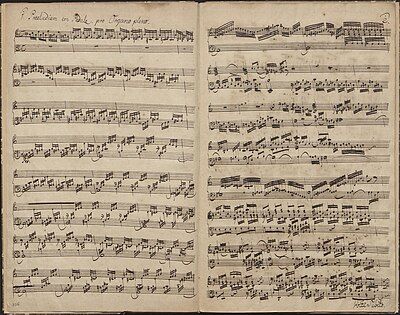

Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2022) |

Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543 is a piece of organ music written by Johann Sebastian Bach[1] sometime around his years as court organist to the Duke of Saxe-Weimar (1708–1713).[2]

Versions and sources

[edit]According to David Schulenberg, the main sources for BWV 543 can be traced to the Berlin circle around Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Johann Kirnberger. The copyist associated with C. P. E. Bach has only been identified as "Anonymous 303"; the manuscript is now housed in the Berlin State Library. Although less prolific than copyists like Johann Friedrich Agricola, from the many hand-copies circulated for purchase by Anon 303, including those from the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin recovered from Kyiv in 2001, commentators agree that the professional copyist must have enjoyed a close relationship with C. P. E. Bach. The other secondary source for BWV 543 came through the copyist Johann Gottfried Siebe and Kirnberger. The manuscript became part of the Amalienbibliothek, the music library of Princess Anna Amalia of Prussia; it is now in the Berlin State Library. There is an additional source from the copyist Joachim Andreas Dröbs whose score for BWV 543 formed part of a collection by Johann Christian Kittel, now in the Leipzig University Library. The sources for BWV 543a, which is presumed to be an earlier version of BWV 543 differing markedly from the prelude but identical to the fugue, originate in Leipzig. The main source was an unidentified copyist associated with Bach's pupil Johann Ludwig Krebs; the manuscript is now in the Berlin State Library. A secondary source is from the copyist Johann Peter Kellner, written around 1725 and also now in the Berlin State Library. An additional source is the score made by the copyist Michael Gotthardt Fischer; it is now stored in the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library of Yale University.[3][4]

Prelude

[edit]

There are two versions of the Prelude, both dating from the same period in Weimar (1708–1713). The versions of the fugue are identical, whereas the two versions of the prelude are distinct, the first version BWV 543/1a is shorter and presumed to be the earlier. The sources for BWV 543 are summarised in the section above. The differences between the two versions of the prelude are discussed in Williams (2003): the earlier version is 43 bars long, while the later version is 53 bars long. The main differences occur in bars 1–6 of BWV 543a/1 and bars 1–9 of 543/1 where the descending semiquaver broken-chord figures are altered and truncated. The same applies for the corresponding passages for bars 17–18 in BWV 543a/1 and bars 26–28 in BWV 543/1. In addition the triplet semiquavers in the later prelude are notated as demisemiquavers. As Beechey (1973) observes, "The more serious question concerning the opening passage of the prelude in its early and later versions is the fact that Bach changed his demisemiquavers to semiquavers [...] and in doing so preserved a calmer mood and a less rhapsodic feeling in the music; this change, however, does not and cannot mean that the early version is wrong or that the composer was mistaken. In the later version Bach was thinking on a larger scale and was considering the fugue and companion movement on a similarly large scale [...] The simplest way of extending the early prelude was to double the note values of the passages cited and thus make its flow more even."[1][5][6]

Fugue

[edit]The musicologist Peter Williams has pointed out that the catchy "lengthy sequential tail" of this fugue subject (its last 3 bars) "easily confuse[s] the ear about the beat" and is harmonically an exact "paraphrase" of the sequence in bars 6-8 of Vivaldi's double violin concerto Op. 3 No. 8 in A minor (RV 522, from L'estro armonico). Bach arranged this Vivaldi concerto as his solo organ "concerto" BWV 593, probably in 1714–16.[1]

This 4-voice fugue BWV 543 has been compared to Bach's harpsichord Fugue in A minor, BWV 944, a 3-voice fugue that was probably written in 1708, and this organ fugue has even been called "the final incarnation" of BWV 944.[7] (A similarity had been mentioned by Wolfgang Schmieder, editor of the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis.) However, the idea of any close relationship (let alone a reincarnation) has been challenged.[8] Williams writes that the fugue "has often been likened to the keyboard fugue BWV 944 [...] and claimed as some kind of version of it [but] the resemblances – contours of subject and countersubject, a perpetuum mobile element, a rather free close – are too slight" to support the comparisons. Williams also cites similarities "between the subject’s outline and that of the A minor Fugue BWV 559 from the Eight Short Preludes and Fugues, or between the pedal figures in both Preludes' closing stages [and] in the Prelude’s opening [right hand] figure, in a Corrente in Vivaldi’s Op. 2 No. 1, of 1709, and in a Fugue in E minor by Pachelbel." Aside from Williams' observations about the fugue subject, the fugues BWV 543 and 944 differ in their larger outlines: their harmonic structure and the series of expositions and episodes are not parallel.[1]

Musical structure

[edit]Prelude

[edit]Although Philipp Spitta has seen elements of northern traditions of the early Prelude BWV 543a/1 typical of the school of Buxtehude, Williams (2003) has pointed out that the same features are also present in the later version BWV 543/1. These include solo passages at the start; semiquaver passages with hidden two- or three-part counterpoint in both the manuals and pedals; virtuosic demisemiquaver passages with trills leading to a cadence; and running semiquaver and demisemiquaver figures throughout, including at the start and in the coda. The traditional aspects are the semiquaver arpeggiated passage work with its "latent counterpoint" which incorporates a descending chromatic bass line. The semiquaver figures begin as a solo in the manual:[1][2]

and then, after a lengthy demisemiquaver embellishment over a tonic pedal point, are heard again in the pedal. The highly embellished cadence that follows—full of manual runs over sustained pedal notes—leads into a contrapuntal exploration of the opening material in sequence; this is followed by a very free peroration. Features which distinguish Bach's writing from seventeenth-century compositions include its regular tempo throughout; the careful planning of climaxes; the well-judged changes from semiquavers, to semiquaver triplets and then demisemiquavers. After bars 36, there are semiquaver motifs in the manuals answered by similar motifs in the pedals: there are brisé effects similar to those found in chorale prelude BWV 599 or the Passacaglia, BWV 582/1; and pedal motifs similar to those found in the chorale prelude BWV 643. For both of these chorale preludes from the Orgelbüchlein, however, it is the systematic use of motifs that establish a particular musical mood. The Toccata-like Prelude in A minor—in the stylus phantasticus—bears the hallmarks of Bach's early, north German-influenced style, while the fugue could be considered a later product of Bach's maturity.[1][2]

Fugue

[edit]

The versions of the 4-part fugue for BWV 543a and BWV 543 are identical; it lasts 151 bars. The theme can be traced back to Bach's organ concerto in A minor BWV 593, transcribed for organ from Antonio Vivaldi's concerto for two violins, Op.3, No.8, RV 522, part of his collection L'estro armonico. The fugue can be broken up into sections as follows:

- Bars 1–30. There is an exposition for each of the four parts, three in the manuals and one in the pedal, each lasting four and a half bars with a connecting half bar. The main subject starts with a head-motif which is curtailed by descending sequential arpeggiated figures. There is also a simultaneous countersubject in response to the new fugal entries. After the entries by the two higher voices, there is an episode in bars 11–14 as a codetta, heralding the first entry of the lower manual part. There is a similar six and a half bar codetta before the pedal entry sounds, but now the subject is off kilter, with the pedal entry starting on the off beat.[1]

- Bars 31–50. There is a four and half bar episode, developing the exposition, with the 3 manual parts in the countersubject and busy arpeggiated sequences in the pedals. The lower manual part then remains silent, as new freely developed thematic material begins: first in parallel sixth semiquavers in the upper manuals accompanied by quaver motifs in the pedals; and then with briefly semiquaver motifs in the pedals before a three bar trio between the upper parts and pedal, leading to a hemiola with a cadence on the tonic A minor (thus, in the baroque musical style, two beats of 6/8 time are replaced by three beats of 3/4 time, ornamented on the last beat for the cadence). The highest part now sounds the fugal theme, with simple accompaniment from motifs in the other upper manual part and the pedal: their trio is truncated by a further hemiola with ornamental cadence.[1]

- Bars 51–61. The lowest manual part enters in the dominant key, with a disguised version of the head-motif of the fugal theme. The pedal part remains silent, while, led by the lowest manual parts, the upper parts together play "circle of fifths": baroque musical sequences, with successions of harmonies that at each stage progress from dominant to tonic (or tonic to dominant).[1]

- Bars 61–95. This passage, for keyboard alone, is a new restatement of the fugue theme in C major, the relative major. The manual entry is en taille, from the French "in the waist," a tenor voice often played on a tierce or cromorne organ stop. In this case the fugal entry plays between the highest and lowest parts on the manuals. There is then an episode involving circle of fifths; an answering entry on bar 71 in the highest part; a pedal point in the lowest manual part, above a circle of fifths episode; and finally, as the lowest part is silenced, a duet between the upper parts, with a further restatement of the fugal theme in the lower part followed by another circle of fifths episode.[1]

- Bars 95–135. The first bars of this section involve a stretto passage: the pedal starts to play the fugue theme as usual, only to be taken up by the true fugue theme, off the beat and in the lowest manual part. Between bars 113 and 115, there is a further fugal entry in E minor in the middle manual part. Finally, at bar 131, there is the last fugal entry in the lowest manual part. After each of these fugal entries, episodes are freely developed over brief pedal points. In bars 132–134, the rising quaver scales in the pedals lead up to the final section.[1]

- Bars 135–151. There is a pedal point for four bars, with the upper manual parts accompanying the arpeggio motifs in the lowest manual part; that is followed by solo arpeggio pedalwork for seven bars; then, in a virtuosic cadenza-like coda, the regular semidemiquaver passage-work in the highest part leads up to an emphatic closing cadence in the minor key.[1]

The fugue is in 6

8 time, unlike the prelude, which is in 4

4 time. The fugue theme, like that of the prelude, is composed of arpeggiated chords and downward sequences, especially in its later half. Due to the sequential nature of the subject, the majority of the fugue is composed of sequences or cadences. The Fugue ends in one of Bach's most toccata-like, virtuosic cadenzas in the harmonic minor. Unlike most of Bach's minor-key keyboard works, it ends on a minor chord rather than a picardy third.[1]

Reception and arrangements

[edit]In his book on the reception of Bach's organ works in nineteenth-century Germany, the musicologist Russell Stinson immediately singles out Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms. In his introduction Stinson writes that experiencing these works "through the eyes and ears of these four titans immeasurably increases one's appreciation of the music." He picks out the fugue of BWV 543, nicknamed "The Great", as a quintessential example: its performance on the organ, where Mendelssohn effortlessly mastered the pedalwork; the fugue as a compositional model for both Mendelssohn and Brahms; the piano transcription regularly played by Liszt and Brahms; and the actual publication of Liszt's transcription, which inspired budding pianists. Women also played an important role: Clara Schumann as a highly reputed pianist and fellow advocate of Bach; and Mendelssohn's accomplished sisters, Fanny and Rebecka, who played the fugue in piano arrangements either together or with their brother Felix. As further evidence of the reputation of the fugue, Stinson observes that, "Schumann attended and reviewed Mendelssohn's only public performance of the movement, Liszt heard Clara play her piano transcription of it, and Clara eventually played Liszt's transcription."[9]

Mendelssohn family

[edit]Through their connection with the publisher C. F. Peters, the family of Fanny, Rebecka and Felix Mendelssohn are known to have played in private or performed in public Bach organ works arranged for two pianos or piano four-hands.[9]

Liszt's transcription

[edit]

Because of the piece's overall rhapsodic nature, many organists play this piece freely, and in a variety of tempi; it can be easily transcribed to a different instrument. Liszt included it in his transcriptions of the "six great preludes and fugues" BWV 543–548 for piano (S. 462), composed in 1839–1840 and published in 1852 by C. F. Peters.[10][11][12]

As a child, Liszt had been instructed by his father to master the keyboard works of Bach, with daily exercises on fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier (WTC). As a concert pianist, however, Liszt was not drawn to the organ. In 1857, having attended a Bach organ recital at the Frauenkirche, Dresden, which captivated both Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim, Liszt's reaction had been, "Hm, dry as bones." Nevertheless, as far as Bach's music is concerned, Liszt became highly influential as a performer, transcriber and teacher.[12]

Already in 1836, early in his career, it is known that Liszt had developed a reverence for Bach's great "six preludes and fugues", BWV 543–548, or "The Great Six" fugues as they became known in the nineteenth century. In fact the previous year Liszt had eloped to Geneva with Marie d'Agoult, with whom they eventually had three children. After the birth of their first child, Liszt asked his mother in 1836 for his copies of The Art of the Fugue and the Great Six. In the same year Liszt became close to the circle of George Sand and Adolphe Pictet, both Bach devotees. Three years later, writing to Pictet from Rome, Liszt praised the "magnificent" Six Fugues, offering to send him a copy if he lacked one. During his period in Rome, there was a service at the church of the French Embassy, where Liszt performed one of Bach's fugues: according to Stinson, Liszt is unlikely to have had the pedal technique required for any of the Great Six, so almost certainly it was one of the WTC. When Liszt moved to Berlin in 1841, the first concerts where his new piano transcriptions of the Great Six were heard were at the beginning of 1842, with the E minor fugue of BWV 548 at the Singakademie and the A minor fugue of BWV 543 in Potsdam.[12]

During that period, as a travelling musician, Liszt's pianistic pyrotechnics proved a huge attraction for concert-goers. The term Lisztomania was coined by Heinrich Heine in 1844 to describe the frenzy generated by his Berlin audiences, even amongst the musically informed. Liszt performed the A minor fugue regularly in Berlin between 1842 and 1850. During this period there were reports that Liszt resorted to stunts in front of live audiences, which prompted possibly deserved charges of charlatanry. In August 1844, Liszt stayed in Montpellier while performing in the region. While there, he met up with his friend Jean-Joseph Bonaventure Laurens, an organist, artist and writer. His friendship with the Schumanns and Mendelssohn and the Bach library he had assembled with them enabled Laurens to become one of the main experts on Bach organ works in France. 40 years later, Laurens' brother recalls their lunchtime conversation. In semi-serious banter, Liszt demonstrated three ways of playing the A minor fugue, a work that Laurens said was so hard that only Liszt might be the only one capable of tackling it. Liszt first gave a straight rendition, which was a perfect classical way of playing; then he gave a second more colourful but still nuanced rendition, which was equally appreciated; finally he provided a third rendition, "as I would play it for the public ... to astonish, as a charlatan!" Laurens then writes that, "lighting a cigar that passed at moments from between his lips to his fingers, executing with his ten fingers the part written for the pedals, and indulging in other tours de force and prestidigitation, he was prodigious, incredible, fabulous, and received gratefully with enthusiasm." Stinson (2006) points out that this kind of gimmickry was not uncommon at that time: "Indeed, [Liszt] is reported to have accompanied Joachim in the last movement of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto with a lighted cigar in his right hand the entire time!"[12]

In 1847, exhausted by his years on the concert circuit, Liszt retired to Weimar, where in 1848 he was appointed to be Kapellmeister at the Grand Duchy, the same role once filled by Bach. He initially was there for 13 years. Later he also divided his time between Budapest and Rome, teaching masterclasses. His new mistress was Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, who lived in a country estate at Woronińce in Ukraine; their companionship continued until Liszt's death. After three months in Woronińce, Liszt set to work on preparing the transcriptions of BWV 543–548. He chose the edition of Haslinger as a starting point, although probably also consulted the 1844 Peters edition. He was aided by the copyist Joachim Raff at various stages. Stinson (2006) gives the technical details of the different stages of transcription, which started from simple notes in Haslinger's score: these are recorded in the Goethe- und Schiller-Archive in Weimar. In his book, Stinson gives the A minor prelude of BWV 543 as the main example for how the process works, with particular attention given to how the pedal part can be filled in from the right hand. In the published version of Peters, Liszt chose to place the B minor prelude and fugue, BWV 544 last, altering the standard order in most of the editions for organ. With his view that Bach was "the St. Thomas Aquinas of music," Liszt ultimately had an almost religious zeal for respecting the score as written by Bach. As Stinson concludes, "over thirty years later Liszt commented to his piano class that it would have been “sinful” of him to add dynamic markings to the score of the A-minor fugue, since “the great Bach” had written none himself." Even in his later years, Liszt's A minor fugue remained one of his favourites: when he was invited to play at a private evening concert, with guests of honour Prince Albert of Prussia and his wife Princess Marie of Saxe-Altenburg, Liszt's first choice was the fugue and in his letter of thanks disclosed that Clara Schumann now as matter of course played his transcription rather than her own. In the 1880s, American pupils of Liszt, particularly Carl Lachmund, attested to his pleasure in hearing or speaking about the fugue, be it at a Weimar dinner party in his honour, where students sang it together, or in a masterclass discussing its performance. As Stinson points out, "Liszt's lifelong advocacy of this movement—as a performer, transcriber, and teacher—is surely one reason for its enduring popularity."[12]

Max Reger

[edit]

In 1895–1896, Max Reger made a number of arrangements of Bach's organ works, both for piano duet and for piano solo. The four-hand arrangement of BWV 543 comes from his collection Ausgewählte Orgelwerke, published in 1896 by Augener & Co in London and G. Schirmer in New York, contains ten pieces, with a high level of difficulty.[13][14][15] While making the transcription in 1895 in Wiesbaden, Reger commented dismissively to Ferruccio Busoni, the Italian composer and fellow Bach transcriber, that, "It’s too bad that Franz Liszt did such a bad job on his transcriptions of Bach’s organ pieces—they’re nothing but hackwork."[15][16] In 1905 Reger became the regular piano partner of Philipp Wolfrum, director of music at Heidelberg University and author of a two-volume monograph on Bach. Their collaboration not only involved concert tours, but a special "Bach–Reger–Musikfest" in June 1913, organized as the fifth Heidelberg Music Festival. As a Bachian, organist and composer, Reger's views on Bach reception, in particular his public writings, are well recorded in the literature.[17] According to Anderson (2006a), in 1905, Reger was one of several German musicians, artists and critics surveyed by Die Musik on J.S. Bach's contemporary relevance (“Was ist mir Johann Sebastian Bach und was bedeutet er für unsere Zeit?”); as Anderson concludes, "The brevity of Reger’s “essay,” however, does not prevent the emergence of certain themes that are developed at greater length elsewhere in his writings: the nature of progress, the “illness” of contemporary musical culture, German nationalism, the guilt of the critics." In his much cited response, Reger wrote: "Sebastian Bach is for me the Alpha and Omega of all music; upon him rests, and from him originates, all real progress! What does—pardon, what should—Sebastian Bach mean for our time? A most powerful and inexhaustible remedy, not only for all those composers and musicians who suffer from “misunderstood Wagner,” but also for all those “contemporaries” who suffer from spinal maladies of all kinds. To be “Bachian” means to be authentically German, unyielding. That Bach could be misjudged for so long, is the greatest scandal for the “critical wisdom” of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries."[15][18][19]

In 1898, before any recognition for his music, Reger had travelled to St. Paul's Church, Frankfurt am Main to hear a recital of his works by the Berlin organist Karl Straube. They immediately shared an affinity for Bach's works and, in turn, Straube became Reger's most important promoter. In 1903 Straube had gone to teach at the conservatory in Leipzig, where he became organist at the Thomaskirche and later, in 1918, the Thomaskantor, a position once filled by Bach. Although originally from a village in Lower Bavaria, in 1907 Reger also succeeded in securing a teaching position at the Leipzig conservatory.[20] Straube's organ playing reflected late-romantic style: as in Reger's works, his use of the Walze and Swell roller mechanisms, pioneered by Wilhelm Sauer, permitted rapid changes of dynamics and orchestral colour.[21] In the case of the fugue of BWV 543, this drew criticism, even amongst ardent supporters of Straube, when unorthodox registration resulted in a perceived sacrifice to clarity during brilliant passage work.[20] In 1913 a new edition of Bach's complete organ works was published by C. F. Peters, edited by Straube, with detailed instructions on organ technique, following his methods. After Reger's death in 1916, a series of Straube's pupils in Leipzig helped maintain that tradition, despite the Orgelbewegung, the German organ reform movement that had started in the 1920s.[20][22] One of Straube's Leipzig pupils, Heinrich Fleischer, was called up for service in Germany in 1941; in Russia he was injured in an automobile accident in 1943; after three days of surgery at Równo, he was informed that two fingers of his left hand would have to be amputated, one completely and the other partially. Despite his injuries, he moved through US university appointments to the University of Minnesota, re-establishing his career as an organist.[23][24][25] In 2018, Dean Billmeyer, from the same university and a former organ pupil of Fleischer, wrote an account on the performance tradition of Straube, accompanied by performances from Germany, including a recording of BWV 543 from the Sauer organ in the Michaeliskirche, Leipzig.[26]

Other transcriptions

[edit]- Simon Sechter (1788–1867) made one of the first four-hand piano transcriptions of BWV 543 in 1832 for the Viennese publisher Tobias Haslinger. The original manuscript, "Sebastian Bachs Orgelfugen für das Pianoforte: zu 4 Händen eingerichtet," has been digitised by the Austrian National Library.[27][28] There was also a four-hand piano arrangement of BWV 543–548 in 1832 by an unknown copyist, now held in the Berlin State Library.[29][30]

- Carl Voigt (1808–1888) made an arrangement of BWV 543 for piano duet around 1834, for the publishing company of Georg Heinrich Hedler in Frankfurt am Main.[31]

- Franz Xaver Gleichauf (1801–1856), a pupil of Johann Nepomuk Schelble and reputed Bach copyist, arranged BWV 543 for piano duet (or piano four hands), in a two volume album published in 1846 by C. F. Peters in Leipzig, with a medium level of difficulty. The album was republished by International Music Company in 1962.[32][33][34]

In popular culture

[edit]The Oscar-winning Italian composer Ennio Morricone has described the relation between BWV 543 and the main themes of certain films he scored. In Alessandro De Rosa's 2019 book, Ennio Morricone: in his own words, Morricone described the main musical theme for the 1970 film Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion as an "ambiguous tango." Later he realized that it reminded him of the theme of The Sicilian Clan, released one year earlier. He remarked "[a]fter reflecting further on this resemblance, I then realized that the other theme as well was derived from my own idealization of Johann Sebastian Bach's Fugue in A Minor BWV 543. In search of originality, I found myself trapped in one of my deepest loves."[35][36]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Williams, Peter (2003). "Preludes and Fugues (Praeludia) BWV 531–552". The Organ Music of J. S. Bach (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–95. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511481871.004. ISBN 978-0-521-89115-8.

- ^ a b c Jones, Richard D. P. (2007). The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume I: 1695–1717: Music to Delight the Spirit. Oxford University Press. pp. 179–186. ISBN 9780198164401. Extended footnote 1, with references in German.

- ^ Bach 2014 Commentary

- ^ Ishii, Akira (2013). "Johann Sebastian Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, and Johann Jacob Froberger: The Dissemination of Froberger's Contrapuntal Works in Late Eighteenth-Century Berlin". Bach. 44 (1). Riemenschneider Bach Institute: 75–86. JSTOR 43489873. "Anonymous 303" and his hand-copies of J.S. Bach's keyboard works

- ^ Bach, Johann Sebastian (2014). Schulenberg, David (ed.). Complete Organ Works – Urtext. Vol. 2, Preludes and Fugues II. Breitkopf & Härtel. ISMN 979-0-004-18373-1. Introduction Archived 13 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine in German and English. Commentary Archived 13 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine in English, with "synoptic view" facility for split-screen viewing of BWV 543/1 and BWV 543a/1

- ^ "Prelude, a (early version) BWV 543/1a". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 14 May 2019.

- ^ Johnston, Blair (2005). Woodstra, Chris; Brennan, Gerald; Schrott, Allen (eds.). All Music Guide to Classical Music: The Definitive Guide to Classical Music. Backbeat Books. ISBN 9780879308650. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Beechey, Gwilym (1973). "Bach's A Minor Prelude and Fugue: Some Textual Observations on BWV 543". The Musical Times. 114 (1566): 831–833. doi:10.2307/957607. JSTOR 957607.

- ^ a b Stinson, Russell (2006). The reception of Bach's organ works from Mendelssohn to Brahms. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517109-8.

- ^ Preludes and Fugues by J.S. Bach, S.462: Liszt's piano transcriptions of BWV 543–548 at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ Transcriptions Archived 2 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine at pianosociety

.com - ^ a b c d e Stinson 2006, pp. 102–125

- ^ Anderson, Christopher S., ed. (2013). Twentieth-Century Organ Music. Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 9781136497896.

- ^ Reger, Max (1890). "Johann Sebastian Bach, Präludium und Fuge, A-Moll". Augener. hdl:1802/4631 – via Eastman School of Music–Sibley Music Library, University of Rochester.

- ^ a b c Rollings, Benjamin D. (2020). From pipe organ to pianoforte: the practice of transcribing organ works for piano (PDF) (Thesis). Indiana University.

- ^ Stinson 2006, p. 114 See "Letters of composers" (1946) compiled by Gertrude Norman and Miriam Lubell Shrifte.

- ^ Anderson, Christopher S. (2004). "Reger in Bach's Notes: On Self-Image and Authority in Max Reger's Bach Playing". The Musical Quarterly. 87 (4): 749–770. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdh026.

- ^ Anderson, Christopher (2006a). Selected Writings of Max Reger. Routledge. ISBN 9780203958858.

- ^ Frisch, Walter (2001). "Reger's Bach and Historicist Modernism". 19th-Century Music. 25 (2–3): 296–312. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.25.2-3.296. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2001.25.2-3.296. S2CID 190709449.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Christopher (2003). Max Reger and Karl Straube: Perspectives on an Organ Performing. Routledge. ISBN 9780754630753.

- ^ Adams, David (2007). 'Modern' Organ Style in Karl Straube's Reger Editions (Thesis). University of Amsterdam. hdl:2262/76422.

- ^ Anderson, Christopher S., ed. (2013). Twentieth-Century Organ Music. Routledge. pp. 76–115. ISBN 9781136497896.

- ^ Anderson, Ames (2006b). "Heinrich Fleischer". Choir & Organ. 14 (4).

- ^ Anderson, Ames; Backer, Bruce; Luedtke, Charles (2006). "Nunc Dimmitis, obituary of Heinrich Fleischer". The Diapason. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Schenk, Kathryn Eleanor (1989). Heinrich Fleischer: The Organist's Calling and the Straube Tradition (Thesis). University of Minnesota. p. 134.

- ^ Billmeyer 2018

- ^ Sechter, Simon (1832). "Sebastian Bachs Orgelfugen für das Pianoforte : zu 4 Händen eingerichtet, A-Wn Mus. Hs. 20274". Bach Archive. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Sechter, Simon, ed. (1832). "Sebastian Bachs Orgelfugen für das Pianoforte: zu 4 Händen eingerichtet". Vienna: Haslinger. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "Bach, J.S., Sechs Preludien und Fugen für Orgel (vierh. f. Klav. bearb.)". Berlin: Berlin State Library. 1832. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "D-B Mus.ms. Bach P 925". Bach Archive. 1832. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ Voigt, Carl (1834). Sechs Praeludien und Fugen für die Orgel von Johann Sebastian Bach [BWV 543–548], eingerichtet für das Pianoforte zu vier Händen. Frankfurt am Main: Georg Heinrich Hedler.

- ^ Gleichauf, Franz Xaver (1846). "35. Pianoforte vierhändig, Bach (J. S.)". In Senff, Bartholf (ed.). Jahrbuch für Musik (in German). Expedition der Signale. p. 22.

- ^ Gleichauf, F. X., ed. (1962). Bach Organ Works Transcribed for Piano Duet, 2 Volumes. International Music Company. ASIN B000WMAZIS.

- ^ Stinson 2006, p. 27

- ^ De Rosa, Alessandro (2019). Ernio Morricone: In his own words. Translated by Maurizio Corbella. Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780190681012.

- ^ "Ennio Morricone: 10 (little) things you may not know about the legendary film composer". France Musique. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Billmeyer, Dean (2018). "Straube plays Bach". Rondeau Production. Retrieved 21 October 2020. Introduction to early 20th-century historical performance practice, as prescribed in Karl Straube's 1913 Peters edition of Orgelwerke II (including BWV 543–548). Recorded on Sauer organ in Michaeliskirche, Leipzig.

External links

[edit]- Bach, Johann Sebastian (1825). Sechs Praeludien und sechs Fugen für Orgel oder Pianoforte mit Pedal [BWV 543–548]. Wien: Tobias Haslinger.

- "Prelude and fugue, a BWV 543". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 14 May 2019.

- Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Hawley, Mike (ed.). "Bach/Liszt: The Great Prelude & Fugue in a, BWV 543". MIT. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Score of Liszt's transcription (in various formats).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Prelude and fugue for organ in A minor, BWV 543 at Muziekweb website (recordings)

- BWV 543 (free download of James Kibbie's recording)