NASA Astronaut Group 5

NASA Astronaut Group 5 (nicknamed "The Original Nineteen") was a group of nineteen astronauts selected by NASA in April 1966. Of the six Lunar Module Pilots that walked on the Moon, three came from Group 5. The group as a whole is roughly split between the half who flew to the Moon (nine in all), and the half who flew Skylab and Space Shuttle, providing the core of Shuttle commanders early in that program. This group is also distinctive in being the only time when NASA hired a person into the astronaut corps who had already earned astronaut wings, X-15 pilot Joe Engle. John Young labeled the group the Original Nineteen in parody of the original Mercury Seven astronauts.

Background

[edit]The launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, started a Cold War technological and ideological competition with the United States known as the Space Race. The demonstration of American technological inferiority came as a profound shock to the American public.[1] In response to the Sputnik crisis, although he did not see Sputnik as a grave threat,[2] the President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower, created a new civilian agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), to oversee an American space program.[3] Confidence that the United States was catching up with the Soviet Union was shattered on April 12, 1961, when the Soviet Union launched Vostok 1, and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the Earth. In response, Kennedy announced a far more ambitious goal on May 25, 1961: to put a man on the Moon by the end of the decade.[4] This already had a name: Project Apollo.[5]

By 1966, NASA was looking beyond Project Apollo. On February 3, 1966, the Chief of the Astronaut Office, Mercury Seven astronaut Alan Shepard, created a new branch office at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) called the Advanced Programs Office. NASA announced plans for the future on March 3. The Apollo Applications Program (AAP), as it was named in September 1965, was extremely ambitious in scope. It called for no less than 45 crewed missions, utilizing 19 Saturn V and 26 Saturn IB rockets. There would be three orbital workshops, three orbital laboratories and four Apollo Telescope Mounts. The first AAP launch was expected to occur as early as April 1968 if the Moon landing went well. Each orbital laboratory was expected to be visited by two or three crews. At this point, NASA had 33 astronauts. The Director of Flight Crew Operations, Mercury Seven astronaut Deke Slayton, reckoned that NASA needed another two dozen trained astronauts for AAP.[6][7] On September 10, 1965, NASA announced that it was recruiting more pilot astronauts.[8]

Selection

[edit]Key selection criteria were that candidates:

- Be a United States citizen;

- Born on or after December 1, 1929;

- 6 feet 0 inches (1.83 m) or less in height;

- With a bachelor's degree in the physical or biological sciences, or engineering; and

- Either a graduate of an armed force test pilot school or with 1,000 hours of jet flying experience.[8]

In addition, all applicants had to be able to pass a class I flight physical examination, which required 20–20 uncorrected vision.[8] The height requirement was firm, an artifact of the size of the Apollo spacecraft.[9] The criteria were much the same as those for NASA Astronaut Group 3 in 1963, except that the age requirement was raised from 34 to 36 years of age.[10] Active-duty military applicants had to apply through their respective services. Civilian applicants and military reservists could apply directly. They had to fill in a Civil Service Form 57 Application for Federal Employment, which could be obtained from U.S. Post Offices, and mail it to Pilot-Astronaut, P.O. Box 2201, Houston, Texas. Applications had to be received postmarked by midnight December 1, 1965.[8]

About 5,000 applications were received by the deadline.[11] Of these, only 351 met the key criteria. From this group, 159 applicants, 100 of whom were military and 59 were civilians, were selected for further consideration.[12] Six women had applied, but none apparently met the key criteria, most likely because women were not allowed to fly military jet aircraft in the United States at this time. Lieutenant Frank K. Ellis, a U.S. Navy aviator who had lost both legs in an air crash in July 1962, submitted an application, arguing that being a double amputee would not be a handicap in space. NASA was impressed with his tenacity, but he too was passed over.[11] Michael Collins later recalled that while he felt a sense of relief at there being no female finalists, he was disturbed that there were no African-American ones.[13]

From this 159, 44 were selected to undergo medical examinations at Brooks Air Force Base at San Antonio, Texas. These were conducted between January 7 and February 15, 1966. Several had been through the NASA astronaut selection process before. Edward Givens was applying for the second time, having previously applied for NASA Astronaut Group 1 in 1959. Jack Swigert was applying for the third time, having previously applied for NASA Astronaut Group 2 in 1962 and NASA Astronaut Group 3 in 1963. Vance Brand, Ron Evans, Jim Irwin and Don Lind had also applied in 1963, and Lind had applied for NASA Astronaut Group 4 as a scientist-astronaut in 1965, but had been rejected as too old. Psychological tests included Rorschach tests; physical tests included encephalograms, and sessions on treadmills and a centrifuge. Other tests included some that Lind thought had been originated by the Inquisition, such as plunging a hand into hot water and having cold water poured into the ears.[14]

The final stage of the selection process was an interview by the seven-member selection panel. This was chaired by Deke Slayton, with the other members being astronauts Alan Shepard, John Young, Michael Collins and C. C. Williams, NASA test pilot Warren North, and spacecraft designer Max Faget. Interviews were conducted over a week at the Rice Hotel. A point system that Slayton had devised for previous selections was used. Each candidate was given a score out of 30. Ten points were for "academics". This was broken down into one point for IQ, four for academic degrees and qualifications, three for NASA aptitude tests, and two for the results of a technical interview. Ten points were for "pilot performance", which were broken down into three points for flying record, a point for a test pilot rating, and six points for a technical interview. The remaining ten points were for "character and motivation". Thus, eighteen of the thirty points were awarded for the interview, which took about an hour for each of the candidates. The selection panel then met at Rice University to review their findings.[15][16]

When the scores were tallied, Fred Haise came out with the highest score. In all, 19 candidates were rated as qualified. Young and Collins were shocked when Slayton said that he would take all 19.[16] A reason for the larger-than-expected cohort was that the astronaut corps' attrition rate was double the 10% NASA had expected, including the deaths in February of Elliot M. See and Charles Bassett in the 1966 NASA T-38 crash.[17] Selection occurred at the same time as for the second group of Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) astronauts, with many applying to both programs. Successful candidates were told that NASA or MOL chose them, with no explanation.[18]

Group members

[edit]| Image | Name | Born | Died | Career | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

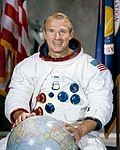

Vance D. Brand | Longmont, Colorado, May 9, 1931 |

Brand received a Bachelor of Science degree in business from the University of Colorado in 1953. He then served in the United States Marine Corps (USMC), first as an infantry officer, and then, from 1955, as an aviator. He was separated from the USMC in 1957, but continued to serve in United States Marine Corps Reserve and Air National Guard jet fighter squadrons until 1964, reaching the rank of major. He returned to the University of Colorado, where he earned a second Bachelor of Science degree, this time in aeronautical engineering, in 1960, and joined Lockheed Corporation as a flight test engineer. Lockheed sent him to the United States Naval Test Pilot School in Patuxent River, Maryland, where he qualified as a test pilot with Class 33 in February 1963. He earned a Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1964. Brand was backup command module pilot for Apollo 15, backup commander for Skylab 3 and Skylab 4, and commander of the unflown Skylab Rescue mission. In July 1975, he flew in space for the first time as command module pilot of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first joint US/Soviet Union space mission. Later he commanded STS-5 in the Space Shuttle Columbia in November 1982, STS-41-B in the Space Shuttle Challenger in February 1984, and STS-35 in the Space Shuttle Columbia in December 1990. He left the Astronaut Office in 1992 to become Chief of Plans at the National Aerospace Plane (NASP) Joint Program Office at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. In September 1994, he became the Assistant Chief of Flight Operations at the Dryden Flight Research Center, where he subsequently became Acting Chief Engineer, deputy director for Aerospace Projects, and finally Acting Associate Center Director for Programs. He retired from NASA in January 2008. | [19][20] | |

|

John S. Bull | Memphis, Tennessee, September 25, 1934 |

August 11, 2008 | Bull received a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from Rice University in 1957. He completed a year of his master's degree before joining the United States Navy (USN) in June 1957. He qualified as a naval aviator the following year. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School in Patuxent River, Maryland, in February 1964. He never flew in space; he resigned from the astronaut corps in 1968 after learning that he was suffering from pulmonary disease. He entered Stanford University, where he earned a Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering in 1971, and then a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in 1973. He worked at the NASA Ames Research Center from 1973 to 1985. | [21][22] |

|

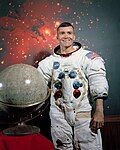

Gerald P. Carr | Denver, Colorado, August 22, 1932 |

August 26, 2020 | Carr joined the United States Navy in 1949. In 1950, he was appointed a midshipman (NROTC), and entered the University of Southern California, from which he received a Bachelor of Engineering degree in mechanical engineering in 1954. On graduation, he was commissioned in the USMC, and then qualified as an aviator. He received a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1961, and a Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from Princeton University the following year. He served as a member of the astronaut support crews and as CAPCOM for the Apollo 8 and Apollo 12 flights, and was involved in the development and testing of the Lunar Roving Vehicle. He was in the likely crew rotation position to serve as lunar module pilot for Apollo 19 before this mission was canceled by NASA in 1970. Between November 1973 and February 1974, he commanded Skylab 4, spending over 2,017 hours in space, including 15 hours and 48 minutes in three EVAs outside the Skylab space station. He retired from the USMC in September 1975, and from NASA in June 1977. | [23][24][25] |

|

Charles M. Duke Jr. | Charlotte, North Carolina, October 3, 1935 |

Duke received a Bachelor of Science degree in naval sciences from the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, 1957, and was commissioned as an officer in the United States Air Force (USAF). He earned a Master of Science degree in aeronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1964, and qualified as a test pilot at the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (class 64-C) in September 1965. He served as a member of the astronaut support crew of Apollo 10; was CAPCOM for the Apollo 11 Moon landing; and backup Lunar Module pilot on Apollo 13. In April 1972, as Lunar Module pilot of Apollo 16, he became the tenth person to walk on the Moon. He was also backup Lunar Module pilot on Apollo 17. He retired from NASA in 1975. | [26][27] | |

|

Joe H. Engle | Dickinson County, Kansas, August 26, 1932 |

July 10, 2024 | Engle received a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Kansas in 1955. He received a USAF commission through the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (AFROTC) program there. In April 1962 he qualified as a test pilot at the USAF Test Pilot School (Class 61-C), and then attended the Aerospace Research Pilot School (Class III), from which he graduated in May 1963. The following month he was assigned as one of two USAF test pilots to fly the X-15. On June 29, 1965, he flew the X-15 to an altitude of 280,600 feet (85,500 m), and became the youngest pilot ever to qualify as an astronaut. Three of his sixteen X-15 flights exceeded the 50-mile (260,000 ft; 80,000 m) altitude required for a USAF astronaut rating. He served as a member of the support crew for the Apollo 10 mission, was the back-up Lunar Module pilot for the Apollo 14 mission, and was scheduled to fly to and walk on the Moon with Apollo 17, but was replaced by geologist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt so that a geologist could visit the Moon on the last Apollo Moon mission after Apollo 18 was canceled. He commanded the Space Shuttle Enterprise in the Approach and Landing Tests in February through October 1977, and was commander of the STS-2 mission in the Columbia in November 1981 and the STS-51-I mission in the Space Shuttle Discovery in August 1985. He served as Deputy Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight at NASA Headquarters from March to December 1982, and was the Air National Guard Assistant to the Commander in Chief, United States Space Command and North American Air Defense Command (NORAD). He retired from NASA and the USAF in November 1986. | [28][29][30] |

|

Ronald E. Evans Jr. | St. Francis, Kansas, November 10, 1933 |

April 7, 1990 | Evans received a Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering from the University of Kansas in 1956, and received a commission in the USN through the NROTC program there. He qualified as a naval aviator. He earned a Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1964. He was a member of the astronaut support crews for the Apollo 7 and Apollo 11 missions, and was backup command module pilot of Apollo 14. In December 1972, he flew to the Moon as command module pilot of Apollo 17, the last Apollo lunar landing mission. He was later backup command module pilot for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) mission. He retired from the USN in 1976, and from NASA the following year. | [31] |

|

Edward G. Givens Jr. | Quanah, Texas, January 5, 1930 |

June 6, 1967 | Givens received a Bachelor of Science degree in naval science from the U. S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1952. He was commissioned into the USAF, and qualified as a pilot. In October 1958 he qualified as a test pilot at the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (Class 58-D), and attended the Aerospace Research Pilot School (Class III), from which he graduated in May 1963. He served on the Apollo 7 support crew, but never flew in space as he was killed in an automobile accident in 1967. | [32][33] |

|

Fred W. Haise Jr. | Biloxi, Mississippi, November 14, 1933 |

Haise joined the Naval Air Cadet program during the Korean War to avoid the draft. He qualified as a naval aviator in 1954, and elected to accept a commission in the USMC. He was separated from the USMC in September 1956, and entered the University of Oklahoma. While there, he joined the Oklahoma Air National Guard. He received his Bachelor of Science degree with honors in 1959, and took a job as a research pilot at NASA's Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, transferring to the Ohio National Guard. After being called to active duty during the Berlin crisis, he was posted to the NASA Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California. In 1965 he qualified as a test pilot at the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (Class 64-A). He served as backup lunar module pilot for the Apollo 8 and 11 missions, and flew to the Moon as Lunar Module pilot of the Apollo 13 mission. He would have been the sixth person to walk on the Moon, but the lunar landing was aborted. He later served as backup spacecraft commander for the Apollo 16 mission, and was slated to walk on the Moon as commander of Apollo 19, but that mission was canceled. From April 1973 to January 1976, he was technical assistant to the manager of the Space Shuttle Orbiter Project. He commanded the Space Shuttle Enterprise in the Approach and Landing Tests between February and October 1977, but never flew it in space, as he retired from NASA in 1979. | [25][34][35] | |

|

James B. Irwin | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, March 17, 1930 |

August 8, 1991 | Irwin received a Bachelor of Science degree in naval science from the United States Naval Academy in 1951. He was commissioned in the USAF, and qualified as a pilot. He earned Master of Science degrees in aeronautical engineering and instrumentation engineering from the University of Michigan in 1957. He graduated from the USAF Experimental Test Pilot School (class 60-C) in 1961, and the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School (Class IV) in 1963. He was a member of the astronaut support crew for Apollo 10, and the backup lunar module pilot for Apollo 12. In July 1971, as the lunar module pilot of Apollo 15, he became the eighth person to walk on the Moon. He retired from NASA and the USAF in July 1972. | [36][37] |

|

Don L. Lind | Midvale, Utah, May 18, 1930 | August 30, 2022 | Lind received a Bachelor of Science degree with honors in physics from the University of Utah in 1953. The following year he enlisted in the USN, and was commissioned through its Officer Candidate School at Newport, Rhode Island. He left active duty in 1957, although he remained in the United States Navy Reserve until 1969. He worked at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, and was awarded his PhD in high energy nuclear physics from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1964. He then joined NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. He was backup pilot for Skylab 3 and Skylab 4 and the unflown Skylab Rescue mission. His only space flight was as mission specialist of STS-51-B in April 1985 aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger, nineteen years after being selected as an astronaut. He retired from NASA in 1986. | [38][39] |

|

Jack R. Lousma | Grand Rapids, Michigan, February 29, 1936 |

Lousma received a Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from the University of Michigan in 1959. He enlisted in the USMC, and was commissioned through its Officer Candidates School at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia. He earned a Master of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1965. He served as a member of the astronaut support crews for the Apollo 9, 10, and 13 missions, and flew in space from July to September 1973 as command module pilot of Skylab 3, the second crew of the Skylab space station. He was also backup docking module pilot for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project mission in July 1975. In March 1982, he commanded the STS-3 mission in the Space Shuttle Columbia. He retired from NASA and the USMC in 1983. | [40][41] | |

|

T. Kenneth Mattingly, II | Chicago, Illinois, March 17, 1936 |

October 31, 2023 | Mattingly received a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from Auburn University in 1958, and was commissioned in the USN through its NROTC program. He graduated from the USAF Experimental Test Pilot School (class 65-B) and the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School in 1966. He served as a member of the support crews for the Apollo 8 and 11 missions, and was the prime command module pilot for Apollo 13, but was removed from flight status 72 hours prior to the scheduled launch due to exposure to rubella, which he was not immune to. He flew in space as command module pilot of Apollo 16 in April 1972. From January 1973 to March 1978, he was the head of the Astronaut Office support for the STS (Shuttle Transportation System) program. He then became the technical assistant for flight test to the manager of the Orbital Flight Test Program. From December 1979 to April 1981, he headed the Astronaut Office ascent/entry group. He was backup commander for STS-2 and STS-3, second and third orbital test flights of the Space Shuttle Columbia. He flew in space again in June 1982 as commander of STS-4, which carried a classified United States Department of Defense (DOD) payload, in Columbia. From June 1983 until May 1984, he was with the Astronaut Office DOD Support Group. In January 1985 he commanded STS-51-C, the first classified United States Department of Defense mission, in the Space Shuttle Discovery. He retired from NASA and the USN in 1985. | [42][43][44][45] |

|

Bruce McCandless II | Boston, Massachusetts, June 8, 1937 |

December 21, 2017 | McCandless received a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy in 1958, and became a naval aviator. He earned a Master of Science degree in Electrical Engineering from Stanford University in 1965, and a Master of Business Administration degree from the University of Houston-Clear Lake in 1987. He was a member of the support crew for the Apollo 14 mission, a CAPCOM on the Apollo 10, 11 and 14 missions, and backup command module pilot for Skylab 2, the first crewed Skylab mission. In February 1984, he flew in space for the first time as a mission specialist on the STS-41-B mission in the Space Shuttle Challenger, during which he conducted the first untethered EVA. In April 1990, he flew as a mission specialist on the Space Shuttle Discovery on the STS-31 mission which deployed the Hubble Space Telescope. He retired from NASA and the USN in August 1990. | [46][47][48][49] |

|

Edgar D. Mitchell | Hereford, Texas, September 17, 1930 |

February 4, 2016 | Mitchell received a Bachelor of Science degree in industrial management from Carnegie Mellon University in 1952. He enlisted in the USN, and was commissioned through its Officer Candidate School at Newport, Rhode Island. He received a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1961. He also earned a doctorate of science degree in aeronautics and astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1964. From 1964 to 1965 he was chief of the Project Management Division of the Navy Field Office for Manned Orbiting Laboratory. He graduated from the USAF Experimental Test Pilot School (class 65-B) and the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School in 1966. He served as a member of the support crew for Apollo 9, and as backup Lunar Module pilot for Apollo 10. As Lunar Module pilot of Apollo 14 in January 1971, he became the sixth person to walk on the Moon. He retired from NASA and the USN in 1972. | [50][51] |

|

William R. Pogue | Okemah, Oklahoma, January 23, 1930 |

March 3, 2014 | Pogue received a Bachelor of Science degree in education from Oklahoma Baptist University in 1951. He enlisted in the USAF, where he was trained as a pilot, and commissioned as a second lieutenant on October 25, 1952. He flew 43 combat missions in the Korean War. He was a member of the U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds from 1955 to 1957. He entered Oklahoma State University, where he earned a Master of Science degree in mathematics in 1960. He qualified as a test pilot at the Empire Test Pilots' School (ETPS) in England, and then became an instructor at the Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS). He served as a member of the support crews for the Apollo 7, 11, 13 and 14 missions. Between November 1973 and February 1974, he was the command module pilot of the 84-day Skylab 4 mission. He retired from NASA and the USAF in September 1975. | [52][53][54][49] |

|

Stuart A. Roosa | Durango, Colorado, August 16, 1933 |

December 12, 1994 | Roosa worked for the U.S. Forest Service as a smokejumper, dropping into at least four active fires in Oregon and California during the 1953 fire season. He joined the USAF in December 1953 and was commissioned through the Aviation Cadet Program at Williams Air Force Base, Arizona, where he received his flight training. He received a Bachelor of Science degree with honors in aeronautical engineering from the University of Colorado in 1960 under the Air Force Institute of Technology program, and qualified as a test pilot at the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (class 64-C) in September 1965. He was a member of the support crew for Apollo 9, and flew to the Moon as command module pilot of Apollo 14 in January and February 1971. He served as backup command module pilot for the Apollo 16 and 17 missions, and was assigned to the Space Shuttle program until his retirement from NASA and the USAF in 1976. | [55][56] |

|

John L. Swigert Jr. | Denver, Colorado, August 30, 1931 |

December 27, 1982 | Swigert received a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Colorado in 1953. He served as a fighter pilot with the USAF from 1953 to 1956. After leaving active duty he served with Massachusetts Air National Guard from September 1957 to March 1960, and then with the Connecticut Air National Guard from April 1960 to October 1965. He earned a Master of Science degree in aerospace science from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1965, and a Master of Business Administration degree from the University of Hartford in 1967. He served as a member of the support crew for the Apollo 7 mission, and was assigned to the Apollo 13 backup crew. He replaced prime crewman Thomas K. Mattingly as command module pilot 72 hours before the launch of the mission after Mattingly was exposed to rubella, and flew the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission in April 1970. He was designated as command module pilot on Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, but was replaced by Brand because of the Apollo 15 postal covers incident. He resigned from NASA in August 1977 to enter politics. In November 1982 he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, but died of bone cancer on December 28, 1982, before he could be sworn in. | [57] |

|

Paul J. Weitz | Erie, Pennsylvania, July 25, 1932 |

October 22, 2017 | Weitz received a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from Pennsylvania State University in 1954, and joined the USN through its NROTC program. He earned a master's degree in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, in 1964, and flew 132 combat missions over Vietnam. He was command module pilot of Skylab 2, the first crewed Skylab mission, in May and June 1973. In April 1983, he commanded STS-6, the maiden flight of the Space Shuttle Challenger. He was deputy director of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, when he retired from NASA in May 1994. | [12][58][59] |

|

Alfred M. Worden | Jackson, Michigan, February 7, 1932 |

March 18, 2020 | Worden received a Bachelor of Military Science degree from the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1955. He joined the USAF, and became a fighter pilot. He earned Master of Science degrees in astronautical/aeronautical engineering and instrumentation engineering from the University of Michigan in 1963. He qualified as a test pilot at the Empire Test Pilots' School (ETPS) in England and then at the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (class 64-C) in September 1965. He served as a member of the support crew for Apollo 9, and as backup command module pilot for Apollo 12. In July and August 1971 he flew to the Moon as command module pilot of Apollo 15. He was Senior Aerospace Scientist at the NASA Ames Research Center from 1972 to 1973, and chief of the Systems Study Division at Ames from 1973 to 1975, when he retired from NASA and the USAF. | [60] |

Demographics

[edit]| Year of selection | 1959 | 1962 | 1963 | 1966 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number selected | 7 | 9 | 14 | 19 |

| Average age | 34.5 | 32.5 | 30.0 | 32.8 |

| Average college years | 4.3 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 5.8 |

| Average flying hours | 3,500 | 2,800 | 2,315 | 2,714 |

| Average jet flying hours | 1,700 | 1,900 | 1,800 | 1,925 |

John Young labeled the group the "Original Nineteen" in parody of the original Mercury Seven astronauts.[62] Of the nineteen, four were civilians: Brand, Haise, Lind and Swigert. Seven were from the USAF: Majors Givens, Irwin and Pogue, and Captains Duke, Engle, Roosa and Worden. Six were from the Navy: Lieutenant Commander Evans, Mitchell and Weitz, and Lieutenants Bull, Mattingly and McCandless. There were two marines, Major Carr and Captain Lousma. Swigert and Mattingly were single; all the rest were married with children. Carr had the most children, with six, followed by Lind with five, and Brand and Roosa, who had four. All were male and white. They were slightly older than the 1963 group, and this translated into more flying hours. Twelve were test pilots: Brand, Bull, Duke, Engle, Givens, Haise, Irwin, Mattingly, Mitchell, Pogue, Roosa and Worden. They also had more education than previous groups. Lind and Mitchell had doctorates, and Brand, Carr, Duke, Evans, Lousma, McCandless, Pogue, Swigert, Weitz and Worden had master's degrees.[12] Engle had already earned his USAF astronaut wings flying the X-15, and Duke, Engle, Givens, Haise, Irwin, Mattingly, Mitchell, Roosa and Worden had received some astronaut training through the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS).[63]

Training

[edit]The selection of the nineteen was publicly announced on April 4, 1966.[10] Seventeen of the nineteen faced the media for the first time at a press conference at the MSC News Center; Givens was still involved in USAF work, and Carr was recovering from a case of measles. On May 9, they commenced fifteen months of formal astronaut training. They were joined by Joseph Kerwin and Curt Michel from NASA Astronaut Group 4, who were qualified military pilots; the remaining three members of that group joined after they completed flight training in August. Together, the 24 new astronauts were the most that NASA had ever trained at the one time, although they would be surpassed by some of the later groups. The first order of business was checking out all the pilots on the aircraft that they would have to fly, the Lockheed T-33 and the Northrop T-38.[64]

Training was conducted on Monday to Wednesday, with Thursday and Friday for field trips. They were given classroom instruction in astronomy (15 hours), aerodynamics (8 hours), rocket propulsion (8 hours), communications (10 hours), space medicine (17 hours), meteorology (4 hours), upper atmospheric physics (12 hours), navigation (34 hours), orbital mechanics (23 hours), computers (8 hours) and geology (112 hours). The training in geology included field trips to the Grand Canyon and the Meteor Crater in Arizona, Philmont Scout Ranch in New Mexico, Horse Lava Tube System in Bend, Oregon, and the ash flow in the Marathon Uplift in Texas, and other locations, including Alaska and Hawaii.[65] There was also jungle survival training in Panama, and desert survival training around Reno, Nevada. Water survival training was conducted at Naval Air Station Pensacola using the Dilbert Dunker.[66] Some 30 hours of briefings were conducted on the Apollo command and service module, and twelve on the Apollo Lunar Module.[67]

Operations

[edit]

Although training continued until September 1967,[68] Shepard assigned them to six branches of his office on October 3, 1966. Engle, Lousma, Pogue and Weitz were assigned to the Apollo Applications Branch, which was headed by Group 3 member Alan Bean, with Bill Anders as his deputy. Brand, Evans, Mattingly, Swigert and Worden were assigned to the CSM Block II Branch, which was headed by Group 2 member Pete Conrad, with Group 3 member Richard Gordon as his deputy. Bull, Carr, Haise, Irwin and Mitchell were assigned to Group 2 member Neil Armstrong's LM/LLRV/LLRF Branch. Givens was assigned to John Young's Pressure Suits/PLSS Branch; Lind and McCandless were to Owen Garriott's Experiments Branch; and Duke and Roosa to Frank Borman and C.C. Williams's Boosters/Flight Safety Panels Branch.[69]

In earlier groups, the senior astronaut had assumed the role of command module pilot while the more junior was the lunar module pilot, but the Nineteen were divided into CSM and LM specialists. Slayton asked each of the Nineteen which speciality he preferred, but made the final decision himself. This early division of assignments would have a profound effect on their subsequent careers. Brand, Evans, Givens, Mattingly, Pogue, Roosa, Swigert, Weitz and Worden became CSM specialists, while Bull, Carr, Duke, Engle, Haise, Irwin, Lind, Lousma, McCandless and Mitchell became LM specialists.[70]

During Projects Mercury and Gemini, each mission had a prime and a backup crew. For Apollo, a third crew of astronauts was added, known as the support crew. The support crew maintained the flight plan, checklists, and mission ground rules, and ensured that the prime and backup crews were apprised of any changes. The support crew developed procedures in the simulators, especially those for emergency situations, so that the prime and backup crews could practice and master them in their simulator training.[71]

Support crew assignments soon became the stepping stone to assignment to a backup, and then a prime crew. For the Apollo 1, which would not carry a LM, the support crew three CSM specialists were assigned to the support crew: Givens, Evans and Swigert. For Apollo 2, which would test the LM, two LM specialists, Haise and Mitchell, were assigned to the support crew, along with Worden, a CSM specialist. For Apollo 3, the support crew consisted of LM specialists Bull and Carr, and CSM specialist Mattingly.[72] The schedule was disrupted by the deaths of Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee in the Apollo 1 fire on January 27, 1967,[73] Givens in a car crash on June 6,[74] and C.C. Williams in an air crash on October 5.[75] Pogue replaced Givens on the first support crew, which now supported Apollo 7.[76]

Haise became the first of the Nineteen to be promoted to a backup crew assignment when he joined Armstrong's backup crew for the Apollo 9 mission, followed by Mitchell, who joined Gordon Cooper's backup crew for Apollo 10. They were replaced by Lousma and Roosa, respectively, while Brand replaced Bull, who had been forced to resign due to ill-health. Apollo 8 and 9 subsequently exchanged prime, backup and support crews, so Brand, Carr and Mattingly became the support crew of Apollo 8, and Lousma, Roosa and Worden became that of Apollo 9.[77] Originally, Mitchell was in line to be the first member of the group to fly in space, but due to the swap of Apollo 13 and Apollo 14 crews, Swigert and Haise became the first. Starting with Apollo 13, each crew consisted of a senior astronaut from Group 1, 2 or 3, and a CM and LM specialist from the Nineteen,[78] except that geologist Harrison Schmitt from Group 4 was designated as the Lunar Module pilot of Apollo 18, and then took Engle's place on Apollo 17 when Apollo 18 was canceled.[79]

Of the 24 men who flew to the Moon on Apollo missions, nine were from the Nineteen, the most of any group. Three of them—Mitchell, Irwin and Duke—walked on the Moon, and Worden, Mattingly and Evans conducted deep space EVAs on the way back from the Moon. Four more of the Nineteen flew on the three Skylab missions, and also performed EVAs.[80] Brand flew as command module pilot on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975, becoming the last of the Nineteen to fly in an Apollo spacecraft.[81]

With no more space flights in prospect, ten of the Nineteen left NASA in the 1970s. The seven that remained would all fly Space Shuttle missions.[80] Veteran astronauts Engle, Lousma, Mattingly, Brand and Weitz commanded STS-2, STS-3, STS-4, STS-5 and STS-6 respectively.[19][28][40][42][58] McCandless was the only one of the Nineteen to perform an EVA from a shuttle,[80] which he did as a mission specialist on his first space flight, the STS-41B mission in February 1984.[46] Lind had to wait even longer; flying in space for the first time as a mission specialist on STS-51B in April and May 1985, nineteen years after he was first selected as an astronaut in April 1966, and fifteen after Haise and Swigert had become the first of the Nineteen to fly on Apollo 13 in April 1970.[82] The last mission flown by any of the Nineteen was STS-35 in December 1990, which was commanded by Brand,[83] who became the last member of the group to leave the Astronaut Office when he departed in 1992. Between them, the Nineteen had flown 29 Space Shuttle missions.[80]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 28–29, 37.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 56.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 82.

- ^ Burgess 2013, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood & Swenson 1979, p. 15.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. xxvii, 10.

- ^ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 172.

- ^ a b c d "NASA Recruiting Additional Pilot-Astronauts" (PDF). NASA Roundup. Vol. 24, no. 4. September 10, 1965. p. 1. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 12.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d "Newly-Selected Group of 19 Astronauts" (PDF). NASA Roundup. Vol. 5, no. 13. April 15, 1966. pp. 4–5. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ Collins 2001, p. 178.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Collins 2001, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Thompson, Ronald (April 5, 1966). "19 New Spacemen Are Named". The High Point Enterprise. High Point, North Carolina. p. 2A – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Homer 2019, p. 35.

- ^ a b NASA (April 2008). "Astronaut Bio: V.D. Brand". Archived from the original on April 22, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 33.

- ^ NASA (December 1993). "Astronaut Bio: John S. Bull". Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 34.

- ^ NASA (October 2003). "Astronaut Bio: Gerald P. Carr". Archived from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Orloff 2000, pp. 33, 112.

- ^ a b "Apollo 18 through 20 – The Cancelled Missions". NSSDC. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ^ NASA (December 1994). "Astronaut Bio: Charles Duke". Archived from the original on December 17, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 38–40.

- ^ a b NASA (March 1987). "Astronaut Bio: Joe Henry Engle". Archived from the original on September 22, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Recer, Paul (December 2, 1986). "Senior NASA astronaut Joe H. Engle retires". AP. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 40–42.

- ^ NASA (April 1990). "Astronaut Bio: Ronald E. Evans". Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ NASA (June 1967). "Astronaut Bio: Edward G. Givens". Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 45–47.

- ^ NASA (January 1996). "Astronaut Bio: Fred Haise". Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 47–49.

- ^ NASA (August 1972). "Astronaut Bio: James Irwin". Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 49–51, 216.

- ^ NASA (January 1987). "Astronaut Bio: Don Lind". Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b NASA (February 1999). "Astronaut Bio: Jack Robert Lousma". Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b NASA (January 1987). "Astronaut Bio: Thomas K. Mattingly II". Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (November 2, 2023). "Ken Mattingly, Astronaut Scrubbed From Apollo 13, Is Dead at 87". The New York Times.

- ^ Donaldson, Abbey (November 2, 2023). "NASA Administrator Remembers Apollo Astronaut Thomas K. Mattingly II" (Press release). NASA.

- ^ a b NASA (May 1990). "Astronaut Bio: Bruce McCandless II". Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ "Astronaut Bruce McCandless, the first person to fly freely in space, dies". The Guardian. December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 378.

- ^ a b Orloff 2000, pp. 270−271.

- ^ NASA (September 2007). "Astronaut Bio: E. Mitchell". Archived from the original on December 22, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 57–59.

- ^ NASA (February 1994). "Astronaut Bio: W. Pogue". Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ "Astronauts Pogue, Carr Retire". The Indiana Gazette. Indiana, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. August 25, 1975. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 59–61.

- ^ NASA (December 1994). "Astronaut Bio: Stuart Allen Roosa". Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 61–62.

- ^ NASA (January 1983). "Astronaut Bio: John L. Swigert". Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ a b NASA (July 1994). "Astronaut Bio: Paul J. Weitz". Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 63–65.

- ^ NASA (December 1993). "Astronaut Bio: Alfred Merrill Worden". Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ "14 New Astronauts Introduced at Press Conference" (PDF). NASA Roundup. Vol. 3, no. 1. NASA. October 30, 1963. pp. 1, 4, 5, 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 17, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ Collins 2001, p. 181.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 119.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 128.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 156.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood & Swenson 1979, p. 261.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood & Swenson 1979, pp. 217–218.

- ^ "Auto Accident Kills MSC Pilot Givens" (PDF). NASA Roundup. Vol. 6, no. 17. June 9, 1967. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ "Florida Aircraft Crash Kills MSC-Bound C.C.Williams" (PDF). NASA Roundup. Vol. 6, no. 26. October 13, 1967. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 174.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 198–201.

- ^ Compton 1989, pp. 219–221.

- ^ a b c d Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 307–310.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 346–348.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 360–361.

References

[edit]- Atkinson, Joseph D.; Shafritz, Jay M. (1985). The Real Stuff: A History of NASA's Astronaut Recruitment Program. Praeger special studies. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-005187-6. OCLC 12052375.

- Brooks, Courtney G.; Grimwood, James M.; Swenson, Loyd S. Jr. (1979). Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. NASA History Series. Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA. ISBN 978-0-486-46756-6. LCCN 79001042. OCLC 4664449. SP-4205. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Burgess, Colin (2013). Moon Bound: Choosing and Preparing NASA's Lunar Astronauts. Springer-Praxis books in space exploration. New York; London: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-3854-0. OCLC 905162781.

- Collins, Michael (2001) [1974]. Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys. New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1028-7. OCLC 45755963.

- Compton, William D. (1989). Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1045558568. SP-4214. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- Homer, Courtney V. K. (2019). Spies in Space: Reflections on National Reconnaissance and the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (PDF). Chantilly, Virginia: Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance. ISBN 978-1-937219-24-6. OCLC 1110619702. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Orloff, Richard W. (2000). Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Series. Washington, DC: NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. ISBN 978-0-16-050631-4. LCCN 00061677. OCLC 829406439. SP-2000-4029. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- Shayler, David J.; Burgess, Colin (2007). NASA's Scientist Astronauts. Chichester: Praxis Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-21897-7. OCLC 1058309996.

- Shayler, David J.; Burgess, Colin (2017). The Last of NASA's Original Pilot Astronauts. Chichester: Springer-Praxis. ISBN 978-3-319-51012-5. OCLC 1023142024.

- Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle. New York: Forge. ISBN 978-0-312-85503-1. OCLC 937566894.

- Swenson, Loyd S. Jr.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1966). This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury (PDF). The NASA History Series. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. OCLC 569889. NASA SP-4201.