List of bog bodies

This is a list of bog bodies grouped by location of discovery. Bog bodies, or bog people, are the naturally preserved corpses of humans and some animals recovered from peat bogs. The bodies have been most commonly found in the Northern European countries of Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Ireland. Reports of bog bodies surfaced during the early 18th century.[1]

In 1965, the German scientist Alfred Dieck catalogued more than 1,850 bog bodies, but later scholarship revealed much of Dieck's work was erroneous.[2] Hundreds of bog bodies have been recovered and studied,[3] although it is believed that only around 45 remain intact today.[4]

How to use this list

[edit]- There may be more than one name in the "name" category, which may also be used to show alternate spellings for names of the bog body.

- The location category shows the city or state in which the bog body was discovered, although some bog bodies are discovered on borders between countries.

- The carbon-14 dating is used to determine an age range based on examination of the half lives of carbon isotopes.

- The "sex" category describes whether the find was male, female, or undetermined.

- The "description" category depicts examination details as well as physical characteristics of the body. Some sections may state Little is published about this find, meaning that there is little or no sufficient information published about the bog body.

List

[edit]Denmark

[edit]| Name | Other names | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arden Woman | Bredmose Woman | Himmerland | 1400 BCE | Female | 1942 |

|

The Arden Woman was found in the Bredmose bog in the Parish of Store Arden, Hindsted, Denmark. Police said the corpse was found in a 'question mark' shape. After the remains were completely unearthed they were moved into a nearby barn. Her hair was dark blond and was drawn into two pigtails and coiled around the top of her head. Over the hair was a bonnet, which was made using a sprang technique. Unlike some bog bodies, she was found with other garments. She was around the age of 20–25 years old. No signs of violence were found on her body.[5] The body remains at the National Museum of Copenhagen.[6] |

| Auning Woman | Midtjylland | 1st century BC/AD | Female | 1886 | She was found with several wool and skin garments. Because she was found with several sticks on top of her body, it may be possible that she had been pinned down in the bog to keep her remains from surfacing.[5] | ||

| Borremose Man | Borre Fen Man | Himmerland | 700 BCE | Male | 1946 |

|

The man was found with his skull crushed and his leg broken. A rope was also found around his neck, indicating death by hanging or strangulation.[7][8] Examination of bog bodies such as Cashel Man have led scientists to speculate that wounds such as broken bones may have occurred after death due to the weight of the peat.[9] The body is in storage at the National Museum of Copenhagen.[7] |

| Borremose II | Himmerland | 400 BCE | Presumed Female | 1947 |

|

The bog body was lying face down at a depth of two feet on a base of birch bark. Birch branches were also found in the immediate vicinity and, directly on top of the body, were three approximately 10-centimeter-long birch poles of the same thickness. The skull was fractured and the brain was visible. The right leg was broken ten inches below the knee, which was caused by the weight of peat on the body.[10] The upper body was naked, but the lower body and legs were covered by a cloak made of a four-layered twill fabric and a fringed shawl. These two articles of clothing are now on display at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. In addition, there were other objects found with her: half a clay pot, placed on the knees of the corpse, along with half a humerus and half a radius of a human infant beside her. Around the neck of the bog body was a leather belt with an amber bead and a brass disk 22–23 millimeters in diameter.[8] | |

| Borremose III | Borremose Woman | Himmerland | 750 BCE | Female | 1948 |

|

The Borremose Woman was discovered lying face down with the scalp separated from the body. The woman was described as being obese, and was wrapped in a woolen cloak. Borremose Woman is not currently on display, but is stored at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. The age of the woman at the time of her death was approximately 20–35 years old.[10] Like the other Borremose discoveries, the woman appeared to have violent injuries.[8] She was previously thought to have been scalped as well as having her skull crushed as the cause of death, but studies show these happened after death due to movement of the peat in the bog.[8][10] Studies of the woman's face and neck showed no signs of bleeding, meaning that the injuries to the face had occurred after death.[11] |

| Elling Woman | Silkeborg | 280 BCE | Female | 1938 |

|

The body was wrapped in a sheepskin cape with a leather cloak tied around the woman's legs.[8][12] The face of the woman was poorly preserved as well as no traces of organs inside of the body.[13] The woman was hanged like the Tollund Man, who was found in the same bog twelve years later. This body is often recognized by its 90 centimeter braid, which was tied into an elaborate knot.[8][13] Elling Woman is believed to have been a human sacrifice.[14] | |

| Frær Mose Foot | Frærmose Woman | Denmark | Undetermined | Male | 1842 | The foot was unearthed four feet under the surface of the bog. A well preserved wool garment and a shoe were found with the human remains.[15] The foot was initially thought to have belonged to a woman based on its small size, but recent studies now suggest that the foot belonged to a man.[16] | |

| Gadevang Man | Zealand | 480–60 BCE[17] | Male | 1940 | This bog body was found completely skeletonized. Examination revealed that he was approximately 35–50 years of age at the time of his death. A hole in his skull shows evidence of primitive surgery.[18] | ||

| Grauballe Man | Jutland | 290 BCE | Male | 1952 |

|

Studies show Grauballe Man was most likely a ritual sacrifice victim. His fingers had been so perfectly preserved in the bog that researchers were able to take his fingerprints. The man's face has been reconstructed to show what he had looked like when he was alive.[8][19] | |

| Haraldskær Woman | Haraldskjaer Woman | Jutland | 500–401 BCE | Female | 1835 |

|

For some time, The Haraldskær Woman was thought to have been the Norwegian Queen Gunnhild, until carbon-14 dating proved she was much older. Studies show she was around 50 years old and in good health when she died. Her clothing was placed on top of her naked body.[20][21] |

| Huldremose Woman | Huldre Fen Woman, Huldre Woman | Ramten, Midtjylland | 160 BCE–340 CE | Female | 1879 |

|

Huldremose Woman is the name of the bog body of an Iron Age woman discovered in 1879 near Ramten, Jutland. The body, found clothed in a wool skirt and two skin capes, dated between 160 BCE and 340 CE. At the time of death, the woman was more than 40 years old.[22] Her right arm was severed, but the injury probably occurred by shovels during the unearthing of the body. A wool cord tied her hair and enveloped her neck, but forensic analysis found no indication of death by strangulation.[23]

According to recent isotope analysis, parts of her clothing's wool had been imported from northern Norway or Sweden.[24] |

| Nederfrederiksmose body | Kraglund Man, Frederiksdal Man | Nordjylland | 1040–1155 AD | Presumed male | 1898 |

|

The first bog body to be photographed before being moved from where it was discovered.[25][26] |

| Koelbjerg Man | Syddanmark | 8000 BCE | Male | 1941 | Thought to be the oldest bog body to date,[27] he was around 25 years of age when he died. There were no traces of violence found on the skeletal remains. According to DNA analysis the body, previously believed to be that of a woman, is actually male.[28] | ||

| Porsmose Man | Zealand | 2600 BCE | Male | 1946 |

|

This skeletonized bog body was that of a 35–40-year-old man[29] that was found in 1946. The skeleton is most famous for the arrowhead which pierced the man's nose, but he was not killed by this wound; but rather by an arrow that pierced his aorta. The arrows are presumed to have been shot from a close distance and from above.[29] | |

| Rappendam Woman | Frederiksborg | 160 BCE | Female | 1941–1942 |

|

The skeletonized remains were discovered along with birch hazel sticks with wooden wheels.[30] | |

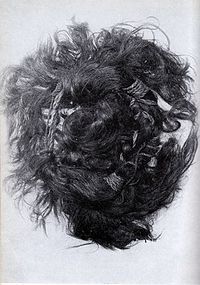

| Roum Man | Roum Woman | Himmerland | Iron Age | Male[31][32] | 1942 |

|

Only the severed head of the body was found. The young man was around 20 years old at the time he died. The find was originally titled as "Roum Woman" until traces of beard stubble were found on the face.[31] The sheepskin that the head was wrapped in dates to the early Iron Age.[5] |

| Sigersdal Skeletons | Zealand | 3650–3140 BCE | Presumed male[33] | 1949 | These two people were around 16 and 19 when they died. One skull had a very large trauma wound on its left side.[34] | ||

| Søgårds Mose Man (I) | Jutland | 356 BCE – 116 CE | Male | 1942 | The body of a man found next to three sheepskin capes, calfskin shoes and a dog's skin cap.[35] | ||

| Søgårds Man (II) | Jutland | 1944 | Only the arms and legs of the body were preserved.[36] | ||||

| Sorø Skeletons | Lolland | 3500 BCE | Male | 1942 | The collective name for two skeletons with deformities and evidence of surgery.[37] | ||

| Stidsholt Woman | Stidsholtmose Woman | Jutland | Undetermined | Female | 1859 |

|

The Stidsholt Woman is the severed head of a woman discovered in 1859.[38][39] She was decapitated by a blow to the third and fourth vertebrae. Her hair is a dark red, which comes from the chemicals in peat bogs. Her hair had been tied into a knot, and fastened with a woven band, which was destroyed.[38][39] Her head was never scientifically dated, and the rest of her body was never found.[38] Her hair was 51 cm (20 inches) long. She is also known as the Stidsholt Fen Woman and the Stidsholtmose Woman.[39] Her head is on display in the Copenhagen Museum in Denmark.[40] |

| Tollund Man | Silkeborg | 400 BCE | Male | 1950 |

|

The Tollund Man has been noted for the excellent preservation of his facial features. The corpse was found in early May 1950 when a family had been harvesting peat from a bog, near the town of Silkeborg. With the body, a sheepskin cap and a belt were found, although no additional article of clothing was preserved, probably because they had decomposed. He also had a noose around his neck, indicating that he was hanged. Only his head remains original in his museum display due to lack of preservation knowledge at the time of discovery. It is believed that the Tollund Man was a ritual sacrifice victim.[41]

The Elling Woman had been discovered twelve years earlier, hanged as well, 80 meters from his discovery site.[14] | |

| Valmose bodies | Jutland | 380 BCE and 225-230 BCE | Female | Unknown | Two adult skeletons of women were found with fragments of pottery and two other incomplete human skeletons of undetermined genders. A vast amount of animal remains were also found, including horses and oxen.[42] | ||

| Vester Thorsted Man | Vejle | 145 – 95 BCE | Male | 1913 | The man's body was discovered wearing a leather cloak, two feet below the surface of the bog.[43] | ||

| Vittrup Man | Vittrup | 3100 - 3300 BCE | Male | 1915 | The man's right anklebone, lower left shinbone, jawbone and fragmented skull were found in the bog. Researchers estimate he was hit over the head at least eight times with a wooden club that was found with the skeletal fragments. He lived on the coast of the Scandinavian Peninsula in a society of hunter-gatherers until he was 18 or 19, then lived in a community of farmers in Denmark until he was killed between the ages of 30 and 40.[44] |

Germany

[edit]| Name | Other names | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahlintel Man | North Rhine-Westphalia | Undetermined | Male | 1794 | [45] | ||

| Girl of the Bareler Moor | Lower Saxony | 260–395 CE | Female | 1784 |

|

Due to the over-sampling of the remains, only the skin of the right side of the chest has survived today (marked red on image). | |

| Bentstreek leg | Bentstreek foot | Lower Saxony | 80–210 CE | Undetermined | 1955 | The leg was thought to have been lying above ground for months before it was discovered.[46] | |

| Bernuthsfeld Man | Lower Saxony | 680–775 CE | Male | 1907 |

|

Bernuthsfeld Man was discovered on 24 May 1907 when peat workers unearthed his skeleton and clothing. His heavily worn tunic was patched out of 45 single pieces of cloth, out of 20 different fabrics in 9 different weaving patterns.[47] | |

| Borsteler Moor body | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1921 | [48] | ||

| Bremervörde Gnattenbergswiesen body | Lower Saxony | 634–689 CE | Presumed Female | 1934 |

|

An incomplete early medieval bog skeleton. | |

| Bunsoh Man | Bunsoh body | Schleswig-Holstein | 560–620 CE | Male | 1890 |

|

The corpse was discovered 100 cm below the surface of the bog on 17 May 1890 by peat workers. Along with a woolen textile (pictured), many birch branches were found over the body. After the body had been moved to storage, it had decomposed severely. It is unknown what the cause of death was, although it is thought by some that the type of textile was used as a garrote or for strangulation.[49] |

| "Bog Dog" | Bog dog from Burlage | Lower Saxony | 1477–1611 CE | Male | 1953 | The dog's fur remains well preserved, colored reddish after being in the bog for so long. The skeleton remains intact, despite parts of the skull that are missing. The dog was believed to have been from around juvenile to adult when he died.[50] | |

| Damendorf I | Damendorf Woman | Schleswig-Holstein | Pre-Roman Iron Age | Presumed Female | 1884 | Only the clothing of this bog body has survived.[51] | |

| Damendorf Man | Damendorf II | Schleswig-Holstein | 300 BCE | Male | 1900 |

|

Damendorf Man is currently on display at the Archäologisches Landesmuseum in Schleswig, Germany. The weight of the peat in the bog had flattened his body with only traces of bone left.[1]

Hair, skin, nails, and his few clothes were also preserved.[52] He was found with a leather belt, shoes, and a pair of breeches.[53] |

| Damendorf Girl[51] | Schleswig-Holstein | 810 BCE | Female | 1934 | The body of an approximately 14-year-old girl was found along with some clothing.[54] | ||

| Dätgen I | Schleswig-Holstein | Iron Age | Undetermined | 1906 | Only the clothing of the body has survived. Little is published about this find. | ||

| Dätgen Man | Schleswig-Holstein | 135–385 CE | Male | 1959 |

|

The Dätgen Man was found in 1959 near Dätgen, Germany. He had been stabbed, beaten, and decapitated. His severed head was found 3 metres (10 feet) from his body. He is not believed to have been sacrificed, but to have been killed and then mutilated, perhaps to prevent him from be coming a "wiedergänger", similar to a zombie.[55] His severed head displayed a Suebian knot. | |

| Esterweger Dose Child | Lower Saxony | 1164 CE | Undetermined | 1939 |

|

This completely skeletonized bog body of undetermined sex was either oversampled, lacked preservation or sustained damage during World War II. Surviving bones are marked red on image. | |

| Getelo bodies | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | One male and two females | 1857 | A man and two women discovered in Getelo, Germany[48] | ||

| Hesel bodies | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Female | 1914 | [48] | ||

| Hogenseth Man | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Male | 1920 | The Hogenseth Man was around 40–60 years old when he died. Because the body was left uncovered over night, the remains had been destroyed by townsfolk. Because of this, no carbon-14 dating could have been done.[56] | ||

| Hunteburg Foot | Lower Saxony | 1215–1300 CE | Undetermined | 1938 | The Hunteburg foot was found with a long shafted boot. | ||

| Hunteburg Men (Hunteburg I + II) | Grossenmoor Men | Lower Saxony | 245–450 CE | Male | 1949 | Two men were found buried in the same grave and wrapped in cloaks. Their bodies were lost during conservation. | |

| Hunteburg III | Lower Saxony | 40 BCE – 70 CE | Male | 1949 | Little is published about this find. | ||

| Husbäke I | Lower Saxony | 1000–300 BCE | Male | 1931 | This specimen had deteriorated so severely that it was destroyed during the 1950s. | ||

| Husbäke Man | Husbake II near Edewecht | Lower Saxony | 57–420 CE | Male | 1936 |

|

The man was found in 1936, lying face down in a bog in Ammerland, Germany. He had eaten fish before his death (in the Roman period) according to analysis of his intestines. He was around 20 to 25 years old at the time of his death.[57] His face was reconstructed to show what he may have looked like when he was alive.[58] |

| Johann Spieker | Jan Spieker | Lower Saxony | 1828 CE | Male | 1978 |

|

The preserved body of Johann Spieker was found in the Goldenstedter moor. Spieker was a hawker who had disappeared in the bog. The body was later reburied at the scene.[59] |

| Jührdenerfeld Man | Bockhornerfeld Man | Lower Saxony | 400 BCE-1 AD | Male | 1934 |

|

The body was discovered lying on its right side. Like the Windeby bodies, Dätgen man, and other bog bodies, some sticks were on top of him, probably to hold his body down. A piece of wool fabric and an animal skin cape were found on top of his body. He is currently on display at the Landesmuseum Natur und Mensch with the Husbäke man in Oldenburg, Germany.[60] |

| Kayhausen Boy | Lower Saxony | 300–400 BCE | Male | 1922 |

|

The boy is believed to have died between the ages of seven to ten years of age.[61] The boy had been bound and stabbed several times, on his throat and arm.[38][62] The child had an infected socket at the top of his femur and would not have been able to walk without assistance.[63] The boy's body is preserved in a formalin solution and is not displayed. | |

| Kreepen Man | Brammer Man[51] Kreepen-Brammer Man | Lower Saxony | 1440–1625 CE | Male | 1903 |

|

The body of a bearded man was found lying face down on 9 or 10 June 1903. No clothing was found on the body, although stones and twigs were nearby.[64] The remains were destroyed during World War II, but was dated after a piece of his hair was found. |

| Landegge Man | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Male | 1861 | [48] | ||

| Marx-Sapelstein Woman | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Female | 1861 | [48] | ||

| Neu England Man | Lower Saxony | 140–320 CE | Male | 1941 |

|

This man was believed to be from 40 to 50 years old when he died.[65] | |

| Neu Versen Man | "Roter Franz" | Lower Saxony | 220–430 CE | Male | 1900 |

|

The Neu Versen Man, also known as Roter Franz (meaning Red Franz in English), was discovered in 1900 in the Bourtanger Moor on the border of Germany and the Netherlands. The body dates to 220–430 CE of the Roman Iron Age.[66] The nickname of Red Franz derived from his red hair and beard. It was discovered that he was killed by having his throat slit, along with an arrow wound and a broken shoulder.[25][67] |

| Obenaltendorf Man | Lower Saxony | 380 CE | Male | 1895 |

|

Little remains of the body, but the clothing was preserved fairly well. Apart from clothing, a pair of silver burlocks were found.[68] | |

| Oberdorla Woman | Thuringia | Undetermined | Female | 1959–1964 | [45] | ||

| Osterby Man | Schleswig-Holstein | 70–220 CE[53] | Male | 1948 |

|

Osterby Man was discovered in a bog near Osterby, Germany, when two peat cutters were working. They unearthed the head two feet below the surface, wrapped in a roedeer skin cape. Scientists from the Archäologisches Landesmuseum Schleswig-Holstein estimated the man to have been around 50–60 years of age when he was killed. The man was decapitated; no other part of his body was ever found. His hair had probably been a light blond or gray color, but immersion in the bog had turned it red.[69] It is tied in the Suebian knot hairstyle, which the Roman historian Tacitus described as typical of free men of the Suebi tribe.[70] The head is mainly a skull, but there is still a small amount of skin on it.[71] The cause of the man's death was a blow to the left temple.[70] A 2007 re-examination showed that the jawbone did not belong on the skull.[69] | |

| Pangerfilze Man | Bavaria | 1700–1800 CE | Male | 1927 | No remains of the body have survived. This is because the body had possibly been destroyed during WWII. Little is published about this find. | ||

| Peiting Woman | "Rosalinde" | Bavaria | 1380–1440 CE | Female | 1957 | The corpse was found in a wooden coffin.[72] | |

| Possendorf body | Thuringia | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1959 | [45] | ||

| Rendswühren Man | Schleswig-Holstein | 50 CE | Male | 1871 |

|

The Rendswühren Man was discovered in 1871, at the Heidmoor Fen, near Kiel in Germany. He was examined by autopsy, which at the time was the only way of examination.[48]

Professor P.V. Glob wrote that Rendswühren Man was estimated to have been 40–50 years of age when he was battered to death, which left a triangular hole in his head. He was found naked, with a piece of leather on his left leg. A cape was found near him. After discovery, his corpse was smoked for preservation.[73] His skull had deteriorated, which required reconstruction.[74] Textile typologically the clothing found with the body has been dated into the Roman Iron Age of the 1st or 2nd century CE which has been confirmed by a carbon-14 dating of parts of the remains.[66] | |

| Rieper Moor body | Lower Saxony | 253–348 CE | Undetermined | 1751 | The bog body is no longer in existence; however, its clothing was successfully dated.[75] | ||

| Röst Girl | Schleswig-Holstein | 200 BCE – 80 CE | Female | 1926 |

|

The young girl was around three years old when she died with the initial cause of death unknown. The corpse was destroyed during the Second World War, which left only the cloak to scientifically date.[76] | |

| Rübke body | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1914 | [48] | ||

| Schalkholz body | Schleswig-Holstein | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1640 | First recorded bog body discovery[45] | ||

| Schwerinsdorf Man | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Male | 1961 | [48] | ||

| Sedelsberger boy | Sedelsberger Dose Man | Lower Saxony | 1040–1210 CE | Male | 1939 | The Sedelsberger Dose boy had been completely skeletonized. Prior to reexamination, the body was thought to be a woman from the age of 20–40 years old, but was later found to be a male under the age of sixteen.[1][48] | |

| Spelle bodies | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Two males, two females | 1921 | [48] | ||

| Sudmentzhausen body | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1881 | [48] | ||

| Girl of the Uchter Moor | "Moora" | Lower Saxony | 764–515 BCE | Female | 2000 |

|

The girl's preserved hand was discovered five years after her skeleton. Her skull was reconstructed from clay and digitally to show how she may have appeared in life. She was around 17–19 when she was deposited in the bog. Examination shows that she had been malnourished, had a curved spine, and had two skull fractures that had healed.[77] |

| Uphuser Klümoor Woman I | Lower Saxony | 27 BCE – 393 CE | Presumed Female | 1759 | The body wore a skirt and top holding bronze decorations, which were believed to be brooches, and without shoes. Her hair was plaited and a pot was found in her hand. In 1789, a similar find was discovered in the same bog. The Uphuser Klumoor Woman no longer remains.[78] | ||

| Uphuser Klümoor Woman II | Lower Saxony | Undetermined | Female | 1789 | [48] | ||

| Windeby I | Windeby Girl | Schleswig-Holstein | 41–118 CE | Male | 1952 |

|

One of the best preserved German bog bodies. Studies by Professor Heather Gill-Robinson show that the body was male. His reconstructed head is currently on display.[79] |

| Windeby II | Windeby Man | Schleswig-Holstein | 380–185 BCE | Male | 1952 | Found soon after Windeby I. The bones were decalcified and the clothes he may have worn had dissolved from being in the peat for so long. He had been strangled with a hazel rod which was wrapped around his neck.[80] |

Ireland

[edit]| Name | Other names | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballgudden Woman | Ulster | Undetermined | Female | 1831 | Examination showed that she had blond hair. Near her body, an infant of an undetermined sex was found. The remains of the baby were completely skeletonized. Both of these bog bodies no longer remain.[81][82] | ||

| Ballygroll Child | County Londonderry | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1835 | The child was discovered completely inside of a coffin, which is very uncommon for bog bodies. However, the body was either reburied, over sampled, or destroyed.[81] | ||

| Baronstown West Man | County Kildare[83] | 242–388 CE[84] | Male | 1953 |

|

This bog body is currently on display at the National Museum of Ireland. Hazel or birch branches were found with the body.[85] A textile and leather cloak were found on the body.[83] | |

| Bellaghy Boy | County Londonderry | ~300 BCE[86] | Male | 2023 | The remains, discovered in October 2023, consist of a headless skeleton, with partial skin, fingernails, toenails, and a kidney.[87] The remains were initially suspected to be a recent murder victim killed during the Troubles.[86] | ||

| Camnish Woman | County Londonderry | Undetermined | Female | 1834 | This bog body no longer remains. | ||

| Cashel Man | Portlaoise body | County Laois | 2000 BCE[9][88] | Male | 2011 | Because the body was in a crouched position, the body was believed to have dated from the Bronze Age. Radiocarbon dating supported this theory.[9] The body was later moved to the National Museum of Ireland for examination.[89][90][91][92][93] The man had a broken arm, along with having his back broken in two places and cut.[9][83] His skull and left arm were missing, being severed by the peat cutting machine, parts of them were later found.[94] Examination showed he was around 20–25 when he died.[9] A 2014 documentary suggested he may have been a former king.[9] | |

| Clonycavan Man | County Meath | 392–201 BCE | Male | 2003 |

|

Clonycavan Man was discovered three months before Old Croghan Man and was found in the same bog. Nothing remains below the waist of the man, either due to the turf cutting machine or when he had been brutally murdered. The body is famous for having a primitive form of gel found in his hair, which may have been imported from western Europe.[9] Like Cashel Man and Old Croughan Man, he was possibly once a king. His nipples and other body parts that consist of fragile tissue were missing, which could be from natural decomposition, or possibly mutilation; this has also led to at least one novel theory around the meanings of nipples.[95] | |

| Clonshannagh Woman | County Dublin | 645–680 CE | Female | 2005 | This bog body was found to be completely skeletonized. The body and its clothing had been partially dismembered by the peat cutting tools that had unearthed it.[96] | ||

| Derrycashel Woman[83] | County Roscommon | 1431–1291 BCE | Female | 2005 | The nearly skeletonized and complete remains of a young woman were unearthed.[96] It is believed that the cause of her death was not ritual sacrifice and that she was buried formally.[83] | ||

| Derrymaquirk Woman | County Roscommon | 750–200 BCE | Female | 1959 | The skeletonized woman was found lying on her back with bone fragments from an infant near her body. Examination showed that the age of the woman at the time of death was approximately 25. Pieces of wood and animal bones were also found in the grave.[97] It is thought that she had not been sacrificed but buried formally.[83] | ||

| Derryvarroge Man | County Kildare | 228–343 CE | Male | 2006 | The only parts of the man that remain preserved were the buttocks and leg of the body.[83][96] | ||

| Drumkeeragh body | County Down | Undetermined | Presumed Female | 1780 | The remains, consisting of a skeleton, clothing, and some hair, was found near Drumkeeragh Mountain by a peat-cutter.[98] A braided lock of hair from the body was given to Elizabeth Rawdon (or Lady Moira) in 1781, who took interest in the body and eventually published an article about the find in the Journal of Archaeologia. To this day, only the lock of hair and some cloth fragments remain.[99] | ||

| Gallagh Man | County Galway | 400–200 BCE | Male | 1821 |

|

The Gallagh Man was discovered lying on his side 275 cm (9 feet) below the surface of an Irish bog in 1821. A willow rod was found wrapped around his neck which was most likely used to strangle him. A cape was found around one of his lower legs.[83] The body was pinned to the bottom of the bog by two wooden pegs likely to keep it from surfacing. Analysis concluded that he was a young man at the approximate age of 25.[100] The body is on display in the National Museum of Ireland.[101] | |

| Kinakinelly Man | County Galway | 200–100 BCE | Male | 1952 | The man was found buried with bones of red deer.[83] | ||

| Meenybradden Woman | County Donegal | 1050–1410 CE | Female | 1978 | The woman was around 25–30 years old at her time of death. The Meenybradden woman's body has a 14C-date of 1050-1410 CE, but the cloak that her remains were wrapped in is of a style dated to the 16th–17th century, leading archaeologists to suggest that humic contamination may have affected the accuracy of the 14C-date.[102] Her body was buried about one meter deep in the bog. She was examined by John Harbison.[103] | ||

| Mulkeeragh Man | County Cork | Undetermined | Male | 1753 | This bog body was found wearing a military uniform and a cloak. The body was later reburied. | ||

| Old Croghan Man | Croghan Man | County Offaly | 362–175 BCE | Male | 2003 |

|

The Old Croughan Man was found in the same year as Clonycavan Man. Only the torso was discovered, lacking a head and abdomen. He was believed to have been 198 cm (6'6'') tall, and to have been a wealthy individual, since his hands lacked evidence of any hard labour.[9] Examination revealed that both Old Croughan Man and Clonycavan Man were in their twenties when they were killed and were of a high rank. Like Clonycavan Man, his nipples were also cut.[9][104] |

| Stoneyisland Man | Stony Island Man | County Galway | 3320–3220 BCE | Male | 1929 |

|

The skeletonized body was found by peat diggers and was originally believed to be the remains of a missing man. After examination the body was found to be over 5,000 years older. The cause of the man's death was probably drowning. He is known to be Ireland's oldest bog body.[105] |

Netherlands

[edit]| Name | Other names | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aschbroeken Man | Drenthe | 900 BCE | Male | 1931 |

|

The Aschbroeken Man's skull was lost soon after being unearthed. The remains consist of a skeleton, with an arm which healed abnormally. This may be the reason for his death, some other bog bodies from the Netherlands appear to have been killed for physical deformities.[106] | |

| Emmer-Erfscheidenveen Man | Drenthe | 1200 BCE | Male | 1938 |

|

The Emmer-Erfscheidenveen Man was a bog body recovered in Drenthe, Netherlands in 1938. The remains of the body itself were dated to approximately 1200 BCE, were poorly preserved.[107] although the body remains famous for the extent of preserved clothing which included a wool cap, deer skin shoes, a cow hide cape, and woolen undergarments.[108][109] Very little remains of this bog body; however, the clothing is exceptionally preserved. | |

| Exloërmond Man | Drenthe | 365–150 BCE | Male | 1914 |

|

The naked body of the Exloërmond Man was discovered on 15 May 1914 under 58 cm (1.9 feet) of the peat. There were no items found near the body at the location of discovery. Most of the right arm and left foot did not survive the 2000-some years in the bog. The front of the remains were not as well preserved as the back, which caused it to be hard to tell which sex the corpse was. After examination, remains of beard stubble was found on his face, which showed the body to be male. The reason and cause of his death are unknown.[110] | |

| Kibbelgaarn body | Drenthe | – | Male | 1791 | The body was discovered in the Bourtanger Moor, as well as the Neu-Versen Man and the Weerdinge Men. The skeletal remains were ground and used for mummia, which was a substance used for medicine in earlier times. No remains have survived today. | ||

| Weerdinge Men | Nieuw-Weerdinge Men, "Weerdinge Couple" | Drenthe | 160 BCE – 220 CE | Male | 1904 |

|

Two naked bog bodies were unearthed in the Bourtanger Moor. One of the two men is known to have had a large wound on his abdomen, with his intestines exposed. The two corpses were known as Weerdinge Couple and "Mr. & Mrs. Veenstra", because they were originally thought to be a man and a woman.[111] |

| Wijster bodies | "Wijster Four" | Drenthe | 1435–1625 CE | Male | 1901 | Four males were found. Examination showed that all four men had died before reaching the age of 25, one of whom was around 16 years old. They were found with clothing and other artifacts, such as coins. Only a partial skull fragment and one hand remain out of all four people.[106] | |

| Yde Girl | Drenthe | 54 BCE – 128 CE | Female | 1897 |

|

The girl was around 16 years old when she died. She is famous for being only 140 cm (4 feet 7 inches) tall when she was alive as well as having a curvature in her spine, which was caused by scoliosis. Her face was reconstructed in 1992 by forensic facial reconstruction artist Richard Neave.[112] | |

| Zweeloo Woman | Drenthe | 500 CE | Female | 1951 |

|

The body consists of the bones, internal organs and skin.[113] The woman had been placed into a large pit in the bog. She had lived with dyschondrosteosis, causing short forearms and legs. Other signs of sickness found were round worms and whipworm, although the cause of death is unknown. It is thought that she was around 35 years old when she died.[114] |

Poland

[edit]| Name | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dąbrówka body | Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1936 | ||

| Dröbnitz Girl | Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship | 650 BCE | Female | 1939 |

|

Examination of the intestines and stomach contents showed that before her death the girl had eaten foods such as gruel and several types of vegetables. Further pollen analysis indicated that she had died during the spring months. A cloak and wooden comb were found with the body. Her body, as well as her grave goods, no longer remain due to their destruction during World War II.[97][115] |

| Karwinden Man | Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship | Undetermined | Male | 1943 | [45] |

Sweden

[edit]| Name | Other names | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bocksten Man | Bockstensmannen | Varberg, Hallands län | 1290–1430 CE | Male | 1936 |

|

Bocksten Man was violently beaten to death[116] at the approximate age of 25–60 years of age. The corpse is famous for having one of the most complete surviving set of garments from the 14th century. A theory suggests that the identity of the Bocksten Man have been the dean of the Diocese of Linköping.[117] |

| Luttra Woman | "Hallonflickan" Raspberry Girl |

Västra Götalands län | 3105–2935 BCE | Female | 1943 |

|

Because there were very many raspberry seeds found around the stomach area, the body was dubbed "Hallonflickan" (meaning "Raspberry Girl" in English). She was 20–25 years old when she had died. The cause of her death remains a mystery; however, a flint arrowhead was found near to where the body was discovered three years before. She was probably buried in open water, due to the evidence of aquatic snails. The soft tissues of the body had not survived, resulting in skeletonization.[118][119] |

Great Britain

[edit]| Name | Other names | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amcotts Moor Woman | Lincolnshire, England | 200–400 CE | Female | 1747 | The Amcotts Moor Woman was discovered when the discoverer had dug six feet into the bog, his shovel struck a shoe. The man began to uncover a human foot, and he fled the scene. The body was later completely uncovered by George Stovin, who was a doctor, and his assistants.[120] Most of the foot had gone through skeletonization; however, the heel had been preserved. Some skin of the lower body and arms were unearthed, along with hair and fingernails. Today, only her left shoe has survived.[121][122] | ||

| Grewelthorphe remains | Yorkshire, England | Undetermined | Undetermined | 1850 | This bog body was described to have been wearing brightly coloured clothing when it was unearthed. The body was then taken to a church graveyard and was buried. However, fragments of the shoes had been removed from the corpse by a police man and are all that remain of the body.[81] | ||

| Gunnister Man | Gunnister, Scotland | 18th century | Male | 1951 | This bog body was found accompanied by a complete set of garments, containing the earliest examples of knitted fabric in Shetland. The remains are held at National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.[123] | ||

| Lindow Woman | Lindow I | Cheshire, England | 250 CE | Female | 1983 | The skull fragment was originally thought to be the deceased wife of Peter Reyn-Bardt, who confessed to her murder after the discovery. But after the skull was dated, it was proven to be much older than Mrs. Reyn-Bardt. Peter Reyn-Bardt was convicted for his wife's murder anyway.[124][125] | |

| Lindow Man | Lindow II "Pete Marsh" | Cheshire, England | 2 BCE-119 CE | Male | 1984 |

|

Examination revealed that the man was in his mid twenties. His official name is Lindow II, though he was nicknamed "Pete Marsh" by journalists. The man's injuries were a blunt force trauma wound to the head which left a small hole, a stab wound to the chest as well as a possible stab to his neck. There was also a cord found around his neck, thought to be a garrote or a necklace.[126] The skull was reconstructed by Richard Neave, who is also known for his work on Yde Girl. A theory states that the partial remains of Lindow IV found in 1988 are part of Lindow Man.[127]: 18 |

| Lindow III | Cheshire, England | Early Iron Age | Male | 1987 | The body was severed into over seventy pieces by the turf cutting machine.[128] The tissue, however, was in good condition.[128] | ||

| Prestatyn Child | Clwyd, Wales | 90 CE | Undetermined | 1984 | The corpse was believed to be that of an infant. Little is published about this find.[129] | ||

| Worsley Man | Manchester, England | 131-251 CE | Male | 1958 | The Worsley man had been garroted and beheaded. He was around 26–45 years of age when he was killed, most likely by ritual sacrifice. The garrote was found still around the man's neck.[130] | ||

| Cladh Hallan Skeletons | South Uist, Scotland | 1600–1120 BCE[131] | Males and Females | 1988–2002 |

|

Remains of several prehistoric human skeletons are described in Pearson, Michael Parker; Sharples, Niall M.; Symonds, James (2004). South Uist: Archaeology and History of a Hebridean Island. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2905-2. The image shows a diagram of a skeleton containing the bones of three different people. Some of the skeletons were compiled of six different people.[132] |

Other locations

[edit]| Name | Location | Age (carbon-14 dating) | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleivik Man | Rogaland, Norway | 6110–5890 BCE | Male | 1952 | The man was discovered by a farmer who had discovered a bone 70 centimeters deep inside of a drainage ditch. Examination revealed that the man was approximately 55–60 at the time of his death. The cause of the man's demise remains a mystery because of the few body parts that were found, which include the skull, teeth, one rib bone and two vertebra.[133][134] | |

| Windover Skeletons | Florida, United States | 6000–5000 BCE | Males and females | 1982 | 168 skeletons found in soft peat, ages range from infants to elderly. Some skeletons bore wounds that may have caused death.[135][136][137] DNA was extracted from preserved brain tissue.[138] | |

| Little Salt Spring skeletons | Florida, United States | 3200–4800 BCE | Males and females | Before 1979 | Hundreds of skeletons were found in soft peat. Some of the skulls held preserved brain matter.[139] | |

| Rabivere Woman | Rabivere, Estonia | ~1667 | Female | 1936 | The woman was discovered by peat diggers. Some clothes were well preserved and revealed that she was wearing two jackets, a woollen skirt and gloves. On her chest under her clothes was a brooch, near her hand was a coin dating to 1667. It is suspected she was a murder or hanging victim, due to wounds on her neck.[140] |

See also

[edit]- Egtved Girl, a barrow body in a coffin preserved by a bog

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Gill-Robinson, Heather (2005). The Iron Age Bog Bodies of the Archäologische Landesmuseum Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig, Germany.

- ^ van der Sanden, Wijnand; Eisenbess, Sabine (2006). "Imaginary People". Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt. 36 (1): 111–122. ISSN 0342-734X.

- ^ Lange, Karen E. (September 2007). "Tales From the Bog". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008.

- ^ Gill-Robinson, Heather (2005). The Iron Age Bog Bodies of the Archäologische Landesmuseum Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig, Germany. p. 48.

- ^ a b c Glob, Peter V. The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved. Trans. Rupert Bruce-Mitford. Ithaca, New York: Faber and Faber Limited, 1969. 82–100. Print.

- ^ Den Blauwen Swaen. "Bog Bodies from Scandinavia". Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ a b Deem, James M. "Borremose Man". Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lauber, Patricia G. (1985). Tales Mummies Tell. HarperCollins. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-690-04389-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hart, Edward, dir. "Ghosts of Murdered Kings." NOVA. Prod. Edward Hart and Dan McCabe. PBS. 29 Jan. 2014. Television.

- ^ a b c Gill-Robinson, Heather (2005). The Iron Age Bog Bodies of the Archäologische Landesmuseum Schloss Gottorf. pp. 64–65.

- ^ Borremose Woman Archived 23 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Vandkilde, Helle (2003), "Tollund Man", in Bogucki, Crabtree (ed.), Ancient Europe 8000 B.C. – A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World, vol. 1, London: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 27

- ^ a b Gill-Robinson, Heather (2005). The Iron Age Bog Bodies of the Archäologische Landesmuseum Schloss Gottorf. p. 63.

- ^ a b Silkeborg Museum (2004). "Elling Woman". Denmark. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Glob, Peter V. The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved. Trans. Rupert Bruce-Mitford. Ithaca, New York: Faber and Faber Limited, 1969. 80–82. Print.

- ^ Lynnerup, Niels (22 May 2015). "Bog Bodies: BOG BODIES". The Anatomical Record. 298 (6): 1007–1012. doi:10.1002/ar.23138. PMID 25998635.

- ^ Archaeology Magazine – Bodies of the Bogs – Pathologies of the Bog Bodies. Archaeology.org. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ "Pathologies of the Bog Bodies". Archaeology Magazine. N.p. 1997. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Grauballe". Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Archaeological Institute "Haraldskaer Woman: Bodies of the Bogs", Archaeology, Archaeological Institute of America, 10 December 1997.

- ^ Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. (2006). Boudica Britannia. Pearson Education. pp. 95–96. ISBN 1-4058-1100-5.

- ^ "The woman from Huldremose" Archived 28 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Meet Danish Prehistory, Nationalmuseet, retrieved 3 February 2010

- ^ "How did the Huldremose woman die?" Archived 30 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Meet Danish Prehistory, Nationalmuseet, retrieved 3 February 2010

- ^ Frabetti, P.L.; Cheung, H.W.K.; Cumalat, J.P.; Dallapiccola, C.; Ginkel, J.F.; Johns, W.E.; Nehring, M.S.; Vaandering, E.W.; Butler, J.N.; Cihangir, S.; Gaines, I.; Garbincius, P.H.; Garren, L.; Gourlay, S.A.; Harding, D.J.; Kasper, P.; Kreymer, A.; Lebrun, P.; Shukla, S.; Vittone, M.; Baldini-Ferroli, R.; Benussi, L.; Bertani, M.; Bianco, S.; Fabbri, F.L.; Pacetti, S.; Zallo, A.; Cawlfield, C.; Culbertson, R.; et al. (2004), "On the narrow dip structure at 1.9 GeV/c2 in diffractive photoproduction" (PDF), Physics Letters B (in German), 578 (3–4): 290–296, Bibcode:2004PhLB..578..290F, doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2003.10.071, S2CID 38847591

- ^ a b Bog Bodies – Photo Gallery – National Geographic Magazine. Ngm.nationalgeographic.com (17 October 2002). Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Frederiksdalmanden. Frederiksdal-info.dk. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Archaeology Magazine – Bodies of the Bogs – Koelbjerg Woman. Archaeology.org. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Pedersen, K.L. (2 April 2017). Ny DNA-forskning: Danmarks ældste lig skifter køn fra kvinde til mand. DR Nyheder. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ a b Weapons, violence and death in the Neolithic period – Oldtiden Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Oldtiden.natmus.dk. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity.

- ^ a b Munksgaard, Elizabeth (1984). "Bog bodies- a brief summary of inerpretations". Journal of Danish Archaeology. 3: 121. doi:10.1080/0108464X.1984.10589917.

- ^ Gill-Robinson, Heather (2005). The Iron Age Bog Bodies of the Archäologische Landesmuseum Schloss Gottorf. p. 298.

- ^ "Human sacrifice in the early Neolithic period – Oldtiden". Oldtiden.natmus.dk. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ "Pathologies of the bog bodies". Archaeology Magazine. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through nature to eternity: the bog bodies of northwest Europe. Amsterdam: Batavian Lion International. p. 125,194. ISBN 90-6707-418-7.

- ^ Archaeology Magazine – Bodies of the Bogs – Clothing and Hair Styles. Archaeology.org. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ "Pathologies of the Bog Bodies". Archaeology Magazine. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Violence in the Bogs". Archaeology.org. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Peter Vilhelm Glob (2004). The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved. New York Review Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-59017-090-8.

- ^ Mummytombs.com Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ "The Tollund Man – The Naked Body". Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ Borderland-stalkers and Stalking Horses. Horse Sacrifice as Liminal Activity in the Early Iron Age. (Anne Monikander) – Academia.edu

- ^ Anderson, S. Ry; Geertinger, Preben (1984). "Bog bodies Investigated in the Light of Forensic Medicine". Journal of Danish Archaeology. 3: 115.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (15 February 2024). "'Vittrup Man' violently died in a bog 5,200 years ago. Now, researchers know his story". CNN. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. p. 193.

- ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. p. 91.

- ^ Moorleiche. Landesmuseum-emden.de. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. Batavian Lion International. pp. 48, 192.

- ^ Arnold, Heinke; Drews, Erika (2006). Die so genannte Halsschnur von Bunsoh (PDF). Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa Bilanz 2007 (5 ed.). Oldenburg: Isensee Verlag. pp. 135–443. ISBN 978-3-89995-447-0. Retrieved 4 May 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Rosendahl, Wilfried, Markus Bertling, and Heather Gill-Frerking. "The Bog Dog From Burlage." Mummies of the World. Ed. Alfried Wieczorek and Wilfried Rosendahl. First ed. 2009. 298-99. Print.

- ^ a b c "Dating bog bodies by means of 14C-AMS" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Damendorf Man Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ a b Archaeology Magazine – Bodies of the Bogs – Clothing and Hair Styles. Archaeology.org. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. p. 104.

- ^ Datgen Man Archived 3 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Hajo Hayen: Die Moorleiche aus Hogenseth 1920. In: Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Nordwestdeutschland. 2, 1979, ISSN 0170-5776, S. 46–48.

- ^ Husbake Man Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Paleopathology, forensics and reconstruction of the bog bodies from Northern Germany Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Research-projects.uzh.ch. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Vergano, Dan (16 January 2011). "Bog bodies baffle scientists". USA Today. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Bockhornerfeld Man Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Archaeology.about.com. Archaeology.about.com (4 August 2010). Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Madea, Burkhard, Johanna Preuss, and Frank Musshoff. "From Flourishing Life to Dust-The Natural Cycle." Mummies of the World. Ed. Alfried Wieczorek and Wilfried Rosendahl. First ed. 2010. 28. Print

- ^ WAC6.org

- ^ van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. Batavian Lion International. p. 89.

- ^ Neu England Man Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ a b Van Der Plicht, J.; Van Der Sanden, W. A. B.; Aerts, A. T.; Streurman, H. J. (2004), "Dating bog bodies by means of 14C-AMS", Journal of Archaeological Science, 31 (4): 471–491, Bibcode:2004JArSc..31..471V, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.520.411, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2003.09.012

- ^ "Violence in the Bogs ", Bodies of the Bogs, Archaeological Institute of America, 10 December 1997

- ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. p. 94.

- ^ a b "Osterby Man". Mummytombs.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ a b PBS.org. PBS.org. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Deem, James M. (1998). Bodies from the Bog. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-395-85784-7.

- ^ Haas-Gebhard, Brigitte; Püschel, Klaus (2009), Die Frau aus dem Moor – Teil 1, Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter (in German), vol. 74, Beck, pp. 239–268, ISBN 978-3-406-11079-5, ISSN 0341-3918 – via Kommission für Bayerische Landesgeschichte

- ^ Deem, James M. "Landesmuseum at the Schloß Gottorf in Schleswig, Germany". Mummytombs.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Gill-Frerking, Heather. "Bog Bodies-Preserved form Peat." Mummies of the World. Ed. Alfried Wieczorek and Wilfried Rosendahl. 2010. 64-6. Print.

- ^ Hesse, Stefan; Grefen-Peters, Silke; Peek, Christina; Rech, Jennifer; Schliemann, Ulrich (2010). Die Moorleichen im Landkreis Rotenburg (Wümme) Forschungsgeschichte und neue Untersuchungen [The Bog Bodies in the District of Rotenburg (Wümme). Research History and New Investigations.]. Archäologische Berichte des Landkreises Rotenburg (Wümme) (in German). Vol. 16.

- ^ van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. p. 82.

- ^ "Identify the remains of Iron Age woman". All Voices. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. Batavian Lion International. pp. 69, 192.

- ^ Deem, James M. "Windeby I". Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Bog bodies from Germany and Poland". denblauwenswaen.nl. 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ a b c "Bogbodies from the United Kingdom & Ireland". denblauwenswaen.nl. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ Magan, M. (2022) Listen to the Land Speak: A Journey into the Wisdom of What Lies Beneath Us, Gill and MacMillan, Chapter: Bog Bodies

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kelly, Eamonn P. (10 January 2012). "Irish Iron Age Bog Bodies". Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "The Peat Men from Clonycavan and Oldcroghan". British Archaeology (110). 2010.

- ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). From Nature to Eternity. p. 99.

- ^ a b Watkins, Ali (29 February 2024). "In Ancient Bones, a Reminder That Northern Ireland's Ghosts Are Never Far". The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Bog body from 2,500 years ago discovered in N. Ireland". Reuters. 25 January 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Laois Bog Body Said to be the World's Oldest". The Irish Times.

- ^ "Morning Ireland: Bog body to be removed to the National Museum – Audio – RTÉ News Player". RTÉ.ie. 12 August 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ Hobbies « Citizen's Free Press Ireland: News Line[permanent dead link]

- ^ Lostchildreninthewilderness.wordpress.com

- ^ Hilts, Carly (4 October 2011). "Uncovering the secrets of Cashel Man". Current Archaeology. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ "Irish bog bodies, some recent discoveries | Irish Archaeology". Irisharchaeology.ie. 11 August 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ "NOVA | Ghosts of Murdered Kings". Pbs.org. 13 August 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Sanz, Catherine. "Google offended by the naked truth".

- ^ a b c "Feature: British Archaeology 110, January / February 2010". Britarch.ac.uk. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ a b Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). From Nature to Eternity. p. 96.

- ^ Moira, Elizabeth, Countess of (1785). "Particulars relative to a Human Skeleton, and the Garments that were found thereon, when dug out of a Bog at the Foot of Drumkeragh, a Mountain in the County of Down, and Barony of Kinalearty, on Lord Moira's Estate, in the Autumn of 1780. In a Letter to the Hon. John Theophilus Rawdon, by the Countess of Moira; communicated by Mr. Barrington". Archaeologia. 7: 90–110. doi:10.1017/S0261340900022281. ISSN 0261-3409.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. Batavian Lion International. pp. 46–48, 200. ISBN 978-90-6707-418-6.

- ^ NOVA (2006). "The Perfect Corpse". WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Gallagh Man Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Delaney M, Ó Floinn R (1995). "A Bog Body from Meenybraddan Bog, County Donegal, Ireland". In Turner RC, Scaife RG (eds.). Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives. London: British Museum Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780714123059.

- ^ Irish Peatland Conservation Council – information sheets – Bog Bodies Archived 26 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Ipcc.ie. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Owen, James (17 January 2006). "Murdered 'Bog Men' Found With Hair Gel, Manicured Nails". London, England: National Geographic. p. 1. Archived from the original on 27 January 2006. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Cowell, John Joe (1998). Lickmolassy by the Shannon:A History of Gortanumera & Surrounding Parishes. John Joe Conwell. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-9534776-0-9.

- ^ a b "Bogbodies of the Netherlands". denblauwenswaen.nl. 29 June 1904. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ D. Sivrev, et al, Modern Day Plastination Techniques – Successor of Ancient Embalming Methods[permanent dead link], Trakia Journal of Sciences, 2005, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp 48–51

- ^ "Clothing and Hair Styles of the Bog People ", "Bodies of the Bogs, Archaeological Institute of America, 10 December 1997

- ^ Featured Netherlands Mummy Museums: Drents Museum in Assen: Emmer-Erscheidenveen Man Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Mummytombs.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Van Vilsteren, Vincent T. "Bodies Buried in Bogs-The Drents Museum in Assen, the Netherlands." Mummies of the World. Ed. Alfried Wieczorek and Wilfried Rosendahl. 2010. 300-01. Print.

- ^ Deem, James. "Weerdinge Men". Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Neave, Richard; Smith, Denise. "The Yde Girl". RN-DS Partnership. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ List of Contents: Bodies from the Bog by James M. Deem Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Jamesmdeem.com. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Wieczorek, Alfried; Rosendahl, Wilfried (2010). Gill-Frerking, Heather (ed.). Mummies of the World. New York, NY United States: Prestel Publishing Ltd. pp. 301, 302. ISBN 978-3-7913-5030-1.

- ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity: The Bog Bodies of Northwest Europe. Batavian Lion International. p. 111. ISBN 978-90-6707-418-6.

- ^ Larsson, Micke; Olander, Karin (23 January 2006). "Bockstensmannen blev mördad" (in Swedish). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Wem Var Bockstenmannen?". Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Gejvall, N. G.; Hjortsjö, C. H.; Sahlström, K. E. Stenålderskvinnan från Luttra i svensk antropologisk belysning (in Swedish). p. 417.

- ^ Ahlström, Torbjörn; Sten, Sabine. Hallonflickan (in Swedish). Curry Heimann. pp. 22–25.

- ^ Waller, Symeon. "Bog Body in Doncaster". Doncaster History. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Turner, R.C., and M Rhodes. "A bog body and its shoes from Amcotts Lincolnshiere." Antiquaries Journal 72 (1992): 1–3. Web. 11 October 2011.

- ^ NOVA | The Perfect Corpse | Bog Bodies of the Iron Age (non-Flash). PBS. Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Henshall, Audrey S.; Maxwell, Stuart (1951–1952). "Clothing and Other Articles from a Late 17th-century grave at Gunnister, Shetland" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 86: 30–42. doi:10.9750/PSAS.086.30.42.

- ^ "Ancient Skull Leads Man to Confess to Wife's Murder". The Courier. 14 December 1983. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Sammut, Dave; Craig, Chantelle (23 July 2019). "Bodies in the Bog: The Lindow Mysteries". Distillations. Science History Institute. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Joy, Jody (2009), Lindow Man, British Museum Press, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-7141-2817-7

- ^ Turner, Rick C. (1995), "Discoveries and Excavations at Lindow Moss 1983–8", Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives, British Museum Press, pp. 10–18, ISBN 0-7141-2305-6

- ^ a b Turner 1995, pp. 13–14

- ^ Van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity. p. 100.

- ^ Giles, Melanie (2020). Bog bodies: Face to face with the past. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 217–248. ISBN 978-1-5261-5018-9.

- ^ "The Prehistoric Village at Cladh Hallan". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 21 Feb 2008.

- ^ Kaufman, Rachel (6 July 2012). "'Frankenstein' Bog Mummies Discovered in Scotland". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ van der Sanden, Wijnand (1996). Through Nature to Eternity – The Bog Bodies of Northwest Europe. Amsterdam: Batavian Lion International. pp. 85, 177. ISBN 978-90-6707-418-6.

- ^ Gisle Bang. The Age of a Stone Age human skeleton Determined by Means of root dentin Tranparencey in: Norwegian Archaeological Review. No. 26, 1993, p. 55-57.

- ^ Milanich, Jerald (1994). Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8130-1273-5.

- ^ Brown, Robin (1994). Florida's First People: 12,000 Years of Human History. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. pp. 21–22, 24. ISBN 978-1-56164-032-4.

- ^ Richardson, Joseph. "The Windover Archaeological Research Project". North Brevard Business Directory. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ Brown, Robin (1994). Florida's First People: 12,000 Years of Human History. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. pp. 22, 25. ISBN 978-1-56164-032-4.

- ^ Purdy, Barbara A. (2008). Florida's People During the Last Ice Age. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 84–90. ISBN 978-0-8130-3204-7.

- ^ Kama, Pikne; Rammo, Riina (2015). Rabivere soost leitud mumifitseerunud naise surnukeha: õnnetusjuhtum, mõrv või traditsiooniline käitumine?. Tartu: Tutulus, Tartu University. pp. 10, 11.