Kayseri

Kayseri | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Mount Erciyes, Bürüngüz Mosque in Cumhuriyet Square, Sivas Street, Hunat Hatun Complex, Kayseri Castle, Kayseri Tram, Kadir Has Stadium | |

| Coordinates: 38°43′21″N 35°29′15″E / 38.72250°N 35.48750°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Central Anatolia |

| Province | Kayseri |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Memduh Büyükkılıç (AK Party) |

| Area | |

| 17,043 km2 (6,580 sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 3,620 km2 (1,400 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,810 km2 (1,080 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,050 m (3,440 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2021 estimate)[1] | |

| 1,434,357 | |

| • Density | 84/km2 (220/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,204,641 |

| • Urban density | 330/km2 (860/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,175,886 |

| • Metro density | 420/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

| GDP | |

| • Metropolitan municipality | TRY 107.378 billion US$ 11.956 billion (2021) |

| • Per capita | TRY 75,200 US$ 8,373 (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 38x xx |

| Area code | (+90) 352 |

| Licence plate | 38 |

| Website | kayseri |

Kayseri (Turkish pronunciation: [ˈkajseɾi]) is a large city in Central Anatolia, Turkey, and the capital of Kayseri province. Historically known as Caesarea, it has been the historical capital of Cappadocia since ancient times. The Kayseri Metropolitan Municipality area is composed of five districts: the two central districts of Kocasinan and Melikgazi, and since 2004, also outlying Hacılar, İncesu, and Talas.

As of 31 December 2021, the province had a population of 1,434,357 of whom 1,175,886 live in the four urban districts, excluding İncesu which is not conurbated, meaning it is not contiguous and has a largely non-protected buffer zone.

Kayseri sits at the foot of Mount Erciyes (Turkish: Erciyes Dağı), a dormant volcano that reaches an altitude of 3,916 metres (12,848 feet), more than 1,500 metres above the city's mean altitude. It contains a number of historic monuments, particularly from the Seljuk period. Tourists often pass through Kayseri en route to the attractions of Cappadocia to the west.

Kayseri is served by Erkilet International Airport and is home to Erciyes University.

Etymology

[edit]Kayseri was originally called Mazaka or Mazaca (Armenian: Մաժաք, romanized: Mažak'; according to Armenian tradition, it was founded by and named after Mishak)[3] and was known as such to the geographer Strabo, during whose time it was the capital of the Roman province of Cappadocia, known also as Eusebia at the Argaeus (Εὐσέβεια ἡ πρὸς τῷ Ἀργαίῳ in Greek), after Ariarathes V Eusebes, King of Cappadocia (r. 163–130 BC).

In 14 AD its name was changed by Archelaus (d. 17 AD), the last King of Cappadocia (r. 36 BC–14 AD) and a Roman vassal, to "Caesarea in Cappadocia" (to distinguish it from other cities with the name Caesarea in the Roman Empire) in honour of Caesar Augustus upon his death. This name was rendered as Καισάρεια (Kaisáreia) in Koine Greek, the dialect of the later Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire, and it remained in use by the natives (nowadays known as Cappadocian Greeks, due to their spoken language, but then referred to as Rum due to their previous Roman citizenship) until their expulsion from Turkey in 1924. (Note that letter C in classical Latin was pronounced K. This pronunciation was adapted by the Arabs, who called the city Kaisariyah (قيصرية), and the Turks, who gave the city its current name Kayseri (قیصری)).[4]

History

[edit]

Kayseri experienced three golden ages. The first, dating to 2000 BC, was when the city formed a trade post between the Assyrians and the Hittites. The second came under Roman rule from the 1st to the 11th centuries. The third golden age was during the reign of the Seljuks (1178–1243), when the city was the second capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum.

Ancient history

[edit]As Mazaca (Ancient Greek: Μάζακα),[5] the city served as the residence of the kings of Cappadocia. In ancient times, it was on the crossroads of the trade routes from Sinope to the Euphrates and from the Persian Royal Road that extended from Sardis to Susa during the 200+ years of Achaemenid Persian rule. In Roman times, a similar route from Ephesus to the East also crossed the city.

In Late Antiquity, the city may have contained a population of around 50,000 inhabitants and it was the highest ranked diocese up to the council of Chalcedon.[6] Nothing remains of it today. Basil of Caesarea, one of the Cappadocian Fathers, established a large complex containing charitable institutions, a monastery and churches, the Basiliad, in Caesarea Mazaca in the fourth century.[7] Nothing remains of it today.

The city was also situated on the main pilgrimage route from Constantinople to the Holy Land and had several shrines dedicated to local saints, such as St Mamas, St Merkourious and Basil of Caesarea, which continued to be venerated by the local population into the 17th century.[7] The city was occupied by the Sassanids in 611/12 in the last war between the Byzantines and the Sassanids and became the headquarter of emperor Heraclius.[6]

The city stood on a low spur on the north side of Mount Erciyes (Mount Argaeus in antiquity). Very few traces of the ancient site now survive.

Medieval history

[edit]From the mid-seventh century onwards, Arab attacks on Cappadocia and Caesarea became common and the city was besieged several times, diminishing in population and resources consequently.[8] The Arab general, and later the first Umayyad Caliph, Muawiyah invaded Cappadocia and took Caesarea from the Byzantines temporarily in 647.[9] By the mid-eight century, the area between Caesarea and Melitene was a no-mans land.[8]

Though the city lost most of its importance by the tenth century, is housed probably still around 50,000 people.[10] Alp Arslan's forces demolished the city and massacred its population in 1067.[11] The shrine of Saint Basil was also sacked after the fall of the city.[12] As a result, the city remained uninhabited for the next half century.[11]

From 1074 to 1178 the area was under the control of the Danishmendids who rebuilt the city in 1134.[13] The Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate controlled the city from 1178 to 1243 and it was one of their most important centres until it fell to the Mongols in 1243. The relatively short Seljuk period left a large number of historic landmarks including the Hunat Hatun Complex, the Kiliç Arslan Mosque, the Ulu Camii (Grand Mosque) and the Gevher Nesibe Hastanesi (Hospital). Within the walls lies the greater part of Kayseri, rebuilt between the 13th and 16th centuries. The city then fell to the Eretnids before finally becoming Ottoman in 1515. It was the centre of a sanjak called initially the Rum Eyalet (1515–1521) and then the Angora vilayet (founded as Bozok Eyalet, 1839–1923).

Modern era

[edit]

The Grand Bazaar dates from the latter part of the 1800s, but the adjacent caravanserai, where merchant traders gathered before forming a caravan, dates from around 1500. The town's older districts which were filled with ornate mansion-houses mostly dating from the 18th and 19th centuries were subjected to wholesale demolition starting in the 1970s.[14]

The building that hosted the Kayseri Lyceum was rearranged to host the Turkish Grand National Assembly during the Turkish War of Independence when the Greek army was advancing on Ankara, the base of the Turkish National Movement.

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]Kayseri has a continental climate (Köppen: Dsa, Trewartha: Dc). It experiences cold, snowy winters and hot, dry summers with cool nights. Precipitation occurs throughout the year, albeit with a marked decrease in late summer and early fall.

| Climate data for Kayseri (1991–2020, extremes 1931–2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.3 (66.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.6 (99.7) |

40.7 (105.3) |

40.6 (105.1) |

38.4 (101.1) |

33.6 (92.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

0.5 (32.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

0.8 (33.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.4 (22.3) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

3.9 (39.0) |

7.6 (45.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

4.1 (39.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.5 (−26.5) |

−31.2 (−24.2) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.9 (37.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−28.4 (−19.1) |

−32.5 (−26.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.0 (1.50) |

38.9 (1.53) |

49.6 (1.95) |

46.9 (1.85) |

57.9 (2.28) |

40.6 (1.60) |

11.9 (0.47) |

9.5 (0.37) |

14.0 (0.55) |

32.3 (1.27) |

29.3 (1.15) |

39.3 (1.55) |

408.2 (16.07) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.6 | 11.5 | 12.67 | 12.13 | 13.27 | 9.43 | 2.17 | 1.77 | 3.87 | 7.67 | 7.73 | 11.17 | 104.98 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.9 | 71.5 | 64.3 | 58.9 | 58.9 | 54.5 | 46.6 | 46.7 | 50.5 | 61.6 | 68.1 | 75.3 | 61.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 89.9 | 113.0 | 145.7 | 183.0 | 248.0 | 300.0 | 356.5 | 341.0 | 255.0 | 195.3 | 141.0 | 83.7 | 2,452.1 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.9 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 11.5 | 11.0 | 8.5 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 6.7 |

| Source 1: Turkish State Meteorological Service[15] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity, 1991–2020)[16] | |||||||||||||

Political structure

[edit]

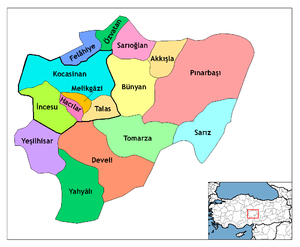

The city of Kayseri consists of sixteen metropolitan districts: Akkışla, Bünyan, Develi, Felâhiye, Hacılar, İncesu, Kocasinan, Melikgâzi, Özvatan, Pınarbaşı, Sarıoğlan, Sarız, Talas, Tomarza, Yahyâlı, and Yeşilhisar.

Local attractions

[edit]In Kayseri

[edit]

Kayseri features a range of historical and cultural attractions that reflect the city's heritage. Cumhuriyet Square is a central public space in Kayseri, surrounded by notable buildings. Inside the centre of Kayseri the most unmissable reminder of the past are the huge basalt walls that once enclosed the old city. Dating back to the sixth century and the reign of the Emperor Justinian, they have been repeatedly repaired, by the Seljuks, by the Ottomans and more recently by the current Turkish government.[17] In 2019 Kayseri Archaeology Museum moved from an outlying location to a new site inside the walls.[18] Kayseri Clock Tower, built in the early 20th century by Abdülhamid II, is located in the city center and remains a recognizable landmark. Bürüngüz Mosque, constructed in the 13th century, is an example of Seljuk architecture and is still in use today.

Surp Asdvadzadzin Virgin Mary Church Research Library, located within the Surp Asdvadzadzin Church. The Atatürk House Museum is located in a house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk stayed, providing historical context about the early years of the Turkish Republic. The National Struggle Museum focuses on the history of the Turkish War of Independence and the role of Kayseri in the formation of the modern Turkish state.

The Grand Mosque (Turkish: Ulu Cami) was started by the Danişmend emir Melik Mehmed Gazi who is buried beside it although it was only completed by the Seljuks after his death.[17] There are many magnificent reminders of the Seljuk supremacy in and around the walls as well as many much smaller kümbets (domed tombs) of which the most impressive is the Döner Kümbet (lit. Revolving Tomb). The oldest surviving Seljuk place of worship – and the oldest Seljuk mosque built in Turkey – is the Hunat Hatun Mosque Complex which still includes a functioning hamam with separate sections for men and women dating back to 1238.[17]

Near the mosque is the Sahabiye Medresesi, a theological school dating back to 1267 with a magnificent portal typical of Seljuk architecture.[17] Very similar is the Avgunlu Medresesi which now serves as a large bookshop-cum-cafe in a park. In Mimar Sinan Park stands the Çifte Medresesi, a pair of Seljuk-era theological schools that eventually served as a hospital for those with psychiatric disorders. They were commissioned by the Seljuk sultan Giyasettin I Keyhüsrev and his sister, Gevher Nesibe Sultan, who is buried inside. Today the buildings house the Museum of Seljuk Civilisations.[17][19]

Another Seljuk survivor is the grand Halikılıç Mosque complex which has two spectacular entrance portals. It dates back to 1249 but was extensively restored three centuries later.[17] Post-dating the Seljuks is the Güpgüpoğlu Mansion which dates back to the early 15th century but is open to the public with the furnishings it would have had in the late 19th century when it was home to the poet and politician Ahmed Midhad Güpgüpoğlu.[17]

Close to the walls is Kayseri's own Kapalı Çarşı (Turkish: Kapalı Çarşı), still a bustling commercial centre selling cheap clothes, shoes and much else. Deep inside it is the older and very atmospheric Vezir Han which was commissioned in the early 18th century by Nevşehir-born Damad İbrahim Paşa who became a grand vizier to Sultan Ahmed III before being assassinated in 1730.[17]

Around Kayseri

[edit]The Kayseri suburb of Talas was the ancestral home of Calouste Gulbenkian, Aristotle Onassis and Elia Kazan. Once ruinous following the expulsion of its Armenian population in 1915 and then of its Greek population in 1923, it was largely reconstructed in the early 21st century. The Greek Orthodox Church of Saint Mary, built in 1888, has been converted into the Yaman Dede Mosque.[20] Similarly attractive is the suburb of Germir, home to three 19th-century churches and many fine old stone houses.[21]

Mount Erciyes (Turkish: Erciyes Dağı) looms over Kayseri and serves as a trekking and alpinism centre. During the 2010s an erstwhile small, local ski resort was developed into more of an international attraction with big-name hotels and facilities suitable for all sorts of winter pastimes.[22][23]

The archaeological site of Kanesh-Kültepe, one of the oldest cities in Asia Minor, is 20 km northeast of Kayseri.[24]

Ağırnas, a small town with many lovely old houses, was the birthplace in 1490 of the great Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, and a house traditionally associated with him is open to the public as a museum. Beneath it there is one of the 'underground cities' so typical of Cappadocia. The restored Church of Saint Procopius dates back to 1857 and serves as a cultural centre.[25]

The small town of Develi also contains some attractive old houses. The 19th-century Armenian Church of Saint Mary has been turned into the Lower Everek Mosque (Turkish: Aşağı Everek Cami).[26]

Economy

[edit]Kayseri received notable public investments in the 1920s and 1930s. Sümer Fabric Factory and Kayseri Tayyare Fabrikası (English: Kayseri Aeroplane Factory) were set up here in the Republican Era with the help of German and particularly Russian experts. The latter manufactured the first aircraft made in Turkey in the 1940s. After the 1950s, the city suffered from a decrease in the amount of public investment. It was, however, during the same years that Kayseri businessmen and merchants transformed themselves into rural capitalists. Members of Turkish business families such as Sabancı, Has, Dedeman, Hattat, Kurmel, Özyeğin, Karamanlargil and Özilhan started out as small-scale merchants in Kayseri before becoming prominent actors in the Turkish economy. Despite setting up their headquarters in cities such as Istanbul and Adana, they often returned to Kayseri to invest.

Thanks to the economic liberalisation policies introduced in the 1980s, a new wave of merchants and industrialists from Kayseri joined their predecessors. Most of these new industrialists choose Kayseri as a base of their operations. As a consequence of better infrastructure, the city has achieved remarkable industrial growth since 2000, causing it to be described as one of Turkey's Anatolian Tigers.[27]

The pace of growth of the city was so fast that in 2004 the city applied to the Guinness Book of World Records for the most new manufacturing industries started in a single day: 139 factories. Kayseri also has emerged as one of the most successful furniture-making hub in Turkey earned more than a billion dollars in export revenues in 2007. Its environment is regarded as especially favourable for small and medium enterprises.

Kayseri Free Zone established in 1998 now has more than 43 companies with an investment of 140 million dollars. The Zone's main business activities include production, trading, warehouse management, mounting and demounting, assembly-disassembly, merchandising, maintenance and repair, engineering workshops, office and workplace rental, packing-repacking, banking and insurance, leasing, labelling and exhibition facilities. Kayseri FTZ is one of the cheapest land free zones in the world.[28]

A group of social scientists have traced the economic success of Kayseri, a city in central Turkey, to a modernist Islamic outlook referred to as "Islamic Calvinism."[29] This concept is drawn from Max Weber's influential 1905 essay, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which argued that the "this-worldly asceticism" of Calvinism was the driving force behind the development of modern capitalism. In a similar vein, these scholars suggest that the religious and cultural practices in Kayseri, rooted in a modern interpretation of Islam, fostered values such as hard work, thrift, and entrepreneurial spirit, which contributed to the city's economic growth.[30] In Kayseri, a notable characteristic of the local culture is a form of austerity, which can be observed alongside a strong work ethic. According to an op-ed in The Irish Times, "The city's streets are not crowded with luxury cars, and the homes in its wealthiest neighborhoods are relatively modest compared to European standards. Rather than conspicuous consumption, wealth is often reinvested into the community."[31] Philanthropy plays an important role in the city, aligning with the Islamic emphasis on charity. Kayseri is known for its privately funded institutions, including schools, clinics, sports facilities, and community centers, reflecting a focus on communal support and development.[31]

Transport

[edit]The city is served by Erkilet International Airport (ASR) which is a short distance from the centre of Kayseri. It offers several flights a day to Istanbul.

Kayseri is connected to the rest of country by rail services. There are four trains a day to Ankara. To the east there are two train routes, one to Kars and the other to Tatvan at the western end of Lake Van.

As the city is located in central Turkey, road transportation is very efficient. It takes approximately three hours to reach Ankara, the same to the Mediterranean coast and 45 minutes to Cappadocia. A notable ski resort in winter and accessible for trekking in summer, Mt Erciyes is 30 minutes from the city centre.

Within the city transportation largely relies on buses and private vehicles although there is also a light rail transit (LRT) system called Kayseray which runs to the inter-city bus terminal and to Talas.[32]

Sports

[edit]

The city had two professional football teams competing in top-flight Turkish football. Kayserispor and Kayseri Erciyesspor simultaneously play in the Süper Lig, making Kayseri one of only two cities having more than one team in Spor Toto Süper Lig 2013–14 (the other being Istanbul). In 2006 Kayserispor became the only Turkish team to have won the UEFA Intertoto Cup. Kayserispor is the remaining professional team in the city, playing in the top flight as of 2023.

The Erciyes Ski Resort on Mount Erciyes is one of the largest ski resorts in Turkey.

The women's football club Kayseri Gençler Birliği was promoted to the Women's First League for the 2020–21 League season.[33]

Sports venues

[edit]- Kadir Has Stadium is a new generation stadium located in the outskirts of the city. Completed in early 2009, the all-seater stadium has a capacity of 33,000 spectators and is totally covered. It is shared by the two Kayseri football clubs. The stadium and surrounding sports complex are served by the light-rail system, Kayseray. The stadium was inaugurated with a Kayserispor – Fenerbahce league match. Kadir Has Stadium was one of eight host stadiums for the 2013 FIFA U-20 World Cup. It hosted the opening ceremony and the opening match between Cuba and the Republic of Korea.

- Kadir Has Sports Arena is an indoor arena opened in 2008. It has seating capacity for 7,200 people. Together with Kadir Has Stadium, it is a part of the Kayseri Kadir Has Sports Complex, one of Turkey's most modern sports complexes. It was one of the venues for the 2010 FIBA World Championship.

Education

[edit]

Kayseri High School (Ottoman Turkish: Kayseri Mekteb-i Sultanisi,[34] lit. the Imperial School of Kayseri), founded in 1893, is one of Turkey's oldest high schools. It has a long history of providing quality education and has played a key role in the region's educational development.[35] Nuh Mehmet Küçükçalık Anadolu Lisesi, established in 1984, offers education in English.[36] TED Kayseri College, founded in 1966, is a private, non-profit school in the Kocasinan district, serving kindergarten through high school.[37] Middle East Technical University Development Foundation Kayseri College follows METU's educational philosophy, offering a comprehensive curriculum.[38] Talas American College, established in 1871, has a rich legacy as an American school and continues to influence the region's education.[39] Although the school is no longer active, its historical contributions to education in Kayseri continue to be remembered.[40]

Kayseri is home to four public universities and one private university. Abdullah Gül University, established in 2010, is the first public university in Turkey with legal provisions for support by a philanthropic foundation dedicated entirely to its work.[41] Erciyes University, founded in 1978, is the city's largest research university. It currently has 13 faculties, six colleges, and seven vocational schools, with over 3,100 staff members and 41,225 students.[42] Nuh Naci Yazgan University, founded in 2009, is the only private university in the region. Kayseri University, established more recently, contributes to the city's academic landscape with a focus on a diverse curriculum. University of Health Sciences Kayseri Medical School also plays a significant role in the city's educational offerings, providing specialized medical training and research opportunities.[43] These institutions collectively contribute to Kayseri's growing reputation as an educational hub.

Cuisine

[edit]

Kayseri's cuisine includes several traditional dishes that are characteristic of the region. Mantı, a small dumpling filled with minced meat and commonly served with yogurt and spiced butter, is one of the city's signature dishes. Known for its fine preparation, Kayseri-style mantı is distinguished by the small size of the dumplings. Pastırma is a type of air-dried, cured beef, seasoned with a paste made from garlic, fenugreek, and spices. It is often thinly sliced and served as an appetizer or used in other dishes. Sucuk, a dry, fermented sausage made from ground beef and seasoned with garlic and red pepper, is another popular specialty in the region and is commonly included in breakfasts or cooked with eggs.

Stuffed zucchini flowers are a seasonal dish prepared with a filling of minced meat, garlic, and spices. The flowers are carefully stuffed and then baked or steamed. This dish highlights the use of locally sourced ingredients in Kayseri's cuisine. Nevzine is a traditional dessert made from tahini, molasses, and walnuts, soaked in syrup. This dessert is typically prepared for special occasions and is notable for its dense texture and flavor profile.

Image gallery

[edit]-

Döner Kümbet, a 13th-century Seljuk tomb, notable for its octagonal shape and intricate stone carvings.

-

Kadir Has Stadium, a football stadium in Kayseri.

-

Kadir Has Stadium, a football stadium in Kayseri.

-

Kadir Has Stadium, a football stadium in Kayseri.

-

An interior view of Kadir Has Stadium.

-

Forum Kayseri, a shopping center featuring retail stores, dining options, and entertainment facilities.

-

A panoramic view of Kayseri.

-

Kayseri Clock Tower, a historic clock tower located in the city center.

-

A historic house in Kayseri, showcasing the region's traditional architecture.

-

Erciyes University, a major research university in Kayseri.

-

Hunat Hatun Medresesi, a 13th-century Islamic school and complex.

-

Statue of an Assyrian Tablet, a replica of an ancient Assyrian tablet displayed in Kayseri.

-

Mount Erciyes, a prominent volcanic mountain near Kayseri, known for its ski resort and hiking trails.

-

Kayseri Ethnography Museum, a museum focuses the region's cultural heritage.

Notable people

[edit]-

Güler Sabancı, CEO of Sabancı Holding

-

Alparslan Türkeş, Politician, founder of the Nationalist Movement Party

-

Nuri Demirağ, Turkish railway magnate and industrialist

-

Elia Kazan, American film director, producer and co-founder of Actors Studio

- Nuri Demirağ (1883–1957), Turkish engineer, businessman and politician of founder in Millî Kalkınma Partisi

- Naci Demirağ (1890–1944), Turkish engineer and businessman

- Mimar Sinan (1488–1588), the chief Ottoman architect for Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II and Murad III

- Calouste Gulbenkian (1869–1955), British-Armenian businessman and philanthropist, shareholder of Royal Dutch Shell

- Nubar Gulbenkian (1896–1972), British-Armenian business magnate and socialite

- Atilla Engin (1946-2019), Turkish-American fusion jazz drummer

- Hagop Kevorkian (1872-1962), Armenian-American archeologist, connoisseur of art, and collector

- Basil of Caesarea (330–378), Early Roman Christian prelate, one of the Cappadocian Fathers and Doctor of the Church

- Kadi Burhan al-Din (1345–1398), Vizier to the Eretnid rulers of Anatolia

- Ferruh Güpgüp (1891-1951), Turkish politician, one of the first women parliament members of Turkey

- Konstantinos Adosidis, (1818–1895), Ottoman-appointed Prince of Samos from 1873 to 1874

- Turhan Feyzioğlu (1922–1988), Turkish constitutional law professor, politician and founding rector of METU

- Mehmet Burak Erdoğan (1972-), Turkish mathematician at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

- Kadir Bal (1966-), Turkish bureaucrat, diplomat, and engineer

- Aristotle Onassis (1906–1975), Greek business magnate[44]

- Ziya Müezzinoğlu (1919-2020), Diplomat and former Turkish Minister of Finance, Minister of Commerce

- Arthur H. Bulbulian (1900-1996), Armenian-American physician and inventor

- Paisios of Mount Athos (1924–1996), Well-known Eastern Orthodox ascetic and Athonite monk

- Mehmet Kemal Dedeman (1903–1998), Turkish businessman and founder of the Dedeman Group of Companies

- Carrie Farnsworth Fowle (1854-1917), American missionary

- Hasan Kaçan (1957–), Turkish actor, screenwriter and caricaturist for Gırgır, Cumhuriyet, Hıbır, Ustura, Yeni Şafak

- Metin Kaçan (1961–2013), Turkish male writer of Ağır Roman and brother Hasan Kaçan

- Hulusi Akar (1952–), Turkish soldier and politician in the former of General Staff of the Turkish Armed Forces president, former Ministry of National Defense (Turkey) minister and in the 28th AK Party Kayseri member of parliament

- Şule Yüksel Şenler (1938–2019), Turkish Islamist women writer, poet, senarist and Islamic democracy activist

- Vahan Cardashian (1882-1934), Armenian-American political activist and lawyer

- Hacı Ömer Sabancı (1906–1966), Turkish businessperson and founder of Sabancı Holding

- Teodor Kasap (1835–1897), Ottoman Greek newspaper editor and educator

- İhsan Ketin (1914–1995), Turkish earth scientist

- Pavlos Karolidis (1849-1930), Greek historian

- Nikolaos Alektoridis (1874–1909), Greek painter and a member of the Munich School

- Hüsnü Özyeğin (1944–), Turkish businessperson, founder of Finansbank and Özyeğin University

- Hasan Nasil Canat (1943–2004), Turkish actor

- Emmanouil Emmanouilidis (1867-1943), Ottoman Greek MP for the Committee of Union and Progress

- Krikor Balyan (1764–1831), Patriarch of the Armenian Balyan Family of Ottoman court architects

- Berna Gözbaşı (1974–), Turkish businesswoman and the president of Kayserispor

- Missak Kouyumjian (1877-1913), Armenian poet

- Sakıp Sabancı (1933–2004), Turkish businessman and the billionaire in former CEO of Sabancı Holding

- Güler Sabancı (1955–), Turkish businesswoman and CEO of Sabancı Holding

- İzzet Özilhan (1920–2014), Turkish businessman and founder of Anadolu Grubu

- Kadir Has (1931–2007), Turkish businessman

- Halit Cıngıllıoğlu (1954–), Turkish banker, industrialist and contemporary art collector

- Alparslan Türkeş (1917–1997), Turkish soldier and politician in founder of Nationalist Movement Party in ideology Idealism

- Mehmet Topuz, Turkish footballer

- Tuncay Özilhan (1947–), Turkish businessman and the CEO of Anadolu Group

- Asım Kibar (1933–), Turkish businessman and founder of Hyundai Assan Otomotiv

- Elia Kazan (1909–2003), American film director, producer and co-founder of Actors Studio

- Tuğrul Türkeş (1954–), Turkish economist, academician and politician in founder of Bright Turkey Party

- Hüsamettin Özkan (1950–), Turkish politician, former Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey

- Hayrünnisa Gül (1965–), 11th First Lady of Turkey

- Abdullah Gül (1950–), 11th President of Turkey

Kayseri metropolitan municipality mayors

[edit]- 1984 – 1989 Hüsamettin Çetinbulut (ANAP)

- 1989 – 1994 Niyazi Bahçecioğlu (SHP)

- 1994 – 1998 Şükrü Karatepe (Welfare Party, Virtue Party)

- 1998 – 2015 Mehmet Özhaseki (Virtue Party, AK Party)

- 2015 – Memduh Büyükkılıç (AK Party)

Twin towns

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Turkey: Administrative Division (Provinces and Districts) – Population Statistics, Charts and Map". Citypopulation.de.

- ^ "Statistics by Theme > National Accounts > Regional Accounts". www.turkstat.gov.tr. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ Olmstead, A. T. (1929). "Two Stone Idols from Asia Minor at the University of Illinois". Syria. 10 (4): 311–313. doi:10.3406/syria.1929.3413. JSTOR 4236961. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (2005). "Kayseri". Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ "Strabo, Geography, Book 12, chapter 2, section 7". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ a b Cooper, Eric; Decker, Michael J. (24 July 2012). Life and Society in Byzantine Cappadocia. Springer. p. 16;47. ISBN 978-1-137-02964-5. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ a b Cooper, Eric; Decker, Michael J. (24 July 2012). Life and Society in Byzantine Cappadocia. Springer. pp. 30, 166, 168–169. ISBN 978-1-137-02964-5. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ a b Cooper, Eric; Decker, Michael J. (24 July 2012). Life and Society in Byzantine Cappadocia. Springer. pp. 22–23, 226, 239. ISBN 978-1-137-02964-5. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1969. Pg 116.

- ^ Cooper, Eric; Decker, Michael J. (24 July 2012). Life and Society in Byzantine Cappadocia. Springer. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-137-02964-5. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ a b Ash, John (2006). A Byzantine journey ([2. ed.] ed.). London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 167. ISBN 9781845113070.

In that year the Turks captured Caesarea, the chief city of eastern Cappadocia, burnt it to the ground, massacred its inhabitants and descrated the great shrine of Saint Basil.

- ^ Vaughan, Louis Bréhier; translated by Margaret (1977). The life and death of Byzantium. Amsterdam: North-Holland Pub. Co . p. 193. ISBN 9780720490084.

In the spring of 1067 he invaded the Pontus and penetrated as far as Caesarea in Cappadocia which he demolished

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Speros Vryonis, Vryonis Decline of Medieval Hellinism in Asia Minor | PDF | Anatolia | Byzantine Empire The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century. Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine (University of California Press, 1971), p. 155

- ^ "Armenian Architecture – VirtualANI – The Traditional Houses of Kayseri". Virtualani.org. Archived from the original on 2007-05-23.

- ^ "Resmi İstatistikler: İllerimize Ait Mevism Normalleri (1991–2020)" (in Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Kayseri Bolge-17196" (CSV). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "KAYSERİ". www.turkeyfromtheinside.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "Kayseri Archaeology Museum" (PDF).

- ^ "Museum of Seljuk Civilisation | Kayseri, Turkey | Attractions – Lonely Planet". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "TALAS". www.turkeyfromtheinside.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "GERMİR". www.turkeyfromtheinside.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "Erciyes Ski Resort". www.kayserierciyes.com.tr. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "ERCİYES DAĞI (MT ERCIYES)". www.turkeyfromtheinside.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "KÜLTEPE". www.turkeyfromtheinside.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "AĞIRNAS". www.turkeyfromtheinside.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "DEVELİ". www.turkeyfromtheinside.com. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ ESI. "Islamic Calvinists: Change and Conservatism in Central Anatolia" (PDF). European Stability Initiative, Berlin. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-12-10. Retrieved 2005-09-19.

- ^ "KAYSER -Kayseri Serbest Bölgesi". Archived from the original on 2013-12-05.

- ^ "Chronology of all ESI publications – Reports – ESI". Esiweb.org. 2005-09-19. Archived from the original on 2012-06-03. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ "Islamic Calvinists: Change and Conservatism in Central Anatolia" (PDF). European Stability Initiative.

- ^ a b "Islamic Calvinism and Turkish trade". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2024-11-17.

- ^ "Kayseri Ulaşım A.Ş." Kayseri Ulaşım A.Ş. (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- ^ "2019–2020 Sezonu Kadın Ligleri Yönetim Kurulu Kararı – 2- Kadınlar 2. Ligi" (in Turkish). Türkiye Futbol Federasyonu. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ "TBMM Zabıt Ceridesi" (PDF). TBMM Tutanakları.

- ^ "Milli Mücadele Müzesi". www.kayseri.gov.tr. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "T.C. MİLLÎ EĞİTİM BAKANLIĞI KAYSERİ / KOCASİNAN / Nuh Mehmet Küçükçalık Anadolu Lisesi". nmkanadolulisesi.meb.k12.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "Tarihçemiz – TED KAYSERİ KOLEJİ". www.tedkayseri.k12.tr. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "ODTÜ Geliştirme Vakfı Okulları". www.odtugvo.k12.tr. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "AMERİKAN KOLEJİ VE HASTANESİ BİNASI". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "TALAS AMERİKAN KOLEJİ – TALAS'TA OKUYANLAR". Talas Amerikan Koleji. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "Abdullah Gul University – 3rd Generation State University". www.agu.edu.tr. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "Tarihçe". Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ "Tarihçe – Kayseri Tıp Fakültesi". kayseritip.sbu.edu.tr. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ "Aristotle Onassis". İzmir Life. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ "Kayseri'nin Kardeş Şehirleri". kayseriyerelhaber.com (in Turkish). Kayseri Yerel Haber. 2014-11-07. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Humus Kayseri". 2015-04-02. Archived from the original on 2016-12-27.

- ^ "Шуша и Кайсери станут городами–побратимами". interfax.az (in Russian). Interfax Azerbaijan. 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2021-07-29.