Battle on the Ice

| Battle on the Ice Battle of Lake Peipus/Chud | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Northern Crusades | |||||||||

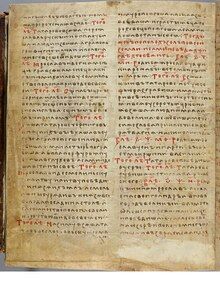

Depiction of the battle in the late 16th century illuminated manuscript Life of Alexander Nevsky | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Livonian Order Bishopric of Dorpat |

Novgorod Republic Principality of Vladimir | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Hermann of Dorpat |

Alexander Nevsky Andrey Yaroslavich | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

from 200–400[b] to as much as 1,800:

|

from 400–800[b] to as many as 6,000–7,000: | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Livonian Rhymed Chronicle: 20 knights killed 6 knights captured Novgorod First Chronicle: 400 Germans killed 50 Germans imprisoned "Countless" Estonians killed[1] | No exact figures | ||||||||

The Battle on the Ice,[c] also known as the Battle of Lake Peipus[d] or Battle of Lake Chud,[e] took place on 5 April 1242. It was fought on the frozen Lake Peipus when the united forces of the Republic of Novgorod and Vladimir-Suzdal, led by Prince Alexander Nevsky, emerged victorious against the forces of the Livonian Order and Bishopric of Dorpat, led by Bishop Hermann of Dorpat.[b]

The outcome of the battle has been traditionally interpreted by Russian historiography as significant for the balance of power between Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox Christianity. It is disputed whether the battle should be considered a "crusade" or not, and whether it represented a significant defeat for the Catholic forces during the Northern Crusades, thus bringing an end to their campaigns against the Orthodox Novgorod Republic and other Rus' territories.[b][4] Estonian historian Anti Selart asserts that the crusades were not an attempt to conquer Rus', but still constituted an attack on the territory of Novgorod and its interests.[5]

Background

[edit]

The origins of the conflict that led to the battle of Lake Peipus in 1242 are unclear and controversial. An influential historiographical tradition has sought to link it to three earlier clashes in the region, all of which Aleksandr Yaroslavich was involved in: the alleged July 1240 Battle of the Neva (only attested in Rus' sources), the September 1240 Izborsk and Pskov campaign, and the winter 1240–1241 Votia campaign.[6]

Researchers have endeavoured to look for Swedish motives to advance into the Neva river basin, often by reference to the letter which Pope Gregory IX sent to the archbishop of Uppsala at the end of 1237, suggesting that a crusade should be held in southwestern Finland against the Tavastians, who allegedly reverted to their pagan beliefs.[7][8][f] On the assumption that a successful 'anti-Tavastian crusade' took place in 1238–39, the Swedes would have advanced further east until they were stopped by a Novgorodian army led by Alexander Yaroslavich, who defeated them in the Battle of the Neva in July 1240, centuries later receiving the nickname Nevsky.[9][7] Nevertheless, this hypothesis resulted in numerous unresolved issues.[10] If the battle did take place, it was probably only a minor clash, in which religion played no role.[8][10] Novgorod would have fought against this incursion for economic reasons, to protect their monopoly of the Karelian fur trade, and access to the Gulf of Finland.[11][g]

Novgorodians had been attempting to subjugate, raid and convert the pagan Estonians (known as Chud') since 1030, when they established the outpost Yuryev (modern Tartu).[13] From the late 12th century, German-Livonian missionary and crusade activity in Livonia and Estonia caused tensions with the Novgorod Republic.[14] The Estonians would sometimes ally with various Rus' principalities against the crusaders, since the eastern Baltic missions constituted a threat to Rus' interests and the tributary peoples.[15] After Novgorod tried to subjugate Lett tribes south of Yuryev in 1212, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword captured Yuryev in 1224,[16] which became the Bishopric of Dorpat's capital.[17] The 1224 peace treaty that the Livonians signed with Pskov and Novgorod was in the latter's favour, and family ties were soon established: prince Vladimir Mstislavich of Pskov (died c. 1227) married off his daughter to Theoderic of Buxhövden, brother of bishops Albert of Riga and Hermann of Dorpat.[18] Vladimir's son Yaroslav would later attempt to become the new prince of Pskov with the help of his brother-in-law, bishop Hermann of Dorpat; they failed in 1233,[19] but succeeded during the September 1240 Izborsk and Pskov campaign.[20][21]

Some time after, in the winter of 1240–1241, the combined forces of the Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek (in modern-day western Estonia) and the Livonian Order launched the 1240–1241 Votia campaign.[22] This campaign may be properly considered a crusade in the sense of a missionary conquest of 'pagan' lands.[23][24][h] It is unknown whether Votia was a tributary of Novgorod at the time,[28] or only became one later.[29] In either case, while the Sword Brothers and bishop Henry of Ösel–Wiek probably did not intend to attack Novgorod, their actions provoked a Novgorodian counterattack in 1241.[30][31] The delayed response was a result of the internal strife in Novgorod.[32] When they approached Novgorod itself, the local citizens recalled to the city 20-year-old Prince Alexander Nevsky, whom they had banished to Pereslavl earlier that year.[33]

During the campaign of 1241, Alexander managed to retake both Votia and Pskov.[34][35][36] Alexander then continued into Estonian-German territory.[32] In the spring of 1242, the Teutonic Knights defeated a detachment of the Novgorodian army about 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of the fortress of Dorpat (now Tartu). As a result, Alexander set up a position at Lake Peipus, where the battle would take place on 5 April 1242.[32]

Accounts in primary sources

[edit]

According to the Livonian Order's Livonian Rhymed Chronicle (written in the 1290s[37]), lines 2235–2262:

sie quâmen zû der brûdere macht. |

die Rûʒen hatten schutzen vil, |

und sach helme schrôten. |

daʒ ie wol sechzic man |

sie mûsten wîchen durch die nôt. |

...[Bishop Henry's men] joined the Brothers' forces. But they had brought along too few people, and the Brothers' army was also too small. Nevertheless they decided to attack the Rus' [Rûʒen]. The latter had many archers. The battle began with their bold assault [in front of] the king's men.[i] The Brothers' banners were soon flying in the midst of the archers, and swords were heard cutting helmets apart. Many from both sides fell dead on the grass [ûf daʒ gras]. Then the Brothers' army was completely surrounded, for the Rus' had so many troops that there were easily sixty men for every one German knight. The Brothers fought well enough, but they were nonetheless cut down. Some of those from Dorpat escaped from the battle, and it was their salvation that they had been forced to flee. Twenty Brothers lay dead and six were captured. Thus the battle ended.[37][40]

According to the Laurentian continuation of the Suzdalian Chronicle (compiled in 1377; the entry in question may originally have been composed around 1310[41]):

Великъıи кнѧз̑ Ӕрославъ посла сн҃а своѥго Андрѣа в Новъгородъ Великъıи в помочь Ѡлександрови на Нѣмци. и побѣдиша ӕ за Плесковом̑ на ѡзерѣ и полонъ многъ плѣниша. и възвратисѧ Андрѣи къ ѡц҃ю своєму с чс̑тью.[42]

Grand Prince Iaroslav sent his son Andrei to Great Novgorod in aid of Alexander against the Germans and defeated them beyond Pskov at the lake (на озере) and took many prisoners. Andrei returned to his father with honor.[41]

According to the Synod Scroll (Older Redaction) of the Novgorod First Chronicle (the entry of which has been dated to c. 1350[37]):

Prince Alexander and all the men of Novgorod drew up their forces by the lake, at Uzmen, by the Raven's Rock; and the Germans [Nemtsy] and the Estonians [Chuds] rode at them, driving themselves like a wedge through their army. And there was a great slaughter of Germans and Estonians... they fought with them during the pursuit on the ice seven versts short of the Subol [north-western] shore. And there fell a countless number of Estonians, and 400 of the Germans, and they took fifty with their hands and they took them to Novgorod.[43]

The Younger Redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle (compiled in the 1440s) increased the amount of "Germans" (Nemtsy) killed from 400 to 500.[44]

The Life of Alexander Nevsky, the earliest redaction of which was dated by Donald Ostrowski to the mid-15th century, combined all the various elements of the Laurentian Suzdalian, Novgorod First, and Moscow Academic (Rostov-Suzdal) accounts.[45] It was the first version to claim that the battle itself took place upon the ice of the frozen lake, that many soldiers were killed on the ice, and that the bodies of dead soldiers of both sides covered the ice with blood.[46] It even states that 'There was ... a noise from the breaking of lances and a sound from the clanging of swords as though the frozen lake moved,' suggesting the clamor of battle somehow stirred the ice, although there is no mention of it breaking.[46] He added that the later textual traditions were likely influenced by earlier accounts of the 1016 Battle of Liubech, which did take place on ice, but the ice neither weakened nor broke in the original story, only in two later interpolations.[47]

Scholarly reconstructions of the battle

[edit]

On 5 April 1242 Alexander, intending to fight in a place of his own choosing, retreated in an attempt to draw the often over-confident Crusaders onto the frozen lake.[33] Estimates on the number of troops in the opposing armies vary widely among scholars. A more conservative estimation by David Nicolle (1996) has it that the crusader forces likely numbered around 2,600, including 800 Danish and German knights, 100 Teutonic knights, 300 Danes, 400 Germans, and 1,000 Estonian infantry.[3] The Novgorodians fielded around 5,000 men: Alexander and his brother Andrei's bodyguards (druzhina), totalling around 1,000, plus 2,000 militia of Novgorod, 1,400 Finno-Ugrian tribesmen, and 600 horse archers.[3]

The Teutonic knights and crusaders charged across the lake and reached the enemy, but were held up by the infantry of the Novgorodian militia.[33] This caused the momentum of the crusader attack to slow. The battle was fierce, with the allied Rus' soldiers fighting the Teutonic and crusader troops on the frozen surface of the lake. After a little more than two hours of close quarters fighting, Alexander ordered the left and right wings of his army (including cavalry) to enter the battle.[33] The Teutonic and crusader troops by that time were exhausted from the constant struggle on the slippery surface of the frozen lake. The Crusaders started to retreat in disarray deeper onto the ice, and the appearance of the fresh Novgorod cavalry made them retreat in panic.[33]

Historical legacy

[edit]The knights' defeat at the hands of Alexander's forces prevented the crusaders from retaking Pskov, the linchpin of their eastern crusade.[48] The battle thus halted the eastward expansion of the Teutonic Order.[49] Thereafter, the river Narva and Lake Peipus would represent a stable boundary dividing Eastern Orthodoxy from Western Catholicism.[50]

Some historians have argued that the launch of the campaigns in the eastern Baltic at the same time were part of a coordinated campaign; Finnish historian Gustav A. Donner argued in 1929 that a joint campaign was organized by William of Modena and originated in the Roman Curia.[51] This interpretation was taken up by Russian historians such as Igor Pavlovich Shaskol'skii and a number of Western European historians.[51] More recent historians have rejected the idea of a coordinated attack between the Swedes, Danes and Germans, as well as a papal master plan due to a lack of decisive evidence.[51] Some scholars have instead considered the Swedish attack on the Neva River to be part of the continuation of rivalry between the Rus' and Swedes for supremacy in Finland and Karelia.[52] Anti Selart also mentions that the papal bulls from 1240 to 1243 do not mention warfare against "Russians", but against non-Christians.[53]

In 1983, a revisionist view proposed by historian John L. I. Fennell argued that the battle was not as important, nor as large, as has often been portrayed. Fennell claimed that most of the Teutonic Knights were by that time engaged elsewhere in the Baltic, and that the apparently low number of knights' casualties according to their own sources indicates the smallness of the encounter.[54] He also said that neither the Suzdalian Chronicle (the Lavrent'evskiy), nor any of the Swedish sources mention the occasion, which according to him would mean that the 'great battle' was little more than one of many periodic clashes.[54] Donald Ostrowski (2006) pointed out that the Suzdalian Chronicle in the Laurentian Codex does bring it up in passing, but "provide[s] only minimal information about the battle."[41]

Cultural legacy

[edit]Tsarist Russia

[edit]Macarius of Moscow canonized Alexander Nevsky as a saint of the Russian Orthodox Church in 1547.[55]

Soviet Russia

[edit]The event was glorified in Sergei Eisenstein's patriotic historical drama film Alexander Nevsky, released in 1938.[56] The movie, bearing propagandist allegories of the Teutonic Knights as Nazi Germans, with the Teutonic infantry wearing modified World War I German Stahlhelm helmets, has created a popular image of the battle often mistaken for the real events.[56] In particular, the image of knights dying by breaking the ice and drowning originates from the film.[57] Sergei Prokofiev turned his score for the film into a concert cantata of the same title, the longest movement of which is "The Battle on the Ice".[58] The editors of the 1977 English translation of the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, Jerry Smith and William Urban, commented that 'Eisenstein's movie Alexander Nevsky is magnificent and worth seeing, but he tells us more about 1939 than 1242.'[59]

Donald Ostrowski writes in his 2006 article Alexander Nevskii's "Battle on the Ice": The Creation of a Legend that accounts of ice breaking and knights drowning are a relatively recent embellishment to the original historical story.[57] None of the primary sources mention ice breaking; the earliest account in the LRC explicitly says killed soldiers "fell on the grass" and the Laurentian continuation that it was "at a lake beyond Pleskov" (rather than "on a lake"). It was not until decades later that more details were gradually added of a specific lake, that the lake was frozen, that the crusaders were chased across the frozen lake, and not until the 15th century that a battle (not just a chase) took place on the ice itself.[57] He cites a large number of scholars who have written about the battle, including Karamzin, Solovyev, Petrushevskii, Khitrov, Platonov, Grekov, Vernadsky, Razin, Myakotin, Pashuto, Fennell, and Kirpichnikov, none of whom mention the ice breaking up or anyone drowning when discussing the battle of Lake Peipus.[57] After analysing all the sources, Ostrowski concludes that the part about ice breaking and drowning first appeared in the 1938 film Alexander Nevsky by Sergei Eisenstein.[57]

In 1958 and 1959, underwater investigations in the northern part of Lake Lämmi (which connects Lake Peipus with Lake Pikhva), where some Soviet researchers presumed the combat happened, failed to find any artefacts connected to the battle of 1242.[60] Given the fact that the oldest sources never mention the battle taking place "on" the lake, let alone that the lake was frozen, that the ice broke and that many soldiers drowned, Ostrowski commented that such a lack of archaeological evidence at the lake's bottom was to be expected.[60]

During World War II, the image of Alexander Nevsky became a national Soviet Russian symbol of the struggle against German occupation.[54] The Order of Alexander Nevsky was established as a military award in the Soviet Union in 1942 during the Great Patriotic War.[61]

Russian Federation

[edit]

The Novgorodian victory is commemorated in the modern Russian Federation as one of the Days of Military Honour.[62]

In 2010, the Russian government amended the statute of the Order of Alexander Nevsky as an award for excellent civilian service to the country.[63]

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to the Novgorod First Chronicle (NPL): "The same year [1242] the Nemtsy ["Germans"] sent with greeting, in the absence of the Knyaz [Alexander]: "The land of the Vod people, of Luga, Pleskov [Pskov], and Lotygola [Latgale], which we invaded with the sword, from all this we withdraw, and those of your men whom we have taken we will exchange, we will let go yours, and you let go ours." And they let go the Pleskov hostages, and made peace."[1]

- ^ a b c d According to Dittmar Dahlmann (2003), footnote 4, the number of combatants vary considerably between the various authors.[2]

- ^ German: Schlacht auf dem Eise; Russian: Ледовое побоище, romanized: Ledovoye poboishche; Estonian: Jäälahing.

- ^ German: Schlacht auf dem Peipussee or am Peipussee.

- ^ Russian: битва на Чудском озере, romanized: bitva na Chudskom ozere.

- ^ The Swedish Erik's Chronicle (written 14th century) does describe a campaign against the Tavastians by Birger Jarl, traditionally called the "Second Swedish Crusade" and dated to 1249–1250. But by the mid-20th century, several historians began to think it should be backdated to 1238–39, in order to follow the 1237 papal letter, but precede the 1240 Neva battle.[7]

- ^ "Novgorod and Sweden were competitors both for dominance over Finnic tribes north of the Novgorod lands and for control over access to the Gulf of Finland. The Swedish attack on the Neva River in July 1240 was one of a long series of hostile encounters over these issues, not, as is sometimes asserted, a full-scale campaign timed to take advantage of the Russians' adversity and aimed at conquering the entire Novgorodian realm. Nevertheless, Alexander's victory there was celebrated and became the basis for his epithet Nevsky."[12]

- ^ A treaty was concluded in 1241 at Riga between the bishop of Ösel–Wiek and the Teutonic Order, which stipulated that the bishop was granted spiritual superiority in the newly conquered territories.[25] It made a comment regarding the pagans still living between Pskov and Novgorod and the Latin Christian settlements in Finland, Estonia and Livonia by writing: "between already converted Estonia and Rus', that is, in Votia, the Neva, Ingria, and Karelia, and hoped for their conversion to the Christian faith"[26] (Latin original: inter Estoniam iam conversam et Rutiam, in terris videlicet Watlande, Nouve, Ingriae et Carelae, de quibus spes erat conversionis ad fidem Christi[27]). The treaty indicated that the crusaders were well aware of the existence of these pagans.[27]

- ^ The phrase kuniges schar ("king's men") refers to the troops of "king" (prince) Aleksandr. It is a misunderstanding that "king's men" refers to troops of the Danish king.[39]

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Life of Alexander Nevsky (c. 1450).[64]

- Livonian Rhymed Chronicle (LRC, c. 1290s).[37]

- Meyer, Leo (1876). Livländische Reimchronik, mit Anmerkungen, Namenverzeichniss und Glossar herausgegeben von Leo Meyer [Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, with Annotations, Index of Names and Glossary, edited by Leo Meyer] (in German). Paderborn. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (Reprint: Hildesheim 1963). Lines 2235–2262. - Smith, Jerry C.; Urban, William L., eds. (1977). The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle: Translated with an Historical Introduction, Maps and Appendices. Uralic and Altaic series. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-87750-213-5.

- Meyer, Leo (1876). Livländische Reimchronik, mit Anmerkungen, Namenverzeichniss und Glossar herausgegeben von Leo Meyer [Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, with Annotations, Index of Names and Glossary, edited by Leo Meyer] (in German). Paderborn. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- Pskov Third Chronicle (1567).

- Savignac, David (2016). The Pskov 3rd Chronicle. 2nd Edition. Edited, translated, and annotated by David Savignac. Crofton: Beowulf & Sons. p. 245. Retrieved 17 September 2024. Entries under the years 1240–1242. Translation based on the 2000 reprint of Nasonov's 1955 critical edition of the Pskov Chronicles.

- "Rostov-Suzdal Compilation" in the Moscow Academic Chronicle (MAk, c. 1500).[65]

- Suzdalian Chronicle, Laurentian continuation (1377), s.a. 6750 (1242).[41]

- Лаврентьевская летопись [Laurentian Chronicle]. Полное Собрание Русских Литописей [Complete Collection of Rus' Chronicles] (in Church Slavic). Vol. 1. Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House. 1926–1928.

- Synod Scroll (Older Redaction) of the Novgorod First Chronicle (c. 1275), s.a. 6750 (1242).[66]

- Michell, Robert; Forbes, Nevill (1914). The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016–1471. Translated from the Russian by Robert Michell and Nevill Forbes, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford, with an introduction by C. Raymond Beazley and A. A. Shakhmatov (PDF). London: Gray's Inn. p. 237. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

Literature

[edit]- Dahlmann, Dittmar (2003). "Der russische Sieg über die „teutonischen Ritter" auf dem Peipussee 1242" [The Rus' victory over the "Teutonic Knights" at Lake Peipus 1242]. In Krumeich, Gerd; Brandt, Susanne (eds.). Schlachtenmythen. Ereignis–Erzählung–Erinnerung [Battle Myths: Event, Narrative, Memory] (in German). Cologne/Vienna: Böhlau. pp. 63–75. ISBN 3-412-08703-3.

- Fennell, John (2014) [1983]. The Crisis of Medieval Russia 1200–1304. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-582-48150-3.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben (2007). The popes and the Baltic crusades, 1147–1254. Brill. ISBN 9789004155022.

- Hellie, Richard (2006). "Alexander Nevskii's April 5, 1242 Battle on the Ice". Russian History/Histoire Russe. 33 (2/4). Brill: 283–287. doi:10.1163/187633106X00177. JSTOR 24664445 – via JSTOR.

- Isoaho, Mari (2006). The Image of Aleksandr Nevskiy in Medieval Russia: Warrior and Saint. Leiden: Brill. p. 428. ISBN 9789047409496. Retrieved 13 December 2024. (public version of PhD dissertation).

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Second Edition. E-book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36800-4.

- Murray, Alan V. (2017). Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150–1500. Taylor & Francis. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-351-94715-2.

- Nicolle, David (1996). Lake Peipus 1242: Battle of the Ice. Osprey Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9781855325531.

- Ostrowski, Donald (2006). "Alexander Nevskii's 'Battle on the Ice': The Creation of a Legend". Russian History/Histoire Russe. 33 (2/4). Brill: 289–312. doi:10.1163/187633106X00186. ISSN 0094-288X. JSTOR 24664446.

- Raffensperger, Christian; Ostrowski, Donald (2023). The Ruling Families of Rus: Clan, Family and Kingdom. London: Reaktion Books. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-78914-745-2. (e-book)

- Selart, Anti (2015). "Chapter 3: Livonia and Rus' in the 1230s and 1240s". Livonia, Rus' and the Baltic Crusades in the Thirteenth Century. Leiden/Boston: BRILL. pp. 127–170. doi:10.1163/9789004284753_005. ISBN 978-90-04-28475-3.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Michell & Forbes 1914, p. 87.

- ^ Dahlmann 2003, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d Nicolle 1996, p. 41.

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2003. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Selart, Anti (2001). "Confessional Conflict and Political Co-operation: Livonia and Russia in the Thirteenth Century". Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150–1500. Routledge. pp. 151–176. doi:10.4324/9781315258805-8. ISBN 978-1-315-25880-5.

- ^ Selart 2015, pp. 143–147.

- ^ a b c Selart 2015, p. 150.

- ^ a b Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 216–217, The Russian victory was later depicted as an event of great national importance and Prince Alexander was given the sobriquet "Nevskii".

- ^ a b Selart 2015, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Andrew Jotischky (2017). Crusading and the Crusader States. Taylor and Francis. p. 220. ISBN 9781351983921.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 180.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 49.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 139.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 216, The missions in the eastern Baltic constituted a threat to the Russians of Novgorod and Pskov, their tributary peoples and their interests in the region..

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 140.

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 142.

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 129.

- ^ Selart 2015, pp. 134–136.

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 159.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 220, The campaign against Izborsk and Pskov was a purely political undertaking... the co-operation between the exiled Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich of Pskov and the men from the bishopric of Dorpat..

- ^ Martin 2007, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 220, The campaigns to the River Neva and into Votia were... crusades aiming at expanding the Catholic Church..

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 159, The actions of the Teutonic Order in Votia in 1240 most probably aimed first and foremost at continuing the missionary conquest of the ‘pagan’ areas of the region..

- ^ Murray 2017, p. 164.

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 156.

- ^ a b Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 220.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 218, In the winter of 1240–41, a group of Latin Christians invaded Votia, the lands north-east of Lake Peipus which were tributary to Novgorod..

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 156, It is not clear how secure Novgorod's control was in Votia at the time (...) There are a number of references to Votia's dependence on Novgorod from the second half of the 13th century. It is nevertheless unknown how much of Votia fell within this dependency c. 1240.".

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218, The Novgorodian counterattack came in 1241..

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 159, While it did indeed provoke the conflict with Novgorod, it was not aimed against a ‘schismatic’ enemy..

- ^ a b c Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218.

- ^ a b c d e Hellie 2006, p. 284.

- ^ Martin 2007, pp. 175–219.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218, After pleas from Novgorod Alexander returned in 1241 and marched against Kopor'e. Having conquered the fortress and captured the remaining Latin Christians, he executed those local Votians who had cooperated with the invaders..

- ^ Murray 2017, p. 164, These conquests were lost in 1241–42, when the Russians destroyed Kopor'e..

- ^ a b c d Ostrowski 2006, p. 291.

- ^ Meyer 1876, p. 52.

- ^ Selart 2015, p. 162.

- ^ Smith & Urban 1977, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b c d Ostrowski 2006, p. 293.

- ^ "Въ лЂто 6745 [1237] — въ лЂто 6758 [1250]. Лаврентіївський літопис" [In the year 6745 [1237] – 6758 [1250]. The Laurentian Codex]. litopys.org.ua (in Church Slavic). 1928. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ Christiansen, Eric (4 December 1997). The Northern Crusades. Penguin UK. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-14-193736-6.

- ^ Ostrowski 2006, p. 298.

- ^ Ostrowski 2006, pp. 298–299.

- ^ a b Ostrowski 2006, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Ostrowski 2006, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Riley-Smith Jonathan Simon Christopher. The Crusades: a History, US, 1987, ISBN 0300101287, p. 198.

- ^ Riley-Smith Jonathan Simon Christopher. The Crusades: a History, US, 1987, ISBN 0300101287, p. 198.

- ^ Hosking, Geoffrey A. Russia and the Russians: a history, US, 2001, ISBN 0674004736, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 219.

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 219, Some scholars therefore regard the Swedish attack on the River Neva as merely a continuation of the Russo-Swedish rivalry..

- ^ Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 219–220, Selart stresses, none of the papal bulls of 1240–43 mention warfare against the Russians. They only refer to the fight against non-Christians and to mission among pagans.

- ^ a b c Fennell 2014, p. 106.

- ^ Raffensperger & Ostrowski 2023, p. 125.

- ^ a b "Alexander Nevsky and the Rout of the Germans". The Eisenstein Reader: 140–144. 1998. doi:10.5040/9781838711023.ch-014. ISBN 9781838711023.

- ^ a b c d e Ostrowski 2006, pp. 289–312.

- ^ Danilevsky, Igor (22 May 2015). Ледовое побоище (in Russian). Postnauka. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Smith & Urban 1977, p. 32.

- ^ a b Ostrowski 2006, p. 312.

- ^ "Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of July 29, 1942" (in Russian). Legal Library of the USSR. 1942-07-29. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ^ "Федеральный закон от 13.03.1995 г. № 32-ФЗ".

- ^ "Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of September 7, 2010 No 1099" (in Russian). Russian Gazette. 2010-09-07. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ^ Ostrowski 2006, p. 299.

- ^ Ostrowski 2006, p. 294.

- ^ Ostrowski 2006, pp. 295–296.

Further reading

[edit]- Military Heritage did a feature on the Battle of Lake Peipus and the holy Knights Templar and the monastic knighthood Hospitallers (Terry Gore, Military Heritage, August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp. 28–33), ISSN 1524-8666.

- John France, Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades 1000–1300. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Anti Selart. Livland und die Rus' im 13. Jahrhundert. Böhlau, Köln/Wien 2012, ISBN 9783412160067. (in German)

- Kaldalu, Meelis; Toots, Timo, Looking for the Border Island. Tartu: Damtan Publishing, 2005. Contemporary journalistic narrative about an Estonian youth attempting to uncover the secret of the Ice Battle.