Cass Review

The Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People (commonly, the Cass Review) was commissioned in 2020 by NHS England and NHS Improvement[1] and led by Hilary Cass, a retired consultant paediatrician and the former president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.[2] It dealt with gender services for children and young people, including those with gender dysphoria and those identifying as transgender in England.

The final report was published on 10 April 2024,[3] and it was endorsed by both the Conservative and Labour parties. The review led to a UK ban on prescribing puberty blockers to those under 18 experiencing gender dysphoria (with the exception of existing patients or those in a clinical trial).[4] The Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust closed in March 2024 and was replaced in April with two new services, which are intended to be the first of eight regional centres.[5] In August, the pathway by which patients are referred to gender clinics was revised and a review of adult services commissioned.[6] In September, the Scottish government accepted the findings of a multidisciplinary team that NHS Scotland had set up to consider how the Cass Review's recommendations could best apply there.[7] In England a delayed clinical trial into puberty blockers is planned for early 2025.[8]

The review's recommendations have been widely welcomed by UK medical organisations.[9][10][11][12][13] However, it has been criticised by a number of medical organisations and academic groups outside of the UK and internationally for its methodology and findings.[14][15][16][17][18] Following high profile media coverage, Cass expressed concern that misinformation about the review had spread online and elsewhere,[19][20] and that her review was being weaponised against trans people.[21]

Background

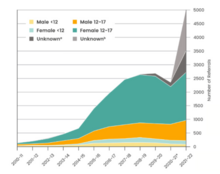

The Cass Review was commissioned by NHS England in September 2020, following a significant increase in referrals to the Gender Identity Development Service[a] and a shift in the service from a psychosocial and psychotherapeutic model to one that included hormonal treatment.[b][c] Hilary Cass, a former president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), was asked by NHS England and NHS Improvement's Quality and Innovation Committee to chair an independent review with the aim of improving gender identity services for children and young people.[29] The Cass Review's final report stated the concerns which led to its creation included very long waiting lists, of over two years per patient; an "exponential" increase in the number of children and young people requesting gender-affirming care from the NHS; a change towards earlier medical treatment in this patient cohort;[d] and concerns that there was insufficient evidence to justify the treatments being given.[e]

Methodology

The Cass Review was a non-peer-reviewed, independent narrative review which made policy recommendations for services offered to transgender and gender-expansive youth for gender dysphoria in the NHS.[f][better source needed] It commissioned a series of several peer-reviewed,[34] independent[35] systematic reviews that looked into different areas of healthcare for children and young people with distress related to gender identity,[36][37] was carried out by the University of York's Centre for Reviews and Dissemination,[g] and was published in Archives of Disease in Childhood.[39][40][41] The reviews were restricted to studies focusing on minors, excluded case studies and non-English studies, and did not provide certainty-of-evidence ratings for outcomes.[33] The reviews covered:[42][43]

- Characteristics of children and adolescents referred to specialist gender services[44]

- Impact of social transition in relation to gender for children and adolescents[45]

- Psychosocial support interventions for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence[46]

- Interventions to suppress puberty in adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence (puberty blockers)[47]

- Masculinising and feminising hormone interventions for adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence (transgender hormone therapy)[48]

- Care pathways of children and adolescents referred to specialist gender services[49]

- Clinical guidelines for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence[50][51]

The review supplemented[52][53] the evidence gathered in the systematic reviews by also comissioning qualitative and quantitative research into young people with gender dysphoria and their health outcomes,[54] conducting listening sessions and focus groups with service users and parents, holding meetings with advocacy groups, and gathering existing evidence and grey literature on the lived experiences of patients.[55]

Interim report

The interim report of the Cass Review was published in March 2022. It said the rise in referrals had led to staff being overwhelmed, and recommended the creation of a network of regional hubs to provide care and support to young people. The report said the clinical approach used by the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) "has not been subjected to some of the usual control measures" typically applied with new treatments, and raised concerns about the lack of data collection by GIDS.[56][57][58] While most children referred to GIDS did not receive endocrine treatment, there was insufficient detail provided about their broader needs when they did.[59]

The report said that while the GIDS approach to hormone interventions was initially based on the Dutch protocol, there were "significant differences" in the current NHS approach.[60] For example, the report said there were no clear guidelines for when to provide psychological support before or instead of medical treatment, endocrinologists administering puberty blockers did not attend multidisciplinary meetings, and there was insufficient capacity to increase (or even maintain) appointments once adolescents received puberty blockers.[61]

The interim report said GPs and other non-GIDS staff felt "under pressure to adopt an unquestioning affirmative approach" to children unsure of their gender. The report also said that diagnosis of gender-related distress sometimes led to "diagnostic overshadowing", where comorbidities such as poor mental health – which were usually managed by local services – were overlooked.[62] The report suggested that long wait times to access GIDS had resulted in increased distress for patients and their families, as well as less time for exploration – since patients arrived having already begun social transition and with expectations of a rapid assessment process.[63] In response, the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust said "being respectful of someone's identity does not preclude exploration", and that it agreed "support should be holistic, based on the best available evidence" without making assumptions about "the right outcome for any given young person".[64]

The interim report further said there were "gaps in the evidence" over the use of puberty blockers. A public consultation was held and a further review of evidence by NICE said there was "not enough evidence to support the safety or clinical effectiveness of puberty suppressing hormones to make the treatment routinely available at this time". Subsequently, NHS England stopped prescribing them to children.[65][66][67]

In April 2022, Health Secretary Sajid Javid told MPs that services in this area were too affirmative and narrow, and "bordering on ideological".[68] In November 2022, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) – along with regional groups ASIAPATH, EPATH, PATHA, and USPATH – issued a statement criticising the NHS England interim service specifications based on the interim report. It contested several points in the report, including the pathologising of gender diversity, the making of "outdated" assumptions regarding the nature of transgender individuals, "ignoring" newer evidence regarding such matters, and making calls for an "unconscionable degree of medical and state intrusion" into everyday matters such as pronouns and clothing choice, as well as into access to gender-affirming care. It further said that "the denial of gender-affirming treatment under the guise of 'exploratory therapy' is tantamount to 'conversion' or 'reparative' therapy under another name".[14]

Final report

The final report of the Cass Review was published on 10 April 2024. It included several systematic reviews carried out by University of York, encompassing the patient cohort, service pathways, international guidelines, social transitioning, puberty blockers, hormone treatments and psychosocial treatments.[42][69]

Findings

Lack of research

The report states that the existing evidence for both endocrine (puberty blockers and hormone therapy) and non-endocrine treatments (psychosocial interventions) in children and adolescents with gender incongruence is weak.[h]

Increase in referrals

The report found no clear explanation for the rise in the number of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria, but said there was broad agreement for attribution to a mix of biological and psychosocial factors. The report's suggested influences included a lower threshold for medical treatment, social media-related mental health consequences, abuse, access to information regarding gender dysphoria, struggles with emerging sexual orientation, and early exposure to online pornography. The report considered a rise in acceptance of transgender identities to be insufficient to explain the increase on its own.[72][44][73][74]

Social transition

A systematic review evaluated 11 studies assessing the outcomes of social transition in minors using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale and considered nine to be low quality and two to be moderate quality.[75][45] The report said that insufficient evidence was available to assess whether social transition in childhood has positive or negative effects on mental health, and that there was weak evidence for efficacy in adolescence. It also said that sex of rearing seems to influence gender identity, and suggested that early social transition may "change the trajectory" of gender identity development in children.[76]

The report said that although social transition was not usually seen as a treatment, it should be considered an "active intervention". It suggests taking "a more cautious approach" for social transition for children than for adolescents, and said pre-pubertal children undergoing social transition should be seen "as early as possible" by an experienced clinician. [77][74][78]

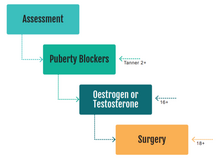

Puberty blockers

The report said the evidence base and rationale for early puberty suppression remains unclear, with unknown effects on cognitive and psychosexual development. A systematic review examined 50 studies on the use of puberty blockers using a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale and rated one as high quality, 25 as moderate quality, and 24 as low quality.[47] The review concluded that the lack of evidence means no conclusions can be made regarding the impact on gender dysphoria and mental health, but did find evidence of bone health being compromised during treatment. The review suggested puberty blockers did not provide children and young people with "time to think", since nearly all patients who went on blockers later proceeded with hormone therapy.[79][47][80] For youth assigned male at birth, the report states that blockers taken too early can make a later penile inversion vaginoplasty more difficult due to insufficient penile growth.[81] The report states one of the benefits of puberty blockers is preventing the irreversible changes of a lower voice and facial hair.[82]

Hormone therapy

The report said many unknowns remained for the use of hormone treatment among under-18s, despite longstanding use among transgender adults, with poor long-term follow-up data and outcome information on those starting younger. A systematic review evaluated 53 studies on transgender hormone therapy using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, and rated one study as high quality, 33 as moderate quality and 19 as low quality. Overall, the review found some evidence that hormone treatment improves psychological outcomes after 12 months, but found insufficient evidence regarding physical benefits and risks. The review said hormone therapy should be available from 16 years old, but that there should be a "clear clinical rationale" for the prescription of hormone therapy for anyone under 18.[83][48][84]

Psychosocial intervention

A systematic review assessed ten studies on the efficacy of psychosocial support interventions in transgender minors using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool and rated one as medium quality, and nine as low quality. The review said that no robust conclusions can be made and more research is needed.[46][85]

The report said the evidence for psychosocial interventions was "as weak as research on endocrine treatment".[86] It recommended that psychosocial interventions also form part of a research programme, along with endocrine interventions.[83]

Clinical pathways

The report said that clinicians cannot be certain which children and young people will have an enduring trans identity in adulthood, and that for most, a medical pathway will not be the most appropriate. When a medical pathway is clinically indicated, wider mental health or psychosocial issues should also be addressed. Due to a lack of follow-up, the number of individuals who detransitioned after hormone treatment was unknown.[87]

The Cass Review attempted to work with the Gender Identity Development Service and the NHS adult gender services to "fill some of the gaps in follow-up data for the approximately 9,000 young people who have been through GIDS to develop a stronger evidence base." However, despite encouragement from NHS England, "the necessary cooperation was not forthcoming."[88][89]

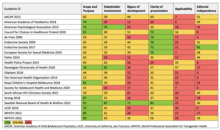

International guidelines

A systematic review assessed 23 regional, national and international guidelines covering key areas of practice, such as care principles, assessment methods and medical interventions. The review said most guidelines lacked editorial independence and developmental rigour, and were nearly all influenced by the 2009 Endocrine Society guideline and the 2012 WPATH guideline, which were themselves closely linked. The Cass review questioned the guidelines' reliability, and concluded that no single international guideline regarding transgender care could be applied in its entirety to NHS England.[90][50][51]

Conflicting clinical views

The report said there were conflicting views among clinicians regarding appropriate treatment. It suggested that disputes over language such as "exploratory"[i] and "affirmative"[j] approaches meant it was difficult to establish neutral terminology. Some clinicians avoided working with gender-questioning young people.[93] The report said some professionals were concerned about being accused of conversion therapy, and were likewise concerned about the impact of legislation to ban conversion therapy.[94][95]

Recommendations

The report made 32 recommendations covering areas including assessment of children and young people, diagnosis, psychological interventions, social transition, improving the evidence base underpinning medical and non-medical interventions, puberty blockers and hormone treatments, service improvements, education and training, clinical pathways, detransition and private provision.[96]

Recommendations included:

- Care provision:

- A designated medical practitioner who takes personal responsibility for the safety of children receiving care.[37]

- Individualised care plans, including mental health assessments and screening for neurodivergent conditions such as autism.[97]

- The use of standard psychological and pharmacological treatments for co-occurring and associated conditions like anxiety and depression.[98]

- That children and families considering social transition should be seen as soon as possible by a relevant clinical professional.[99]

- Longstanding gender dysphoria must be a prerequisite for medical transition, but is not the only criteria in deciding whether to allow a transition.[83]

- There should be a clear clinical rationale for the prescription of masculinising/feminising hormone therapy below the age of 18, and no masculinising/feminising hormone therapy below the age of 16.[83]

- Every case considered for medical transition must be discussed by a national multi-disciplinary team.[83]

- All minors should be offered fertility counselling and preservation prior to embarking upon a medical pathway.[83]

- A separate pathway should be established for the treatment of pre-pubertal treatment, who are ideally to be treated as early as possible.[100]

- Changing how the NHS provides care:

- The development of a regional network of centres, and continuity of care for 17–25 year olds.[101][29]

- The DHSC should direct NHS gender clinics to participate in the data linkage study, with the resulting research being overseen by NHS England's Research Oversight Board.[102]

- A multi-site service network should be developed as soon as possible, and the National Provider Collaborative to oversee the multi-disciplinary team should be established without delay.[103]

- To increase the available workforce, joint contracts should be used for health providers across a wide array of NHS services; and requirements for gender services should be built into the workforce planning for adolescent health services.[104]

- NHS England should develop a formal training program and competency framework for gender services, including a module on the holistic mental assessment framework.[105]

- Similar changes should be considered for adult gender services over the age of 25.[106]

- NHS England should "ensure there is provision for people considering detransition", which may require separate services.[107]

- The DHSC and NHS England should consider the implications of private healthcare on any future requests by patients for treatment under the NHS.[108]

- The DHSC should work to define the dispensing responsibilities of pharmacists receiving private prescriptions, and work to halt the sourcing of transition medication obtained through prescriptions acquired in Europe.[108]

- Future research:

- The establishment of a full program of research which will carefully study the characteristics, interventions, and outcomes of every person seen by NHS gender services.[83]

- A central evidence and data resource for gender services should be established, with specifically defined datasets for both local and national services.[105]

- National infrastructure should be put in place to manage continual data collection on gender services, including through the ages of 17 to 25.[105][106]

- A unified research strategy shall be established to ensure the most meaningful data and numbers are collected.[109]

- A living systematic review over all of this research should be collected.[100]

- The NHS should establish requirements for the collection of data from patients of NHS gender services.[110]

Implementation

NHS England responded positively to the interim and final reports. As of April 2024[update] they have implemented a number of measures.[5] In response to the interim report, in March 2024 NHS England announced that it would no longer prescribe puberty blockers to minors outside of use in clinical research trials, citing insufficient evidence of safety or clinical effectiveness.[111][112] The Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust closed in March 2024.[5] Two new services, located in the north west of England and in London, opened in April 2024, which are intended to be the first of up to eight regional services.[5] These will follow a new service specification for the "assessment, diagnosis and treatment of children and young people presenting with gender incongruence".[5] Puberty suppressing hormones are no longer routinely available in NHS youth gender services.[5] New patients that have been assessed as possibly benefiting from them will be required to participate in a clinical trial that is being set up by the National Institute for Health and Care Research.[36][113] A new board, chaired by Simon Wessely will encourage further research in the areas highlighted in the review as having a weak evidence base.[5]

On August 7, 2024, NHS England announced a status update, for young people being considered for referral to specialist gender services, including the publication of a new pathway specification.[114] One recommendation is that those considering social transition be seen quickly by a clinical professional with relevant experience. The update also stated that, as there is no defined clinical pathway for individuals considering detransition, NHS England will "establish a programme of work to explore the issues around a detransition pathway by October 2024".[115]

The clinical trial on puberty blockers for children and young people was due to start late 2024 but is now delayed to early 2025.[8]

Reception

Response from UK political parties and public bodies

Conservative Prime Minister at the time Rishi Sunak said that the findings "shine a spotlight" on the need for a cautious approach to child and adolescent gender care.[116][117] In their manifesto for the 2024 United Kingdom general election, the Conservatives promised to implement the Cass Review recommendations.[118]

Wes Streeting, the Labour shadow Health Secretary at the time, welcomed the final report, saying that the report was "a watershed moment for the NHS's gender identity services" and committing the Labour Party to implementing the report's recommendations in full.[119][120][121] Speaking to Sky News, Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper said that Labour welcomed the Cass Review and committed to implementing all of its recommendations.[122]

The Green Party of England and Wales described the Review as "an important part of the process of improving healthcare for children and young people" while saying "some concerns have been raised about the review, particularly in relation to accessing NHS care following private healthcare, concerns around data inclusion/exclusion and a question around a conflict of interest of one of the researchers."[123]

The Equality and Human Rights Commission, a non-departmental public body, described the Cass Review as a "vital milestone" and called for all service providers to fully implement its recommendations.[124]

Response from devolved governments

The Scottish Government said it would "take the time to consider the findings".[125] Humza Yousaf, First Minister of Scotland and SNP leader at the time, said the Scottish government would discuss the Cass Review with health authorities but would leave its implementation to clinicians.[126]

The Welsh Senedd initially voted against a motion tabled by the Welsh Conservatives Shadow Social Justice Minister to accept the findings of the Cass Review in full. Subsequently, the Senedd voted unanimously to pass an amended motion noting "NHS England has concluded there is not enough evidence to support the safety or clinical effectiveness of puberty suppressing hormones for the treatment of gender dysphoria in children and young people" and "the Welsh Government will continue to develop the transgender guidance for schools taking account of the Cass review and stakeholder views".[127]

Citing the Cass Review findings, in August 2024 the Northern Ireland Executive agreed to the extension of the ban on the private sale and supply of puberty blockers to Northern Ireland.[128] This was supported by all parties in the Executive at the time apart from the Alliance Party.[129]

Response from health bodies in the United Kingdom

In April 2024, the British Psychological Society (BPS) said they supported "the report's primary focus of expanding service capacity across the country" and acknowledged that "while psychological therapies will continue to have an incredibly important role to play in the new services, more needs to be done to assess the effectiveness of these psychological interventions." BPS president Roman Raczka said the review was "thorough and sensitive", and welcomed the recommendation for a consortium of relevant bodies to develop better trainings and upskill the workforce.[9]

The Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP) welcomed the report. They supported the emphasis on a holistic and person-centred approach and research to improve the evidence basis for treatment protocols. They said that some of its trans members, and the wider trans community, had concerns about availability of treatments while awaiting research, said there was "a strong view that the report makes assumptions in areas such as social transition and possible explanations for the increase in the numbers of people who have a trans or gender diverse identity, which contrasts with the more decisive statements about treatment approaches", and called for direct and comprehensive involvement of those with lived experience.[10]

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) said they would take the time to review the recommendations in full and said that data collected had identified a lack of confidence by paediatricians and GPs to support this patient group, which the RCPCH pledged to address by developing new training.[11] In August 2024, the RCPCH acknowledged there had been some academic criticism of the Cass Review and a call to pause the implementation of recommendations, but they said their priority is "that this group of children receive timely, holistic and high-quality care".[130]

In July 2024, the Royal College of General Practitioners updated its position statement on the role of the GP in transgender care in response to the Cass Review. They advise that, for patients under 18, GPs should not prescribe puberty blockers outside of clinical trials, and the prescription of gender-affirming hormones should be left to specialists. The GCGP says it will fully implement the Cass Review recommendations. They specifically highlight recommendations for continuity of care for 17–25 year olds, and the need for additional services for those people considering detransition.[12]

The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AoMRC) released a statement in August 2024 in support of the report's recommendations, stating that "further speculative work risks greater polarisation", and that "our focus should be on implementing the recommendations of the Cass Review".[13]

The British Medical Association (BMA) initially called for a pause on the review's implementation while it conducted an evaluation, due to be completed by January 2025.[18] In response, more than 1,500 doctors signed an open letter to the BMA characterising their planned evaluation as a "pointless exercise".[131][132] In September 2024, the BMA council voted to instead maintain a neutral position on the issue until the completion of its own evaluation.[133][134]

In April 2024, the British Association of Gender Identity Specialists (BAGIS) said it was "deeply troubled by some of the content of the Cass Review and the potential impact thereof". In December 2024, BAGIS also said it was "dismayed" to see the Department for Health and Social Care's "indefinite ban" on puberty blockers for under-18s, stating: "The Cass Review finds that puberty blockers have clearly defined benefits in narrow circumstances, which is inconsistent with a legislative ban".[135] The UK's Association of LGBTQ+ Doctors and Dentists (GLADD) issued a response to the Cass Review in November 2024. Of the 32 recommendations of the Cass Review, GLADD supported 15, and said that it could support a further 14 with provisos, could not support two, and was neutral on one. They did not criticise or appraise the methodology of the review, saying that they did not have "sufficient expertise to do justice to such evaluation."[136]

Response from other health bodies globally

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Endocrine Society both responded to the report by reaffirming their support for gender-affirming care for minors and saying that their current policies supporting such treatments are "grounded in evidence and science".[137]

The Canadian Pediatric Society said, "Current evidence shows puberty blockers to be safe when used appropriately, and they remain an option to be considered within a wider view of the patient's mental and psychosocial health."[138]

The Amsterdam University Medical Center said it agrees with the goals of reducing wait times and improving research, but disagrees that the research-base for puberty blockers is insufficient. It said that puberty blockers have been used in trans care for decades.[139]

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists rejected calls for an inquiry into trans healthcare following the release of the Cass Review, characterising it as one review among several in the field. They emphasised that, "assessment and treatment should be patient centred, evidence-informed and responsive to and supportive of the child or young person's needs and that psychiatrists have a responsibility to counter stigma and discrimination directed towards trans and gender diverse people."[140]

In August 2024, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology published updated guidelines on the treatment of gender dysphoria. The guidelines considered the Cass Review, describing it as specific to the unique situation in the UK, noted criticism of the Cass Review by other international organisations, and stated that the WPATH SOC8 considered more systematic reviews. The guidelines further said it is "self-evident" that, unless puberty is suppressed, development of sex characteristics are irreversible in AMAB individuals. The society stated they will continue to track and recommend prescriptions of puberty blockers in Japan to minors and expand to tracking discontinuations and switches to hormone therapy.[141][142]

Response from transgender specialist medical bodies

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) released an email statement saying the report is "rooted in the false premise that non-medical alternatives to care will result in less adolescent distress" and further criticised recommendations which "severely restrict access to physical healthcare, and focus almost exclusively on mental healthcare for a population which the World Health Organization does not regard as inherently mentally ill".[143][144] An official statement expanded on these concerns, saying Hilary Cass had "negligible prior knowledge or clinical experience" and that "the (research and consensus-based) evidence" suggests medical treatments such as puberty blockers and hormone therapy were "helpful and often life-saving". It questioned the provision of puberty blockers only in the context of a research protocol: "The use of a randomized blinded control group, which would lead to the highest quality of evidence, is ethically not feasible."[145]

The Professional Association for Transgender Health Aotearoa (PATHA), a New Zealand professional organisation, said the Cass Review made "harmful recommendations" and was not in line with international consensus. It suggested that "Restricting access to social transition is restricting gender expression, a natural part of human diversity". It also said trans or non-binary people were not included in the Cass Review's planning and decision-making – including clinicians experienced with affirmative care – while several people involved in the review had "previously advocated for bans on gender-affirming care" in the U.S., and had "promoted non-affirming 'gender exploratory therapy', which is considered a conversion practice". They said that trans people were excluded from the review's Governance Assurance Group "on the basis of potential bias".[16][146]

A joint statement by Equality Australia, signed by the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health (AusPATH) and PATHA among others, said the review "downplays the risk of denying treatment to young people with gender dysphoria and limits their options by placing restrictions on their access to care".[16][147][148]

Other academic responses

Some academics in the UK agreed with the Cass Review's findings stating a lack of evidence;[120][88][149] others, both in the UK[150] and internationally, disagreed with the report's methodology and findings.[138][151][152]

In July 2024, The Integrity Project at Yale Law School released a white paper which said the Cass Review had "serious flaws".[153][154][155] The white paper, co-authored by a group of eight legal scholars and medical researchers, suggests that the Cass Review "levies unsupported assertions about gender identity, gender dysphoria, standard practices, and safety of gender-affirming medical treatments, and it repeats claims that have been disproved by sound evidence". It concluded that the review "is not an authoritative guideline or standard of care, nor is it an accurate restatement of the available medical evidence on the treatment of gender dysphoria."[153][154]

In September 2024, the Journal of Adolescent Health, the peer-reviewed medical journal of the international Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, published a paper describing other scholars' "lengthy and nuanced rebuttals to the Cass report". The paper says that Cass' conclusions generally focus on "limiting or minimizing medical gender-affirming care (GAC) for youth" and that she "minimizes the robust data and the potential negative impact of increasing barriers for an already disenfranchised group". The paper states that "GAC for youth is well supported by evidence" and that concerns about the evidence base and the need for more research "do not warrant removal of access to this important care". The paper further suggests that randomised controlled trials (RCT) would not be ethically feasible for young people experiencing gender dysphoria.[156]

In November 2024, over 200 educational psychologists signed an open letter addressed to education secretary Bridget Phillipson. The letter expressed concerns about the "processes and findings of the Cass review" and the impact of the Cass Review on children and young people in education.[157] That same month, the healthcare division of the RAND Corporation (a US-based research institute), released its own systematic review into treatments for trans and gender expansive young people, in which it described several similarities and differences between its own approach and that of the Cass Review.[k] The report rated the existing evidence base as having low and very low certainty, but also found little evidence of side-effects, regret or dissatisfaction.[l] It said the Cass Review was "highly comprehensive", but said its findings may have limited applicability outside the context of the NHS.[m]

Reception by charities and human rights organisations

Amnesty International criticised "sensationalised coverage" of the review, stating it was "being weaponised by people who revel in spreading disinformation and myths about healthcare for trans young people".[161][162] Trans youth charity Mermaids and the LGBTQIA+ charity Stonewall endorsed some of the report's recommendations, such as expanding service provisions with the new regional hubs, but raised concerns the review's recommendations may lead to barriers for transgender youth in accessing care.[146]

Reception by gender-critical organisations

Gender-critical organisations including Sex Matters and Genspect welcomed the report. Stella O'Malley of Genspect said that if a conversion therapy ban were to criminalise any exploration into why a child identifies as trans, it "would ban the very therapy that Cass is saying should be prioritised".[163][164]

Hilary Cass's response

In the week after the release of the final report, Cass described receiving abusive emails and was given security advice to avoid public transport.[19] She said that "disinformation" had frequently been spread online about the report. Cass said deliberate attempts "to undermine a report that has looked at the evidence of children's healthcare" were "unforgivable" and put children at risk.[19] There were widespread misleading claims from critics of the report that it had dismissed 98% of the studies it collected and all studies which were not double-blind experiments.[20] Cass described these claims as being "completely incorrect". Although only 2% of the papers collected were considered to be of high quality, 60% of the papers, including those considered to be of moderate quality, were considered in the report's evidence synthesis.[43][165][166] Cass criticised Labour MP Dawn Butler for repeating inaccurate claims that the review had dismissed more than 100 studies during a debate in the House of Commons.[167][168][169] After talking with Cass, Butler used a point of order to admit her mistake and correct the record in Parliament, stating the figure came from a briefing she had received from Stonewall.[166][170][171][172]

In a May 2024 interview with The New York Times, Hilary Cass expressed concern that her review was being weaponised to suggest that trans people do not exist, saying "that's really disappointing to me that that happens, because that's absolutely not what we're saying". She also said that the review was not about defining what trans means or rolling back healthcare, stating: "There are young people who absolutely benefit from a medical pathway, and we need to make sure that those young people have access — under a research protocol, because we need to improve the research — but not assume that that's the right pathway for everyone."[21]

In a May 2024 interview with WBUR-FM, Cass responded to WPATH's criticism about prioritising non-medical care, saying the review did not take a position about which is best. Cass hoped that "every young person who walks through the door should be included in some kind of proper research protocol" and for those "where there is a clear, clinical view" that the medical pathway is best will still receive that, and be followed up to eliminate the "black hole of not knowing what's best". Responding to claims that the review assumed a trans outcome was the worst outcome for a child, Cass emphasised that a medical pathway, with lifetime implications and treatment, required caution but "it's really important to say that a cis outcome and a trans outcome have equal value".[173]

Subsequent government actions in the UK

Ban on puberty blockers outside clinical trials

In May 2024, then Health Secretary Victoria Atkins implemented an emergency three-month ban on the prescription of puberty blockers by medical providers outside of the NHS. It went into effect on 3 June 2024 and was set to expire on 3 September 2024. The ban restricted their use to those already taking them, or within a clinical trial. In July, this ban was challenged by campaign groups TransActual and the Good Law Project who brought a legal case arguing the ban was unlawful.[174] On 29 July 2024, the High Court of Justice ruled that the ban was lawful.[175][4][176]

The Health Secretary Wes Streeting welcomed the decision as “evidence led”, and said efforts were being made to set up a clinical trial to "establish the evidence on puberty blockers".[4][176] Following the ruling, TransActual announced they would not appeal the decision due to limited funds and the unlikelihood of an appeal being heard before the ban expires.[177]

On 22 August 2024, the government extended the emergency ban an additional three months and is now set to expire on 26 November 2024. The ban was also extended to cover Northern Ireland, following agreement from the Northern Ireland Executive and came into effect on 27 August 2024.[178][179][180] On 6 November 2024 the ban was extended again to 31 December 2024.[181] On 11 December 2024, the ban was renewed indefinitely and is set to be reconsidered in 2027.[182][183]

Adult clinics

The Cass Review did not cover adult care, but in April 2024, NHS England said it would also initiate a review of adult gender clinics.[184] NHS England National Director of Specialised Commissioning John Stewart sent a letter to Cass stating that it would review the use of transgender hormone therapy in adults in a similar manner as was done for puberty blockers in the Cass Review.[185][186][187]

In May 2024, Cass wrote to NHS England to pass on the feedback regarding adult care from clinicians who had approached her during the review process. Clinicians across the country in adult gender services had expressed concern about both the clinical practice and model of care. Some clinicians in other settings, especially general practice, had raised concerns about the treatment of patients under their care.[188] On 7 August, NHS England included a response to the adult care letter in a status report for the under-18s services.[189]

On 8 August, they stated the review of adult services would be led by Dr. David Levy, medical director for Lancashire and South Cumbria integrated care board, to assess "the quality (i.e. effectiveness, safety, and patient experience) and stability of each service, but also whether the existing service model is still appropriate for the patients it is caring for"; and that Dr. Levy would work with a group of "expert clinicians, patients and other key stakeholders, including representatives from the CQC, Royal Colleges and other professional bodies and will carefully consider experiences, feedback and outcomes from clinicians and patients, past and present". The first onsite visits are planned to start in September 2024. The findings will be used to support an updated adult gender service specification which will then be liable to engagement and public consultation. Unlike the Cass Review, the review of adult gender services is expected to be completed within months, rather than years.[6][190][191]

In December 2024, it was reported that a number of GPs had begun refusing or withdrawing hormone treatment from adult trans patients, for reasons including insufficient funds, GPs being "genuinely scared" about whether they can continue to offer the treatments due to the Cass Review, and the Royal College of GPs' response to the Cass Review – despite the Cass Review only applying to youth services.[192]

NHS Scotland

On 18 April 2024, NHS Scotland announced that it had paused prescribing puberty blockers to children referred by its specialist gender clinic.[193] The chief medical officer of Scotland set up a multidisciplinary clinical team to assess how the Cass Review's 32 recommendations might be applied to NHS Scotland. Their Cass Review – implications for Scotland: findings report was published in July 2024 and found that the majority of recommendations were applicable to NHS Scotland to a varying degree, with some modification dealing with differences in the Scottish health service. They recommended that the use of puberty blockers be paused until clinical trials are begun. NHS Scotland will participate in the forthcoming UK study.[194] That report was fully accepted by the Scottish government in September. Among the changes recommended are that the gender identity service for children and young people should be moved to a paediatric setting and more than one service offered across the regions. In common with other specialities, a referral to these services will now have to come from a clinician.[7]

Other government bodies’ actions

In October 2024, the Charity Commission for England and Wales released an inquiry into the trans children's charity Mermaids. The inquiry issued "regulatory advice and guidance" to the charity telling them to further consider the Cass Review's findings and conclusions as well as review the guidance and positions on their website regarding puberty blockers.[195]

See also

- 21st-century anti-trans movement in the United Kingdom

- Bell v Tavistock

- Evidence-based medicine

- Time to Think

- Transgender health care

- Transgender rights in the United Kingdom

- LGBTQ rights in the United Kingdom

- Transgender history in the United Kingdom

References

- ^ "NHS commissioning » Independent review into gender identity services for children and young people". NHS England (Primary source). Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "The Chair – Cass Review". Cass Independent Review (Primary source). Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Josh Parry; Hugh Pym (10 April 2024). "Hilary Cass: Weak evidence letting down children over gender care". BBC News (News). Archived from the original on 27 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ a b c "Puberty blockers ban is lawful, says High Court". BBC News. 29 July 2024. Archived from the original on 1 August 2024. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "NHS commissioning » Implementing advice from the Cass Review". www.england.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ a b "NHS England » NHS England update on work to transform gender identity services". www.england.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under an Open Government Licence v3.0 Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. © Crown copyright.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under an Open Government Licence v3.0 Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. © Crown copyright.

- ^ a b "Gender identity healthcare". www.gov.scot. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ a b Campbell, Denis (7 August 2024). "Delayed puberty blocker clinical trial to start next year in England". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ a b Stewart, John; Palmer, James (10 April 2024). "BPS responds to final Cass Review report". The British Psychological Society (Press release). Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b Smith, Lade (22 April 2024). "Detailed response to The Cass Review's Final Report" (Press release). Royal College of Psychiatrists. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ a b "RCPCH responds to publication of the final report from the Cass Review" (Press release). Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. 10 April 2024. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ a b "The role of the GP in transgender care" (Position statement). Royal College of General Practitioners. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Academy statement: Implementation of the Cass Review". Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (Statement). Archived from the original on 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b "WPATH, ASIAPATH, EPATH, PATHA, and USPATH Response to NHS England in the United Kingdom (UK): Statement regarding the Interim Service Specification for the Specialist Service for Children and Young People with Gender Dysphoria (Phase 1 Providers) by NHS England" (PDF) (Press release). 25 November 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ WPATH; EPATH (10 October 2023). "30.10.23 EPATH - WPATH Joint NHS Statement Final" (PDF). WPATH (Press release). Archived from the original on 11 April 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ a b c "Cass Review out of step with high-quality care provided in Aotearoa". PATHA – Professional Association for Transgender Health Aotearoa (Press release). 11 April 2024. Archived from the original on 11 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Cass Review' author: More 'caution' advised for gender-affirming care for youth". WBUR-FM. 8 May 2024. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b "BMA to undertake an evaluation of the Cass Review on gender identity services for children and young people" (Press release). British Medical Association. 31 July 2024. Archived from the original on 31 July 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Beal, James (19 April 2024). "Hilary Cass: I can't travel on public transport after gender report". The Times. Archived from the original on 20 April 2024. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ a b "It's misleading to say 100 studies were not included in the Cass Review". Full Fact. 20 May 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Hilary Cass Says U.S. Doctors Are 'Out of Date' on Youth Gender Medicine". The New York Times. 13 May 2024. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b Barnes, Hannah (30 March 2021). "The crisis at the Tavistock's child gender clinic". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 December 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ Gregory, Andrew; Thomas, Tobi; Gentleman, Amelia (10 April 2024). "What Cass review says about surge in children seeking gender services". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ Cohen, Deborah (9 December 2024). "Puberty blockers: Can a drug trial solve the big debate?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 December 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ Dyer, Clare (21 January 2021). "Gender dysphoria service rated inadequate after waiting list of 4600 raises concerns". BMJ: 1. doi:10.1136/bmj.n205.

- ^ Cass 2024, pp. 68–74. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCass2024 (help)

- ^ Koronka, Lucy Bannerman, James Beal, Eleanor Hayward, Poppy (9 April 2024). "Nine key findings from the Cass report into gender transition". The Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

The report finds that treatment on the NHS since 2011 has largely been informed by two sets of international guidelines, drawn up by the Endocrine Society and the World Professional Association of Transgender Healthcare (WPATH)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barnes, Hannah; Cohen, Deborah (22 July 2019). "Transgender treatment: Puberty blockers study under investigation". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Newton, Storm (10 April 2024). "Cass Review: What are the recommendations on child gender care?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ "RCGP calls for whole-system approach to improving NHS care for trans patients". Royal College of General Practitioners. 25 June 2019. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ Cass 2024, pp. 75–77. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCass2024 (help)

- ^ a b R. Dopp, Alex; Peipert, Allison; Buss, John; De Jesús-Romero, Robinson; Palmer, Keyton; Lorenzo-Luaces, Lorenzo (26 November 2024) [December 28, 2024]. Interventions for Gender Dysphoria and Related Health Problems in Transgender and Gender-Expansive Youth: A Systematic Review of Benefits and Risks to Inform Practice, Policy, and Research - RAND_RRA3223-1.pdf (PDF) (Report). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 26.

- ^ Grijseels, D. M. (8 June 2024). "Biological and psychosocial evidence in the Cass Review: a critical commentary". International Journal of Transgender Health: 1–3. doi:10.1080/26895269.2024.2362304.

- ^ a b Thornton, Jacqui (April 2024). "Cass Review calls for reformed gender identity services". The Lancet (News). 403 (10436): 1529. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00808-0. PMID 38643770.

Cass commissioned four systematic reviews of the evidence on key issues...

- ^ a b Cass review final report 2024, p. 28.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 56.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 8, Appendix 2.

- ^ "Homepage | Archives of Disease in Childhood". Archives of Disease in Childhood. Archived from the original on 19 December 2024. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Clayton, Alison; Amos, Andrew James; Spencer, Jillian; Clarke, Patrick (31 August 2024). "Implications of the Cass Review for health policy governing gender medicine for Australian minors". Australasian Psychiatry: 3. doi:10.1177/10398562241276335.

- ^ a b "Gender Identity Service Series". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Series of reviews commissioned to inform the Cass Review). Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ a b Mackintosh, Thomas (20 April 2024). "Cass Review: Gender care report author attacks 'misinformation'". BBC News (News). Archived from the original on 21 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b Taylor, Jo; Hall, Ruth; Langton, Trilby; Fraser, Lorna; Hewitt, Catherine Elizabeth (9 April 2024). "Characteristics of children and adolescents referred to specialist gender services: a systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s3 – s11. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326681. ISSN 0003-9888. PMID 38594046. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b Hall, Ruth; Mitchell, Alex; Taylor, Jo; Heathcote, Claire; Langton, Trilby; Fraser, Lorna; Hewitt, Catherine Elizabeth (9 April 2024). "Impact of social transition in relation to gender for children and adolescents: a systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s12 – s18. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326112. PMID 38594055. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ a b Heathcote, Claire; Mitchell, Alex; Taylor, Jo; Hall, Ruth; Langton, Trilby; Fraser, Lorna; Hewitt, Catherine Elizabeth; Jarvis, Stuart William (9 April 2024). "Psychosocial support interventions for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s19 – s32. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326347. PMID 38594045. Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Jo; Mitchell, Alex; Hall, Ruth; Heathcote, Claire; Langton, Trilby; Fraser, Lorna; Hewitt, Catherine Elizabeth (9 April 2024). "Interventions to suppress puberty in adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s33 – s47. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326669. ISSN 0003-9888. PMID 38594047. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b Taylor, Jo; Mitchell, Alex; Hall, Ruth; Langton, Trilby; Fraser, Lorna; Hewitt, Catherine Elizabeth (9 April 2024). "Masculinising and feminising hormone interventions for adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s48 – s56. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326670. ISSN 0003-9888. PMID 38594053. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Jo; Hall, Ruth; Langton, Trilby; Fraser, Lorna; Hewitt, Catherine Elizabeth (9 April 2024). "Care pathways of children and adolescents referred to specialist gender services: a systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s57 – s64. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326760. PMID 38594052. Archived from the original on 28 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ a b Taylor, J; Hall, R; Heathcote, C; Hewitt, CE; Langton, T; Fraser, L (9 April 2024). "Clinical guidelines for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review of guideline quality (part 1)". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s65 – s72. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326499. PMID 38594049. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b Taylor, J; Hall, R; Heathcote, C; Hewitt, CE; Langton, T; Fraser, L (9 April 2024). "Clinical guidelines for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review of recommendations (part 2)". Archives of Disease in Childhood (Review). 109 (Suppl 2): s73 – s82. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2023-326500. PMID 38594048. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 20, 47, 52–53.

- ^ Cass, Hilary (August 2024). "Gender identity services for children and young people: navigating uncertainty through communication, collaboration and care". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 225 (2): 302. doi:10.1192/bjp.2024.162.

The bedrock of the Review was a series of seven systematic reviews commissioned from the University of York

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 60.

- ^ Cass review interim report 2022, p. 15.

- ^ Brooks, Libby (10 March 2022). "NHS gender identity service for children can't cope with demand, review finds 10 March 2022". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ Bannerman, Lucy (10 March 2022). "Tavistock gender clinic not safe for children, report finds". The Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Cass review interim report 2022, p. 40.

- ^ Cass review interim report 2022, p. 18, 31.

- ^ Cass review interim report 2022, p. 18.

- ^ Cass review interim report 2022, p. 17.

- ^ Cass review interim report 2022, pp. 17, 19.

- ^ Crawford, Angus (23 April 2022). "Sajid Javid to review gender treatment for children" (News). BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Denis (12 March 2024). "Children to stop getting puberty blockers at gender identity clinics, says NHS England". The Guardian (News). Archived from the original on 12 March 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Parry, Josh (12 March 2024). "NHS England to stop prescribing puberty blockers". BBC News (News). Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Ghorayshi, Azeen (9 April 2024). "Youth Gender Medications Limited in England, Part of Big Shift in Europe". The New York Times (News). Archived from the original on 21 April 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Sajid Javid to review gender treatment for children". BBC News (News). 23 April 2022. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ CITEREFCass_review_final_report2024

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 20.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 33.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 114–121.

- ^ Martin, Daniel (8 April 2024). "Children must not be rushed to change gender, report warns". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 April 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ a b Bannerman, Lucy; Beal, James; Hayward, Eleanor; Koronka, Poppy (10 April 2024). "Nine key findings from the Cass review into gender transition". The Times. Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 161.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 32, 164.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 32, 164–5.

- ^ Thomas, Rebecca (10 April 2024). "Children failed by NHS amid toxic debate on gender identity, major review finds". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 176.

- ^ Parry, Josh; Pym, Hugh (9 April 2024). "Hilary Cass: Weak evidence letting down children over gender care". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 178.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cass review final report 2024, p. 35.

- ^ Gregory, Andrew; Davis, Nicola; Sample, Ian (10 April 2024). "Gender medicine 'built on shaky foundations', Cass review finds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 153.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 196.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024.

- ^ a b Abbasi, Kamran (11 April 2024). "The Cass review: an opportunity to unite behind evidence informed care in gender medicine". BMJ. 385: q837. doi:10.1136/bmj.q837. ISSN 1756-1833. Archived from the original on 11 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 27–8, 132.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 240.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 235.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 20, 202.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 150, 202.

- ^ Adu, Aletha; Gentleman, Amelia (11 April 2024). "Hilary Cass warns Kemi Badenoch over risks of conversion practices ban". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 28–45.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 29.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 30, 31.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 32.

- ^ a b Cass review final report 2024, p. 41.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, pp. 210, 224–225.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 34.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 37.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Cass review final report 2024, p. 39.

- ^ a b Cass review final report 2024, p. 42.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 43.

- ^ a b Cass review final report 2024, p. 44.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 40.

- ^ Cass review final report 2024, p. 45.

- ^ "NHS England to stop prescribing puberty blockers". BBC News. 12 March 2024. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ John, Tara (13 March 2024). "England's health service to stop prescribing puberty blockers to transgender kids". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ "Final report – FAQs – Cass Review". cass.independent-review.uk. Archived from the original on 28 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "NHS England » Referral pathway for specialist service for children and young people with gender incongruence". www.england.nhs.uk. 7 August 2024. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Searles, Michael (7 August 2024). "NHS to launch first service for trans patients wanting to return to birth gender". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 16 August 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "PM urges 'extreme caution' on gender treatments – as major review finds NHS failed children". Sky News (News). Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Cass review: Health secretary criticises gender care 'culture of secrecy'". BBC News (News). 11 April 2024. Archived from the original on 11 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ McKay, Lucy Brisbane (2 July 2024). "Explainer: what do the UK party manifestos say about trans+ issues?". The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ Crerar, Pippa (12 April 2024). "Cass review must be used as 'watershed moment' for NHS gender services, says Streeting". The Guardian (News). ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ a b Campbell, Denis; Gentleman, Amelia; Vinter, Robyn (10 April 2024). "Thousands of children unsure of gender identity 'let down by NHS', report finds". The Guardian (News). Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ Paul, Mark (10 April 2024). "British Labour says it will implement Cass findings on care for trans children if it wins election". The Irish Times (News). Archived from the original on 15 April 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "'How could we be giving kids puberty blockers for 20 years?' – Labour on Cass report". Sky News (News). 10 April 2024. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Green Party statement on the Cass review". 16 April 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ "Statement on the final report of the Cass Review" (Press release). Equality and Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 17 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Paton, Craig (10 April 2024). "Scottish Government pledges to consider findings of Cass Review into gender". The Independent (News). Archived from the original on 17 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Brooks, Libby (16 April 2024). "No case for closing Scotland's only NHS gender service clinic, says first minister". The Guardian (News). Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "MSs vote against adopting recommendations of Cass Review". nation.cymru. 2 May 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "Temporary ban on prescription and supply of puberty blockers extended to NI". Department of Health. 23 August 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Manley, John (23 August 2024). "Alliance isolated in Stormont executive as puberty blockers ban extended to Northern Ireland". The Irish News. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "Calls to evaluate the Cass Review - RCPCH response". RCPCH. 5 August 2024. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Hayward, Eleanor (27 August 2024). "BMA members resign in revolt over transgender children stance". www.thetimes.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2024. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Thornton, Jacqui (14–20 September 2024). "BMA members oppose its stance on the Cass Review". The Lancet (News). 404 (10457): 1004–1005. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01923-8. PMID 39278226. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "BMA takes 'neutral position' on gender review". BBC News. 27 September 2024. Archived from the original on 28 September 2024. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Barnes, Hannah (27 September 2024). "The BMA turns away from rejecting the Cass Report". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 27 September 2024. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ "Position & Process Statements: Initial BAGIS statement on the Cass Review". BAGIS. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ McGregor, Duncan (5 November 2024). "GLADD Response to The Cass Review" (PDF). Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "Cass Review' author: More 'caution' advised for gender-affirming care for youth". WBUR-FM (News). 8 May 2024. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b Johnson, Lisa (15 April 2024). "What Canadian doctors say about new U.K. review questioning puberty blockers for transgender youth". CBC (News). Archived from the original on 16 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Een reactie van Amsterdam UMC op de Cass review over transgenderzorg" (Press release). Amsterdam UMC. 18 April 2024. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Moore, Elizabeth (29 May 2024). "A letter from members regarding the Cass Review and the College's response". The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (Letter and reply). Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "性別不合に関する診断と治療のガイドライン (第 5 版)" (PDF). The Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology (in Japanese). August 2024. pp. 16–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2024. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "性別不合に関する診断と治療のガイドライン|公益社団法人 日本精神神経学会". www.jspn.or.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 1 October 2024. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Fiore, Kristina (16 April 2024). "Cass Review Finds Weak Evidence for Puberty Blockers, Hormones in Youth Gender Care". MedPage Today (News). Archived from the original on 27 April 2024. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Riedel, Samantha (12 April 2024). "Advocates Say a Controversial U.K. Report on Healthcare for Trans Kids Is "Fundamentally Flawed"". Them (News). Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "WPATH and USPATH Comment on the Cass Review" (PDF) (Press release). WPATH and USPATH. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ a b "How LGBTQIA+ charities are responding to the Cass review". Gay Times (News). 11 April 2024. Archived from the original on 11 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Cass Review out-of-line with medical consensus and lacks relevance in Australian context". Equality Australia (Press release). 10 April 2024. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Deor, Antimony (14 April 2024). "How Will The Cass Review Affect Aussie Trans Youth?". Star Observer (News). Archived from the original on 24 April 2024. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Bell, David (26 April 2024). "The Cass review of gender identity services marks a return to reason and evidence – it must be defended". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Vinter, Robyn (11 April 2024). "Trans children in England worse off now than four years ago, says psychologist". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "Contentious UK gender medicine report prompts reflection, outrage in Australia". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 12 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "NZ Government won't say if it will follow UK's move to ban routine use of puberty blockers as treatment for trans youth". The New Zealand Herald. 10 April 2024. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ a b Hunter, Ross (2 July 2024). "Cass Review contains 'serious flaws', according to Yale Law School". The National. Archived from the original on 2 July 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ a b Alfonseca, Kiara (9 July 2024). "New report critiques UK transgender youth care research study". ABC News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "White Paper Addresses Key Issues in Legal Battles over Gender-Affirming Health Care | Yale Law School". law.yale.edu. 1 July 2024. Archived from the original on 9 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ Budge, Stephanie L.; Abreu, Roberto L.; Flinn, Ryan E.; Donahue, Kelly L.; Estevez, Rebekah; Olezeski, Christy L.; Bernacki, Jessica M.; Barr, Sebastian; Bettergarcia, Jay; Sprott, Richard A.; Allen, Brittany J. (28 September 2024). "Gender Affirming Care Is Evidence Based for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth". Journal of Adolescent Health. 75 (6): 851–853. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2024.09.009. ISSN 1054-139X. PMID 39340502. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Perry, Sophie (12 November 2024). "Concerns over Cass Review raised by more than 200 educational psychologists". PinkNews. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ Dopp 2024, pp. 31–2.

- ^ Dopp 2024, pp. v–vi, 38.

- ^ Dopp 2024, p. 32.

- ^ "UK: Cass review on gender identity is being 'weaponised' by anti-trans groups". Amnesty International (Press release). 10 April 2024. Archived from the original on 12 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Alfonseca, Kiara (11 April 2024). "What the trans care recommendations from the NHS England report mean". ABC News (News). Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "The Cass Review damns England's youth-gender services". The Economist (News). 10 April 2024. Archived from the original on 16 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "The Cass Review is a damning indictment of what the NHS has been doing to children". Sex Matters. 9 April 2024. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Gecsoyler, Sammy (20 April 2024). "Hilary Cass warned of threats to safety after 'vile' abuse over NHS gender services review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b Beal, James (23 April 2024). "Cass author condemns 'misinformation' spread by trans lawyer". The Times. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Vickers-Price, Rachel (20 April 2024). "Hilary Cass says criticism of gender care review 'inaccurate' and 'unforgivable'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 28 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Hilary Cass says criticism of gender care review 'inaccurate' and 'unforgivable'". ITV News. 20 April 2024. Archived from the original on 20 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Cass Review: Gender report author cannot travel on public transport over safety fears". Sky News. 20 April 2024. Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Hansford, Amelia (24 April 2024). "Labour MP says she 'inadvertently misled' parliament on Cass report". PinkNews. Archived from the original on 24 April 2024. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ "Points of Order: Volume 748: debated on Monday 22 April 2024". Hansard. 22 April 2024. Archived from the original on 24 April 2024. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "It's misleading to say 100 studies were not included in the Cass Review". Full Fact. 20 May 2024. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "'The evidence was disappointingly poor': The full interview with Dr. Hilary Cass". www.wbur.org. WBUR-FM. 8 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Siddique, Haroon (12 July 2024). "Puberty blockers ban motivated by ex-minister's personal view, UK court told". theguardian.com. Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Streeting pushes ahead with NHS puberty blockers trial following high court ruling". The Independent. 29 July 2024. Archived from the original on 30 July 2024. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ a b Siddique, Haroon (29 July 2024). "Puberty blockers ban imposed by Tory government is lawful, high court rules". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ "TransActual will not appeal puberty blocker case". TransActual. 1 August 2024. Archived from the original on 16 August 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "The Medicines (Gonadotrophin-Releasing Hormone Analogues) (Emergency Prohibition) (Extension) Order 2024". UK Government. 22 August 2024. Archived from the original on 24 August 2024. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "Puberty blockers temporary ban extended". UK Government. 22 August 2024. Archived from the original on 24 August 2024. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "Puberty blocker ban extended to Northern Ireland". BBC. 23 August 2024. Archived from the original on 24 August 2024. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ "Extension to temporary ban on puberty blockers". GOV.UK. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (11 December 2024). "Puberty blockers to be banned indefinitely for under-18s across UK". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ Stephen Castle (11 December 2024). "U.K. Bans Puberty Blockers for Teens Indefinitely". New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ Searles, Michael; Donnelly, Laura; Martin, Daniel (9 April 2024). "NHS to review all transgender treatment". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 15 April 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Campbell, Denis; Gentleman, Amelia (10 April 2024). "Adult transgender clinics in England face inquiry into patient care". The Guardian (News). Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "NHS England's Response to the Final Report of the Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People". NHS England (Letter). 6 August 2024 [10 April 2024]. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Searles, Michael; Donnelly, Laura; Martin, Daniel (9 April 2024). "NHS to review all transgender treatment". The Telegraph (News). Archived from the original on 15 April 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Cass, Helen (16 May 2024). "Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People – Adult Gender Dysphoria Clinics" (PDF). NHS England. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "NHS England » NHS England update on work to transform gender identity services". www.england.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Review into safety of adult gender services to begin within weeks". The Independent. 7 August 2024. Archived from the original on 11 August 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Fox, Aine (7 August 2024). "Review into safety of adult gender services to begin within weeks". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 11 August 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "GPs halting transgender patients' hormone treatment or refusing prescriptions". The Independent. 7 December 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Scotland's under-18s gender clinic pauses puberty blockers". BBC (News). Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Improving gender identity healthcare". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ "Charity Inquiry: Mermaids". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

Works cited

- Cass, Hilary (10 March 2022). "Interim report – Cass Review". The Cass Review. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- Cass, Hilary (10 April 2024). "Final Report – Cass Review". The Cass Review. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

Endnotes

- ^ Between 2009–10 and 2019–20, the number of referrals increased from 77 to more than 2,700.[22][23][24][25]

- ^ Over time, the service adopted international standards from the Dutch Protocol and the WPATH and the Endocrine Society guidelines.[26][27]