Agriculture in Australia

Although Australia is mostly arid, the nation is a major agricultural producer and exporter, with around 421,000 people employed in agriculture, forestry and fishing as of 2023.[1] Agriculture and its closely related sectors earn $155 billion a year for a 12% share of GDP. Farmers and grazers own 135,997 farms, covering 61% of Australia's landmass.[2] Across the country, there is a mix of irrigation and dry-land farming. The success of Australia in becoming a major agricultural power despite the odds is facilitated by its policies of long-term visions and promotion of agricultural reforms that greatly increased the country's agricultural industry.[3]

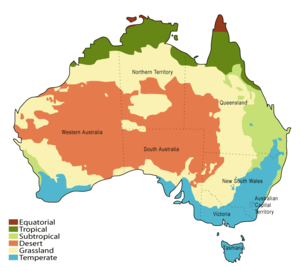

There are three main zones: the high rainfall zone of Tasmania and a narrow coastal zone (used principally for dairying and beef production); wheat, sheep zone (cropping (principally winter crops), and the grazing of sheep (for wool, lamb and mutton) plus beef cattle) and the pastoral zone (characterised by low rainfall, less fertile soils, and large scale pastoral activities involving the grazing of beef cattle and sheep for wool and mutton).[4] An indicator of the viability of agriculture in the state of South Australia is whether the land is within Goyder's Line.

History

[edit]Agriculture in Australia has a lively history. Aboriginal Australians have been variously described as hunter-gatherer-cultivators and proto-farmers, as there is evidence that farming activities were undertaken prior to the arrival of Europeans, including tilling, planting and irrigating. However, these practices were non-industrialised and complementary to hunting, gathering and fishing. Whether the people could be termed agriculturalists is controversial.[5] In 1788, the first European settlers brought agricultural technology from their homelands which radically changed the dominant practices.[6] After some initial failures, wool dominated in the 19th century and, in the first half of the 20th century, dairying increased in its popularity, driven by technological changes like canning and refrigeration.[7]

Meat exports were very significant in the development of Australian agriculture. By 1925, there were 54 export freezing works, capable of killing 6000 cattle and 90,000 sheep and lambs daily. Initially, the meat for British markets had to be frozen, but later beef could be exported chilled.[8]

2000-2019

[edit]

At the turn of the millennium, Australia produced a large variety of primary products for export and domestic consumption. Australia's production in the first five years was as follows:[9]

| Commodity (in millions of AUD$) | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle and calves | 6,617 | 5,849 | 6,345 | 7,331 | 7,082 |

| Wheat | 6,356 | 2,692 | 5,636 | 4,320 | 5,905 |

| Milk | 3,717 | 2,795 | 2,828 | 3,808 | 3,268 |

| Fruit and nuts | 2,333 | 2,408 | 2,350 | 2,640 | 2,795 |

| Vegetables | 2,269 | 2,126 | 2,356 | 2,490 | 2,601 |

| Wool | 2,713 | 3,318 | 2,397 | 2,196 | 2,187 |

| Barley | 1,725 | 984 | 1,750 | 1,240 | 1,744 |

| Poultry | 1,175 | 1,273 | 1,264 | 1,358 | 1,416 |

| Lamb | 1,181 | 1,161 | 1,318 | 1,327 | 1,425 |

| Sugar cane | 989 | 1,019 | 854 | 968 | 1,037 |

Australia's main crops were contrasting in preferred climate: sugar cane (typical of tropical countries), wheat and barley (typical of cold countries).

In 2018, Australia was the world's largest producer of lupin bean (714 thousand tons), the world's second largest producer of chickpeas (1 million tons), the world's fourth largest producer of barley (9.2 million tons) and oats (1.2 million tons), the 5th largest producer of rapeseed (3.9 million tons), the 9th largest producer of sugarcane (33.5 million tons) and wheat (20.9 million tons) and the 13th largest producer of grape (1.66 million tons). In the same year, the country also produced 1.2 million tons of sorghum, 1.1 million tons of potato, in addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products, such as rice (635 thousand tons), maize (387 thousand tons), tomato (386 thousand tons), orange (378 thousand tons), fava beans (377 thousand tons), banana (373 thousand tons), pea (317 thousand tons), carrot (284 thousand tons), onion (278 thousand tons), apple (268 thousand tons), lentils (255 thousand tons), melon (224 thousand tons), watermelon (181 thousand tons), tangerine (138 thousand tons) etc.[10]

2019

[edit]Late in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic began, and Australian agriculture was heavily impacted by the resulting supply chain issues. The scarcity of freight space and disruption to Chinese New Year purchases was particularly painful, with China being Australia's largest export market and a particularly large buyer of live seafood.[11]

China Tariffs

[edit]In May, the Australian government proposed an independent investigation of the origin of COVID-19. Shortly afterwards, China placed large restrictions on their imports of a number of Australian agricultural products, as well as coal. Agriculture is one of Australia's most trade-exposed economic sectors.[12]

Labour shortages

[edit]The agricultural workforce was heavily reliant on international workers, and by the end of 2020, the pandemic resulted in a severe shortage of farm workers across the country. Much produce could not be picked, with losses estimated at $22 million, thanks to a backpacker workforce diminished from 200,000 to 52,000.[13] The shortage lingered through 2021, with skilled labour also in short supply, leading to calls to double Australia's skilled migrant uptake.[14]

Products

[edit]Crops

[edit]

Cereals, oilseeds and grain legumes are produced on a large scale in Australia for human consumption and livestock feed. Wheat is the cereal with the greatest production in terms of area and value to the Australian economy. Sugarcane, grown in tropical Australia, is also an important crop; however, the unsubsidised industry (while lower-cost than heavily subsidised European and American sugar producers) is struggling to compete with the huge and much more efficient Brazilian sugarcane industry.[15]

Horticulture

[edit]

In 2005, McDonald's Australia Ltd announced it would no longer source all its potatoes for fries from Tasmanian producers and announced a new deal with New Zealand suppliers. Subsequently, Vegetable and Potato Growers Australia (Ltd.) launched a political campaign advocating protectionism.[16]

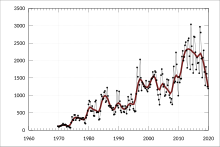

Viticulture

[edit]Although the Australian wine industry enjoyed a large period of growth during the 1990s, overplanting and oversupply led to a large drop in the value of wine, forcing out of business some winemakers, especially those on contracts to large wine-producing companies. At the time, the future for some Australian wine producers seemed uncertain, but by 2015 a national study showed that the industry had recovered and the combined output of grape growing and winemaking were major contributors to the Australian economy's gross output[17] while the associated industry of wine tourism had also expanded.[18] A follow-up report from 2019 demonstrated further consolidation, by which stage wine had become Australia's fifth-largest agricultural export industry, with domestic and international sales contributing AU$45.5 billion to gross output.[19]

Wine producers were impacted by the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season, with Adelaide Hills losing 30% of its vineyards.[20] Grapes around the country were affected by smoke, with the smell affecting the wine produced.

Beef industry

[edit]The beef industry is the largest agricultural enterprise in Australia, and it is the second largest beef exporter, behind Brazil, in the world. All states and territories of Australia support cattle breeding in a wide range of climates. Cattle production is a major industry that covers an area in excess of 200 million hectares. The Australian beef industry is dependent on export markets, with over 60% of Australian beef production exported, primarily to the United States, Korea and Japan.[21]

In southern Australia (NSW, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and south-western Western Australia) beef cattle are often reared on smaller properties as part of a mixed farming or grazing operation, but some properties do specialise in producing cattle. The southern calves are typically reared on pasture and sold as weaners, yearlings or steers at about two years old or older.[22] Artificial insemination and embryo transfer are more commonly used in stud cattle breeding in Australia, but may be used in other herds.[23]

In the Top End, sub-tropical areas and in arid inland regions, cattle are bred on native pastures on expansive cattle stations. Anna Creek Station in South Australia, Australia is the world's largest working cattle station.[24] The North Australian Pastoral Company Pty Limited (NAPCO) is now one of Australia's largest beef cattle producers, with a herd of over 180,000 cattle and fourteen cattle stations in Queensland and the Northern Territory.[25] The Australian Agricultural Company (AA Co) manages a cattle herd of more than 585,000 herd.[26] Heytesbury Beef Pty Ltd owns and manages over 200,000 herd of cattle across eight stations spanning the East Kimberley, Victoria River and Barkly Tablelands regions in Northern Australia.[27]

Prior to European settlement, there were no cattle in Australia. The present herd consists principally of British and European breeds (Bos taurus) in the southern regions, with Aberdeen Angus and Herefords being the most common. In northern Australia, Bos indicus breeds predominate along with their crosses. They were introduced to combine the resistance to cattle ticks and greater tolerance to hot weather.[28]

In 1981, the industry was shaken by the Australian meat substitution scandal, which revealed that horse and kangaroo meat had been both exported overseas and sold domestically as beef.

Dairy

[edit]

Domestic milk markets were heavily regulated until the 1980s, particularly for milk used for domestic fresh milk sales. This protected smaller producers in the northern states who produced exclusively for their local markets. The Kerin Plan (named after politician John Kerin) began the process of deregulation in 1986. The final price supports were removed in 2000 with the assistance of Pat Rowley, head of the Australian Dairy Farmers Federation and the Australian Dairy Industry Council.[29] Deregulation ultimately saw 13,000 Australian dairy farmers produce 10 billion litres of milk in comparison to the 5 billion litres of milk produced by 23,000 farmers prior to deregulation,[30] a 30% reduction in farmers with a 55% rise in milk production.[31] As the Australian dairy industry grows, feedlot systems are becoming more popular.[32][33]

Fisheries

[edit]

The fisheries in Australia is a very large scale industry. Australia produces many species of fish, including farmed, sustainable and intensive, and wild caught such as tuna and other schooling fish.

Seaweeds

[edit]The shorelines, especially the Great Barrier Reef, are providing motivation to help the continent by using seaweed (algae) to absorb nutrients.[34] Because of the giant number of natural Australian seaweeds,[35] not only could seaweed cultivation be used to help absorb nutrients around the GBR and other Australian shores, cultivation could also help feed a large part of the world.[36][37][38] Even the Chinese, who could be considered far more advanced in seaweed cultivation, are interested in the future of Australian seaweeds.[39] Lastly, the GBR itself, because of the delicate corals,[40] has lent itself to utilising seaweed/algae purposely as a nutrient reduction tool in the form of algae.[41]

Olives

[edit]Olives have been grown in Australia since the early 1800s.[42] Olive trees were planted by the warden of the self-funded penal settlement on St Helena Island, Queensland in Moreton Bay.[43] By the mid-90s, there were 2,000 hectares (4,900 acres) of olives, and from 2000 to 2003 passed 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres). By 2014 (Ravetti and Edwards, 2014) there were 2000 plantations, covering over 35,000 hectares (86,000 acres), and producing 93,500 tonnes (92,000 long tons; 103,100 short tons) of olives. 3,000 tonnes (3,000 long tons; 3,300 short tons) were used as table olives and around 5–7,000 tonnes (4.9–6,889.4 long tons; 5.5–7,716.2 short tons) exported to the United States, China, the European Union, New Zealand and Japan. Between 2009 and 2014, Australia imported an average of 31,000 tonnes (31,000 long tons; 34,000 short tons) predominantly from Spain, Italy and Greece.[44] China's olive oil consumption is increasing, and Chinese investors have begun to buy Australian olive farms.[45][46] Olive cultivars include Arbequina, Arecuzzo, Barnea, Barouni, Coratina, Correggiola, Del Morocco, Frantoio, Hojiblanca, Jumbo Kalamata, Kalamata, Koroneiki, Leccino, Manzanillo, Pendulino, Picholine, Picual, Sevillano, UC13A6, and Verdale. Manzanillo, Azapa, Nab Tamri and South Australian Verdale produce table olives.[47]

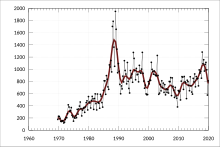

Wool

[edit]Australia is the world's largest producer of wool.[48] The Australian wool industry was worth $3.6 billion in 2022.[49] The total number of sheep is estimated to be 75 million.[48] In the late 1980s, the sheep flock was 180 million.[50] Only 5% of Australia's wool clip is processed onshore.[49] The Merino produces fine wool and was first introduced to Australia in 1797, with the breed being well-suited to the Australian environment.[51] By the 1870s Australia had become the world's greatest wool-growing nation.[52]

Issues facing Australian agriculture

[edit]

Political values

[edit]Historian F.K. Crowley finds that:

- Australian farmers and their spokesman have always considered that life on the land is inherently more virtuous, more healthy, more important and more productive than living in the towns and cities. The farmers complained that something was wrong with an electoral system which produced parliamentarians who spent money beautifying vampire-cities instead of developing the interior.[53]

The Country Party, from the 1920s to the 1970s, promulgated its version of agrarianism, which it called "countrymindedness". The goal was to enhance the status of the graziers (operators of big sheep ranches) and small farmers and justified subsidies for them.[54]

Water management

[edit]

Water management is a major issue in Australia. The nation is struggling with over-allocation issues and increasing variability.[55] Effectively governing such issues has proven to be problematic.[55] Public institutions responsible for water management include the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, which manages water resources in the Murray–Darling basin, Australia's largest river catchment.

Because of Australia's large deserts and irregular rainfall, irrigation is necessary for agriculture in some parts of the country. The total gross value of irrigated agricultural production in 2004-05 was A$9,076 million compared to A$9,618 million in 2000–01. The gross value of irrigated agricultural production represents around a quarter (23%) of the gross value of agricultural commodities produced in Australia in 2004–05, on less than 1% of agricultural land.[56]

Of the 12,191 GL of water consumed by agriculture in 2004–05, dairy farming accounted for 18% (2,276 GL), pasture 16% (1,928 GL), cotton 15% (1,822 GL) and sugar 10% (1,269 GL).[56]

Environmental issues

[edit]In 2006, the CSIRO, the federal government agency for scientific research in Australia, forecast that climate change will cause decreased precipitation over much of Australia and that this will exacerbate existing challenges to water availability and quality for agriculture.[57]

Climate change has damaged farming productivity, reducing broadacre farm profits by an average of 22% since 2000.[58] In 2023, the Department of Agriculture published a National Statement on Climate Change and Agriculture, exploring resilience in the agriculture sector.[59]

Agriculture contributes 13% of Australia's total greenhouse emissions, however, much of this is methane of biological origin, rather than from fossil fuels.[60]

Although native, kangaroos have been known to destroy fences and eat cattle feed, sometimes in problematic numbers.[61]

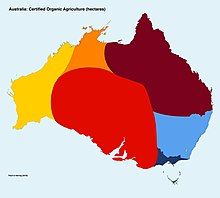

Organic farming

[edit]

As of 2021, $2.3 billion worth of commodities were produced in Australia by the organic agriculture sector, representing approximately 3% of agricultural output.[63] Australia leads the world with 35 million hectares certified organic, which is 8.8% of Australia's agricultural land[62] and Australia now accounts for more than half (51%) of the world's certified organic agriculture hectares.[64]

Genetic modification

[edit]GM grains are widely grown in all states and territories in Australia with the exception of Tasmania, which is the last state to maintain a moratorium against GM.[65] GM crops are regulated under a national scheme by the Gene Technology Regulator, through the Gene Technology Act 2000.[66] As of 2022, there are four GM crops approved to be grown in Australia: cotton, safflower, carnations and canola. In particular, 99.5% of cotton growers in Australia use GM cotton.[67]

Foreign land ownership

[edit]Australia has seen a major increase in foreign ownership of agriculture in the 2010s. According to a report in 2020, it was found that the amount of Australian agricultural land in foreign ownership, increased slightly from 13.4 to 13.8 percent.[68][69][70]

A 2016 Lowy Institute poll found that 87% of respondents were against the Federal Government allowing foreign companies to buy Australian agricultural land a 6% points higher than a similar survey four years ago.[71]

A 2022 ABC's Vote Compass Poll found that 88% of Australians want tighter controls on foreign ownership of farm land, which is an increase from Compass poll results in 2013 and 2016.[72]

Animal welfare and live exports

[edit]Animal welfare has caused public concern, with exports of live animals particularly scrutinised. The practice of exporting live animals has received strong public opposition (a petition carrying 200,000 signatures of people opposed to live export was tabled in parliament[73]) and opposition from the RSPCA because of cruelty.[74]

In 2022, the Labor Party committed to ending live exports of sheep, if elected. In 2023, they commenced the process, however, it is not likely to be completed within the government's first term.[75][76]

In 2006, animal rights organisations including PETA promoted a boycott of Merino wool, as a protest against the practice of mulesing, a procedure used to prevent the animals from becoming fly blown with maggots.[77] In 2004, due to the worldwide attention, AWI proposed to phase out the practice by the end of year 2010; this promise was retracted in 2009.[78]

In 2022, new regulations for chicken welfare were introduced.[79]

Farm safety

[edit]Farming is the most dangerous occupation in Australia. 55 farmers died while working in 2022.[80] Accidents involving tractors accounted for 20 per cent and quad bikes for 14 per cent of deaths.[80]

Information Technology

[edit]Drone technology, Self driver tractors, Online Marketplaces[81] are recent and growing trends. There is little standardisation and no accreditation authorities, though the CSIRO and other independent organisations have evaluated individual developments, the lack of a coordinated approach and lead agency restricts developments and risks Australia's competitiveness.

Public governance

[edit]Before the Federation of Australia in 1901, individual state governments bore responsibility for agriculture. As part of the federation, the Department of Commerce and Agriculture was created to help develop the agricultural industry. The newly created Department of Trade and Customs had additional responsibilities for sugar agreements, as well as cotton.

These responsibilities were merged into a single agricultural department in 1956. Since the merger, the department responsible for agriculture has been renamed and re-structured many times:

- 1956–1974 - Department of Primary Industry

- 1974–1975 - Department of Agriculture

- 1975–1987 - Department of Primary Industry

- 1987–1998 - Department of Primary Industries and Energy

- 1998–2013 - Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

- 2013–2015 - Department of Agriculture

- 2015–2019 - Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

- 2019–2020 - Department of Agriculture

- 2020–2022 - Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment

- 2022– Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

See also

[edit]- Effects of global warming on agriculture in Australia

- History of wheat industry regulation in Australia

- Wheatbelt

- Gardening in Australia

References

[edit]- ^ "Australian Industry, 2022-23 financial year | Australian Bureau of Statistics". www.abs.gov.au. 31 May 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ New reference reveals facts about Australian farming Archived 11 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 30 January 2011

- ^ Pratley, Jim; Rowell, Lewis. "EVOLUTION OF AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURE: FROM CULTIVATION TO NO-TILL" (PDF). Charles Sturt University.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shaw, John H., "Collins Australian Encyclopedia", William Collins Pty Ltd., Sydney, 1984, ISBN 0-00-217315-8

- ^ Keen, Ian (2021). "Foragers or farmers: Dark Emu and the controversy over Aboriginal agriculture" (PDF). Anthropological Forum. 31 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1080/00664677.2020.1861538. S2CID 232765674.

- ^ Faull, Margaret L. (2014). "Indigenous Australian land management before the European settlement in 1788: a review article". Landscape History. 35 (2): 67–79. doi:10.1080/01433768.2014.981396. S2CID 128573674.

- ^ Wickins, Peter (1987). "Pastoral proficiency in nineteenth century South Africa and Australia: A case of cultural determinism?". South African Journal of Economic History. 2 (1): 32–47. doi:10.1080/10113436.1987.10417136.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ "Gross value of farm and fisheries production". Australian Commodities. 13 (2). ABARE economical: 438 and 439. June 2006.

- ^ Australia production in 2018, by FAO

- ^ Pollard, Emma (3 February 2020). "Coronavirus devastates Australian export businesses". ABC News. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "Dollar's decline a mixed blessing". ABC News. 15 May 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Bolton, Meg (11 December 2020). "New lost crop register reveals million-dollar figure the worker shortage is costing Aussie farmers". ABC News. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ May, Natasha (20 October 2021). "Labour shortages may cause farmers to lose crops and consumers to face food price hikes". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Hildebrand, Clive (2002). "Independent Assessment of the Sugar Industry" (PDF). p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ Fair dinkum! Hinch calls 'pointy-head Tasmanian' campaign doomed 1 August 2005, ABC Tasmania, Louise Saunders. Accessed 9 August 2011

- ^ Gillespie, Rob and Michael Clarke. Economic Contribution of the Australian Wine Sector. Report: 18 December 2015. Australian Grape and Wine Authority, 2016. pp. 1, 12-14. Accessible online at [1]. Accessed 7 March 2020.

- ^ Gillespie and Clarke (2015), p. 11.

- ^ Gillespie and Clarke. "Executive Summary." Economic Contribution of the Australian Wine Sector 2019. Report 19 August 2019. Wine Australia, 2019. pp. i-iii.Accessible online at [2]. Accessed 7 March 2020.

- ^ Williams, David (16 February 2020). "How bushfires have hit Australia's winemakers". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Country Leader, 31 January 2011, Farm Facts: Beef is bullish, Rural Press

- ^ "Agriculture - Beef Industry - Australia". Australian Natural Resources Atlas. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Beattie, William A., Beef Cattle Breeding & Management, Popular Books, 1990, ISBN 0-7301-0040-5

- ^ Mercer, Phil (9 June 2008). "Cattle farms lure Australian women". BBC. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ "North Australian Pastoral Company". napco.com.au.

- ^ "AACo". aaco.com.au. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007.

- ^ "Heytesbury Cattle Company". heytesburycattle.com.au.

- ^ Austin, Nigel (1986). Kings of the Cattle Country. Sydney: Bay Books. ISBN 1-86256-066-8.

- ^ Pip Courtney (25 June 2000). Dairy deregulation rolls on despite protests Archived 28 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Landline. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Deregulation: a star turn in milky way". Australian Financial Review. 4 July 2000. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Margetts, D. E. (2007). "National competition policy and the Australian dairy industry". S2CID 157764932.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lush, Deanna (24 April 2003). "SA develops a taste for feedlot systems". stockjournal.com.au. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.dairyaustralia.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Davey, Keith (2000). "Nutrient Absorbers". Life on Australian Seashores. MESA.

- ^ Guiry, M.D. (2015). "Australian Seaweeds". The Seaweed Site.

- ^ "Ideas bloom for seaweed cultivation on the South Coast". 24 June 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Seaweed as Human Food". 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Could seaweed farming be Australia's next aquaculture industry?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 13 January 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Chinese company invests in Aus seaweed, hopes to start farming". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 March 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "The Implications of Climate Change for Australia's Great Barrier Reef". 1988. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Nutrient cycling in the Great Barrier Reef Aquarium". 1988. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Newton, John (13 March 2012). "A Hardy evergreen". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "The remarkable story of the Helena". Treetops Plantation. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Olive growing in Australia" (PDF). Town and Country Farmer. March–April 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Hall, Simon; Stewart, Robb M. (18 February 2014). "China Feeds Rush for Australian Olive Oil". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Sinclair, Hannah (1 September 2017). "Chinese investment in WA olive farm a boost for local workers". Special Broadcasting Service (SBS). Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "A guide to Olive Variety Selection" (PDF). Australian Plants. 1 September 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b Taylor, Tegan (3 April 2018). "Clothing and textile manufacturing's environmental impact and how to shop more ethically". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ a b Prendergast, Joanna (22 November 2022). "Wool industry explores domestic processing to reduce supply chain and trade 'risks'". ABC Rural. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Becker, Joshua (7 December 2020). "Wool has had its ups and downs over 75 years of ABC Rural reporting, but COVID-19 is simply 'weird'". ABC Rural. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "Merino sheep introduced". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Lee, Tim (9 July 2022). "Camden sheep a living link to Australia's modern-day Merino". Landline. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ F.K. Crowley, Modern Australia in Documents: 1901 – 1939 (1973) pp 77-78.

- ^ Rae Wear, "Countrymindedness Revisited," (Australian Political Science Association, 1990) online edition

- ^ a b Ann Wheeler, Sarah; Owens, Katherine; Zuo, Alec. "Is there Public Desire for a Federal Takeover of Water Resource Management in Australia?". Water Research. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2023.120861. hdl:2440/141460. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Drought drives down water consumption". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 November 2006. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ Preston, B.L.; Jones, R.N. (February 2006). "Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions" (PDF). CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ Department of Agriculture (July 2023). "National Statement on Climate Change and Agriculture". Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ Stanley, Michelle; Varischetti (13 July 2023). "Focus on livestock tracing intensifies under new strategy to protect agricultural industry". ABC News. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "Agriculture's contribution to Australia's greenhouse gas emissions". Climate Council. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Hynninen, Eden (12 July 2023). "Farmer reports more than 1,000 kangaroos on property as numbers 'boom' across Victoria". ABC News. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b Paull, John & Hennig, Benjamin (2018) Maps of Organic Agriculture in Australia, Journal of Organics. 5 (1): 29–39.

- ^ "Organic Food". Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Paull, John (2019) Organic Agriculture in Australia: Attaining the Global Majority (51%), Journal of Environment Protection and Sustainable Development, 5(2):70-74.

- ^ "Review Of Tasmania's Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) Moratorium FINAL REPORT" (PDF). 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Office of the Gene Technology Regulator". 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Genetically Modified Crops". 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Kemp, Daniel (23 June 2020). "Foreign ownership of Australian land and water". Agri Investor. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ Tracey, Mollie (28 December 2020). "How much Aussie farmland is foreign owned?". Farm Weekly. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Foreign Ownership of Agricultural Land Report". Australian Taxation Office. Australian Government. 23 June 2020. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ Schwartz, Dominique (20 June 2016). "Foreign farmland ownership poll finds almost nine out of 10 Australians opposed". ABC News. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Few fence-sitters when it comes to foreign ownership of Australian farmland, Vote Compass data shows". ABC News. 5 May 2022.

- ^ "Live Export Petition Exceeds 200,000 Signatures // Animals Australia". AnimalsAustralia.org. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Live Export". Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Wahlquist, Calla; Press, Australian Associated (3 March 2023). "Australia to phase out live sheep export amid opposition from peak farmers body". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Cooper, Lucy (3 June 2022). "Live sheep trade ban won't happen in this term, PM says". ABC News. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ "Pink angers Australian government". BBC News. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 10 January 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Wilkinson, Peter (8 November 2004). "In the News". Australian Wool Growers Association. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ McNaughton, Jane (20 August 2022). "Lives of farmed chickens set to improve under new welfare standards". ABC News. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b Francis, Annabel (29 July 2023). "Farm deaths and injuries return to higher levels with tractors and quad bikes a common cause". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "The Farmers Lot". www.thefarmerslot.com.au. Retrieved 7 September 2023.