Bydgoszcz

Bydgoszcz | |

|---|---|

Downtown with Freedom Square Banks of the Brda River in the Old Town | |

| Nickname: | |

| Coordinates: 53°7′19″N 18°00′01″E / 53.12194°N 18.00028°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Kuyavian-Pomeranian |

| County | city county |

| Established | before 1238 |

| City rights | 1346 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Bydgoszcz City Council |

| • City mayor | Rafał Bruski (PO) |

| • City Council Chairperson | Monika Matowska (PO) |

| Area | |

• Total | 176 km2 (68 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2022) | |

• Total | 330,038 |

| • Density | 1,875/km2 (4,860/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | bydgoszczanin (male) bydgoszczanka (female) (pl) |

| GDP | |

| • Bydgoszcz–Toruń metropolitan area | €10.871 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 85-001 to 85–915 |

| Area code | (+48) 52 |

| Car plates | CB |

| Primary airport | Bydgoszcz Ignacy Jan Paderewski Airport |

| Highways | |

| Website | www |

Bydgoszcz[a] is a city in northern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Kuyavia. Straddling the confluence of the Vistula River and its left-bank tributary, the Brda, the strategic location of Bydgoszcz has made it an inland port and a vital centre for trade and transportation. With a city population of 339,053 as of December 2021,[5] Bydgoszcz is the eighth-largest city in Poland. Today, it is the seat of Bydgoszcz County and one of the two capitals of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship as a seat of its centrally appointed governor, a voivode.

Bydgoszcz metropolitan area comprising the city and several adjacent communities is inhabited by half a million people, and forms a part of an extended polycentric Bydgoszcz-Toruń metropolitan area with the population of approximately 0.8 million inhabitants. Since the Middle Ages, Bydgoszcz served as a royal city of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland until partitions and experienced the industrialisation period bolstered by the construction of the Bydgoszcz Canal in the late 18th century. Its academic and cultural landscape is shaped by Casimir the Great University, Bydgoszcz University of Science and Technology, the Medical College of Nicolaus Copernicus University, Feliks Nowowiejski Music Academy, the Pomeranian Philharmonic, and the Opera Nova. Bydgoszcz also plays a role of the biggest centre of NATO headquarters in Poland.[13][14] The city is served by an international airport and is a member of Eurocities.

Bydgoszcz is an architecturally rich city, with gothic, neo-gothic, neo-baroque, neoclassicist, modernist and Art Nouveau styles present, for which, combined with extensive green spaces, it has earned the nickname Little Berlin.[1] The notable granaries on Mill Island and along the riverside belong to one of the most recognized timber-framed landmarks in Poland.[15] In 2023, the city entered the UNESCO Creative Cities Network and was named UNESCO City of Music.[16]

Etymology

[edit]The name Bydgoszcz, originally Bydgoszcza, derives from Bydgost, a personal name, and the suffix -ja, denoting ownership. The German name Bromberg is an alteration of Braheberg, meaning "hill on the Brahe River" (Polish: Brda).[17] The Latin names for the city is Bidgostia and Civitas Bidgostiensis.

In Polish, the city's name has feminine grammatical gender.

History

[edit]Early history and first settlements

[edit]

In ancient times, there was a development of settlements related to lively trade contacts with the Roman Empire, as a convenient location of today's Bydgoszcz laid on the Amber Road heading northwest to the Baltic coastline avoiding crossing the Vistula river.[18][19][20]

During the early Slavic period a fishing settlement called Bydgoszcza ("Bydgostia" in Latin) became a stronghold on the Vistula trade routes.

The gród of Bydgoszcz was built between 1037 and 1053 during the reign of Casimir I the Restorer. In the 13th century it was the site of a castellany, mentioned in 1238, probably founded in the early 12th century during the reign of Bolesław III Wrymouth. In the 13th century, the church of Saint Giles was built as the first church of Bydgoszcz. The Germans later demolished it in the late 19th century.[21][better source needed] The first bridge was constructed at the reign of Casimir I of Kuyavia. In the early 14th century, the Duchy of Bydgoszcz and Wyszogród was created, with Bydgoszcz serving as its capital with Wyszogród, a settlement today within its borders.

During the Polish–Teutonic War (1326–1332), the city was captured and destroyed by the Teutonic Knights in 1330.[21][better source needed] Briefly regained by Poland, it was occupied by the Teutonic Knights from 1331 to 1337 and annexed to their monastic state as[citation needed][dubious – discuss] Bromberg. In 1337, it was recaptured by Poland and was relinquished by the Knights in 1343 at their signing of the Treaty of Kalisz along with Dobrzyń and the remainder of Kuyavia.

Royal city of Poland

[edit]King Casimir III of Poland granted Bydgoszcz city rights (charter) on 19 April 1346.[22] The king granted a number of privileges, regarding river trade on the Brda and Vistula and the right to mint coins, and ordered the construction of the castle, which became the seat of the castellan.[23] Bydgoszcz was an important royal city of Poland located in the Inowrocław Voivodeship.

The city increasingly saw an influx of Jews after that date.[citation needed] In 1555, however, due to pressure from the clergy, the Jews were expelled[citation needed] and returned only with their annexation to Prussia in 1772.[citation needed] After 1370, Bydgoszcz castle was the favourite residence of the grandson of the king and his would-be successor Duke Casimir IV, who died there in 1377.[23] In 1397 thanks to Queen Jadwiga of Poland, a Carmelite convent was established in the city, the third in Poland after Gdańsk and Kraków.[23]

During the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War in 1409 the city was briefly captured by the Teutonic Knights.[21] In the mid-15th century, during the Thirteen Years' War, King Casimir IV of Poland often stayed in Bydgoszcz. At that time, the defensive walls were built[21] and the Gothic parish church (the present-day Bydgoszcz Cathedral). The city was developing dynamically thanks to river trade. Bydgoszcz pottery and beer were popular throughout Poland. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Bydgoszcz was a significant location for wheat trading, one of the largest in Poland.[21][better source needed] The first mention of a school in Bydgoszcz is from 1466.[21][better source needed]

In 1480, a Bernardine monastery was established in Bydgoszcz.[23] The Bernardines erected a new Gothic church and founded a library, part of which has survived to this day.[23] A Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland was held in Bydgoszcz in 1520.[24] In 1522, after a decision taken by the Polish king, a salt depot was established in Bydgoszcz, the second in the region[which?] after Toruń.[21][better source needed] In 1594, Stanisław Cikowski founded a private mint, which in the early 17th century was transformed into a royal mint, one of the leading mints in Poland.[23]

In 1621, on the occasion of the Polish victory over the Ottoman Empire at Chocim, one of the most valuable and largest coins in the history of Europe was minted in Bydgoszcz – 100 ducats of Sigismund III Vasa.[23] In 1617 the Jesuits came to the city, and subsequently established a Jesuit college.[21][better source needed]

During the year of 1629, shortly before the end of the Polish-Swedish War of 1626–29, the town was conquered by Swedish troops led by king Gustav II Adolph of Sweden personally. During this war, the town suffered destruction.[25] The town was conquered a second and third time by Sweden in 1656 and 1657 during the Second Northern War. On the latter occasion, the castle was destroyed completely and has since remained a ruin. After the war only 94 houses were inhabited, 103 stood empty and 35 had burned down. The suburbs had also been considerably damaged.[26]

The Treaty of Bromberg, agreed in 1657 by King John II Casimir Vasa of Poland and Elector Frederick William II of Brandenburg-Prussia, created a military alliance between Poland and Prussia while marking the withdrawal of Prussia from its alliance with Sweden.

After the Convocation Sejm of 1764, Bydgoszcz became one of three seats of the Crown Tribunal for the Greater Poland Province of the Polish Crown alongside Poznań and Piotrków Trybunalski.[21][better source needed] In 1766 royal cartographer Franciszek Florian Czaki, during a meeting of the Committee of the Crown Treasury in Warsaw, proposed a plan of building a canal, which would connect the Vistula via the Brda with the Noteć river. Józef Wybicki, Polish jurist and political activist best known as the author of the lyrics of the national anthem of Poland, worked at the Crown Tribunal in Bydgoszcz.[27]

Late modern period

[edit]

In 1772, in the First Partition of Poland, the town was acquired by the Kingdom of Prussia as Bromberg and incorporated into the Netze District in the newly established province of West Prussia. At the time, the town was seriously depressed and semi-derelict.[28] Under Frederick the Great the town revived, notably with the construction of a canal from Bromberg to Nakel (Nakło) which connected the north-flowing Vistula River via the Brda to the west-flowing Noteć, which in turn flowed to the Oder via the Warta.[29] From this period until the end of the German Empire, a large majority of the city's inhabitants spoke German as their main language, and the city would later acquire the nickname "little Berlin" from its similar architectural appearance to the prewar image of the German capital and the work of shared architects such as Friedrich Adler, Ferdinand Lepcke, Heinrich Seeling, or Henry Gross.[4] During the Kościuszko Uprising, in 1794 the city was briefly recaptured by Poles, commanded by General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski,[23] and the local Polish administration was co-organized by Józef Wybicki.[27]

In 1807, after the defeat of Prussia by Napoleon and the signing of the Treaty of Tilsit, Bydgoszcz became part of the short-lived Polish Duchy of Warsaw, within which it was the seat of the Bydgoszcz Department. With Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Nations in 1813, the town was re-annexed by Prussia as part of the Grand Duchy of Posen (Poznań), becoming the capital of the Bromberg Region. During the November Uprising, a Polish insurgent organization was active in the city and local Poles helped smuggle volunteers, weapons and ammunition to the Russian Partition of Poland.[30] After the fall of the uprising, one of the main escape routes for surviving insurgents and civilian insurgent authorities from partitioned Poland to the Great Emigration led through the city.[31]

In 1871 the Province of Posen, along with the rest of the Kingdom of Prussia, became part of the newly formed German Empire. During German rule, the oldest church of the city (church of Saint Giles), the remains of the castle,[21][23] and the Carmelite church and monastery were demolished. In the mid-19th century, the city saw the arrival of the Prussian Eastern Railway. The first stretch, from Schneidemühl (Piła), was opened in July 1851.

At the time of World War I, Poles in Bydgoszcz formed secret organizations, preparing to regain control of the city in the event of Poland regaining its independence.[32]

Interbellum

[edit]

After the war, Bydgoszcz was assigned to the recreated Polish state by the 1919 Versailles Treaty. Now officially Bydgoszcz again, the city belonged to the Poznań Voivodeship. The local populace was required to acquire Polish citizenship or leave the country. This led to a drastic decline in ethnically German residents, whose number within the town decreased from over 40.000 in 1910 to 11,016 in 1926.[34] A Nazi German youth organization was subsequently founded, which distributed Nazi propaganda books from Germany among the German minority.[35]

The city's boundaries were greatly expanded in 1920 to include the surrounding suburbs of Okole, Szwederowo, Bartodzieje, Kapuściska, Wilczak, Jachcice and more, which made Bydgoszcz the third largest city in the Second Polish Republic[36] in terms of area. In 1938, the city was made part of the Polish Greater Pomerania.

World War II

[edit]

During the invasion of Poland, at the beginning of World War II, on September 1, 1939, Germany carried out air raids on the city. The Polish 15th Infantry Division, which was stationed in Bydgoszcz, fought off German attacks on September 2, but on September 3 was forced to retreat. During the withdrawal of Poles, as part of the diversion planned by Germany, local Germans opened fire on Polish soldiers and civilians. Polish soldiers and civilians were forced into a defensive battle in which several hundred people were killed on both sides. The event, referred to as the Bloody Sunday by the propaganda of Nazi Germany, which exaggerated the number of victims to 5,000 "defenceless" Germans, was used as an excuse to carry out dozens of mass executions of Polish residents in the Old Market Square and in the Valley of Death.[21][23] Between September 3–10, 1939, the Germans executed 192 Poles in the city.[37]

On September 5, while the Wehrmacht entered the city, German-Polish skirmishes still took place in the Szwederowo district, and the German occupation of the city began. The German Einsatzgruppe IV, Einsatzkommando 16 and SS-Totenkopf-Standarte "Brandenburg" entered the city to commit atrocities against the Polish population, and afterwards some of its members co-formed the local German police.[38] Many of the murders were carried out as part of the Intelligenzaktion, aimed at exterminating the Polish elites and preventing the establishment of a Polish resistance movement,[39] which emerged regardless. On September 24, the local German Kreisleiter called local Polish city officials to a supposed formal meeting in the city hall, from where they were taken to a nearby forest and exterminated.[40] The Kreisleiter also ordered the execution of their family members to "avoid creating martyrs".[40] By decision from September 5, 1939, one of the first three German special courts in occupied Poland was established in Bydgoszcz.[41]

The Germans established several camps and prisons for Poles.[37] As of September 30, 1939, over 3,000 individuals were imprisoned there, and in October and November, the Germans carried out further mass arrests of over 7,200 people.[42] Many of those people were then murdered.[43] Poles from Bydgoszcz were massacred at various locations in the city, at the Valley of Death and in the nearby village of Tryszczyn.[43] The victims were both men and women, including activists, school principals, teachers, priests, local officials, merchants, lawyers, and also boy and girl scouts, gymnasium students and children as young as 12.[44] The executions were presented as punishment for supposedly "murdering Germans" and "destroying peace", and were used by Nazi propaganda to show the world that it was alleged "Polish terror" that forced Hitler to start the war.[43] On the Polish National Independence Day, November 11, 1939, the Germans symbolically publicly executed Leon Barciszewski, the mayor of Bydgoszcz.[45] On November 17, 1939, the commander of the local SD-EK unit declared there was no more Polish intelligentsia capable of resistance in the city.[45]

The city was annexed to the newly formed province of Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia as the seat of the district or county (kreis) of Bromberg. However, the annexation was not recognised in international law. Extermination of the inhabitants continued throughout the war, and in total, around 10,000 inhabitants, mostly Poles, but also Polish Jews, were killed.[21][better source needed] Some Polish inhabitants were also murdered in the village of Jastrzębie in January 1940, and local teachers were also among Polish teachers murdered in both Mauthausen and Dachau concentration camps.[46] The history of Jews in Bydgoszcz ended with the German invasion of Poland and the Holocaust. The city's Jewish citizens, who constituted a small community in the city (about two percent of the prewar population)[47] and many of whom spoke German, were sent to extermination camps or murdered in the town itself. The city renamed Bromberg was the site of Bromberg-Ost, a women's subcamp of the Stutthof concentration camp. A deportation camp was situated in Smukała village, now part of Bydgoszcz. On February 4, 1941, the first mass transport of 524 Poles came to the Potulice concentration camp from Bydgoszcz.[48] The local train station was one of the locations, where Polish children aged 12 and over were sent from the Potulice concentration camp to slave labor.[49] The children reloaded freight trains.[49]

During the occupation, the Germans destroyed some of the city's historic buildings to erect new structures in the Nazi style.[23] The Germans built a huge secret dynamite factory (DAG Fabrik Bromberg) hidden in a forest in which they used the slave labor of several hundred forced laborers,[23] including Allied prisoners of war from the Stalag XX-A POW camp in Toruń.[50] In 1943, local Poles managed to save some kidnapped Polish children from the Zamość region, by buying them from the Germans at the local train station.[51]

The Polish resistance was active in Bydgoszcz. Activities included distribution of underground Polish press, sabotage actions, stealing German ammunition to aid Polish partisans, espionage of German activity[52] and providing shelter for British POWs who escaped from the Stalag XX-A POW camp.[53] The Gestapo cracked down on the Polish resistance several times.[54]

In spring 1945, Bydgoszcz was occupied by the advancing Red Army. Those German residents who had survived were expelled in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement and the city was returned to Poland, although with a Soviet-installed communist regime, which stayed in power until the 1980s. The Polish resistance remained active in Bydgoszcz.[55]

Post-war period

[edit]

In the same year 1945, the city was made the seat of the Pomeranian Voivodship, the northern part of which was soon separated to form Gdańsk Voivodship. The remaining part of the Pomeranian Voivodship was renamed Bydgoszcz Voivodeship in 1950. In 1951 and 1969, Bydgoszcz University of Science and Technology and Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz were founded respectively.

In 1973, the former town of Fordon, located on the left bank of the Vistula, was included in the city limits[47] and became the easternmost district of Bydgoszcz. In March 1981, Solidarity's activists were violently suppressed in Bydgoszcz.

With the Polish local government reforms of 1999, Bydgoszcz became the seat of the governor of a province entitled Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship. In 2005, Casimir the Great University was opened in Bydgoszcz.

Currently, Bydgoszcz is the biggest center of NATO headquarters in Poland, the most known being the Joint Force Training Centre. In May 2023, debris of a Russian Kh-55 air-sol missile was found in the forest of the near village Zamość.[56]

Main sights

[edit]The oldest building in the city is the Cathedral of St Martin and St Nicolas, commonly known as Fara Church. It is a three-aisle late Gothic church, erected between 1466 and 1502, which boasts a late-Gothic painting entitled Madonna with a Rose or the Holy Virgin of Beautiful Love from the 16th century. The colourful 20th-century polychrome is also especially worthy of note.

The Church of the Assumption of the Holy Virgin, commonly referred to as "The Church of Poor Clares," is a famous landmark of the city. It is a small, Gothic-Renaissance (including Neo-Renaissance additions), single-aisle church built between 1582 and 1602. The interior is rather austere since the church has been stripped of most of its furnishings. This is not a surprising fact, considering that in the 19th century the Prussian authorities dissolved the Order of St Clare and turned the church into a warehouse, among other uses. Nonetheless, the church is worth visiting. In particular, the original wooden polychrome ceiling dating from the 17th century draws the attention of every visitor.

Wyspa Młyńska (Mill Island) is among the most spectacular and atmospheric places in Bydgoszcz. What makes it unique is the location in the very heart of the city centre, just a few steps from the old Market Square. It was the 'industrial' centre of Bydgoszcz in the Middle Ages and for several hundred years thereafter, and it was here that the famous royal mint operated in the 17th century. Most of the buildings which can still be seen on the island date from the 19th century, but the so-called Biały Spichlerz (the White Granary) recalls the end of the 18th century. However, it is the water, footbridges, historic red-brick tenement houses reflected in the rivers, and the greenery, including old chestnut trees, that create the unique atmosphere of the island.

"Hotel pod Orłem" (The Eagle Hotel), an icon of the city's 19th-century architecture, was designed by the distinguished Bydgoszcz architect Józef Święcicki, the author of around sixty buildings in the city. Completed in 1896, it served as a hotel from the very beginning and was originally owned by Emil Bernhardt, a hotel manager educated in Switzerland. Its façade displays forms characteristic of the Neo-baroque style in architecture.

Saint Vincent de Paul's Basilica, erected between 1925 and 1939, is the largest church in Bydgoszcz and one of the biggest in Poland. It can accommodate around 12,000 people. This monumental church, modeled after the Pantheon in Rome, was designed by the Polish architect Adam Ballenstaedt. The most characteristic element of the neo-classical temple is the reinforced concrete dome 40 metres in diameter.

The three granaries in Grodzka Street, picturesquely located on the Brda River near the old Market Square, are the official symbol of the city. Built at the turn of the 19th century, they were originally used to store grain and similar products, but now house exhibitions of the city's Leon Wyczółkowski District Museum.

The building of the former Prussian Eastern Railway Headquarters erected between 1886 and 1889 in Dutch Mannierist style is another notable structure in the city. Initially it served as a headquarters of the Prussian Eastern Railway and later it belonged to the Polish State Railways. Since 2022 it is privately owned.

The city is mostly associated with water, sports, Art Nouveau buildings, waterfront, music, and urban greenery. Bydgoszcz boasts the largest city park in Poland (830 ha). The city was also once famous for its industry.

Some great monuments have been destroyed, for example, the church in the Old Market Square and the Municipal Theatre. Additionally, the Old Town lost a few characteristic tenement houses, including the western frontage of the Market Square. The city also lost its Gothic castle and defensive walls. In Bydgoszcz, there are a great number of villas in the style of typical garden suburbs.

Economy and demographics

[edit]

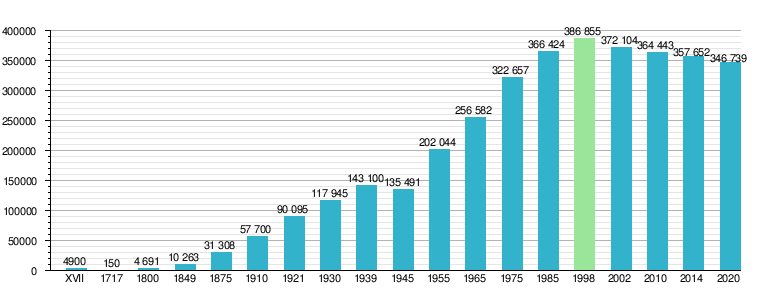

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 162,524 | — |

| 1960 | 232,007 | +42.8% |

| 1970 | 282,200 | +21.6% |

| 1978 | 338,014 | +19.8% |

| 1988 | 377,807 | +11.8% |

| 2002 | 373,804 | −1.1% |

| 2011 | 363,926 | −2.6% |

| 2021 | 337,666 | −7.2% |

| Source: [57][58][59][60][61] | ||

In the city, there are 38 banks represented through a network of 116 branches (including the headquarters of the Bank Pocztowy SA), whilst 37 insurance companies also have offices in the city. JP Morgan Chase, one of the largest financial institutions in the world, has established a branch in Bydgoszcz. Most industrial complexes are scattered throughout the city. Of note are the 'Zachem' chemical works, covering dozens of square kilometers in the south-east of the city. These remnants of the German explosives factory built in World War II occupy an area which has its own rail lines, internal communication and housing, plus a large forested area. An open-air museum, the Exploseum, is located here as well.

Since 2001, Bydgoszcz has been annually subjected to international 'verification' ratings. In February 2008 the 'Fitch Ratings' Agency recategorised the city, increasing its rating from BBB-(stable forecast) to BBB (stable estimate).

In 2004, Bydgoszcz launched an Industrial and Technology Park of 283 hectares, an attractive place for doing business as companies that relocate there receive tax breaks, 24-hour security, access to large plots of land and to the media, the railway line Chorzów Batory – Tczew (passenger, coal), the DK5 and DK10 national roads, and future freeways S10 and S5. Bydgoszcz Airport is also close by.

Population growth since 17th century

[edit]

Culture

[edit]

Bydgoszcz is a major cultural centre in the country, especially for music. Traditions of the municipal theatre date back to the 17th century, when the Jesuit college built a theatre. In 1824, a permanent theatre building was erected, and this was rebuilt in 1895 in a monumental form by the Berlin architect Heinrich Seeling. The first music school was established in Bydgoszcz in 1904; it had close links to the very well-known European piano factory of Bruno Sommerfeld. Numerous orchestras and choirs, both German (Gesangverein, Liedertafel) and Polish (St. Wojciech Halka, Moniuszko), have also made the city their home. Since 1974, Bydgoszcz has been home to a very prestigious Academy of Music. Bydgoszcz is also an important place for contemporary European culture; one of the most important European centers of jazz music, the Brain club, was founded in Bydgoszcz by Jacek Majewski and Slawomir Janicki.

Bydgoszcz was a candidate for the title of European Capital of Culture in 2016. [62] It joined the list of UNESCO's Cities of Music in 2023.[63]

Museums

[edit]

Muzeum Okręgowe im. Leona Wyczółkowskiego (Leon Wyczółkowski District Museum) is a municipally-owned museum. Apart from a large collection of Leon Wyczółkowski's works, it houses permanent as well as temporary exhibitions of art. It is based in several buildings, including the old granaries on the Brda River and Mill Island and the remaining building of the Polish royal mint. Exploseum, a museum built around the World War II Nazi Germany munitions factory, is also part of it.

In Bydgoszcz, the Pomeranian Military Museum specializes in documenting 19th- and 20th-century Polish military history, particularly the history of the Pomeranian Military District and several other units present in the area.

The city has many art galleries, two symphony orchestras, many chamber orchestras and choirs. Bydgoszcz's cultural facilities also include libraries, including the Provincial and Municipal Public Library with an extensive collection of volumes from the 15th to the 19th centuries. The municipally-owned Palaces and park ensemble in Ostromecko near the city contains the Andrzej Szwalbe Collection of Historical Pianos, one of the largest such collections in Poland.

Classical music

[edit]

- The Pomeranian Philharmonic performance home with full name Filharmonia Pomorska im. Ignacego Paderewskiego (Ignacy Paderewski's [Concert Hall]) includes its 880-seat main hall, the Arthur Rubinstein Hall, a key European, rectangular, concert hall with superb acoustic qualities, still mainly hosting all types of classical music.

Popular music

[edit]- Concerts of popular music in Bydgoszcz are usually held in Filharmonia Pomorska, Łuczniczka, Zawisza and Polonia stadiums as well as open plains of Myslecinek's Rozopole on the outskirts of the city.

- Alternative music festival "Low Fi" [1] Archived 2015-11-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Smooth Festival Złote Przeboje Bydgoszcz

- Eska Music Festival Bydgoszcz

- Hity na Czasie Festival Bydgoszcz

- Bydgoszcz Hit Festival

Theatre

[edit]

Teatr Polski im Hieronima Konieczki (Hieronim Konieczka's Polish Theatre): Despite its name, the theatre offers a wide variety of shows both of national and foreign origin. It also regularly plays host to a large number of touring shows. Founded in 1949, since 2002 the theatre has taken part in the "Festiwal Prapremier" where the most renowned Polish theatres stage their latest works. There are also a number of private theatre companies operating in Bydgoszcz.

From 1960 to 1986, there was an outdoor theater, the reactivation of which is currently being pursued by the Theatre Culture Association, "Fides" and the Acting School A. Grzymala-Siedlecki.

The Pomeranian Philharmonic named after Ignacy Jan Paderewski has existed since 1953. The concert hall, which can hold 920 people is classified, in terms of sound, as one of the best in Europe, which is confirmed by well-known artists and critics (including Jerzy Waldorff). Due to the phenomenon of acoustics, it attracts the interest of many famous artists. Bydgoszcz's stage has been frequented by many global celebrities, including Arthur Rubinstein, Benjamin Britten, Witold Małcużyński, Luciano Pavarotti, Shlomo Mintz, Mischa Maisky, Kevin Kenner, Kurt Masur, Kazimierz Kord, Jerzy Maksymiuk and Antoni Wit. In recent years, the city has also hosted an excellent range of bands such as the BBC Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, and others.

The Opera Nova, in existence since 1956, started the construction of a new building in 1974 which was to consist of three main halls, situated on the Brda. The Opera Nova has become a cultural showcase of Bydgoszcz in the world. Considering the short history of the Opera, its success has been astounding; a large number of famous opera singers have performed there and theatrical troops from the Wrocław Opera, Theatre of Leningrad, Moscow, Kiev, Minsk, and Gulbenkian Foundation of Lisbon have also made appearances.

Cinematography

[edit]- The International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography CAMERIMAGE is a festival dedicated to cinematography and its creators cinematographers.

Education

[edit]

|

|

|

Transport

[edit]Airports

[edit]Railways

[edit]Bydgoszcz is one of the biggest railway junctions in Poland, with two important lines crossing there – the east–west connection from Toruń to Pila and the north–south line from Inowrocław to Gdańsk (see: Polish Coal Trunk-Line). There are also secondary-importance lines stemming from the city, to Szubin and to Chełmża. Among rail stations located in the city, there are:

|

|

Buses and trams

[edit]- Local buses and trams are operated by Zarząd Dróg Miejskich i Komunikacji Publicznej w Bydgoszczy

- PKS Bydgoszcz – operates inter-city and international bus routes.

-

Historic main railway station in Bydgoszcz

-

Modern part of the main railway station

-

Tram in Bydgoszcz

Sports

[edit]

Sports clubs

[edit]- Basket 25 Bydgoszcz – women's basketball team playing in Basket Liga Kobiet, the country's top division.

- Astoria Bydgoszcz – men's basketball team playing in Polish Basketball League, the country's top division (as of 2022–23).

- Bydgoszcz Archers – American football team playing in Polish Football League, the country's top division.

- Pałac Bydgoszcz – women's volleyball team playing in Polish Women's Volleyball League, the country's top division.

- BKS Visła Bydgoszcz – men's volleyball team playing in Polish Volleyball League, the country's top division.

- KKP Bydgoszcz – women's football team playing in Ekstraliga, the country's top division.

- Chemik Bydgoszcz – men's football team playing in the country's lower league.

- Polonia Bydgoszcz – speedway team, seven-time Polish League champions (lately in 2002) and three-time European Speedway Club Champions' (lately in 2001) and football team, which played in the top tier in the 1950s and 1960s.

- Zawisza Bydgoszcz – football team, which played in the past in the country's top flight, most recently in 2015, currently playing in the lower league.

- RTW Bydgostia Bydgoszcz – Rowing (sport) Bydgostia Regional Rowing Association was founded on 4 December 1928. The club was A Team Polish Champion in the following years: 1938, 1966, 1967, 1970 and for the successive seventeen years from 1993 to 2009.

- Gwiazda Bydgoszcz – men's table tennis team playing in Superliga, the country's top division. The club is also successfully competing in table tennis Europe Cup.

Sports facilities

[edit]- Łuczniczka, Show and Fair Arena

- Sisu Arena, a closed indoor arena

- Zdzisław Krzyszkowiak Stadium

- Polonia Stadium

- Hala Torbyd, a closed indoor arena

Sports events

[edit]- Athletics

- 2003 European Athletics U23 Championships

- 2008 World Junior Championships in Athletics

- 2010 IAAF World Cross Country Championships

- 2013 IAAF World Cross Country Championships

- 2016 World Junior Championships in Athletics

- 2017 European Athletics U23 Championships

- 2019 European Team Championships

- European Athletics Festival Bydgoszcz (annual event part of the European Permit Meetings circuit)

- Speedway

- Grand Prix of Poland: (1998–1999, 2001–2009)

- Grand Prix of Europe: (2000)

- Mieczysław Połukard Criterium of Polish Speedway Leagues Aces (1951–1960, since 1982)

- Team sports

Politics

[edit]Bydgoszcz constituency

[edit]Members of Polish Sejm 2007–2011 elected from Bydgoszcz constituency:

|

|

|

Members of Polish Senate 2007–2011 elected from Bydgoszcz constituency:

- Zbigniew Pawłowicz, Civic Platform

- Jan Rulewski, Civic Platform

International relations

[edit]Consulates

[edit]There is an Honorary Consulate General of Hungary in Bydgoszcz, and nine honorary consulates, of Austria,[65] Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany, Montenegro,[66] Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine.[67]

Twin towns and friendship relations

[edit]

| Twin Towns | ||

| City/Town | Country | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Reggio Emilia | 12.04.1962 | |

| Kragujevac[68] | 23.07.1971 | |

| Mannheim[69] | 26.11.1991 | |

| Hartford | 30.09.1996 | |

| Pavlodar | 10.04.1997 | |

| Perth | 9.05.1998 | |

| Cherkasy | 13.09.2000 | |

| Kremenchuk | 30.06.2004 | |

| Patras | 8.10.2004[71] | |

| Ningbo | 28.12.2005 | |

| Wilhelmshaven | 19.04.2006 | |

| Pitești | 22.06.2007[72][73] | |

| Sliven | 9.09.2019 | |

Legends

[edit]It is said that Pan Twardowski spent some time in the city of Bydgoszcz, where, in his memory, a figure was recently mounted in a window of a tenement, overseeing the Old Town. At 1:13 p.m. and 9:13 p.m. the window opens and Pan Twardowski appears, to the accompaniment of weird music and devilish laughter. He takes a bow, waves his hand, and then disappears. This little show gathers crowds of amused spectators.

Gallery

[edit]-

Main Library on the Old Market Square

-

Ralph Modjeski Bridge in Fordon District

-

Former headquarters of the

Prussian Eastern Railway -

Former Jesuit College (1617), now City Hall

-

Bydgoszcz Cathedral's façade

-

Bydgoszcz Scientific Society

-

Birthplace of Marian Rejewski

-

Brda River in the city centre

-

Former Polish Royal mint, now a museum

-

Sluice gate on Bydgoszcz Canal

-

The district court building

-

Czerwony Spichlerz - Museum of Contemporary Art in Bydgoszcz

-

School of Fine Arts

-

Music Club Eljazz

-

Nordic Haven apartment block

-

Bernardine church

-

The University Bridge

-

Statue of John of Nepomuk

-

The White Granary, seat of the Archeological Museum in Bydgoszcz

-

Łuczniczka (The Archeress)

Climate

[edit]Bydgoszcz has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb).

| Climate data for Bydgoszcz (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–1982 and 1992–2015) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

22.8 (73.0) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.9 (89.4) |

35.5 (95.9) |

38.3 (100.9) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.4 (92.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

38.3 (100.9) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

15.7 (60.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

2.7 (36.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.5 (36.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

8.5 (47.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.7 (25.3) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −14.9 (5.2) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

0.9 (33.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −29.9 (−21.8) |

−26.6 (−15.9) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34.3 (1.35) |

26.3 (1.04) |

36.4 (1.43) |

28.2 (1.11) |

52.8 (2.08) |

56.7 (2.23) |

83.4 (3.28) |

55.6 (2.19) |

48.0 (1.89) |

40.1 (1.58) |

33.6 (1.32) |

36.9 (1.45) |

532.3 (20.95) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 16.0 | 13.4 | 12.9 | 10.5 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 12.0 | 10.9 | 12.7 | 13.7 | 16.9 | 158.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86.8 | 86.6 | 81.4 | 71.5 | 69.7 | 71.1 | 73.6 | 75.4 | 81.7 | 86.3 | 90.5 | 89.3 | 80.3 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −4 (25) |

−3 (27) |

−1 (30) |

2 (36) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

13 (55) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

6 (43) |

3 (37) |

−1 (30) |

5 (40) |

| Source 1: Meteomodel.pl[74][75] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Time and Date (dewpoints, 2005-2015)[76] | |||||||||||||

People born in Bydgoszcz

[edit]

|

|

|

See also

[edit]- Bydgoszcz dialect (Gwara bydgoska, Bromberger Dialekt)

- Bydgoszcz Architects (1850-1970s)

- Gdańska Street

- Dworcowa Street

- Theatre square

- Mill Island

- Freedom Square

- Grodzka Street

- Nakielska street

- Cieszkowskiego Street

- Independence Estate (Bydgoszcz)

- Jagiellońska street

- Stary Port Street

- Bernardyńska Street

- Podwale Street

- Długa street

- Adam Mickiewicz Alley

- Ossoliński Alley

- Śniadeckich Street

- Pomorska Street

- Focha Street

- Krasińskiego Street

- Bydgoszcz Synagogue, former synagogue in the city

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Bydgoszcz

- Piastowski Square

- Konarskiego Street

- Piotra Skargi Street

- Kołłątaja street in Bydgoszcz

- Gimnazjalna, Libelta and Szwalbego Streets

- Mikołaja Reja Street

- Swiętej Trojcy street

- Kopernika Street

- Krakowska Street

- Osowa Góra

- Flisy (Bydgoszcz district)

- Glinki (Bydgoszcz district)

- Freedom Hill

Notes

[edit]- ^

- Pronunciation:

- British English: /ˈbɪdɡɒʃtʃ/ BID-goshtch[7]

- American English: US: /-ɡɔːʃ(tʃ)/ -gawsh(tch)[8][9][10]

- Polish: Polish pronunciation: [ˈbɨdɡɔʂt͡ʂ]

- German: Bromberg, pronounced [ˈbʁɔmˌbɛʁk]

- Latin: Bidgostia/Bydgostia,[11] Brombergum[12]

- Yiddish: בידגאש, romanized: Bidgash

- Pronunciation:

References

[edit]- ^ a b Team, 3W Design. "Camerimage – International Film Festival". www.camerimage.pl. Archived from the original on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bydgoszcz as "Klein Berlin"". visitbydgoszcz.pl. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "ul. Cieszkowskiego, Bydgoszcz". inyourpocket.com. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Berlin i "klein Berlin" na jednej pocztówce. Dzieła tych samych architektów w Niemczech i Bydgoszczy". wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 2022-06-02. Data for territorial unit 0461011.

- ^ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by NUTS 3 regions". ec.europa.eu.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Wiesław Wydra, Chrestomatia staropolska. Teksty do roku 1543. Wrocław. Ossolineum. 1984. ISBN 83-04-01568-4.

- ^ Brombergum attested e.g. in: [Anon.]: Geographica Globi Terraquei Synopsis [...]. Trnava 1745, p. 278; Laur. Mizlerus de Kolof: Historiarum Poloniae et Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae Scriptorum [...] Collectio Magna [...]. Vol. 2. Warsaw 1769, p. 456; Fran. Math. Stan. Val. Hoefft: De Sanguinis Transfusione. Ph.D. thesis, Berlin 1819, p. 47.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz - Polska stolica NATO". miasta.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz umacnia swą pozycję w strukturach NATO". bydgoszcz.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Granaries on the Brda – Bydgoszcz, Official Tourism Website, visitbydgoszcz.pl". www.visitbydgoszcz.pl. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "55 new cities join the UNESCO Creative Cities Network on World Cities Day". unesco.org. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Niemeyer, Manfred, ed. (2012). Deutsches Ortsnamenbuch. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 94. ISBN 978-3-11-025802-8.

- ^ Ptolemy (150). "Photo Gallery: Ptolemy's Geography". The Mirror - International. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Dygaszewicz, Elżbieta (2000). "From Paleolithic to the Middle Ages". Bydgoszcz Calendar. Bydgoszcz: Society for the Lovers of Bydgoszcz City. ISSN 0209-3081. OCLC 1150533527.

- ^ *Wilke, Gerard (1991–2015). "Prehistory and Early Middle Ages in the Light of Archaeological Sources (until the Beginning of the 12th Century)". In Biskup, Marian; Naukowe, Bydgoskie Towarzystwo (eds.). History of Bydgoszcz. Vol. I. Warsaw: State Publishing House, Sciences. ISBN 8301066660. OCLC 27641385.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Historia Bydgoszczy". Bydgoski Serwis Turystyczny (in Polish). Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Heinrich Gottfried Philipp Gengler: Regesten und Urkunden zur Verfassungs- und Rechtsgeschichte der deutschen Städte im Mittelalter. Volume I, Enke, Erlangen 1863, pp. 403–404 and pp. 976–977.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Historia Bydgoszczy". VisitBydgoszcz.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Konopczyński, Władysław (1948). Chronologia sejmów polskich 1493–1793 (in Polish). Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności. p. 135.

- ^ Ludwig Kühnast: Historische Nachrichten über die Stadt Bromberg – Von der Gründung der Stadt bis zur preußischen Besitznahme. Bromberg Berlin Posen 1837, pp 64–68.

- ^ Ludwig Kühnast (1837), pp. 112–117.

- ^ a b Krzysztof Drozdowski. "Rocznica śmierci Józefa Wybickiego. Razem z generałem Dąbrowskim wyzwalał Bydgoszcz". Tygodnik Bydgoski (in Polish). Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ August Eduard Preuß: Preußische Landes- und Volkskunde. Königsberg 1835, p. 381.

- ^ Baedeker, Karl, Northern Germany, London, 1904, p.163.

- ^ Umiński, Janusz (1998). "Losy internowanych na Pomorzu żołnierzy powstania listopadowego". Jantarowe Szlaki (in Polish). Vol. 4, no. 250. p. 13.

- ^ Umiński, p. 16

- ^ Stefan Pastuszewski. "Bydgoszcz w ręce polskie przeszła pokojowo". Tygodnik Bydgoski (in Polish). Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Bydgoszcz niepodległa. Kadry, przedmioty i gmachy XX-lecia". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Kotowski, Albert S. (1998). Polens Politik gegenüber seiner deutschen Minderheit 1919–1939 (in German). Forschungsstelle Ostmitteleuropa, University of Dortmund. p. 56. ISBN 3-447-03997-3.

- ^ Wardzyńska 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Infrastruktura i gospodarka komunalna. Historia Bydgoszczy. Tom II. Część druga 1920-1939: red. Marian Biskup: Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe 2004. s. 233–249, ISBN 83-921454-0-2

- ^ a b Wardzyńska 2009, p. 110.

- ^ Wardzyńska 2009, pp. 55, 61–62.

- ^ Wardzyńska 2009, p. 71.

- ^ a b Wardzyńska 2009, p. 102.

- ^ Grabowski, Waldemar (2009). "Polacy na ziemiach II RP włączonych do III Rzeszy". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). No. 8–9 (103–104). IPN. p. 62. ISSN 1641-9561.

- ^ Wardzyńska 2009, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b c Wardzyńska 2009, p. 158.

- ^ Wardzyńska 2009, pp. 158–160.

- ^ a b Wardzyńska 2009, p. 160.

- ^ Wardzyńska 2009, pp. 180–182.

- ^ a b "Encyklopedia PWN". Encyklopedia.pwn.pl. Archived from the original on March 24, 2005. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Molesztak, Aldona (2020). "Doświadczenia obozowe dzieci w niemieckim obozie przesiedleńczym i pracy w Potulicach i Smukale - wspomnienia więźniarek". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in Polish). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. p. 193.

- ^ a b Paczoska, Alicja (2003). "Dzieci Potulic". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). No. 12–1 (35–36). IPN. p. 61. ISSN 1641-9561.

- ^ Bukowska, Hanna (2013). "Obóz jeniecki Stalag XXA w Toruniu 1939-1945". Rocznik Toruński (in Polish). Vol. 40. Towarzystwo Miłośników Torunia, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika. p. 107. ISSN 0557-2177.

- ^ Kozaczyńska, Beata (2020). "Gdy zabrakło łez... Tragizm losu polskich dzieci wysiedlonych z Zamojszczyzny (1942-1943)". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in Polish). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. p. 123.

- ^ Chrzanowski 2022, pp. 30, 40–41, 47–48, 57, 62.

- ^ Chrzanowski, Bogdan. "Organizacja sieci przerzutów drogą morską z Polski do Szwecji w latach okupacji hitlerowskiej (1939–1945)". Stutthof. Zeszyty Muzeum (in Polish). 5: 30, 33–34. ISSN 0137-5377.

- ^ Chrzanowski 2022, p. 39.

- ^ Chrzanowski 2022, p. 74.

- ^ "Military object found in Polish forest was Russian missile - media". Reuters. 2023-05-10. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ^ "1950 census" (PDF).

- ^ "1960 census" (PDF).

- ^ "1970 census" (PDF).

- ^ "Demographic and occupational structure and housing conditions of the urban population in 1978-1988" (PDF).

- ^ "Statistics Poland - National Censuses".

- ^ City of Bydgoszcz Municipal website

- ^ "55 new cities join the UNESCO Creative Cities Network on World Cities Day". Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ WSB University in Toruń Archived 2016-03-01 at the Wayback Machine – WSB Universities

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20180418092912/http://www2.um.bydgoszcz.pl/miasto/wspolpraca_z_zagranica/Konsulaty_Honorowe_w_Bydgoszczy.aspx

- ^ https://www.bydgoszcz.pl/promocja/wspolpraca-z-zagranica/konsulaty-honorowe-w-bydgoszczy/konsulat-honorowy-czarnogory-w-bydgoszczy/

- ^ "Misje dyplomatyczne, urzędy konsularne i organizacje międzynarodowe w Polsce". Portal Gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Kragujevac Twin Cities". ©2009 Information service of Kragujevac City. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- ^ "Partner und Freundesstädte". Stadt Mannheim (in German). Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ^ "Miasta partnerskie". City of Bydgoszcz (in Polish). 18 October 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

Perth, Szkocja

- ^ "Διεθνείς Σχέσεις". e-patras.gr. Archived from the original on 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ "Twinning Agreement". Bydgoszcz City Hall. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "Pitesti (Rumania)" (in Polish). Oficjalny Serwis Bydgoszczy. 6 October 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "Średnie i sumy miesięczne" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Średnie i sumy miesięczne" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in Bydgoszcz". Time and Date. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

External links

[edit]- Bydgoszcz.pl homepage (Polish)

- Visit Bydgoszcz.pl homepage (Polish, English)

- Municipal website (in English)

Bibliography

[edit]- Chrzanowski, Bogdan (2022). Polskie Państwo Podziemne na Pomorzu w latach 1939–1945 (in Polish). Gdańsk: IPN. ISBN 978-83-8229-411-8.

- Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN.

Further reading

[edit]- Ludwig Kühnast: Historische Nachrichten über die Stadt Bromberg – Von der Gründung der Stadt bis zur preußischen Besitznahme (Historical news about the town of Bromberg – From the town's founding to the Prussian occupation). Bromberg Berlin Posen 1837 (Online) (in German).