Blackamoor (decorative arts)

Blackamoor is a type of figure and visual trope in European decorative art, typically found in works from the Early Modern period, depicting a man of sub-Saharan African descent, usually in clothing that suggests high status. Common examples of items and objects decorated in the blackamoor style include sculpture, jewellery, and furniture. Typically the sculpted figures carried something, such as candles or a tray. They were thus an exotic and lightweight variant for the "atlas" in architecture and decorative arts, especially popular in the Rococo period.

The term "blackamoor" or "black moor" was once a general term for black people in English,[1] "formerly without depreciatory force" as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it.[2] The style is now viewed by some as racist and culturally insensitive.[3] However, blackamoor pieces are still produced, mainly in Venice, Italy.

Jewelry and decorative arts

[edit]

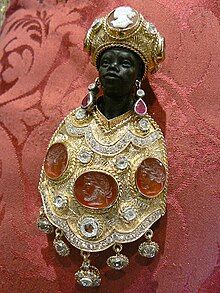

In jewelry, blackamoor figures usually appear in antique Venetian earrings, bracelets, cuff links, and brooches (Moretto Veneziano). Blackamoor jewelry is also traditionally produced, based on legend found in Fiume, such as earrings and brooches under the name Morčić or Moretto Fiumano.[4][5][6]

Some contemporary craftspeople continue to make individual pieces; however, production of blackamoor jewelry is becoming more rare, due to the decorative style increasingly being viewed as problematic and offensive for its depiction of dark-skinned people as "exotic" and decorative.

Blackamoor figures are typically male, sometimes depicted with a head covering such as a turban. Sculptures are typically carved from ebony, or painted black to contrast with the bright colors of the embellishments. Depictions may only represent the head, or head and shoulders, facing the viewer in a symmetrical pose.

In decorative sculpture, the full body is depicted, either to hold trays as a servant figure, or bronze sconces to hold candles or light fixtures. They may be incorporated into small stands, tables, or andirons, and are often portrayed in pairs. Often, blackamoor figures are depicted in acrobatic positions that would be physically impossible to hold for any extended length of time. Notable sculptors of blackamoor figures include Andrea Brustolon (1662–1732), who is considered by some[who?] to be the most important artist of blackamoor sculptures.

Collections

[edit]The Mohr mit Smaragdstufe ("Moor with Emerald Cluster"), in the collection of the Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden, Germany, created by Balthasar Permoser in 1724, is a richly decorated statue with jewels, 63.8 cm (25.1 in) tall.

The Dunham Massey Hall sundial depicts a blackamoor carrying the sundial above his head. From the period of the Atlantic slave trade, it has also been categorised as a 'kneeling slave'. The statue was set up as one monument to honour the 1st Earl of Warrington by his son, the second Earl in c. 1735. It was cast after a model by John Nost I for William III of England's Privy Garden at Hampton Court Palace.[7] In June 2020, the National Trust removed the Grade II-listed statue from the forecourt of Dunham Massey Hall.[8][9]

Aleksandr Pushkin had a blackamoor figurine on his desk to remind him of Abram Petrovich Gannibal, his great-grandfather. This figure can be seen in his former St. Petersburg apartment, now turned into a museum.[citation needed]

Vogue editor Diana Vreeland had a famous collection of blackamoor figurines[10][11] and blackamoor jewelry and famously said: “Have I ever showed you my little blackamoor heads from Cartier with their enameled turbans? I’m told it’s not in good taste to wear blackamoors anymore, but I think I’ll revive them.”[12] Civil-Rights Activist and pop star Anita Pointer of the Pointer Sisters has some blackamoor pieces in her extensive collection of black memorabilia that she started in the 1970s. As a child, she witnessed extreme racial oppression in her mother's hometown, Prescott. When she started traveling abroad, she was amazed that she could find collectible pieces in other parts of the world that told the same story as Black American History.[13][14][15]

Heraldry

[edit]

In heraldry, a blackamoor may be a charge in the blazon, or description of a coat of arms. The isolated head of a moor is blazoned "a Maure" or a "moor's head".

The reasons for the inclusion of a blackamoor head vary. The Moor's head on the crest that appears on the arms of Lord Kirkcudbright, and in consequence the modern crest badge used by Clan MacLellan is supposed to derive from the killing of a moorish bandit known as Black Morrow.[16] The blazon is a naked arm supporting on the point of a sword, a moor's head.[17] Other examples appear to depict captives; the flag of Sardinia and the neighboring Corsica, derived from the coat of arms of Aragon, depict Maures' heads with bandanas.

Sculpture

[edit]

Blackamoor figures were also used in larger sculptures, such as on Blackamoor Bridge in Ulriksdal Palace, Sweden.

Fred Wilson,[18] an African-American sculptor, displayed an installation at the 2003 Venice Biennale that incorporated blackamoors.[19] Wilson placed wooden blackamoors carrying acetylene torches and fire extinguishers. Wilson noted that such figures are so common in Venice, few people notice them. He said, "They are in hotels everywhere in Venice ... which is great, because all of a sudden you see them everywhere. I wanted it to be visible, this whole world which sort of just blew up for me."[19]

Racism

[edit]Blackamoors have a long history in decorative art, stretching back to 17th century Italy and the famous sculptor Andrea Brustolon (1662–1732). They are often recognized for depictions of slaves and the ornamental pieces that they inspired.

In modern times, the blackamoor is considered to have racist connotations, with its association to colonialism and slavery.[3] Art historian Adrienne Childs criticised the "romanticised" depictions and interpretations of blackamoor pieces, arguing that the depictions of black people in the blackamoor style obscured and made palatable the existence of slaves in the colonies, and evidenced "a culture that marginalised and dominated blacks".[20][21][22]

Etymology

[edit]The term is ultimately derived from the name of the Moors, a historic people in the western Mediterranean. Other similarly derived words include Kammermohr, Matamoros, Maure, Mohr im Hemd, Moresca, Moresche, Moresque, Moreška, Morianbron, Morisco, Moros y cristianos, and Morris dance.

See also

[edit]- Black Madonna

- Cigar store Indian

- Lawn jockey

- Concrete Aboriginal

- Representation of slavery in European art

References

[edit]- ^ Das, Nandini; Melo, João Vicente; Smith, Haig Z.; Working, Lauren (2021). "Blackamoor/Moor". Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 40–50. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1t8q92s.7. ISBN 9789463720748. JSTOR j.ctv1t8q92s.7. S2CID 242157432.

- ^ "blackamoor", OED. The form with the connecting "a", whose origin is unclear, was first recorded in 1581, as "black a Moore".

- ^ a b Holt, Bethan (22 December 2017). "Princess Michael of Kent prompts controversy after wearing 'racist' 'blackamoor' brooch to lunch with Meghan Markle". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ ""Morčić" - The Lucky Charm from Rijeka | Croatia.hr". “Morčić” - The Lucky Charm from Rijeka | Croatia.hr.

- ^ Kresta, Edith (June 9, 2019). "Kolumne Aufgeschreckte Couchpotatoes: "Die Welt ist kompliziert geworden"". Die Tageszeitung: Taz – via taz.de.

- ^ "Risk Change residency: Meet Fotini Gouseti".

- ^ "A sundial borne by a life-size, kneeling figure of an African man". www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk. National Trust. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "Dunham Massey says it is "reviewing" a statue depicting a black figure carrying a sundial". Altrincham Today. 2020-06-10. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- ^ Prior, David (11 June 2020), "Dunham Massey removes sundial statue as National Trust admits it causes "upset and distress"", Altrincham Today, retrieved 14 June 2020

- ^ "Is Codognato's blackamoor jewelry at SF exhibit racist?". 22 December 2017.

- ^ Allen, Henry (1980-11-28). "Diana Vreeland's Vision of Allure". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ "Blackamoor". 7 November 2013.

- ^ "Anita Pointer: Civil-Rights Activist, Pop Star, and Serious Collector of Black Memorabilia".

- ^ The Celebrity Collector: Anita Pointer of the Pointer Sisters has a huge collection of black memorabilia, Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia

- ^ [Special Things Black Americana Collection Curated by Anita Pointer] (catalog book). Foreword by Professor Fritz Pointer With R J McKain Melissa Simpson

- ^ "MacLellan". Myclan.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- ^ "Mac Lellan". Celticstudio.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ "Fred Wilson biography". PBS. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b Hoban, Phoebe (28 July 2003). "The Shock of the Familiar, New York Metro, 2003". Nymag.com. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Childs, Adrienne L. (2010). "8". In Cavanaugh, Alden; Yonan, Michael E. (eds.). The Cultural Aesthetics of Eighteenth-Century Porcelain. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0754663867.

- ^ Bazilian, Emma (28 August 2020). "There's No Excuse for Buying or Decorating With Blackamoors". housebeautiful.com. House Beautiful. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Symington, Emily (29 August 2020). "Racist Porcelain: The Trend of the "Blackamoor" in Europe". varsity.co.uk. Varsity. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.