Cellphone surveillance

Cellphone surveillance (also known as cellphone spying) may involve tracking, bugging, monitoring, eavesdropping, and recording conversations and text messages on mobile phones.[1] It also encompasses the monitoring of people's movements, which can be tracked using mobile phone signals when phones are turned on.[2]

Mass cellphone surveillance

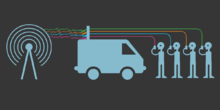

[edit]Stingray devices

[edit]StingRay devices are a technology that mimics a cellphone tower, causing nearby cellphones to connect and pass data through them instead of legitimate towers.[3] This process is invisible to the end-user and allows the device operator full access to any communicated data.[3] They are also capable of capturing information from phones of bystanders.[4] This technology is a form of man-in-the-middle attack.[5]

StingRays are used by law enforcement agencies to track people's movements, and intercept and record conversations, names, phone numbers and text messages from mobile phones.[1] Their use entails the monitoring and collection of data from all mobile phones within a target area.[1] Law enforcement agencies in Northern California that have purchased StingRay devices include the Oakland Police Department, San Francisco Police Department, Sacramento County Sheriff's Department, San Jose Police Department and Fremont Police Department.[1] The Fremont Police Department's use of a StingRay device is in a partnership with the Oakland Police Department and Alameda County District Attorney's Office.[1]

End-to-end encryption such as Signal protects traffic against StingRay devices via cryptographic strategies.[6]

Dirtbox (DRT box)

[edit]Dirtbox is a technology similar to Stingrays that are usually mounted on aerial vehicles that can mimic cell sites and also jam signals. The device uses an IMSI-catcher and is claimed to be able to bypass cryptographic encryption by getting IMSI numbers and ESNs (electronic serial numbers).

Tower dumps

[edit]A tower dump is the sharing of identifying information by a cell tower operator, which can be used to identify where a given individual was at a certain time.[7][8] As mobile phone users move, their devices will connect to nearby cell towers in order to maintain a strong signal even while the phone is not actively in use.[9][8] These towers record identifying information about cellphones connected to them which then can be used to track individuals.[7][8]

In most of the United States, police can get many kinds of cellphone data without obtaining a warrant. Law-enforcement records show police can use initial data from a tower dump to ask for another court order for more information, including addresses, billing records and logs of calls, texts and locations.[8]

Targeted surveillance

[edit]Software vulnerabilities

[edit]Cellphone bugs can be created by disabling the ringing feature on a mobile phone, allowing a caller to call a phone to access its microphone and listening. One example of this was the group FaceTime bug. This bug enables people to eavesdrop on conversations without calls being answered by the recipient.

In the United States, the FBI has used "roving bugs", which entails the activation of microphones on mobile phones to the monitoring of conversations.[10]

Cellphone spying software

[edit]Cellphone spying software[11] is a type of cellphone bugging, tracking, and monitoring software that is surreptitiously installed on mobile phones. This software can enable conversations to be heard and recorded from phones upon which it is installed.[12] Cellphone spying software can be downloaded onto cellphones.[13] Cellphone spying software enables the monitoring or stalking of a target cellphone from a remote location with some of the following techniques:[14]

- Allowing remote observation of the target cellphone position in real-time on a map

- Remotely enabling microphones to capture and forward conversations. Microphones can be activated during a call or when the phone is on standby for capturing conversations near the cellphone.

- Receiving remote alerts and/or text messages each time somebody dials a number on the cellphone

- Remotely reading text messages and call logs

Cellphone spying software can enable microphones on mobile phones when phones are not being used, and can be installed by mobile providers.[10]

Bugging

[edit]Intentionally hiding a cell phone in a location is a bugging technique. Some hidden cellphone bugs rely on Wi-Fi hotspots, rather than cellular data, where the tracker rootkit software periodically "wakes up" and signs into a public Wi-Fi hotspot to upload tracker data onto a public internet server.

Lawful interception

[edit]Governments may sometimes legally monitor mobile phone communications - a procedure known as lawful interception.[15]

In the United States, the government pays phone companies directly to record and collect cellular communications from specified individuals.[15] U.S. law enforcement agencies can also legally track the movements of people from their mobile phone signals upon obtaining a court order to do so.[2]

These invasive legal surveillance can cause a change in public behaviors directing our ways of communication away from technology based devices.

Real-time location data

[edit]In 2018, United States cellphone carriers that sell customers' real-time location data - AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Sprint- publicly stated they would cease those data sales because the FCC found the companies had been negligent in protecting the personal privacy of their customers' data. Location aggregators, bounty hunters, and others including law enforcement agencies that did not obtain search warrants used that information. FCC Chairman Ajit Pai concluded that carriers had apparently violated federal law. However, in 2019, the carriers were continuing to sell real-time location data. In late February 2020, the FCC was seeking fines on the carriers in the case.[16]

Occurrences

[edit]In 2005, the prime minister of Greece was advised that his, over 100 dignitaries', and the mayor of Athens' mobile phones were bugged.[12] Kostas Tsalikidis, a Vodafone-Panafon employee, was implicated in the matter as using his position as head of the company's network planning to assist in the bugging.[12] Tsalikidis was found hanged in his apartment the day before the leaders were notified about the bugging, which was reported as "an apparent suicide."[17][18][19][20]

Security holes within Signalling System No. 7 (SS7), called Common Channel Signalling System 7 (CCSS7) in the US and Common Channel Interoffice Signaling 7 (CCIS7) in the UK, were demonstrated at Chaos Communication Congress, Hamburg in 2014.[21][22]

During the coronavirus pandemic Israel authorized its internal security service, Shin Bet, to use its access to historic cellphone metadata[23] to engage in location tracking of COVID-19 carriers.[24]

Detection

[edit]Some indications of possible cellphone surveillance occurring may include a mobile phone waking up unexpectedly, using a lot of battery power when on idle or when not in use, hearing clicking or beeping sounds when conversations are occurring and the circuit board of the phone being warm despite the phone not being used.[30][38][47] However, sophisticated surveillance methods can be completely invisible to the user and may be able to evade detection techniques currently employed by security researchers and ecosystem providers.[48]

Prevention

[edit]Preventive measures against cellphone surveillance include not losing or allowing strangers to use a mobile phone and the utilization of an access password.[13][14] Another technique would be turning off the phone and then also removing the battery when not in use.[13][14] Jamming devices or a Faraday cage may also work, the latter obviating removal of the battery [49]

Another solution is a cellphone with a physical (electric) switch or isolated electronic switch that disconnects the microphone and the camera without bypass, meaning the switch can be operated by the user only - no software can connect it back.

See also

[edit]- Bluesnarfing

- Carpenter v. United States

- Carrier IQ

- Cellphone jammer

- Cyber stalking

- Mobile security

- Security switch

- Surveillance

- Telephone tapping

- Triggerfish (surveillance)

- Vault 7

- Virtual private network

- Voice activated recorders

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Bott, Michael; Jensen, Thom (March 6, 2014). "9 Calif. law enforcement agencies connected to cellphone spying technology". ABC News, News10. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b Richtel, Matt (December 10, 2005). "Live Tracking of Mobile Phones Prompts Court Fights on Privacy" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b Valentino-DeVries, Jennifer (2011-09-22). "'Stingray' Phone Tracker Fuels Constitutional Clash". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- ^ "New Records Detail How the FBI Pressures Police to Keep Use of Shady Phone Surveillance Technology a Secret". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ "5G Is Here—and Still Vulnerable to Stingray Surveillance". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- ^ Grauer, Yael (2017-03-08). "WikiLeaks Says the CIA Can "Bypass" Secure Messaging Apps Like Signal. What Does That Mean?". Slate. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- ^ a b Williams, Katie Bo (2017-08-24). "Verizon reports spike in government requests for cell 'tower dumps'". The Hill. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- ^ a b c d John Kelly (13 June 2014). "Cellphone data spying: It's not just the NSA". USA Today.

- ^ "Giz Explains: How Cell Towers Work". Gizmodo. 21 March 2009. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- ^ a b McCullagh, Declan; Broache, Anne (December 4, 2006). "FBI taps cell phone mic as eavesdropping tool". CNET. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Cell Phone Spying Software". Cell Phone Spying.

- ^ a b c V., Prevelakis; D., Spinellis (July 2007). "The Athens Affair". IEEE Spectrum. 44 (7): 26–33. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2007.376605. S2CID 14732055. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d Segall, Bob (June 29, 2009). "Tapping your cell phone". WTHR13 News (NBC). Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b c News report. WTHR News. (YouTube video)

- ^ a b "The price of surveillance: US gov't pays to snoop". AP News. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ "4 cellphone carriers may face $200M in fines for selling location data". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Bamford2015-09-29T02:01:02+00:00, James BamfordJames (29 September 2015). "Did a Rogue NSA Operation Cause the Death of a Greek Telecom Employee?". The Intercept. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Story of the Greek Wiretapping Scandal - Schneier on Security". www.schneier.com. 10 July 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Software engineer?s body exhumed, results in a month - Kathimerini". ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Ericsson's Greek branch fined over wire-tapping scandal". thelocal.se. 6 September 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Gibbs, Samuel (19 April 2016). "SS7 hack explained: what can you do about it?". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b Zetter, Kim. "The Critical Hole at the Heart of Our Cell Phone Networks". Wired. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Cahane, Amir (2021-01-19). "The (Missed) Israeli Snowden Moment?". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 34 (4): 694–717. doi:10.1080/08850607.2020.1838902. ISSN 0885-0607.

- ^ Cahane, Amir (2020-11-30). "Israel's SIGINT Oversight Ecosystem: COVID-19 Secret Service Location Tracking as a Test Case". University of New Hampshire Law Review. Rochester, NY. SSRN 3748401.

- ^ "Common security vulnerabilities of mobile devices - Information Age". information-age.com. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ https://www.us-cert.gov/sites/default/files/publications/cyber_threats-to_mobile_phones.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Zetter, Kim. "Hackers Can Control Your Phone Using a Tool That's Already Built Into It - WIRED". Wired. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ http://www.jsums.edu/research/files/2013/06/Cell-Phone-Vulnerabilities-1.pdf?x52307 [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Baseband vulnerability could mean undetectable, unblockable attacks on mobile phones". Boing Boing. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ [13][25][22][26][27][28][29]

- ^ Greenberg, Andy. "So Hey You Should Stop Using Texts for Two-Factor Authentication - WIRED". Wired. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "How to Protect Yourself from SS7 and Other Cellular Network Vulnerabilities". blackberry.com. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Beekman, Jethro G.; Thompson, Christopher. "Breaking Cell Phone Authentication: Vulnerabilities in AKA, IMS and Android". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.368.2999.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Security Vulnerabilities in Mobile MAC Randomization - Schneier on Security". www.schneier.com. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Newman, Lily Hay. "A Cell Network Flaw Lets Hackers Drain Bank Accounts. Here's How to Fix It". Wired. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Titcomb, James (26 August 2016). "iPhone spying flaw: What you need to know about Apple's critical security update". The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Perlroth, Nicole (25 August 2016). "IPhone Users Urged to Update Software After Security Flaws Are Found". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ [31][32][33][34][35][36][37]

- ^ Barrett, Brian. "Update Your iPhone Right Now". Wired. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Kelly, Heather (25 August 2016). "iPhone vulnerability used to target journalists, aid workers". CNNMoney. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Heisler, Yoni (8 March 2017). "Apple responds to CIA iPhone exploits uncovered in new WikiLeaks data dump". bgr.com. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Current Activity - US-CERT". www.us-cert.gov. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Ivy. "Apple: iOS 10.3.1 fixes WLAN security vulnerabilities". cubot.net. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "iOS 10.3.2 arrives with nearly two dozen security fixes". arstechnica.com. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "NVD - Home". nvd.nist.gov. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Apple users advised to update their software now, as new security patches released". welivesecurity.com. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ [39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]

- ^ Kröger, Jacob Leon; Raschke, Philip (2019). "Is My Phone Listening in? On the Feasibility and Detectability of Mobile Eavesdropping". Data and Applications Security and Privacy XXXIII. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 11559. pp. 102–120. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22479-0_6. ISBN 978-3-030-22478-3. ISSN 0302-9743.

- ^ Steven, Davis (2024-02-17). "Notifications and Alerts?". JammerX. Retrieved 2024-05-17.

https://mfggang.com/read-messages/how-to-read-texts-from-another-phone/