Banksy

Banksy | |

|---|---|

Banksy art on Brick Lane, East End of London, 2004 | |

| Born | |

| Known for | Street art |

| Website | |

Banksy is a pseudonymous England-based street artist, political activist, and film director whose real name and identity remain unconfirmed and the subject of speculation.[2] Active since the 1990s, his satirical street art and subversive epigrams combine dark humour with graffiti executed in a distinctive stenciling technique. His works of political and social commentary have appeared on streets, walls, and bridges throughout the world.[3] His work grew out of the Bristol underground scene, which involved collaborations between artists and musicians.[4] Banksy says that he was inspired by 3D, a graffiti artist and founding member of the musical group Massive Attack.[5]

Banksy displays his art on publicly visible surfaces such as walls and self-built physical prop pieces. He no longer sells photographs or reproductions of his street graffiti, but his public "installations" are regularly resold, often even by removing the wall on which they were painted.[6] Much of his work can be classified as temporary art.[7] A small number of his works are officially, non-publicly, sold through an agency he created called Pest Control.[8] Banksy's documentary film Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010) made its debut at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival.[9] In January 2011, he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature for the film.[10] In 2014, he was awarded Person of the Year at the 2014 Webby Awards.[11]

Identity

Banksy's name and identity remain unconfirmed and the subject of speculation. In a 2003 interview with Simon Hattenstone of The Guardian, Banksy is described as "white, 28, scruffy casual—jeans, T-shirt, a silver tooth, silver chain and silver earring. He looks like a cross between Jimmy Nail and Mike Skinner of The Streets."[12] An ITV News segment of 2003 featured a short interview with someone identified in the reporting as Banksy.[13] Banksy began as an artist at the age of 14, was expelled from school, and served time in prison for petty crime. According to Hattenstone, "anonymity is vital to him because graffiti is illegal".[12] Banksy reportedly lived in Easton, Bristol, during the late 1990s, before moving to London around 2000.[14][15][16]

The Mail on Sunday claimed in 2008 that Banksy is Robin Gunningham,[17] born on 28 July 1974 in Yate, 12 miles (19 km) from Bristol.[18][19][14] Several of Gunningham's associates and former schoolmates at Bristol Cathedral School have corroborated this, and, in 2016, a study by researchers at the Queen Mary University of London using geographic profiling found that the incidence of Banksy's works correlated with the known movements of Gunningham.[20][21][22][23] According to The Sunday Times, Gunningham began employing the name Robin Banks, which eventually became Banksy. Two cassette sleeves featuring his art work from 1993, for the Bristol band Mother Samosa, exist with his signature.[24] In June 2017, DJ Goldie referred to Banksy as "Rob" in an interview for a podcast.[25] In an interview with the BBC in 2003, which was rediscovered in November 2023, reporter Nigel Wrench asked if Banksy is called Robert Banks; Banksy responded that his forename is Robbie.[26]

Other alternate speculations on Banksy's identity include the following:

- Robert Del Naja (also known as 3D), a member of the trip hop band Massive Attack, had been a graffiti artist during the 1980s prior to forming the band, and was previously identified as a personal friend of Banksy.[27][28]

- In 2020, users on Twitter began to speculate that former Art Attack presenter Neil Buchanan was Banksy. This was denied by Buchanan's publicist.[29]

- In 2022, Billy Gannon, a local councillor in Pembroke Dock was rumoured to be Banksy. He resigned because the speculation was affecting his ability to carry out the duties of a councillor. "I'm being asked to prove who I am not, and the person that I am not may not exist," he said. "I mean, how am I supposed to prove that I'm not somebody who doesn't exist? Just how do you do that?"[30]

In October 2014, an internet hoax circulated that Banksy had been arrested and his identity revealed.[31]

Career

Early career (1990–2001)

Banksy started as a freehand graffiti artist in 1990–1994[33] as one of Bristol's DryBreadZ Crew (DBZ), with two other artists known as Kato and Tes.[34] He was inspired by local artists and his work was part of the larger Bristol underground scene with Nick Walker, Inkie and 3D.[35][36] During this time he met Bristol photographer Steve Lazarides, who began selling Banksy's work, later becoming his agent.[37] By 2000 he had turned to the art of stencilling after realising how much less time it took to complete a work. He claims he changed to stencilling while hiding from the police under a rubbish lorry, when he noticed the stencilled serial number[38] and by employing this technique, he soon became more widely noticed for his art around Bristol and London.[38] He was the goalkeeper for the Easton Cowboys and Cowgirls football team in the 1990s, and toured with the club to Mexico in 2001.[39] Banksy's first known large wall mural was The Mild Mild West painted in 1997 to cover advertising of a former solicitors' office on Stokes Croft in Bristol. It depicts a teddy bear lobbing a Molotov cocktail at three riot police.[40]

Banksy's stencils feature striking and humorous images occasionally combined with slogans. The message is usually anti-war, anti-capitalist, or anti-establishment. Subjects often include rats, apes, policemen, soldiers, children, and the elderly.[citation needed]

Exhibitions (2002–2003)

On 19 July 2002, Banksy's first Los Angeles exhibition debuted at 331⁄3 Gallery, a tiny Silver Lake venue owned by Frank Sosa and was on view until 18 August.[41][42] The exhibition, entitled Existencilism, "an Exhibition of Art, Lies and Deviousness" was curated by 331⁄3 Gallery, Malathion LA's Chris Vargas, Funk Lazy Promotions' Grace Jehan, and B+.[43] The flyer of the exhibition indicates an opening reception was followed by a performance by Money Mark with DJ's Jun, AL Jackson, Rhettmatic, J.Rocc, and Coleman.[41] Some of the paintings exhibited included Smiley Copper H (2002), Leopard and Barcode (2002), Bomb Hugger (2002), and Love Is in the Air (2002).[42][44]

In 2003, at an exhibition called Turf War, held in a London warehouse, Banksy painted on animals. At the time he gave one of his very few interviews, to the BBC's Nigel Wrench.[45] Although the RSPCA declared the conditions suitable, an animal rights activist chained herself to the railings in protest.[46] An example of his subverted paintings is Monet's Water Lily Pond, adapted to include urban detritus such as litter and a shopping trolley floating in its reflective waters; another is Edward Hopper's Nighthawks, redrawn to show that the characters are looking at a British football hooligan, dressed only in his Union Flag underpants, who has just thrown an object through the glass window of the café. These oil paintings were shown at a twelve-day exhibition in Westbourne Grove, London in 2005.[47]

Banksy, along with Shepard Fairey, Dmote, and others, created work at a warehouse exhibition in Alexandria, Sydney, for Semi-Permanent in 2003. Approximately 1,500 people attended.

£10 notes to Barely Legal (2004–2006)

In August 2004, Banksy produced a quantity of spoof British £10 notes[48] replacing the picture of the Queen's head with Diana, Princess of Wales's head and changing the text "Bank of England" to "Banksy of England". Someone threw a large wad of these into a crowd at Notting Hill Carnival that year, which some recipients then tried to spend in local shops. These notes were also given with invitations to a Santa's Ghetto exhibition by Pictures on Walls. The individual notes have since been selling on eBay. A wad of the notes was also thrown over a fence and into the crowd near the NME signing tent at the Reading Festival. A limited run of 50 signed posters containing ten uncut notes was also produced and sold by Pictures on Walls for £100 each to commemorate the death of Princess Diana. One of these sold in October 2007 at Bonhams auction house in London for £24,000.[49]

The reproduction of images of the banknotes classifies as a criminal offence (s.18 Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981). In 2016, the American Numismatic Society received an email from a Reproductions Officer at the Bank of England, which brought attention to the illegality of publishing photos of the banknotes on their website without prior permission.[50] The Bank of England holds the copyright over all its banknotes.[51]

Also in 2004, Banksy created a limited edition screenprint titled Napalm (Can't Beat That Feeling). In the print, Banksy appropriated the image of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, a Vietnamese girl who appeared in the iconic 1972 photograph "The Terror of War" by Nick Ut. Napalm shows the image of Kim Phuc as seen in the original photo, but no longer within the tragic war setting. Instead, he situates the young girl against an empty background, still screaming, but now accompanied by Ronald McDonald and Mickey Mouse. The two characters hold her hands as they cheerfully gesture to an invisible audience, seemingly oblivious to the terrified girl. The image of Kim Phuc is flat, grainy and monochromatic; in most of the prints, Ronald McDonald and Mickey Mouse are yellow. In a few limited prints, the corporate characters wear pink or orange. Banksy produced 150 signed and 500 unsigned copies of Napalm.[52][53][54]

In August 2005, Banksy, on a trip to the Palestinian territories, created nine images on the Israeli West Bank wall.[55]

There are crimes that become innocent and even glorious through their splendour, number and excess.

Banksy held an exhibition called Barely Legal, billed as a "three-day vandalised warehouse extravaganza" in Los Angeles, on the weekend of 16 September 2006. The exhibition featured a live "elephant in a room", painted in a pink and gold floral wallpaper pattern, which, according to leaflets handed out at the exhibition, was intended to draw attention to the issue of world poverty. Although the Animal Services Department had issued a permit for the elephant, after complaints from animal rights activists, the elephant appeared unpainted on the final day. Its owners rejected claims of mistreatment and said that the elephant had done "many, many movies. She's used to makeup."[57] Banksy also made artwork displaying Queen Victoria as a lesbian and satirical pieces that incorporated art made by Andy Warhol and Leonardo da Vinci.[58]

Peter Gibson, a spokesman for Keep Britain Tidy, asserts that Banksy's work is simple vandalism.[59] Another official for the same organisation stated: "We are concerned that Banksy's street art glorifies what is essentially vandalism."[60]

Banksy effect (2006–2007)

After Christina Aguilera bought an original of Queen Victoria as a lesbian and two prints for £25,000,[62] on 19 October 2006, a set of Kate Moss paintings sold in Sotheby's London for £50,400, setting an auction record for Banksy's work. The six silk-screen prints, featuring the model painted in the style of Andy Warhol's Marilyn Monroe pictures, sold for five times their estimated price. Their stencil of a green Mona Lisa with real paint dripping from her eyes sold for £57,600 at the same auction.[63] In December, journalist Max Foster coined the phrase, "the Banksy effect", to illustrate how interest in other street artists was growing on the back of Banksy's success.[64]

On 21 February 2007, Sotheby's auction house in London auctioned three works, reaching the highest ever price for a Banksy work at auction: over £102,000 for Bombing Middle England. Two of his other graffiti works, Girl with Balloon and Bomb Hugger, sold for £37,200 and £31,200 respectively, which were well above their estimated prices.[65] The following day's auction saw a further three Banksy works reach soaring prices: Ballerina with Action Man Parts reached £96,000; Glory sold for £72,000; Untitled (2004) sold for £33,600; all significantly above price estimates.[66] To coincide with the second day of auctions, Banksy updated his website with a new image of an auction house scene showing people bidding on a picture that said, "I Can't Believe You Morons Actually Buy This Shit."[60]

In February 2007, the owners of a house with a Banksy mural on the side in Bristol decided to sell the house through Red Propeller art gallery after offers fell through because the prospective buyers wanted to remove the mural. It is listed as a mural that comes with a house attached.[67]

In April 2007, Transport for London painted over Banksy's image of a scene from Quentin Tarantino's film Pulp Fiction (1994), featuring Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta clutching bananas instead of guns. Although the image was very popular, Transport for London claimed that the graffiti created "a general atmosphere of neglect and social decay which in turn encourages crime" and their staff are "professional cleaners not professional art critics".[68] Banksy painted the same site again and, initially, the actors were portrayed as holding real guns instead of bananas, but they were adorned with banana costumes. Sometime later, Banksy made a tribute artwork over this second Pulp Fiction work. The tribute was for 19-year-old British graffiti artist Ozone who, along with fellow artist Wants, was hit by an underground train in Barking, east London on 12 January 2007.[69] Banksy depicted an angel wearing a bullet-proof vest holding a skull. He also wrote a note on his website saying:

The last time I hit this spot I painted a crap picture of two men in banana costumes waving handguns. A few weeks later a writer called Ozone completely dogged it and then wrote "If it's better next time I'll leave it" in the bottom corner. When we lost Ozone we lost a fearless graffiti writer and as it turns out a pretty perceptive art critic. Ozone—rest in peace.[70]

On 27 April 2007, a new record high for the sale of Banksy's work was set with the auction of the work Space Girl and Bird fetching £288,000 (US$576,000) around 20 times the estimate at Bonhams of London.[71] On 21 May 2007 Banksy gained the award for Art's Greatest living Briton. Banksy, as expected, did not turn up to collect his award and continued with his anonymous status. On 4 June 2007, it was reported that Banksy's The Drinker had been stolen.[72][73] In October 2007, most of his works offered for sale at Bonhams auction house in London sold for more than twice their reserve price.[74]

Banksy has published a "manifesto" on his website.[75] The text of the manifesto is credited as the diary entry of British Lieutenant Colonel Mervin Willett Gonin, DSO, which is exhibited in the Imperial War Museum. It describes how a shipment of lipstick to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp immediately after its liberation at the end of World War II helped the internees regain their humanity. However, as of 18 January 2008, Banksy's Manifesto has been replaced with Graffiti Heroes No. 03, which describes Peter Chappell's graffiti quest of the 1970s that worked to free George Davis from imprisonment.[75] By 12 August 2009 he was relying on Emo Philips' "When I was a kid I used to pray every night for a new bicycle. Then I realised God doesn't work that way, so I stole one and prayed for forgiveness." A small number of Banksy's works can be seen in the movie Children of Men, including a stenciled image of two policemen kissing and another stencil of a child looking down a shop.[76]

Banksy, who "is not represented by any of the commercial galleries that sell his work second hand (including Lazarides Ltd, Andipa Gallery, Bank Robber, Dreweatts, etc.)",[77] claims that the exhibition at Vanina Holasek Gallery in New York City (his first major exhibition in that city) is unauthorised. The exhibition featured 62 of their paintings and prints.[78]

2008

In March, Nathan Wellard and Maev Neal, a couple from Norfolk, UK, made headlines in Britain when they decided to sell their mobile home that contains a 30-foot mural, entitled Fragile Silence, done by Banksy a decade prior to his rise to fame.[79] According to Nathan Wellard, Banksy had asked the couple if he could use the side of their home as a "large canvas", to which they agreed. In return for the "canvas", the Bristol stencil artist gave them two free tickets to the Glastonbury Festival. The mobile home purchased by the couple 11 years earlier for £1,000, was priced at £500,000.[80]

Also in March 2008, a stencilled graffiti work appeared on Thames Water tower in the middle of the Holland Park roundabout, and it was widely attributed to Banksy. It was of a child painting the tag "Take this—Society!" in bright orange. London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham spokesman, Councillor Greg Smith branded the art as vandalism, and ordered its immediate removal, which was carried out by H&F council workmen within three days.[81]

In late August 2008, marking the third anniversary of Hurricane Katrina and the associated levee failure disaster, Banksy produced a series of works in New Orleans, Louisiana, mostly on buildings derelict since the disaster.[82]

A stencil painting attributed to Banksy appeared at a vacant petrol station in the Ensley neighbourhood of Birmingham, Alabama on 29 August as Hurricane Gustav approached the New Orleans area. The painting, depicting a hooded member of the Ku Klux Klan hanging from a noose, was quickly covered with black spray paint and later removed altogether.[83] His first official exhibition in New York City, The Village Pet Store and Charcoal Grill, opened 5 October 2008. The animatronic pets in the store window include a mother hen watching over her baby Chicken McNuggets as they peck at a barbecue sauce packet, and a rabbit putting makeup on in a mirror.[84]

The Westminster City Council stated in October 2008 that the work One Nation Under CCTV, painted in April 2008 would be painted over as it was graffiti. The council said it would remove any graffiti, regardless of the reputation of its creator, and specifically stated that Banksy "has no more right to paint graffiti than a child". Robert Davis, the chairman of the council planning committee told The Times newspaper: "If we condone this then we might as well say that any kid with a spray can is producing art."[85] The work was painted over in April 2009. In December 2008, The Little Diver, a Banksy image of a diver in a duffle coat in Melbourne, Australia, was destroyed. The image had been protected by a sheet of clear perspex; however, silver paint was poured behind the protective sheet and later tagged with the words "Banksy woz ere". The image was almost completely obliterated.[86]

Banksy has also been long criticised for copying the work of Blek le Rat, who created the life-sized stencil technique in early 1980s Paris and used it to express a similar combination of political commentary and humorous imagery. Blek has praised Banksy for his contribution to urban art,[87] but said in an interview for the documentary Graffiti Wars that some of Banksy's more derivative work makes him "angry", saying that "It's difficult to find a technique and style in art so when you have a style and you see someone else is taking it and reproducing it, you don't like that."[88]

The Cans Festival (2008)

In London, over the weekend 3–5 May 2008, Banksy hosted an exhibition called The Cans Festival. It was situated on Leake Street, a road tunnel formerly used by Eurostar underneath London Waterloo station. Graffiti artists with stencils were invited to join in and paint their own artwork, as long as it did not cover anyone else's.[89] Banksy invited artists from around the world to exhibit their works.[90]

2009

In May 2009, Banksy parted company with agent Steve Lazarides and announced that Pest Control,[91] the handling service who act on his behalf, would be the only point of sale for new works. On 13 June 2009, the Banksy vs Bristol Museum show opened at Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, featuring more than 100 works of art, including animatronics and installations; it is his largest exhibition yet, featuring 78 new works.[92][93] Reaction to the show was positive, with over 8,500 visitors to the show on the first weekend.[94] Over the course of the twelve weeks, the exhibition was visited over 300,000 times.[95] In September 2009, a Banksy work parodying the Royal Family was partially destroyed by Hackney Council after they served an enforcement notice for graffiti removal to the former address of the property owner. The mural had been commissioned for the 2003 Blur single "Crazy Beat" and the property owner, who had allowed it to be painted, was reported to have been in tears when she saw it was being painted over.[96]

In December 2009, Banksy marked the end of the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference by painting four murals on global warming. One included the phrase, "I don't believe in global warming", with the words being submerged in water.[97] A feud and graffiti war between Banksy and King Robbo broke out when Banksy allegedly painted over one of Robbo's tags. The feud has led to many of Banksy's works being altered by graffiti writers.[98]

Exit Through the Gift Shop and United States (2010)

The world premiere of the film Exit Through the Gift Shop occurred at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, on 24 January. He created 10 street artworks around Park City and Salt Lake City to tie in with the screening.[99] In February, The Whitehouse public house in Liverpool, England, was sold for £114,000 at auction. The side of the building has an image of a giant rat by Banksy.[100]

In March 2010, a modified version of the work Forgive Us Our Trespassing–a kneeling boy with a spray-painted halo–was displayed at London Bridge Station on a poster. This version of the work did not possess the halo due to its stylistic nature and the prevalence of graffiti in the underground.[101] After a few days the halo was repainted by a graffitist, so Transport for London disposed of the poster.[101][102]

Banksy paints over the line between aesthetics and language, then stealthily repaints it in the unlikeliest of places. His works, whether he stencils them on the streets, sells them in exhibitions or hangs them in museums on the sly, are filled with wit and metaphors that transcend language barriers.

In April, to coincide with the premiere of Exit Through the Gift Shop in San Francisco, five of his works appeared in various parts of the city.[104] Banksy reportedly paid a San Francisco Chinatown building owner $50 for the use of their wall for one of his stencils.[105] In May 2010, seven new Banksy works of art appeared in Toronto, Canada.[106]

In May, to coincide with the premiere of Exit Through the Gift Shop in Royal Oak, Banksy visited the Detroit area and left his mark in several places in Detroit and Warren.[107] Shortly after, his work depicting a little boy holding a can of red paint next to the words "I remember when all this was trees" was excavated by the 555 Nonprofit Gallery and Studios. They claim that they do not intend to sell the work but plan to preserve it and display it at their Detroit gallery.[108] There was also an attempted removal of one of the Warren works known as Diamond Girl.[109] While in the United States, Banksy also completed a painting in Chinatown, Boston, known as Follow Your Dreams.[110]

In late January 2011, Exit Through the Gift Shop was nominated for a 2010 Oscar for Best Documentary Feature.[111] Banksy released a statement about the nomination, stating, "This is a big surprise... I don't agree with the concept of award ceremonies, but I'm prepared to make an exception for the ones I'm nominated for. The last time there was a naked man covered in gold paint in my house, it was me."[112] Leading up to the Oscars, Banksy blanketed Los Angeles with street art. Many people speculated if Banksy would show up at the Oscars in disguise and make a surprise appearance if he won the Oscar. Exit Through the Gift Shop did not win the award, which went to Inside Job. In early March 2011, Banksy responded to the Oscars with an artwork in Weston-super-Mare, UK, of a little girl holding the Oscar and pouting. Many people think that it is about 15-month-old Lara, who dropped and damaged her father's (The King's Speech co-producer Simon Egan) Oscar statue.[113] Exit Through the Gift Shop was broadcast on British public television station Channel 4 on 13 August 2011.

Banksy was credited with the opening couch gag for the 2010 The Simpsons episode "MoneyBart", depicting people working in deplorable conditions and using endangered or mythical animals to make both the episodes cel-by-cel and the merchandise connected with the program.[114] His name appears several times throughout the episode's opening sequence, spray-painted on assorted walls and signs. Fox sanitised parts of the opening "for taste" and to make it less grim. In January 2011, Banksy published the original storyboard on his website.[115] According to Banksy, the storyboard "led to delays, disputes over broadcast standards and a threatened walkout by the animation department." Executive director Al Jean jokingly said, "This is what you get when you outsource."[114]

2011–2013

In May 2011 Banksy released a lithographic print which showed a smoking petrol bomb contained in a 'Tesco Value' bottle. This followed a long-running campaign by locals against the opening of a Tesco Express supermarket in Banksy's home city of Bristol. Violent clashes had taken place between police and demonstrators in the Stokes Croft area. Banksy produced the poster ostensibly to raise money for local groups in the Stokes Croft area and to raise money for the legal defence of those arrested during the riots. The posters were sold exclusively at the Bristol Anarchists Bookfair in Stokes Croft for £5 each. In December, he unveiled Cardinal Sin at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. The bust, which replaces a priest's face with a pixelated effect, was a statement on the child abuse scandal in the Catholic Church.[116]

In May 2012 his Parachuting Rat, painted in Melbourne in the late 1990s, was accidentally destroyed by plumbers installing new pipes.[117] In July, prior to the 2012 Olympic Games Banksy posted photographs of paintings with an Olympic theme on his website but did not disclose their location.[118][119]

On 18 February 2013, BBC News reported that a recent Banksy mural, known as the Slave Labour mural portraying a young child sewing Union Flag bunting (created around the time of the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II), had been removed from the side of a Poundland store in Wood Green, north London, and soon appeared for sale in Fine Art Auctions Miami's catalogue (a US auction site based in Florida). News of this caused "lots of anger" in the local community and is considered by some to be a theft. Fine Art Auctions Miami had rejected claims of theft, saying it had signed a contract with a "well-known collector" and that "everything was above board"; despite this, the local councillor for Wood Green campaigned for the work's return.[120] On the scheduled day of the auction, Fine Art Auctions Miami withdrew the work of art from the sale.[121]

On 11 May, BBC News reported that the same Banksy mural was up for auction again in Covent Garden by the Sincura Group. The auction was scheduled to take place in June, and was expected to fetch up to £450,000.[122] On 24 September, after over a year since his previous piece, a new mural went up on his website along with the subtitle Better Out Than In.

Much criticism came forward during his series of works in New York in 2013. Many New York street artists, such as TrustoCorp, criticised Banksy, and much of his work was defaced.[123][124] In his column for The Guardian, satirist Charlie Brooker wrote in 2006 that Banksy's "work looks dazzlingly clever to idiots".[125]

Better Out Than In (2013)

On 1 October 2013, Banksy began a one-month "show on the streets of New York [City]", for which he opened a separate website[126] and granted an interview to The Village Voice via his publicist.[127]

A pop-up boutique of about 25 spray-art canvases appeared on Fifth Avenue near Central Park on 12 October. Tourists were able to buy Banksy art for just $60 each. In a note posted to his website, the artist wrote: "Please note this was a one-off. The stall will not be there again." The BBC estimated that the street-stall art pieces could be worth as much as $31,000. The booth was staffed by an unknown elderly man who went about four hours before making a sale, yawning and eating lunch as people strolled by without a second glance at the work. Banksy chronicled the surprise sale in a video posted to his website noting, "Yesterday I set up a stall in the park selling 100% authentic original signed Banksy canvases. For $60 each."[128][129][130] Two of the canvasses sold at a July 2014 auction for $214,000.[131]

Asked about the artist's presence in New York, then-New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who had led a citywide graffiti cleanup operation in 2002, said he did not consider graffiti a form of art.[132] One creation was a fiberglass sculpture of Ronald McDonald and a real person, barefoot and in ragged clothes, shining the oversized shoes of Ronald McDonald. The sculpture was unveiled in Queens but moved outside a different McDonald's around the city every day.[133][134][135] Other works included a YouTube video showing what appears to be footage of jihadist militants shooting down an animated Dumbo; travelling installations that toured the city including a slaughterhouse delivery truck full of stuffed animals and a waterfall; and a modified painting donated to a charity shop which was later sold in an online auction for $615,000.[136][137] Banksy also posted a mock-up of a New York Times op-ed attacking the design of the One World Trade Center after the Times rejected his submission.[138] The residency in New York concluded on 31 October 2013;[136][139] many of the pieces, though, were either vandalised, removed or stolen.[140]

2015–2018

In February 2015 Banksy published a 2-minute video titled Make this the year YOU discover a new destination about his trip to the Gaza Strip. During the visit, he painted a few artworks including a kitten on the remains of a house destroyed by an Israeli air strike ("I wanted to highlight the destruction in Gaza by posting photos on my website—but on the internet people only look at pictures of kittens") and a swing hanging off a watchtower. In a statement to The New York Times his publicist said,

I don't want to take sides. But when you see entire suburban neighbourhoods reduced to rubble with no hope of a future—what you're really looking at is a vast outdoor recruitment centre for terrorists. And we should probably address this for all our sakes.[141]

Banksy opened Dismaland, a large-scale group show modelled on Disneyland on 21 August 2015. It lampooned the many disappointing temporary themed attractions in the UK at the time. Dismaland permanently closed on 27 September 2015. The "theme park" was located in Weston-super-Mare, United Kingdom.[142][143] According to the Dismaland website, artists represented on the show include Damien Hirst and Jenny Holzer.[144] In December, Banksy created several murals in the vicinity of Calais, France, including the so-called "Jungle" where migrants then lived as they attempted to enter the United Kingdom. One of the pieces, The Son of a Migrant from Syria, depicts Steve Jobs as a migrant.[145]

In 2017, marking the 100th anniversary of the British control of Palestine, Banksy financed the creation of the Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem. This hotel is open to the public and contains rooms designed by Banksy, Sami Musa, and Dominique Petrin, and each of the bedrooms faces the wall. It also houses a contemporary art gallery.[146] 2018 saw Banksy return to New York five years after his Better Out Than In residency. A trademark rat running around the circumference of a clock-face, dubbed Rat race, was torn down by developers within a week of it appearing on a former bank building at 101 West 14th Street,[147] but other works, including a mural of imprisoned Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan on the famed Bowery Wall and a series of others across Brooklyn, remain on display.[148]

Love is in the Bin (2018)

In October 2018, a Banksy work, initially titled the Balloon Girl, was sold for £1m at London auction house Sotheby's. The purchaser of the work was an unnamed European woman. As the gavel hit the sound-block, an alarm sounded within the picture frame and the Banksy canvas passed through a shredder hidden within the frame, partially shredding the picture.[149][150] Banksy then posted an image of the shredding on Instagram captioned "Going, going, gone...".[151] After the sale, the auction house acknowledged that the self-destruction of the work was a prank by the artist.[152] The prank received wide news coverage around the world, with one newspaper stating that it was "quite possibly the biggest prank in art history".[150] Joey Syer, co-founder of an online platform facilitating art dealer sales,[153] told the Evening Standard: "The auction result will only propel this further and given the media attention this stunt has received, the lucky buyer would see a great return on the £1m they paid last night, this is now part of art history in its shredded state and we'd estimate Banksy has added a minimum of 50% to its value, possibly as high as being worth £2m+."[154] A man seen filming the shredding of the picture during its auction has been suggested to be Banksy.[155][156] Banksy has since released a video on how the shredder was installed into the frame and the shredding of the picture, explaining that he had surreptitiously fitted the painting with the shredder a few years previously, in case it ever went up for auction. To explain his rationale for destroying his own artwork, Banksy quoted Picasso: "The urge to destroy is also a creative urge".[157][158] (Although Banksy cited Picasso, this quote is usually attributed to Mikhail Bakunin.)[159] It is not known how the shredder was activated.[160] Banksy has released another video indicating that the painting was intended to be shredded completely. The video shows a sample painting completely shredded by the frame and says: "In rehearsals it worked every time..."[161]

The woman who won the bidding at the auction decided to go through with the purchase. The partially shredded work has been given a new title, Love is in the Bin, and it was authenticated by Banksy's authentication body, Pest Control Office Ltd. Sotheby's released a statement that said "Banksy didn't destroy an artwork in the auction, he created one", and called it "the first artwork in history to have been created live during an auction".[162][163] On 14 October 2021, the remains of the partially-shredded painting was reported by The Guardian to have been re-sold by Sotheby's auction house, for £18,582,000, in London.[149][164]

2018–2019

A two-sided graffiti piece, one side depicting a child tasting the falling snow, the other revealing that the snow is in fact smoke and embers from a dumpster fire, appeared on two walls of a steelworker's garage in Port Talbot in December.[165][166] Banksy then revealed that the painting was in fact his via an Instagram video soundtracked by the festive children's song "Little Snowflake".[167] Many fans of the artist went to see the painting and Plaid Cymru councillor for Aberavon, Nigel Thomas Hunt, stated that the town was "buzzing" with speculation that the work was Banksy's. The owner of the garage, Ian Lewis, said that he had lost sleep over fears that the image would be vandalised.[168] A plastic screen, partially funded by Michael Sheen, was installed to protect the mural, but was attacked by a "drunk halfwit".[169] Extra security guards were subsequently drafted to protect the graffiti piece.[170] In May 2019, the mural was moved to a gallery in the town's Ty'r Orsaf building.[171]

In early October 2019, Banksy opened a "pop-up shop" named Gross Domestic Product in Croydon, South London to strengthen his position in a trademark dispute with a greeting card company that had challenged his trademark on the grounds that he was not using it. In a statement, Banksy said "A [greeting card] company is contesting the trademark I hold to my art, and attempting to take custody of my name so they can sell their fake Banksy merchandise legally."[172] Mark Stephens, arts lawyer and founder of the Design and Artists Copyright Society, called the case a "ludicrous litigation" and is providing the artist legal advice. Stephens recommended opening the shop to Banksy on the grounds that it would show he is making use of his trademark, saying: "Because [Banksy] doesn't produce his own range of shoddy merchandise and the law is quite clear—if the trademark holder is not using the mark, then it can be transferred to someone who will."[173] On 4 October, greeting card distributor Full Colour Black publicly revealed itself as the company involved in the trademark dispute whilst rejecting Banksy's claims as "entirely untrue". The company claimed it had contacted Banksy's lawyers several times to offer to pay royalties.[174]

On 14 September 2020, the European Union Intellectual Property Office ruled in favour of Full Colour Black in the trademark dispute over Banksy's infamous "Flower Thrower".[175] The European panel judges in Full Colour Black Ltd v Pest Control Office Ltd [2020] E.T.M.R. 58) decided that Banksy's trademark was invalid as it had been filed in Bad Faith according to Regulation 2017/1001 art.59(1)(b).[176] The judges were not convinced that the opening of the artist's "pop-up shop" demonstrated a real intention to legitimise the trademark, condemning it as "inconsistent with the honest practices of the trade" [at 1141]. The artist's choice to be represented anonymously was not received well by the court either, noting that even if they found in favour of Banksy, legal rights could not be attributed to an unidentifiable person [1151]. However, counsel for the defence strongly argued that to reveal his identity would diminish the persona of the artist [at 1135]. Although not binding, the judges also referenced Banksy's previously critical statements about copyright, which contributed to the lack of sympathy for the artist's case [at 1144].

In October 2019, a 2009 painting by Banksy entitled "Devolved Parliament", showing Members of Parliament depicted as chimpanzees in the House of Commons, sold at Sotheby's in London for just under £9.9 million. On Instagram, the artist said it was a "record price for a Banksy painting" and "shame I didn't still own it".[177] At 13 feet (4.0 m) wide it is Banksy's biggest known work on canvas. The auction house stated: "Regardless of where you sit in the Brexit debate, there's no doubt that this work is more pertinent now than it has ever been."[177]

2020s

On 13 February 2020, the Valentine's Banksy mural appeared on the side of a building in Bristol's Barton Hill neighbourhood, depicting a young girl firing a slingshot of real red flowers and leaves.[178] In the early hours of Valentine's Day (14 February), Banksy confirmed this was his work on his Instagram account and website.[179] The painting was defaced just days after appearing.[180] Banksy dedicated a painting titled Painting for Saints or Game Changer to NHS staff, and donated it to the University Hospital of Southampton during the global coronavirus pandemic in May 2020.[181] The painting was sold for £14.4m (£16.8m including buyer premium) on 23 March 2021, which is a record for an artwork by Banksy. The proceeds from the sale would benefit a number of NHS-related organisations and charities.[182]

In March 2021, the image of an escaping prisoner appeared overnight on the side of Reading Prison.[183] Two days later Banksy claimed the artwork. The former prison's next use had been disputed locally, some wanting it to be used as an arts hub, while developers proposed it could be sold to a housing developer.[184] The escaping prisoner was said to resemble Oscar Wilde, who had been imprisoned in Reading Prison, with the "rope" as tied together bedsheets with a typewriter attached to the end.[184]

In August 2021, several Banksy artworks, collectively titled A Great British Spraycation, appeared in several East Anglian towns.[185][186] Banksy created an original artwork for the 2021 BBC One/Amazon Prime Video comedy The Outlaws. The image of a stencilled rat sitting on two spray cans signed by Banksy featured in the sixth episode of the first series, and was painted over by the character Frank, played by Christopher Walken, while he was cleaning a graffiti-covered wall as part of his Community Payback sentence.[187]

In November 2022, Banksy posted on social media images of a mural on the side of a damaged building at the town of Borodianka, appearing to confirm a visit to Ukraine following the Russian invasion.[188] He also created six murals in Kyiv, Irpin, Hostomel and Horenka.[189][190] One of the images he produced in Borodianka was of Russian president Vladimir Putin in a judo throw. The image has since been turned into a stamp in Ukraine.[191]

Banksy was accused of being "inconsistent with honest practices" when trying to trademark his image of a protester throwing a bouquet of flowers. The European Union trademark office threw out his trademark claim, "saying he had filed it in order to avoid using copyright laws, which are separate and would have required [him] to reveal his true identity. The ruling quoted from one of his books, in which he said 'copyright is for losers'."[192]

On St Patricks Day, 2024, a confirmed Banksy "mural" appeared overnight on a flank wall of a housing estate near to Finsbury Park.[193] The artwork is located in an area known as Upper Holloway, in the London Borough of Islington. The mural is behind a stark heavily pruned tree, which dominates the foreground.[194] The artwork's green shades and leafy foliage used paint that matches Islington's own municipal green, which is used on their housing estate nameplates. The sprawling artwork gives the impression of lush foliage in full leaf on the wall backdrop. An adjoining life size figure is stencilled onto the wall at ground level, showing a worker using a pressure washer, as if they were spontaneously spraying the artwork.[195] One of the first to visit the Banksy, was the local MP, Jeremy Corbyn.[195][196] Experts have speculated that the choice of subject and the location make it difficult to remove to sell at auction, as the context of the setting is everything and the sale value would be minimal.

In August 2024, he claimed credit for a number of black silhouette compositions, that appeared in London and were part of an animal-themed series. Various theories exist for what they mean and represent, with the artist himself declining to comment.[197][198]

Other artworks

Banksy has claimed responsibility for a number of high-profile artworks, including the following:

- At London Zoo, he climbed into the penguin enclosure and painted "We're bored of fish" in 7-foot-high (2.1 m) letters.[199]

- At London Zoo, he left the message "I want out. This place is too cold. Keeper smells. Boring, boring, boring." in the elephant enclosure.[200]

- In 2004, he placed the piece Banksus Militus Ratus into London's Natural History Museum.[201]

- In March 2005, he placed subverted artworks in the Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan as well as the Brooklyn Museum in Brooklyn.[202]

- In May 2005 Banksy's version of a primitive cave painting depicting a human figure hunting wildlife while pushing a shopping trolley was hung in gallery 49 of the British Museum, London.[203]

- In August 2005, Banksy painted nine images on the Israeli West Bank barrier, including an image of a ladder going up and over the wall and an image of children digging a hole through the wall.[55][204][205]

- In October 2005, Banksy designed six station IDs for Nickelodeon.[206]

- In April 2006, Banksy created a sculpture based on a crumpled red phone box with a pickaxe in its side, apparently bleeding, and placed it in a side street in Soho, London. It was later removed by Westminster Council.[207]

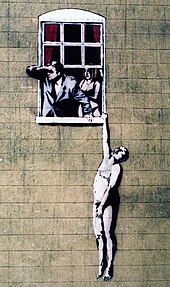

- In June 2006, Banksy created Well Hung Lover, an image of a naked man hanging out of a bedroom window on a wall visible from Park Street in central Bristol. The image sparked "a heated debate",[208] with the Bristol City Council leaving it up to the public to decide whether it should stay or go.[209] After an internet discussion in which 97% of the 500 people surveyed supported the stencil, the city council decided it would be left on the building.[208] The mural was later defaced with blue paint.[210]

- In August/September 2006, Banksy placed up to 500 copies of Paris Hilton's debut CD, Paris, in 48 different UK record stores with his own cover art and remixes by Danger Mouse. Music tracks were given titles such as "Why Am I Famous?", "What Have I Done?" and "What Am I For?". Several copies of the CD were purchased by the public before stores were able to remove them, some going on to be sold for as much as £750 on online auction websites such as eBay. The cover art depicted Hilton digitally altered to appear topless. Other pictures feature her with her chihuahua Tinkerbell's head replacing her own, and one of her stepping out of a luxury car, edited to include a group of homeless people, which included the caption "90% of success is just showing up."[211][212][213]

- In September 2006, Banksy dressed an inflatable doll in the manner of a Guantanamo Bay detainment camp prisoner (orange jumpsuit, black hood, and handcuffs) and then placed the figure within the Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ride at the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, California.[214][215]

- He makes stickers (the Neighbourhood Watch subvert) and was responsible for the cover art of Blur's 2003 album Think Tank.

- In September 2007, Banksy covered a wall in Portobello Road with a French artist painting graffiti of Banksy's name.[216]

- A guard/police officer with a balloon animal was painted in the Canadian city of Toronto in 2010, and has since been removed from its original location and preserved.[217]

- In July 2012, in the run up to the London 2012 Olympic games he created several pieces based upon this event. One included an image of an athlete throwing a missile instead of a javelin, evidently taking a poke at the surface to air missile sites positioned in the Stratford area to defend the games.[218][219]

- In April 2014, he created a piece in Cheltenham, near the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) headquarters, which depicts three men wearing sunglasses and using listening devices to "snoop" on a telephone box, evidently criticising the recent global surveillance disclosures of 2013. This was only confirmed by Banksy as his work later in June 2014.[220] This piece 'disappeared' on 20 August 2016 during renovations to the building it was on, and may have been destroyed.[221]

- In October 2014, Ten days before the 2014 Clacton by-election, Banksy painted a mural on a wall in Clacton which showed five grey pigeons holding three placards. They held the words "go back to Africa" "migrants not welcome", and "keep off our worms". They were directed towards a more colourful migratory swallow perched further along the same wire. The mural was removed by Tendring District Council who had received a complaint that "offensive and racist remarks" had appeared on a wall.[222]

- In June 2016, a 14 ft painting of a child with a stick chasing a burning tyre was found in the Bridge Farm Primary School in Bristol with a letter from Banksy thanking the school for naming one of its houses after him. BBC News reported that a spokesman for Banksy confirmed that the artwork was genuine. In the letter, Banksy wrote that if the members of the school did not like the painting, they should add their own elements.[223][224]

- In May 2017, Banksy claimed the authorship of a giant Brexit mural, painted on a house in Dover (Kent).[225]

- Banksy's Dream Boat, originally made for the Dismaland exhibition, was donated to the NGO Help Refugees (now called Choose Love) to help raise funds for the charity. The artwork was displayed in Help Refugees' London Choose Love pop-up shop in the run-up to Christmas 2018, and members of the public could pay £2.00 to enter a competition to guess the weight of the piece. The person with the closest guess would win Dream Boat.[226] The 'guess-the-weight' competition was seen as 'deliberately school fair' in style.[227]

-

Near Bethlehem – 2005

-

The Grin Reaper

Damaged artwork

Many artworks by Banksy have been vandalised, painted over or destroyed.

In 2008, in Melbourne, paint was poured over a stencil of an old-fashioned diver wearing a trench coat.[228] In April 2010, the Melbourne City Council reported that they had inadvertently ordered private contractors to paint over a rat descending in a parachute adorning the wall of an old council building behind the Forum Theatre.

In July 2011 one of Banksy's early works, Gorilla in a Pink Mask, was unwittingly painted over after the premises became a Muslim cultural centre. The art piece had been a prominent landmark on the exterior wall of a former social club in Eastville for over ten years.[229][230]

Many works that make up the Better Out Than In series in New York City have been defaced, some just hours after the piece was unveiled.[231][232] At least one defacement was identified as done by a competing artist, OMAR NYC, who spray-painted over Banksy's red mylar balloon piece in Red Hook.[233] OMAR NYC also defaced some of Banksy's work in May 2010.[234][235]

In the case of the 2013 vandalism of Banksy's Praying Boy in Park City, Utah, United States,[236] the perpetrator was tried, pled guilty, and convicted of criminal mischief.[237][238] The artwork was restored to its original state by a painting conservator, who was hired by the owners of the building where Praying Boy is located.[239]

Technique

Because of the secretive nature of Banksy's work and identity, it is uncertain what techniques he uses to generate the images in the stencils, though it is assumed he uses computers for some images due to the photographic quality of much of his work. He mentions in his book Wall and Piece that as he was starting to do graffiti, he was always either caught or could never finish the art in one sitting. He claims he changed to stencilling while hiding from the police under a rubbish lorry, when he noticed the stencilled serial number. He then devised a series of intricate stencils for minimising time and overlapping of the colour.

In a 2003 interview, Banksy described his technique, when making a piece in a public area, as "quick" and "I want to get it done and dusted."[26]

There exists a debate about the influence behind his work. Some critics claim Banksy was influenced by musician and graffiti artist 3D. Another source credits the artist's work to resemble that of French graffiti artist Blek le Rat. It is said that Banksy was inspired by their use of stencils, later taking this visual style and transforming it through modern political and social pieces.[240]

Banksy's stencils feature striking and humorous images occasionally combined with slogans. The message is usually anti-war, anti-capitalist or anti-establishment. Subjects often include rats, apes, policemen, soldiers, children, and the elderly.

In the broader art world, stencils are traditionally hand drawn or printed onto sheets of acetate or card, before being cut out by hand. This technique allows artists to paint quickly to protect their anonymity.[241] There is dispute in the street art world over the legitimacy of stencils, with many artists criticising their use as "cheating".[242][243]

In 2018, Banksy created a piece live as it was being auctioned at Sotheby's. The piece originally consisted of a framed painting of Girl with Balloon. While the bidding was in progress, a shredder was activated from within the frame, partially destroying the painting, and thus creating a new piece. The shredder had been preemptively built into the frame a few years prior in case the painting was put up for auction.[244] The new artwork, consisting of the half-shredded painting still in its frame, is titled Love is in the Bin.[245]

Political and social themes

| Part of a series on |

| Anti-consumerism |

|---|

Banksy once characterised graffiti as a form of underclass "revenge", or guerrilla warfare that allows an individual to snatch away power, territory and glory from a bigger and better equipped enemy.[56] Banksy sees a social class component to this struggle, remarking "If you don't own a train company then you go and paint on one instead."[56] Banksy's work has also shown a desire to mock centralised power, hoping that their work will show the public that although power does exist and works against you, that power is not terribly efficient and it can and should be deceived.[56]

Banksy's works have dealt with various political and social themes, including anti-war, anti-consumerism, anti-fascism, anti-imperialism, anti-authoritarianism, anarchism, nihilism, and existentialism. Additionally, the components of the human condition that his works commonly critique are greed, poverty, hypocrisy, boredom, despair, absurdity, and alienation.[247] Although Banksy's works usually rely on visual imagery and iconography to put forth their message, Banksy has made several politically related comments in various books. In summarising his list of "people who should be shot", he listed "Fascist thugs, religious fundamentalists, (and) people who write lists telling you who should be shot."[248] While facetiously describing his political nature, Banksy declared that "Sometimes I feel so sick at the state of the world, I can't even finish my second apple pie."[249]

Banksy's work has also critiqued the environmental impacts of big businesses. When speaking about his 2005 work Show me the Monet, Banksy explained:

The vandalised paintings reflect life as it is now. We don't live in a world like Constable's Haywain anymore and, if you do, there is probably a travellers' camp on the other side of the hill. The real damage done to our environment is not done by graffiti writers and drunken teenagers, but by big business... exactly the people who put gold-framed pictures of landscapes on their walls and try to tell the rest of us how to behave.[250]

Show me the Monet repurposes Claude Monet's Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies, with the inclusion of two shopping carts and an orange traffic cone. This painting was later sold for £7.5 million at Sotheby's Contemporary Evening Auction in 2020.[250]

During the 2017 United Kingdom general election, Banksy offered voters a free print if they cast a ballot against the Conservative candidates standing in the Bristol North West, Bristol West, North Somerset, Thornbury, Kingswood and Filton constituencies.[251] According to a note posted on Banksy's website, an emailed photo of a completed ballot paper showing it marked for a candidate other than the Conservative candidate would result in the voter being mailed a limited edition piece of Banksy art. On 5 June 2017 the Avon and Somerset Constabulary announced it had opened an investigation into Banksy for the suspected corrupt practice of bribery,[252] and the following day Banksy withdrew the offer stating "I have been warned by the Electoral Commission that the free print offer will invalidate the election result. So I regret to announce that this ill-conceived and legally dubious promotion has now been cancelled."[253]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Banksy referenced medical advice to self-isolate by creating an artwork in his bathroom.[254]

Philanthropy and activism

Banksy has donated a number of works to promote various causes, such as Civilian Drone Strike, which was sold in 2017 at £205,000 to raise funds for Campaign Against Arms Trade and Reprieve. It was part of the exhibition "Art the Arms Fair" set up in opposition to the DSEI arms fair.[255] In 2018, a sculpture titled Dream Boat, which was exhibited in Dismaland in 2015, was raffled off in aid of the NGO Help Refugees (now called Choose Love) for a minimum donation of £2 for every guesses of its weight in a pop-up Choose Love shop in Carnaby Street.[256] In 2002, he produced artwork for the Greenpeace campaign Save or Delete. He also provided works to support local causes; in 2013, a work titled The Banality of the Banality of Evil was sold for an undisclosed amount after a failed auction to support an anti-homelessness charity in New York.[257] In 2014, an artwork on a doorway titled Mobile Lovers was sold £403,000 to keep a youth club in Bristol open,[258][259] and he created merchandise for homeless charities in Bristol in 2019.[260]

Banksy has been producing a number of works and projects in support of the Palestinians since the mid-2000s, including The Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem.[261][262][263][264] In July 2020, Banksy sold three paintings forming a triptych titled Mediterranean Sea View 2017, which raised £2.2 million for a hospital in Bethlehem. The paintings were original created for The Walled Off Hotel, and are Romantic-era paintings of the seashore that have been modified with images of lifebuoys and orange life jackets washed up on the shore, a reference to the European migrant crisis.[265]

Banksy gifted a painting titled Game Changer to a hospital in May 2020 as a tribute to National Health Service workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.[266] It was later sold for £14.4m in March 2021 to benefit a number of NHS-related organisations and charities.[182]

In August 2020, it was revealed that Banksy had privately funded a rescue boat to save refugees at risk in the Mediterranean Sea. The former French Navy boat, renamed after Louise Michel, has been painted pink with an image of a young girl holding a heart-shaped safety float.[267]

Books

Banksy has published several books that contain photographs of his work accompanied by his own writings:

- Banging Your Head Against a Brick Wall (2001). ISBN 978-0-9541704-0-0.

- Existencilism (2002). ISBN 978-0-9541704-1-7.

- Cut It Out (2004). ISBN 978-0-9544960-0-5.

- Pictures of Walls (2005). ISBN 978-0-9551946-0-3.

- Wall and Piece (2007). ISBN 978-1-84413-786-2.

- You Are an Acceptable Level of Threat and if You Were Not You Would Know It (2012) [268]

Banging Your Head Against a Brick Wall, Existencilism, and Cut It Out were a three-part self-published series of small booklets.[269]

Pictures of Walls is a compilation book of pictures of the work of other graffiti artists, curated and self-published by Banksy. None of them are still in print, or were ever printed in any significant number.[270]

Banksy's Wall and Piece compiled large parts of the images and writings in his original three-book series, with heavy editing and some new material.[271] It was intended for mass print, and published by Random House.[271]

The writings in his original three books had numerous grammatical errors, and his writings in them often took a dark, and angry, and a (self-described) paranoid tone.[272][273][274] While the content in them was almost entirely kept in Wall and Piece, the stories were edited and generally took a less provocative tone, and the grammatical errors were resolved (presumably to make it suitable for mass market distribution).[271]

See also

References

- ^ "Banksy Unveils Valentine's Day Mural in His Hometown of Bristol". Observer. 14 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Holzwarth, Hans W. (2009). 100 Contemporary Artists A–Z (Taschen's 25th anniversary special ed.). Köln: Taschen. p. 40. ISBN 978-3-8365-1490-3.

- ^ "The Banksy Paradox: 7 Sides to the World's Most Infamous Street Artist Archived 2 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 19 July 2007

- ^ Baker, Lindsay (28 March 2008). "Banksy: off the wall". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Banksy fans fail to bite at street art auction". meeja.com.au. 30 September 2008. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "Banksy: Temporary by Design". Expose. 30 November 2018. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Abrams, Loney, How Does Banksy Make Money? (Or, A Quick Lesson in Art Market Economics) Archived 24 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Artspace, 30 March 2018

- ^ "Banksy film to debut at Sundance". BBC News. 21 January 2010. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ "Banksy's Exit Through the Gift Shop up for Oscar award". BBC Bristol. 25 January 2011. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ "2014 Webby Awards Person of the Year". Webbyawards.com. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b Hattenstone, Simon (17 July 2003). "Something to spray". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "Is this Banksy? Forgotten interview with elusive graffiti artist uncovered from ITV tape vaults". ITV News. 20 October 2022. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b Hines, Nico (11 March 2016). "The Secret Life of the Real Banksy, Robin Gunningham". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph, Property section, London, 7 July 2018, p. 5.

- ^ "Banksy: Map profiling backs theory that graffiti artist is Robin Gunningham". ABC News (Australia). 7 March 2016. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Banksy". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020 – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ Great Britain: Southwest England (PDF) (10th ed.). Lonely Planet. 2013. p. 282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2014.

- ^ Adams, Tim (14 June 2009). "Banksy: The graffitist goes straight". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ Sherwin, Adam (3 March 2016). "Banksy: Geographic profiling 'proves' artist really is Robin Gunningham, according to scientists". Independent. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Hauge, Michelle V.; Stevenson, Mark D.; Rossmo, D. Kim; Le Comber, Steven (3 March 2016). "Tagging Banksy: using geographic profiling to investigate a modern art mystery". Journal of Spatial Science. 61 (1): 185–190. Bibcode:2016JSpSc..61..185H. doi:10.1080/14498596.2016.1138246. ISSN 1449-8596. S2CID 130859901. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Banksy 'may abandon commercial art' Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 20 May 2015

- ^ "Banksy: the artist who's driven to the wall" Archived 26 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2015

- ^ Gillespie, James (5 August 2018). "Signed Banksy album artworks go up for sale". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Did Goldie just reveal who Banksy is?". BBC News. 23 June 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ a b Nanji, Noor (21 November 2023). "Banksy: Street artist confirms first name in lost BBC interview". BBC. UK. Archived from the original on 21 November 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ Jenkins, Nash. "Is Banksy Actually Massive Attack's Robert Del Naja?". Time. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Jaworski, Michael (2 September 2016). "Is Banksy actually a member of Massive Attack?". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "Neil Buchanan: Former Art Attack host denies Banksy rumours". BBC News. 7 September 2020. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Mr Banksy, I presume: the councillor who quit over claims he has a secret". the Guardian. 27 May 2022. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Alexander, Ella (20 October 2014). "Banksy not arrested: Internet duped by fake report claiming artist's identity revealed". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Banksy Bombhugger Print | Meaning & History". Andipa Editions. Archived from the original on 11 July 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Wright, Steve; Jones, Richard; Wyatt, Trevor (28 November 2007). Banksy's Bristol: Home Sweet Home. Bath: Tangent Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-906477-00-4.

- ^ "N-Igma fanzine showing examples of DBZ Graffiti tagged by Banksy, Kato and Tes". April 1999. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007.

- ^ "Street art show comes to Bristol". BBC News. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

Street art [...] erupted in the UK in the early 1980s [...] active on the Bristol scene at that time included Banksy, Nick Walker, Inkie and Robert del Naja, or '3D', of Massive Attack.

- ^ Reid, Julia (6 February 2008). "Banksy Hits Out at Street Art Auctions". London: Sky News. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

Along with Banksy, Bristol's graffiti heritage includes 3D, who went on to form Massive Attack, Inkie, and one of the original stencil artists Nick Walker.

- ^ Child, Andrew (28 January 2011). "Urban Renewal: Steve Lazarides continues to expand his street art empire". Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

He had discovered Banksy on a chance photo shoot in Bristol in 2001 while working as picture editor of Sleaze Nation magazine, and brought him to public attention along with a roster of other urban artists... Lazarides and Banksy parted company in 2009, a mysterious split about which both parties have remained tight-lipped.

- ^ a b Banksy (2005). Wall and Piece. Random House. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ Onyanga-Omara, Jane (14 September 2012). "Banksy in goal: The story of the Easton Cowboys and Cowgirls". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ "Banksy's mild mild west piece, Stokes Croft, Bristol". Bristol-street-art.co.uk. 27 November 2008. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Existencilism. Los Angeles, July 2002". Banksy Unofficial. 16 April 2017. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Banksy – Smiley Copper H". Phillips. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ "Banksy Existencilism Book". Art of the State. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "First time at auction for Banksy's 2002 art work, Leopard and Barcode, at Bonhams Urban art sale". artdaily.cc. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ "Banksy's Bristol". BBC Bristol. BBC. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Animals sprayed by graffiti artist". BBC News. 18 July 2003. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ "Banksy Show Tonight in London". 13 October 2005. Archived from the original on 11 November 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ Mix, Elizabeth (2011). "Bansky". Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T2093940.

- ^ "Banksy print donated to Bristol arts venue, The Cube". BBC News. BBC. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ Reinhard, Andrew (2016). "ANS Acquires Authentic Banksy £10 Diana Note". American Numismatic Society Blog. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981, s.18". legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "10 Things To Know About Banksy's Napalm". MyArtBroker. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Tichy, Anna (2021). "Banksy: Artist, Prankster, or Both?". New York Law School Law Review. 65 (1): 81–103.

- ^ Friedman, Jacob. "Napalm (Can't Beat That Feeling)". Hexagon Gallery. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ a b Jones, Sam (5 August 2005). "Spray can prankster tackles Israel's security barrier". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ a b c d Banksy Graffiti: A Book About The Thinking Street Artist Archived 18 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine by The Huffington Post, 30 August 2012

- ^ Oliver, Mark (18 September 2006). "Banksy's painted elephant is illegal, say officials". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Bowes, Peter (14 September 2006). "'Guerrilla artist' Banksy hits LA". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ "Banksy biography". Brian Sewell Art Directory (briansewell.com). 4 August 2005. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ a b Collins, Lauren (14 May 2007). "Banksy Was Here: The invisible man of graffiti art". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "UK, Magazine, Faces of the week". BBC News. 15 September 2006. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Beard, Matthew (6 April 2006). "Aguilera invests £25,000 in Banksy". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ^ "Banksy works set auction record". BBC News. 20 October 2006. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ^ "Your World Today (Transcript)". CNN. 4 December 2006. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2010. "Banksy Effect" mentioned near end.

- ^ "British graffiti artist joins elite in record sale". Reuters. 7 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ Roberts, Geneviève (19 January 2007). "Sotheby's makes a killing from Banksy's guerrilla artworks". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "Free house as part of mural sale". BBC News. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 13 February 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ "Iconic Banksy image painted over". BBC News. 20 April 2007. Archived from the original on 25 May 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ Addley, Esther (26 January 2007). "Blood on the tracks". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ Bull, Martin (2011). Banksy Locations & Tours: A collection of Graffiti Locations and Photographs in London, England. PM Press. ISBN 978-1-60486-320-8.

- ^ "Reuters UK: Elusive artist Banksy sets record price". Reuters.com. 25 April 2007. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "Banksy Statue Stolen". Stranger. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (2 April 2004). "But is it kidnap?". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Guerilla Artist, Archived 26 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Sky News, 24 October 2007

- ^ a b "Camp". Archived from the original on 19 January 2005.

- ^ "Banksy". Contact Music. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "A message from Banksy's lawyer". Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ "Banksy Pans His First New York Show". Artinfo. Louise Blouin Media. 7 December 2007. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Trailer a Banksy treasure". BBC. 6 March 2008. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ "Mobile 'art house' for sale". BBC News. 3 June 2008. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Banksy must have an Oyster card. He's gone west!". The London Paper. 11 March 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008.

- ^ "Banksy Paints Murals in New Orleans To Mark Hurricane Katrina Anniversary; Gallery 'Banksy Art in Big Easy'". Sky News. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008.

- ^ Banksy's Road Trip Continues: Takes On The KKK In Birmingham, Alabama Archived 21 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Marc Schiller, Wooster Collective

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (9 October 2008). "Where Fish Sticks Swim Free and Chicken Nuggets Self-Dip". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Banksy art is graffiti, rules town hall". The Sydney Morning Herald. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013.

- ^ Houghton, Janae (14 December 2008). "The painter painted: Melbourne loses its treasured Banksy". The Age. Australia. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011.

- ^ "Blek le Rat: This is not a Banksy". The Independent. London. 19 April 2008. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011.

- ^ Wells, Jeff (15 August 2011). "Guerrilla artists at war over style accusations". Western Daily Press. p. 3.

- ^ "Tunnel becomes Banksy art exhibit". BBC News. 2 May 2008. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ "Banksy Hosts The Cans Festival". Cool Hunting. 6 May 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ "What is Pest Control?". Pest Control Office. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ Cafe, Rebecca (12 June 2009). "Banksy's homecoming reviewed". BBC Bristol. BBC. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ^ Sawyer, Miranda (13 June 2009). "Take a stuffy old institution. Remix. Add wit. It's Banksy v the museum". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- ^ "Thousands flock to Banksy show in Bristol". Bristol Evening Post. Bristol News and Media. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ Cafe, Rebecca (31 August 2009). "Banksy art show draws in 300,000". BBC Bristol. BBC. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ^ "Blur Banksy is ruined by mistake". BBC News. 5 September 2009. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Banksy art tackles global warming Archived 3 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 21 December 2009.

- ^ Fuertes-Knight, Jo. "My Graffiti War with Banksy By King Robbo". Sabotage Times. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Means, Sean P. (21 January 2010). "Famous 'tagger' Banksy strikes in Utah". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Sharpe, Laura (18 February 2010). "Liverpool Banksy rat pub building sold for £114,000 at auction". The Liverpool Daily Post. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010.

- ^ a b "London Underground Banksy work regains its halo". BBC News. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "Underground mystery as Banksy work regains its halo". London Evening Standard. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Fairy, Shephard (29 April 2010). "Time 100: Banksy". Time. No. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Street Artist Banksy Marks the Mission". The San Francisco Chronicle. 23 April 2010. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ Banksy in San Francisco | San Francisco Luxury Living Archived 27 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Sfluxe.com (24 April 2010). Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Banksy comes to Toronto". Torontoist. 9 May 2010. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Wright, Travis R (10 May 2010). "Banksy Leaves a Rat in Warren and a Diamond in Detroit". Metro Times blogs. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Stryker, Mark. "Graffiti artist Banksy leaves mark on Detroit and ignites firestorm". Archived from the original on 18 May 2010.

- ^ Davis, Becks (12 May 2010). "Street Artist Banksy Tags Detroit". Detroit Moxie. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010.

- ^ "Banksy makes his mark across America". The Independent. 7 June 2010. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Banksy nominated for Oscar. Oscar.go.com. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Banksy statement to Oscar nomination Archived 1 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Nme.com (27 January 2011). Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Banksy responds to Oscars Archived 11 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Swns.com (9 March 2011). Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Banksy creates new Simpsons title sequence". BBC News. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Original Storyboard from banksy.co.uk, archived at web.archive.org

- ^ "Banksy unveils church abuse work". BBC News. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011.

- ^ "Banksy rat destroyed by builders". ABC News (Australia) (16 May 2012). Archived 17 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 November 2012.