Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula

| Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula | |

|---|---|

St. Michael and St. Gudula's Cathedral | |

| |

| 50°50′52″N 4°21′37″E / 50.84778°N 4.36028°E | |

| Location | Parvis Sainte-Gudule / Sinter-Goedelevoorplein 1000 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region |

| Country | Belgium |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Website | Official website |

| History | |

| Status | Co-cathedral (Cathedral status from 1962) |

| Dedication |

|

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Protected[1] |

| Designated | 05/03/1936 |

| Architectural type | Cathedral |

| Style | |

| Years built | 11th–15th centuries (church) 1485 (façade and towers) |

| Groundbreaking | c. 9th century (chapel) |

| Completed | 1519 |

| Specifications | |

| Number of towers | 2 |

| Number of spires | 2 |

| Spire height | 64 metres (210 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Luc Terlinden (Primate of Belgium) |

| Dean | Claude Castiau |

| Laity | |

| Organist(s) | Xavier Deprez |

The Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula (French: Cathédrale Saints-Michel-et-Gudule; Dutch: Kathedraal van Sint-Michiel en Sint-Goedele[2]), usually shortened to the Cathedral of St. Gudula[a] or St. Gudula[b] by locals, is a medieval Catholic cathedral in central Brussels, Belgium. It is dedicated to Saint Michael and Saint Gudula, the patron saints of the City of Brussels, and is considered to be one of the finest examples of Brabantine Gothic architecture.

The Romanesque church's construction began in the 11th century, replacing an earlier chapel, and was largely complete in its current Gothic form by the 16th, though its interior was frequently modified in the following centuries. The building includes late-Gothic and Baroque chapels, whilst its neo-Gothic decorative elements, including some of its stained glass windows in the aisles, date from restoration work in the 19th century. St. Gudula also stands out for its musical components, notably its two pipe organs and its immense church bells. The complex was designated a historic monument in 1936.[1]

The church was elevated to cathedral status in 1962 and has since been the co-cathedral of the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Mechelen–Brussels, together with St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen.[2] As the national church of Belgium and the Primate of Belgium's official seat, it frequently hosts royal weddings, state funerals and other official ceremonies, such as the Te Deum on Belgian National Day.

Since the mid-20th century, following the construction of the North–South connection, St. Gudula has been situated on the Parvis Sainte-Gudule/Sinter-Goedelevoorplein, a large forecourt east of the Boulevard de l'Impératrice/Keizerinlaan. This area is served by Brussels-Central railway station, as well as by Parc/Park metro station on lines 1 and 5 of the Brussels Metro.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The cathedral's origins are obscure, but historians agree that, as early as the 9th century, a chapel dedicated to Saint Michael probably stood in its place, on what was the most important point of Brussels at the time; the crossroads of two major trade routes—a first one connecting the County of Flanders and Cologne, and another between Antwerp and Mons, then France. These crossroads were located on the Treurenberg hill (French: Mont des pleurs; "Mount of sorrows"), where the St. Gudula Gate stood (integrated in the first city walls), and which was later used as an ominously famous prison, hence its name.[3]

In the 11th century, this first chapel was replaced by a Romanesque church.[4] In 1047, Lambert II, Count of Leuven, and his wife Oda of Verdun, founded a chapter in this church, and organised the transportation to it of the relics of the martyr Saint Gudula, which were housed before then in Saint Gaugericus' Church on Saint-Géry Island (where today's Halles Saint-Géry/Sint-Gorikshallen are located).[5] In 1072, the church was reconsecrated, probably following a fire.[3]

At the end of the 12th century, a Romanesque avant-corps was added to the west of the nave.[6] In the 13th century, Henry I, Duke of Brabant, ordered two round towers to be added to the church. His son, Henry II, Duke of Brabant, instructed the building of a Brabantine Gothic collegiate church in 1226. The choir was constructed between 1226 and 1276. The nave and transept date from the 14th and 16th centuries. The entire church took about 300 years to complete. The main structure was finalised just before Emperor Charles V's reign began in 1519.[7]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the church underwent several modifications, the most remarkable of which was the addition of some chapels: the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament of the Miracle (1534–1539), the Chapel of Our Lady of Deliverance (1649–1655) and the Chapel of St. Mary Magdalen (also called the Maes Chapel) (1672–1675).[8] On 6 June 1579, the collegiate church was pillaged and wrecked by Protestant Geuzen ("Beggars"), and Saint Gudula's relics were disinterred and scattered. In the 1790s, it also suffered looting and destruction by French revolutionaries known as the sans-culottes, including the loss of its original carillon.

-

Miniature of Margaret of York praying in front of the Church of St. Gudula, c. 1468

-

St. Gudula's Church, engraving by Erycius Puteanus, 1646

-

St. Gudula's Church, etching by Pieter Devel from Les délices des Pays-Bas, 1711

-

St. Gudula's Church, painting by Andreas Martin, before 1762

19th century–present

[edit]The church was designated a historic monument on 5 March 1936.[1] In the mid-20th century, it was narrowly spared during the building of the North–South connection, a major railway link through central Brussels. On that occasion, a large forecourt, known as the Parvis Sainte-Gudule/Sinter-Goedelevoorplein, was built in front of it. It was not until 1962, with the creation of the Archdiocese of Mechelen–Brussels, that the collegiate church was promoted to the rank of co-cathedral, when it became the Archbishop's seat, together with St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen.[9] The church's current patron saints, Saint Michael and Saint Gudula, are also those of the City of Brussels.

Restoration work was carried out in the 19th century under the direction of the architect Tilman-François Suys who, from 1839 to 1845, restored the towers and portals,[10] and again in the 20th century under the direction of Jean Rombaux, then Victor Gaston Martiny, chief architect-town planner of the Province of Brabant and member of the Royal Committee for Monuments and Sites. The cathedral was once again thoroughly restored between 1983 and 1999.[9] On those occasions, archaeological excavations were undertaken, which led to the discovery of remains of the Romanesque church and crypt underneath the current choir.[4][9][11]

-

Baptism of Crown Prince Louis-Philippe, son of King Leopold I, in St. Gudula's Church, 1833

-

The church in the early 20th century

-

The street (now demolished) in front of the church, in the 1920s

-

Funeral of Queen Elisabeth at the (by then) cathedral, 30 November 1965

Description

[edit]

Most of the cathedral is in the Brabantine Gothic style, although some parts are in the newer Baroque style. It is traditionally listed, alongside the Chapel Church and the Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon, as one of the three Gothic churches still standing in central Brussels.[12] The cathedral is built of stone from the Gobertange quarry, which is located in present-day Walloon Brabant, approximately 45 km (28 mi) south-east of the cathedral's site.

The building adopts the classic plan: a Latin cross with a three-bay long choir ending in a five-sided apse surrounded by an ambulatory.[6] It is imposing by its sheer size: 110 metres (360 ft) long, 30 metres (98 ft) wide (50 metres (160 ft) at the level of the choir), and 26.5 metres (87 ft) high (the entrance towers reach a height of 69 metres (226 ft)).[3]

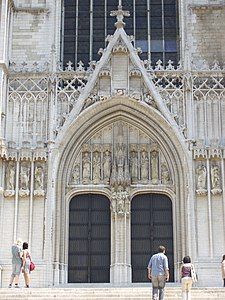

Exterior

[edit]Main façade and towers

[edit]The main (western) façade with its three portals surmounted by gables and two 64-metre-high (210 ft) towers are typical of the French Gothic style, but without a rose window, as it features instead a large ogival window in the Brabantine Gothic style. The whole structure is supported by sturdy flying buttresses with double spans, influenced by Soissons Cathedral, crowned by pinnacles and gargoyles.

The two towers, built between 1470 and 1485, the upper parts of which are arranged in terraces, are attributed to Jan Van Ruysbroeck, the court architect of Philip the Good,[13] who also designed the tower of Brussels' Town Hall and the Collegiate Church of St. Peter and St. Guido in Anderlecht. They appear to be unfinished, lacking the spires seen in other Gothic cathedrals, and were originally meant to be much higher, in a style close to the Town Hall's tower or the north tower of the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp. They nonetheless remain a prominent feature in the skyline of downtown Brussels.

The strong predominance of the vertical lines of this façade is impressive; four robust buttresses close and separate the three portals. The two at the ends become more important by integrating two tall buttressed turrets that rise from the base to the top of the towers themselves. Furthermore, the façade is divided horizontally into three levels: a lower one entirely centred on the three portals; a median one opened by the large multi-light window flanked by two high three-light windows, each inscribed in the axis of one of the towers; and an upper one characterised by the large triangular tympanum which, developing from a gallery with fine columns, is topped by several flaming pinnacles, of which the central, more imposing, reaches a height of 55 metres (180 ft).

-

The western façade

-

The central portal

-

Ogival window and decorative merlon

-

Statue of Saint Michael slaying the dragon

Chapels

[edit]From the transept, on each side of the choir, two large late-Gothic chapels, added in the 16th century (for the northern Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament of the Miracle), and the 17th century (for the southern Chapel of Our Lady of Deliverance), protrude. The large proportion of these chapels gives the impression that the building has three choirs. Behind the apse, on the church's central axis, the Chapel of St. Mary Magdalen (also called the Maes Chapel), in Baroque style, was inserted in 1672–1675 between the buttresses, with an octagonal plan with a dome and lantern.[8]

-

Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament of the Miracle

-

Chapel of St. Mary Magdalen (or Maes Chapel)

Staircase and forecourt

[edit]The monumental staircase in front of the cathedral, designed by Pieter Paul Merckx, was placed in the period 1702–1707. This staircase, a gift from the City of Brussels, was originally built against the city walls to provide access to the promenade on the stretch between the Laeken Gate and the Schaerbeek Gate.

In the centre of the gardens located in front of the cathedral's forecourt stands a bust of King Baudouin. It is the work of the sculptor Henri Lenaerts. The bust was completed on 6 June 1996, and remained at the city's administrative centre until road works on the Rue Sainte-Gudule/Sinter-Goedelestraat were completed. It was integrated into its current environment in 2003–04, as part of the renovation of this green space. It was vandalised in June 2020, following the George Floyd protests in Belgium.[14]

-

View of the monumental staircase

-

Bust of King Baudouin in front of the cathedral

-

Closeup of King Baudouin's bust

Interior

[edit]Nave

[edit]The nave possesses all the characteristics of Brabantine Gothic; the four-part vaults are moderately high and the robust cylindrical columns that line the nave's central aisle are topped with capitals in the shape of cabbage leaves. Statues of the twelve apostles are attached to the columns. These statues date from the 17th century and were created by Lucas Faydherbe, Jerôme Duquesnoy the Younger, Johannes van Mildert and Tobias de Lelis, all renowned sculptors of their time. The statues replaced those destroyed by iconoclasts in 1566. The nave also contains a Baroque pulpit from the 17th century, made by the Antwerp sculptor Hendrik Frans Verbruggen in 1699. The base represents Adam and Eve expelled from the Garden of Eden after plucking the forbidden fruit. At the top, the Madonna and Child piercing the serpent symbolise redemption.[7]

To the right of the portal of the northern transept is an elegant 17th-century sculpture depicting The education of the Holy Virgin by Saint Anna by Jerôme Duquesnoy the Younger after a painting by Rubens.[7] The side aisles contain 17th-century oak confessionals formerly attributed to the sculptor Jan van Delen. The cathedral also contains the unmarked burial place of Dermot O'Mallun, the last Irish-born chief of the name of the O'Moloney sept of Thomond.[15]

-

The nave lined with cylindrical columns supporting the twelve statues of the apostles

-

Adam and Eve expelled from the Garden of Eden, detail of the pulpit

-

Confessional by anonymous (17th century)

Choir and chapels

[edit]The choir is Gothic and has three rectangular bays and a five-sided apse. It also contains the mausoleums of the Dukes of Brabant and Archduke Ernest of Austria made by Robert Colyn de Nole in the 17th century. Its elevation is on three levels; large arcades communicating with the ambulatory, triforium and high windows.

Left of the choir is the Flamboyant Gothic Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament of the Miracle (1534–1539).[16] It now houses the Treasure of the Cathedral, where the famous Drahmal Cross (also known as the Brussels Cross), an early 11th-century Anglo-Saxon inscribed cross-reliquary, is stored. Jean Micault, receiver general of Charles V, and his wife, Livine Cats van Welle, were buried there, and an altarpiece, probably commissioned by their son Nicolas, was dedicated to them. It was made by the Renaissance painter and tapestry designer Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen. This triptych is now in the collections of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium.

Right of the choir is the Chapel of Our Lady of Deliverance (1649–1655), which was built in a late Gothic style and contains a Baroque altar by Jan Voorspoel (1666).[7] Behind the choir is a Baroque chapel dedicated to St. Mary Magdalen (also called the Maes Chapel) dated 1672–1675,[8] and a marble and alabaster altarpiece depicting the Passion of Christ by the sculptor Jean Mone dated 1538.[7]

-

The choir

-

Ceiling

-

The vault of the choir

-

Marble and alabaster altarpiece by Jean Mone (1538)

-

Statue of Saint Gudula

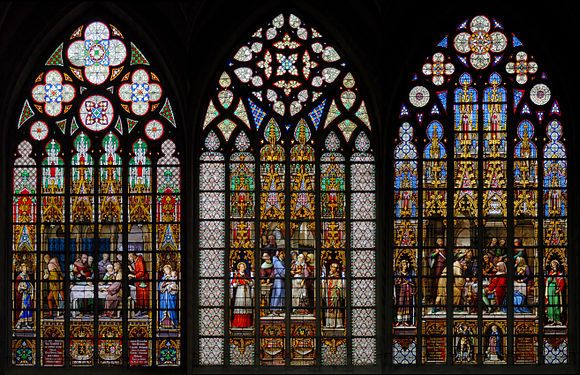

Stained glass

[edit]The cathedral has stained glass windows from the 16th, 17th and 19th centuries; most of which date from between 1525 and 1663. Particularly noteworthy is the large window in the western façade representing the Last Judgement. It was made in 1528 by the Antwerp glassmaker Jan Haeck, based on drawings by Bernard van Orley.

Haeck and Van Orley were also responsible for the windows adorning the northern and southern transepts. The northern window dates from 1537 and represents Charles V and his wife Isabella of Portugal in adoration for the Holy Sacrament and accompanied by their patron saints Charlemagne and Elizabeth of Hungary. The southern window dates from 1538 and represents Charles' brother-in-law, Louis II of Hungary, with his wife Mary of Hungary in adoration for the Holy Trinity and accompanied by Saint Louis and the Virgin Mary.

The Chapel of Our Lady of Deliverance is decorated with stained glass windows by the glass painter Jean De Labaer, based on drawings by Theodoor van Thulden, one of Rubens's pupils. These windows, created between 1654 and 1663, describe the main episodes in the life of the Virgin Mary.

Also worth mentioning are the impressive series of fifteen stained glass windows from the 19th century in the aisles, produced by Jean-Baptiste Capronnier.[17] They were created in 1870 for the celebration of the fifth centenary of the Sacrament of Miracle, an antisemitic canard of host desecration.[9] In 1977, then-Cardinal of Mechelen–Brussels, Leo Joseph Suenens, installed a plaque in the cathedral disavowing the 1370 events.

-

Western façade: stained glass window by Jan Haeck after Bernard van Orley depicting the Last Judgement (1528)

-

Northern transept: stained glass window by Jan Haeck after Bernard van Orley depicting Charles V (1537)

-

Southern transept: stained glass window by Jan Haeck after Bernard van Orley depicting Louis II of Hungary (1538)

-

Three scenes of the Legend of the Sacrament of Miracle. Stained glass windows by Jean-Baptiste Capronnier (c. 1870)

Organs

[edit]The large pipe organ in the nave was inaugurated in October 2000. It hangs as a swallow's nest organ at the level of the triforium, and has a total of 4300 pipes, 63 stops, 4 keyboards and the pedal-board. This instrument is the work of the German organ-builder Gerhard Grenzing, based in Barcelona, in collaboration with the English architect Simon Platt.[9]

The two-manual choir organ was created in 1977 in the workshop of the organ-builder Patrick Collon.[18]

-

Organ by Gerhard Grenzing (2000)

-

Choir organ by Patrick Collon (1977)

Bells

[edit]Both towers contain bells. The south tower contains a 49-bell carillon from 1966 by the Royal Eijsbouts bell foundry, on which Sunday concerts are often given. Out of all the bells in the carillon, only seven of them can ring. They are, from heaviest to lightest: Fabiola, Maria, Michael, Gudula, Philippe, Astrid, and Laurent. Fabiola, Philippe, Astrid and Laurent are named after members of the Belgian royal family.

The north tower contains a single bourdon called Salvator, it was cast by Peter van den Gheyn in 1638. There is also another empty space where a second bourdon used to be. The bourdon has a deep crankshaft, but counterweights have already been removed. There are plans to hang it again on a straight axis with a flying clapper.

| Nr. | Name | Mass (kg) | Note | Tower |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Salvator | 6645 | G0 | North |

| 2 | Fabiola | 3164 | B♯0 | South |

| 3 | Maria | 2298 | C1 | South |

| 4 | Michael | 1628 | D1 | South |

| 5 | Gudula | 1332 | E1 | South |

| 6 | Philippe | 975 | F1 | South |

| 7 | Astrid | 690 | G1 | South |

| 8 | Laurent | 485 | A1 | South |

Trivia

[edit]Falcons in the cathedral

[edit]At the end of the 1990s, local ornithologists discovered a couple of peregrine falcons roosting on top of the cathedral's towers. In 2001, ornithologists of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS) in association with the Fonds d'Intervention pour les Rapaces (FIR), a French association dedicated to the protection of raptors, installed a laying-nest on the edifice in an attempt to encourage nest-building. This laying-nest was never used, but in the spring of 2004, a pair of falcons nested on a balcony on top of the cathedral's northern tower. At the beginning of March, the female laid three eggs.

As a result of watching the three chicks perform acrobatic feats on the cathedral's gargoyles, at the end of May 2004, the project "Falcons for everyone" was developed by the RBINS in association with the Commission Ornithologique de Watermael-Boitsfort. The project installed cameras with a live video stream on their website.[19]

Administration

[edit]The Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula serves as the co-cathedral of the Archbishop of Mechelen–Brussels, the Primate of Belgium, who is currently Archbishop Luc Terlinden. Due to its location in the national capital, it is often used for Catholic ceremonies of national interest, such as royal marriages and state funerals.[20] For example, in 1999, it was the setting for the wedding of Prince Philippe and Mathilde d'Udekem d'Acoz. Other official ceremonies organised in the cathedral include the Te Deum on Belgian National Day, attended by the king and other dignitaries.

See also

[edit]- List of churches in Brussels

- List of cathedrals in Belgium

- List of carillons in Belgium

- Catholic Church in Belgium

- History of Brussels

- Culture of Belgium

- Belgium in the long nineteenth century

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Région de Bruxelles-Capitale (2016). "Cathédrale Saints-Michel-et-Gudule" (in French). Brussels. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula on GCatholic.org

- ^ a b c d "Cathedrale Saints Michel et Gudule". visit.brussels. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ a b Brigode 1938, p. 185–215.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 339.

- ^ a b "Cathédrale Saints-Michel-et-Gudule – Inventaire du patrimoine mobilier". collections.heritage.brussels (in French). Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e History and architecture overview Archived 2012-07-21 at archive.today on the official site of the cathedral

- ^ a b c Mardaga 1994, p. 352.

- ^ a b c d e "History | Brussels Cathedral". Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Des Marez 1918, p. 225.

- ^ Les archéologues ont mis au jour une crypte romane sous l'avant-chœur de Saint-Michel. D'autres trésors enfouis sous la cathédrale. (in French), Le Soir, 16–17 November 1991

- ^ "Eglise Notre Dame de la Chapelle". visit.brussels. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ De Vries 2003, p. 32.

- ^ Pitiot, Christophe (12 June 2020). "A statue of former Belgian King Baudouin defaced with red paint". Euronews. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Moloney, Gerry (3 September 2014). "Resurrecting an ancient chief". History Ireland. History Publications Ltd. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ De Bruyn 1870.

- ^ Mardaga 1994, p. 354.

- ^ "Brussel, Sint Michiels & Sint Goedelekathedraal, koororgel – de Orgelsite | orgelsite.nl" (in Dutch). 20 July 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Falcons for everyone - Peregrine falcons on the cathedral". www.falconsforeveryone.be. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ National events in the Cathedral Archived 2012-07-24 at archive.today on the official site of the cathedral

Bibliography

[edit]- Brigode, Simon (1938). "Les fouilles de la collégiale Sainte-Gudule à Bruxelles : découverte de l'avant-corps occidental de l'époque romane". Annales de la Société royale belge d'archéologie de Bruxelles (in French). 27. Brussels.

- De Bruyn, Abbé H. (1870). Histoire de l'église de Sainte-Gudule et du très-saint sacrement de miracle à Bruxelles (in French). Brussels: Goemare. ISBN 978-0-37170-772-2.

- De Vries, André (2003). Brussels: A Cultural and Literary History. Oxford: Signal Books. ISBN 978-1-902669-46-5.

- Des Marez, Guillaume (1918). Guide illustré de Bruxelles (in French). Vol. 1. Brussels: Touring Club Royal de Belgique.

- Mignon, Jacques (1970). "La cathédrale Saint-Michel". Brabant (Quarterly Review of the Tourist Federation) (in French). 5. Brussels.

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1C: Pentagone N-Z. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1994.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula (Brussels) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula (Brussels) at Wikimedia Commons- Official homepage of the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula

- Virtual visit of the cathedral

- More information about the cathedral

- Discovery guide with pictures of the cathedral

- Observe live falcons at the top of the cathedral

- Roman Catholic churches in Brussels

- Roman Catholic cathedrals in Belgium

- City of Brussels

- Protected heritage sites in Brussels

- Gothic architecture in Belgium

- 11th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in Belgium

- 13th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in Belgium

- 16th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in Belgium

- Roman Catholic churches completed in 1519

- 1047 establishments in Europe

![Choir organ by Patrick Collon [de] (1977)](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/Bruxelles%2C_Cattedrale_dei_SS._Michele_e_Gudula%2C_Organo_Collon.JPG/209px-Bruxelles%2C_Cattedrale_dei_SS._Michele_e_Gudula%2C_Organo_Collon.JPG?auto=webp)