Body Heat

| Body Heat | |

|---|---|

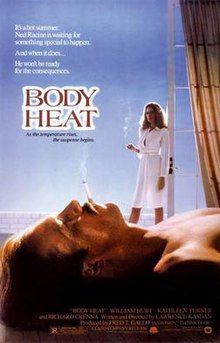

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Lawrence Kasdan |

| Written by | Lawrence Kasdan |

| Produced by | Fred T. Gallo Robert Grand |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Richard H. Kline |

| Edited by | Carol Littleton |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $9 million |

| Box office | $24 million |

Body Heat is a 1981 American neo-noir[1][2] erotic thriller film written and directed by Lawrence Kasdan in his directorial debut. It stars William Hurt and Kathleen Turner, featuring Richard Crenna, Ted Danson, J. A. Preston and Mickey Rourke. The film was inspired by the classic film noir Double Indemnity (1944), in turn based on the 1943 novel of the same name.

The film launched Turner's career—Empire magazine cited the film in 1995 when it named her one of the "100 Sexiest Stars in Film History".[3] The New York Times wrote in 2005 that, propelled by her "jaw-dropping movie debut [in] Body Heat ... she built a career on adventurousness and frank sexuality born of robust physicality".[4]

Plot

[edit]In South Florida, womanizing low-rent lawyer Ned Racine begins an affair with Matty Walker, the beautiful young wife of shady businessman Edmund Walker. The affair quickly becomes a consuming passion, but the two take care to keep it secret. Matty tells Ned that she wants a divorce, but a prenuptial agreement would leave her without Edmund's fortune. When she wishes Edmund dead, Ned suggests murdering him. Matty says she wants to forge a new will, but Ned warns her that would attract suspicion.

By chance, Ned runs into Matty and Edmund at a restaurant. Matty introduces Ned as a lawyer who has been asking about buying the Walkers' house. The three have dinner, during which Edmund states he would kill any man who was having an affair with his wife.

Ned meets an old client, bombmaker Teddy Lewis, who builds him an incendiary device. Ned fabricates an alibi by traveling to Miami, where he checks into a hotel and then drives back home in the night. After Ned kills Edmund, he and Matty move the body to an abandoned building that Edmund owns. Ned sets the bomb to destroy Edmund's body and mislead the police. Ned and Matty then part and agree to have no contact until Matty takes possession of the estate.

Soon after, Edmund's lawyer calls Ned about Edmund's new will, which had supposedly been drafted by Ned; the will was supposedly witnessed by Mary Ann Simpson, a woman Ned once met in passing but who is nowhere to be found. The new will has been improperly prepared, violating the rule against perpetuities, and the local judge, with a poor opinion of Ned, nullifies it, leaving Matty the sole beneficiary. Ned realizes Matty has disregarded his warning and forged the will, calculating it would be nullified. Matty pleads for forgiveness, pledging her love for Ned.

The case is investigated by Ned's friends, prosecutor Peter Lowenstein and detective Oscar Grace. They suspect Matty is involved in her husband's death and warn Ned against seeing her; Ned begins openly dating Matty to throw them off. The police deduce Edmund was not killed at the arson scene because his glasses were missing. Also, Matty appears to have lied about Simpson. Oscar begins to suspect Ned when he realizes Ned's alibi in Miami does not hold. Edmund's niece, who once caught Matty and Ned having sex, is brought to the police but does not recognize Ned.

Increasingly nervous and questioning Matty's loyalty, Ned happens upon an acquaintance who says he had recommended Ned to Matty. Later, Teddy tells Ned about a woman who wanted to know how to rig a bomb to a door. Matty calls Ned, saying her maid had agreed to return the incriminating glasses after she paid her off. She asks Ned to pick up the glasses from her boathouse. There, Ned spots a wire attached to the door. Matty arrives, and Ned asks her to get the glasses instead. Oscar arrives and observes their interaction. Matty walks toward the boathouse, which then explodes. A body found inside is identified from dental records as Matty's.

Now in prison, Ned tries to convince Oscar that "Matty" is still alive, believing that she had assumed the real Matty's identity to conceal her past from Edmund. Ned surmises the "Mary Ann Simpson" that Ned previously met had discovered the scheme and was blackmailing Matty, only to be murdered, her body planted in the boathouse. Had Ned been killed in the explosion, the police would have found both suspects' bodies and closed the case. Oscar is not convinced and reminds Ned that he actually did kill Edmund.

Ned obtains a copy of Matty's high school yearbook: in it are photos of Mary Ann Simpson and Matty Tyler, confirming his suspicion. Below Mary Ann's photo is the nickname "The Vamp" and "Ambition—To be rich and live in an exotic land". The real Mary Ann is seen lounging on a tropical beach living a new life.

Cast

[edit]- William Hurt as Ned Racine

- Kathleen Turner as Matty Walker

- Richard Crenna as Edmund Walker

- Ted Danson as Peter Lowenstein

- J. A. Preston as Oscar Grace

- Mickey Rourke as Teddy Lewis

- Jane Hallaren as Stella

- Lanna Saunders as Roz Kraft

- Michael Ryan as Miles Hardin

- Larry Marko as Judge Costanza

- Kim Zimmer as Mary Ann

- Deborah Lucchesi as Beverly

- Lynn Hallowell as Angela

- Thom J. Sharp as Michael Glenn

In addition, the director's wife, Meg Kasdan, has a brief cameo as one of Racine's sexual partners – a nurse seen getting ready to leave his apartment.

Production

[edit]Kasdan "wanted this film to have the intricate structure of a dream, the density of a good novel, and the texture of recognizable people in extraordinary circumstances."[5] George Lucas acted as uncredited executive producer following successful collaborations with Kasdan as a scriptwriter on Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Empire Strikes Back.[6] Christopher Reeve turned down the role of Ned Racine, which eventually went to his friend, William Hurt; Reeve would later regret the decision, though he was "glad for" his friend.[7] Gail Matthius from Saturday Night Live auditioned for Turner's role.[8]

A substantial portion of the film was shot in east-central Palm Beach County, Florida, including downtown Lake Worth and in the oceanside enclave of Manalapan. Additional scenes were shot on Hollywood Beach, Florida, such as the scene set in a band shell.

There was originally more graphic and extensive sex scene footage, but this was shown only in an early premiere, including in West Palm Beach, the area where it was filmed, and was later edited out for wider distribution. In an interview, Body Heat film editor Carol Littleton says, "Obviously, there was more graphic footage. But we felt that less was more."

Music

[edit]In late 1980, Lawrence Kasdan met with four composers whose works he had admired, but only John Barry presented ideas which were close to the director's own. 10 demos were recorded on March 31 and Barry wrote the whole score during April and early May 1981. The composer provided several themes and leitmotifs—the most memorable was "Main Theme", heard during the main titles and representing Matty.[9]

Barry worked closely with recording sessions engineer Dan Wallin to mix the soundtrack album, but for several reasons J.S Lasher (who produced the limited-edition LP and CD) remixed multitracks himself without Barry's or Wallin's participation.[10]

J.S Lasher's album was released several times: as a 45 RPM (Southern Cross LXSE 1.002) in 1983 and as a CD (Label X LXCD 2) in 1989. Both editions also included 'Ladd Company Logo' composed and conducted by John Williams.

In 1998, Varèse Sarabande released a re-recording by Joel McNeely and the London Symphony Orchestra. This CD contained several new tracks (versus J.S Lasher's editions), but still was not complete.

In August 2012, Film Score Monthly released a definitive two-disc edition: the complete score with alternate, unused, and source cues on disc 1, and the original, Barry-authorized album and theme demos on disc 2.[11]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Body Heat was a commercial success. In the United States and Canada, it grossed $24.1 million at the box office,[12] against a budget of $9 million.[13]

Critical response

[edit]Upon its release, Richard Corliss wrote "Body Heat has more narrative drive, character congestion and sense of place than any original screenplay since Chinatown, yet it leaves room for some splendid young actors to breathe, to collaborate in creating the film's texture"; it is "full of meaty characters and pungent performances—Ted Danson as a tap-dancing prosecutor, J.A. Preston as a dogged detective, and especially Mickey Rourke as a savvy young ex-con who looks and acts as if he could be Ned's sleazier twin brother."[5] Variety magazine wrote "Body Heat is an engrossing, mightily stylish meller in which sex and crime walk hand-in-hand down the path to tragedy, just like in the old days. Working in the imposing shadow of the late James M. Cain, screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan makes an impressively confident directorial debut".[14] Roger Ebert included the film on his "10 Best List" for the year.[15]

Janet Maslin wrote that Body Heat was "skillfully, though slavishly, derived" from 1940s film noir classics; she stated that, "Mr. Hurt does a wonderful job of bringing Ned to life," but was not impressed by Turner's performance:

Sex is all-important to Body Heat, as its title may indicate. And beyond that there isn't much to move the story along or to draw these characters together. A great deal of the distance between [Ned and Matty] can be attributed to the performance of Miss Turner, who looks like the quintessential forties siren, but sounds like the soap-opera actress she is. Miss Turner keeps her chin high in the air, speaks in a perfect monotone, and never seems to move from the position in which Mr. Kasdan has left her.[16]

Pauline Kael dismissed the film, citing its "insinuating, hotted-up dialogue that it would be fun to hoot at if only the hushed, sleepwalking manner of the film didn't make you cringe or yawn".[17] Ebert responded to Kael's negative review when he added the film to his "Great Movies" list:

Yes, Lawrence Kasdan's Body Heat (1981) is aware of the films that inspired it—especially Billy Wilder's Double Indemnity (1944). But it has a power that transcends its sources. It exploits the personal style of its stars to insinuate itself; Kael is unfair to Turner, who in her debut role played a woman so sexually confident that we can believe her lover (William Hurt) could be dazed into doing almost anything for her. The moment we believe that, the movie stops being an exercise and starts working.[18]

John Simon of National Review described Body Heat as 'derivative and odious'.[19]

In a home video review for Turner Classic Movies, Glenn Erickson called it "arguably the first conscious Neo Noir"; he wrote "Too often described as a quickie remake of Double Indemnity, Body Heat is more detailed in structure and more pessimistic about human nature. The noir hero for the Reagan years is ...more like the self-defeating Al Roberts of Edgar Ulmer's Detour".[20] Body Heat received mostly positive reviews from critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a 96% approval rating based on 47 reviews, and an average rating of 8.10/10. The site's consensus states, "Made from classic noir ingredients and flavored with a heaping helping of steamy modern spice, Body Heat more than lives up to its evocative title."[21] On Metacritic, the film holds a weighted average score of 77 out of 100 based on 11 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[22]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – No. 92[23]

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – No. 94[24]

Rourke earned critical acclaim for his performance, which helped him evolve from character actor to movie star.[25]

Home media

[edit]Warner Bros. released a 25th-anniversary Deluxe Edition DVD of Body Heat, including a documentary about the film by Laurent Bouzereau, a "number of rightfully deleted scenes",[20] and a trailer.

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth; eds. (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd ed.). Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5

- ^ Schwartz, Ronald (2005). Neo-noir: The New Film Noir Style from Psycho to Collateral. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8108-5676-9.

- ^ "The 100 Sexiest Movie Stars: The Women". Empire. 1995. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-20. Alt URL

- ^ Green, Jesse (March 20, 2005). "Kathleen Turner Meets Her Monster". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ^ a b Corliss, Richard (August 24, 1981). "Torrid Movie, Hot New Star". Time. Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ^ "Body Heat". July 20, 1997. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Christopher Reeve". The Washington Post. 1985-03-24. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ^ "Andy Hoglund interview with Gail Matthius". Vulture. 2024-06-06. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

- ^ Jon Burlingame, liner notes from Film Score Monthly's Body Heat CD (FSM Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 4, 6-7)

- ^ Jon Burlingame, liner notes from Film Score Monthly's Body Heat CD (FSM Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 13-14)

- ^ "Body Heat". Film Score Monthly. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ "Body Heat". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "The Unstoppables". Spy. Nov 1988. p. 94. ISSN 0890-1759. Retrieved 2023-10-12 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Body Heat". Variety. December 31, 1980. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 15, 2004). "Ebert's 10 Best Lists: 1967-present". rogerebert.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (August 28, 1981). "Body Heat". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (December 9, 2005). "An appeal powered by steam". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 20, 1997). "Body Heat (1981)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Simon, John (2005). John Simon on Film: Criticism 1982-2001. Lanham, Maryland: Applause Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-1557835079.

- ^ a b Erickson, Glenn (2006). "Body Heat (Special Edition): Home Video Review". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ^ "Body Heat". Rotten Tomatoes. San Francisco, California: Fandango Media. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Body Heat Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (March 15, 2020). "My Top Ten Bit Parts in Films". Filmink.

External links

[edit]- Body Heat at IMDb

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› Body Heat at AllMovie

- Body Heat at Rotten Tomatoes

- Body Heat at Box Office Mojo

- Body Heat at Metacritic

- 1981 films

- 1980s erotic thriller films

- 1980s mystery thriller films

- American erotic thriller films

- American mystery thriller films

- American neo-noir films

- 1980s English-language films

- Erotic mystery films

- Films about adultery in the United States

- Films about sexuality

- Films directed by Lawrence Kasdan

- Films scored by John Barry (composer)

- Films set in Florida

- Films shot in Florida

- Films shot in Hawaii

- The Ladd Company films

- Warner Bros. films

- 1981 directorial debut films

- 1980s American films

- Double Indemnity

- Films with screenplays by Lawrence Kasdan

- English-language mystery thriller films

- English-language erotic thriller films