Bhatkal

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

Bhatkal | |

|---|---|

Location in Karnataka, India | |

| Coordinates: 13°58′01″N 74°34′01″E / 13.967°N 74.567°E[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | Karnataka |

| District | Uttara Kannada |

| Government | |

| • Type | Town Municipal Council |

| • Body | Bhatkal Town Municipal Council |

| Area | |

• Total | 355.50 km2 (137.26 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

• Total | 161,576 |

| • Density | 450/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Bhatkally, Bhatkalite |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Kannada |

| • Regional/Spoken | Kannada, Urdu, Nawayathi (Konkani)[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 581320 |

| Telephone code | +91-8385 |

| Vehicle registration | KA-47 |

| Website | bhatkaltown |

Bhatkal is a coastal town in the Uttara Kannada District of the Indian state of Karnataka. Bhatkal lies on National Highway 66, which runs between Mumbai and Kanyakumari, and has Bhatkal railway station which is one of the major railway stations along the Konkan Railway line, which runs between Mumbai and Mangalore.

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]Bhatkal was named after Jain Grammarian, Bhattakalanka, who hailed from Hadwalli village, a town on the state highway toward Jog Falls, Shimoga.[3] It was also known as Susagadi, and Manipur in Sanskrit.[4] The Hamilton referred to it as Batuculla, which means 'Round town'.[5]

Some have claimed that Marathi influence is responsible for the word's derivation. According to Deshabandhu M. Shanker Linge Gowda, when the military leaders of the Patwardhan family under the Peshwas used to periodically invade and pillage the Manipura kingdom, they called it Vatkul, which means "hills around the town," because the Manipura fort was located in a valley surrounded by hills. In slang, Vatkul has now evolved into Bhatkal.[6][7]

The Bhatkal term originated and can be found in one of the oldest manuscripts of Nawayathi from 1100 A.H. (or 1688 A.D.) by Akhun Seedy Mohammed. The author mentions the old name for bhatkal as Abadaqilla (آبادقلعه). But the word itself is susceptible of alteration, and it is quite likely that initially it was 'Abadaqilla,' meaning 'inhabited fort,' and subsequently changed into badaqilla, and finally Bhatkal. Such a name can be applied only by Arabs, who have been associated with the place for a very long time.[8][7]

Name variations include Batigala (by Friar Jordanus, 1328), Batticala (by Barbosa, 1510), Baticala (De Barros), Batticola (Logan, 1887).

Medieval History

[edit]Bhatkal witnessed the rise and fall of several dynasties and rulers. Chola empire under Aditya I, his son, Parantaka I, and Sundara Chola, also known as Parantaka Chola II, initially invaded and conquered territories in Kannada country, between Gangavadi on the Mysuru plateau and Bhatkal on the Sahyadri Coast, between 880 CE and 975 CE. They later built the Solesvara Temple to commemorate their victory over the region.

In 1291, it was a part of the Hoysala Empire before passing into the Nawayath Sultanate's control. Bhatkal was governed by the Nawayath Sultanate (Honnur) from the beginning of the 14th century until 1350s.[9][10] According to Ibn-e-Battuta, it was the vassal state under the rular named "Haryab," which the historian Goarge Moraes has identified as the Harihara-nripala of the unknown Kingdom of Gersoppa.[11][12] Later, when it was under the control of the Vijayanagar Empire, spices, sugar, and other masalas were traded with them.[9][10] According to Ibrahim Khori, powdered sugar, brown sugar, as well as sugar itself, were produced in Bhatkal.[13]

In 1479, Bhatkal and Honnavar got once again attacked by the Vijayanagar Empire over an alleged conspiracy over the trade between the Bahmani Sultanate.[9][14] Vijayakirthi II constructed a town named 'Bhattakala' for his disciple, the king Devaraya. The rulers of Haduvalli were from the Suluva (Jain) Dynasty, and the Bhattakalanka was the last and well-known grammarian of Haduvalli as per the Biligi Ratnatraya Basadi inscription.[15] At the time of Narasimha Deva Raya, he ended the tyranny of Virupaksha and re-established the friendship between the Nawayath.[16]

Modern History

[edit]On 28 August 1502, Vasco de Gama-led Portuguese forces attacked and burned the port in the town that was under the control of the Kingdom of Gersoppa, a vassal state of the Vijayanagara Empire, and forced it to comply with Portuguese demands.[17][18] In 1606, it came under the control of the Nayakas of Ikkeri (also known as the Nayakas of Keladi) after the war between Venkatappa Nayaka and Bairadevi.[14] In 1637, it became the territory of the Dutch East India Company.[19] The British were unsuccessful in their attempts to establish an agency through locals in 1638 and a corporation in 1668.[4]

The Keladi Nayakas invited Kazi Mahmoud, who was a grandson of the Chief Kazi of the Adil Shahi kingdom of Bijapur, to settle in Bhatkal in the year 1670. The revenue of Tenginagundi village was given to Kazi Mahmoud. The Kazi family of Bhatkal is popularly known as the Temunday Family due to the ownership of lands in Tenginagundi. Many Nawayath Muslims were appointed to the administrative positions. The families of these nobles from Nawayath still use their surnames as Ikkeri and are mainly settled in and around Bhatkal. The Golden Kalasa on the dome of Bhatkal Jamia Masjid, popularly known as 'Chinnada Palli' meaning 'Golden Mosque' is believed to be a generous gift from Keladi rulers.

From the Keladi rulers, Bhatkal passed on to the Mysore Sultanate. Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan made Bhatkal the main base on the Canara Coast for their newly built naval force, with the help of the Dutchman Joze Azelar.[20] Later, Tipu Sultan built a mosque in 1793, and a street was named after him. One of Tipu's wives was from Bhatkal.[21] Bhatkal later came into the hands of the British Empire in 1799 after they defeated Tipu. In 1862, Bhatkal was annexed to the Bombay Presidency. With the reorganization of the state in 1956, the town became a part of Karnataka State in 1960, and the sub-taluks of Bhatkal and Supa were upgraded into full-fledged taluks.[22]

Culture

[edit]The residents celebrate festivals such as Eid ul Fitr, Ramadan, Eid al azha, Muharram, Milad un nabi, Makara Sankranti, Nagara Panchami, Krishna Janmashtami, Ganesh Chaturthi, Navaratri, Deepavali. Folk sports like Kambala and folk arts like Yakshagana are also popular. Unlike other states, Nawayathi men wear lungis, which are stitched in the middle and are cylindrical in shape.[23]

Cuisine

[edit]Bhatkali cuisine is a blend of Arabian and Konkan cuisine. Bhatkali biryani is an integral part of the Nawayath cuisine and a specialty of Bhatkal, prepared with basmati rice that has been spiced with full garam masala and saffron. Separately, pieces of mutton, chicken, fish, or prawns are cooked. Some people even refer to it as a layered korma and rice meal with fried onions, curry, or mint leaves on top. Another type of biryani is shayya biryani, made from vermicelli (shayyo) instead of rice.[24][25] The dishes used for breakfast are theek and goad thari (sweet and spicy semolina), gavan or thalla shayyo (wheat or rice vermicelli), varieties of appo (pancakes), fau (poha), theek and goad khubus (sweet and spicy bread), masala poli (heavy spiced paratha), gavan poli (wheat paratha), and puttu (steamed cakes).[26]

Transport

[edit]Bhatkal is connected to other cities and states in India by roads and railways. The National Highway 66 (India) crosses the town, which had a major impact on its development. Under the Konkan Railway, many trains run day and night to and from the town. The Bhatkal railway station has two platforms. The nearest airports to Bhatkal are Mangalore International Airport and Goa-Dabolim International Airport. The town has one large, one medium, and one small fishing port.

Demographics

[edit]As per the 2011 India census, Bhatkal Taluk had a population of approximately 161,576 out of which, 49.98% were males and 50.02% were females. Bhatkal has an average literacy rate of 74.04%, with 78.72% and 69.36% of male and female literacy, respectively. Around 11% of the town's total population is under age 5. Scheduled Castes constitute 8.87% and Scheduled Tribes constitute 5.67% of the total population.[29]

Governance

[edit]

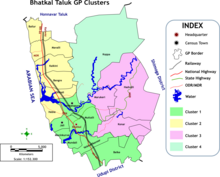

Bhatkal municipality was founded in 1890 and was part of Honnavar Taluk; a decade later, in 1903, the income was 6500 rupees. Two small mosques and two large mosques existed within the town.[4] The town municipal council is divided into 23 wards, for which elections are held every 5 years.[28] Bhatkal Taluka has 15 Gram Panchayats, one Town Panchayat, and one Town Municipal Council, whereas it has 59 villages, 2 census towns, and Bhatkal as its headquarter.[30] Bhatkal is a State Assembly constituency in Uttara Kannada district and the coastal Karnataka region of Karnataka. It is a part of the Uttara Kannada Parliamentary constituency.[31] Mankal Vaidya, of the INC, is the incumbent MLA.[32]

Notable people

[edit]- Ilyas Nadwi Bhatkali, Indian Islamic scholar, founder of Moulana Abul Hasan Ali Nadvi Academy, Bhatkal and its Quran Museum[33]

- Mohammed Abdul Aleem Qasmi, Indian newspaper editor of Naqsh-e-Nawayath, the only newspaper in Nawayathi[2]

- Rajoo Bhatkal (born 1985), Indian cricketer, captain of Malnad Gladiators

- Satyajit Bhatkal, Indian director of film and television

- Shamshuddin Jukaku, Indian politician, first minister from Bhatkal in the Government of Mysore State, deputy chief minister in the 1950s[34]

- SM Syed Khaleel, Indian community leader, founder of institutions such as Jamia Islamia Bhatkal, awarded the Karnataka Rajya Utsav Award[34]

- Zubair Kazi, Indian-American businessman, second-largest KFC franchisee[35][34]

- Pandari Bai (1930–2003), Indian actress in South Indian cinema

- Mynavathi (1935–2012), Indian actress and younger sister of Pandari Bai.

- Maulana Abdul Bari Nadwi (1962–2016), imam and khateeb and principal of Jamia Islamia Bhatkal[36]

- Mohammed Hussain Fitrat (d. 2018), better known as Fitrat Hussain Bhatkali, Indian poet of Nawayathi, Konkani and Urdu[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Falling Rain Genomics, Inc – Bhatkal

- ^ a b "Connecting Konkan with Arabia via Iran: The history of Nawayathi, the language of Bhatkali Muslims". Two Circles. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "A confluence of faiths". Deccan Herald. 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Hunter, William Wilson (1907–1909). The Imperial gazetteer of India. Oxford. p. 90.

- ^ Hamilton, Francis (1807). A journey from Madras through the countries of Mysore, Canara, and Malabar, performed under the orders of the most noble the Marquis Wellesley, governor general of India, for the express purpose of investigating the state of agriculture, arts, and commerce; the religion, manners, and customs; the history natural and civil, and antiquities, in the dominions of the rajah of Mysore, and the countries acquired by the Honourable East India company. London, T. Cadell and W. Davies.

- ^ Gowda, Sankar Linge (1944). Bhatkal harbour scheme: Karnataka Shipbuilding & Transport Co., ltd. s.n.] (Unpublished). OL 5241894M.

- ^ a b D'Souza, Victor S. (1955). The Navayats Of Kanara (1955). pp. 52–53.

- ^ Mohammed, Akhun Seedy (1688). Haza Kitab Ahkam-ul-Islam (in Konkani).

- ^ a b c Barbosa, Durate (1918). The Book Of Durate Barbosa. p. 187/191.

- ^ a b Jordanus, Catalani; Yule, Henry (1863). Mirabilia descripta : the wonders of the East. London : Printed for the Hakluyt Society.

- ^ Moraes, George M. (1939). "Haryab of Ibn Batuta". Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 15: 37–42.

- ^ بطوطة, محمد بن عبد الله ابن; الكلبي, ابن جزي (17 May 2020). رحلة ابن بطوطة تحفة النظار في غرائب الأمصار وعجائب الأسفار (in Arabic). دار القلم للطباعة و النشر و التوزيع - بيروت / لبنان. ISBN 978-9953-72-182-8.

- ^ إبراهيم, خوري، (1999). سلطنة هرمز العربية: سيطرة سلطنة هرمز العربية على الخليج العربي (in Arabic). مركز الدراسات والوثائق،. p. 123.

- ^ a b Shastry, Bhagamandala Seetharama (2000). Goa-Kanara Portuguese Relations, 1498-1763. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-848-6.

- ^ Desai, P. B. (1957). Jainism in South India and some Jaina Epigraphs. p. 125.

- ^ ندوی, ڈاکٹرحامداللہ (1 October 1978). "ماہنامه برہان". ماهنامه برهان (in Urdu). دہلی.

- ^ Logan, William (1887). Malabar Manual, Vol. 1. Superintendent, Government Press (Madras). ISBN 978-81-206-0446-9.

- ^ Danvers, Frederick Charles (1894). The Portuguese In India Vol.1. p. 82.

- ^ O'Brien, Patrick (2002). Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (30 March 2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740-1849. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ^ Ilyas Nadvi, Moulana Mohammad (14 November 2013). Seerat Sultan Tipu Shaheed (in Urdu).

- ^ "DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK UTTARA KANNADA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY" (PDF). Directorate of Census Operations Karnataka.

- ^ Hallare, Yahya (25 December 2014). "Bhatkal: 100-year celebration of Majlis-e-Islah Wa Tanzeem begins with huge procession". Bhatkal: Daijiworld Media Network.

- ^ Aravamudan, Sriram (2 September 2018). "Bhatkal: A food story". Mint.

- ^ Mallik, Prattusa (10 September 2022). "This weekend, explore authentic Bhatkal cuisine in Bengaluru". Indian Express.

- ^ Kola, Aftab Husain (14 January 2014). "Forgotten flavours". Deccan Herald.

- ^ "Karnataka State Minorities Commission | www.karmin.in". www.karmin.in.

- ^ a b "Bhatkal Religion Data 2011". Census 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Census of India – Population Enumeration Data (Final Population)". Census of India 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India, New Delhi-110011.

- ^ "List of villages in bhatkal".

- ^ "Bhatkal Election Result 2018 Live: Bhatkal Assembly Elections Results (Vidhan Sabha Polls Result)". News18. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Bhatkal Assembly Constituency Page". partyanalyst.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014.

- ^ Kumar, Amit (27 June 2017). "The House of Quran in Bhatkal: A photo essay". TwoCircles.net.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Amit (29 June 2017). "Five people who have made Bhatkal proud and you must know of". TwoCircles.net.

- ^ "Initiatives for youth, women: How one couple is helping Bhatkal shed the terror tag". The Indian Express. 17 May 2015.

- ^ Rodrigues, Michael (17 February 2016). "Bhatkal: Legendary scholar, Principal of Jamia Islamia, Moulana Abdul Bari Nadwi passes away". Mangalorean.com.

- ^ "اردو کے عظیم شاعر فطرت بھٹکلی گمنامی کی جی رہے ہیں زندگی". News18 Urdu. 12 August 2016.

External links

[edit]- Bhatkal, Town Municipal Council

Works related to Bhatkal. Otto's encyclopedia at Wikisource

Works related to Bhatkal. Otto's encyclopedia at Wikisource Works related to Bhatkali. Castes and Tribes of Southern India at Wikisource

Works related to Bhatkali. Castes and Tribes of Southern India at Wikisource- This is Bhatkal, where commerce & religion play chicken. 19 May 2018. Newslaundry.

- "A Place Called Bhatkal". Open. 26 March 2015.