Born Again (Black Sabbath album)

| Born Again | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 9 September 1983 | |||

| Recorded | May–June 1983[1] | |||

| Studio | The Manor, Oxfordshire | |||

| Genre | Heavy metal | |||

| Length | 41:00 | |||

| Label | Vertigo | |||

| Producer | Black Sabbath, Robin Black | |||

| Black Sabbath chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Born Again | ||||

| ||||

Born Again is the eleventh studio album by English rock band Black Sabbath. Released on 9 September 1983,[2] it is the only album the group recorded with lead vocalist Ian Gillan, then-formerly of Deep Purple. It was also the last Black Sabbath album for 9 years to feature original bassist Geezer Butler and the last to feature original drummer Bill Ward, though Ward did record one studio track with the band 15 years later on their 1998 live album Reunion. The album has received mixed reviews from critics,[3] but was a commercial success upon its 1983 release, reaching No. 4 in the UK charts.[4] The album also hit the top 40 in the United States.[5] In July 2021, guitarist and founding member Tony Iommi confirmed that the long lost original master tapes of the album had been finally located, and that he was considering remixing the album for a future re-release.[6]

Origins

[edit]Following the departure of vocalist Ronnie James Dio and drummer Vinny Appice in 1982, Sabbath's future was in doubt. The band switched management to Don Arden (Sharon Osbourne's father) and he suggested Ian Gillan as the new vocalist.[7] The band had considered vocalists such as Robert Plant and David Coverdale before settling on Gillan.[8] With Whitesnake on the verge of breaking up, Iommi was eager to form a new group with Coverdale and drummer Cozy Powell joining him and Butler, but Coverdale and Powell decided at the last minute to continue with Whitesnake (the latter would eventually join Black Sabbath in 1988).[9] While Iommi has claimed that the band received an audition tape from a then-unknown Michael Bolton at this time,[7] Butler claims no such thing happened and that Iommi concocted the story as "a joke".[9] This claim has also been refuted by Bolton himself, who clarified that it was "only a rumour".[10]

Iommi told Hit Parader magazine in late 1983 that Gillan was the best candidate, saying "His shriek is legendary." Gillan was at first reluctant, but his manager convinced him to meet with Iommi and Butler at The Bear, a pub in Oxford. After a night of heavy drinking,[7] Gillan officially committed to the project in February 1983.[11] The following morning Gillan had no memory of joining the band and claimed he didn't even like Black Sabbath's music, but the deal had already been struck.[9]

The project was originally intended to be a new supergroup, and the members of the group had no intention of billing themselves as Black Sabbath.[7] At some point after recording had been completed, Arden insisted that they use the recognizable Sabbath name, and the members were overruled.[7] Arden had secured a sizable advance from the record company with the proviso that Gillan be involved, and they would only release the album under the Black Sabbath name.[9] "We thought we were doing a kind of Gillan-Iommi-Butler-Ward album…" recalled bassist Geezer Butler. "That is the way we approached the album. When we had finished the album, we took it to the record company and they said, 'Well, here's the contract: it is going to go out as a Black Sabbath album."[12]

With Cozy Powell electing to remain with Coverdale in Whitesnake, Black Sabbath's longtime drummer Bill Ward was persuaded to return to the band. Ward claimed to be newly sober after leaving the band in 1980 to deal with his alcoholism[13] and he assured Iommi and Butler that he was up to recording and touring once again.[9] Ward began drinking at some point during the sessions and returned to Los Angeles for treatment once the album was completed, and has remained sober ever since.[7] Ward has said that he enjoyed making the album, which remains his final studio album with the band.[14]

Recording

[edit]Sabbath began recording in May 1983 at Richard Branson's Manor Studio, in the Oxfordshire countryside.[15] Engineer Robin Black had worked with the band in the mid-1970s on Sabotage and received a co-producer credit on Born Again.

During recording, the band members lived at Manor Studio while Gillan chose to live outside the house, alone, in a marquee tent on the studio grounds: "I thought he was joking, but when I arrived at the Manor I saw this marquee outside and I thought, fucking hell, he's serious. Ian had put up this big, huge tent. It had a cooking area and a bedroom and whatever else", said Iommi. Butler said that the tent situation and Gillan's refusal to live with his new bandmates, in hindsight, likely indicated that the vocalist didn't view himself as a member of the band.[9]

"Ian's lyrics were about sexual things or true facts, even about stuff that happened at The Manor there and then," Iommi said. "They were good, but quite a departure from Geezer's and Ronnie's lyrics." For example, Gillan returned from a local pub one evening, took a car belonging to drummer Ward, and commenced racing around a go-cart track on the Manor Studio property. He crashed the car, which burst into flames after he escaped uninjured. He wrote the album's opening "Trashed" about the experience.[7] Butler felt that Gillan's lyrics on tracks such as "Digital Bitch" and "Keep It Warm" were good, but much better suited to the musical style of Deep Purple than Black Sabbath.[9]

"Disturbing the Priest" was written after a rehearsal space – set up by Iommi in a small building near a local church – received noise complaints from the resident priests.[7] "We wanted this effect on 'Disturbing the Priest'," recalled the guitarist, "and Bill got this big bucket of water and he got this anvil. It was really heavy, and he'd got it hanging on a piece of rope and lower it in to get this effect: hit it and lower it in, and then lift it out again. It was a great effect, but it took hours to do."[16]

The band got along well, but it became apparent to all involved that Gillan's style did not quite mesh with the Sabbath sound. In 1992, he told director Martin Baker, "I was the worst singer Black Sabbath ever had. It was totally, totally incompatible with any music they'd ever done. I didn't wear leathers, I wasn't of that image...I think the fans probably were in a total state of confusion." In 1992, Iommi admitted to Guitar World, "Ian is a great singer, but he's from a completely different background, and it was difficult for him to come in and sing Sabbath material."

"I saw Ian go into the studio one day," Ward recalled, "and I was fortunate and honoured, actually, to be part of a session. I watched him lay tracks on 'Keep It Warm'… I felt like Ian was Ian in that song… I watched this incredible transformation of this man that really, I felt, delicately put lyrics together. It made sense. I thought he did an excellent job. And I really dig that song too."[17]

"I did some of the best drum work on that album…" Bill Ward recalled. "On 'Disturbing the Priest', there were some polyrhythms and some counterpoint things that I was doing, and I was using at least twenty different pieces of percussion towards the end of that song… I was real proud of a lot of the work that I did. Some of it invariably got lost in the mix, but I know that it's printed on those tracks."[18] Butler said that Ward began acting quite strangely during recording and was angrier than he had ever seen him. At one point the drummer began hallucinating and had to be hospitalized, and while he was there the band discovered his secret stash of vodka that he'd been consuming in secret at night. After being released from the hospital, Ward quit the band again and returned to America to sort out his issues, with his drum parts already recorded.[9]

When the band heard the final product, they were horrified at the muffled mix. In his autobiography, Iommi explains that Gillan inadvertently blew a couple of tweeters in the studio speakers by playing the backing tracks too loud and nobody noticed. "We just thought it was a bit of a funny sound, but it went very wrong somewhere between the mix and the mastering and the pressing of that album...the sound was really dull and muffly. I didn't know about it, because we were already out on tour in Europe. By the time we heard the album, it was out and in the charts, but the sound was awful." Butler recalled listening to the tapes in his hotel room and being alarmed at how "muffled and unclear" the tracks were, but Iommi and Black assured him that the issue would be corrected during mixing. Ultimately, the issue never was corrected, with Butler lamenting years later that "that's what happens when you don't hire a bona fide producer, like Martin Birch, to handle things."[9]

For all his misgivings, Gillan remembers the period fondly, stating in the Black Sabbath: 1978–1992 documentary, "But by God, we had a good year...And the songs, I think, were quite good."

Breakup

[edit]After Bill Ward had left the band for rehab, former Electric Light Orchestra drummer Bev Bevan was hired for the subsequent tour. Bevan was a friend of Iommi's who knew Don Arden well, but he was ultimately not a heavy metal drummer.[9] Following the tour, in which Gillan refused to learn the lyrics to much of the band's Osbourne-era material, this version of Black Sabbath fell apart, with Gillan and Bevan quitting.[9]

The tour was also a breaking point for Butler, who admits in the Black Sabbath: 1978–1992 documentary, "I just got totally disillusioned with the whole thing and I left some time in 1984 after the Born Again tour. I just had enough of it." In 2015 Butler clarified to Dave Everley of Classic Rock: "I left because my second child was born and he was having problems, so I wanted to stay with him. I told Tony I couldn't concentrate on the band anymore. But I never fell out with anybody." While the members all got along well enough, Butler questioned Gillan's commitment after his refusal to learn the lyrics to the band's older material, and Butler says the looming Deep Purple reunion was the deciding factor in the vocalist's decision to leave. Iommi was unhappy when Gillan told him the news, as he thought it had been a long-term arrangement.[19][9] Disagreements with management also contributed to the band's dissolution.[19]

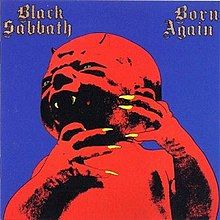

Album cover

[edit]The Born Again album cover – depicting what Martin Popoff described as a "garish red devil-baby" – is by Steve 'Krusher' Joule, a Kerrang! designer who also worked on Ozzy Osbourne's Speak of the Devil. It is based on a black-and-white photocopy of a photograph published in a 1968 magazine.[20] Joule was said to have deliberately delivered a sub-par cover due to his involvement with and loyalty to the band's former vocalist Osbourne.[9]

Butler called the cover "a bit sick, but (Arden) loved it, so that was that."[9] Gillan told the press that he vomited when he first saw the picture. However, Iommi approved the cover,[21] which has long been regarded as one of the worst in rock music history.[3] Ben Mitchell of Blender called the cover "awful".[22] The British magazine, Kerrang!, ranked the cover in second place, behind only the Scorpions' Lovedrive, on their list of "10 Worst Album Sleeves in Metal/Hard Rock". The list was based on votes from the magazine's readers.[23] NME included the sleeve on their list of the "29 sickest album covers ever"[24] and Metal Hammer included it on their list of "50 most hilariously ugly rock and metal album covers ever".[25] Sabbath's manager Don Arden was quite hostile towards the band's ex-vocalist Ozzy Osbourne, who had recently married his daughter Sharon,[26] and was fond of telling Osbourne that his children resembled the Born Again cover.[26]

Release and reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Metal Forces | 8/10[27] |

| Martin Popoff | 10/10[28] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Smash Hits | 4/10[30] |

Born Again was released in September 1983 and was a commercial success. It was the highest charting Black Sabbath album in the United Kingdom since Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (1973), and became an American Top 40 hit.[31] Despite this, it was the first Black Sabbath album to fall short of RIAA certification.

The album received mixed reviews upon its release.[32] AllMusic's Eduardo Rivadavia wrote that the album has "gone down as one of heavy metal's all-time greatest disappointments" and described "Zero the Hero", "Hot Line", and "Keep It Warm" as "embarrassing".[3] Blender contributor Ben Mitchell gave the album one out of five stars and claimed that the music on Born Again was worse than its cover.[22] Martin Charles Strong, the author of The Essential Rock Discography, wrote that it was "an exercise in heavy-metal cliché".[33] However, PopMatters contributor Adrien Begrand has noted the album as "overlooked".[32] The British magazine Metal Forces defined it "a very good album" even if "Gillan may not be the perfect frontman for the Sabs".[27]

Despite the overall negative reception with critics, the album remains a fan favorite. Author Martin Popoff has written that "if any album in the history of Black Sabbath is getting a new set of horns up from metalheads here deep into the new century, it's Born Again."[11] Industrial metal band Godflesh and death metal band Cannibal Corpse both have covered "Zero the Hero", the former appears on the Masters Of Misery - Black Sabbath: The Earache Tribute album while the latter is featured on the Hammer Smashed Face EP. Cannibal Corpse's former singer, Chris Barnes, has called Born Again his favourite Black Sabbath album.[34] "Zero the Hero" has also been cited as the inspiration for the Guns N' Roses hit "Paradise City",[35] and in his autobiography Iommi also suggests the Beastie Boys may have borrowed the riff from "Hot Line" for their hit "(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!)". Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich has called Born Again "one of the best Black Sabbath albums".[36] Bill Stevenson, former drummer of Black Flag, stated the band was listening to the album around the time of My War, defining songs like "Trashed" and "Disturbing the Priest" as "ideal".[37] Iron Maiden vocalist Bruce Dickinson has also defended the album, saying "'Born Again' — great album. Everybody goes, 'Oh, forget that one.' No, it's a great album."[38]

In 1984, Ozzy Osbourne stated that the album was the "best thing I've heard from Sabbath since the original group broke up".[39] Butler has pointed to "Zero the Hero" and "Disturbing the Priest" as his favorites on the album.[19] Butler has said that while he initially felt that the poor production had spoiled Born Again, upon re-listening to it decades later "it was a lot better than I remembered", saying "If the songs are good enough, you can get away with iffy production." He points to Iommi's riffs and says "Ian's singing is great".[9] In 1992, Iommi confessed to Guitar World, "To be honest, I didn't like some of the songs on that album, and the production was awful. We never had time to test the pressings after it was recorded, and something happened to it by the time it got released."

Ian Gillan expressed disappointment in the final production mix of the album, saying that although he did not break his first copy of it, "I threw it out the window of my car. [Laughs]" He also reflected on the touring activity with the band, "I was with Black Sabbath for a year and I sang Ozzy Osbourne songs as well as the songs from Born Again. And I never felt right doing that. It was great — I could sing them okay — but I didn't sound like Ozzy. There was something not quite right."[40]

A re-mastered 'Deluxe Expanded Edition' of Born Again was released in May 2011 by Sanctuary Records. It included several live tracks from the 1983 Reading Festival originally featured on BBC Radio 1's Friday Rock Show. Though the release was remastered, it was not remixed due to the inability to locate the original master tapes, as well as Sanctuary not wanting delay the release in an effort to locate said tapes for a remix.[41]

In 2021, Tony Iommi claimed that the original master tapes, long thought lost, had been found and that he was considering remixing them for an eventual release.[42][43]

Born Again Tour and Stonehenge props

[edit]According to Iommi's autobiography, Ward began drinking again near the end of the Born Again recording sessions and returned to Los Angeles for treatment. The band recruited Bev Bevan, who had played with The Move and ELO,[44] for the upcoming tour in support of the new album. Gillan had all the lyrics to the Sabbath songs written out and plastered all over the stage, explaining to Martin Baker in 1992, "I couldn't get into my brain any of these lyrics...I cannot soak in these words. There's no storyline. I can't relate to what they mean." Gillan attempted to overcome the problem by having a cue book with plastic pages on stage, which he would turn with his foot during the show. However, Gillan did not anticipate the "six buckets" of dry ice that engulfed the stage, making it impossible for the singer to see the lyric sheets. "Ian wasn't very sure-footed either," Iommi writes in his memoir. "He once fell over my pedal board. He was waving at the people, stepped back and, bang!, he went arse over head big time." Gillan also told Birch that it was Don Arden's idea to open the show with a crying baby blaring over the speakers and a dwarf made to look exactly like the demonic baby depicted on the Born Again album cover miming to the screaming. "We noticed a dwarf walking around the day before the opening show...And we're saying to Don, 'We think this is in the worst possible taste, this dwarf, you know?' And Don's going, 'Nah, the kids will love it, it'll be great.'"

The tour is most infamous, however, for the gigantic Stonehenge props the band used. Iommi recalls in his autobiography that it was Butler's idea but the designers took his measurements the wrong way and thought it was meant to be life-size. Months later, while rehearsing for the tour at the Birmingham NEC, the stage set arrived. "We were in shock," writes Iommi. "This stuff was coming in and in and in. It had all these huge columns in the back that were as wide as your average bedroom, the columns in front were about 13 feet high, and we had all the monitors and the side fills as well as all this rock. It was made of fiberglass and wood, and bloody heavy." The set would be lampooned in Rob Reiner's 1984 rock music mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap, with the band having the opposite problem of having to use miniature Stonehenge stage props. Butler has said that he told the associate scriptwriter of the film the story of the band's performances with their "Stonehenge" stage props.[45] In an interview for the documentary Black Sabbath: 1978–1992, Gillan claims Don Arden had the dwarf walk across the top of the Stonehenge props at the start of the show and, as the tape of the screaming baby faded away, fall back "from about thirty-five feet in the air on this big pile of mattresses. And then, 'Dong!' The bells start and the monks come out, the whole thing. Pure Spinal Tap." The band toured Europe first, playing the Reading Festival (a performance that is included on the 2011 deluxe edition of Born Again) and also playing in a bullring in Barcelona in September. Sabbath performed Gillan's hit with Deep Purple, "Smoke on the Water", on the tour, with Iommi explaining in his memoir, "it seemed like a bum deal for him not to do any of his stuff while he was doing all of ours. I don't know if we played it properly but the audience loved it. The critics moaned; it was something out of the bag and they didn't want to know then." In October, the band took the Stonehenge set to America but could only use a portion of it at most gigs because the columns were too high. The set was eventually abandoned. A music video for "Zero the Hero" was also released, featuring performance footage of the band onstage interspersed with scenes involving several grotesque characters performing experiments on a witless young man in a haunted house filled with rats, roosters and a roaming horse.

Track listing

[edit]Standard edition

[edit]All songs credited to Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler, Bill Ward, and Ian Gillan, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Trashed" | 4:15 |

| 2. | "Stonehenge" (instrumental) | 1:57 |

| 3. | "Disturbing the Priest" | 5:48 |

| 4. | "The Dark" (instrumental) | 0:45 |

| 5. | "Zero the Hero" | 7:35 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6. | "Digital Bitch" | 3:37 | |

| 7. | "Born Again" | 6:34 | |

| 8. | "Hot Line" | Iommi, Butler, Gillan | 4:51 |

| 9. | "Keep It Warm" | Iommi, Butler, Gillan | 5:38 |

| Total length: | 41:00 | ||

2011 deluxe edition disc 2

[edit]Tracks 3-11 recorded live at the Reading Festival on Saturday, August 27, 1983 and first aired on Friday Rock Show via BBC Radio 1.[41]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Fallen" (previously unreleased album session outtake) | 4:30 |

| 2. | "Stonehenge" (extended version) | 4:47 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3. | "Hot Line" | 4:55 | |

| 4. | "War Pigs" | Butler, Iommi, Ozzy Osbourne, Ward | 7:25 |

| 5. | "Black Sabbath" | Butler, Iommi, Osbourne, Ward | 7:11 |

| 6. | "The Dark" | 1:05 | |

| 7. | "Zero the Hero" | 6:55 | |

| 8. | "Digital Bitch" | 3:34 | |

| 9. | "Iron Man" | Butler, Iommi, Ozzy Osbourne, Ward | 7:41 |

| 10. | "Smoke on the Water" | Ritchie Blackmore, Gillan, Roger Glover, Jon Lord, Ian Paice | 4:56 |

| 11. | "Paranoid (Features a reprise of "Heaven and Hell")" | Butler, Iommi, Ozzy Osbourne, Ward | 4:18 |

Personnel

[edit]Black Sabbath

- Ian Gillan – vocals

- Tony Iommi – guitars, guitar effects, flute

- Geezer Butler – bass, bass effects

- Bill Ward – drums, percussion

Additional musicians

- Geoff Nicholls – keyboards

- Bev Bevan – drums (on 2011 Deluxe Edition – Disc 2, tracks 3–11)

Credits[46]

- Steve Barrett – art assistant

- Black Sabbath – producer

- Robin Black – producer, engineer

- Stephen Chase – engineer, assistant engineer

- Paul Clark – co-ordination

- Hugh Gilmour – liner notes, design, reissue design, original sleeve design

- Ross Halfin – photography

- Steve Joule – artwork, cover design

- Peter Restey – equipment technician

- Ray Staff – remastering

- Chris Walter – photography

Release history

[edit]| Region | Date | Label |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 9 September 1983 | Vertigo Records |

| United States | 1983 | Warner Bros. Records |

| Canada | 1983 | Warner Bros. Records |

| United Kingdom | 22 April 1996[47] | Castle Communications |

| United Kingdom | 2004 | Sanctuary Records |

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1983) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[48] | 53 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[49] | 37 |

| Finnish Albums (The Official Finnish Charts)[50] | 6 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[51] | 37 |

| Japanese Albums (Oricon)[52] | 38 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[53] | 44 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[54] | 14 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[55] | 7 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[56] | 4 |

| US Billboard 200[57] | 39 |

| Chart (2011) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Rock & Metal Albums (OCC)[58] | 19 |

References

[edit]- ^ "Born Again sessions". Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Music Week" (PDF). p. 37.

- ^ a b c d Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Born Again > Overview". Allmusic. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "Gillan the Hero". Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "Billboard Top 200". Billboard. Retrieved 1 November 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Blabbermouth (26 June 2021). "TONY IOMMI Says Original Tapes For BLACK SABBATH's 'Born Again' Album Have Been Found: 'I'm Thinking Of Remixing' It". BLABBERMOUTH.NET. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Iommi, Tony (2011). Iron Man: My Journey Through Heaven and Hell with Black Sabbath. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306819551.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2006). Black Sabbath: Doom Let Loose: An Illustrated History. ECW press. p. 201. ISBN 1-55022-731-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Butler, Terence (2023). Into the Void. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-324250-0.

- ^ Kaufman, Spencer (9 March 2020). "Tony Iommi Recalls Michael Bolton Auditioning for Black Sabbath". Consequence.net. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ a b Popoff, Martin (2006). Black Sabbath: Doom Let Loose: An Illustrated History. ECW press. p. 198. ISBN 1-55022-731-9.

- ^ Swedish TV interview, broadcast April 1994, transcribed by Ola Malmström in Sabbath fanzine Southern Cross #14, p19, October 1994

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2006). Black Sabbath: Doom Let Loose: An Illustrated History. ECW press. p. 197. ISBN 1-55022-731-9.

- ^ Wright, Michael. "Bill Ward Tells Sabbath Tales and Talks Reunion". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2004). Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story. ECW Press. p. 234. ISBN 1-55022-618-5.

- ^ Scott, Peter (May 1998). "Tony Iommi Interview". Southern Cross (Sabbath fanzine) #21. p. 46.

- ^ Schroer, Ron (October 1996). "Bill Ward and the Hand of Doom – Part III: Disturbing the Peace". Southern Cross (Sabbath fanzine) #18. p. 24.

- ^ Schroer, Ron (October 1996). "Bill Ward and the Hand of Doom – Part III: Disturbing the Peace". Southern Cross (Sabbath fanzine) #18. p. 25.

- ^ a b c "Geezer Butler Discusses Veganism, Religion, Politics, Surveillance, and Life Lessons". bryanreesman.com. 27 March 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ Siegler, Joe. "Black Sabbath Online: Born Again". Black Sabbath Online. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

...the first image of a baby that I found was from the front cover of a 1968 magazine called Mind Alive [...] we bashed the whole thing out in a night

– Steve Joule interview - ^ Popoff, Martin (2006). Black Sabbath: Doom Let Loose: An Illustrated History. ECW press. p. 206. ISBN 1-55022-731-9.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Ben. "Born Again – Blender". Blender. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ "BLABBERMOUTH.NET – 10 Worst Album Sleeves in Metal/Hard Rock". Blabbermouth.net. Archived from the original on 27 August 2004. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Pictures of NSFW - the 29 sickest album covers ever - Photos - NME.COM". NME. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Young, Simon (9 May 2023). "The 50 most hilariously ugly rock and metal album covers ever". Metal Hammer. Future plc. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ a b Osbourne, Ozzy (2011). I Am Ozzy. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0446569903.

- ^ a b Barnell, Graham (1983). "Black Sabbath – Born Again". Metal Forces (2). Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (1 November 2005). The Collector's Guide to Heavy Metal: Volume 2: The Eighties. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Collector's Guide Publishing. ISBN 978-1-894959-31-5.

- ^ "Black Sabbath: Album Guide". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ Dellar, Fred (29 September – 12 October 1983). "Albums: Black Sabbath — Born Again (Polydor)" (PDF). Smash Hits. Vol. 5, no. 20. Peterborough: EMAP National Publications, Ltd. p. 21. ISSN 0260-3004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023 – via World Radio History.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2004). Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story. ECW Press. p. 237. ISBN 1-55022-618-5.

- ^ a b Begrand, Adrien. "Alice Cooper: Portrait of the Artist as a Burnt-Out Old Man < PopMatters". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ Strong, Martin Charles (2006). The Essential Rock Discography. Canongate Books Ltd. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-84195-827-9.

- ^ Mudrian, Albert, ed. (2009). Precious Metal: Decibel Presents the Stories Behind 25 Extreme Metal Masterpieces. Da Capo Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-306-81806-6.

Black Sabbath Born Again.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2006). Black Sabbath: Doom Let Loose: An Illustrated History. ECW press. p. 210. ISBN 1-55022-731-9.

- ^ "BLABBERMOUTH.NET – METALLICA's LARS ULRICH: 'Metal Is Like Herpes — It Never Goes Away'". Blabbermouth.net. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Blush, Steven; Petros, George (2001). American Hardcore: A Tribal History. Feral House. p. 73. ISBN 9780922915712.

- ^ "Bruce Dickinson Says This Divisive Black Sabbath Record Is Much Better Than People Say: 'It's Great'". ultimate-guitar.com. 22 May 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ Hogan, Richard."Is Sabbath turning Purple?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2005. Retrieved 2012-07-11.. Circus Magazine 02-29-84

- ^ "IAN GILLAN Was 'Disappointed' With 'Final Production Mix' Of BLACK SABBATH's 'Born Again': 'I Threw It Out The Window Of My Car'". Blabbermouth.net. 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ a b Blabbermouth (12 April 2011). "BLACK SABBATH's 'Born Again' Deluxe-Expanded-Edition Reissue Was Remastered, Not Remixed". Blabbermouth.net. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "TONY IOMMI Says Original Tapes For BLACK SABBATH's 'Born Again' Album Have Been Found: 'I'm Thinking Of Remixing' It". Blabbermouth.net. 26 June 2021. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Black Sabbath: Tony Iommi Considera Remixar O Álbum Born Again E Lançar Box Com Discos Da Era Tony Martin". Rockbizz.com.br. 26 June 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Bevan, who was still a member of ELO in 1983, had a long-time relationship with Don Arden, as all of ELO's albums from 1975's Face the Music forward were recorded for Arden's Jet Records label.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2006). Black Sabbath: Doom Let Loose: An Illustrated History. ECW press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 1-55022-731-9.

- ^ "Born Again > Credits". Allmusic. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Born Again – Black Sabbath Online". black sabbath.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 19. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 4371a". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin – levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. ISBN 978-951-1-21053-5.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Black Sabbath – Born Again" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005 (in Japanese). Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Black Sabbath – Born Again". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Black Sabbath – Born Again". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Black Sabbath – Born Again". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Black Sabbath Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Official Rock & Metal Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Born Again at Discogs (list of releases)