Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway

| Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway | |

|---|---|

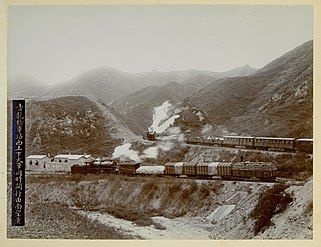

Two trains with Mallet locomotives passing the Qinglongqiao Station on the Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway | |

| Overview | |

| Status | Operational |

| Locale | |

| Termini | |

| Stations | Beijing North railway station Badaling railway station Shalingzi West railway station |

| Service | |

| Type | |

| System | National Rail |

| Operator(s) | |

| History | |

| Opened | 1909[1]: 12 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 201.2 kilometres (125.0 mi) |

| Number of tracks | Double track |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

The Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway or Jingzhang Railway (Chinese: 京张铁路; pinyin: Jīngzhāng Tiělù), also known as the Imperial Peking–Kalgan Railway, is China’s first railway that has been designed and built solely by Chinese, situated in the nation’s capital Beijing and Zhangjiakou City in Hebei Province. It was built in 1905–1909 under the proposal of Viceroy of Zhili Yuan Shikai and Assistant Director-General of Railways Hu Yufen (胡燏棻), with Zhan Tianyou as engineer-in-chief. When building the railway, Zhan reduced the length of Badaling Tunnel by using a switchback—or “人”-shaped rail track called in China as the shape of it resembles the Chinese character “人” (pinyin: rén; literally: people); he also used vertical shafts to facilitate the excavation of the tunnel.

The railway formally opened in 1909, with a total length of 201.2 km (125.0 mi). Starting from Liucun Village in Fengtai, it connected Beijing to Zhangjiakou via the Guan’gou Valley with 14 stations, 4 tunnels and 125 bridges. In 1912, four stations with passing loops were built in the Guan’gou section. The railway was merged into Beijing-Suiyuan Railway in 1916, and later into Beijing-Baotou Railway after the founding of People's Republic of China (PRC).

The rail tracks located within the city area of Beijing were gradually dismantled to meet the need of urban traffic. In 1995, the former Xizhimen Station was designated as a Major Historical and Cultural Site of Beijing, and in 2013, the section between Nankou and Badaling was listed as Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]In late 19th century, railway and mining became targets of Western powers in their colonial endeavours in China. In 1895, the Guangxu Emperor issued an imperial edict, claiming to carry out a national reform through a variety of measures, where railway construction was considered a top priority. Britain and Russia thus began competing for the power to build railways in North China, but the Qing government rejected both of them in 1898. Around a year later in 1899, Kinder, the British engineer-in-chief of the Imperial Railways of North China (关内外铁路), carried out preliminary surveying in areas between Beijing and Zhangjiakou, and this led to the rivalry between Britain and Russia for the control of Inner Mongolia. Russia made a request to the Qing government for approval of building the railway, but was refused by the latter.

On June 1, 1899, Russia forced the Qing government to make a commitment that it would consult Russia or Russian companies beforehand in the case that companies from any third country wanted to build railways in the north of Beijing or Northeast China.

After the Siege of the International Legations, the Qing government signed with Britain Regulations on Britain Returning the Imperial Railways of North China (《英国交还铁路章程》) and Regulations on Following the Returning of the Imperial Railways of North China (《关内外铁路交还以后章程》), which excluded any third country from building railways in areas within 80 miles in the north and south of the Shanhai Pass and between Fengtai and the Great Wall in the north. This caused objection of Russia and France, which made representations to the Qing government on the latter Regulations. Ultimately, it was agreed that no foreign capital shall be used to build railways in the north of Beijing, including the railway between Beijing and Zhangjiakou, and neither the railways, if built, nor the revenue made from the railways shall be transferred to foreign countries as collateral.[2]: 31-32

Planning

[edit]In 1905, Viceroy of Zhili Yuanshikai and Assistant Director-General of Railways Hu Yufen submitted a memorial to the throne, asking for approval to build the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway. The project was expected to take 4 years at a cost of 5 million taels of silver. The Imperial Railways of North China would contribute 1 million taels of silver annually to the budget and in return, receive 800,000 taels of silver per year from the Boxer Indemnities.[3]: 271 The proposal was approved in February the same year.[2]: 32-33;410

Based on the recommendation of Liang Dunyan (梁敦彦), Yuan Shikai chose Zhan Tianyou as the chief engineer.[4] In May the same year, the Qing government appointed Chen Zhaochang (陈昭常) as the director-general of the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway and Zhan Tianyou as the assistant director-general and chief engineer. Meanwhile, the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway Administration was established in Tianjin, and a branch office was opened in Fuchengmen, Beijing.[2]: 32-33;410 Zhan Tianyou soon led two Chinese graduates of railway engineering Xu Wenhui (徐文洄) and Zhang Honggao (张鸿诰) to carry out the surveying[5]: 205 They started in Liucun Village, and proceeded in Nankou, Guan’gou, and Badaling. On May 31, they reached Zhangjiakou and tried to find a site for the Zhangjiakou Station. Before deciding the final location of the station, Zhan visited Governor-General of Chahar Pu Ting (溥颋) and other local officials.[6]

Construction

[edit]Construction began on October 2, 1905,[7]: 17 in three sections.

This section was 55 km long, starting from Bridge 60 of Beijing-Fengtian Railway (京奉铁路) located in the east of Fengtai Station in Liucun (柳村). When building the section, the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway borrowed sites and facilities from the Imperial Railways of North China, and agreed, through negotiation, to pay the latte an annual rent of 200 taels of silver. On September 30, 1906, the section was fully built and put in use.[2]: 38 Meanwhile, the Xizhimen Station (西直门站), designed by the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway Administration, was established also in 1905–1906.[8]: 483

This section was 16.5 km long, covering the most challenging part in the Guan’gou Valley (关沟). To be closer to the construction site, Zhan Tianyou moved his office to Nankou.[2]: 38 In order to satisfy the need for ballast and locomotives, a ballast factory was built in Nankou in 1906,[a][9]: 357 and a locomotive factory, the Jingzhang Manufactory (京张制造厂), was established in the same year.[b][8]: 372 When building the railway going through the Jundu Mountain, Zhan Tianyou used a zigzag,[c] at a high gradient of 0.033. Owed to the design, the length of the Badaling Tunnel was reduced from 1.8 km, which was beyond the construction capacity back then, to 1.095 km.[5]: 205-206 [2]: 241 Before the excavation in Badaling began, Japanese merchant Amemiya Keijirou (雨宫敬次郎) and Kinder recommended foreign machinery and contractors to Zhan Tianyou as a solution to the seemingly unconquerable task. Zhan, however, stood fast on using an all-Chinese team. When building the tunnel, in addition to cutting from the two sides of the mountain, Zhan also drilled two vertical shafts from the mountaintop, so that workers can excavate within the mountain on four surfaces simultaneously. Of the two shafts, the bigger one was 33 m deep and 3.05 m wide. Together, they contributed to a daily excavation of 0.9 m. Also, with fans installed, the shafts could bring air to the tunnel, and served, after the tunnel was finished, as ventilation shafts, through which the smoke puffed by the train could run out. To accelerate the construction, workers worked in shifts. Among the 60 people in each shift, 40 were responsible for blasting and 20 for transportation.[2]: 38-39 When building the rail track going through the Juyong Pass, Zhan decided to build a tunnel in the nearby mountain to avoid damaging civilian houses.[10] During the excavation, the construction team found a gorge that had probably been blocked by other people, which, together with the soft mountain rocks and soil, posed a great challenge to the construction.[2]: 39-40 In 1907, the Qing government ordered the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway Administration to plant trees along the railway.[11]: 149 On April 14, 1908, the 367 m Juyongguan Tunnel was completed, and on May 22, the 1,090.5 m Badaling Tunnel was completed. Before that, construction work of the 141 m and 46 m tunnels in Shifosi (石佛寺) and Wuguitou (五桂头) had been finished.[2]: 39-40

Section III: Chadaocheng-Huailai-Zhangjiakou

[edit]The section was 129.7 km long. The construction started even before the second section was completed, and work on this section was largely accelerated by the completion of the first two sections as construction materials could be transported by rail. The major challenges in this section lied in the Huailai River Bridge (怀来河大桥) and the section between Jiming Mountain (鸡鸣山) and Xiangshuipu (响水铺). For the former, Zhan Tianyou built a steel truss bridge with timber-pile foundation and concrete abutments; for the latter, the riverbed was raised with fillings, and cement was used to protect the track from flood damage. On July 4, the railway finally reached Zhangjiakou.[2]: 39-40

Opening

[edit]

On August 11, 1909, with some final work finished, the project was formally completed. On September 19, Minister of Posts and Communications Xu Shichang, Director-General of Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway Zhan Tianyou, and Assistant Director-General of Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway Guan Mianjun (关冕钧) took the train and checked the railway section by section. A celebration tea party was held in Zhangjiakou on September 21. On September 24, the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway was formally opened. An opening ceremony was held in the Nankou Station on October 2,[1]: 12;894 with over 10,000 people present, including foreign diplomats in Beijing and Tianjin, representatives of the minister of Beiyang (北洋大臣), and senior officials of the Ministry of Post and Communications. Xu Shichang, Zhan Tianyou, and Zhu Junqi (朱君淇) made speeches on the ceremony.[2]: 40-43 The actual total cost of the 201.2 km (125.0 mi) railway was 289,000 less than the initially expected 7.29 million taels of silver, and the cost per km (34,500 taels of silver) marked the lowest of all railways in China. More importantly, the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway was Qing Dynasty’s first and only railway that had been designed, built, and managed solely by Chinese.[2]: 40;423

The North British Locomotive Company delivered three Mallet locomotives for the railway. They were the first ever built articulated compound locomotives in Great Britain and were designed to work on steep 1:30 grades and 500 ft radius curves of the route. Only the locomotives were built in Great Britain, the tenders were localy supplied.[12]

After the opening, the railway was used for various purposes, including transporting mails between Fengtai and Zhangjiakou.[13]: 211 The Qinghe railway station gradually took place of the Qinghe waterway in transporting passengers and cargo.[7]: 659 [14]: 847 The ballast production in Nankou ended, while the Jingzhang Manufactory expanded.[8]: 372

Later development

[edit]

In 1910, the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway Engineering Bureau moved to Zhangjiakou under the new name of Zhangjiakou-Suiyuan Railway Engineering Bureau, to support the construction of Zhangjiakou-Suiyuan Railway (张绥铁路). In September 1912, Sun Yat-sen (孙中山), who resigned from the post of interim president of Republic of China, showed great interest in railway undertaking. He met Yuan Shikai in Beijing, and took an inspection tour to Zhangjiakou by train. In 1916, as the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway Authority merged into the Beijing-Suiyuan Railway Authority, the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway became a part of the Beijing-Suiyuan Railway. In April 1921, the railway extended westward to Suiyuan, and further to Baotou in January 1923. In 1928, the Beijing-Suiyuan Railway was renamed Peking-Suiyuan Railway (平绥铁路), and was renamed again after the establishment of PRC as Beijing-Baotou Railway.[2]: 10;44-45;399 In 1924, six kilometres of the railway near the Xiahuayuan Station (下花园站) was relocated due to flood damage. After the outbreak of Japanese Aggression against China, the railway was seized by Japanese army. On July 25, 1939, ten kilometres of the railway in the Huailai section was relocated due to flood damage, and the Wuguitou Tunnel and Shifosi Tunnel were discarded also because of flood damage. In 1940, four newly built tunnels and five newly built bridges were put in use, and the ruling gradient rose from 0.333 to 0.358.[2]: 10;44-45 In 1953, the railway between Kangzhuang (康庄) and Langshan (狼山) was relocated.[2]: 44-47 In 1960, due to the expansion of Tsinghua University, the rail track in the north of Qinghuayuan Station was relocated to the east, and new buildings were established in the south of the original station, which turned into a freight yard.[7]: 658 In 1968, due to the need of Beijing's urban traffic, the railway between Guang’anmen and Xizhimen was dismantled, while that between Liucun and Guang’anmen maintained operation.[2]: 48 In 2016, for the construction of Beijing-Zhangjiakou inter-city railway, rail tracks within the Beijing city were all dismantled and the Qinghuayuan Station was closed permanently.[15]

Commemoration and conservation

[edit]In 1919, Zhan Tianyou died of disease in Hankou at age of 58. In commemoration of him, in 1922, the Chinese Engineers Society (中国工程师学会), together with the Association of Colleagues of Beijing-Suiyuan Railway (京绥铁路同人会) and other organisations, built a 3 m high bronze statue of him in the Qinglongqiao Station. In 1926, Zhan's wife Tan Juzhen died and was buried with him. In 1982, the Ministry of Railways of PRC, the Beijing Railway Administration, and the China Railway Society moved their tomb in Baiwanzhaung (百万庄) in west Beijing to a new burial ground behind the bronze statue in the Qinglongqiao Station.[16]: 514 In 1995, the former Xizhimen Station was listed as Major Historical and Cultural Site of Beijing under the name of “Former Xizhimen Station of Peking-Suiyuan Railway”.[17]: 715 In 2007, an industrial historical site survey team, organised by the Capital Museum and Beijing Daily, discovered along the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway over 100 historical sites.[18] In 2009, in the third national archaeological survey, the Zhangjiakou Station, Xinbaoan Station and other former stations were listed as industrial historical sites.[19] In the same year, the Capital Museum and cultural heritage committees of districts and counties along the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway made a joint application for listing the whole railway as national cultural heritage.[20] In 2013, the section from Nankou to Badaling was designated as Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level, with historical sites including buildings of the Nankou Station, remains of Nankou locomotive manufactory, the switchback, station buildings, staff accommodation and supervision office of the Qinglongqiao Station, and Zhan Tianyou's tomb and bronze statue.[21][22] In 2016, reservation plans were drafted for remains of the Beijing–Zhangjiakou Railway that have been listed as Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level and included in the third national cultural heritage survey.[23]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b 段育达主编; 北京市西城区志编纂委员会编, eds. (1 August 1999). Beijing Shi Xicheng Qu zhi. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 979. ISBN 7-200-03779-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p 北京市地方志编纂委员会 (2003). Beijing Municipal Research railway Chi Chi. 北京: 北京出版社. ISBN 7-200-05098-9.

- ^ 北京市地方志编纂委员会编著, ed. (1 November 2000). Beijing Zhi Chi Comprehensive Economic Management Financial Analysis. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 716. ISBN 7-200-04179-3.

- ^ 汤礼春 (July 1999). "文史精华": 35–36.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b 北京市地方志编纂委员会编著, ed. (1 December 2001). Chi Chi Beijing Surveying and Mapping. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 610. ISBN 7-200-04400-8.

- ^ 邵新春 (June 2002). "北京档案": 30–31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c 北京市海淀区地方志编纂委员会编 (1 April 2004). Haidian District, Beijing, Chi. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 1063. ISBN 7-200-05091-1.

- ^ a b c d 张明义等主编; 北京市地方志编纂委员会编; 李燕秋卷主编, eds. (1 September 2003). Architecture, Beijing Architecture Research Notes. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 1014. ISBN 7-200-04939-5.

- ^ a b 北京市地方志编纂委员会编著, ed. (1 September 2001). Beijing Zhi Chi power industry building materials industry blog. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 610. ISBN 7-200-04359-1.

- ^ a b 吕世微 (January 1984). "历史教学": 34–35.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ 张明义等主编; 北京市地方志编纂委员会编, eds. (1 February 2003). Beijing Forestry Chi Chi. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 612. ISBN 7-200-04671-X.

- ^ Gairns, J.F. (1909). "Some remarkable locomotives of 1908". Cassier's Magazine. 36: 105–106.

- ^ 北京市地方志编纂委员会 (1 March 2004). Beijing Municipal Research Post Chi Chi. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 416. ISBN 7-200-05002-4.

- ^ 通州区地方志编纂委员会编, ed. (1 November 2003). Tong County. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 930. ISBN 7-200-05086-5.

- ^ "清华园站关闭 "五道口"将拆除" [Tsinghua Park Station closed, "Wudaokou" will be demolished]. 新京报. 2 November 2016.

- ^ 北京市地方志编纂委员会 (1 April 2003). Volume Home Administration Blog Beijing Blog. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 656. ISBN 7-200-04941-7.

- ^ 张明义; 王立行; 段柄仁主编; 宋惕冰(卷)主编; 北京市地方志编纂委员会编, eds. (1 March 2006). Beijing zhi. 北京: 北京出版社. p. 784. ISBN 7-200-05631-6.

- ^ "京张铁路发现百余处文物遗址 1898年老铁轨面世" [More than 100 cultural relics found on the Beijing-Zhangjiang Railway]. 中国网. 26 October 2007.

- ^ 尹洁; 陈玉杰; 刘萍 (4 September 2009). 河北日报: 7.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "京张铁路拟整体申报文保单位" [Beijing-Zhanghai Railway intends to declare the overall cultural protection unit]. 新京报. 24 August 2009.

- ^ "北京28处古迹"晋升"全国文保单位" [28 historical sites in Beijing "promoted" national cultural protection units]. 新京报. 5 June 2013.

- ^ "京张铁路 老建筑现拆字引虚惊(组图)" [Beijing-Zhanghai Railway, old buildings are now demolished to cause false alarm (Photos)]. 法制晚报(北京). 7 December 2015. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017.

- ^ "京张铁路部分地段正编制保护规划" [Some sections of Beijing-Zhanghai Railway are preparing protection plans]. 法制晚报(北京). 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016.