Bogatyr

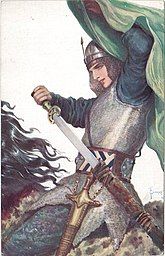

A bogatyr (Russian: богатырь, IPA: [bəɡɐˈtɨrʲ] ⓘ, Ukrainian: богатир, IPA: [boɦɑˈtɪr] ⓘ) or vityaz (Russian: витязь, IPA: [ˈvʲitʲɪsʲ] ⓘ, Ukrainian: витязь, IPA: [ˈʋɪtʲəzʲ]) is a stock character in medieval East Slavic legends, akin to a Western European knight-errant. Bogatyrs appear mainly in Rus' epic poems—bylinas. Historically, they came into existence during the reign of Vladimir the Great (Grand Prince of Kiev from 978 to 1015) as part of his elite warriors (druzhina[1]), akin to Knights of the Round Table.[2] Tradition describes bogatyrs as warriors of immense strength, courage and bravery, rarely using magic while fighting enemies[2] in order to maintain the "loosely based on historical fact" aspect of bylinas. They are characterized as having resounding voices, with patriotic and religious pursuits, defending Rus' from foreign enemies (especially nomadic Turkic steppe-peoples or Finno-Ugric tribes in the period prior to the Mongol invasions) and their religion.[3]

Etymology

[edit]

The word bogatyr is not of Slavic origin.[4] It derives from the Turco-Mongolic baghatur "hero", which is itself of uncertain origin. The term is recorded from at least the 8th century.[5]

Gerard Clauson suggests that bağatur was in origin a Hunnic proper name, specifically that of Modu Chanyu.[6] Alternatively, a suggestion cited in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary that the term may be related to the Sanskrit bhagadhara.[7]

Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (1890—1907) claims that the first known use of the word in a Kievan context occurred in Stanisław Sarnicki's 1585 book Descriptio veteris et novae Poloniae cum divisione ejusdem veteri et nova (A description of the Old and the New Poland with the old, and a new division of the same), which states: "Rossi ... de heroibus suis, quos Bohatiros id est semideos vocant, aliis persuadere conantur."[7] ("Ruthenians ... try to convince others about their heroes whom they call Bogatirs, meaning demigods.")

The term vityaz comes from Proto-Slavic *vitędzь, from Proto-Germanic *wīkingaz through a West Germanic intermediary. The earliest attested form is Old English wicing, "pirate", whence modern English viking. This in turn probably comes from Latin vicus with the Germanic suffix *-inga-, indicating belonging. In Germanic and Latin sources, the word has negative connotations. The circumstances of borrowing, and how it came to mean "hero" in Slavic, remain unclear.[8] Alternatively, per Brückner and Machek, the Proto-Slavic term could be of native Slavic origin, "victory" or "trophy".

In modern Russian, the word bogatyr also labels a courageous hero, an athlete or a physically strong man.[9]

Overview

[edit]

Many Rus epic poems, called bylinas (Ukrainian: билини; Russian: былины), prominently featured stories about these heroes, as did several chronicles, including the 13th century Galician–Volhynian Chronicle. Some bogatyrs are presumed to be historical figures, while others, like the giant Svyatogor, are purely fictional and possibly echo figures in Slavic pagan mythology. Some scholars divide the epic poems into three collections: the Mythological epics, older stories that were told before Kiev-Rus was founded and Christianity was brought to the region, and included magic and the supernatural; the Kievan cycle, which contains the largest number of bogatyrs and their stories (Ilya Muromets, Dobrynya Nikitich, and Alyosha Popovich); and the Novgorod cycle, focused on Sadko and Vasily Buslayev, which depicts everyday life in Novgorod.[10][need quotation to verify]

Many of the stories about bogatyrs revolve around the court of Vladimir I of Kiev and feature in the Kievan Cycle. The most notable bogatyrs or vityazes served at his court: the trio of Alyosha Popovich, Dobrynya Nikitich and Ilya Muromets. Each of them tends to be known for a certain character trait: Alyosha Popovich for his wits, Dobrynya Nikitich for his courage, and Ilya Muromets for his physical and spiritual power and integrity, and for his dedication to the protection of his homeland and people. Most of those bogatyrs' adventures are fictional, and often included fighting dragons, giants and other mythical creatures. However, the bogatyrs themselves were often based on real people. Historical prototypes exist both for Dobrynya Nikitich (the warlord Dobrynya) and for Ilya Muromets.

The Novgorod Republic produced a specific kind of hero, an adventurer rather than a noble warrior. The most prominent examples were Sadko and Vasily Buslayev, who became part of the Novgorod Cycle of folk epics.[10]

The most prominent heroes in these epics are Svyatogor and Volkh Vseslavyevich; they are commonly called the "elder bogatyrs".[citation needed]

Later notable bogatyrs also include those who fought alongside Alexander Nevsky (1221–1263) – including Vasily Buslayev – and those who fought in the 1380 Battle of Kulikovo.

Kievan bogatyrs and their heroic tales have influenced figures in Russian literature and art, such Alexander Pushkin, who wrote the 1820 epic fairy-tale poem Ruslan and Ludmila, Viktor Vasnetsov, and Andrei Ryabushkin whose artworks depict many bogatyrs from the different cycles of folk epics. Bogatyrs are also mentioned in wonder tales in a more playful light as in "Foma Berennikov",[11] a story in Aleksandr Afanas'ev's collection Russian Fairy Tales featuring Alyosha Popovich and Ilya Muromets.

Red Medusa Animation Studio,[12] based in Russia, created an animated parody of the bogatyrs called "Three Russian Bogaturs", in which the titular characters—strong and tenacious, but not overly bright—prevail against various opponents from fairy tales, pop culture, and modern life.[13]

Female bogatyr

[edit]

Though not as heavily researched, the female bogatyr or polianitsa (поляница) is a female warrior akin to the Amazons. Many of the more well-known polianitsas are wives to the famous male bogatyrs, such as Nastas'ya Nikulichna,[14] the wife of Dobrynya Nikitich. While the female bogatyr doesn't quite match the men in strength and bravery, there are stories detailing instances where they save their husbands and outwit the enemy.[14] They are often seen working with the heroes in tales that mention their presence.

Famous bogatyrs

[edit]Most bogatyrs are fictional, but are believed to be based on historical prototypes:

- The three ones below are collectively known as "the three bogatyrs";

- Ilya Muromets, regarded as the greatest of the bogatyrs, from Morivsk or Muromets[15]

- Dobrynya Nikitich – based on a historical warlord of Vladimir I, associated with Nyzkynychi[16]

- Alyosha Popovich ("Alyosha the Priest's Son") – from Pyriatin,[17] a trickster among bogatyrs who is best known for his wits.

- In Russian versions, they are from Murom,[18] Ryazan[19] and Rostov[20] correspondingly

- Mykyta Kozhumyaka, bogatyr and a folk hero snake wrestler, in honor of which Pereyaslav was named

- Evpaty Kolovrat, bogatyr described in The Tale of the Destruction of Ryazan, he fought an army of the Mongol ruler Batu Khan

- Svyatogor, a giant knight who bequeathed his strength to Ilya Muromets (purely fictional)

- Vasily Buslayev of Novgorod

- Anika the Warrior

- Duke Stepanovich

- Dunay Ivanovich

- Volga Svyatoslavovich (possibly based on Oleg of Novgorod or Vseslav of Polotsk[21])

- Sukhman The Bogatyr

- Mikula Selyaninovich ("Mikula the Villager's Son")

Some of the historical warriors also entered folklore and became known as bogatyrs:

- Gavrila Aleksich of Novgorod, who served Alexander Nevsky in Battle of Neva (historical)

- Ratmir of Novgorod, who served Alexander Nevsky in Battle of Neva (historical)

- Peresvet, who sacrificed himself against the Tatars at the Battle of Kulikovo (historical)

Bogatyrs in films

[edit]- Films by Alexander Ptushko:

- Sadko (Садко, 1953)

- Ilya Muromets (Илья Муромец, 1956)

- Ruslan and Ludmila (Руслан и Людмила, 1972), based on a fantasy poem of the same name by Alexander Pushkin.

- Soyuzmultfilm animated films (directed by Ivan Aksenchuk):

- Melnitsa Animation series The Three Bogatyrs:

- Alyosha Popovich and Tugarin the Serpent (Алёша Попович и Тугарин Змей, 2004)

- Dobrynya Nikitich and Zmey Gorynych (Добрыня Никитич и Змей Горыныч, 2006)

- Ilya Muromets and Nightingale the Robber (Илья Муромец и Соловей-Разбойник, 2007)

- The Three Bogatyrs and Shamakhan Queen (Три богатыря и Шамаханская царица, 2010)

- The Three Bogatyrs on Distant Shores (Три богатыря на дальних берегах, 2012)

- The Three Bogatyrs: Course of the horse (Три богатыря: Ход конём)

- The Three Bogatyrs and the Sea King (Три богатыря и Морской царь)

- Other films:

- The Dragon Spell (Микита Кожум'яка, 2016) is a 2016 Ukrainian 3D animated fantasy film directed by Manuk Depoyan based on Anton Siyanika's fairy tale of the same name.

- Mykyta Kozhumyaka (1965) animated Ukrainian cartoon based on folk tales from the times of Kievan Rus'

- Alexander Nevsky (Александр Невский, 1938) by Sergei Eisenstein. Although based on real history, the film also shows a strong bylina influence and features bylina bogatyr Vasily Buslayev as a secondary character.

- The Battle of Kerzhenets (1971)

- Vasilisa Mikulishna (1975, by Roman Davydov), an animated adaptation of a bylina of the same name.

- Prince Vladimir (Князь Владимир, 2006) also combines real medieval history with fantasy and folklore.

- Last Knight (2017), a comedy film that deconstructs Russian folklore.

See also

[edit]- Baghatur

- Knight-errant

- Slavic mythology

- The Bogatyr Gates, a movement from Mussorgsky's piano suite "Pictures at an Exhibition".

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^

Pronin, Alexander (1719). Byliny; Heroic Tales of Old Russia. Possev. p. 26. ISBN 9783791219882. Retrieved 2019-01-05.

Stay in my druzhina and be my senior bogatyr, chief above all the others.

- ^ a b Bailey, James; Ivanova, Tatyana (1998). An Anthology of Russian Folk Epics. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- ^ "Богатыри". www.vehi.net. Archived from the original on 2013-02-06. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- ^ Translators, interpreters, and cultural negotiators : mediating and communicating power from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era. Federici, Federico M.,, Tessicini, Dario. New York, NY. 2014-11-20. ISBN 9781137400048. OCLC 883902988.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ C. Fleischer, "Bahādor", in Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Sir Gerard Clauson (1972). An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth-Century Turkish. pp. 301–400.

- ^ a b ""Богатыри", Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона". vehi.net. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- ^ Saskia Pronk-Tiethoff, The Germanic Loanwords in Proto-Slavic (Brill, 2013), pp. 96–98. Based on her PhD diss.

- ^ Translators, interpreters, and cultural negotiators : mediating and communicating power from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era. Federici, Federico M.,, Tessicini, Dario. New York, NY. 2014-11-20. ISBN 9781137400048. OCLC 883902988.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Bailey, James; Ivanova, Tatyana (1998). An Anthology of Russian Folk Epics. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- ^ Afanasyev, A.N.; Guterman, Norbert; Jakobson, Roman; Alexeieff, Alexandre (2006). Russian fairy tales. [New York]. ISBN 0394730909. OCLC 166025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Red Medusa".

- ^ About Three Russian Bogaturs, YouTube.com. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ a b Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian & Slavic myth and legend. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576070638. OCLC 39157488.

- ^ Ukrainian bylyny: Historical and literary edition of the East Slavic epic.// Arrangement, preface, afterword, notes and treatment of Ukrainian folk tales and legends on ancient themes by V. Shevchuk; Drawings by B. Mykhaylov. Kyiv: Veselka. 2003. 247 pages (In Ukrainian)

- ^ "On the maternal kinship of St. Vladimir", in "Notes of the Imperial Academy of Sciences", V. Archive of the original for July 1, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2012. (In Russian)

- ^ Y. I. Dzira. South Ruthenian primer // Encyclopedia of the history of Ukraine: in 10 volumes / edited by: V. A. Smoliy (head) and others. ; Institute of the History of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. — K. : Naukova Dumka, 2003. — Vol. 1: A — V. — P. 394. — ISBN 966-00-0734-5 .

- ^ James Bailey; Tatyana Ivanova (2015). An Anthology of Russian Folk Epics. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-873-32641-4.

- ^ James Bailey; Tatyana Ivanova (2015). An Anthology of Russian Folk Epics. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-873-32641-4.

- ^ James Bailey; Tatyana Ivanova (2015). An Anthology of Russian Folk Epics. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-873-32641-4.

- ^ Всеслав Брячиславич // Биографический справочник — Мн.: «Белорусская советская энциклопедия» им. Петруся Бровки, 1982. — Т. 5. — С. 129. — 737 с.

Sources

[edit]- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691135892. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Богатыри и витязи Русской земли: По былинам, сказаниям и песням. (1990) Moscow: "Moskovsky Rabochy" publishers (in Russian)

- Ivanova, T. G., and James Bailey. An Anthology of Russian Folk Epics. Braille Jymico Inc., 2006.