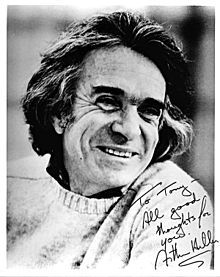

Arthur Hiller

Arthur Hiller | |

|---|---|

Hiller directing Love Story in 1970 | |

| Born | November 22, 1923[1] Edmonton, Alberta, Canada |

| Died | August 17, 2016 (aged 92) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Sinai Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles |

| Occupation | Director |

| Years active | 1955–2006 |

| Spouse |

Gwen Pechet

(m. 1948; died 2016) |

| Children | 2 |

Arthur Hiller, OC (November 22, 1923[a] – August 17, 2016) was a Canadian television and film director with over 33 films to his credit during a 50-year career. He began his career directing television in Canada and later in the U.S. By the late 1950s, he was directing films, most often comedies, but also dramas and romantic subjects, such as in Love Story (1970), which was nominated for seven Oscars.

Hiller collaborated on films with screenwriters Paddy Chayefsky and Neil Simon. Among his other films were The Americanization of Emily (1964), Tobruk (1967), The Hospital (1971), The Out-of-Towners (1970), Plaza Suite (1971), The Man in the Glass Booth (1975), Silver Streak (1976), The In-Laws (1979), Making Love (1982), and Outrageous Fortune (1987).

Hiller served as president of the Directors Guild of America from 1989 to 1993 and president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from 1993 to 1997. He was the recipient of the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 2002. An annual film festival in Hiller's honor was held from 2006 until 2009 at his alma mater, Victoria School of Performing and Visual Arts.

Early life and military service

[edit]Hiller was born in November 1923 in Edmonton, Alberta, the son of Rose (Garfin) and Harry Hiller. His family was Jewish, and had emigrated from Poland in 1912. He had two sisters, one 13 years older and one 11 years older. His father operated a second-hand musical instruments store in Edmonton. Hiller recalled that when he occasionally traveled home while he was in college, the black people he met with "treated me like a king. Why? Because they loved my father. They told me that unlike other shopkeepers, he treated them like normal folks when they went to his store. He didn't look down on them".[7]

Although his parents were not professionals in theater or had much money, notes Hiller, they enjoyed putting on a Jewish play once or twice a year for the Jewish community of 450 people, mainly to keep in touch with their heritage. Hiller recalls they started up the Yiddish theater when he was seven or eight years old; he helped set carpenters build and decorate the sets. When he was eleven, he got a role acting as an old man, wearing a long beard and the payot. He says that "the love of theater and music and literature my parents instilled in me" contributed to his later choosing to direct TV and films.[8]

After he graduated from high school, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1941 during World War II. He served with 427 Lion Squadron as a navigator on four-engine Handley Page Halifax heavy bombers flying from Leeming, Yorkshire on Operations over Nazi-controlled territory in Europe.[9]

After he returned from serving in the military, Hiller enrolled in and later graduated from University College, Toronto with a Bachelor of Arts in 1947. After Israel was declared a state in 1948, he and his wife unsuccessfully tried to join the Israeli army because the country came under attack.[b]

Hiller returned to college and earned a Master of Arts in psychology in 1950. One of his early jobs, after graduating, was with Canadian radio directing various public affairs programs.[11]

Directing career

[edit]Arthur Hiller was calm, quiet and he knew exactly what he wanted. He never told you what to do. He took what you had and very gently focused it. It was such a joy to work with him.

Hiller began his career as a television director with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. NBC, one of the main networks in the United States, seeing his work in Canada, offered him positions directing television dramas. Over the next few years, his work for the small screen included episodes of Thriller, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Rifleman, Gunsmoke, Naked City, Perry Mason, and Playhouse 90.[13]

1950s–1960s

[edit]Hiller directed his first film, The Careless Years (1957), the story of a young couple eloping developed by Bryna Productions. This was followed by This Rugged Land (1962), originally made for television but then released as a film, and then Miracle of the White Stallions (1963), a Walt Disney Productions film. With these first films, Hiller already showed competence in directing unrelated subjects successfully.[13]

He next directed a satirical anti-war comedy by screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky, The Americanization of Emily (1964), starring James Garner and Julie Andrews. It was the first of two film collaborations with Chayefsky. The film, nominated for two Academy Awards, would establish Hiller as a notable Hollywood director and, according to critics, "earned him a reputation for flair with sophisticated comedy."[13] The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote that Hiller's "brisk direction" of Chayefsky's script included some "remarkably good writing with some slashing irreverence."[14]

In 1964 Hiller also directed the first episode of the television series The Addams Family. This was followed by the comedy Promise Her Anything (1965), with Warren Beatty and Leslie Caron and Penelope (1966), starring Natalie Wood. In a move away from comedy, he directed the desert warfare drama, Tobruk (1967), starring Rock Hudson and George Peppard, about a North African Campaign during World War II. The film was nominated for one Academy Award and showed Hiller capable of handling action films as well as comedy.[13] Around the same time, he returned to comedy with The Tiger Makes Out (also 1967), starring Eli Wallach and Anne Jackson, and featured Dustin Hoffman's film debut. Popi (1969), recounts the tale of a Puerto Rican widower, starring Alan Arkin, struggling to raise his two young sons in the New York City neighborhood known as Spanish Harlem. Arkin was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor.[15]

1970s

[edit]All I knew at first was that I liked him and respected him, and then I grew to adore him. Whatever Arthur asked of me, I did to the best of my ability. And I was blessed to be in such safe hands. Every piece of that experience was protected. He wasn't casual about his work in any way—you knew exactly what he wanted you to do. He was meticulous.

Hiller directed Love Story (1970), his best known work and most successful at the box-office.[13] The film stars Ryan O'Neal and Ali MacGraw in a romantic tragedy, and it was nominated for 7 Academy Awards including Best Director. The American Film Institute ranks it No. 9 in their list of the greatest love stories. Critic Roger Ebert disagreed with some critics who felt the story was too contrived:[17] "Why shouldn't we get a little misty during a story about young lovers separated by death? Hiller earns our emotional response because of the way he's directed the movie...The movie is mostly about life, however, not death. And because Hiller makes the lovers into individuals, of course we're moved by the film's conclusion. Why not?"[17]

The following year Hiller again collaborated with screenwriter Paddy Chayevsky in directing The Hospital (1971), a satire starring George C. Scott which has been described as being his best film.[13] It is a black comedy about disillusionment and chaos within a hospital setting.[13] Chayevsky received the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. In directing the film, Hiller tried to create a sense of action and movement by keeping the camera mobile and using handheld cameras as much as possible.[13] His goal was to have the camera reflect the chaos and confusion taking place in the hospital. "I've always liked that sort of realistic feel," he states. "I wanted the feeling that the audience was peeking around the corner."[18]

Hiller directed two comedy films in collaboration with playwright Neil Simon.[19] The first film was The Out-of-Towners (1970), starring Jack Lemmon and Sandy Dennis, who were both nominated for Golden Globe awards for their roles. Their next collaboration was Plaza Suite (1971), starring Walter Matthau, which was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture. Both films were driven by intense comedy dialogue and were considered "crisply directed" by reviewers.[13]

Hiller returned to directing serious drama with The Man in the Glass Booth (1975), starring Maximilian Schell, in a screen adaptation of a stage play written by Robert Shaw. Schell played the role of a man trying to deal with questions of self-identity and guilt as a survivor of the Holocaust during World War II. For his highly emotional role, Schell was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor and the Golden Globe Award.[20]

Returning to comedy, Hiller directed Silver Streak (1976), starring Gene Wilder, Jill Clayburgh and Richard Pryor. The film was well received by critics and is rated No. 95 on the AFI's best comedy films. He directed another comedy, The In-Laws (1979), with Peter Falk and Alan Arkin, which was also a critical and commercial success.[21]

1980s

[edit]He was good director who wanted to know all about the subject. I took Arthur on a tour of the bars one night. Arthur is a real straight Jewish guy, married to the same woman for a hundred years, kids, and everything so far removed from the scene that it was like he was doing a movie about aliens.

Hiller directed the film Making Love, which was released in February 1982, a story of a married man coming to terms with his homosexuality. Author! Author! (also 1982), starred Al Pacino. The following year Hiller directed Romantic Comedy (1983), starring Dudley Moore and Mary Steenburgen. His next comedy, The Lonely Guy (1984), starred Steve Martin as a greeting card writer and was followed by Teachers (1984), a comedy-drama film starring Nick Nolte.[23]

Outrageous Fortune (1987) stars Shelley Long and Bette Midler. The film was successful at the box office, with Midler being nominated or winning various awards. The film was followed by See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989), another comedy again starring Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor. Pryor plays a blind man and Wilder a deaf man who work together to thwart a trio of murderous thieves.[23]

1990s

[edit]The 1990s saw Hiller directing a number of films, most of which received negative or mixed reviews: Taking Care of Business (1990); The Babe (1992), a biographical film about Babe Ruth, portrayed by John Goodman; Married to It (1993) and Carpool (1996). In 1997, Hiller helmed the infamous flop An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn, which mirrored its title when Hiller requested his name be removed from the picture – thus truly making it an Alan Smithee film. Nine years later, when he was in his 80s, Hiller directed National Lampoon's Pucked (2006), his last film, which starred rock star Jon Bon Jovi.[11]

Influences

[edit]In an interview with journalist Robert K. Elder for The Film That Changed My Life,[18] Hiller states that the film Rome, Open City (1945) had had a strong influence on his career because he saw it right after leaving the military where he was a bomber navigator in the Canadian Air Force.[18] The film is set during the Nazi occupation of Italy and shows the priesthood and the Communists teaming up against the enemy forces. Hiller commented, "You just get the strongest emotional feelings about what happened to people in Italy."[18]

Hiller preferred his scripts to contain "good moral values," a preference which he says came from his upbringing.[c] He wanted high quality screenplays whenever possible, which partly explains why he collaborated on multiple films with both Paddy Chayefsky and Neil Simon. Hiller explains his rationale:

Storytelling is innate to the human condition. Its underpinnings are cerebral, emotional, communal, psychological. One of the storyteller's main responsibilities is to resonate in the audience's psyche a certain something at the end of it all, to emotionally move the audience, to compel the audience to "get it" on a visceral level.[25]

Awards and honors

[edit]

Hiller served as president of the Directors Guild of America (DGA) from 1989 to 1993[26] DGA presented Hiller with the Robert B. Aldrich Award in 1999 and the DGA Honorary Life Member Award in 1993. In 1970 he received a DGA Award nomination for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Feature Film for Love Story.[26] He was also a member of the National Film Preservation Board of the Library of Congress from 1989 to 2005[26] and President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from 1993 to 1997.[27] He also served on the board of the National Student Film Institute.[28][29]

He received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the 2002 Academy Awards ceremony in recognition of his humanitarian, charitable and philanthropic efforts.[30] In 2002, he was honoured with a star on Canada's Walk of Fame in Toronto.[31] In 2006, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada.[32] Writer and producer William Froug said that "Hiller is that rare and hugely successful gentleman who has remained humble all his life."[30]

He received an honorary degree of Doctor of Fine Arts from the University of Victoria in June 1995.[33] He received an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D) from the University of Toronto in November 1995.[34]

Personal life and death

[edit]In 1948, he married Gwen Pechet, who was also Jewish; they had two children and two grandchildren.[35][36] His wife died on June 24, 2016.[37] They were married for 68 years.[2] Hiller died almost two months later in Los Angeles on August 17, 2016, at the age of 92 from natural causes.[38][39] Hiller was portrayed by actor Jake Regal in the 2022 miniseries The Offer.

Filmography

[edit]

|

|

Notes

[edit]- ^ The New York Times claims he was born on November 13, 1923,[2] while most other sources list it as the 22nd (Los Angeles Times, Film Reference, The Hollywood Reporter, and Katz's Film Encyclopedia).[3][4][5][6]

- ^ He said that "Israel was immediately attacked by five different Arab armies ... I volunteered, but they turned me down because I was married. I drove down to Seattle to try to volunteer from the United States, but again was turned down because I was married. My wife agreed to volunteer too, but again, 'No.' ... I admire their [Israelis'] determination and dignity of purpose with high ethical standards as they try to make their country safe for democracy, while the countries around them try to make the Arab world safe from democracy.[10]

- ^ "I prefer them [scripts] with good moral values, which comes from my parents and my upbringing ... Even in my smaller, lesser films, at least there's an affirmation of the human spirit."[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Archive of American Television, 2003 interview

- ^ a b "Arthur Hiller, 'Love Story' Director and Box-Office Magnet, Dies at 92", The New York Times, August 17, 2016

- ^ "Arthur Hiller dies at 92; former academy president and director of 'Love Story'", Los Angeles Times, August 17, 2016

- ^ "Arthur Hiller". filmreference.com.

- ^ The Hollywood Reporter, August 17, 2016

- ^ Katz, Ephraim. The Film Encyclopedia, Collins Reference (2012) p. 672

- ^ Grodin, Charles. If I Only Knew Then ... Learning from Our Mistakes, Springboard Press (2007) p. 78

- ^ King, Alan. Matzo Balls for Breakfast: and Other Memories of Growing Up Jewish, Simon & Schuster (2004) p. 215

- ^ Arthur Hillerdominion.ca Archived July 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dershowitz, Alan. What Israel Means to Me: By 80 Prominent Writers, Performers, Scholars, Politicians, and Journalists, John Wiley & Sons (2006) pp. 183–185

- ^ a b "Arthur Hiller, Oscar-nominated 'Love Story' director, dies at 92". The Washington Post. August 17, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Parla, Paul. Screen Sirens Scream! Interviews with 20 Actresses, McFarland (2000) p. 21

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Downs, Jacqueline (2001). Allon, Yoram; Cullen, Del; Patterson, Hannah (eds.). Contemporary North American Film Directorslocation=London. Wallflower Press. pp. 243–44. ISBN 9781903364529.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley. The Americanization of Emily review, The New York Times, 28 October 1966.

- ^ Alan Arkin Golden Globe nominations, Golden Globe Awards

- ^ "Ali MacGraw on the Making of 'Love Story' and Its Beloved Director Arthur Hiller", Town & Country, August 30, 2016

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger. Roger Ebert's Four Star Reviews—1967–2007, Andrews McMeel Publishing (2007) p. 443

- ^ a b c d Hiller, Arthur. Interview with Robert K. Elder. The Film That Changed My Life, Chicago Review Press, 2011. p. 162

- ^ Erskine, Thomas L. Video Versions: Film Adaptations of Plays on Video, Greenwood Press (2000) p. 258

- ^ "Maximilian Schell 1930-2014", CBS News

- ^ "The In-laws", Rottentomatoes, 90% rating

- ^ Marcus, Eric. Making Gay History, HarperCollins (2002) p. 234

- ^ a b Baxter, Brian (August 18, 2016). "Arthur Hiller obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Arthur Hiller, Oscar-nominated 'Love Story' director, dies at 92", The Washington Post, August 17, 2016

- ^ Wright, Kate. Screenwriting Is Storytelling, The Berkeley Publishing Group (2004) foreword

- ^ a b c "In Memoriam: Arthur Hiller 1923–2016", Directors Guild of America, August 17, 2016

- ^ "Statement Regarding the Passing of former Academy President Arthur Hiller", Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, August 17, 2016

- ^ National Student Film Institute/L.A: The Sixteenth Annual Los Angeles Student Film Festival. The Directors Guild Theatre. June 10, 1994. pp. 10–11.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Los Angeles Student Film Institute: 13th Annual Student Film Festival. The Directors Guild Theatre. June 7, 1991. p. 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Froug, William. How I Escaped from Gilligan's Island, Univ. of Wisconsin Press (2005) p. 78

- ^ Canada's Walk of Fame

- ^ Hiller named Officer of the Order of Canada Archived February 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "University of Victoria -Honorary degree recipients - University of Victoria".

- ^ "University of Toronto Honorary Degree Recipients 1850 - 2016" (PDF). University of Toronto. September 14, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2012.

- ^ "Gwen Hiller, Wife of 'Love Story' Director Arthur Hiller, Dies at 92". The Hollywood Reporter. June 26, 2016.

- ^ "Pechet (family)". Society of Alberta Archives. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Gwen Hiller, Wife of 'Love Story' Director Arthur Hiller, Dies at 92", The Hollywood Reporter, 26 June 2016

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (August 17, 2016). "Arthur Hiller Dies: Oscar-Nominated 'Love Story' Director Was 92". Deadline. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Carmel Dagan (June 23, 2014). "Arthur Hiller Dead: 'Love Story' Director Was 92". Variety. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

External links

[edit]- 1923 births

- 2016 deaths

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- American television directors

- Best Director Golden Globe winners

- Burials at Mount Sinai Memorial Park Cemetery

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation people

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- Canadian people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Canadian television directors

- Film directors from Edmonton

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award winners

- NBC

- Officers of the Order of Canada

- Presidents of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- Royal Canadian Air Force personnel of World War II

- University of Toronto alumni

- Victoria School of Performing and Visual Arts alumni

- Jewish film people

- Canadian comedy film directors

- Fantasy film directors