David Koresh

David Koresh | |

|---|---|

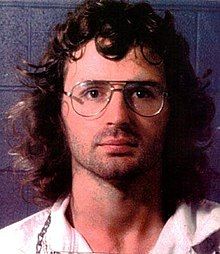

Photograph of Koresh taken in 1987 by police after his arrest. | |

| Born | Vernon Wayne Howell August 17, 1959 Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | April 19, 1993 (aged 33) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound to the head or fire wounds sustained in the Waco siege |

| Body discovered | Mount Carmel Center McLennan County, Texas, U.S. |

| Resting place | Tyler Memorial Park Cemetery, Tyler, Texas 32°21′23″N 95°22′03″W / 32.35640°N 95.36750°W |

| Occupation | Leader of the Branch Davidians cult |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | Rachel Jones |

| Children | 16[1] |

David Koresh (/kəˈrɛʃ/[citation needed]; born Vernon Wayne Howell; August 17, 1959 – April 19, 1993) was an American cult leader[2] who played a central role in the Waco siege of 1993.[3][4] As the head of the Branch Davidians, a religious sect, Koresh claimed to be its final prophet. His apocalyptic Biblical teachings, including interpretations of the Book of Revelation and the Seven Seals, attracted various followers.[5]

Coming from a dysfunctional background, Koresh was a member and later a leader of the Branch Davidians, a movement originally led by Benjamin Roden, based at the Mount Carmel Center outside Waco, Texas. There, Koresh competed for dominance with another leader, Benjamin Roden's son George, until Koresh and his followers took over Mount Carmel in 1987. In the early 1990s, he became subject to allegations about polygamy and child sexual abuse by former Branch Davidian associates.

Further allegations related to the Branch Davidians' stockpiling of weapons led the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) and later the FBI to launch a raid on the group's Mount Carmel compound in February 1993. During the 51-day siege and violence that ensued, Koresh was wounded by ATF forces and later died of a gunshot in unclear circumstances as the compound was destroyed in a fire.

Early life

[edit]Some details of Koresh's life vary among sources, but he was born Vernon Wayne Howell on August 17, 1959, in Houston, Texas, to unmarried[6] parents: 20-year-old Bobby Wayne Howell and 14-year-old Bonnie Sue Clark. Two years after the birth, the relationship broke down.[7] Bonnie continued to flounder, with an abusive, first marriage to a Joe Golden quickly ending in divorce.[7] After this, around 1962, unable to cope with her situation, Bonnie moved away to Dallas.[8] She placed her son in the care of her mother and an older sister: Bonnie's mother would pretend to be Koresh's mother; Bonnie would pose as an aunt when she occasionally visited him.[9]

With her marriage, in 1964, to merchant marine Roy Haldeman, however, Bonnie at last felt in a stable enough position to raise her son herself. The truth about who was his real mother was thus revealed to a five-year-old Koresh, an experience he carried with him his whole life.[10] To make a tumultuous situation still worse, it was at this time that Koresh said he began to be sexually abused by one of his mother's male relatives.[11] In July 1965, not long before Koresh turned six, a half-brother, Roger, arrived; a few weeks later, the Haldeman family set up home in Richardson, Texas.[12] There developed permanent difficulties between Koresh and his stepfather,[13][14] but the boys got on well.[15]

Koresh described his early childhood as lonely.[16] Due to his poor study skills and dyslexia partially caused by poor eyesight, he was put in special education classes and bullied by his schoolmates. Matters improved after about the age of 12, when Koresh became interested in sport, which he was good at, and developed his physique.[17] Despite this turnaround, Koresh dropped out of Garland High School in his junior year. He tried various jobs, but was either fired from or abandoned each of them.

At the age of 19, Koresh had an illegal sexual relationship with a 16-year-old girl, who became pregnant. He never saw the resulting daughter: the teenage mother thought him unfit to be a father, so she moved away and refused to see him.[18] He claimed to have become a born-again Christian in the Southern Baptist Church and soon joined his mother's denomination, the Seventh-day Adventist Church. There, Koresh, then 20, and the pastor's daughter, 15-year-old Sandy Berlin, began a two-year relationship.[19][20] During their courtship, while praying for guidance one day, Koresh allegedly opened his eyes and found the Bible open at Isaiah 34:16, stating that "none should want for her mate".[21] Convinced this was a sign from God, Koresh approached the pastor and told him that God wanted him to have his daughter for a wife; the pastor dismissed the suggestion out of hand and forbade him from ever seeing her again, an instruction that Koresh ignored. With the pastor furious at him and the congregation weary of and repulsed by his sex obsession, Koresh was expelled from the church.[22]

It was now summer 1981, and Koresh's next move was to Waco, Texas, where he joined the Branch Davidians (splinter group of Davidian Seventh-Day Adventist.)[23] Benjamin Roden, who died in 1978,[24] had originated the Branch group in 1955 with new teachings that were not connected with the original Davidians.[citation needed]

Ascent to leadership of the Branch Davidians

[edit]In 1983, Koresh began claiming the gift of prophecy.[citation needed] David Thibodeau, in his 1999 book, A Place Called Waco, speculated that he had a sexual relationship with Lois Roden, the widow of Benjamin Roden and leader of the sect, who was then in her late 60s. Koresh eventually began to claim that God had chosen him to father a child by Lois, who would be the Chosen One.[25] In 1983, Lois allowed Koresh to begin teaching his own message, called "The Serpent's Root", which caused controversy in the group. Lois's son George Roden, intended to be the group's next leader, considered Koresh an interloper.[citation needed]

When Koresh announced that God had instructed him to marry Rachel Jones (who then added Koresh to her name), a period of calm ensued at the Mount Carmel Center, but it proved only temporary. A fire destroyed a $500,000 administration building and press; George Roden said Koresh started the fire, but Koresh replied that "no man set that fire" and that it was a judgment of God.[26] Roden, claiming to have the support of the majority of the sect, forced Koresh and his group off the property at gunpoint. Koresh and around 25 followers set up camp at Palestine, Texas, 90 miles (140 km) from Waco, where they lived under rough conditions in buses and tents for the next two years. During this time, Koresh undertook recruitment of new followers in California, the United Kingdom, Israel, and Australia. That same year, he traveled to Israel, where he claimed he had a vision that he was the modern-day Cyrus.[27]

The founder of the Davidian movement, Victor Houteff, wanted to be God's implement and establish the Davidic kingdom in Israel. Koresh also wanted to be God's tool and set up the Davidic kingdom in Jerusalem. At least until 1990, he believed the place of his martyrdom might be in Israel; however, by 1991, he was convinced that his martyrdom would be in the U.S. instead of in Israel. He said the prophecies of Daniel would be fulfilled in Waco and that the Mount Carmel Center was the Davidic kingdom.[28]

After being exiled to the Palestine camp, Koresh and his followers eked out a primitive existence. When Lois died in 1986, the exiled Branch Davidians wondered if they would ever be able to return to the Mount Carmel Center, but despite the displacement "Koresh now enjoyed the loyalty of the majority of the [Branch Davidian] community".[29] In 1987, George Roden exhumed at least one body from the community cemetery. Roden said he was just moving the cemetery, while Koresh claimed that Roden had issued a challenge to resurrect the body (and that whoever resurrected the body would be the new leader).[26] Koresh went to authorities to file charges against Roden for illegally exhuming a corpse, but was told he would have to show proof (such as a photograph of the corpse).

Koresh seized the opportunity to seek criminal prosecution of Roden by returning to the Mount Carmel Center with seven armed followers, allegedly attempting to get photographic proof of the exhumation. Koresh's group was discovered by Roden, and a gunfight broke out. When the sheriff arrived, Roden had already suffered a minor gunshot wound and was pinned down behind a tree. As a result of the incident, Koresh and his followers were charged with attempted murder. At the trial, Koresh explained that he went to the Mount Carmel Center to uncover evidence of criminal disturbance of a corpse by Roden. Koresh's followers were acquitted, and in Koresh's case, a mistrial was declared.[citation needed]

In 1989, Roden murdered Wayman Dale Adair with an axe blow to the skull after Adair stated his belief that he himself was the true messiah.[30] Roden claimed the man was sent by Koresh to kill him.[31][32] He was judged insane and confined to a psychiatric hospital at Big Spring, Texas. Since Roden owed thousands of dollars in unpaid taxes on the Mount Carmel Center, Koresh and his followers were able to raise the money and reclaim the property. Roden continued to harass the Koresh faction by filing legal papers while imprisoned. When Koresh and his followers reclaimed the Mount Carmel Center, they discovered that tenants who had rented from Roden had left behind a meth lab, which Koresh reported to the local police department and asked to have removed.[33][34]

Koresh was infatuated with American singer Madonna. God, he claimed, had even said to him, "I will give thee Madonna."[35]

Name change

[edit]Vernon Howell filed a petition in California State Superior Court in Pomona on May 15, 1990, to legally change his name "for publicity and business purposes" to David Koresh. On August 28, 1990, Judge Robert Martinez granted the petition.[36]

His first name, David, symbolized a lineage directly to the biblical King David, from whom the new messiah would descend. Koresh (כּוֹרֶשׁ, Koresh) is the Biblical name of Cyrus the Great, a Persian king who is named a messiah for freeing Jews during the Babylonian captivity. By taking the name of David Koresh, he was "professing himself to be the spiritual descendant of King David, a messianic figure carrying out a divinely commissioned errand."[37]

Allegations of child abuse and statutory rape

[edit]Koresh was alleged to have been involved in multiple incidents of physical and sexual abuse of children.[38] His doctrine of the House of David[39] did lead to "marriages" with both married and single women in the Branch Davidians.

A six-month investigation of sexual abuse allegations by the Texas Child Protection Services in 1992 failed to turn up any evidence, possibly because the Branch Davidians concealed the spiritual marriage of Koresh to Rachel's younger sister, Michele, when she was 12, by assigning her a surrogate husband (David Thibodeau, who was 10 years younger than Koresh) for the sake of appearances.[40][41] Regarding the allegations of physical abuse, no evidence was ever found.[clarification needed] In one widely reported incident, ex-members claimed that Koresh became irritated with the cries of his son Cyrus and spanked the child severely for several minutes on three consecutive visits to the child's bedroom. In a second report, a man involved in a custody battle visited the Mount Carmel Center and claimed to have seen the beating of a young boy with a stick.[42]

Finally, the FBI's justification for forcing an end to the 51-day stand-off was predicated on the charge that Koresh was abusing children inside the Mount Carmel Center. Allegations had been made that he had fathered children with underaged girls in the Branch Davidians. In the hours that followed the deadly conflagration, Attorney General Janet Reno told reporters, "We had specific information that babies were being beaten."[43] However, FBI Director William Sessions publicly denied the charge and told reporters that they had no such information about child abuse inside the Mount Carmel Center.[44] A careful examination of the other child abuse charges found the evidence to be weak and ambiguous, casting doubt on the allegations.[45]

The allegations of child abuse largely stem from detractors and ex-members.[46] The 1993 Justice Department report cites allegations of child sexual and physical abuse. Legal scholars[who?] point out that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) had no legal jurisdiction in the matter of child protection, and these accounts appear to have been inserted by the ATF to inflame the case against Koresh.[citation needed] For example, the account of former Branch Davidian Jeannine Bunds is reproduced in an ATF affidavit. She said that Koresh had fathered at least 15 children with various women and girls, and that she had personally delivered seven of these infants. Bunds also says that Koresh would annul all marriages of couples who joined the group and had exclusive sexual access to the women and girls.[47][48] Thibodeau, a student of Koresh and one of the few to escape the fire that destroyed the compound, stated in 2018 that while he considered Koresh a friend, he "certainly was guilty of something. He was either a polygamist or he was guilty of statutory rape. Probably both."[49]

In his book, James Tabor states that on a videotape that was sent out of the compound during the siege, Koresh acknowledged that he had fathered more than 12 children by several "wives".[50] On March 3, 1993, during negotiations to secure the release of the remaining children, Koresh advised hostage negotiators that: "My children are different than those others," referring to his direct lineage versus those children whom he had previously released.[citation needed]

Bruce Perry, the chief of psychiatry at Texas Children's Hospital who led the team that cared for the twenty-one children that survived the siege of the Davidian compound, wrote after a two-month investigation that "the children released from Ranch Apocalypse do not appear to have been victims of sexual abuse."[51] However, while Perry noted that the Children of Waco were not physically abused, he reported that they were "likely exposed to inappropriate concepts of sexuality," and subject to "a whole variety of destructive emotional techniques ... including shame, coercion, fear, intimidation, humiliation, guilt, overt aggression and power."[52] Perry has reiterated this view as late as 2018.[53]

Raid and siege by federal authorities

[edit]

The Waco siege began on February 28, 1993, when the ATF raided Mount Carmel Center. The ensuing gun battle resulted in the deaths of four ATF agents and six Branch Davidians. Shortly after the initial raid, the FBI Hostage Rescue Team took command of the federal operation, because the FBI has jurisdiction over incidents involving the deaths of federal agents. The negotiating team established contact with Koresh inside the compound. Communication over the next 51 days included telephone exchanges with various FBI negotiators.[citation needed]

Koresh himself had been seriously injured by a gunshot. As the standoff continued, he and his closest male associates negotiated delays, so that he could possibly write religious documents, which he said he needed to complete before his surrender. Koresh's conversations with the negotiators were dense and they also included biblical imagery. The FBI negotiators treated the situation as a hostage crisis.[citation needed]

The siege of the Mount Carmel Center ended on April 19, 1993, when U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno approved recommendations of FBI officials to proceed with a final advance in which the Branch Davidians would be removed from the Mount Carmel Center by force. In an attempt to flush Koresh out of the stronghold, the FBI resorted to pumping CS gas into the compound with the aid of an M728 Combat Engineer Vehicle, which was equipped with a battering ram.[54] In the course of the advance, the Mount Carmel Center caught fire under circumstances that remain disputed, with either the Branch Davidians and Koresh himself or the FBI being blamed for having started the fire. Barricaded inside the building, 79 Branch Davidians perished in the ensuing blaze; 21 of these victims were children under the age of 16.[55]

Coroner reports showed many Davidians died from single gunshot wounds to the head – Koresh, then 33, was one of them.[56] A postmortem on his badly burned remains could not determine whether he died by suicide or was killed.[57] One FBI official speculated that Steve Schneider, Koresh's right-hand man, "probably realized that he was dealing with a fraud" and so shot and killed Koresh before turning the gun on himself.[57] The medical examiner reported 20 people, including five children under the age of 14, had been shot, and a three-year-old had been stabbed in the chest.[58]

Legacy

[edit]Koresh is buried at Memorial Park Cemetery, Tyler, Texas, in the "Last Supper" section. Several of his albums were released, including Voice of Fire, in 1994. In 2004, Koresh's 1968 Chevrolet Camaro, which had been damaged during the raid, sold for $37,000 at auction. It is now owned by Ghost Adventures host Zak Bagans.[59]

Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols cited the Waco siege as their motivation for the Oklahoma City bombing of April 19, 1995, which was timed to coincide with the second anniversary of the Waco assault.[60]

Three documentary films have been made about the siege, including different versions of Waco: The Rules of Engagement, Waco: A New Revelation, and Waco: Madman or Messiah. In 2018, BBC Radio 5 Live created a radio podcast titled End of Days, which was about the death and life of Koresh, his involvement in the Waco siege, and the recruitment of people who lived in Nottingham, Manchester, and London into the Branch Davidians. The Court TV (now TruTV) television series Mugshots released an episode about Koresh.[61] A Mexican movie was made entitled "Tragedia en Waco" or "Tragedia: Sucedio en Monte Carmelo Waco Texas", 1993, written by Ulf Kjell Gür.[62] aired by EstrellaTV in April 2021.

Koresh is portrayed by Taylor Kitsch in the 2018 miniseries Waco.[63] However, in the sequel series Waco: The Aftermath he is portrayed by Keean Johnson. He was also one of the sources of inspiration used to create the fictional cult leader Joseph Seed in the 2018 action-adventure video game Far Cry 5.[64] In 2011, British indie rock band The Indelicates released a concept album, David Koresh Superstar, about Koresh and the Waco siege.[65][66] He was also one of the sources of inspiration used to create the fictional cult leader Salem Koresh in the 2021 action-adventure video game Outriders.

A Netflix series called Waco: American Apocalypse, was released in March 2023. The series encompasses three episodes and features real and never before released footage and interviews with surviving cult members and others involved.[67]

See also

[edit]- List of messiah claimants

- List of people claimed to be Jesus

- List of Seventh-day Adventists

- Messiah complex

- Twelve Tribes Communities

Notes

[edit]- ^ England, Mark (September 5, 1993). "12 children killed in fire Howell's, ex-member says". Waco Tribune-Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ Johnstone 2015, p. 83.

- ^ Burton, Tara Isabella (April 19, 2018). "The Waco tragedy, explained". Vox. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Tracey, Ciaran (October 31, 2018). "Why 30 Britons joined the Waco cult". BBC News. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Staff (October 10, 1993). "The Book of Koresh". Newsweek. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ His parents began the marriage process upon learning of the pregnancy, but the ceremony ultimately never took place; each blamed the other for this. See: Samples et al. 1994, p. 18.

- ^ a b Samples et al. 1994, pp. 19–20.

Koresh would not see his father again until he was 17; see: "Portrait Of Koresh Full Of Contradictions – Parents Try To Reconcile Memories As Ex-Followers Paint Other Image". Dallas Morning News. March 2, 1993. Retrieved March 16, 2024. - ^ Samples et al. 1994, p. 20.

Bonnie herself said (Haldeman 2007, pp. 10–11) she moved to Dallas with Roy Haldeman, her future husband, after meeting him when she began working at a bar he part-owned in Houston. - ^ Samples et al. 1994, p. 20.

Bonnie herself said (Haldeman 2007, p. 10) that she gave Koresh to her mother while she was married to Golden, to protect him from the spankings her husband inflicted on him. - ^ Breault & King 1993, pp. 27–8.

- ^ Samples et al. 1994, p. 21.

Koresh said the abuse, which included rape, lasted four years, until he was nine, but afflicted him his whole life. He said he never revealed who the perpetrator was to avoid upsetting his mother. - ^ Haldeman 2007, pp. 12–3

- ^ Samples et al. 1994, p. 27

- ^ Haldeman 2007, p. 12

- ^ Haldeman 2007, pp. 14–6.

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. ???.

- ^ Breault & King 1993, p. 31.

- ^ Breault & King 1993, p. 33.

- ^ "The Pop Life". The New York Times. March 25, 1994. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "'Recordings for Deviants': interview of Sandy Berlin". Vice. 1995. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Breault & King 1993, pp. 34–5.

- ^ Breault & King 1993, p. 35.

- ^ Beck 2024, p. 36.

- ^ Breault & King 1993, p. 38.

- ^ Wilson 2000.

- ^ a b "Crying in the wilderness: A religious commune sets up a dwelling place in the woods amid a struggle between rival prophets". January 17, 1988.

- ^ McEvoy, Colin (March 27, 2023). "David Koresh: Leader of the Branch Davidians". Biography. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ Valentine, Carol A. (2001), David Koresh and The Cuckoo's Egg – pt. 3, archived from the original on April 26, 2007, retrieved September 7, 2006

- ^ David G. Bromley and Edward D. Silver, "The Davidian Tradition: From Patronal Clan to Prophetic Movement," p.54 in Stuart A. Wright, Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1995)

- ^ Marc Breault and Martin King, Inside the Cult, Signet, 1st Printing June 1993. ISBN 978-0-451-18029-2. (Australian edition entitled Preacher of Death).

- ^ Verhovek, Sam Howe (December 6, 1994). "A Fight in Texas for the Homeland of a Sect". The New York Times.

- ^ Pitts, William L. "Davidians and Branch Davidians". Handbook of Texas – Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ Thibodeau, David (1999), The truth about Waco, archived from the original on April 28, 2001

- ^ Thomas R. Lujan, "Legal Aspects of Domestic Employment of the Army", Parameters US Army War College Quarterly, Autumn 1997, Vol. XXVII, No. 3.

- ^ Breault & King 1993, p. 112.

- ^ Clifford L. Linedecker, Massacre at Waco, Texas, St. Martin's Press, 1993, page 94. ISBN 0-312-95226-0.

- ^ Bromley and Silver, p.57

- ^ See Christopher G. Ellison and John Bartkowski, "'Babies Were Being Beaten': Exploring Child Abuse Allegations at Ranch Apocalypse," pp.111–152 in Stuart A. Wright (ed.), Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1995)

- ^ See Bromley and Silver, pp.60–65

- ^ David Thibodeau and Leon Whiteson, A Place Called Waco: A Survivor's Story (New York: Public Affairs, 1999)

- ^ Bryce, Robert (November 12, 1999). "Salvation: Former Davidian Tells Survivor's Story". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved November 29, 2024.

- ^ Ellison and Bartkowski, 120–121.

- ^ Sam Howe Verovek, "In Shadow of Texas Siege, Uncertainty for Innocents." New York Times, 1993, March 8

- ^ Stephen Labaton, "Confusion Abounds in the Capital on Rationale for Assault on Cult," New York Times, 1993, April 21

- ^ Ellison and Bartkowski, 1995

- ^ John R. Hall, "Public Narratives and the Apocalyptic Sect," pp.205–235 in Stuart A. Wright (ed.), Armageddon in Waco (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1995); Stuart A. Wright, "Construction and Escalation of a 'Cult' Threat: Dissecting Moral Panic and Official Reaction to the Branch Davidians," pp.75–94 in Stuart A. Wright (ed.), Armageddon in Waco

- ^ U.S. Department of Justice (1993), "Evidence of Historical Child Sexual and Physical Abuse", Report to the Deputy Attorney General on the Events at Waco, Texas February 28 to April 19, 1993 (From ATF Affidavit in Support of Arrest of Koresh, taken from ATF Special Agent Aguilera's interview of former compound resident Jeannine Bunds, included in Agent Aguilera's affidavit in support of the Koresh arrest warrant "Davy Aguilera, Special Agent Bureau of ATF, Subscribed and sworn to before me this 25th day of February 1993 Dennis G. Green United States Magistrate Judge Western District of Texas – Waco" (Redacted ed.), Washington, D.C.: U.S.DoJ, archived from the original on January 24, 2007, retrieved February 4, 2007

- ^ Ellison and Bartkowski, 1995; Wright, "Construction and Escalation of a 'Cult' Threat," 1995

- ^ Skinner, Paige. "Waco Siege Survivor Behind New Miniseries Tells Us What TV Has Gotten Wrong". Dallas Observer. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ Tabor, James D.; Gallagher, Eugene V. (1997), Why Waco?: Cults & the Battle for Religious Freedom in America, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20899-5

- ^ Boyer, Peter J. (May 15, 1995). ""The Children of Waco"". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Rimer, Sarah (May 4, 1993). "Growing Up Under Koresh: Cult Children Tell of Abuses". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Wilking, Spencer (January 4, 2018). "Branch Davidian children's drawings foretold deadly Waco fire, psychiatrist says". ABC News. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Remembering Waco and the Branch Davidian Church 20 years later". Liberty Under Fire. April 30, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about Waco". Frontline/PBS. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ Samples et al. 1994, pp. 15–6.

- ^ a b "Koresh's Top Aide Killed Cult Leader, FBI Official Says". The Washington Post. September 4, 1993. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "Autopsies: Children At Waco Were Shot". The Washington Post. July 4, 2000. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Hart, Lianne (September 26, 2004). "Puny market for avid Koresh's pride and joy fails to excite many bidders". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Michel, Herbeck, Lou, Dan (April 19, 2020). "How Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh changed the fringe right". Buffalo News.com. Buffalo News. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "MUGSHOTS: David Koresh". FilmRise. December 1, 2013. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ "Tragedia en Waco, Texas (1993) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ Pedersen, Erik (August 30, 2016). "Michael Shannon & Taylor Kitsch Topline Weinstein Co. Series 'Waco', Based on 1993 Siege". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (March 2, 2018). "Far Cry 5 cult adviser reveals how these fanatics thrive: Follow the money". VentureBeat. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ Mayer Nissim (January 4, 2011). "Indelicates announce 'imminent' new album". Digital Spy. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "The Indelicates: David Koresh Superstar". PopMatters. May 21, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Netflix's Trailer for 'Waco: American Apocolypse' is Terrifying and Sobering". ihorror. March 23, 2023.

References

[edit]- Beck, Richard (2024). "I will give thee Madonna". London Review of Books. 46 (6): 35–36.

- Breault, Marc; King, Martin (1993). Inside the Cult. New York, NY: Signet. ISBN 978-0-451-18029-2.

- Haldeman, Bonnie (2007). Memories of the Branch Davidians: The Autobiography of David Koresh's Mother. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-932-79298-0.

- Johnstone, Ronald L. (2015). Religion in Society: A Sociology of Religion. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34454-4.

- Rifkind, L. J.; Harper, L. F. (1994). "The Branch Davidians and the Politics of Power and Intimidation". Journal of American Culture. 17 (4): 65–72. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1994.t01-2-00065.x.

- Samples, Kenneth R.; de Castro, Erwin M.; Abanes, Richard; Lyle, Robert J. (1994). Prophets of the Apocalypse: David Koresh & Other American Messiahs. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. ISBN 0-8010-8367-2.

- Wilson, Colin (2000). The Devil's Party: A History of Charlatan Messiahs. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-852-27843-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Cook, Kevin (2024). Waco Rising: David Koresh, the FBI, and the Birth of America's Modern Militias. New York, NY: Holt. ISBN 978-1-250-84051-6.

- Guinn, Jeff (2023). Waco: David Koresh, the Branch Davidians, and a Legacy of Rage. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-982-18610-4.

- Lewis, J. R. (ed.), From the Ashes: Making sense of Waco (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1994).

- Newport, Kenneth G. C. The Branch Davidians of Waco: The History and Beliefs of an Apocalyptic Sect (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Reavis, Dick J. The Ashes of Waco: An Investigation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995). ISBN 0-684-81132-4

- Shaw, B. D., "State Intervention and Holy Violence: Timgad/Paleostrovsk/Waco," Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 77,4 (2009), 853–894.

- Tabor, James; Gallagher, Eugene (1995). Why Waco? Cults and the battle for religious freedom in America. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20186-6.

- Talty, Stephan (2023). Koresh: The True Story of David Koresh and the Tragedy at Waco. London: Apollo. ISBN 978-1-801-10267-4.

- Wright, Stuart A., ed. (1995). Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

External links

[edit]- "Vernon Wayne Howell aka David Koresh". Branch Davidians Religious Leader. Find a Grave. July 16, 2002.

- 1959 births

- 1993 deaths

- 20th-century apocalypticists

- American conspiracy theorists

- American former Protestants

- American religious leaders

- American shooting survivors

- Branch Davidians

- Child marriage in the United States

- Christian conspiracy theorists

- Christian messianism

- Crimes in religion

- Deaths by firearm in Texas

- Founders of new religious movements

- Garland High School alumni

- People with dyslexia

- People disfellowshipped by the Seventh-day Adventist Church

- People from Garland, Texas

- People from Houston

- People from Waco, Texas

- Polygamy in the United States

- Prophets in Christianity

- Religious scandals

- Waco siege