The Blind Watchmaker

First edition cover | |

| Author | Richard Dawkins |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Evolutionary biology |

| Publisher | Norton & Company, Inc |

Publication date | 1986 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | 0-393-31570-3 |

| OCLC | 35648431 |

| 576.8/2 21 | |

| LC Class | QH366.2 .D37 1996 |

| Preceded by | The Extended Phenotype |

| Followed by | River Out of Eden |

The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe without Design is a 1986 book by Richard Dawkins, in which the author presents an explanation of, and argument for, the theory of evolution by means of natural selection. He also presents arguments to refute certain criticisms made on his first book, The Selfish Gene. (Both books espouse the gene-centric view of evolution.) An unabridged audiobook edition was released in 2011, narrated by Richard Dawkins and Lalla Ward.

Synopsis

[edit]

The title of the book refers to the watchmaker analogy made famous by William Paley in his 1802 book Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity.[1] Paley, writing long before Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, held that the complexity of living organisms was evidence of the existence of a divine creator by drawing a parallel with the way in which the existence of a watch compels belief in an intelligent watchmaker. Dawkins, in contrasting the differences between human design and its potential for planning with the workings of natural selection, therefore dubbed evolutionary processes as analogous to a blind watchmaker.

To dispel the idea that complexity cannot arise without the intervention of a "creator", Dawkins uses the example of the eye. Beginning with a simple organism, capable only of distinguishing between light and dark, in only the crudest fashion, he takes the reader through a series of minor modifications, which build in sophistication until we arrive at the elegant and complex mammalian eye. In making this journey, he points to several creatures whose various seeing apparatus are, whilst still useful, living examples of intermediate levels of complexity.

In developing his argument that natural selection can explain the complex adaptations of organisms, Dawkins' first concern is to illustrate the difference between the potential for the development of complexity as a result of pure randomness, as opposed to that of randomness coupled with cumulative selection. He demonstrates this by the example of the weasel program. Dawkins then describes his experiences with a more sophisticated computer simulation of artificial selection implemented in a program also called The Blind Watchmaker, which was sold separately as a teaching aid.

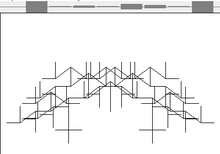

The program displayed a two-dimensional shape (a "biomorph") made up of straight black lines, the length, position, and angle of which were defined by a simple set of rules and instructions (analogous to a genome). Adding new lines (or removing them) based on these rules offered a discrete set of possible new shapes (mutations), which were displayed on screen so that the user could choose between them. The chosen mutation would then be the basis for another generation of biomorph mutants to be chosen from, and so on. Thus, the user, by selection, could steer the evolution of biomorphs. This process often produced images which were reminiscent of real organisms for instance beetles, bats, or trees. Dawkins speculated that the unnatural selection role played by the user in this program could be replaced by a more natural agent if, for example, colourful biomorphs could be selected by butterflies or other insects, via a touch-sensitive display set up in a garden.

In an appendix to the 1996 edition of the book, Dawkins explains how his experiences with computer models led him to a greater appreciation of the role of embryological constraints on natural selection. In particular, he recognised that certain patterns of embryological development could lead to the success of a related group of species in filling varied ecological niches, though he emphasised that this should not be confused with group selection. He dubbed this insight the evolution of evolvability.

After arguing that evolution is capable of explaining the origin of complexity, near the end of the book Dawkins uses this to argue against the existence of God: "a deity capable of engineering all the organized complexity in the world, either instantaneously or by guiding evolution ... must already have been vastly complex in the first place ..." He calls this "postulating organized complexity without offering an explanation".

In the preface, Dawkins states that he wrote the book "to persuade the reader, not just that the Darwinian world-view happens to be true, but that it is the only known theory that could, in principle, solve the mystery of our existence".

Reception

[edit]Tim Radford, writing in The Guardian, noted that despite Dawkins's "combative secular humanism", he had written "a patient, often beautiful book... that begins in a generous mood and sustains its generosity to the end." 30 years on, people still read the book, Radford argues, because it is "one of the best books ever to address, patiently and persuasively, the question that has baffled bishops and disconcerted dissenters alike: how did nature achieve its astonishing complexity and variety?"[1]

Philosopher and historian of biology Michael T. Ghiselin, writing in The New York Times, comments that Dawkins "succeeds admirably in showing how natural selection allows biologists to dispense with such notions as purpose and design". He notes that analogies with computer programs have their limitations, but are still useful. Ghiselin observes that Dawkins is "not content with rebutting creationists" but goes on to press home his arguments against alternative theories to neo-Darwinism. He thinks the book fills the need to know more about evolution that creationists "would conceal from them." He concludes that "Readers who are not outraged will be delighted."[2]

The American philosopher of religion Dallas Willard, reflecting on the book, denies the connection of evolution to the validity of arguments from design to God: whereas, he asserts, Dawkins seems to consider the arguments to rest entirely on that basis. Willard argues that Chapter 6, "Origins and Miracles", attempts the "hard task" of making not just a blind watchmaker but "a blind watchmaker watchmaker", which he comments would have made an "honest" title for the book. He notes that Dawkins demolishes several "weak" arguments, such as the argument from personal incredulity. He denies that Dawkins's computer "exercises" and arguments from gradual change show that complex forms of life could have evolved. Willard concludes by arguing that in writing this book, Dawkins is not functioning as a scientist "in the line of Darwin", but as "just a naturalist metaphysician".[3]

Influence

[edit]The engineer Theo Jansen read the book in 1986 and became fascinated by evolution and natural selection. Since 1990 he has been building kinetic sculptures, the Strandbeest, capable of walking when impelled by the wind.[4]

The journalist Dick Pountain described Sean B. Carroll's 2005 account of evolutionary developmental biology, Endless Forms Most Beautiful, as the most important popular science book since The Blind Watchmaker, "and in effect a sequel [to it]."[5]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Radford, Tim (30 April 2010). "Richard Dawkins' watchmaker still has the power to open our eyes". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Ghiselin, Michael T. (14 December 1986). "We are all Contraptions". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Willard, Dallas. "Reflections on Dawkins' The Blind Watchmaker". Dallas Willard. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ (in Spanish)Theo Jansen. Asombrosas criaturas Archived 5 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine. An exhibition of Theo Jansen's work in Espacio Fundación Telefónica, Madrid, Spain.

- ^ Pountain, Dick (November 2016). "Nature's 3D printer exposes Pokémon Go as a hollow replica". PC Pro (265): 26.

References

[edit]- Dawkins, Richard (1996) [1986]. The Blind Watchmaker. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-31570-3.

- Maynard Smith, John (1986). "Evolution for those that have ears." New Scientist 112 (20 Nov.): 61.

External links

[edit]- We Are All Contraptions – review by Michael Ghiselin