Brooks Sports

| Company type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Sports equipment |

| Founded | 1914 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Founder | John Brooks Goldenberg |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Jim Weber (CEO) |

| Products | Sneakers, clothing |

| Revenue | |

Number of employees | c. 1,100 |

| Parent | Berkshire Hathaway |

| Website | brooksrunning.com |

Brooks Sports, Inc., also known as Brooks Running, is an American sports equipment company that designs and markets high-performance men's and women's sneakers, clothing, and accessories. Headquartered in Seattle, Washington, Brooks products are available in 60 countries worldwide. It is a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway.[2][3][4]

Brooks, founded in 1914, originally manufactured shoes for a broad range of sports. Popular in the mid-1970s, the company faltered in the latter part of the decade, and filed for bankruptcy protection in 1981.[2][5] In 2001, the product line was cut by more than 50% to focus the brand solely on running, and its concentration on performance technology was increased. Brooks Running became the top selling brand in the specialty running shoe market in 2011,[6][7] and remained so through 2017 with a 25% market share.[8]

History

[edit]Early history: Founding, Bruxshu Gymnasium Shoes, Carmen Manufacturing

[edit]

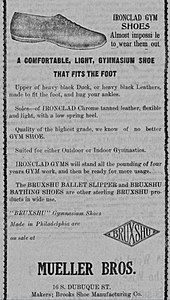

Brooks Sports, Inc. was founded in 1914 by John Brooks Goldenberg, following his purchase of the Quaker Shoe Company, a manufacturer of bathing shoes and ballet slippers.[9] Based in Philadelphia, it operated as a partnership between John Goldenberg and his brothers, Michael and Frank. By 1920, Quaker Shoes had been renamed Brooks Shoe Manufacturing Co., Inc., and its shoes were sold under the brand name Bruxshu. In addition to bathing shoes and ballet slippers, it sold a gymnasium shoe, Ironclad Gyms.[10] The company's innovations included the 1938 introduction of orthopedic shoes for children, Pedicraft,[a] and rubber brakes for roller skates (then known as "quick stops"), patented in 1944.[12]

In 1938, the Goldenbergs bought the Carmen Shoe Manufacturing Company in Hanover, Pennsylvania. Until 1957 a better grade leather was purchased, cut, stitched and fit in Philadelphia, while the same procedure in Hanover used lower grade materials. Both shoes were sold in Philadelphia under the Brooks name, and ranged from inexpensive to high-priced.[13]

In 1956, after a series of operational changes, John notified his brother that he would not renew their partnership agreement, and Michael discussed expanding Carmen with his nephew, Frank's son Barton. In 1957, following the dissolution of the partnership, the existence of Brooks Shoe Manufacturing Company was terminated, and Michael and Barton each acquired 50% of Carmen. In 1958, Michael purchased Barton's interest in the company, and as the sole owner, he renamed Carmen the Brooks Manufacturing Company.[13]

1970s: Introduction of EVA, the Vantage, the Vanguard

[edit]In 1975, Brooks worked with elite runners, including Marty Liquori, a former Olympian, to design a running shoe. The collaboration produced the Villanova, Brooks's first high-performance running shoe.[14] It was the first running shoe to use EVA, an air-infused foam that was later adopted by other athletic brands. Brooks followed the Villanova with the Vantage, a running shoe constructed with a wedge to address overpronation. In 1977, based on newly developed measurements of cushioning, flexibility, and durability.[15] The Vanguard was also introduced in the 1970s. Towards the end of the decade Brooks was among the top three selling brands in the US.[16]

1980s: Bankruptcy, the Chariot, Brooks for Women

[edit]In 1980, as a result of production issues with Brooks's manufacturing facility in Puerto Rico, defective shoes began to arrive at sporting goods stores. Nearly 30 percent of the shoes were returned, and Brooks scrapped 50,000 pairs. The company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and was purchased at auction by footwear manufacturer Wolverine World Wide in 1981.[5][16]

In 1982 Brooks introduced the Chariot, a medial post shoe that featured an angled wedge of harder-density foam in the midsole. It was thicker on the inside of the shoe and tapered toward the outside.[15] In 1987 Brooks launched an anatomically adjusted line of shoes designed for women.[9]

1990s: The Beast, Adrenaline, ownership changes, apparel, Run Happy

[edit]

In 1992, Brooks launched the Beast, a motion control shoe that integrated diagonal rollbar technology. In 1994, the Adrenaline GTS—an abbreviation for go-to shoe—was released. The Adrenaline GTS was built on a semi-curve, an accommodation for runners with a high arch and wide forefoot. The Beast became a best seller, and the Adrenaline GTS went on to become one of the best-selling running shoes of all time.[6][17]

Wolverine moved Brooks away from the niche running market to a generalist athletic brand. The "class to mass" strategy was unsuccessful, and Brooks was sold to Norwegian private equity company The Rokke Group for $21 million in 1993. Brooks moved to Rokke's Seattle location following its acquisition. In 1998, Rokke sold a majority interest in Brooks to J.H. Whitney & Co., a Connecticut private equity firm.[18]

Brooks introduced a full-line of technical running and fitness apparel for women and men in the spring of 1997. It also expanded into the walking category with the introduction of performance walking shoes.[19]

Brooks's Run Happy tag line first appeared in print advertising in 1999.[5] Rather than depicting running as a grueling pursuit, as competitive brands did, Run Happy was based on the idea that runners love running, and suggested that Brooks products allowed "runners to have the running experience they were looking for".[20][14]

2000s: Jim Weber, Berkshire Hathaway, BioMoGo

[edit]In 2001, Jim Weber, a former Brooks board member, was named president and CEO of the company. At the time, the company's market share was low, and bankruptcy had again become a concern. Weber cut lower-priced footwear from the Brooks product line, added an on-site lab and staff engineers, and focused the company on technical-performance running shoes.[21] As the brand was rebuilt, its annual revenue fell to $20 million. Three years later, it was $69 million.[18]

Brooks was acquired by Russell Athletic in 2004. In 2006, Russell was purchased by Fruit of the Loom and Brooks became a subsidiary of Fruit of the Loom's parent company, Berkshire Hathaway. It became an independent subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway in 2011.[18]

In the mid-2000s, Brooks introduced High Performance Green Rubber, a material it developed for outsoles that used sand rather than petroleum.[22] It subsequently developed BioMoGo, a biodegradable mid-sole for running shoes.[23] Brooks estimated that it would cut more than 30 million pounds of landfill waste over a 20-year period. The BioMoGo technology was open source.[24]

2010s: DNA, $500 million milestone, Brooks Heritage

[edit]Brooks DNA (and later Super DNA) was released in 2013. It adapted to the user's gender, weight and pace. It was engineered from non-Newtonian liquid.[25]

In 2011, Brooks became the leading running shoe in the specialty market with revenue of $500 million.[18][2][3]

The Brooks Heritage Collection was launched in 2016, returning the Vanguard, the Chariot, and the Beast to the market. Only the technology was updated; the details of the original shoes, including the colorways, were replicated.[26]

In 2017, Brooks shoes were named Best Running Shoe (The Glycerine and the Launch, Sports Illustrated);[27][28] and Editor's Top Choice (The Adrenaline GTS 18, Runner's World).

Sponsorships

[edit]Brooks sponsors the Brooks Beast Track Club and Hansons-Brooks Distance Project. Some sponsored athletes include, Olympic runner Dathan Ritzenhein,[29] two-time Olympian Kara Goucher,[30]Olympic runner Jess McClain,[31] and three-time Ironman World Champion Chrissie Wellington.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ Ciment, Shoshy (2023-02-21). "Brooks Global Sales Hit $1.2 Billion in 2022 As the Running Category Soars". Footwear News. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ a b c Tracy, Abigail (April 24, 2014). "How Brooks Reinvented Its Brand". Inc. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ a b Thomas, Lauren (October 30, 2017). "Brooks Running sees double-digit sales growth despite unpredictability of sports retail". CNBC. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Koopmans, Kelley (February 23, 2017). "How Brooks Running came back from the edge". KOMO News. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Garnick, Coral (June 19, 2014). "Brooks Sports running strong at 100". Seattle Times. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ a b Karlson, Dana (January 21, 2015). "Brooks Sprints Into 2015, Holds Top Spot with Runners". Footwear News. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Max, Sarah (July 29, 2014). "Brooks Sports Moves New Home Closer to Trails". New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Wahba, Phil (February 1, 2018). "A Kindred Sole". Fortune (Print edition): 30. ISSN 0015-8259.

- ^ a b FN Staff (May 12, 2014). "Milestone: Brooks Looks Back at 100 Years". Footwear News. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Ironclad Gym Advertisement" (PDF). Daily Iowan. February 25, 1920. p. 5. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "Column". Frederick News. September 29, 1966. p. 14. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "US patent US2343007". US Patent Office (Via Google), 1944. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b "United Shoe Workers of America vs. Brooks vs. Brooks Manufacturing Co". justia.com. US District Court for Eastern Pennsylvania. May 2, 1960. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b Terjesen, S. and, Argue, E. (2001). "Run Happy: Entrepreneurship at Brooks". International Journal of Sports Management and Marketing. 7 (1/2): 133–139. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Beverly, Jonathan (November 18, 2016). "50 Years of (Mostly) Fantastic Footwear Innovation". Runners World. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b Gupta, Hamanee (June 21, 1994). "If the Shoe Fits: Firm Seeks Bigger Foothold In Market". Seattle Times. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ RW staff (September 10, 2013). "Wayback Wonders". Runner's World. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d Cunningham, Lawrence A. (October 21, 2014). Berkshire Beyond Buffett: The Enduring Value of Values. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 154, 155. ISBN 9780231170048. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "Apparel World: Companies". Apparel International: The Journal of the Clothing and Footwear Institute. 28. 1997.

- ^ Elliot, Stuart (January 27, 2014). "New Running Shoe Line Says, 'Come Fly With Me'". New York Times. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- ^ Wahba, Bill (October 21, 2014). "How Buffett's Brooks Running plans to become a $1 billion brand". Fortune. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Orlovi, Orlovic (June 27, 2016). "URBANMEISTERS SELECTS THEIR FAVORITE BRAND". Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Schwartz, Ariel (June 29, 2009). "Brooks Designs a Sustainable Running Shoe From the Bottom Up". Fast Company. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Staff (June 10, 2009). "Brooks' BioMoGo Midsoles – a lighter impact". Alternative Consumer. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Jones, Riley (June 4, 2013). "Know Your Tech: Brooks DNA". Complex. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Forester, Pete (October 21, 2016). "The Heritage Sneaker Brand You Need on Your Radar". Esquire. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "Best Women's Running Shoes". Sports Illustrated. April 4, 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ SI Staff (March 14, 2017). "The Best Men's Running Shoes 2017". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "New Sponsor, New Attitude. Can Dathan Ritzenhein Make the 2020 Olympic Team?". Runner's World. 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ Battaglia, Joe (2024-01-29). "Kara Goucher Signs Footwear Deal With Brooks". FloTrack. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ "Olympic Alternate Jess McClain Signs Sponsorship Contract With Brooks". Runner's World. 2024-03-25. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ Hichens, Liz (2010-01-19). "Brooks Sports Partners With Three-Time Ironman World Champion Chrissie Wellington". Triathlete. Retrieved 2024-12-05.