Bay of Kotor

Bay of Kotor

Boka kotorska Бока которска | |

|---|---|

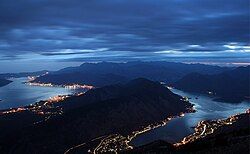

View over Bay of Kotor | |

Budva Municipality, historically considered a part of the Bay of Kotor region. | |

| Coordinates: 42°27′N 18°40′E / 42.45°N 18.67°E | |

| Country | |

| Historical region | |

| Municipalities | Kotor, Herceg Novi, Tivat |

| Area | |

• Total | 616 km2 (238 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Total | 67,496 |

| Demonym(s) | Bokelj (masculine) Bokeljka (feminine) |

| Official name | Natural and Culturo-Historical Region of Kotor |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 125 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Area | 14,600 ha |

| Buffer zone | 36,491 ha |

The Bay of Kotor (Serbo-Croatian: Boka kotorska / Бока которска, Italian: Bocche di Cattaro), also known as the Boka,[1] is a winding bay of the Adriatic Sea in southwestern Montenegro and the region of Montenegro concentrated around the bay. It is also the southernmost part of the historical region of Dalmatia. At the entrance to the Bay there is Prevlaka, a small peninsula in southern Croatia. The bay has been inhabited since antiquity. Its well-preserved medieval towns of Kotor, Risan, Tivat, Perast, Prčanj and Herceg Novi, along with their natural surroundings, are major tourist attractions. The Natural and Culturo-Historical Region of Kotor was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. Its numerous Orthodox and Catholic churches and monasteries attract numerous religious pilgrims and other visitors.

Geography

[edit]

The bay is about 28 kilometres (17 mi) long with a shoreline extending 107.3 kilometres (66.7 mi). It is surrounded by two massifs of the Dinaric Alps: the Orjen mountains to the west, and the Lovćen mountains to the east. The narrowest section of the bay, the 2,300-metre (7,500 ft) long Verige Strait, is only 340 metres (1,120 ft) wide at its narrowest point.[2] The bay is a ria of the vanished Bokelj River, which used to flow from the high mountain plateaus of Mount Orjen.

The bay is composed of several smaller broad bays, united by narrower channels. The bay inlet was formerly a river system. Tectonic and karstification processes led to the disintegration of this river. After heavy rains, the waterfall of Sopot spring at Risan appears, and Škurda, another well-known spring, runs through a canyon from Lovćen.

The outermost part of the bay is the Bay of Tivat. On the seaward side is the Bay of Herceg Novi, at the main entrance to the Bay of Kotor. The inner bays are the Bay of Risan to the northwest and the Bay of Kotor to the southeast.

The Verige Strait represents the bay's narrowest section and is located between Cape St. Nedjelja and Cape Opatovo; it separates the inner bay east of the strait from the Bay of Tivat.

Climate

[edit]

The bay lies within the Mediterranean and northwards the humid subtropical climate zone, but its peculiar topography and high mountains make it one of the wettest places in Europe, with Europe's wettest inhabited areas (although certain Icelandic glaciers are wetter[3]). The littoral Dinaric Alps and the Accursed Mountains receive the most precipitation, leading to small glaciers surviving well above the 0 °C (32 °F) mean annual isotherm. November thunderstorms sometimes drop large amounts of water. By contrast, in August the area is frequently completely dry, leading to forest fires. With a maximum discharge of 200 m3/s (7,100 cu ft/s), one of the biggest karst springs, the Sopot spring, reflects this seasonal variation. Most of the time it is inactive but after heavy rain a waterfall appears 20 metres (66 ft) above the Bay of Kotor.

| Station | Height [m] | Type | Character | Precipitation [mm] | Snow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veliki kabao | 1894 | D | perhumid Mediterranean snowclimate | c. 6250 | ap. 140 days |

| Crkvice | 940 | Cfsb | (fs= without summerdryness), perhumid Mediterranean mountain climate | 4926 | 70 days |

| Risan | 0 | Cs’’a | (s’’= double winter rain season), perhumid Mediterranean coast climate | 3500 | 0.4 days |

* classification scheme after Köppen

Two wind systems have ecological significance: Bora and Jugo. Strong cold downslope winds of the Bora type appear in winter and are most severe in the Bay of Risan. Gusts reach 250 km/h (160 mph) and can lead to a significant temperature decline over several hours with freezing events. Bora weather situations are frequent and sailors study the mountains as cap clouds indicate an imminent Bora event. Jugo is a warm humid wind and brings heavy rain. It appears throughout the year but is usually concentrated in autumn and spring.

Monthly and yearly precipitation ranges:

| Station | Period | Height [m] | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | I-XII [mm/m²a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herceg Novi | 1961–1984 | 40 | 230 | 221 | 183 | 135 | 130 | 73 | 28 | 45 | 160 | 181 | 326 | 262 | 1974 |

| Risan | 1961–1984 | 40 | 405 | 342 | 340 | 235 | 153 | 101 | 66 | 123 | 188 | 295 | 423 | 434 | 3105 |

| Grahovo | 1961–1984 | 710 | 351 | 324 | 305 | 251 | 142 | 94 | 55 | 103 | 202 | 416 | 508 | 473 | 3224 |

| Podvrsnik | 1961–1984 | 630 | 407 | 398 | 367 | 305 | 151 | 101 | 77 | 132 | 238 | 465 | 593 | 586 | 3820 |

| Vrbanj | 1961–1984 | 1010 | 472 | 390 | 388 | 321 | 181 | 104 | 70 | 122 | 224 | 369 | 565 | 536 | 3742 |

| Knežlaz | 1961–1984 | 620 | 547 | 472 | 473 | 373 | 207 | 120 | 72 | 136 | 268 | 400 | 629 | 661 | 4358 |

| Crkvice | 1961–1984 | 940 | 610 | 499 | 503 | 398 | 198 | 135 | 82 | 155 | 295 | 502 | 714 | 683 | 4774 |

| Ivanova Korita | 1960–1984 | 1350 | 434 | 460 | 742 | 472 | 128 | 198 | 74 | 46 | 94 | 300 | 694 | 972 | 4614 |

| Goli vrh | 1893–1913 | 1311 | 271 | 286 | 307 | 226 | 188 | 148 | 75 | 70 | 215 | 473 | 415 | 327 | 3129 |

| Jankov vrh | 1890–1909 | 1017 | 424 | 386 | 389 | 346 | 212 | 124 | 55 | 58 | 202 | 484 | 579 | 501 | 3750 |

Hydrology

[edit]- Hydrologic system: karst hydrology ca. 4000 km2, Sopot, Škurda, submerged sources[clarification needed]

- Water area: 87 km2

- Max depth: 60 m

- Average depth: 27.3 m

- Water content:24,12306 km3 (ca. 2.4 mrd m3)

- Highest point: Orjen (1894 m)

- Lowest point: sea surface (0 m)

- Length: 28,13 km

- Widest point: 7 km

- Narrowest point: || 0.3 km

History

[edit]Middle Ages

[edit]

The Sklavenoi, South Slavs, settled in the Balkans in the 6th century.[4][5] The Serbs, mentioned in the Royal Frankish Annals of the mid-9th century, controlled a great part of Dalmatia ("Sorabos, quae natio magnam Dalmatiae partem obtinere dicitur").[6][7] Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos in De Administrando Imperio mentions that, from Croats who came to Dalmatia, one part was separated and took rule in Illyricum.[8] The Slavic, Serbian tribes, consolidated under the Vlastimirović dynasty (610–960).[citation needed] The two principalities of Doclea and Travunia were roughly adjacent at Boka. As elsewhere in the Balkans, Slavs mixed with the Roman population of these Byzantine coastal cities. The Theme of Dalmatia was established in the 870s. According to De Administrando Imperio (ca. 960), Risan was part of Travunia, a Serbian principality ruled by the Belojević family.[citation needed]

After the Great Schism of 1054, the coastal region was under both Churches. In 1171, Stefan Nemanja sided with the Republic of Venice in a dispute with the Byzantine Empire. The Venetians incited the Slavs of the eastern Adriatic littoral to rebel against Byzantine rule and Nemanja joined them, launching an offensive towards Kotor. The Bay was thenceforth under the rule of the Nemanjić dynasty. In 1195, Nemanja and his son Vukan constructed the Church of Saint Luka in Kotor. In 1219, Saint Sava founded the seat of the Eparchy of Zeta on Prevlaka,[9] one of the eparchies of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Due to its protected location, Kotor became a major city for the salt trade. The area flourished during the 14th century under the rule of Emperor of the Serbs Dušan the Mighty who, notorious for his aggressive law enforcement, made the Bay of Kotor a particularly safe place for doing business.[10]

The city of Kotor was under Nemanjić rule until 1371. It was followed by a period of frequent political changes in the region. Local lords from the Vojinović and Balšić noble families fought over the influence in the region. Since 1377, northern parts of the Bay region came under the rule of Tvrtko I Kotromanić, who proclaimed himself King of the Serbs and Bosnia. For several years (1385–1391), the city of Kotor also recognized the suzerainty of the Kingdom of Bosnia. After 1391, it gained political independence, and functioned as a city-state until 1420. Its merchant fleet and importance gradually increased, but so was the interest of the powerful Republic of Venice for the city and the bay region. From 1405 to 1412, the First Scutari War was fought in the region.

Venetian rule (1420–1797)

[edit]In 1420, the city of Kotor recognized the Venetian rule,[11] marking the beginning of an era that would last until 1797. Northern parts of the Bay region still remained under the Kingdom of Bosnia, while southern parts were controlled the Lordship of Zeta, followed by the Serbian Despotate. In the meanwhile, the Second Scutari War was fought in the region, resulting in the peace treaties of 1423 and 1426.[citation needed]

By the middle of the 15th century, northern parts of the Bay region became incorporated into the Duchy of Saint Sava. In 1482, Ottomans took the city of Novi, establishing their rule in the northern parts of the Bay area. Under Ottoman rule, those regions were attached to the Sanjak of Herzegovina. The Ottoman possessions in the Bay region were retaken at the end of the 17th century and the whole area became part of the Venetian Republic, within the province of Venetian Albania. Until the 20th century, the difference between the two parts was visible because the former Ottoman part had an Orthodox majority, while the part that was under Venetian rule had a Catholic majority.[12]

The town of Perast had difficult moments in 1654 when the Ottomans attacked, retaliating against Bokeljs who had sunk an Ottoman ship. The Bokeljs' successful defence of Perast and the Bay received attention all over Europe. It attracted Petar Zrinski, a statesman in Europe who had fought dramatic battles with the Turks. During his three-day sojourn in Perast he presented his legendary sword to the town in recognition for their efforts to defend their homeland, and to stop the Ottoman Empire.[citation needed]

In 1669, according to Andrija Zmajević, hajduks of the Bay[13] wished to build a church, but were denied due to Zmajević's intervention on the providur of Kotor and the captain of Perast.[14] Ottoman travel writer Evliya Çelebi visited the Bay of Kotor and mentioned Croats who lived in Herceg Novi.[15]

Modern history

[edit]

By the Treaty of Campo Formio (1797), the Bay region came under the Habsburg rule. By the Treaty of Pressburg (1805), the region was set to be transferred to the French rule, but that was effectively achieved only after the Treaties of Tilsit (1807). Under the French rule, the Bay region was included in the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy and later in the Illyrian Provinces,[16] which were a part of the French Empire. The region was later conquered by Montenegro with Russian help by Prince-Bishop Petar I Petrović-Njegoš and, in 1813, a union of the bay area with Montenegro was declared. In 1815, the bay was annexed by the Austrian Empire and was included in the province of Dalmatia (part of Cisleithania since 1867). In 1848, when the numerous revolutions sparked in the Austrian Empire, an Assembly of the Bay of Kotor was held sponsored by Petar II Petrović-Njegoš of Montenegro, to decide on the proposition of the Bay's unification with Ban of Croatia Josip Jelačić in an attempt to unite Dalmatia, Croatia and Slavonia under the Habsburg crown.[citation needed]

The Kingdom of Montenegro attempted to take the Bay during World War I. It was bombed from Lovćen, but, by 1916, Austria-Hungary had defeated Montenegro. During Austro-Hungarian rule, the majority of people participated in the Great Retreat with the Royal Serbian Army through Albania. On 7 November 1918, the Serbian army entered the Bay. Within a month, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was formed and was renamed as Yugoslavia in 1929. The Bay was a municipality of Dalmatia until it was re-organized into smaller districts (oblasts) in 1922. It was incorporated into the Oblast of Cetinje and, from 1939, into the Zeta Banovina.[citation needed] Both Ottoman and Austro Hungarian Hercegovina had a narrow exit to the sea, the so-called Sutorina stripe. In 1945 Montenegro was assigned the stripe.[17] According to the 1910 census, the bay had 40,582 inhabitants, of whom 24,794 were Eastern Orthodox and 14,523 Catholic.

The Bay region was occupied by the Royal Italian Army in April 1941, and was included in the Governorate of Dalmatia until September 1943. Since 1945, it was part of the People's Republic of Montenegro.[citation needed]

Culture

[edit]

Most of the region's inhabitants are Orthodox Christians, declaring themselves on census forms of either Montenegrins or Serbians, while a minority are Croatians. The Bay region is under the protection of UNESCO due to its rich cultural heritage.[citation needed]

The Boka region has a long maritime tradition and harbored a strong fleet since the Middle Ages, which historically formed the backbone of the Bay's economy. Kotor was home to a notable naval academy, the Scuola Nautica.[18] The fleet peaked at 300 ships in the 18th century, when Boka was a rival to Dubrovnik and Venice. During the Austro-Hungarian period, the Bay of Kotor produced the majority of sea captains of the Österreichischer Lloyd shipping company.[19]

Historically, inhabitants of both dominant faiths of the Boka region were referred to as Bocchesi (an Italian-language exonym). In 1806, about two-thirds of Bocchesi were adherents of Eastern Orthodoxy, the remaining third being Catholic. Catholicism was the dominant faith in Perast. During the 19th century, Orthodox Bocchesi were strongly in favor of a union with the Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro, while many Catholic inhabitants favored continued Austro-Hungarian rule.[20]

On the landward side, long walls run from the fortified old town of Kotor to the castle of Saint John, far above; the heights of the Krivošije, a group of barren plateaus in Mount Orjen, were crowned by small forts.

The shores of the bay Herceg Novi house the Orthodox convent of St. Sava near (Savina monastery) standing amid surrounding gardens. It was founded in the 16th century and contains many specimens of 17th century silversmiths' work. 12.87 km east of Herceg Novi, there is a Benedictine monastery on a small island opposite Perast (Perasto). Perast itself was for a time an independent state in the 14th century.[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]

The Bokelj (Бокељ) people (pl. Бокељи, Bokelji) are the inhabitants of the Boka kotorska (hence the name) and adjacent regions (near the towns of Kotor, Tivat, Herceg Novi, Risan, Perast).[21] They are an ethnic South Slavic community, many of whom nationally identify as Montenegrin, Serb or Croat. Most are Eastern Orthodox, while some are Roman Catholics.

According to the 2011 Montenegro census, the total population of Boka was 67,456. When it comes to ethnic composition, in 2011 there were 26,435 (39.2%) Serbs, 26,108 (38.7%) Montenegrins, and 4,519 (6.7%) Croats. [22]

|

|

|

|

Notable people

[edit]- Matija Zmajević – shipbuilder

- Andrija Paltašić – typographer

- Nikola Modruški – bishop

- Krsto Čorko[23] – naval captain

- Petar Želalić[24] – naval captain

- Ivan Visin – sailor

- Stjepan Mitrov Ljubiša – politician

- Rambo Amadeus – singer

- Leopold Mandić (1866–1942)

- Osanna of Cattaro (1493–1565)

- Giovanni Bona de Boliris

Gallery

[edit]-

Cathedral of Saint Tryphon in Kotor.

-

Saint-George and Our-Lady-of-the-Reef, two islands off Perast.

-

Town of Perast, Kotor Municipality

-

Bay of Kotor and Illyrian fortresses on the hills 1)Risan 2)Gosici 3)Kremalj (Mirac)

-

Kotor bay from St John Castle.

-

Stone lion and the Bay of Kotor. Perast, Montenegro.

-

The ancient fortifications of Kotor

-

Panorama of the Bay of Kotor

-

Kotor Bay, as seen from the Lovćen mountain.

-

Kotor around 1840

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Welcome to Bay of Kotor". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ D Magaš. "Natural-Geographic Characteristics of the Boka Kotosdka Area As the Basis of Development". Geoadria Vol. 7 No. 1, Croatian Geographical Society and University of Zadar Department of Geography, Zadar, 2002, pp. 53.

- ^ "Late Holocene Glacial History of Sólheimajökull, Southern Iceland" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2014.

- ^ Hupchick, Dennis P. The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 1-4039-6417-3

- ^ Rastko.org, Arheologija 13047 Archived 2013-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Serbian studies, Volumes 2–3, p. 29

- ^ De originibus Slavicis, Volume 1 By Johann Christoph von Jordan, p. 155 Archived 2024-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lujo Margetić, Konstantin Porfirogenet i vrijeme dolaska Hrvata, Vol. 8, 1977. https://hrcak.srce.hr/83642 Archived 2019-11-17 at the Wayback Machine #page=8

- ^ Popović 2002, p. 173.

- ^ Rick Steves Snapshot Dubrovnik Archived 2024-08-14 at the Wayback Machine by Rick Steves and Cameron Hewitt

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 185.

- ^ Miloš Milošević (1988). Hajduci u Boki Kotorskoj 1648–1718. CANU. ISBN 9788672150148.

- ^ Marko Jačov (1992). Le Missioni cattoliche nei Balcani durante la Guerra di Candia (1645–1669). Biblioteca apostolica vaticana. pp. 709–. ISBN 978-88-210-0638-8.

- ^ "MONTENEGRINA - digitalna biblioteka crnogorske kulture i nasljedja". Archived from the original on 2021-10-17. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 187.

- ^ Territorial proposals for the settlement of war in Bosnia Hercegovina - boundary and territorial briefing volume 1 number 3 page 12 by Mladen Klemencic

- ^ Manuale del regno di Dalmazia [Handbook of the Kingdom of Dalmatia]. Battaro. 1872. p. 260.

- ^ Handbook to the Mediterranean, Part 1. London: John Murray. 1881. p. 303.

- ^ Bensman, Stephen (1962). The Russian Occupation of the Region of Kotor Bay, 1806-1807. University of Wisconsin-Madison. p. 7.

- ^ "[Projekat Rastko – Boka] Simo Matavulj – Boka i Bokelji". rastko.org.rs. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "Census 2011 data - Municipalities". monstat.org. Statistical Office of Montenegro. Archived from the original on 2020-07-05. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- ^ "Slavni "Kapetani Boke kotorske"". Radio DUX. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ Petar Želalić famous naval captain, from Boka Kotorska Archived 22 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

Literature

[edit]- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472081497.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Popović, Svetlana (2002). "The Serbian Episcopal sees in the thirteenth century (Српска епископска седишта у XIII веку)". Старинар (51: 2001): 171–184.

- Boka kotorska: Etnički sastav u razdoblju austrijske uprave (1814.-1918. g.), Ivan Crkvenčić, Antun Schaller, Hrvatski geografski glasnik 68/1, 51–72 (2006)