Atazanavir

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌætəˈzænəvɪər/ AT-ə-ZAN-ə-veer[1] |

| Trade names | Reyataz, Evotaz, others[2] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603019 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60-68% |

| Protein binding | 86% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 6.5 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal and kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.243.594 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

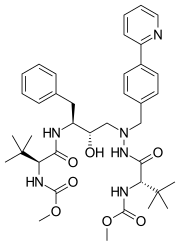

| Formula | C38H52N6O7 |

| Molar mass | 704.869 g·mol−1 |

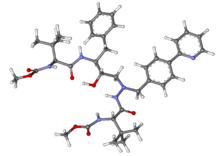

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Atazanavir, sold under the brand name Reyataz among others, is an antiretroviral medication used to treat HIV/AIDS.[2] It is generally recommended for use with other antiretrovirals.[2] It may be used for prevention after a needlestick injury or other potential exposure (postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)).[2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include headache, nausea, yellowish skin, abdominal pain, trouble sleeping, and fever.[2] Severe side effects include rashes such as erythema multiforme and high blood sugar.[2] Atazanavir appears to be safe to use during pregnancy.[2] It is of the protease inhibitor (PI) class and works by blocking HIV protease.[2]

Atazanavir was approved for medical use in the United States in 2003.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[10]

Medical uses

[edit]

Atazanavir is used in the treatment of HIV. The efficacy of atazanavir has been assessed in a number of well-designed trials in ART-naive and ART-experienced adults.[11]

Atazanavir is distinguished from other protease inhibitors in that it has lesser effects on lipid profile and appears to be less likely to cause lipodystrophy. There may be some cross-resistant with other protease inhibitors.[2] When boosted with ritonavir it is equivalent in potency to lopinavir for use in salvage therapy in people with a degree of drug resistance, although boosting with ritonavir reduces the metabolic advantages of atazanavir.[medical citation needed]

Pregnancy

[edit]No evidence of harm has been found among pregnant women taking atazanavir. It is one of the preferred HIV medications to use in pregnant women who have not taken an HIV medication before.[12] It was not associated with any birth defects among over 2,500 live births observed. Atazanavir resulted in a better cholesterol profile and confirmed that it is a safe option during pregnancy.[12]

Contraindications

[edit]Atazanavir is contraindicated in those with previous hypersensitivity (e.g., Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, or toxic skin eruptions). Additionally, atazanavir should not be given with alfuzosin, rifampin, irinotecan, lurasidone, pimozide, triazolam, orally administered midazolam, ergot derivatives, cisapride, St. John's wort, lovastatin, simvastatin, sildenafil, indinavir, or nevirapine.[13]

Atazanavir inhibits the enzyme UDP glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1, thereby impacting the hepatic glucuronidation and elimination of bilirubin.[14] As such atazanavir may not be prescribed to patients with UGT1A1 deficiencies (e.g. those who suffer from Gilbert's syndrome or Crigler–Najjar syndrome) in order to avoid the possibility of jaundice.[14]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common side effects include: nausea, jaundice, rash, headache, abdominal pain, vomiting, insomnia, peripheral neurologic symptoms, dizziness, muscle pain, diarrhea, depression and fever.[13] Bilirubin levels in the blood are normally asymptomatically raised with atazanavir, but can sometimes lead to jaundice.[citation needed]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Atazanavir binds to the active site HIV protease and prevents it from cleaving the pro-form of viral proteins into the working machinery of the virus.[15] If the HIV protease enzyme does not work, the virus is not infectious, and no mature virions are made.[16][17] The azapeptide drug was designed as an analog of the peptide chain substrate that HIV protease would cleave normally into active viral proteins. More specifically, atazanavir is a structural analog of the transition state during which the bond between a phenylalanine and proline is broken.[18][19] Humans do not have any enzymes that break bonds between phenylalanine and proline, so this drug will not target human enzymes.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Atazanavir". MedlinePlus. National Institutes of Health. 15 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Atazanavir Sulfate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Atazanavir (Reyataz) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 27 February 2020. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. 7 July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Reyataz- atazanavir capsule, gelatin coated; Reyataz- atazanavir powder". DailyMed. 7 November 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "Reyataz EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 2 March 2004. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "Teva Announces Exclusive Launch of a Generic Version of Reyataz in the United States" (Press release). Teva. 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2021 – via Business Wire.

- ^ a b "What's New in the Guidelines? | Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Reyataz Package Insert" (PDF). Drugs@FDA. Food and Drug Administration. September 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b Gammal RS, Court MH, Haidar CE, Iwuchukwu OF, Gaur AH, Alvarellos M, et al. (April 2016). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for UGT1A1 and Atazanavir Prescribing". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 99 (4): 363–369. doi:10.1002/cpt.269. PMC 4785051. PMID 26417955.

- ^ "Atazanavir". DrugBank. 9 November 2016. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016.

- ^ Kohl NE, Emini EA, Schleif WA, Davis LJ, Heimbach JC, Dixon RA, et al. (July 1988). "Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 85 (13): 4686–4690. Bibcode:1988PNAS...85.4686K. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. PMC 280500. PMID 3290901.

- ^ Lv Z, Chu Y, Wang Y (2015). "HIV protease inhibitors: a review of molecular selectivity and toxicity". HIV/AIDS. 7: 95–104. doi:10.2147/HIV.S79956. PMC 4396582. PMID 25897264.

- ^ Graziani AL (17 June 2014). "HIV protease inhibitors". UpToDate.

- ^ Bold G, Fässler A, Capraro HG, Cozens R, Klimkait T, Lazdins J, et al. (August 1998). "New aza-dipeptide analogues as potent and orally absorbed HIV-1 protease inhibitors: candidates for clinical development". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 41 (18): 3387–3401. doi:10.1021/jm970873c. PMID 9719591.