Clydebank, Millers Point

| Clydebank | |

|---|---|

Clydebank, pictured in 2019. | |

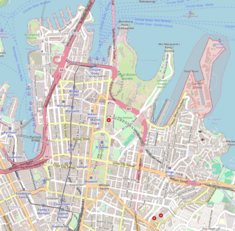

| Location | 43 Lower Fort Street, Millers Point, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°51′23″S 151°12′25″E / 33.8565°S 151.2070°E |

| Built | 1824–1825 |

| Architectural style(s) | Old Colonial Regency |

| Official name | Clydebank; Bligh House; Holbeck; St Elmo |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 524 |

| Type | House |

| Category | Residential buildings (private) |

| Builders | Robert Crawford |

Clydebank is a heritage-listed residence at 43 Lower Fort Street, in the inner city Sydney suburb of Millers Point in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was built from 1824 to 1825 by Robert Crawford. It is also known as Bligh House, Holbeck and St Elmo. It has also served as an art gallery and as offices in the past. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

History

[edit]In June 1823 Robert Crawford, Principal Clerk to the NSW Colonial Secretary, was granted land at Cockle Bay, part of which survives as the present property dating from 1824. Arriving in Sydney in 1821 from Scotland, Crawford soon managed to build up extensive holdings including farms called Doonside, Hill End and Ellalong. In a letter of February 1825 he wrote to his father "I am just finishing a house near Dawes Battery. I got a town allotment and as I am not allowed lodging money. I thought it advisable to build – I call it Clyde Bank, it looks into Cockle Bay and is ten minutes walk from the office."[1]

By 1828 Crawford was in financial difficulties and was forced to sell Clyde Bank to John Terry Hughes of the Albion Mills. Hughes sold the property to Samuel Lyons in 1835, and within the year it was again sold to Isaac Simmons and then shortly after to Captain Joseph Moore, Master Mariner. With his son Henry, Moore bought the Long and Wright Wharf below in Cockle Bay. Moore's Wharf became one of the two best such shipping establishments in Sydney - the other being Campbell's Wharf in Sydney Cove. It was from Moore's Wharf that in 1851 the first shipment of gold was loaded for Britain.[1]

At this time parcels of land had been amalgamated with the house land. As with so many others in the 1840s Captain Moore became bankrupt in 1844 and was forced by the Trustees of his properties to sell the property to Robert Campbell junior in 1845.[1] Captain Moore's sale notice in The Sydney Morning Herald in 1844 gave details of the house:[1]

"Ground floor – Entrance Hall, two drawing rooms, dining room, library and pantry. The drawing and dining rooms have handsome marble chimney pieces." Originally there would have not been a stair from the ground floor to the basement for security, noise and kitchen smells. A stair went up from the kitchen back door to the western verandah, where a narrow pantry may have been located for the trays to rest on their way to the dining room.

"First Floor: Four bedrooms and two dressing rooms." The two dressing rooms are now two bathrooms and a small kitchen. The fireplaces were all made of Marulan stone, some badly damaged and have been repaired in the same stone.

"The basement contains kitchen, laundry, cellar and two servant's rooms. In the rear is a yard with a three stall stable. Coach house, hay loft and a well of water and pump."

Robert Campbell owned the house until his death in 1859 but his family continued to own it until it was sold to Morris Nelson in 1874. Nelson died not long after, and the property was transferred to his widow Caroline in 1880.[1] It was resumed from the Nelson family by the Government of New South Wales in 1903 for the Sydney Harbour Trust. The property was tenanted by many people involved in maritime occupations including stevedoring and tug ownership.[2][1]

In 1958 architect John Fisher (member of the Institute of Architects, the Cumberland County Council Historic Buildings Committee and on the first Council of the National Trust of Australia (NSW) after its reformation in 1960), with the help of artist Cedric Flower, convinced Taubmans to paint the central bungalow at 50 Argyle Place. This drew attention to the importance of The Rocks for the first time. As a result, Fisher was able to negotiate leases for Bligh House (later Clydebank) and houses in Windmill Street for various medical societies.[3][1]

From 1961 until 1990 it was leased by the Australian College of General Practitioners after which date the leasehold was purchased by an individual for use as a private gallery of early colonial art and furniture. The house has at various times been called Holbeck, St Elmo and, from 1940, Bligh House.[1][2][3]

The buildings on the land were constructed at different times. They are: Main building – 1824; Coach House – c. 1845; Kitchen – c. 1865, demolished 1919; "Link" structure – 1972; Rear wing – 1919, demolished in 1993. In 1962 some work was carried out by the architect Morton Herman and a new kitchen built in a link structure, joining the coach house (now the garage) with the house.[3][1][2]

Description

[edit]

The buildings on the land were constructed at different times. They are:

- Main building: 1824;

- Coach House: c. 1845

- Kitchen: c. 1865, demolished 1919;

- Link structure: 1972;

- Rear wing: 1919, demolished in 1993.

In 1962 some work was carried out by the architect Morton Herman and a new kitchen built in a link structure, joining the coach house (now the garage) with the house.[3][1][2]

House

[edit]Clydebank is a good example all of the main features of Old Colonial Regency style. The building has two upper storeys from Lower Fort Street, with a basement that is cut into the steep slope down to Downshire Street. The upper floors are rendered and lined over brickwork, whilst the basement is in the rough coursed stone expected from an 1820s building. There is a finish on the ground floor that has a very high gloss level, perhaps an attempt to deter graffiti.[1]

The building is divided into the typical Georgian five bays of twelve pane windows to the upper floor with timber French doors with transom light sashes below, each detailed with offset glazing beads typical of Regency detailing. The central entry door is a Georgian flush beaded six panel door with sidelights and a rectangular transom light sash with ornate glazing beads. The central upper window is a feature not often seen in a Georgian building, it is divided into two narrower openings either side of a stone pier each with an eight pane double hung window, which gives the impression the building was used as two residences, despite only having a single entry door. This window may have been introduced as a more recent alteration. The building had shutters until quite recently, but these have now been removed.[1]

The building is set back from the street behind rendered classical posts and an iron palisade fence, and the ground has been cut away to open up to a basement verandah underneath the timber framed ground floor entry balcony. The basement is in rough coursed stonework, including stone flagging and has a stone wall underneath the main villa wall. The main balcony is supported on stone walls and iron posts, and features cedar Doric columns on the ground floor level. The columns are paired at the corners and on both sides of the entry and support a hipped slate verandah roof. The hipped roof to the villa is also finished in slate with narrow timbered eaves, and is a U-shaped roof with a concealed central valley that runs parallel to the street and empties into what must be an internal downpipe against the neighbour's wall. There are four chimneys arranged symmetrically on the perimeter.[1]

A link building in Georgian style is attached to the side of the main villa and connects to the face stone garage building. The link building is a 1962 addition in keeping with the style, and whilst it appears the garage is an early structure (Coach House) it has the appearance of having been modified relatively recently. It has a large central vehicle opening with face stone walls either side, a beaded board gable face under a simple barge with gutter returns that imply a pediment. The stone side walls to the driveway appear to be recent construction. It appears the original stable has been demolished.[1]

The rear face of the building has a correct Georgian upper level with five original 12 pane windows. The ground floor has what appears to be a rebuilt verandah, which has been infilled with glazed doors and highlight windows. This verandah sits on exposed brick piers, which are rendered with a classical capping, and is supported by a large beam. The basement is deeply recessed behind this face.[1]

The interior of the building is reportedly highly intact in the 1992 Conservation Management Plan. From the original description the building appears based on a simple Georgian four room plan with two rooms either side of a central entrance hallway. On the ground floor the two front rooms were drawing rooms; with a dining room and library / pantry behind, including a curved wall that incorporates a Georgian curved door. The main rooms have marble and Marulan sandstone chimneys with Regency iron fire grates, which are reportedly intact along with their original joinery features. The central entrance hall features an original cedar staircase to the upper level, but the basement servant quarters were connected externally via the rear verandah (which has now been enclosed). The first floor features four bedrooms (two front and back) with what were originally two dressing rooms. Whether this accounts for the odd front central window is not known. These service spaces have since become bathrooms and a kitchen. The basement consisted of a kitchen, laundry, cellar and two servant's rooms. The layout of the original house is a dramatic demonstration of how social roles have changed.[2][1]

Heritage listing

[edit]Clydebank was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Clydebank". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00524. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ a b c d e LEP, 2005

- ^ a b c d Lucas & McGinness, 2012

Bibliography

[edit]- "Colony Walking Tour". 2007.[permanent dead link]

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Colony Walking Tour" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- David Sheedy Pty Ltd (1992). A conservation plan for commercial premises at 43 Lower Fort Street Dawes Point, Sydney, N.S.W.

- Lucas, Clive & McGinness, Mark (2012). 'John Fisher, 1924-2012 - Champion of the state's structures'.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Paul Davies P/L (1996). Millers Point and Walsh Bay Heritage Review.

Attribution

[edit]![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Clydebank, entry number 524 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Clydebank, entry number 524 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links

[edit]- Paul Davies Pty Ltd (March 2007). "Millers Point and Walsh Bay Heritage Review" (PDF). City of Sydney.

- "Lower Fort Street". Millers Point Community. n.d. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.