Burning bush

The burning bush (or the unburnt bush) refers to an event recorded in the Jewish Torah (as also in the biblical Old Testament and Islamic scripture). It is described in the third chapter of the Book of Exodus[1] as having occurred on Mount Horeb. According to the biblical account, the bush was on fire but was not consumed by the flames, hence the name.[2] In the biblical and Quranic narrative, the burning bush is the location at which Moses was appointed by God to lead the Israelites out of Egypt and into Canaan.

The Hebrew word in the narrative that is translated into English as bush is seneh (Hebrew: סְנֶה, romanized: səne), which refers in particular to brambles;[3][4][5] seneh is a dis legomenon, only appearing in two places, both of which describe the burning bush.[4] The use of seneh may be a deliberate pun on Sinai (סיני), a feature common in Hebrew texts.[6]

Biblical narrative

[edit]In the narrative, an angel of the Lord is described as appearing in a bush[7] and God is subsequently described as calling out from it to Moses, who had been grazing Jethro's flocks there.[2] When Moses starts to approach, God tells Moses to take off his sandals first due to the place being a sacred space.[8]

The voice from the bush, which later self-discloses as Yahweh, reveals himself as "the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob"[9] and thus Moses hides his face.[9]

Some Old Testament scholars regard the account of the burning bush as being spliced together from the Yahwist and Elohist texts, with the angel of Yahweh and the removal of sandals being part of the Yahwist version, and the Elohist's parallels to these being God and the turning away of Moses's face, respectively.[6][10][5]

The text portrays Yahweh as telling Moses that he is sending him to Pharaoh to bring the Israelites out of Egypt, an action that Yahweh decided upon as a result of noticing that the Israelites were being oppressed by the Egyptians.[11] Yahweh tells Moses to tell the elders of the Israelites that Yahweh would lead them into the land of the Canaanites, Hittites, Amorites, Hivites, and Jebusites,[12] a region generally referred to as a whole by the term Canaan; this is described as being a land of "milk and honey".[12]

Moses asks "When I come to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is His name?’ what shall I say to them?” (Ex 3:13) The voice of God from the bush reveals that he is Yahweh.[13] The text derives Yahweh (יהוה) from the Hebrew word היה ([haˈja]) in the phrase אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה "I Am Who I Am".[5]

According to the narrative, Yahweh instructs Moses to confront the Egyptians and Israelites and briefs the prophet on what is to take place. Yahweh then performs various demonstrative miracles in order to bolster Moses's credibility. Among other things, his staff was transmuted into a snake,[14] Moses's hand was temporarily afflicted with "snowy tzaraath",[15] and water was transmuted into blood.[16] In the text, Yahweh instructs Moses to take a staff in his hands to perform miracles with it,[16] as if it is a staff given to him rather than his own;[5] some textual scholars propose that this latter instruction is the Elohist's version of the more detailed earlier description, where Moses uses his staff, which they attribute to the Yahwist.[10][5]

Despite the signs, Moses is described as being very reluctant to take on the role, arguing that he lacked eloquence and that someone else should be sent instead;[17] in the text, Yahweh reacts by angrily rebuking Moses for presuming to lecture the one who made the mouth on who was qualified to speak and not to speak. Yet Yahweh concedes and allows Aaron to be sent to assist Moses since Aaron is eloquent and already on his way to meet Moses.[18] This is the first time in the Torah that Aaron is mentioned and he is described as being Moses's mouthpiece.[19]

Alternative theories

[edit]Alexander and Zhenia Fleisher relate the biblical story of the burning bush to the plant Dictamnus.[20] They write:

Intermittently, under yet unclear conditions, the plant excretes such a vast amount of volatiles that lighting a match near the flowers and seedpods causes the plant to be enveloped by flame. This flame quickly extinguishes without injury to the plant.

They conclude, however, that Dictamnus spp. are not found in the Sinai peninsula, adding: "It is, therefore, highly improbable that any Dictamnus spp. was a true 'Burning Bush', despite such an attractive rational foundation."

Colin Humphreys replies that "the book of Exodus suggests a long-lasting fire that Moses went to investigate, not a fire that flares up and then rapidly goes out."[21]

Another theory is that it is sunlight on Har Karkom reflected in a surprising way to appear like fire.[22]

Location

[edit]

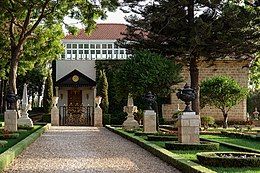

Christian hermits originally gathered at Mount Serbal, believing it to be the biblical Mount Sinai. However, in the 4th century, under the Byzantine Empire, the monastery built there was abandoned in favour of the newer belief that Mount Saint Catherine was the Biblical Mount Sinai; a new monastery – Saint Catherine's Monastery – was built at its foot, and the alleged site of the biblical burning bush was identified. The bush growing at the spot (a bramble, scientific name Rubus sanctus),[23] was later transplanted several yards away to a courtyard of the monastery, and its original spot was covered by a chapel dedicated to the Annunciation, with a silver star marking where the roots of the bush had come out of the ground. The Monks at Saint Catherine's Monastery, following church tradition, believe that this bush is, in fact, the original bush seen by Moses, rather than a later replacement,[citation needed] and anyone entering the chapel is required to remove their shoes, just as Moses was said to have done so in the biblical account.

However, in modern times, it is not Mount Saint Catherine, but the adjacent Jebel Musa (Mount Moses), which is currently identified as Mount Sinai by popular tradition and guidebooks; this identification arose from Bedouin tradition.

Mount Serbal, Mount Sinai, and Mount Saint Catherine all lie at the southern tip of the Sinai peninsula, but the peninsula's name is a comparatively modern invention. It was not known by that name at the time of Josephus or earlier. Some modern scholars and theologians, favor locations in the Hijaz (at the north west of Saudi Arabia), northern Arabah (in the vicinity of Petra, or the surrounding area), or occasionally in the central or northern Sinai Peninsula. Hence, the majority of academics and theologians agree that if the Burning Bush ever existed, then it is highly unlikely to be the bush preserved at St Catherine's Monastery.

Symbolism and interpretations

[edit]Judaism

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2024) |

The logo of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America is also an image of the burning bush with the phrase "and the bush was not consumed" in both English and Hebrew.[24]

The Zohar, a late 1200s work of Kabbalah, suggests the burning bush was a hint that even though the Israelites were suffering in Egypt, they had God's protection, like the bush that was burning but not consumed.[25]

Christianity

[edit]

Catholic church

[edit]In the medieval Catholic church the event was seen as a typological parallel for the Virgin Birth of Jesus from Mary, who conceived as a virgin, as the bush was burnt but not destroyed. Depictions in medieval Catholic art, such as the 15th-century Burning Bush Triptych altarpiece, therefore typically show a Virgin and Child in the middle of the bush or tree. The inscription on the base of the frame which translates (from Latin) as "In the bush which Moses saw burning without being consumed, we recognised, Holy Mother of God, your virginity wondrously preserved". The Eastern Orthodox view was similar.

Eastern Orthodoxy

[edit]

In Eastern Orthodoxy a tradition exists, originating in the early Christian Church Fathers and its Ecumenical Synods (or Councils), that the flame Moses saw was in fact God's Uncreated Energies/Glory, manifested as light, thus explaining why the bush was not consumed. It is viewed as Moses being permitted to see these Uncreated Energies/Glory, which are considered to be eternal things; the Orthodox definition of salvation is this vision of the Uncreated Energies/Glory, and it is a recurring theme in the works of Greek Orthodox theologians such as John S. Romanides.

In Eastern Orthodox parlance, the preferred name for the event is The Unburnt Bush, and the theology and hymnography of the church view it as prefiguring the virgin birth of Jesus; Eastern Orthodox theology refers to Mary, the mother of Jesus as the Theotokos ("God bearer"), viewing her as having given birth to Incarnate God without suffering any harm, or loss of virginity, in parallel to the bush being burnt without being consumed.[27] There is an icon-type by the name of the Unburnt Bush, which portrays Mary in the guise of God bearer; the icon's feast day is held on 4 September (Russian: Неопалимая Купина, romanized: Neopalimaya Kupina).

While God speaks to Moses, in the narrative, Eastern Orthodoxy believes that the angel was also heard by Moses; Eastern orthodoxy interprets the angel as being the Logos of God,[citation needed] regarding it as the Angel of Great Counsel mentioned in the Septuagint version of Isaiah 9:6;[28] (it is Counsellor, Mighty God in the Masoretic Text).

Reformed tradition

[edit]The burning bush has been a popular symbol among Reformed churches since it was first adopted by the Huguenots (French Calvinists) in 1583 during its 12th National Synod. The French motto Flagror non consumor – "I am burned but not consumed" – suggests the symbolism was understood of the suffering church that nevertheless lives.[29] However, given the fire is a sign of God's presence, he who is a consuming fire (Hebrews 12:29) the miracle appears to point to a greater miracle: God, in grace, is with his covenant people and so they are not consumed.

- The current symbol of the Reformed Church of France is a burning bush with the Huguenot cross.

- The motto of the Church of Scotland is Nec tamen consumebatur, Latin for "Yet it was not consumed", an allusion to the biblical description of the burning bush, and a stylised depiction of the burning bush is used as the Church's symbol. Usage dates from the 1690s.

- The burning bush is also used as the basis of the symbol of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, which uses the Latin motto Ardens sed virens, meaning "Burning but flourishing", and is based on the biblical description of the burning bush. The same logo is used from the separated Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster.

- The burning bush is also the symbol of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, Presbyterian Church in Australia crest, Presbyterian Church of Eastern Australia with the motto in English since its foundation in 1846: 'And the Bush was not consumed', Presbyterian Church in New Zealand, Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, Presbyterian Church in Singapore, Presbyterian Church of Brazil, the Presbyterian Church in Malaysia, the Free Reformed Churches of North America, and the Christian Reformed Churches in the Netherlands.

Islam

[edit]According to the Qur’án, Moses (Musa) departed for Egypt along with his family after completing the time period.[clarification needed] The Qur’án states that during their travel, as they stopped near the Tur, Musa observed a fire and instructed the family to wait until he returned with fire for them.[30] When Musa reached the Valley of Tuwa, God called out to him from the right side of the valley from a tree, on what is revered as Al-Buq‘ah Al-Mubārakah (Arabic: الـبُـقـعَـة الـمُـبَـارَكَـة, "The Blessed Ground") in the Qur’án.[31] Musa was commanded by God to remove his shoes and was informed of his selection as a prophet, his obligation of prayer and the Day of Judgment. Musa was then ordered to throw his rod which turned into a snake and later instructed to hold it.[32][33] The Qur’án then narrates Musa being ordered to insert his hand into his clothes and upon revealing it would shine a bright light. God states that these are signs for the Pharaoh, and orders Musa to invite Pharaoh to the worship of one God.[32]

Baháʼí Faith

[edit]

The Baháʼí Faith understands the Burning Bush to represent the Voice of God. The term Burning Bush appears frequently in the writings of Bahá’u’lláh, the Prophet-Founder of the faith. In the teachings of the Baháʼí Faith, the Voice of God as spoken from the Burning Bush, is now, through the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, speaking directly to humanity; “a Revelation,” Bahá’u’lláh proclaims, "the potency of which hath caused every tree to cry out what the Burning Bush had aforetime proclaimed unto Moses.”[34]

In recounting the association between Moses and the Burning Bush, Bahá’u’lláh writes,

Call thou to mind the days when He Who conversed with God tended, in the wilderness, the sheep of Jethro, His father-in-law. He hearkened unto the Voice of the Lord of mankind coming from the Burning Bush which had been raised above the Holy Land, exclaiming, “O Moses! Verily I am God, thy Lord and the Lord of thy forefathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.” He was so carried away by the captivating accent of the Voice that He detached Himself from the world and set out in the direction of Pharaoh and his people, invested with the power of thy Lord Who exerciseth sovereignty over all that hath been and shall be. The people of the world are now hearing that which Moses did hear, but they understand not. -from Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh[35]

Rastafari

[edit]Some Rastafari believe that the burning bush was cannabis.[36][37]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Exodus 3:1–4

- ^ a b Exodus 3:4

- ^ Cheyne, T. K.; Black, J. S. (1899). "Bush". Encyclopedia Biblica, Volume 1. Toronto: George N. Morang & Company.

- ^ a b Jastrow, M.; Ginzberg, L.; Jastrow, M.; McCurdy, J. F. (1906). "Burning Bush". Jewish Encyclopedia – via JewishEncyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b c d e Peake's commentary on the Bible

- ^ a b Friedman, Richard Elliott (16 August 2005). The Bible with Sources Revealed. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-073065-9.

- ^ Exodus 3:2

- ^ Exodus 3:5

- ^ a b Exodus 3:6

- ^ a b Jewish Encyclopedia, Book of Exodus

- ^ Exodus 3:7

- ^ a b Exodus 3:17

- ^ Exodus 3:14

- ^ Exodus 4:2–4

- ^ Exodus 4:6–7

- ^ a b Exodus 4:9

- ^ Exodus 4:10–13

- ^ Exodus 4:14

- ^ Exodus 4:15–16

- ^ Fleisher, Alexander; Fleisher, Zhenia (January–February 2004). "Study of Dictamnus gymnostylis Volatiles and Plausible Explanation of the "Burning Bush" Phenomenon". Journal of Essential Oil Research. 16 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1080/10412905.2004.9698634. S2CID 95462992.

- ^ Humphreys, Colin (2006). Miracles of Exodus. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 73.

- ^ Kershner, Isabel (31 December 2021). "Is That a Burning Bush? Is This Mt. Sinai? Solstice Bolsters a Claim". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Popa's Tales: The Burning Bush Archived 9 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Jewish Theological Seminary - Home Page". Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Shemot (parashah)

- ^ Bogomolets O. Radomysl Castle-Museum on the Royal Road Via Regia". — Kyiv, 2013 ISBN 978-617-7031-15-3

- ^ The Octoechos, Volume II (St. John of Kronstadt Press, Liberty, TN, 1999), Dogmaticon, Tone II

- ^ Isaiah 9:6 (LXX)

- ^ "The Reformation Study Bible | About | the Symbol of the Burning Bush in Church History".

- ^ Laude, Patrick (2011). Universal Dimensions of Islam: Studies in Comparative Religion. World Wisdom. p. 31. ISBN 9781935493570.

- ^ Patrick Laude (2011). Universal Dimensions of Islam: Studies in Comparative Religion. World Wisdom, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 9781935493570.

- ^ a b Paterson, Andrea C. (2009). Three Monotheistic Faiths - Judaism, Christianity, Islam: An Analysis and Brief History. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781434392466.

- ^ Andrea C. Paterson (2009). Three Monotheistic Faiths – Judaism, Christianity, Islam: An Analysis And Brief History. AuthorHouse. p. 112. ISBN 9781434392466.

- ^ "Bahá'í Prayers | Bahá'í Reference Library". www.bahai.org. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh | Bahá'í Reference Library". www.bahai.org. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Mandito, Ras (2014). The Testament Of Rastafari. Lulu.com. p. 133. ISBN 9781105595653. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Cathcart, Jermaine (2016). Knowledge of Good and Evil: An Urban Ethnography of a Smoking Culture (PDF). Riverside: University of California. p. 37. ISBN 9781369300659. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

External links

[edit]- Icon of the Mother of God "the Unburnt Bush" Icon and Synaxarion of the feast

- The Burning Bush History of the use of the burning bush symbol among Reformed churches