Atlantic Revolutions

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Age of Revolution. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2024. |

| Atlantic Revolutions | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Age of Revolution | |

Clockwise from top:

| |

| Date | 22 March 1765 – 4 December 1838 (73 years, 8 months, 1 week and 5 days) |

| Location | |

| Caused by | |

| Resulted in | Multiple revolutions and wars across the Atlantic world, including the American Revolutionary War, French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, and the Spanish American wars of independence |

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

The Atlantic Revolutions (19 April 1775 – 4 December 1838) were numerous revolutions in the Atlantic World in the late 18th and early 19th century. Following the Age of Enlightenment, ideas critical of absolutist monarchies spread. A revolutionary wave occurred, with the aim of ending monarchical rule, emphasizing the ideals of the Enlightenment, and spreading liberalism.

Other revolutions in West Africa emphasized forms of Islam that were egalitarian in comparison to traditional forms.[1]

In 1755, early signs of governmental changes occurred with the formation of the Corsican Republic and Pontiac's War. The largest of these early revolutions was the American Revolution beginning in 1775, which founded the United States.[2] The American Revolution inspired other movements, including the French Revolution in 1789 and the Haitian Revolution in 1791. These revolutions were based on the equivocation of personal freedom with the right to own property — a concept spread by Edmund Burke — and on the equality of all men, an idea expressed in constitutions written as a result of these revolutions.

History

[edit]

It took place in both the Americas and Europe, including the United States (1775–1783), Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1788–1792), France and French-controlled Europe (1789–1814), Haiti (1791–1804), Ireland (1798) and Spanish America (1810–1825).[3] There were smaller upheavals in Switzerland, Russia, and Brazil. The revolutionaries in each country knew of the others and to some degree were inspired by or emulated them.[4]

Independence movements in the New World began with the American Revolution, 1775–1783, in which France, the Netherlands and Spain assisted the new United States of America as it secured independence from Britain. In the 1790s the Haitian Revolution broke out. With Spain tied down in European wars, the mainland Spanish colonies secured independence around 1820.[5]

In long-term perspective, the revolutions were mostly successful. They spread widely the ideals of liberalism, republicanism, the overthrow of aristocracies, kings and established churches. They emphasized the universal ideals of the Enlightenment, such as the equality of all men, including equal justice under law by disinterested courts as opposed to particular justice handed down at the whim of a local noble. They showed that the modern notion of revolution, of starting fresh with a radically new government, could actually work in practice. Revolutionary mentalities were born and continue to flourish to the present day.[7]

The common Atlantic theme breaks down to some extent from reading the works of Edmund Burke. Burke firstly supported the American colonists in 1774 in "On American Taxation", and took the view that their property and other rights were being infringed by the crown without their consent. In apparent contrast, Burke distinguished and deplored the process of the French revolution in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), as in this case property, customary and religious rights were being removed summarily by the revolutionaries and not by the crown. In both cases he was following Montesquieu's theory that the right to own property is an essential element of personal freedom.

The American Revolution, a pivotal event in the broader context of Atlantic revolutions, led to the emergence of the United States as an independent nation. Its ripple effects resonated across the Atlantic, influencing subsequent independence movements and revolutions in Europe and the Americas. For instance, the Haitian Revolution erupted in the 1790s, challenging colonial rule and inspiring aspirations for freedom and equality. Similarly, mainland Spanish colonies secured their independence around 1820 amid the turmoil of European wars. These interconnected revolutions, fueled by ideals of liberalism and republicanism, sought to overthrow entrenched aristocracies and establish governments based on the principles of the Enlightenment. The revolutionary fervor underscored the belief in the possibility of creating radically new governments founded on the principles of justice and equality, a sentiment that continues to resonate in modern times. However, the Atlantic theme of revolution faced complexities and nuances, as highlighted in the contrasting views of figures like Edmund Burke, who supported the American colonists' fight against unjust taxation but criticized the French Revolution for its perceived violation of property and religious rights.

National revolutions

[edit]Europe

[edit]- Corsican Revolution (1755–1769)

- Geneva Revolution (1782)

- Revolt of Dutch Patriots (1785)

- French Revolution (1789–1799)

- Liège Revolution (1789–1795)

- Brabant Revolution (1790)

- Polish War in the Defence of Constitution (1792) and Kościuszko Uprising (1794)

- Serbian Revolution (1804–1835)

- Stäfner Handel in Canton of Zürich, Switzerland (1794–1795)

- Batavian Revolution (1795)

- Scottish Rebellion (1797)

- United Irish Rebellion (1798)

- Helvetic Revolution (1798)

- Altamuran Revolution (1799)

- Norwegian War of Independence (1814)

- Liberal Revolution of 1820 (1820, Portugal)

- Decembrist revolt (1825) and Chernigov Regiment revolt (1825–1826)

Americas

[edit]- Pontiac's War (1763–1766)

- American Revolution (1775–1783)

- Revolt of the Comuneros in New Granada (1781)

- Northwest Indian War (1785–1795)

- Brazilian Revolutionary Movements (1789–1817)

- Minas Conspiracy in Minas Gerais, Brazil (1789)

- Bahian Revolt (Conjuração Baiana) in Bahia, Brazil (1798)

- Pernambucan Revolt in Pernambuco, Brazil (1817)

- Haitian Revolution (1791–1804)

- In the British Virgin Islands, minor slave revolts occurred in 1790, 1823 and 1830.

- Slave revolt in Curaçao (1795)

- Bush War, Saint Lucia (1795)

- Fédon's rebellion, Grenada (1796)

- Second Maroon War, Jamaica (1795–1796)

- Second Carib War, Saint Vincent (1795–1797)

- Spanish American Wars of Independence (1808–1833)

- Independence movements in New Granada

- Colombian War of Independence (1810–1825)

- Venezuelan War of Independence (1810–1823)

- Ecuadorian War of Independence (1810–1822)

- Independence movements in Río de la Plata

- Argentine War of Independence (1810–1818)

- Bolivian War of Independence (1810–1825)

- Independence movements in New Spain

- Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821)

- Independence movements in Peru

- Chilean War of Independence (1810–1826)

- Peruvian War of Independence (1810–1826)

- Independence movements in New Granada

- 1811 German Coast uprising (1811)

- Brazilian War of Independence (1821–1824)

- Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions (1837–1838)

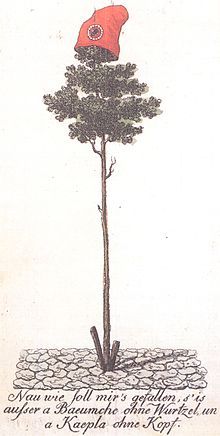

Various connecting threads among these varied uprisings include a concern for the "Rights of Man" and freedom of the individual; an idea (often predicated on John Locke or Jean-Jacques Rousseau) of popular sovereignty; belief in a "social contract", which in turn was often codified in written constitutions; a certain complex of religious convictions often associated with deism and characterized by veneration of reason; abhorrence of feudalism and often of monarchy itself. The Atlantic Revolutions also had many shared symbols, including the name "Patriot" used by so many revolutionary groups; the slogan of "Liberty"; the liberty cap; Lady Liberty or Marianne; the tree of liberty or liberty pole, and so on.

Important individuals during the revolutions

[edit]Important organizations or movements during the revolutions

[edit]See also

[edit]- Age of Revolution

- Atlantic history, on historiography

- Atlantic World

- Piracy in the Atlantic World

- Revolutions of 1848

Notes

[edit]- ^ Getz, Trevor. "READ: West Africa in the Age of Revolutions". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2024-04-19.

- ^ "Timeline of the Revolution". nps.gov.

- ^ Wim Klooster, Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History (2009)

- ^ Laurent Dubois and Richard Rabinowitz, eds. Revolution!: The Atlantic World Reborn (2011)

- ^ Jaime E. Rodríguez O., The Independence of Spanish America (1998)

- ^ Madden, Richard (1843). The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times (30 May 2020 ed.). Belfast: J. Madden & Company. p. 179.

- ^ Robert R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760–1800. (2 vol, 1959–1964)

Further reading

[edit]- Canny, Nicholas, and Philip Morgan, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Atlantic World: 1450–1850 (Oxford UP, 2011).

- Donoghue, John. Fire under the Ashes: An Atlantic History of the English Revolution (U of Chicago Press, 2013).

- Geggus, David P. The Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World (2002)

- Jacques Godechot. France and the Atlantic revolution of the eighteenth century, 1770–1799 (1965)

- Gould, Eliga H. and Peter S. Onuf, eds. Empire and Nation : The American Revolution in the Atlantic World (2004)

- Greene, Jack P., Franklin W. Knight, Virginia Guedea, and Jaime E. Rodríguez O. "AHR Forum: Revolutions in the Americas", American Historical Review (2000) 105#1 92–152. Advanced scholarly essays comparing different revolutions in the New World. in JSTOR

- Israel, Jonathan I.. The Expanding Blaze: How the American Revolution Ignited the World, 1775-1848. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2017. ISBN 978-0-691-17660-4

- Klooster, Wim. Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History (2nd ed. 2018)

- Leonard, A.B. and David Pretel, eds. The Caribbean and the Atlantic World Economy(2018)

- Palmer, Robert. The Age of Democratic Revolutions 2 vols. (1959, 1964)

- Perl-Rosenthal, Nathan. "Atlantic cultures and the age of revolution." William & Mary Quarterly 74.4 (2017): 667–696. online

- Peterson, Mark. "The Cambridge History of Age of Atlantic Revolutions" (2023) pp. 159-541 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108567671.008

- Polasky, Janet L. Revolutions without Borders (Yale UP, 2015). 392 pp. online review

- Potofsky, Allan. "Paris-on-the-Atlantic from the Old Regime to the Revolution." French History 25.1 (2011): 89–107.

- Sepinwall, Alyssa G. "Atlantic Revolutions", in Encyclopedia of the Modern World, ed. Peter Stearns (2008), I: 284 – 289

- Verhoeven, W.M. and Beth Dolan Kautz, eds. Revolutions and Watersheds: Transatlantic Dialogues, 1775–1815 (1999)

- Vidal, Cécile, and Michèle R. Greer. "For a Comprehensive History of the Atlantic World or Histories Connected In and Beyond the Atlantic World?." Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 67#2 (2012). online