harold Abrahams

- Ian Holm as Sam Mussabini, Abrahams' running coach

- John Gielgud as Master of Trinity College at Cambridge University

- Lindsay Anderson as Master of Caius College at Cambridge University

- Cheryl Campbell as Jennie Liddell, Eric's devout sister

- Alice Krige as Sybil Gordon, a D'Oyly Carte soprano and Abrahams's fiancée (his actual fiancée was Sybil Evers)

- Struan Rodger as Sandy McGrath, Liddell's friend and running coach

- Nigel Davenport as Lord Birkenhead, member of the British Olympic Committee, who counsels the athletes

- Patrick Magee as Lord Cadogan, chairman of the British Olympics Committee, who is unsympathetic to Liddell's religious plight

- David Yelland as the Prince of Wales, who tries to get Liddell to change his mind about running on Sunday

- Peter Egan as the Duke of Sutherland, president of the British Olympic Committee, who is sympathetic to Liddell

- Daniel Gerroll as Henry Stallard, a Cambridge student and runner

- Brad Davis as Jackson Scholz, American Olympic runner

- Dennis Christopher as Charley Paddock, American Olympic runner

- Richard Griffiths as Mr Rogers, Head Porter at Caius College

Other actors in smaller roles include John Young as Eric and Jennie's father Reverend J.D. Liddell, Yvonne Gilan as their mother Mary, Benny Young as their older brother Rob, Yves Beneyton as French runner Géo André, Philip O'Brien as American coach George Collins, Patrick Doyle as Jimmie,[6] and Ruby Wax as Bunty.[7] Kenneth Branagh, who worked as a set gofer, appears as an extra in the Cambridge Society Day sequence.[8] Stephen Fry has a likewise uncredited role as a Gilbert-and-Sullivan Club singer.[8]

Production

[edit]Screenplay

[edit]

Producer David Puttnam was looking for a story in the mould of A Man for All Seasons (1966), regarding someone who follows his conscience, and felt that sport provided clear situations in this sense.[9] He discovered Eric Liddell's story by accident in 1977, when he happened upon An Approved History of the Olympic Games, a reference book on the Olympics, while housebound from the flu, in a rented house in Malibu.[10][11][12][13]

Screenwriter Colin Welland, commissioned by Puttnam, did an enormous amount of research for his Academy Award-winning script. Among other things, he took out advertisements in London newspapers seeking memories of the 1924 Olympics, went to the National Film Archives for pictures and footage of the 1924 Olympics, and interviewed everyone involved who was still alive. Welland just missed Abrahams, who died on 14 January 1978, but he did attend Abrahams' February 1978 memorial service, which inspired the present-day framing device of the film.[14] Aubrey Montague's son saw Welland's newspaper ad and sent him copies of the letters his father had sent home – which gave Welland something to use as a narrative bridge in the film. Except for changes in the greetings of the letters from "Darling Mummy" to "Dear Mum" and the change from Oxford to Cambridge, all of the readings from Montague's letters are from the originals.[15]

Welland's original script also featured, in addition to Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams, a third protagonist, 1924 Olympic gold medallist Douglas Lowe, who was presented as a privileged aristocratic athlete. However, Lowe refused to have anything to do with the film, and his character was written out and replaced by the fictional character of Lord Andrew Lindsay.[16]

Initial financing towards development costs was provided by Goldcrest Films, who then sold the project to Mohamed Al-Fayed's Allied Stars, but kept a percentage of the profits.[17]

Ian Charleson wrote Eric Liddell's speech to the post-race workingmen's crowd at the Scotland v. Ireland races. Charleson, who had studied the Bible intensively in preparation for the role, told director Hugh Hudson that he didn't feel the portentous and sanctimonious scripted speech was either authentic or inspiring. Hudson and Welland allowed him to write words he personally found inspirational instead.[18]

Puttnam chose Hugh Hudson, a multiple award-winning advertising and documentary filmmaker who had never helmed a feature film, to direct Chariots of Fire. Hudson and Puttnam had known each other since the 1960s when Puttnam was an advertising executive and Hudson was making films for ad agencies. In 1977, Hudson had also been second-unit director on the Puttnam-produced film Midnight Express.[19]

Casting

[edit]Director Hugh Hudson was determined to cast young, unknown actors in all the major roles of the film, and to back them up by using veterans like John Gielgud, Lindsay Anderson, and Ian Holm as their supporting cast. Hudson and producer David Puttnam did months of fruitless searching for the perfect actor to play Eric Liddell. They then saw Scottish stage actor Ian Charleson performing the role of Pierre in the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of Piaf, and knew immediately they had found their man. Unbeknownst to them, Charleson had heard about the film from his father, and desperately wanted to play the part, feeling it would "fit like a kid glove".[20]

Ben Cross, who plays Harold Abrahams, was discovered while playing Billy Flynn in Chicago. In addition to having a natural pugnaciousness, he had the desired ability to sing and play the piano.[15][21] Cross was thrilled to be cast, and said he was moved to tears by the film's script.[22]

20th Century-Fox, which put up half of the production budget in exchange for distribution rights outside of North America,[23] insisted on having a couple of notable American names in the cast.[13] Thus the small parts of the two American champion runners, Jackson Scholz and Charley Paddock, were cast with recent headliners: Brad Davis had recently starred in Midnight Express (also produced by Puttnam), and Dennis Christopher had recently starred, as a young bicycle racer, in the popular indie film Breaking Away.[22]

All of the actors portraying runners underwent an intensive three-month training regimen with renowned running coach Tom McNab. This training and isolation of the actors also created a strong bond and sense of camaraderie among them.[22]

Filming

[edit]

The beach scenes showing the athletes running towards the Carlton Hotel at Broadstairs, Kent,[24] were shot in Scotland on West Sands, St Andrews next to the 18th hole of the Old Course at St Andrews Links. A plaque now commemorates the filming.[25][26] The impact of these scenes (as the athletes run in slow motion to Vangelis's music) prompted Broadstairs town council to commemorate them with a seafront plaque.[27]

All of the indoor Cambridge scenes were actually filmed at Hugh Hudson's alma mater Eton College, because Cambridge refused filming rights, fearing depictions of anti-Semitism. The Cambridge administration greatly regretted the decision after the film's enormous success.[15]

Liverpool Town Hall was the setting for the scenes depicting the British Embassy in Paris.[15] The Colombes Olympic Stadium in Paris was represented by the Oval Sports Centre, Bebington, Merseyside.[28] The nearby Woodside ferry terminal was used to represent the embarkation scenes set in Dover.[28] The railway station scenes were filmed in York, using locomotives from the National Railway Museum.[15] The filming of the Scotland–France international athletic meeting took place at Goldenacre Sports Ground in Edinburgh, owned by George Heriot's School, while the Scotland–Ireland meeting was at the nearby Inverleith Sports Ground.[29][30] The scene depicting a performance of The Mikado was filmed in the Royal Court Theatre, Liverpool, with members of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company who were on tour.[31]

Editing

[edit]The film was slightly altered for the U.S. audience. A brief scene depicting a pre-Olympics cricket game between Abrahams, Liddell, Montague, and the rest of the British track team appears shortly after the beginning of the original film. For the American audience, this brief scene was deleted. In the U.S., to avoid the initial G rating, which had been strongly associated with children's films and might have hindered box office sales, a different scene was used – one depicting Abrahams and Montague arriving at a Cambridge railway station and encountering two First World War veterans who use an obscenity – in order to be given a PG rating.[32] An off-camera retort of, "Win it for Israel" among exhortations of fellow students of Abrahams before he takes on the challenge of The Great Court Run was absent from the final cuts theatrically distributed in the U.S. However, they can be heard in versions broadcast on such cable outlets as TCM.

Soundtrack

[edit]

Although the film is a period piece set in the 1920s, the Academy Award-winning original soundtrack composed by Vangelis (credited as Vangelis Papathanassiou) uses a contemporary 1980s electronic sound, with a strong use of synthesizer and piano among other instruments. This was a departure from earlier period films, which employed sweeping orchestral instrumentals. The title theme of the film has been used in subsequent films and television shows during slow-motion segments.

Vangelis, a Greek-born electronic composer who moved to Paris in the late 1960s, had been living in London since 1974.[33] Director Hugh Hudson had collaborated with him on documentaries and commercials, and was also particularly impressed with his 1979 albums Opera Sauvage and China.[34] David Puttnam also greatly admired Vangelis's body of work, having originally selected his compositions for his previous film Midnight Express.[35] Hudson made the choice for Vangelis and for a modern score: "I knew we needed a piece which was anachronistic to the period to give it a feel of modernity. It was a risky idea but we went with it rather than have a period symphonic score."[19] The soundtrack had a personal significance to Vangelis: after composing the theme he told Puttnam, "My father is a runner, and this is an anthem to him."[14][33]

Hudson originally wanted Vangelis's 1977 tune "L'Enfant",[36] from his Opera Sauvage album, to be the title theme of the film, and the beach running sequence was actually filmed with "L'Enfant" playing on loudspeakers for the runners to pace to. Vangelis finally convinced Hudson he could create a new and better piece for the film's main theme – and when he played the "Chariots of Fire" theme for Hudson, it was agreed the new tune was unquestionably better.[37] The "L'Enfant" melody still made it into the film: when the athletes reach Paris and enter the stadium, a brass band marches through the field, and first plays a modified, acoustic performance of the piece.[38] Vangelis's electronic "L'Enfant" track eventually was used prominently in the 1982 film The Year of Living Dangerously.

Some pieces of Vangelis's music in the film did not end up on the film's soundtrack album. One of them is the background music to the race Eric Liddell runs in the Scottish highlands. This piece is a version of "Hymne", the original version of which appears on Vangelis's 1979 album, Opéra sauvage. Various versions are also included on Vangelis's compilation albums Themes, Portraits, and Odyssey: The Definitive Collection, though none of these include the version used in the film.

Five lively Gilbert and Sullivan tunes also appear in the soundtrack, and serve as jaunty period music which counterpoints Vangelis's modern electronic score. These are: "He is an Englishman" from H.M.S. Pinafore, "Three Little Maids From School Are We" from The Mikado, "With Catlike Tread" from The Pirates of Penzance, "The Soldiers of Our Queen" from Patience, and "There Lived a King" from The Gondoliers.

The film also incorporates a major traditional work: "Jerusalem", sung by a British choir at the 1978 funeral of Harold Abrahams. The words, written by William Blake in 1804–08, were set to music by Hubert Parry in 1916 as a celebration of England. This hymn has been described as "England's unofficial national anthem",[39] concludes the film and inspired its title.[40] A handful of other traditional anthems and hymns and period-appropriate instrumental ballroom-dance music round out the film's soundtrack.

Release

[edit]The film was distributed by 20th Century-Fox and selected for the 1981 Royal Film Performance with its premiere on 30 March 1981 at the Odeon Haymarket before opening to the public the following day. It opened in Edinburgh on 4 April and in Oxford and Cambridge on 5 April[41] with other openings in Manchester and Liverpool before expanding further in May into 20 additional London cinemas and 11 others nationally. It was shown in competition at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival on 20 May.[42]

The film was distributed by The Ladd Company through Warner Bros. in North America and released on 25 September 1981 in Los Angeles, California and in the New York Film Festival, on 26 September 1981 in New York and on 9 April 1982 in the United States.[43]

Reception

[edit]Since its release, Chariots of Fire has received generally positive reviews from critics. As of 2024[update], the film holds an 84% rating from the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 117 reviews, with a weighted average of 7.8/10. The site's consensus reads: "Decidedly slower and less limber than the Olympic runners at the center of its story, Chariots of Fire nevertheless manages to make effectively stirring use of its spiritual and patriotic themes."[44] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 78 out of 100 based on 19 critics' reviews.[45]

For its 2012 re-release, Kate Muir of The Times gave the film five stars, writing: "In a time when drug tests and synthetic fibres have replaced gumption and moral fibre, the tale of two runners competing against each other in the 1924 Olympics has a simple, undiminished power. From the opening scene of pale young men racing barefoot along the beach, full of hope and elation, backed by Vangelis's now famous anthem, the film is utterly compelling."[46]

In its first four weeks at the Odeon Haymarket it grossed £106,484.[47] The film was the highest-grossing British film for the year with theatrical rentals of £1,859,480.[48] Its gross of almost $59 million in the United States and Canada made it the highest-grossing film import into the US (i.e. a film without any US input) at the time, surpassing Meatballs' $43 million.[4][49]

The film was included by the Vatican in a list of important films compiled in 1995, under the category of "Values".[50]

Accolades

[edit]The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning four (including Best Picture). When accepting his Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, Colin Welland famously announced "The British are coming".[51] It was the first film released by Warner Bros. to win Best Picture since My Fair Lady in 1964.

American Film Institute recognition

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers - No. 100

Other honours

- BFI Top 100 British films (1999) – rank 19

- Hot 100 No. 1 Hits of 1982 (USA) (8 May) – Vangelis, Chariots of Fire theme

Historical accuracy

[edit]Chariots of Fire is a film about achieving victory through self sacrifice and moral courage. While the producers' intent was to make a cinematic work that was historically authentic, the film was not intended to be historically accurate. Numerous liberties were taken with the actual historical chronology, the inclusion and exclusion of notable people, and the creation of fictional scenes for dramatic purpose, plot pacing and exposition.[53][54][55][56][57]

Characters

[edit]The film depicts Abrahams as attending Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, with three other Olympic athletes: Henry Stallard, Aubrey Montague, and Lord Andrew Lindsay. However, whereas Abrahams and Stallard were indeed students there, Montague attended Oxford and not Cambridge.[58] Aubrey Montague sent daily letters to his mother about his time at Oxford and the Olympics; these letters were the basis of Montague's narration in the film.

The character of Lindsay was based partially on David Cecil (Lord Burghley), a significant figure in the history of British athletics. Although Burghley did attend Cambridge, he was not a contemporary of Harold Abrahams, as Abrahams was an undergraduate from 1919 to 1923 and Burghley was at Cambridge from 1923 to 1927. One scene in the film depicts the Burghley-based "Lindsay" as practising hurdles on his estate with full champagne glasses placed on each hurdle – this was something the wealthy Burghley did, although he used matchboxes instead of champagne glasses.[14] Burghley was not willing to be involved in the film and the fictional character of Lindsay was created when Douglas Lowe, who was Britain's third athletics gold medallist in the 1924 Olympics, also declined.[59]

Another scene in the film recreates the Great Court Run, in which the runners attempt to run around the perimeter of the Great Court at Trinity College, Cambridge in the time it takes the clock to strike 12 at midday. The film shows Abrahams performing the feat for the first time in history. In fact, Abrahams never attempted this race, and at the time of filming the only person on record known to have succeeded was Lord Burghley, in 1927. In Chariots of Fire, Lindsay, who is based on Lord Burghley, runs the Great Court Run with Abrahams in order to spur him on, and crosses the finish line just a moment too late. Since the film's release, the Great Court Run has also been successfully run by Trinity undergraduate Sam Dobin, in October 2007.[60]

In the film, Eric Liddell is tripped up by a Frenchman in the 400-metre event of a Scotland–France international athletic meeting. He recovers, makes up a 20-metre deficit, and wins. This was based on fact; the actual race was the 440 yards at a Triangular Contest meet between Scotland, England, and Ireland at Stoke-on-Trent in England in July 1923. His achievement was remarkable as he had already won the 100- and 220-yard events that day.[61] Also unmentioned with regard to Liddell is that it was he who introduced Abrahams to Sam Mussabini.[62] This is alluded to: in the film, Abrahams first encounters Mussabini while he is watching Liddell race.

Abrahams and Liddell did race against each other twice, but not as depicted in the film, which shows Liddell winning the final of the 100 yards against a shattered Abrahams at the 1923 AAA Championship at Stamford Bridge. In fact, they raced only in a heat of the 220 yards, which Liddell won, five yards ahead of Abrahams, who did not progress to the final. In the 100 yards, Abrahams was eliminated in the heats and did not race against Liddell, who won the finals of both races the next day. They also raced against each other in the 200 m final at the 1924 Olympics, and this was also not shown in the film.[63]

Abrahams' fiancée is misidentified as Sybil Gordon, a soprano with the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. In fact, in 1936, Abrahams married Sybil Evers, who also performed with D'Oyly Carte, but they did not meet until 1934.[64] Also, in the film, Sybil is depicted as singing the role of Yum-Yum in The Mikado, but neither Gordon nor Evers ever sang that role with D'Oyly Carte,[65][66] although Evers was known for her charm in singing Peep-Bo, one of the two other "little maids from school".[64] Harold Abrahams' love of and heavy involvement with Gilbert and Sullivan, as depicted in the film, is factual.[15]

Liddell's sister was several years younger than she was portrayed in the film. Her disapproval of Liddell's track career was creative licence; she actually fully supported his sporting work. Jenny Liddell Somerville cooperated fully with the making of the film and has a brief cameo in the Paris Church of Scotland during Liddell's sermon.[67]

At the memorial service for Harold Abrahams, which opens the film, Lord Lindsay mentions that he and Aubrey Montague are the only members of the 1924 Olympic team still alive. However, Montague died in 1948, 30 years before Abrahams' death.

Paris Olympics 1924

[edit]In the film, the 100m bronze medallist is a character called "Tom Watson"; the real medallist was Arthur Porritt of New Zealand, who refused permission for his name to be used in the film, allegedly out of modesty, and his wish was accepted by the film's producers, even though his permission was not necessary.[68] However, the brief back-story given for Watson, who is called up to the New Zealand team from the University of Oxford, substantially matches Porritt's history. With the exception of Porritt, all the runners in the 100m final are identified correctly when they line up for inspection by the Prince of Wales.

Jackson Scholz is depicted as handing Liddell an inspirational Bible-quotation message before the 400 metres final: "It says in the Old Book, 'He that honors me, I will honor.' Good luck."[69] In reality, the note was from members of the British team, and was handed to Liddell before the race by his attending masseur at the team's Paris hotel.[70] For dramatic purposes, screenwriter Welland asked Scholz if he could be depicted handing the note, and Scholz readily agreed, saying "Yes, great, as long as it makes me look good."[15][71]

The events surrounding Liddell's refusal to race on a Sunday were changed for dramatic purposes. In the film, he does not learn that the 100-metre heat is to be held on the Christian Sabbath until he is boarding the boat to Paris. In fact, the schedule was made public several months in advance; Liddell did, however, face immense pressure to run on that Sunday and to compete in the 100 metres, and was called before a grilling by the British Olympic Committee, the Prince of Wales, and other grandees;[15] his refusal to run made headlines around the world.[72]

The decision to change races was, even so, made well before embarking to Paris, and Liddell spent the intervening months training for the 400 metres, an event in which his times were modest by international standards. Liddell's success in the Olympic 400m was thus largely unexpected.

The film depicts Lindsay, having already won a medal in the 400-metre hurdles, giving up his place in the 400-metre race for Liddell. In fact, Burghley, on whom Lindsay is loosely based, was eliminated in the heats of the 110 hurdles (he went on to win a gold medal in the 400-metre hurdles at the 1928 Olympics), and was not entered for the 400 metres.

The film reverses the order of Abrahams' 100m and 200m races at the Olympics. In reality, after winning the 100 metres race, Abrahams ran the 200 metres but finished last, Jackson Scholz taking the gold medal. In the film, before his triumph in the 100m, Abrahams is shown losing the 200m and being scolded by Mussabini. During the following scene in which Abrahams speaks with his friend Montague while receiving a massage from Mussabini, a French newspaper clipping shows Scholz and Charley Paddock with a headline stating that the 200 metres was a triumph for the United States. In the same conversation, Abrahams laments getting "beaten out of sight" in the 200. The film thus has Abrahams overcoming the disappointment of losing the 200 by going on to win the 100, a reversal of the real order.

Eric Liddell actually also ran in the 200m race, and finished third, behind Paddock and Scholz. This was the only time in reality that Liddell and Abrahams competed in the same finals race. While their meeting in the 1923 AAA Championship in the film was fictitious, Liddell's record win in that race did spur Abrahams to train even harder.[73]

Abrahams also won a silver medal as an opening runner for the 4 x 100 metres relay team, not shown in the film, and Aubrey Montague placed sixth in the steeplechase, as depicted.[58]

London Olympics' 2012 revival

[edit]Chariots of Fire became a recurring theme in promotions for the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. The film's theme was featured at the opening of the 2012 London New Year's fireworks celebrating the Olympics.[74] The runners who first tested the new Olympic Park were spurred on by the Chariots of Fire theme,[75] and the music was also used as a fanfare for the carriers of the Olympic flame on parts of its route through the UK.[76][77] The beach-running sequence was also recreated at St. Andrews and filmed as part of the Olympic torch relay.[78]

The film's theme was also performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Simon Rattle, during the Opening Ceremony of the games; the performance was accompanied by a comedy skit by Rowan Atkinson (as Mr. Bean) which included the opening beach-running footage from the film.[79] The film's theme was again played during each medal ceremony of the 2012 Olympics.

As an official part of the London 2012 Festival celebrations, a new digitally re-mastered version of the film screened in 150 cinemas throughout the UK. The re-release began 13 July 2012, two weeks before the opening ceremony of the London Olympics.[80]

A Blu-ray of the film was released on 10 July 2012 in North America,[81] and was released 16 July 2012 in the UK.[82] The release includes nearly an hour of special features, a CD sampler, and a 32-page "digibook".[83][84]

Stage adaptation

[edit]

A stage adaptation of Chariots of Fire was mounted in honour of the 2012 Olympics. The play, Chariots of Fire, which was adapted by playwright Mike Bartlett and included the Vangelis score, ran from 9 May to 16 June 2012 at London's Hampstead Theatre, and transferred to the Gielgud Theatre in the West End on 23 June, where it ran until 5 January 2013.[85] It starred Jack Lowden as Eric Liddell and James McArdle as Harold Abrahams, and Edward Hall directed. Stage designer Miriam Buether transformed each theatre into an Olympic stadium, and composer Jason Carr wrote additional music.[86][87][88] Vangelis also created several new pieces of music for the production.[89][90]

The stage version for the London Olympic year was the idea of the film's director, Hugh Hudson, who co-produced the play; he stated, "Issues of faith, of refusal to compromise, standing up for one's beliefs, achieving something for the sake of it, with passion, and not just for fame or financial gain, are even more vital today."[91]

Another play, Running for Glory, written by Philip Dart, based on the 1924 Olympics, and focusing on Abrahams and Liddell, toured parts of Britain from 25 February to 1 April 2012. It starred Nicholas Jacobs as Harold Abrahams, and Tom Micklem as Eric Liddell.[92][93]

See also

[edit]- List of films about the sport of athletics

- Chariots of Fire, a race, inspired by the film, held in Cambridge since 1991

- Great Britain at the 1924 Summer Olympics

- Sabbath breaking

References

[edit]- Chapman, James (2005). "The British Are Coming: Chariots of Fire (1981)". Past and Present: National Identity and the British Historical Film. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. pp. 270–298.

- McLaughlin, John (February 2012). "In Chariots They Ran". Runner's World. Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014.

- Ryan, Mark (2012). Running with Fire: The True Story of Chariots of Fire Hero Harold Abrahams (paperback). Robson Press.

(Original hardback: JR Books Ltd, 2011.)

Notes

[edit]- ^ AFI; Catalog American Film Institute. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- ^ Alexander Walker, Icons in the Fire: The Rise and Fall of Practically Everyone in the British Film Industry 1984-2000, Orion Books, 2005 p28

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 314.

- ^ a b Chariots of Fire at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Dans, Peter E. Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners. Rowman & Littlefield, 2009. p. 223.

- ^ "SCORE – The Podcast – Patrick Doyle". SoundTrackFest. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Ruby Wax". Metro. 27 October 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Forty years since Chariots of Fire, the quintessential Olympic film". www.insidethegames.biz. 21 April 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Goodell, Gregory. Independent Feature Film Production: A Complete Guide from Concept Through Distribution. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1982. p. xvii.

- ^ "REEL BRITANNIA". Abacus Media Rights. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Reel Britannia". BritBox. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Nichols, Peter M. The New York Times Essential Library, Children's Movies: A Critic's Guide to the Best Films Available on Video and DVD. New York: Times Books, 2003. p. 59.

- ^ a b Hugh Hudson in Chariots of Fire – The Reunion (2005 video; featurette on 2005 Chariots of Fire DVD)

- ^ a b c McLaughlin, John. "In Chariots They Ran". Runner's World. February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hugh Hudson's commentary to the 2005 Chariots of Fire DVD

- ^ Chapman 2005, pp. 274–295.

- ^ Eberts, Jake; Illott, Terry (1990). My indecision is final. Faber and Faber. p. 34.

- ^ Ian McKellen, Hugh Hudson, Alan Bates, et al. For Ian Charleson: A Tribute. London: Constable and Company, 1990. pp. 37–39. ISBN 0-09-470250-0

- ^ a b Round, Simon. "Interview: Hugh Hudson". The Jewish Chronicle. 10 November 2011.

- ^ Ian McKellen, Hugh Hudson, Alan Bates, et al. For Ian Charleson: A Tribute. London: Constable and Company, 1990. pp. xix, 9, 76.

- ^ Ben Cross – Bio on Official site Archived 22 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Wings on Their Heels: The Making of Chariots of Fire. (2005 video; featurette on 2005 DVD).

- ^ Chapman 2005, pp. 273–274.

- ^ "Carlton Hotel, Victoria Parade, Broadstairs". www.dover-kent.com. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire – St Andrews Scotland: The Movie Location Guide". www.scotlandthemovie.com. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Grannie Clark's Wynd". www.graylinescotland.com. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010.

Grannie Clark's Wynd, a public right-of-way over the 1st and the 18th of the Old Course, which was where the athletes were filmed running for the final titles shot

- ^ "'Chariots of Fire' plaque unveiled in Broadstairs". www.theisleofthanetnews.com. 29 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Chariots of Fire". Where Did They Film That?. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire". Movie Locations.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire". Movie Location Hunter.

- ^ Bradley, Ian (2005). The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford University Press. p. 576. ISBN 9780198167105.

- ^ Puttnam interviewed in BBC Radio obituary of Jack Valenti.

- ^ a b "Daily Telegraph newspaper, 21 November 1982".

- ^ MacNab, Geoffrey. "Everyone Was a Winner when British Talent Met the Olympic Spirit". The Independent. 13 April 2012.

- ^ Hubbert, Julie. Celluloid Symphonies: Texts and Contexts in Film Music History. University of California Press, 2011. p. 426.

- ^ ""L'Enfant", from Opera Sauvage". YouTube.

- ^ Vangelis in Chariots of Fire – The Reunion (2005 video; featurette on 2005 Chariots of Fire DVD)

- ^ "Trivia about Vangelis".

- ^ Sanderson, Blair. Hubert Parry. AllMusic Guide, reprinted in Answers.com.

- ^ Manchel, Frank. Film Study: An Analytical Bibliography. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1990. p. 1013

- ^ "Chariots of Fire (advertisement)". The Times. 31 March 1981. p. 11.

- ^ "Putnam's Careful Engineering Of Public Response In Homeland". Variety. 13 May 1981. p. 241.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (6 February 1982). "Sometimes a Movie Makes a Studio Proud". The New York Times. p. 11. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ [1]. "First Night Reviews: Chariots of Fire". Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ "Premiere Engagement at the Odeon Haymarket (advertisement)". Variety. 13 May 1981. pp. 242–243.

- ^ "Top Grossing British Films on the U.K. Market: '81-'82". Variety. 12 January 1983. p. 146.

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (7 July 1982). "'Chariots of Fire' Becomes Top Import Pic In U.S. B.O. History". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "Vatican Best Films List". Official website of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "This week's new theatre and dance". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2012

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Chariots of Fire". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire: history gets the runaround". The Guardian. 19 July 2012.

- ^ "Sporting Icons: Past and Present". Sport in History. 33 (4): 445–464. 2013. doi:10.1080/17460263.2013.850270. S2CID 159478372.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire". History Today. 62 (8). August 2012.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire". The Outlook. 1982.

- ^ "In Chariots They Ran". Runners World. 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b Aubrey Montague biography at SportsReference.com

- ^ Chapman 2005, pp. 275, 295.

- ^ "Student runs away with "Chariots of Fire" record". Reuters. 27 October 2007. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Ramsey, Russell W. (1987). God's Joyful Runner. Bridge Publishing, Inc. p. 54. ISBN 0-88270-624-1.

- ^ "A Sporting Nation: Eric Liddell". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ McCasland, David (2001). Pure Gold: A New Biography of the Olympic Champion Who Inspired Chariots of Fire. Discovery House. ISBN 1572931302.

- ^ a b Ryan 2012, p. 188.

- ^ Stone, David. Sybil Gordon at the Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company website, 23 September 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2022

- ^ Stone, David. Sybil Evers at the Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company website, 28 January 2002. Retrieved 25 October 2022

- ^ Ramsey, Russell W. A Lady – A Peacemaker. Boston: Branden Publishing Company, 1988.

- ^ Arthur Espie Porritt 1900–1994. "Reference to Porritt's modesty". Library.otago.ac.nz. Archived from the original on 30 October 2005. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The quoted passage is First Samuel 2:30.

- ^ Reid, Alasdair. "Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell". The Times. 1 August 2000.

- ^ "Britain's 1924 Olympic Champs Live Again in 'Chariots of Fire'—and Run Away with the Oscars". People. 17 (18). 10 May 1982. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Murray, Feg. "DID YOU KNOW THAT ...". Los Angeles Times. 24 June 1924. Full headline reads, "Did You Know That Famous Scotch Sprinter Will Not Run in the Olympic 100 Metres Because The Trials Are Run on Sunday".

- ^ "Recollections by Sir Arthur Marshall". Content.ericliddell.org. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ^ "London Fireworks 2012 - New Year Live - BBC One". YouTube. January 2012.

- ^ "London 2012: Olympic Park Runners Finish Race". BBC News. 31 March 2012.

- ^ "Musicians Set to Fanfare the Flame" Archived 28 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph. 3 April 2012.

- ^ Line the Streets: Celebration Guide Archived 24 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. London 2012. p. 4.

- ^ "News: Torch Relay". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Mr. Bean's 'Chariots of Fire' Skit at 2012 London Olympics Opening Ceremony". International Business Times. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire Returns to UK Cinemas Ahead of the Olympics" Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. British Film Institute. 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire – Blu-ray". Amazon.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire – 30th Anniversary Limited Edition Blu-ray". Amazon UK.

- ^ Sluss, Justin. "1981 Hugh Hudson Directed Film Chariots of Fire Comes to Blu-ray in July" Archived 21 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. HighDefDiscNews.com.

- ^ "Chariots of Fire Blu-ray press release". Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Rees, Jasper. "Chariots of Fire Is Coming!" The Arts Desk. 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Cast Announced for Hampstead Theatre's Chariots of Fire; Opens May 9". Broadway World. 2 April 2012.

- ^ Girvan, Andrew. "Black Watch's Lowden plays Eric Liddell in Chariots of Fire" Archived 11 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. What's on Stage. 9 March 2012.

- ^ Chariots of Fire – Hampstead Theatre Archived 6 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Twitter: Chariots Tweeter, 16 April 2012, 18 April 2012.

- ^ Rees, Jasper. "Chariots of Fire: The British Are Coming... Again". The Daily Telegraph. 3 May 2012.

- ^ Jury, Louise. "Theatre to Run Chariots of Fire with Vangelis Tracks". London Evening Standard. 30 January 2012.

- ^ Elkin, Susan. "Running for Glory". The Stage. 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Olympic Play Is Victory on Stage" Archived 5 May 2013 at archive.today. This Is Kent. 10 February 2012.

External links

[edit]- Vangelis performing theme with film clips on YouTube "VangelisVEVO". YouTube. June 2017.

- The Real Chariots of Fire (2012) documentary on YouTube

- Chariots of Fire at IMDb

- Chariots of Fire at the TCM Movie Database

- Chariots of Fire at Rotten Tomatoes

- Critics' Picks: Chariots of Fire retrospective video by A. O. Scott, The New York Times (2008)

- Four speeches from the movie in text and audio from AmericanRhetoric.com

- Chariots of Fire Archived 22 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine review by Roger Ebert

- Chariots of Fire review in Variety

- Chariots of Fire at the Arts & Faith Top 100 Spiritually Significant Films

- Chariots of Fire Archived 14 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Filming locations

- Chariots of Fire screenplay, second draft, February 1980

- Great Court Run

- Chariots of Fire play – Hampstead Theatre

- 1981 films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s French-language films

- 20th Century Fox films

- 1980s biographical drama films

- Best Foreign Language Film Golden Globe winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- British biographical drama films

- British sports drama films

- University of Cambridge in fiction

- Films about Christianity

- Films about competitions

- Films about religion

- Films directed by Hugh Hudson

- Films set in 1919

- Films set in 1920

- Films set in 1923

- Films set in 1924

- Films set in 1978

- Films set in Cambridge

- Films set in Kent

- Films set in London

- Films set in Paris

- Films set in England

- Films set in France

- Films set in Scotland

- Films set in the University of Cambridge

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Goldcrest Films films

- Biographical films about Jewish people

- Films about the 1924 Summer Olympics

- Films about Olympic track and field

- Running films

- Sport at the University of Cambridge

- Sports films based on actual events

- Warner Bros. films

- Films scored by Vangelis

- Films that won the Best Costume Design Academy Award

- Films set on beaches

- Religion and sports

- Films shot in Edinburgh

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Films produced by David Puttnam

- The Ladd Company films

- Biographical films about sportspeople

- Cultural depictions of track and field athletes

- 1981 directorial debut films

- 1981 drama films

- Films shot in York

- Films shot in North Yorkshire

- Films shot in Yorkshire

- Films shot in Liverpool

- Films shot in Merseyside

- Films shot in Kent

- Films about antisemitism

- 1980s British films

- Toronto International Film Festival People's Choice Award winners

- Cultural depictions of Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson

- English-language biographical drama films