SS Belgenland (1914)

Painting of Belgenland in 1931 by Alfred J Jansen

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake | |

| Owner | |

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | |

| Route |

|

| Ordered | March 1912 |

| Builder | Harland & Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number | 391 |

| Launched | 31 December 1914 |

| Completed | 21 June 1917 |

| Maiden voyage |

|

| Refit | 1923 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scrapped 1936 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 670.4 ft (204.3 m) |

| Beam | 78.4 ft (23.9 m) |

| Draught | 36 ft 3 in (11.0 m) |

| Depth | 44.7 ft (13.6 m) |

| Decks | 9 |

| Installed power | 2,653 NHP, 18,500 ihp |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph) |

| Capacity |

|

| Troops | 3,000 |

| Crew |

|

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

SS Belgenland was a transatlantic ocean liner and cruise ship that was launched in Belfast, Ireland in 1914 and scrapped in Scotland in 1936. She was renamed Belgic in 1917, reverted to Belgenland in 1923, and renamed Columbia in 1935.

Throughout her career the ship was owned and operated by the International Mercantile Marine Company or its subsidiaries. IMM ordered Belgenland as a new flagship for its Belgian-based Red Star Line, but the First World War delayed her completion. Germany occupied Belgium in the First World War, so IMM had Belganland completed in 1917 as a cargo ship, transferred to the UK-based White Star Line and renamed Belgic. In 1918 she was converted into a troop ship.

In 1922 the ship was at last fitted out as a passenger liner. In 1923 she was transferred back to Red Star Line and her name was changed back to Belgenland. From 1924 onward she made her name making annual cruises around the World, leaving New York in November or December and returning in April the next year. She pioneered cruise ship visits to destinations including Bangkok and Bali, and steamed almost 250,000 miles without defect.

In 1927 IMM transferred Belgenland's ownership to the UK-based Frederick Leyland & Co, but kept Red Star Line as her managers. In 1935 IMM transferred her ownership to the US-based Atlantic Transport Line, renamed her Columbia, and made Panama Pacific Line her managers.

In 1930–31 Belgenland took part in successful tests of a long-range ship-to-shore radiotelephone. The Great Depression led IMM to cease her cruises around the World from 1931 and reduce her transatlantic crossings. That year she made six-day cruises and one-day trips from New York. In 1932 she made short cruises and at least one transatlantic crossing. In 1933 she made a Caribbean cruise and at least one transatlantic crossing. In 1934 she made European cruises from England, and then was laid up.

As Columbia in 1935 the ship ran Caribbean cruises: four in spring to the West Indies, and then four in summer to Panama and Venezuela. By autumn she was laid up again, and in 1936 she returned to Britain to be scrapped.

Belgenland was by far the largest ship Red Star Line ever owned. In her heyday she was the largest liner in transatlantic service between Antwerp and New York, and the largest liner to cruise around the World. As Columbia she was the largest ship then registered in the U.S.

Harland & Wolff built Belgenland. She shared the same hybrid propulsion system as several other H&W liners of her era including Laurentic and Justicia. However, she was a unique ship with no sister.[1] She had a reputation for stability in the worst North Atlantic weather, and for reliability.[2]

Belgenland had strong links with Belgium, although she was never registered there. Her more notable passengers included Eleanor Roosevelt in 1929, Douglas Fairbanks in 1931, and Albert Einstein in 1930 and 1933.

Building

[edit]IMM ordered Belgenland in March 1912[3] from Harland & Wolff, who built her on slipway number 1 as yard number 391. She was laid down before the First World War, but by the time she was launched on 31 December 1914 the war had been under way for four months. Work on her was suspended to let H&W concentrate on more urgent war-related work. As the Central Powers' U-boat campaign depleted Allied shipping, the need for replacement ships increased, and H&W resumed work on Belgenland. She was completed as a troop ship on 21 June 1917 and renamed Belgic.[4][5]

H&W planned Belgenland to have three funnels and two masts, and a passenger superstructure of several decks. For war service, however, she was completed as a cargo ship with two funnels and three masts, and without the two upper decks of her planned superstructure.[3][4][6] The extra mast enabled her to have more derricks, with which to handle cargo more quickly.[3] She was one of a number of ships that had been planned as liners but were part-completed at that time as cargo ships. H&W completed the similar but smaller Calgaric with one funnel and almost no superstructure, to serve as the wartime cargo ship Orca.

Belgic's registered length was 670.4 ft (204.3 m), her beam was 78.4 ft (23.9 m), her depth was 44.7 ft (13.6 m) and her draught was 36 ft 3 in (11.0 m).[7] Her holds included space for 44,400 cubic feet (1,257 m3) of refrigerated cargo.[8] As built, her tonnages were 24,547 GRT and 15,440 NRT.[7]

Belgic was one of a series of H&W steamships that were propelled by a combination of reciprocating steam engines and a steam turbine. She had three screws. A pair of four-cylinder triple expansion engines drove her port and starboard screws. Exhaust steam from those engines powered one low-pressure turbine that drove her middle screw.[7] H&W had used this arrangement first on Laurentic for White Star Line, and most notably on the three Olympic-class ocean liners. Between them, Belgic's three engines were rated at a total of 2,653 NHP[9] or 18,500 ihp[5] and gave her a speed of 17+1⁄2 knots (32.4 km/h).[4][10]

A photograph of the ship being fitted out in Belfast between 1915 and 1917 shows "Belgenland, Antwerpen" on her stern as her name and intended port of registration. However, German forces had captured Antwerp in October 1914. Hence when she was completed in 1917, Belgenland was transferred to White Star Line, renamed Belgic and registered in Liverpool.[7] Her United Kingdom official number was 140517 and her code letters were JQDG.[9]

Belgic 1917–22

[edit]White Star Line ran Belgic between Liverpool and New York under the direction of the UK Shipping Controller. On 11 August 1918 U-155 tried to attack her, but was unsuccessful.[11]

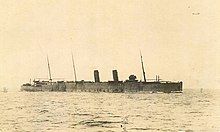

The ship is as completed in 1917, with two funnels and three masts. White Star Line is operating her, but her funnels seem to be in Red Star Line colours of black with a white band.

Later in 1918 Belgic was refitted as a troop ship. She had berths for 3,000 troops, but on one voyage she carried 3,141[11] and on another she carried 3,400.[2] She repatriated Allied troops after the Armistice of 11 November 1918. On 16 January 1919 she reached New York carrying 3,267 members of the American Expeditionary Forces. They included 240 men and 36 officers of the 49th Infantry Regiment, and some members of the 367th Infantry Regiment and 13th Aero Squadron.[12] On 16 August 1919 Belgenland left Liverpool carrying 3,400 servicemen home to Halifax, Nova Scotia and New York.[2]

By the middle of 1920, IMM was investigating recurrent instances of cargo disappearing from its ships. Disappearances had been happening for about two years, and cargo worth about $5 million appeared to have been stolen. When Belgic docked at Pier 16 on the North River in New York at the beginning of July 1920, White Star Line officials found that cloth worth about $60,000 was missing from her cargo.[13]

On the night of 2 July two NYPD detectives and three of IMM's own in-house detectives put Belgic under observation. At about 0200 hrs they saw several men descending her gangway carrying bundles of linen, tweed and other cloth. The detectives drew their revolvers and confronted the men. The men threw their bundles either ashore or into the water and fled back aboard.[13]

The detectives pursued the men aboard, and along the ship's companionways. The men were armed, and exchanged fire with the detectives. In total about 30 shots were fired. Other members of the crew tried to impede the detectives. Detectives chased one fugitive to the end of the pier, where he jumped into the water. An hour's search failed to find him, and he was presumed drowned.[13][14]

12 members of Belgic's crew were arrested and taken ashore.[13] Four of her engine room crew were suspected of stealing broadcloth worth about $1,000. They were charged with grand larceny and remanded for trial. The other eight were firemen who were charged with disorderly conduct and were released.[14]

From April 1921 Belgic was laid up in Liverpool, awaiting refitting. In March 1922 she returned to Belfast for Harland and Wolff to refit her as an ocean liner.[11]

Belgenland 1923–35

[edit]

Harland & Wolff increased her superstructure to four decks,[4] including a wide promenade deck that had a low rail and was enclosed with a glass screen, to give passengers an unobstructed view of the sea when seated in their low deckchairs.[15][16] Another glass screen separated her ballroom and first class dining saloon instead of a bulkhead. Other passenger comforts included a children's playground and an open air gymnasium. Third class public accommodation included space for dancing and a veranda café.[15]

Belgenland's first class dining saloon could seat 370 diners. 180 were at two-seat tables, and the remainder at four- and six-seat tables. Off the main dining saloon were private dining saloons, available for families or private entertaining. Forward of the dining saloon was a palm court with a grand piano. The ship had its own orchestra, which gave concerts in the palm court. Second class accommodation had a dining saloon with small tables, a loung, and a library.[17]

The New York Times claimed that the ship was fitted out with berths for 2,700 passengers, including 400 in first class.[15] Other sources state that she had berths for 500 passengers in first class, 500 second class and 1,500 third class.[4][5] However, as a result of the Emergency Quota Act that the United States Congress passed in 1921, and the Immigration Act of 1924 that followed it, Belgenland's third class accommodation was never fully used. Eventually the third class cabins on the after part of 'D' and 'E' decks were permanently closed down, and the third class cabins on 'D' deck amidships starboard were turned into catering department accommodation. The only third class cabins kept in passenger use were amidships on 'E' deck and amidships on the port side of 'D' deck.[2] On the forward part of 'C' deck, what had been the third class smoking room was converted into a laundry.[18]

H&W converted the ship from coal burning to oil, increased her funnels to three as originally planned, and reduced her masts to two.[11] Wireless direction finding was added to her navigation equipment. After the refit, her tonnages were reassessed as 27,132 GRT and 15,352 NRT. Her original name Belgenland was restored, but she remained registered in Liverpool.[19]

1923 transatlantic season

[edit]

Belgenland returned to service in 1923. Her transatlantic route was now between Antwerp and New York via Southampton.[4] Cardinal Mercier, Primate of Belgium, blessed her before she made her first departure from Antwerp as an ocean liner[20] on 4 April. On her first voyage she carried only 260 passengers, including 86 in first class. She reached New York on 14 April,[15] and left on 18 April on her return voyage to Antwerp.[21] On 11 July she left New York for Antwerp carrying 290 passengers in first class.[22] On 10 November 1923 she reached Ellis Island carrying 1,257 European migrants to the U.S., including 278 from the USSR.[23]

1924 Mediterranean cruise

[edit]

In May 1923 the British travel agency Thomas Cook & Son announced that it would charter Belgenland for a Mediterranean cruise. Despite her capacity for 2,500 passengers, Thomas Cook set a limit of 500,[24] and secured bookings for 420. Belgenland began the cruise on 19 January 1924, leaving New York for destinations including Palestine and Egypt. Passengers would have the option to see archæological sites including the Tomb of Tutankhamun,[25] whose recent discovery in November 1922 had inspired great popular interest in Egyptology.

1924 transatlantic season

[edit]By spring 1924 the Scheldt had silted up too much for Belgenland to reach Antwerp safely.[26] Red Star Line temporarily changed her European terminus to London.[11] In 1924 her route included calls at Cherbourg as well as Southampton,[27] plus Halifax, Nova Scotia from June to October, and Plymouth on eastbound voyages only.[28] The Scheldt was dredged,[11] and on 7 August Belgenland resumed sailings to Antwerp.[26]

When Belgenland left New York for Antwerp on 9 October 1924 her ports of call were to be Plymouth and Cherbourg.[29] On 20 November she ran aground on a mud bank in the Scheldt. She was briefly dry docked for her hull to be inspected, found to be undamaged, and continued her voyage to New York.[30]

In July 1924 there was another case of theft by members of the ship's crew. It was reported from Hamburg that 356 registered letters to addressees in Germany and Austria had been opened while in transit aboard Belgenland, and the contents of 328 of those letters had been stolen.[31]

1924–25 World cruise

[edit]

In 1924–25 Belgenland made her first cruise around the World. Her route was 28,310 miles, and would take 133 days to visit 60 cities in 14 countries. Fares were $2,000 for a single berth and $4,000 for a double suite. The best de luxe suites were $25,000 for four people and $40,000 for six. Gross fare income for this first cruise was about $2 million.[32]

Belgenland started from New York on 4 December 1924 carrying either 350 or 384 passengers (reports differ).[33] She visited Havana, where she loaded $80,000 worth of liquor, including 23,000 bottles of beer.[34] She then became the largest liner to pass through the Panama Canal.[35] She called at San Pedro, and embarked another 100 passengers in San Francisco. From there she crossed the Pacific via Honolulu to Yokohama, then went via Manila, Java and Singapore to the Indian Ocean. She was then to call at Port Sudan for her passengers to travel by rail to Khartoum, and also to Wadi Halfa to see the Second Cataract of the Nile.[36][37] At the time, Red Star Line claimed that Belgenland was the largest ship to have circumnavigated the globe.

The cruise also included a visit to Shanghai, scheduled for 27 January 1925. But when she arrived, the Chinese fort at Wusong had been firing at British shipping on the Huangpu River, so U.S. Navy Admiral Charles B. McVay Jr. sent the destroyer USS Borie to escort her safely in and out of port.[38] When Belgenland and Borie anchored in the river, the commander of Wusong fort ordered them to move out of his line of fire, which they did. That night a Royal Navy light cruiser joined Belgenland and Borie at their anchorage.[33]

Belgenland completed her cruise when she got back to New York on 15 April 1925. Only 235 of her passengers completed the circumnavigation.[33]

1925 transatlantic season

[edit]

Belgenland then resumed her transatlantic service between Antwerp and New York.[39] On 18 July she reached New York from Antwerp carrying only 269 passengers.[40] On 23 July she left again carrying only 320 passengers, of whom 122 were in first class.[41] On 12 September she docked in New York carrying 1,326 passengers.[42]

1925–26 World cruise

[edit]

On the night of 25–26 November Belgenland left New York on her second cruise around the World. She carried 400 passengers, including nine honeymooning couples.[43] Her route was 30,000 miles and scheduled to take 132 days. She was to repeat her previous year's route via Cuba, the Panama Canal and California, where she would embark another 75 passengers in San Francisco, and continue to Hawaii, Japan, China, Philippines, Java and Malaya. She would then visit India and Ceylon, pass through the Suez Canal, visit Egypt, Palestine, Italy and Gibraltar before returning across the Atlantic to New York,[44] where it arrived on 7 April 1926.[43]

1926 transatlantic season

[edit]After her cruise, Belgenland resumed her transatlantic service between Antwerp and New York.[45] On 12 September she docked in New York carrying 1,300 passengers.[46]

On 24 May 1926 Violet Jessop joined Belgenland's crew.[47] She had previously been a stewardess and nurse for White Star Line, and survived the sinking of both RMS Titanic in 1912 and HMHS Britannic in 1916, which earned her the nickname "Miss Unsinkable". Crew and passengers alike had a high regard for her.[48] She remained with Belgenland until 23 November 1931, and returned to the ship for summer cruises in 1932, '33 and '34.[49]

1926–27 World cruise

[edit]

On 14 December 1926 Belgenland left New York at the start of her third cruise around the World.[50] Her passengers included the lawyer Samuel Untermyer, who had suite 27–31 stripped of its Red Star Line furniture and refurnished with furniture from his own home for the duration of the cruise.[51]

She followed route similar to that of her previous two World cruises.[50] However, after she left Kobe the U.S. and UK consuls advised her via wireless telegraph to avoid Shanghai. At first it was reported that she would visit Hong Kong instead,[52] but instead she added a visit to Bangkok in Siam. Belgenland arrived back in New York on 24 April 1927, having covered 30,000 miles in 132 days and visited 23 ports in 15 countries.[53]

1927 transatlantic season

[edit]After her cruise, Belgenland resumed her transatlantic service between Antwerp and New York. On 6 May 1927, on the ship's first eastbound voyage that year, a woman passenger found that she had been robbed of jewels, cash and cheques worth a total of $12,000, and her passport.[54]

In 1927 IMM transferred ownership of Belgenland from Red Star Line to another subsidiary, Frederick Leyland & Co.[55][56] Red Star Line continued to manage her.

On 5 December on a westbound crossing, a heavy sea swept over her starboard bow, smashing the iron standard supporting her ship's bell on Belgenland's forecastle and a ventilator to her crew's galley. When she reached New York a new standard was installed, and her bell, which weighed 200 lb (91 kg), was re-hung.[57]

1927–28 World cruise

[edit]On the night of 13–14 December 1927 Belgenland left New York carrying 350 passengers on her fourth cruise around the World. Her itinerary had been increased to 28 ports. Bangkok, where she made an unscheduled extra call in January 1927, now became part of her scheduled itinerary. Also newly added were Miyajima, Formosa and Piraeus.[58] When she got back to New York on 26 April 1928 the ship was carrying 138 of her original passengers, plus 120 others who had embarked at Mediterranean ports.[59]

1928 transatlantic season

[edit]

Belgenland almost immediately returned to her transatlantic service, leaving New York on 3 May 1928 for Antwerp.[60] In June she took a cargo of grain and general cargo from the U.S. to Antwerp. She was unable to complete discharging it in Antwerp, as Belgian stevedores went on strike. On 21 June she left Antwerp on her next westbound voyage with some of the cargo still aboard.[61] She discharged her general cargo in Southampton, and on 1 July reached New York. She was to land her grain in London if the strike in Antwerp continued.[62]

1928–29 World cruise

[edit]On the night of 17–18 December 1928 Belgenland left New York with 300 passengers at the start of her fifth cruise around the World. She followed her usual westbound route, and was scheduled to pass through the Panama Canal on Christmas Day 1928, and to embark another 175 passengers in San Francisco on 5 January 1929.[63][64] One passenger took with him his own 15 ft (5 m) motorboat.[65] The cruise lasted until 1 May 1929, when the ship arrived back in New York.[66]

On 2 January 1929 a Federal grand jury in New York indicted two men with conspiracy to smuggle diamonds into the Port of New York. One of the accused was described as a petty officer from Belgenland. The other was a jeweller from The Bronx.[67]

In 1928 the popularity of "tourist-third cabin class" berths on transatlantic liners increased. At the end of January 1929 IMM announced that it would convert the second class accommodation aboard the Red Star liners Belgenland and Arabic to tourist third class. The company said Belgenland would be converted after her return from her cruise around the World, with her 500 second class berths being replaced by 600 tourist-third class berths. Electric elevators would be installed, and her staterooms were to have running hot and cold water.[68]

1929 transatlantic season

[edit]

Belgenland resumed her transatlantic service on 4 May 1929, leaving New York for Antwerp via Plymouth and Cherbourg.[69] That September her westbound passengers included Eleanor Roosevelt, her sons Franklin Jr and John II, and friends Nancy Cook and Marion Dickerman. Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt came with a motorcycle escort to meet the ship when she reached New York on 15 September.[70]

1929–30 World cruise

[edit]On 20 December 1929 Belgenland left New York carrying 375 passengers at the start of her sixth cruise around the World.[71] She reached Havana on Christmas Day.[72] On 28 December she set a record by passing through the Panama Canal in only seven hours. At that time a normal passage through the canal took eight or nine.[73]

1930 transatlantic season

[edit]By 1930 Belgenland's wireless telegraphy call sign had been changed to GMQJ.[74] When Belgenland left New York for Antwerp on 23 August 1930, her passengers included the gangster Legs Diamond, travelling under the false name of John Nolan.[75] The NYPD suspected that he might have left the U.S. aboard RMS Olympic or RMS Baltic, but he was not found on either ship when they reached Europe. The NYPD then sent a wireless telegraph message to Belgenland, which replied that a man answering Diamond's description was among her passengers.[76]

The NYPD telegraphed the police in Plymouth, Cherbourg and Antwerp, warning them that he was an undesirable character.[76] When Belgenland reached Plymouth on 31 August, Scotland Yard officers told Diamond he would not be allowed to land in England.[75] He disambarked in Antwerp on 1 September. Belgian police expelled him as an undesirable alien to Germany, where police in Aachen arrested him.[77]

1930–31 World cruise

[edit]Radiotelephone experiment

[edit]When Belgenland left Antwerp for New York on 2 December 1930, AT&T announced that she would test experimental radiotelephone equipment. It was intended link the ship with Bell System telephones in the U.S., Canada, Cuba and Mexico, and via shortwave radio to GPO telephones in the UK.[78] Four AT&T employees travelled on the ship to operate the equipment.[79]

On 18 December AT&T connected Belgenland's radio telephone to New York, whence the call was routed by landline to Buenos Aires. The voice communication over a distance of 6,500 miles was reported to be "unusually clear".[80]

In February Belgenland was off the coast of China between Shanghai and Hong Kong when AT&T connected her radiotelephone to London, more than 7,000 miles away.[81] On 2 April she was in the Red Sea when AT&T successfully connected her radiotelephone to New York, about 6,000 miles away.[82] Another call was connected between the ship and a telephone customer in Piedmont, California, a distance of about 9,000 miles, but AT&T did not state whether this was by radio all the way to California.[83]

The longest radiotelephone connection made on Belgenland's voyage was between Colombo and Australia via Imperial Wireless Chain stations in England, a distance of about 18,000 miles. Signals were received at Rugby Radio Station in Warwickshire, and transmitted from Baldock in Hertfordshire. During the cruise a total of 200 radiotelephone calls were made between the ship and telephone customers all around the World.[79]

Albert and Elsa Einstein

[edit]Passengers who joined Belgenland in Antwerp included Albert and Elsa Einstein, who were travelling to the U.S. for a holiday.[84] The ship reached New York on 11 December, and left on 15 December to start her next cruise westbound around the World. When the cruise started, the Einsteins remained aboard as far as California, to visit friends.[85]

On 19 December Belgenland docked in Havana. Several thousand Cuban Jews gathered to welcome Einstein to the Havana Jewish Centre, including a choir of schoolchildren who sang Hatikvah and La Bayamesa to him.[86]

On 23 December Belgenland passed through the Panama Canal. The next day the Einsteins used the radiotelephone to broadcast a Christmas greeting to the people of the U.S. via the Western Electric and ABC Radio networks. The Professor spoke in German, which his wife translated into English.[87]

Douglas Fairbanks and Victor Fleming

[edit]Belgenland called at Los Angeles on 1 January and San Francisco two days later. She left California with 303 passengers, which included a record number of embarkees from the Pacific coast. The ship made each of her cruises around the World in association with American Express. When she left San Francisco, she carried 27 of the company's staff to serve the passengers.[88]

Passengers who joined Belgenland in Los Angeles included actor Douglas Fairbanks, who planned visits to Japan, Siam and India followed by a hunting tour of French Indochina.[89] With him was the film director Victor Fleming. On the voyage they started filming the documentary Around the World in 80 Minutes with Douglas Fairbanks.[90]

On 15 January, four days after the ship left Honolulu, Fairbanks spoke via radiotelephone with his wife Mary Pickford in New York. AT&T routed the call via its shortwave station at Ocean Gate, New Jersey, a distance of about 7,400 miles.[91] Later that month, when the ship was off Yokohama, Fairbanks spoke via radiotelephone with friends in San Francisco, a distance of about 10,000 miles.[82]

Homecoming

[edit]In Naples or Monaco many of Belgenland's original passengers disembarked to tour in Europe, and other passengers joined to sail to New York. The ship called also at Antwerp, where she loaded 1,650 tons of silver sand as ballast. She reached New York on 28 April 1931 carrying 172 of her original passengers.[79]

1931 showboat cruises

[edit]After her cruise, Belgenland resumed her transatlantic service between Antwerp and New York on 30 April 1931.[79] But this was only until 18 July, when Red Star Line switched her to a series of five weekly "showboat cruises". The ship left New York each Saturday, staged a different Broadway theatre entertainment every night, and spent two days in Nova Scotia before returning.[92]

For her showboat cruises Belgenland was equipped with a "Lido Beach", with two open-air swimming pools, beach chairs and 6,000 square feet (557 m2) of white sand[93] from the beach at Ostend[94] forming a beach several feet deep.[95] The lido was on her tourist class promenade deck, which was part of 'A' deck. The pools were fore and aft of her mizzen mast.[94] They were made by removing two hatch covers, and letting a large canvas bag down through each hatch to the hatch cover on the deck below, which was reinforced with timber to bear the weight of the water. Each pool had to be emptied daily, a deck-hand would scrub it clean, and the pool would then be refilled with a hose.[96]

Belgenland faced competition on the New York – Halifax cruise route from United States Lines' Leviathan and White Star Line's Olympic and Majestic. Cunard Line was also sending its liners on short cruises between transatlantic crossings.[97]

Being registered in the UK, Belgenland was exempt from U.S. alcohol prohibition law when outside U.S. territorial waters. For her showboat cruises she had a large bar on her quarterdeck serving refrigerated lager.[98] Fares for each six-day cruise started from $70 per passenger, inclusive of all meals. All liquor was extra, and it was from these sales that the cruises made much of their profit.[99]

There were cases of prostitution on the showboat cruises. Red Star Line blacklisted any passenger whom it found to be working as a prostitute.[99]

Belgenland already had her own palm court orchestra, which was a Belgian quintet who specialised in chamber music, but also played for balls and church services.[96] For her first showboat cruise on 18 July she added a 14-piece big band and embarked entertainers including Lester Allen, Johnny Burke, Arthur "Bugs" Baer, Milt Gross, Harry Hershfield and Claire Windsor.[100] For her 18 July cruise Belgenland embarked 700 passengers, 75 per cent of whom were women.[98]

The second showboat cruise left New York on 25 July.[101] The third showboat cruise, which left New York on 1 August, again attracted 700 passengers.[102] On one cruise, entertainers included the harmonica virtuoso Larry Adler.[94]

Typhoid cases

[edit]Three of Belgenland's showboat cruise passengers developed typhoid after they returned home, and one of them died in the French Hospital in Manhattan. The New York City Department of Health asked the United States Public Health Service to help its investigation.[103] Westchester County Department of Health found that before the cruise that began on 8 August, an assistant cook on the ship had also contracted typhoid. He had been removed from the ship, and later died.[104]

Fujimura disappearance

[edit]On the fourth showboat cruise, which left New York on 8 August, the entertainers included Mildred Harris, former wife of Charlie Chaplin. The passengers included a Japanese merchant called Hisashi Fujimura of Norwalk, Connecticut, and his seven-year-old daughter. With them were Fujimura's mistress Mary Reissner, formerly a showgirl with the stage name Mary Dale, who was posing as his daughter's governess.[105][106] Fujimura headed Asahi Corp, which had premises on Madison Avenue, New York, and was one of the biggest U.S. importers of silk.[107]

As Belgenland was returning to New York on the morning of 14 August, Fujimura was reported missing. He was seen at 0100 hrs that morning, when the ship was east of Fire Island,[105][106] and the ship's Master, Captain JH Doughty, later said he saw him at 0245 hrs.[108] United States Coast Guard Cutters searched unsuccessfully for Fujimura's body in waters beyond the Ambrose Lightship.[105][106]

U.S. Attorney George Z. Medalie ordered Assistant U.S. Attorney J. Edward Lumbard to investigate. Lumbard questioned Mary Reissner on at least two occasions,[109] and once questioned Mildred Harris.[110] Another Assistant U.S. Attorney, Edward Aronow, questioned a convicted extortionist serving a sentence in Suffolk County Jail on Long Island, who was a close friend of Fujimura.[111] The extortionist was said to know a chauffeur whom Fujimura had recently dismissed.[112]

Fujimura had several life insurance policies, with a total value of $290,000. One was a $50,000 policy that he had only recently taken out. Another was a $20,000 policy whose beneficiary he had changed from his estate to his wife the day before Belgenland sailed.[113]

For several months, Fujimura had had $335,412 on deposit in the Bank of Manhattan Trust Company. All but $2 of this sum was withdrawn on 8 August, the same day that Fujimura sailed on Belgenland. $100 was deposited in the same account sometime after the sailing. He had also begun a lawsuit before Justice John F. Carew in the New York Supreme Court to recover $40,000 from a company based in Madison Avenue. The case was outstanding when Fujimura disappeared.[114] Between 1 and 8 May, Fujimura had paid out $229,000 to four men, apparently to settle gambling debts.[115]

During the investigation Reissner received two letters demanding $5,000, which led the NYPD to question a man and a woman on suspicion of blackmail. Aronow said he believed that two men, posing as United States Department of Justice officers, had tried to blackmail Fujimura, and had threatened to have him prosecuted under the Mann Act.[116]

On 21 August Belgenland reached New York at the end of her sixth showboat cruise, and resumed her transatlantic service the same day. FBI investigators were aboard throughout the nine hours she was in port.[108]

On 8 September, Medalie announced that the investigation had been completed "for all practical purposes", and had failed to show that Fujimura had been murdered.[117] However, on 5 October an electrician working at an apartment in West 35th Street found an empty black leather wallet with "Hasashi Fujimura" (sic) stamped on it in gold letters, and handed it in to the NYPD.[118]

Fujimura's widow returned to Okayama in Japan, taking their four young children. His estate was not settled until 1935. Debts and expenses totalling $554,937 wiped out his assets of $538,133.[107]

1931 day trips

[edit]On 12 October 1931 Belgenland took 1,647 passengers on a day trip for Columbus Day, leaving at 0900 hrs and returning at 2300 hrs. The White Star liner RMS Homeric did the same with 1,009 passengers.[119] On 22 October Majestic made a similar day trip with nearly 500 passengers.[120] As UK-registered ships, the three liners were able to serve alcohol as soon as they were outside the U.S. territorial limit. Dining room service was continuous. Catering Department staff were briefed that they would have no meal breaks, and should make sandwiches or fill rolls for themselves in advance so that they could work continuously all day.[121]

Supporters of prohibition alleged that the day trips violated the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and the Volstead Act. They alleged that the UK-registered ships were, in effect, engaging in U.S. coastal trade, which violated a protectionist agreement between the U.S. and UK. They wrote to Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, calling for Belgenland to be seized and fined.[122]

1931 transatlantic season

[edit]In autumn 1931 Belgenland returned to transatlantic service. That October she carried a consignment of gold bullion from New York to Le Havre. Her holds were rarely full, but that November she crossed from New York and Halifax to Antwerp with her cargo holds filled to the hatch covers with barrels of apples bound for Antwerp and London.[48]

1932 short cruises

[edit]Belgenland did not make a 1931–32 cruise around the World, as by then several newer and more luxurious liners were competing for that trade.[123] Instead Red Star Line planned to send her on six cruises to the West Indies, leaving New York twice a month from 20 January 1932 until 5 April. But too many transatlantic liners were competing for cruises at the same time, flooding the market, so Red Star cancelled all of Belgenland's cruises.[124]

On 17 June 1932 Belgenland left Antwerp on the same day as another Red Star liner, Westernland. Belgenland carried cargo but no passengers and only a skeleton crew.[125] On 27 June the two ships reached New York, where Belgenland was to remain to resume cruising.[126] In New York her crew was made up to a full complement by the addition of U.S. seafarers, and on 1 July she left New York for a short cruise to Bermuda.[125]

Thereafter Belgenland made a series of weekly six-day cruises. Each Saturday she left New York at noon. She would spend the Monday in Halifax, the Wednesday in Bermuda, and get back to New York at 0900 on Friday morning. This gave her crew a very short time between trips to clean all her cabins, kitchens and public rooms, take on water and victuals, bunker her, and embark the next set of passengers.[125]

The cruises continued until at least mid-August,[127] but there were too few bookings for Belgenland to make all the cruises that had been advertised. She was laid up in New York, and the US members of her crew were paid off, and the British and Belgian members were put on half pay.[125]

On 2 September Belgenland reached New York and left the next day to start another short cruise,[128] which took 850 passengers on a four-day round trip to Bermuda.[129] After her return she was laid up. 340 of her crew sent home to Antwerp aboard Pennland when she left New York on 9 September. Pennland's third-class accommodation was reopened specially to carry Belgenland's crew, who were paid off when she reached Antwerp on 20 September.[129]

A skeleton crew of 21 officers, engineers and men remained to look after Belgenland. Red Star Line hoped that she could resume work in the winter cruising season.[130]

A New York socialite, Dorothy Clark, chartered Belgenland to raise funds for the Frontier Nursing Service in Kentucky. On 14 January 1933 she held a supper dance aboard the laid-up ship in New York.[131] The dance generated interest for a 15-day Caribbean cruise aboard Belgenland to Cristóbal, Colón, La Guaira, Curaçao and Kingston, Jamaica.[132] The cruise began from New York on 25 February. Passengers included Mary Breckinridge, founder of the Frontier Nursing Service.[133]

The Einsteins flee Nazism

[edit]

After her charity cruise, Belgenland made at least one transatlantic crossing. On 18 March 1933 she left New York[134] for Antwerp via Le Havre with passengers including Albert Einstein,[135] who planned to return home to Germany. However, on 23 March the Reichstag passed the Enabling Act of 1933, which turned Germany into a Nazi dictatorship. While still at sea, Einstein received news that the Nazis had raided his summer home at Caputh.[136] When Belgenland reached Antwerp on 28 March, he disembarked and changed his destination to London, declared he had "no intention of ever returning to Germany",[137] and renounced his German citizenship.[138] In October 1933 the Einsteins emigrated to the United States.[84]

1933 Mediterranean cruises

[edit]From 28 July 1933 Belgenland made three 14-day cruises from Tilbury to the Mediterranean. Each cruise visited Gibraltar, Monte Carlo, Corsica, Elba, Civitavecchia (for Rome), Naples, Valletta, Tunis, Ceuta and Vigo. Belgenland was too big to dock at Monte Carlo, so she anchored off-shore and tenders took passengers to and from the shore. She bunkered from an oil tanker in Civitavecchia. Her route from Civitavecchia to Valletta took her past Capri and through the Strait of Messina, for her passengers to see Stromboli at night and Mount Etna.[139] After the third cruise her crew was paid off on 23 September[49] at Tilbury and she was laid up.[140]

1934 Mediterranean cruises

[edit]From 25 July to 14 September 1934 Belgenland made another series of cruises from Tilbury to the Mediterranean.[49][141] Each cruise visited Algiers, Istanbul and Piraeus (for Athens).[142] She was then laid up again at London,[93] probably at Tilbury.

Columbia 1935–36

[edit]On 18 December 1934 IMM announced that it would transfer Belgenland to its Panama Pacific Line subsidiary, renamed her Columbia, and transfer her to the U.S. shipping register. IMM intended her to make a series of cruises from New York to Nassau, Bahamas, Miami and Havana, carrying up to 900 passengers.[93] Each cruise was to be for 11 days, and fares started at $125 per person.[143] The first cruise was scheduled to leave New York on 16 February 1935.[144] This was planned to be the first of a season of six similar cruises.[145]

300 men spent a month cleaning and renovating Belgenland in England.[146] Her hull was repainted light grey.[142] She left Tilbury under a British skeleton crew on 10 January 1935[143][146] and reached New York on 21 January.[147] Her port of registration was legally changed to New York and her name was changed to Columbia at the Custom House on 22 January,[148] making her the largest U.S.-registered merchant ship.[149] She was given the U.S. official number 233677 and wireless call sign WLFG. Her tonnages were reassessed as 24,578 GRT and 13,130 NRT.[150]

Captain Johan Jensen was appointed as Columbia's Master. His previous commands included Atlantic Transport Line's Minnekahda from 1921 to 1931, followed by United States Lines' President Roosevelt. A crew of more than 500 officers and men was signed on.[151] At the beginning of February a deckhouse on "A" Deck, which separated Belgenland's two swimming pools, was removed. This made room for one of the pools to be enlarged for adults, and the other to be adjusted to a depth of 3 feet (1 m) for children.[152] The beach café was named the Crow's Nest.[153] 439 leather-backed chairs from the ship were put into storage, and replaced by 425 satin-covered rosewood chairs were borrowed from Leviathan, which at that time was laid up.[154]

1935 spring cruises

[edit]On 16 February 1935 Columbia left New York on her first cruise to Nassau, Miami and Havana. For the 11-day voyage she carried more than 600 passengers, including IMM Chairman Philip Franklin.[155] When she began her second cruise on 2 March, she was carrying fewer than 400 passengers.[156] Her next sailing was on 16 March. Due to unrest in Cuba, her itinerary was changed to avoid Havana and call at Kingston, Jamaica instead. This added 700 miles to her voyage, but her departure and arrival times at New York stayed the same.[157]

On her fourth cruise Columbia carried only 285 passengers.[143][154] The fifth and sixth cruises where cancelled,[158] and when she reached New York on 10 April at the end of her fourth cruise she was laid at her pier in the North River. The rosewood chairs were returned to Leviathan, Columbia's leather-backed chairs were brought out of storage, and Captain Jensen returned to his previous command of President Roosevelt.[154]

1935 summer cruises

[edit]In May 1935 National Tours, Inc. chartered Columbia for a series of four cruises to the West Indies, Panama and Venezuela. The first and third were to start from New York on 6 July and 3 August and visit Saint Thomas, Curaçao, La Guaira, Colón, the Panama Canal, and Kingston, Jamaica. The second and fourth were to start on 20 July and 17 August and visit Port-au-Prince, Puerto Colombia, Colón and Kingston.[153] Each cruise was to be for 13 days, and the fare was $145 per passenger.[143]

The first cruise carried 500 passengers, and the second carried either 600[159] or 535 (reports differ).[160]

In 1933 the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution had repealed the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. When Columbia returned to New York on 2 August, about 90 per cent of her passengers brought liquor home with them.[160] She completed the series of four cruises at the end of August[161] and was then laid up again.[162]

Laid up and scrapped

[edit]In June 1935 the regulations for merchant ships registered in the U.S. were revised, and IMM estimated that to pass an inspection by the newly reorganised Bureau of Navigation and Steamboat Inspection it would cost between $250,000 and $500,000 to modify Columbia, which would make the ship unprofitable. IMM said she could still be operated profitably if registered in the UK, but the company would not countenance doing so.[149]

By September 1935 Columbia was laid up, initially at a pier in the North River,[163] and then at Hoboken, New Jersey.[149] On 12 February 1936 IMM put her up for sale for scrap,[143][163] and a month later Douglas & Ramsey of Glasgow bought her,[149] reportedly for $275,000.[143] On 22 April she left New York with a skeleton crew.[164] She crossed the Atlantic for the final time and on 4 May 1936 she arrived off Bridgeness Pier at Bo'ness on the Firth of Forth.[143] On 22 May she left her anchorage and was run aground at high tide under her own power at P&W MacLellan's yard to be scrapped.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ "Events of interest in shipping world". The New York Times. 29 March 1936. p. 103. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c d Finch 1988, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Finch 1988, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f "Belgic". Harland and Wolff Shipbuilding and Engineering Works. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "Belgic". Shipping and Shipbuilding. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ LeDuc 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Lloyd's Register 1917, II, B.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1917, I.

- ^ Harnack 1930, p. 442.

- ^ a b c d e f LeDuc 2010, p. 16.

- ^ "3,267 troops on Belgic". The New York Times. 17 January 1919. p. 11. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c d "Twelve arrested for looting ship". The New York Times. 3 July 1920. p. 6. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Hold 4 of Belgic's crew". The New York Times. 4 July 1920. p. 7. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c d "Belgenland here on maiden voyage". The New York Times. 15 April 1923. p. 4. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Wilson 1956, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Van Ravels, Jean-Marc. "Belgic IV / Belgenland II". Red Star Line. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Finch 1988, p. 109.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1923, BEL.

- ^ Wilson 1956, p. 38.

- ^ "Builder to return on the Belgenland". The New York Times. 18 April 1923. p. 6. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Baron de Cartier sails for Belgium". The New York Times. 11 July 1923. p. 22. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgian and Swiss quotas exhausted". The New York Times. 11 November 1923. p. 4. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgenland Chartered for Cruise". The New York Times. 14 May 1923. p. 18. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Throngs go abroad on 5 liners today". The New York Times. 19 January 1924. p. 14. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Ocean travel". The New York Times. 7 August 1924. p. 15. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Thousands leaving on today's ships". The New York Times. 5 April 1924. p. 25. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Larsson, Björn (23 June 2019). "Red Star Line". marine timetable images. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Ocean travel". The New York Times. 9 October 1924. p. 23. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgenland Suffered No Damage". The New York Times. 23 November 1924. p. 15. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Mail to Germany robbed". The New York Times. 16 July 1924. p. 4. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Finch 1988, p. 104.

- ^ a b c "Returned tourists got a taste of war". The New York Times. 16 April 1925. p. 5. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Finch 1988, p. 106.

- ^ Finch 1988, p. 103.

- ^ "Belgenland ready for World cruise". The New York Times. 4 December 1924. p. 12. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Food by the ton for World cruise". The New York Times. 11 January 1925. p. 76. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "To guard Belgenland in Shanghai harbor". The New York Times. 26 January 1925. p. 4. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Tourists off today on the Belgenland". The New York Times. 28 May 1925. p. 12. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "7,000 to sail today on ten steamships". The New York Times. 18 July 1925. p. 19. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Woman boards a tug to win race with ship". The New York Times. 24 July 1925. p. 6. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Dutch editor held after trip abroad". The New York Times. 13 September 1925. p. 12. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Belgenland back from World cruise". The New York Times. 8 April 1926. p. 6. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Liner sails today for World cruise". The New York Times. 25 November 1925. p. 34. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Nine liners head for Europe today". The New York Times. 26 June 1926. p. 25. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Blind girl tells of tour in Europe". The New York Times. 13 September 1926. p. 12. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Jessop 1997, p. 229.

- ^ a b Finch 1988, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Jessop 1997, p. 230.

- ^ a b "Liner tales many on World cruise". The New York Times. 14 December 1926. p. 47. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Untermyer goes soon on round-World tour". The New York Times. 5 December 1926. p. 26. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Drops Shanghai From World Cruise". The New York Times. 1 February 1927. p. 15. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgenland in port from World cruise". The New York Times. 25 April 1927. p. 47. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Miss M. L. Pillot is Robbed on a Liner Of Jewels and Money Valued at $12,000". The New York Times. 9 May 1927. p. 23. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1927, BEL.

- ^ "Two ships in late because of storms". The New York Times. 13 December 1927. p. 59. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Sails on World cruise". The New York Times. 13 December 1927. p. 29. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgenland arrives from World cruise". The New York Times. 27 April 1928. p. 29. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Five ships sail for Europe today". The New York Times. 3 May 1928. p. 30. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Antwerp dockers strike". The New York Times. 22 June 1928. p. 12. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Barred grain back in ship". The New York Times. 2 July 1928. p. 20. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Will start round World". The New York Times. 16 December 1928. p. 77. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgenland off on World cruise". The New York Times. 18 December 1928. p. 63. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Americans shun wine on Belgenland cruise". The New York Times. 5 May 1929. p. 26. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Crew get back souvenirs". The New York Times. 4 May 1929. p. 39. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Two Indicted in Diamond Smuggling". The New York Times. 3 January 1929. p. 23. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Will refit liners for tourist third". The New York Times. 1 February 1929. p. 51. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Eight ships to sail for foreign ports". The New York Times. 4 May 1929. p. 12. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Mrs. Roosevelt back from European tour". The New York Times. 16 September 1929. p. 21. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Bishop Dunn on cruise". The New York Times. 21 December 1929. p. 5. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Liner at Havana on World Cruise". The New York Times. 27 December 1929. p. 47. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgenland makes record at Panama". The New York Times. 31 December 1929. p. 25. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "'Legs' Diamond Is Aboard Liner Belgenland Wants to Go to Vichy to "Take Cure," He Says". The New York Times. 1 September 1930. p. 1. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "British keep watch for 'Legs' Diamond". The New York Times. 31 August 1930. p. 14. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Germans Seize 'Legs' Diamond After Expulsion From Belgium". The New York Times. 2 September 1930. p. 1. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Cruise to test telephone". The New York Times. 3 December 1930. p. 50. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c d "Belgenland is back from World cruise". The New York Times. 29 April 1931. p. 51. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Talk to ship in radio test". The New York Times. 20 December 1930. p. 37. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Sets sea phone record". The New York Times. 8 January 1931. p. 52. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Belgenland in today from World cruise". The New York Times. 28 April 1931. p. 55. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Phone 9,000 miles to liner". The New York Times. 3 April 1931. p. 51. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Albert Einstein, a Famous Passenger". Red Star Line Museum. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Einstein asks press not to use ship phone". The New York Times. 3 December 1930. p. 15. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Einstein Deeply Moved by Welcome of Havana Jews". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 24 December 1930. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Einstein heard on radio". The New York Times. 25 December 1930. p. 20. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Big World tourist list". The New York Times. 8 January 1931. p. 47. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Fairbanks off for tour". The New York Times. 2 January 1931. p. 29. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Douglas Fairbanks". Red Star Line Museum. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Telephones 7,400 miles". The New York Times. 16 January 1931. p. 23. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "'Showboat cruises' begin here July 18". The New York Times. 15 April 1931. p. 21. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c "Belgenland joins U.S. trade fleet". The New York Times. 19 December 1934. p. 45. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c Finch 1988, p. 113.

- ^ Wilson 1956, p. 208.

- ^ a b Finch 1988, p. 114.

- ^ "White Star to run trips to Halifax". The New York Times. 17 June 1931. p. 17. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "700 on show boat cruise". The New York Times. 19 July 1931. p. 21. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b Finch 1988, p. 116.

- ^ ""Show boat" sailing fete". The New York Times. 17 July 1931. p. 37. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Friars off today on Halifax cruise". The New York Times. 25 July 1931. p. 17. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Untermyer sailing on trip to Europe". The New York Times. 1 August 1931. p. 7. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Three typhoid cases found after cruise". The New York Times. 5 September 1931. p. 15. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Links cook to typhoid". The New York Times. 6 September 1931. p. 16. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c "People". Time. 31 August 1931. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "Wealthy Japanese missing from liner". The New York Times. 18 August 1931. p. 23. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Fujimura estate here not taxable". The New York Times. 1 May 1935. p. 14. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Fujimura a suicide, ship's crew theory". The New York Times. 22 August 1931. p. 2. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Fujimura inquiry pressed". The New York Times. 24 August 1931. p. 3. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Medalie aide sifts the Fujimura case". The New York Times. 20 August 1931. p. 16. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Aids in Fujimura case". The New York Times. 28 August 1931. p. 2. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "To question Collins on Fujimura". The New York Times. 4 September 1931. p. 12. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Altered insurance a Fujimura clue". The New York Times. 21 August 1931. p. 21. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Bank deals deepen Fujimura mystery". The New York Times. 23 August 1931. p. 11. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Question Fujimura driver". The New York Times. 1 September 1931. p. 17. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Say extortion gang killed Fujimura". The New York Times. 29 August 1931. p. 9. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Say extortion gang killed Fujimura". The New York Times. 9 September 1931. p. 11. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Finds possible Fujimura clue". The New York Times. 6 October 1931. p. 22. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "2,656 sail to 'nowhere.'". The New York Times. 13 October 1931. p. 43. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Majestic off on 24-hour cruise". The New York Times. 22 October 1931. p. 47. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Finch 1988, pp. 112–113.

- ^ "Wants cruise ships seized for liquor". The New York Times. 23 October 1931. p. 47. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Finch 1988, p. 112.

- ^ "Ships cancel more winter trips". The New York Times. 30 December 1931. p. 39. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c d Finch 1988, p. 120.

- ^ "Liner arrives with no passengers". The New York Times. 28 June 1932. p. 43. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Lingers on Ship, Gets Voyage". The New York Times. 20 August 1932. p. 27. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "6,000 leave today on holiday cruises". The New York Times. 2 September 1932. p. 20. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b Finch 1988, p. 121.

- ^ "Liner France may quit". The New York Times. 10 September 1932. p. 31. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Debutantes dance on the Belgenland". The New York Times. 15 January 1933. p. 65. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Frontier service to gain by cruise". The New York Times. 19 February 1933. p. 73. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Charity tour tomorrow". The New York Times. 24 February 1933. p. 13. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Mrs. Taft to sail for Europe today". The New York Times. 18 March 1933. p. 10. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Einstein ruges Jews to stand together". The New York Times. 24 March 1933. p. 3. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Albert Einstein Renounces German Citizenship; "I Will Not Be Returning to Germany, Perhaps Never Again"". Shapell Manuscript Foundation. 28 March 1933. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ "Prof. Einstein hopes for curbs on Nazis". The New York Times. 28 March 1933. p. 11. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Einstein to alter status". The New York Times. 30 March 1933. p. 13. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Finch 1988, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Finch 1988, p. 123.

- ^ "Events of interest in shipping world". The New York Times. 7 October 1934. p. 37. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b Finch 1988, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f g Finch 1988, p. 98.

- ^ "Columbia cruise is set for Feb. 16". The New York Times. 23 December 1934. p. 81. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Liner to be withdrawn". The New York Times. 6 April 1935. p. 33. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "British are stirred as Belgenland sails". The New York Times. 11 January 1935. p. 47. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Belgenland Here for Transfer". The New York Times. 22 January 1935. p. 39. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Cruise liner is renamed". The New York Times. 23 January 1935. p. 36. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c d "Liner Columbia sold for junk". The New York Times. 27 March 1936. p. 45. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1935, COL.

- ^ "500 men get jobs on liner Columbia". The New York Times. 18 January 1935. p. 45. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "News of interest in shipping world". The New York Times. 17 February 1935. p. 78. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Columbia to make trips to tropics". The New York Times. 19 May 1935. p. 35. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b c "Cruise liner laid up". The New York Times. 11 April 1935. p. 45. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Ocean travelers". The New York Times. 16 February 1935. p. 10. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "O'Briens Sail on Cruise". The New York Times. 3 March 1935. p. 84. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Ships to avoid Havana". The New York Times. 12 March 1935. p. 6. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Liner to be withdrawn". The New York Times. 12 March 1935. p. 33. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "500 back from cruise". The New York Times. 20 July 1935. p. 3. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Tourists bring in liquor". The New York Times. 3 August 1935. p. 27. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Ocean travelers". The New York Times. 17 August 1935. p. 16. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Notes of interest to shipping world". The New York Times. 8 September 1935. p. 101. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Liner Columbia for sale". The New York Times. 27 February 1936. p. 41. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Columbia on Last Voyage". The New York Times. 23 April 1936. p. 47. Retrieved 9 July 2022 – via Times Machine.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bonsor, NRP (1975). North Atlantic Seaway. Vol. 2. Jersey: Brookside Publications. p. 859. ISBN 978-0905824017.

- Finch, Vernon EW (1988). The Red Star Line. Antwerp: Uitgeverij de Branding NV. ISBN 90-72543-01-7.

- Harnack, Edwin P (1930) [1903]. All About Ships & Shipping (4th ed.). London: Faber and Faber.

- Jessop, Violet (1997). Maxtone-Graham, John (ed.). Titanic Survivor. Dobbs Ferry: Sheridan House. ISBN 978-1574-090352.

- LeDuc, Martin (2010) [2009]. "Belgic IV (1917-36)". White Star Liners (PDF). Nanaimo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Lists of vessels fitted with refrigerating appliances". Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I–Sailing Vessels, Owners, &c. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1917. Part I.—List of vessels having a capacity of 80,000 cubic feet and over, and including all vessels holding Lloyd's R.M.C. – via Internet Archive.

- "Supplement". Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. II–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1917 – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. II–Steamers & Motor Vessels. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1923 – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. II–Steamers and Motorships. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1927 – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. II–Steamers and Motorships of 300 Tons Gross and Over. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1935 – via Internet Archive.

- Mercantile Navy List. 1918 – via Crew List Index Project.

- Mercantile Navy List. 1928 – via Crew List Index Project.

- Mercantile Navy List. 1930 – via Crew List Index Project.

- Wilson, RM (1956). The Big Ships. London: Cassell & Co.

External links

[edit]- "Belgenland-Red Star Line". Renato's World. Blogger. – menu cards from 1928–29 World cruise

- "Belgic IV / Belgenland". Great Ships. Jeff Newman – via Mark Baber. – Red Star Line colour postcards

- "Modelship Belgenland II". Red Star Line Museum. – cross-sectional model in a museum in Antwerp

- "Pictures Belgenland". Red Star Line. Jean-Marc Van Ravels. Retrieved 9 July 2022. – Red Star Line colour postcards

- "Red Star Line, Belgenland (2)". Simplon Postcards. Ian Boyle. – Red Star Line colour postcards

- "Red Star Liner "Belgenland"". Vintage Vacations. Blogger. 2 August 2008. – interior photos, passenger games on deck, materials from World cruise

- "SS Belgenland - History, Accommodations, & Ephemera Collection". Red Star Line – via GG Archives.

- "SS Belgenland". Cabin Liners. - Interior tour and photographs

- "Detailed Deck Plans for SS Belgenland". Ingebonden scheepsplannen van de 'R.M.S. "Belgenland" Red Star Line'.

- "RED STAR 'ROUND THE WORLD: S.S. BELGENLAND". Wanted on Voyage: Ocean Liner Monographs by Peter C Kohler. - extremely detailed history of the ship with numerous images