Vinland

| Part of a series on the |

| Norse colonization of North America |

|---|

|

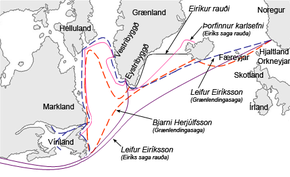

Vinland, Vineland,[2][3] or Winland[4] (Old Norse: Vínland hit góða, lit. 'Vinland the Good') was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Eriksson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot.[5] The name appears in the Vinland Sagas, and describes Newfoundland and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence as far as northeastern New Brunswick. Much of the geographical content of the sagas corresponds to present-day knowledge of transatlantic travel and North America.[6]

In 1960, archaeological evidence of the only known Norse site in North America,[7][8] L'Anse aux Meadows, was found on the northern tip of the island of Newfoundland. Before the discovery of archaeological evidence, Vinland was known only from the sagas and medieval historiography. The 1960 discovery further proved the pre-Columbian Norse exploration of mainland North America.[7] L'Anse aux Meadows has been hypothesized to be the camp Straumfjörð mentioned in the Saga of Erik the Red.[9][10]

Name

[edit]Vinland was the name given to part of North America by the Icelandic Norseman Leif Eriksson, about 1000 AD. It was also spelled Winland,[4] as early as Adam of Bremen's Descriptio insularum Aquilonis ("Description of the Northern Islands", ch. 39, in the 4th part of Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum), written circa 1075. Adam's main source regarding Winland appears to have been king Svend Estridson, who had knowledge of the "northern islands". The etymology of the Old Norse root vin- is disputed; while it has usually been assumed to be "wine", some scholars give credence to the homophone vin, meaning "pasture" or "meadow". Adam of Bremen implies that the name contains Old Norse vín (cognate with Latin vinum) "wine" (rendered as Old Saxon or Old High German wīn): "Moreover, he has also reported one island discovered by many in that ocean, which is called Winland, for the reason that grapevines grow there by themselves, producing the best wine."[11] This etymology is retained in the 13th-century Grœnlendinga saga, which provides a circumstantial account of the discovery of Vinland and its being named from the vínber, i.e. "wineberry", a term for grapes or currants (black or red), found there.[12]

There is also a long-standing Scandinavian tradition of fermenting berries into wine. The discovery of butternuts at the site implies that the Norse explored Vinland further to the south, at least as far as St. Lawrence River and parts of New Brunswick, the northern limit for both butternut and wild grapes (Vitis riparia).[9][10]

Another proposal for the name's etymology, was introduced by Sven Söderberg in 1898 (first published in 1910).[13] This suggestion involves interpreting the Old Norse name not as vín-land with the first vowel spoken as /iː/, but as vin-land, spoken as /ɪ/; a short vowel. Old Norse vin (from Proto-Norse winju) has a meaning of "meadow, pasture".[14] This interpretation of Vinland as "pasture-land" rather than "wine-land" was accepted by Valter Jansson in his classic 1951 dissertation on the vin-names of Scandinavia, by way of which it entered popular knowledge in the later 20th century. It was rejected by Einar Haugen (1977), who argued that the vin element had changed its meaning from "pasture" to "farm" long before the Old Norse period. Names in vin were given in the Proto Norse period, and they are absent from places colonized in the Viking Age.[15]

Kirsten A. Seaver also rejects the "Pastureland" interpretation of the name 'Vínland'. On page 24 of "The Frozen Echo[16]" 1996, she writes, "The notion that the first syllable was vin with a short vowel (meaning ”green meadow”) has been so thoroughly discarded that we are left with the incontrovertible, long-vowelled vín or “wine”

There is a runestone which may have contained a record of the Old Norse name slightly predating Adam of Bremen's Winland. The Hønen Runestone was discovered in Norderhov, Norway, shortly before 1817, but it was subsequently lost. Its assessment depends on a sketch made by antiquarian L. D. Klüwer (1823), now also lost but in turn copied by Wilhelm Frimann Koren Christie (1838). The Younger Futhark inscription was dated to c. 1010–1050. The stone had been erected in memory of a Norwegian, possibly a descendant of Sigurd Syr. Sophus Bugge (1902) read part of the inscription as:

ᚢᛁᚿ᛫(ᛚ)ᛆ(ᛐ)ᛁᚭ᛫ᛁᛌᛆ

uin (l)a(t)ią isa

Vínlandi á ísa

"from Vinland over ice".

This is highly uncertain; the same sequence is read by Magnus Olsen (1951) as:

ᚢᛁᚿ᛫ᚴᛆ(ᛚᛐ)ᚭ᛫ᛁᛌᛆ

uin ka(lt)ą isa

vindkalda á ísa

"over the wind-cold ice".[17]

The Vinland Sagas

[edit]

The main sources of information about the Norse voyages to Vinland are two Icelandic Sagas: the Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders, which are known collectively as the Vinland Sagas. These stories were preserved by oral tradition until they were written down some 250 years after the events they describe. The existence of two versions of the story shows some of the challenges of using traditional sources for history, because they share a large number of story elements but use them in different ways. A possible example is the reference to two different men named Bjarni who are blown off course. A brief summary of the plots of the two sagas, given at the end of this article, shows other examples.

The sagas report that a considerable number of Vikings were in parties that visited Vinland. Thorfinn Karlsefni's crew consisted of 140 or 160 people according to the Saga of Erik the Red, 60 according to the Saga of the Greenlanders. Still according to the latter, Leif Ericson led a company of 35, Thorvald Eiriksson a company of 30, and Helgi and Finnbogi had 30 crew members.[18]

According to the Saga of Erik the Red, Þorfinnr "Karlsefni" Þórðarson and a company of 160 men, going south from Greenland traversed an open stretch of sea, found Helluland, another stretch of sea, Markland, another stretch of sea, the headland of Kjalarnes, the Wonderstrands, Straumfjörð and at last a place called Hóp, a bountiful place where no snow fell during winter. However, after several years away from Greenland, they chose to turn back to their homes when they realized that they would otherwise face an indefinite conflict with the natives.

This saga references the place-name Vinland in four ways. First, it is identified as the land found by Leif Erikson. Karlsefni and his men subsequently find "vín-ber" near the Wonderstrands. Later, the tale locates Vinland to the south of Markland, with the headland of Kjalarnes at its northern extreme. However, it also mentions that while at Straumfjord, some of the explorers wished to go in search for Vinland west of Kjalarnes.

Saga of the Greenlanders

[edit]

In Grænlendinga saga or the 'Saga of the Greenlanders', Bjarni Herjólfsson accidentally discovered the new land when traveling from Norway to visit his father, in the second year of Erik the Red's Greenland settlement (about 986 CE). When he managed to reach Greenland, making land at Herjolfsness, the site of his father's farm, he remained there for the rest of his father's life and didn't return to Norway until about 1000 CE. There, he told his overlord (the Earl, also named Erik) about the new land and was criticized for his long delay in reporting this. On his return to Greenland he retold the story and inspired Leif Eriksson to organize an expedition, which retraced in reverse the route Bjarni had followed, past a land of flat stones (Helluland) and a land of forests (Markland). After having sailed another two days across open sea, the expedition found a headland with an island just off the shore, with a nearby pool, accessible to ships at high tide, in an area where the sea was shallow with sandbanks. Here the explorers landed and established a base which can plausibly be matched to L'Anse aux Meadows; except that the winter was described as mild, not freezing. One day an old family servant, Tyrker, went missing and was found mumbling to himself. He eventually explained that he found grapes/currants. In the spring, Leif returned to Greenland with a shipload of timber, towing a boatload of grapes/currants. On the way home, he spotted another ship aground on the rocks, rescued the crew and later salvaged the cargo. A second expedition, one ship of about 40 men led by Leif's brother Thorvald, sets out in the autumn after Leif's return and stayed over three winters at the new base (Leifsbúðir (-budir), meaning Leif's temporary shelters), exploring the west coast of the new land during the first summer, and the east coast during the second, running aground and losing the ship's keel on a headland they christen Keel Point (Kjalarnes). Further south, at a point where Thorvald wanted to establish a settlement, the Greenlanders encountered some of the local inhabitants (Skrælingjar) and killed them, following which they were attacked by a large force in hide boats, and Thorvald died from an arrow-wound. After the exploration party returned to base, the Greenlanders decided to return home the following spring.

Thorstein, Leif's brother, married Gudrid, widow of the captain rescued by Leif, then led a third expedition to bring home Thorvald's body, but drifted off course and spent the whole summer sailing the Atlantic. Spending the winter as a guest at a farm on Greenland with Gudrid, Thorstein died of disease, reviving just long enough to make a prophecy about her future as a Christian. The next winter, Gudrid married a visiting Icelander named Thorfinn Karlsefni, who agreed to undertake a major expedition to Vinland, taking livestock. On arrival, they soon found a beached whale which sustained them until spring. In the summer, they were visited by some of the local inhabitants who were scared by the Greenlanders' bull, but happy to trade goods for milk and other products. In autumn, Gudrid gave birth to a son, Snorri. Shortly after this, one of the local people tried to take a weapon and was killed. The explorers were then attacked in force, but managed to survive with only minor casualties by retreating to a well-chosen defensive position, a short distance from their base. One of the local people picked up an iron axe, tried it, and threw it away.

The explorers returned to Greenland in summer with a cargo of grapes/currants and hides. Shortly thereafter, a ship captained by two Icelanders arrived in Greenland, and Freydis, daughter of Eric the Red, persuaded them to join her in an expedition to Vinland. When they arrived at Vinland, the brothers stored their belongings in Leif Eriksson's houses, which angered Freydis and she banished them. She then visited them during the winter and asked for their ship, claiming that she wanted to go back to Greenland, which the brothers happily agreed to. Freydis went back and told her husband the exact opposite, which led to the killing, at Freydis' order, of all the Icelanders, including five women, as they lay sleeping. In the spring, the Greenlanders returned home with a good cargo, but Leif found out the truth about the Icelanders. That was the last Vinland expedition recorded in the saga.

Saga of Erik the Red

[edit]

In the other version of the story, Eiríks saga rauða or the Saga of Erik the Red, Leif Ericsson accidentally discovered the new land when traveling from Norway back to Greenland after a visit to his overlord, King Olaf Tryggvason, who commissioned him to spread Christianity in the colony. Returning to Greenland with samples of grapes/currants, wheat and timber, he rescued the survivors from a wrecked ship and gained a reputation for good luck; his religious mission was a swift success. The next spring, Thorstein, Leif's brother, lead an expedition to the new land, but drifted off course and spent the whole summer sailing the Atlantic. On his return, he met and married Gudrid, one of the survivors from a ship which made land at Herjolfsnes after a difficult voyage from Iceland. Spending the winter as a guest at a farm on Greenland with Gudrid, Thorstein died of disease, reviving just long enough to make a prophecy about her future as a far-traveling Christian. The next winter, Gudrid married a visiting Icelander named Thorfinn Karlsefni, who, with his business partner Snorri Thorbrandsson, agreed to undertake a major expedition to the new land, taking livestock with them. Also contributing ships for this expedition were another pair of visiting Icelanders, Bjarni Grimolfsson and Thorhall Gamlason, and Leif's brother and sister Thorvald and Freydis, with her husband Thorvard. Sailing past landscapes of flat stones (Helluland) and forests (Markland) they rounded a cape where they saw the keel of a boat (Kjalarnes), then continued past some extraordinarily long beaches (Furðustrandir) before they landed and sent out two runners to explore inland. After three days, the pair returned with samples of grapes/currants and wheat. After they sailed a little farther, the expedition landed at an inlet next to an area of strong currents (Straumfjörð), with an island just off shore (Straumsey), and they made camp. The winter months were harsh, and food was in short supply. One day an old family servant, Thorhall the Hunter (who had not become Christian), went missing and was found mumbling to himself. Shortly afterwards, a beached whale was found, which Thorhall claimed had been provided in answer to his praise of the pagan gods. The explorers found that eating it made them ill, so they prayed to the Christian God, and shortly afterwards the weather improved.

When spring arrived, Thorhall Gamlason, the Icelander, wanted to sail north around Kjalarnes to seek Vinland, while Thorfinn Karlsefni preferred to sail southward down the east coast. Thorhall took only nine men, and his vessel is swept out into the ocean by contrary winds; he and his crew never returned. Thorfinn and Snorri, with Freydis (plus possibly Bjarni), sailed down the east coast with 40 men or more and established a settlement on the shore of a seaside lake, protected by barrier islands and connected to the open ocean by a river which was navigable by ships only at high tide. The settlement was known as Hóp, and the land abounded with grapes/currants and wheat. The teller of this saga was uncertain whether the explorers remained here over the next winter (said to be very mild) or for only a few weeks of summer. One morning they saw nine hide boats; the local people (Skrælings) examined the Norse ships and departed in peace. Later a much larger flotilla of boats arrived, and trade commenced (Karlsefni forbade the sale of weapons). One day, the local traders were frightened by the sudden arrival of the Greenlanders' bull, and they stayed away for three weeks. They then attacked in force, but the explorers managed to survive with only minor casualties, by retreating inland to a defensive position, a short distance from their camp. Pregnancy slowed Freydis down, so she picked up the sword of a fallen companion and brandished it against her bare breast, scaring the attackers into withdrawal. One of the local people picked up an iron axe, tried using it, but threw it away. The explorers subsequently abandoned the southern camp and sailed back to Straumsfjord, killing five natives they encountered on the way, lying asleep in hide sacks.

Karlsefni, accompanied by Thorvald Eriksson and others, sailed around Kjalarnes and then south, keeping land on their left side, hoping to find Thorhall. After sailing for a long time, while moored on the south side of a west-flowing river, they were shot at by a one-footed man, and Thorvald died from an arrow-wound. Once they reached Markland, the men encountered five natives, of whom they kidnapped two boys, baptizing them and teaching them their own language.[20] The explorers returned to Straumsfjord, but disagreements during the following winter led to the abandonment of the venture. On the way home, the ship of Bjarni the Icelander was swept into the Sea of Worms (Maðkasjár in Skálholtsbók, Maðksjár in Hauksbók) by contrary winds. The marine worms destroyed the hull, and only those who escaped in the ship's worm-proofed boat survived. This was the last Vinland expedition recorded in the saga.[21]

Medieval geographers

[edit]Adam of Bremen

[edit]The oldest commonly acknowledged surviving written record of Vinland appears in Descriptio insularum Aquilonis by Adam of Bremen written in about 1075. Adam was told about "islands" discovered by Norse sailors in the Atlantic by the Danish king Svend Estridsen.[22]

Galvano Fiamma

[edit]The nearby Norse outpost of Markland was mentioned in the writings of Galvano Fiamma in his book, Cronica universalis. He is believed to be the first Southern European to write about the New World.[23]

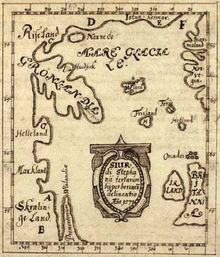

Sigurd Stefansson

[edit]The earliest map of Vinland was drawn by Sigurd Stefansson, a schoolmaster at Skalholt, Iceland, around 1570, which placed Vinland somewhere that can be Chesapeake Bay, St. Lawrence, or Cape Cod Bay.[24]

In the early 14th Century, a geography encyclopedia called Geographica Universalis was compiled at Malmesbury Abbey in England, which was in turn used as a source for one of the most widely circulated medieval English educational works, Polychronicon by Ranulf Higden, a few years later. Both these works, with Adam of Bremen as a possible source, were confused about the location of what they called Wintland—the Malmesbury monk had it on the ocean east of Norway, while Higden put it west of Denmark but failed to explain the distance. Copies of Polychronicon commonly included a world map on which Wintland was marked in the Atlantic Ocean near Iceland, but again much closer to the Scandinavian mainland than in reality. The name was explained in both texts as referring to the savage inhabitants' ability to tie the wind up in knotted cords, which they sold to sailors who could then undo a knot whenever they needed a good wind. Neither mentioned grapes, and the Malmesbury work specifically states that little grows there but grass and trees, which reflects the saga descriptions of the area round the main Norse expedition base.[25]

More geographically correct were Icelandic texts from about the same time, which presented a clear picture of the northern countries as experienced by Norse explorers: north of Iceland a vast, barren plain (which we now know to be the Polar ice-cap) extended from Biarmeland (northern Russia) east of the White Sea, to Greenland, then further west and south were, in succession, Helluland, Markland and Vinland. The Icelanders had no knowledge of how far south Vinland extended, and they speculated that it might reach as far as Africa.[26]

The "Historia Norwegiae" (History of Norway), compiled around 15th–16th century, does not refer directly to Vinland and tries to reconcile information from Greenland with mainland European sources; in this text Greenland's territory extends so that it is "almost touching the African islands, where the waters of ocean flood in".[27]

Later Norse voyages

[edit]Icelandic chronicles record another attempt to visit Vinland from Greenland, over a century after the saga voyages. In 1121, Icelandic bishop Eric Gnupsson, who had been based on Greenland since 1112, "went to seek Vinland". Nothing more is reported of him, and three years later another bishop, Arnald, was sent to Greenland. No written records, other than inscribed stones, have survived in Greenland, so the next reference to a voyage also comes from Icelandic chronicles. In 1347, a ship arrived in Iceland, after being blown off course on its way home from Markland to Greenland with a load of timber. The implication is that the Greenlanders had continued to use Markland as a source of timber over several centuries.[28]

Controversy over the location of Vinland

[edit]

The definition of Vinland is somewhat elusive. According to a 1969 article by Douglas McManis in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers,[29]

The study of the early Norse voyages to North America is a field of research characterized by controversy and conflicting, often irreconcilable, opinions and conclusions. These circumstances result from the fact that details of the voyages exist only in two Icelandic sagas which contradict each other on basic issues and internally are vague and contain nonhistorical passages.

This leads him to conclude that "there is not a Vinland, there are many Vinlands". According to a 1970 reply by Matti Kaups in the same journal,[30]

Certainly there is a symbolic Vinland as described and located in the Groenlandinga saga; what seems to be a variant of this Vinland is narrated in Erik the Red's Saga. There are, on the other hand, numerous more recent derivative Vinlands, each of which actually is but a suppositional spatial entity. (...) (e.g. Rafn's Vinland, Steensby's Vinland, Ingstad's Vinland, and so forth).

In geographical terms, Vinland is sometimes used to refer generally to all areas in Atlantic Canada. In the sagas, Vinland is sometimes indicated to not include the territories of Helluland and Markland, which appear to also be located in North America beyond Greenland. Moreover, some sagas establish vague links between Vinland and an island or territory that some sources refer to as Hvítramannaland.[31]

Another possibility is to interpret the name of Vinland as not referring to one defined location, but to every location where vínber could be found, i.e. to understand it as a common noun, vinland, rather than a toponym, Vinland. The Old Norse and Icelandic languages were, and are, very flexible in forming compound words.

Sixteenth century Icelanders realized that the "New World" which European geographers were calling "America" was the land described in their Vinland Sagas. The Skálholt Map, drawn in 1570 or 1590 but surviving only through later copies, shows Promontorium Winlandiae ("promontory/cape/foreland of Vinland") as a narrow cape with its northern tip at the same latitude as southern Ireland. (The scales of degrees in the map margins are inaccurate.) This effective identification of northern Newfoundland with the northern tip of Vinland was taken up by later Scandinavian scholars such as bishop Hans Resen.

Although it is generally agreed, based on the saga descriptions, that Helluland includes Baffin Island, and Markland represents at least the southern part of the modern Labrador, there has been considerable controversy over the location of the actual Norse landings and settlement. Comparison of the sagas, as summarized below, shows that they give similar descriptions and names to different places. One of the few reasonably consistent pieces of information is that exploration voyages from the main base sailed down both the east and west coasts of the land; this was one of the factors which helped archaeologists locate the site at L'Anse aux Meadows, at the tip of Newfoundland's long northern peninsula.

Erik Wahlgren examines the question in his book The Vikings and America, and points out clearly that L'Anse aux Meadows cannot be the location of Vínland, as the location described in the sagas has both salmon in the rivers and the 'vínber' (meaning specifically 'grape', that according to Wahlgren the explorers were familiar with and would have thus recognized), growing freely. Charting the overlap of the limits of wild vine and wild salmon habitats, as well as nautical clues from the sagas, Wahlgren indicates a location in Maine or New Brunswick. He hazards a guess that Leif Erikson camped at Passamaquoddy Bay and Thorvald Erikson was killed in the Bay of Fundy.[32]

On the other hand, Sir Wilfred Grenfell, a medical missionary and scholar living in Newfoundland and Labrador in the early 20th century wrote of the issue of the location of Vinland that,[33]

No reason has ever been shown why the Vikings would want to fare any farther than our beautifully wooded bays, with their endless berries, salmon, furs, and game, except that most people think of the east coast of Labrador as all barren, forbidding wastes, and forget that no part of it lies north of England and Scotland.

— The Romance of Labrador, "The Pageant of the Vikings", page 61

Other clues appear to place the main settlement farther south, such as the mention of a winter with no snow and the reports in both sagas of grapes being found. A very specific indication in the Greenlanders' Saga of the latitude of the base has also been subject to misinterpretation. This passage states that in the shortest days of midwinter, the sun was still above the horizon at "dagmal" and "eykt", two specific times in the Norse day. Carl Christian Rafn, in the first detailed study of the Norse exploration of the New World, "Antiquitates Americanae" (1837), interpreted these times as equivalent to 7:30 a.m. and 4:30 p.m., which would put the base a long way south of Newfoundland. According to the 1880 Sephton translation of the saga, Rafn and other Danish scholars placed Kjalarnes at Cape Cod, Straumfjörð at Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, and Straumsey at Martha's Vineyard.[34]

An Icelandic law text gives a very specific explanation of "eykt", with reference to Norse navigation techniques. The eight major divisions of the compass were subdivided into three hours each, to make a total of 24, and "eykt" was the end of the second hour of the south-west division. In modern terms this would be 3:30 p.m. "Dagmal", the "day-meal," is specifically distinguished from the earlier "rismal" (breakfast), and would thus be about 8:30 a.m.[35] The sun is indeed just above the horizon at these times on the shortest days of the year in northern Newfoundland - but not much farther north.

A 2012 article by Jónas Kristjánsson in the scientific journal Acta Archeologica, which assumes that the headland of Kjalarnes referred to in the Saga of Erik the Red is at L'Anse aux Meadows, suggests that Straumfjörð refers to Sop's Arm, Newfoundland, as no other fjord in Newfoundland was found to have an island at its mouth.[19] Kent Budden (1962-2008) a resident of Sop's Arm, did extensive exploration in the area, contacted Jonas to show him some artifacts, including an axe head that Jonas said had a twin in the Icelandic Museum. Kent believed he had confirmed Kristjansson's theory.

L'Anse aux Meadows

[edit]

Newfoundland marine insurance agent and historian William A. Munn (1864–1939), after studying literary sources in Europe, suggested in his 1914 book Location of Helluland, Markland & Vinland from the Icelandic Sagas that the Vinland explorers "went ashore at Lancey [sic] Meadows, as it is called to-day".[36] In 1960, the remains of a small Norse encampment[7] were discovered by Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad at that exact spot, L'Anse aux Meadows in northern Newfoundland, and excavated during the 1960s and 1970s. It is most likely this was the main settlement of the sagas, a "gateway" for the Norse Greenlanders to the rich lands farther south. Many wooden objects were found at L'Anse aux Meadows, and radiocarbon dating confirms the site's occupation as being confined to a short period around 1000 CE. In addition, small pieces of jasper, known to have been used in the Norse world as fire-strikers, were found in and around the different buildings. When these were analyzed and compared with samples from jasper sources around the North Atlantic area, it was found that two buildings contained only Icelandic jasper pieces, while another contained some from Greenland; a single piece from the east coast of Newfoundland was found. These finds appear to confirm the saga claim that some Vinland exploration ships came from Iceland and that they ventured down the east coast of the new land.[37] In 2021, wood from the site was shown to have been cut in 1021, using metal blades, which the local indigenous people did not have.[38]

Although it is now generally accepted that L'Anse aux Meadows was the main base of the Norse explorers,[39] the southernmost limit of Norse exploration remains a subject of intense speculation. Gustav Storm (1887) and Joseph Fischer (1902) both suggested Cape Breton; Samuel Eliot Morison (1971) the southern part of Newfoundland; Erik Wahlgren (1986) Miramichi Bay in New Brunswick; and Icelandic climate specialist Pall Bergthorsson (1997) proposed New York City.[40] The insistence in all the main historical sources that grapes were found in Vinland suggests that the explorers ventured at least to the south side of the St. Lawrence River, as Jacques Cartier did 500 years later, finding both wild vines and nut trees.[41] Three butternuts were found at L'Anse aux Meadows, another species which grows only as far north as the St. Lawrence.[9][42]

The vinviðir (wine wood) the Norse were cutting down in the sagas may refer to the vines of Vitis riparia, a species of wild grape that grows on trees. As the Norse were searching for lumber, a material that was needed in Greenland, they found trees covered with Vitis riparia south of L'Anse aux Meadows and called them vinviðir.[10]

L'Anse Aux Meadows was a small and short-lived encampment;[7] perhaps it was primarily used for timber-gathering forays and boat repair, rather than permanent settlements like Greenland.[43]

Vinland in Colonial Discourses

[edit]Sverrir Jakobsson notes that there are no contemporary written records of journeys to Vinland - pointing out that the earliest mentions of the location occured in 1070 and 1120.[44] Jakobsson points out that there are contradictions between Eiriks saga rautha and the Graenlandinga saga and that their textual history suggests they were composed independently of each other and he is highly crtical of treating the sagas as a cohesive unit. He also suggests that attempts at "harmonizing the evidence of the sagas with the modern belief that journeys were directed towards North America" has led to gaps in the scholarship surrounding the sagas. He notes references to Vinland in Icelandic manuscripts from around 1300 indicated Vinland as being in Africa. He treats this as being the influence of the medieval Catholic epistemology which only supported the existence of three continents. Based on this textual interpretation Jakobsson considers that the Norse travels to Vinland failed to discover America as they did not bring about the paradigmatic shift in Christian geography of later voyages to the New World.

According to Christopher Crocker, the search for Vinland is appropriately contextualized as a form of colonial construction of history. He suggests that centering Norse expeditions to North America play into the Vanishing Indian trope and allow for the continued centering of European historical narratives farther back into the history of North America, at the expense of Indigenous people. He points out that the claims of Beothuck extinction which the Vinland narrative supported were used by British setlers to deny Mi'kmaq land claims.[45] Anette Kolodny suggests that attempts to situate Vinland in New England "owed much to the fact that, by 1850 and the decades beyond, New England was in decline, and this effort reflected the attempt to recapture glory for the region.[46] Kolodny says that Wayne Newell, a Passamaquoddy elder said that the noisemakers referenced in the sagas were similar to traditional Wabanaki noisemakers he'd constructed as a child but that he could recall "no stories that clearly related to any arrival of the Norse," although some remnants of stories that might be associated with the Norse occurred in Wabanaki and Mi'kmaq oral traditions. She accounts that it is relatively common for Mi'Kmaq people in the Miramichi Bay area of New Brunswick to claim Viking ancestry on the basis of occurrance of blue and green eyes within their population though she continues, "from the fifteenth century onward, any number of European fishing fleets hauling cod off the Labrador coast could easily have explored southward into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the large inviting bay of the Miramichi."

Life in Vinland

[edit]The main resources that the people of Vinland relied on were wheat, berries, wine and fish. However, the wheat in the Vinlandic context is sandwort and not traditional wheat, and the grapes mentioned are native North American grapes, because the European grape (Vitis vinifera) and wheat (Triticum sp.) existing in the New World before the Viking arrival in the tenth century is highly unlikely.[47] Both the sagas reference a river and a lake that had an abundance of fish. The sagas specifically mention salmon, and note how the salmon that was encountered was larger than any salmon they had seen before. Before arriving in Vinland, the Norsemen imported their lumber from Norway while in Greenland and had occasional birch trees for firewood. Therefore, the timber they acquired in North America increased their supply of wood.[48]

Other possible Norse finds

[edit]An authentic late-11th-century Norwegian silver penny, with a hole for stringing on a necklace, was found in Maine. Its discovery by an amateur archaeologist in 1957 is controversial; questions have been raised whether it was planted as a hoax.[49] Numerous artifacts attributed to the Norse have been found in Canada, particularly on Baffin Island and in northern Labrador.[50][51]

Other claimed Norse artifacts in the area south of the St. Lawrence include a number of stones inscribed with runic letters. The Kensington Runestone was found in Minnesota, but is generally considered a hoax. The authenticity of the Spirit Pond runestones, recovered in Phippsburg, Maine, is also questioned. Other examples are the Heavener Runestone, the Shawnee Runestone, and the Vérendrye Runestone. The age and origin of these stones is debated, and so far none has been firmly dated or associated with clear evidence of a medieval Norse presence.[52] In general, script in the runic alphabet does not in itself guarantee a Viking age or medieval connection, as it has been suggested that Dalecarlian runes have been used until the 20th century.

Point Rosee, on the southwest coast of Newfoundland, was thought to be the location of a possible Norse settlement. The site was discovered through satellite imagery in 2014 by Sarah Parcak.[53][54] In their November 8, 2017, report, which was submitted to the Provincial Archaeology Office in St. John's, Newfoundland,[55] Sarah Parcak and Gregory "Greg" Mumford wrote that they "found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period"[56] and that "None of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area as having any traces of human activity."[57]

See also

[edit]- L'Anse aux Meadows

- Blackberry

- Vitis labrusca

- Antillia

- Great Ireland (Hvítramannaland)

- Norse colonization of the Americas

- Point Rosee

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories

- Saint Brendan's Island, a hypothetical area that is thought by some to be located in North America.

- Vinland map

- Vinland the Good

- Vinland Saga, a Japanese manga series

Notes

[edit]- ^ "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Laurence Marcellus Larson in Canute the Great: 995 (circ.)-1035 and the Rise of Danish Imperialism During the Viking Age, New York: Putnam, 1912 p. 17

- ^ Elizabeth Janeway in The Vikings, New York, Random House, 1951 throughout

- ^ a b Danver, Steven L. (2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. Vol. 4. ABC-CLIO. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0.

- ^ William C. Wonders (2003). Canada's Changing North. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-7735-7132-7.

- ^ Sigurdsson, Gisli (2008). The Vinland Sagas. London: Penguin. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-140-44776-7. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

The sagas are still our best proof that such voyages to the North American continent took place. Coincidence or wishful thinking simply cannot have produced descriptions of topography, natural resources and native lifestyles unknown to people in Europe that can be corroborated in North America.

- ^ a b c d "L'Anse aux Meadows". L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

Here [L'Anse aux Meadows] Norse expeditions sailed from Greenland, building a small encampment of timber-and-sod buildings …

- ^ Ingstad, Helge; Ingstad, Anne Stine (2001). The Viking Discovery of America: The Excavation of a Norse Settlement in L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland. Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-4716-2.

- ^ a b c "Is L'Anse aux Meadows Vinland?". L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. 2003. Archived from the original on 22 May 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Significance of the discovery of butternut shells at L'Anse aux Meadows: Birgitta Wallace, "The Norse in Newfoundland: L'Anse aux Meadows and Vinland", The New Early Modern Newfoundland: Part 2 (2003), Vol. 19, No. 1. "Many scholars have dismissed L’Anse aux Meadows as peripheral in the Vinland story (Kristjánsson 2005:39). I myself held that view for a long time. I am now contending that L’Anse aux Meadows is in fact the key to unlocking the Vinland sagas. Two factors crystallized this idea in my mind. One was my subsequent research into early French exploitation outposts in Acadia (Wallace 1999) and the nature of migration (Anthony 1990) [...] The second signal was the identification of butternut remains in the Norse stratum at L’Anse aux Meadows. Here was the smoking gun that linked the limited environment of northern Newfoundland with a lush environment in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where wild grapes did indeed exist. The mythical Vinland had a basis in archaeological fact." Birgitta Wallace, "L’Anse aux Meadows, Leif Eriksson’s Home in Vinland", Norse Greenland: Selected Papers from the Hvalsey Conference 2008 Journal of the North Atlantic, 2009, 114-125.

- ^ Praeterea unam adhuc insulam recitavit a multis in eo repertam occeano, quae dicitur Winland, eo quod ibi vites sponte nascantur, vinum optimum ferentes. Some manuscripts have the gloss id est terra vini. M. Adam Bremensis Lib. IV, Cap. XXXVIIII, ed. B. Schmeidler 1917, p. 275 Archived 2015-07-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ c.f. the alternative English name for blueberry is whinberry or winberry. Henley, Jon. Bilberries: the true taste of northern England The Guardian, 9 June 2008.

- ^ "Professor Sven Söderberg om Vinland", Sydsvenska Dagbladet Snällposten, Nr. 295, 30 October 1910. "On a philological basis it can hardly be determined whether the first member is to be interpreted as "vine", as most have done, or as "pasture, meadow"." Sverre Marstrander, "Arkeologiske funn bekrefter sagaens Vinlandsberetninger", Forskningsnytt, XIX:3 (1974), 2-11.

- ^ It remains a common place-name element in Scandinavia, e.g. in Bjørgvin and Granvin, also "possibly in a kenning for Sjaelland, viney, where we have no means of knowing exactly what it implies" (Haugen 1977). A cognate name also existed in Old English (Anglo-Saxon), in the name of the village Woolland in Dorset, England: this was written "Winlande" in the 1086 Domesday Book, and it is interpreted as "meadow land" or "pasture land".[according to whom?]

- ^ "Was Vinland in Newfoundland", Proceedings of the Eighth Viking Congress, Arhus. 24–31 August 1977, ed. Hans Bekker-Nielsen, Peter Foote, Olaf Olsen. Odense University Press. 1981.[1]. See also Kirsten A. Seaver, Maps, Myths and Men. The story of the Vinland Map, Stanford University Press, p. 41.

- ^ Seaver, Kirsten A. (1996). The Frozen Echo. Stanford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-8047-2514-4.

- ^ P. B. Taylor, "The Hønen runes: A survey", Neophilologus Volume 60, Issue 1 (January 1976), pp 1-7. See also: Text and translation of the copy Archived 2015-01-28 at the Wayback Machine Geirodden.com; C. Cavaleri (2008), "The Vínland Sagas as Propaganda for the Christian Church: Freydís and Gudríd as Paradigms for Eve and the Virgin Mary" Master's thesis, University of Oslo.

- ^ Vinland and Ultima Thule. John Th. Honti. Modern Language Notes Vol. 54, No. 3 (Mar., 1939), pp. 159-172 Jstor.org

- ^ a b Jónas Kristjánsson et al. (2012) Falling into Vínland. Acta Archeologica 83, pp. 145-177

- ^ Jane Smiley, “The Sagas of the Greenlanders and The Saga of Eirik the Red” in The Sagas of the Icelanders (New York: Penguin, 2005), 672.

- ^ based on translations by Keneva Kunz, with table of story element comparisons, in "The Sagas of Icelanders", London, Allen Lane (2000) ISBN 0-7139-9356-1

- ^ "Where is Vinland?". www.canadianmysteries.ca. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "A monk in 14th-century Italy wrote about the Americas". The Economist. 25 September 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Merrill, William Stetson. “The Vinland Problem through Four Centuries.” The Catholic Historical Review 21, no. 1 (April 1935):26.JSTOR.

- ^ Livingston, Michael (March 2004). "More Vinland maps and texts". Journal of Medieval History. 30 (1): 25–44. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2003.12.001. S2CID 159749720.

- ^ translations in: B.F. de Costa, Pre-Columbian Discovery of America by the Northmen Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine, Albany NY, Munsell, 1890

- ^ "Historia Norwegiae" (PDF).

- ^ chronicle entries translated in A.M. Reeves et al. The Norse Discovery of America (1906) via sacred-texts.com

- ^ McManis D. 1969. The Traditions of Vinland. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 59(4) DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1969.tb01812.x

- ^ Kaups M, Some Observations on Vinland, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Volume 60, Issue 3, pages 603–609, September 1970. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1970.tb00746.x

- ^ Jørgensen, Dolly (12 January 2009). "A review of the book Isolated Islands in Medieval Nature, Culture and Mind". The Medieval Review. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013.

- ^ Wahlgren, Erik (1986). The Vikings and America. Thomas and Hudson. p. 157.

- ^ Grenfell, Sir Wilfred Thomason (1934). The Romance of Labrador (1st ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishers. p. 61.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Eirik The Red's Saga:, by The Rev. J. Sephton". www.gutenberg.org.

- ^ R. Cleasby & G. Vigfusson An Icelandic-English Dictionary (1874) via the Germanic Lexicon Project

- ^ Munn, William A. (1914). Location of Helluland, Markland, and Vinland from the Icelandic Sagas. St. John's, Newfoundland: Gazette Print. p. 11. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Where is Vinland: L'Anse aux Meadows Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at canadianmysteries.ca

- ^ Dunham, Will (20 October 2021). "Goodbye, Columbus: Vikings crossed the Atlantic 1,000 years ago". Reuters. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Regal, Brian (November–December 2019). "Everything Means Something in Viking". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 43, no. 6. Center for Inquiry. pp. 44–47.

- ^ Gisli Sigurdsson, "The Quest for Vinland in Saga Scholarship", in William Fitzhugh & Elizabeth Ward (Eds.) Vikings: the North Atlantic Saga, Washington DC, Smithsonian Institution (2000) ISBN 1-56098-995-5

- ^ Cartier, Jacques (1863). Voyage de J. Cartier au Canada.

- ^ COSEWIC report on Juglans cinerea (butternut) in Canada[permanent dead link][year needed][dead link]

- ^ Frakes, Jerold C., “Vikings, Vínland and the Discourse of Eurocentrism.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 100, no. 2 (April, 2001):197

- ^ Jakobsson, Sverrir (Winter 2012). "Vínland and Wishful Thinking: Medieval and Modern Fantasies". Canadian Journal of History. 47 (3): 493–514. doi:10.3138/cjh.47.3.493.

- ^ Crocker, Christopher (Spring–Autumn 2020). "What We Talk about When We Talk about Vínland: History, Whiteness, Indigenous Erasure, and the Early Norse Presence in Newfoundland". Canadian Journal of History. 55 (1–2): 91–122. doi:10.3138/cjh-2019-0028.

- ^ Kolodny, Anette (29 May 2012). In Search of First Contact: The Vikings of Vinland, the Peoples of the Dawnland, and the Anglo-American Anxiety of Discovery. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822352860.

- ^ Frakes, Jerold C., “Vikings, Vínland and the Discourse of Eurocentrism.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 100, no. 2 (April, 2001): 175

- ^ Hoidal, Oddvar K., “Norsemen and the North American Forests.” Journal of Forest History 24, no.4 (October, 1980): 201.

- ^ Edmund S. Carpenter, "Norse Penny", New York (2003); See also the critical book review of Bruce Bourque’s "Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine", published in "American Anthropologist" 104 (2): 670-72, and Prins, Harald E.L., and McBride, Bunny, "Asticou's Island Domain: Wabanaki Peoples at Mount Desert Island 1500-2000." (National Park Service) nps.gov

- ^ Pringle, Heather (19 October 2012). "Evidence of Viking Outpost Found in Canada". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ "Strangers, Partners, Neighbors? Helluland Archaeology Project: Recent Finds". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ William W. Fitzhugh & Elizabeth I. Ward (Eds), "Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga", Washington DC, Smithsonian Books (2000) ISBN 1-56098-995-5

- ^ Kean, Gary (2 April 2016). "Update: Archaeologist thinks Codroy Valley may have once been visited by Vikings". The Western Star. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Strauss, Mark (31 March 2016). "Discovery Could Rewrite History of Vikings in New World". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016.

- ^ Parcak, Sarah; Mumford, Gregory (8 November 2017). "Point Rosee, Codroy Valley, NL (ClBu-07) 2016 Test Excavations under Archaeological Investigation Permit #16.26" (PDF). geraldpennyassociates.com, 42 pages. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

[The 2015 and 2016 excavations] found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period. […] None of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area [Point Rosee] as having any traces of human activity.

- ^ McKenzie-Sutter, Holly (31 May 2018). "No Viking presence in southern Newfoundland after all, American researcher finds". The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

An archaeological report presented to the provincial government says there are no signs of a Norse presence in the Point Rosee area in the Codroy Valley. The report on the archaeological work carried out in the area in 2015 and 2016 failed to turn up any signs of Norse occupation, with "no clear evidence" of human occupation before 1800.

- ^ Bird, Lindsay (30 May 2018). "Archeological quest for Codroy Valley Vikings comes up short - Report filed with province states no Norse activity found at dig site". CBC. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

An archeological team searching for a Norse settlement at Point Rosee in the Codroy Valley has come away empty-handed, according to a project report submitted to the province. […] Parcak and Mumford led digs at Point Rosee during the summers of 2015 and 2016, along the way attracting media attention from PBS to the New York Times […]

References

[edit]- Hermann, Pernille (2021). "The Horror of Vínland: Topographies and Otherness in the Vínland sagas". Scandinavian Studies. 93: 1–22. doi:10.3368/sca.93.1.0001.

- Jones, Gwyn (1986). The Norse Atlantic Saga: Being the Norse Voyages of Discovery and Settlement to Iceland, Greenland, and North America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285160-8.

- Sverrir Jakobsson, "Vínland and Wishful Thinking: Medieval and Modern Fantasies," Canadian Journal of History (2012) 47#3 pp 493–514.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Parks Canada - L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Vikings: The north Atlantic saga; Searching for archeological evidence of Vikings in Labrador and Newfoundland Archived 2003-12-09 at the Wayback Machine - from The Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History

- The Vinland Mystery - a National Film Board of Canada documentary

- "Where is Vinland?", Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History website Archived 21 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Skálholt Map - in the Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark

- Full text of Eirik the Red's Saga[permanent dead link]