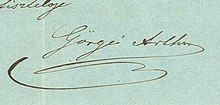

Artúr Görgei

Artúr Görgei de Görgő et Toporc | |

|---|---|

Artúr Görgei, painting by Miklós Barabás | |

| Military Dictator of Hungary Acting civil and military authority | |

| In office 11 August 1849 – 13 August 1849 | |

| Monarchs | Francis Joseph I (unrecognized) |

| Prime Minister | Bertalan Szemere |

| Preceded by | Lajos Kossuth (Governor-President) |

| Succeeded by | Revolution suppressed |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 7 May 1849 – 7 July 1849 | |

| Prime Minister | Bertalan Szemere |

| Preceded by | Lázár Mészáros |

| Succeeded by | Lajos Aulich |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Arthur Görgey 30 January 1818 Toporc, Szepes County, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire (today Toporec, Slovakia) |

| Died | 21 May 1916 (aged 98) Budapest, Austria-Hungary |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Spouse | Adéle Aubouin |

| Children | Berta Kornél |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Army |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Croatian Surrender at Ozora Battle of Bruck Battle of Schwechat Battle of Moson Battle of Tétény Battle of Szélakna Battle of Isaszeg First Komárom Siege of Buda Battle of Pered Battle of Győr Second Komárom Second Vác |

Artúr Görgei de Görgő et Toporc (born Arthur Görgey; Hungarian: görgői és toporci Görgei Artúr, German: Arthur Görgey von Görgő und Toporc; 30 January 1818 – 21 May 1916) was a Hungarian military leader renowned for being one of the greatest generals of the Hungarian Revolutionary Army.

In his youth, Görgei was a talented chemist, with his work in the field of chemistry being recognized by many renowned Hungarian and European chemists. However, now he is more widely known for his role in the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849. As the most successful general and greatest military genius of the Hungarian Revolutionary Army, he was the leader of the victorious Spring Campaign and liberated almost all of Western Hungary from Austrian occupation. In recognition of his military successes, he was awarded by the Hungarian Government and was appointed Minister of War. In the last days of the revolution, he was appointed the "dictator" of Hungary. On 13 August 1849, when he realised that he would not be able to fight newly arrived and superior Austrian and Russian armies, he surrendered his troops to the Russians at Világos, thus ending the revolution.

Görgei's difficult relationship with Lajos Kossuth, the foremost politician and president-governor of revolutionary Hungary, impacted the course of the war of independence, Görgei's military career, and his post-revolutionary life until his death. During his campaigns in the winter and summer of 1848–1849. Görgei clashed with Kossuth over their differing opinions on military operations and because Görgei disapproved of the Declaration of the Hungarian Independence, whose chief proponent was Kossuth. The latter refrained from naming Görgei as commander-in-chief of the Hungarian army, naming weak commanders, such as Henryk Dembiński or Lázár Mészáros, instead, thus weakening the army.

After his surrender to the Russian army, he was not executed, like many of his generals, due to Russian intercession, but was taken by the Austrians to Klagenfurt, in Carinthia, and was kept under surveillance until 1867, when amnesty issued as a result of the Hungarian-Austrian Compromise and the founding of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. He then was able to return to Hungary. Over several years of hardships in different parts of Hungary, Görgei unsuccessfully tried to find a suitable job; and his brother, István Görgey, provided him with a place to live in Visegrád, where Görgei lived the last decades of his life.

After Görgei's return and for the rest of his life, Hungarian public opinion was hostile, because of some false accusations. Kossuth's Letter from Vidin, written in the aftermath of Görgei's surrender, instilled a long-lasting hatred of Görgei amongst the Hungarians, many of whom came to believe that he was a traitor. In the 20th century, this characterization was challenged by modern research. As a result, Görgei is less often considered treasonous, and his reputation as one of the most talented and successful Hungarian generals of the 19th century has been restored, being now regarded as one of Hungary's greatest historical heroes.

Görgey or Görgei?

[edit]The earlier books and articles about Artúr Görgei usually gave his surname as Görgey, which is how it had been given at his birth. For example, Sándor Pethő's bibliographical book Görgey Artúr (Budapest, 1930), or Artúr's younger brother István Görgey's Görgey Arthur ifjusága és fejlődése a forradalomig [The youth of Artúr Görgey, and his development until the revolution] (Budapest, 1916) and Görgey Arthur a száműzetésben 1849–1867 [Artúr Görgey in exile, 1849–1867] (Budapest, 1918). But, recent historiography spells it Görgei (Róbert Hermann's and Tamás Csikány's works, for example).

In Hungarian surnames, the "y" instead of an "i" (used today), usually appears as the last letter of the names of nobles (as a locative adverb suffix: for example, 'Debreceni', meaning "from Debrecen"), because their names appeared in writing earlier than the names of people of common origin, so the nobiliary surnames retained the archaic spelling of the period when they were first written down. The surnames of the common people, which appeared later, after Hungarian spelling changed, had an "i" as the last letter.

Being of noble birth, initially, Görgei had a "y" at the end of his surname; but during the 1848–49 revolution, a period of an anti-nobiliary reaction, many Hungarians from noble families changed the last letter of their surnames from "y" to "i". For example, the renowned novelist Mór Jókay became Mór Jókai. Görgei similarly changed his name, because of his progressive liberal views. Even after the revolution was suppressed, he kept using Görgei instead of Görgey; and although in some works which appeared after his death, and translations to Hungarian of his works—such as Mein Leben und Wirken in Ungarn in den Jahren 1848 und 1849 [My life and work in Hungary in 1848 and 1849], translated by his younger brother István Görgey in 1911, when the Görgey form is used—Görgei was the preferred form until his death,[1] which is why this article also uses this form.

Early life

[edit]Görgei was born as Johannes Arthur Woldemár Görgey at Toporc in Upper Hungary (today Toporec, Slovakia) on 30 January 1818 to an impoverished Hungarian noble family of Zipser German descent who immigrated to the Szepes (today Spiš) region during the reign of King Géza II of Hungary (1141–1162). During the Reformation, they converted to Protestantism. The family name refers to their origin from Görgő village (Hungarian: görgői, lit. "of Görgő"), today Spišský Hrhov in Slovakia.

In 1832, Görgei enrolled in the sapper school at Tulln, profiting from a tuition-free place offered by a foundation. Because his family was poor, this was a great opportunity for him; but initially, he did not want to be a soldier. During this period, he wrote to his father that he would rather be a philosopher or scientist than a soldier.[2] He spent almost thirteen years in this school, receiving a military education. He decided not to accept money from his family, and ate very little, and wore poor clothes in an effort to train himself for a hard life.[1] Records from the school show that his conduct was very good, he had no errors, his natural talents were exceptional, and his fervency and diligence were constant, being very severe with himself but also with the others.[3]

Despite this, in his letters he wrote that he despised the life of a soldier because he had to obey officers whom he did not respect and that he dreamed about a free and active life that he could not find in the army.[4] Following graduation, he served in the Nádor Hussar regiment, undertaking the role of adjutant. By 1837, he had reached the rank of lieutenant and entered the Hungarian Noble Guard at Vienna, where he combined military service with a course of study at the university.[1]

Start of a promising career in chemistry

[edit]In 1845, on his father's death, Görgei happily left the army, feeling that the military life did not suit him, to be a student of chemistry at the University of Prague.[2] He loved chemistry, writing this to his friend, Gusztáv Röszler, who had recommended him to professor Josef Redtenbacher, a great chemist at that time:

[Y]our recommendation to Redtenbacher made me very happy. I am gaining life as never before. The science of chemistry itself, but also the leading of it by such a great professor as Redtenbacher, totally conquered me.[5]

Görgei's work in chemistry from this period are worthy of note: he conducted research into coconut oil, discovering the presence in it of decanoic acid and lauric acid. He started his research in the spring of 1847 in Prague but finished the experiments at home in Toporc, sending the results to the Imperial and Royal Academy of Vienna on 21 May 1848.[2] His method for the separation of the fatty acids homologs was not the traditional way of using fractional distillation, but instead using the solubility of barium salts. His research can be summarized as follows:

- He detected the presence of lauric acid (C12) and decanoic acid (C10) in coconut oil.

- He produced lauric ethyl ether.

- He determined some physical properties of the distillation of lauric acidic barium.

- He discovered that, in coconut oil, the undecylic acid (C11) was a mixture of lauric and decanoic acids.[6]

Just before Görgei started his study, a French chemist named Saint-Évre wrote an article in which he announced the discovery of the undecylic acid. At first, Görgei was disappointed that with this announcement his work would be pointless, but then he noticed that the French chemist was wrong in thinking that the undecylic acid was an original, undiscovered acid rather than a mixture of lauric and decanoic acids, which he demonstrated in his study.[6]

Görgei's results were published by Redtenbacher under the title: Über die festen, flüchtigen, fetten Säuren des Cocusnussöles [About the solid, volatile, fatty acids of coconut oil] (Sitzungsberichte der mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der k. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien [Meeting reports of the mathematical and scientific department of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna]. 1848. 3.H. p. 208–227); by Justus von Liebig in Heidelberg (Annalen der Chemie und Pharmazie. 1848. 66. Bd. 3.H. p. 290–314); and again, more than 50 years later, by Lajos Ilosvay in 1907 in the Magyar Kémiai Folyóirat [Hungarian Chemistry Magazine]. Görgei's skills and achievements in chemistry were praised by Vojtěch Šafařík and Károly Than.[7]

Redtenbacher wanted to hire Görgei as a chemist at the university of Lemberg, but in the end Görgei retreated to the family domains at Toporc, because his uncle Ferenc had died and his widow had asked him to come home and help the family.[7] After the defeat of the revolution, in 1851, Görgei received an award and 40 Hungarian pengős, as an honorarium, from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences for his achievements in chemistry during the two and a half years he worked in this field.[2]

Military career

[edit]Becoming a general

[edit]In March 1848, during the early days of the Hungarian revolution, Görgei was in Vienna and Prague, preparing to marry Adéle Aubouin, a French-Huguenot girl, who was the lady companion of a maiden relative of Redtenbacher. Görgei married her in the Lutheran church in Prague.[1] After he finished his research in chemistry at his home at Toporc, he went to Pest, hearing about the 17 May 1848 call of the Hungarian government for decommissioned officers to join the newly established Hungarian army. He was conscripted into the revolutionary honvéd (army) at the rank of captain, with the 5th Hungarian battalion, from Győr, to train newly enlisted men. Shortly after that, a former companion-in-arms, Lieutenant Imre Ivánka, Prime Minister Lajos Batthyány's secretary, recommended him to Batthyány to work in the ministry. Görgei worked with Ivánka on a plan to organize the voluntary mobile national guards into four camps and was named captain of the national guard camp at Szolnok.[1] Görgei was later assigned to go to Istanbul and Smyrna (today İzmir) to buy weapons for the newly conscripted Hungarian troops; but soon it became clear that their merchants were not trustworthy. Instead, Görgei was sent to the state factory at Wiener Neustadt to buy percussion caps and to Prague to buy primers from the Sellier & Bellot factory; he accomplished this mission successfully.[1] The egalitarian ideals of the revolution made him change his noble surname from Görgey to Görgei. He first met Kossuth on 30 August 1848, when he proposed building a factory to produce percussion caps and primers, for which the politician promised to obtain funds.[8]

In August 1848, the danger of an imperial attack against Hungary grew day by day. Finally, at the beginning of September, King Ferdinand V of Hungary, the Habsburg emperor under the name Ferdinand I of Austria, dismissed the Batthyány Government and authorized the Ban of Croatia, Josip Jelačić. On 11 September 1848, when the troops of Jelačić crossed the Dráva river to enter Hungary, Görgei's national guards were ordered to come from Szolnok to Csepel Island to keep an eye on the movements of Croatian supplies. Here, Görgei organized the villagers from the region to observe and capture the envoys and supply carriages sent from Croatia to Jelačić and back. On 29 September, the Croatian ban sent the wealthy pro-Habsburg Hungarian noble, Count Ödön Zichy, to inform the commanders of the Croatian reserve troops, led by Major General Karl Roth and Major General Nicolaus Philippovich von Philippsberg, about his decision to attack the Hungarian capitals of Buda and Pest. Görgei's troops captured Zichy, who was charged with treason for his pro-Austrian activities, court-martialed, and hanged.[1] This bold act of Görgei impressed Kossuth, who saw in him a great future leader of the Hungarian armed forces, promoting the 30-year-old major to the rank of general. Later, when a conflict between the two arose, Kossuth tried to prevent Görgei from becoming the leader of the main Hungarian forces because he saw him as his greatest opponent; this conflict caused difficulties in the Hungarian struggle for independence.[1]

Autumn and winter campaigns, 1848–49

[edit]After the Battle of Pákozd of 29 September 1848—in which the Hungarian troops, led by János Móga, defeated the troops of Jelačić, saving the Hungarian capitals—Görgei's 2,500 troops, reinforced by 16,500 peasant militia from Tolna county, observed the movements of the Croatian reinforcements, led by Roth and Philipovich, blocked their retreat, and eventually forced them to surrender. Görgei's superior was General Mór Perczel, a nobleman with almost no military experience, who lacked Görgei's knowledge of the theory and practice of warfare. Seeing that some of Perczel's orders were wrong and could allow for the escape of the enemy, Görgei gave contradictory orders to his troops. Perczel became angry and wanted to put Görgei in front of a firing squad; but when the latter explained to the officers' council the reasons for his actions, Perczel accepted his plans and ostensibly pardoned, but continued to resent, him. On 7 October 1848, thanks to Görgei's plans, Roth's and Philipovich's Croatian troops were forced to surrender at Ozora, the Hungarians taking almost 9,000 prisoners, together with their weapons and ammunition, including 12 guns; this being the most successful pincer maneuver of the Hungarian freedom war.[9][10]

– Red: Croatian troops,

– Black: Hungarian troops

On 6 October, after the defeat of Jelačić's army, the people of Vienna revolted, forcing the emperor to flee to Olmütz. The Hungarian troops led by János Móga, who had defeated Jelačić at Pákozd, advanced to the Hungarian–Austrian border; and many people thought that it should come to the aid of the revolutionaries in the imperial capital, which was at that time defended only by the troops of Jelačić. The Hungarian officers, many of whom were foreign and unsure of what to do, said that they would agree to this only if the people of Vienna asked them to do it; but the Viennese revolutionaries were reluctant to officially ask for Hungarian aid. In the meantime, the Austrian commander Windisch-Grätz, having crushed the revolution in Prague, came with his army to Vienna to crush the revolution there, with an overwhelming numerical superiority (80,000 Austrian soldiers against 27,000 Hungarians).

Kossuth, waiting in vain for the Hungarian troops to cross the Austrian border, decided to personally encourage the Hungarian army. In a war council, the old commanders, led by Móga, declared that an assault on the Austrian border would bring with it a Hungarian defeat, pointing at the numerical superiority of the enemy. Kossuth argued, "Our cause is linked with Vienna – separated from it, nobody will give us any importance." He warned that the enlistment period of the Hungarian national guards would expire soon; and if they did not engage the Austrians, they would go home without any fighting. He also said that if only one of the Hungarian commanders would say that he would attack, showing a plan by which success could be achieved, he would make that person the commander. At that moment Görgei stood up and said, "We have no other choice than to advance because if we do not advance, we will lose more than losing three battles." Hearing that, Kossuth wanted to give him the command; Görgei refused.

In the end, Móga remained the commander during the Battle of Schwechat, where the Austrian troops of Windisch-Grätz and Jelačić routed the Hungarian army, which was composed mainly of inexperienced national guards and peasants. Görgei led the advance guard and achieved some success, but the lack of experience of the soldiers and the commanders made all his actions useless, and the panic of the volunteers, who started to flee, decided the battle's outcome.[11] Görgei successfully protected the retreating Hungarians, preventing a complete rout.[12]

On 9 October, after the battle of Schwechat, Görgei was named colonel. On 1 November, Görgei, only 32, was named general and appointed commander of the army of the Upper Danube, being charged with protecting Hungary's western frontier against the imperial army's imminent attack.[13] While he waited for the attack, which ultimately came on 14 December 1848, Görgei reorganized his army, sending home the national guards and the peasant militias—who had been the first to flee from the Schwechat battlefield and were deemed ineffective in fighting against the well trained, professional imperial army—and increased the number of the battalions of the Hungarian Honvéd army, training them for future battles. He debated with Kossuth about how to organize an effective defense of the border, and was forced to accept Kossuth's idea of aligning his units along the border, although he thought that grouping them further back would be a better choice.[1] When, in the middle of December, the Austrian troops under Windisch-Grätz advanced across the Lajta river (the border between Austria and Hungary), Görgei slowly retreated,[14] thus angering Kossuth, who thought that he should fight for every inch of Hungarian territory.[1] Görgei understood that if he would have followed Kossuth's wishes, he would certainly have been crushed by the much superior imperial army (he had 28,000 inexperienced soldiers against Windisch-Grätz's 55,000 imperial troops).[15] On 30 December 1848, at Kossuth's urging and before Görgei arrived, Mór Perczel engaged and was heavily defeated by imperial troops led by Josip Jelačić in the Battle of Mór, thus leaving Görgei alone in a hopeless struggle against a vastly superior Austrian army.[16]

Görgei's retreat from the Hungarian border to Pest, can be seen as only partly successful; but this campaign was his first as commander of such a large, the main army of Hungary, being responsible for retreating before the numerically and technologically superior enemy forces without suffering a decisive defeat, having subordinates and the majority of his soldiers who were equally inexperienced. Although, strategically his decisions were not faultless, tactically he was mostly successful. The maximal goal of defending the border and repulsing the enemy was impossible to achieve, even if Perczel's troops would have joined him at Győr. He managed to accomplish the minimal goal, that of saving his troops from destruction at the hands of the superior forces of Windisch-Grätz. He suffered only two defeats that can be deemed important—at Nagyszombat on 16 December, and at Bábolna on the 28th—but these were mostly due to the inattention of his brigade commanders.[17]

– Red: Austrian troops, red ⚔: Austrian victory,

– Black: Hungarian troops, black ⚔: Hungarian victory

Görgei understood that with his inferior troops he could not stop the main Austrian army; and if he risked battle, he would have suffered a decisive defeat, which would have ended Hungary's bid for independence. In the war council held on 2 January 1849, Görgei convinced the other commanders that there was no other choice than to retreat from the Hungarian capitals.[18] In spite of remonstrations from Kossuth, who wanted him to accept a decisive battle before the Hungarian capitals, Görgei maintained his resolve and retreated to Vác, letting Buda and Pest fall into the hands of the enemy, who entered the cities on 5 January 1849. The Hungarian Committee of National Defense, which temporarily functioned as the executive power in Hungary after the resignation of the Batthyány government on 2 October 1848, retreated to Debrecen.

This retreat had a negative effect on the officers of foreign origin in the Hungarian army, who left in great numbers, which threatened to cause the army's total dissolution. On 5 January 1849, in Vác, irritated by these events and blaming his defeats on the government's interference, Görgei issued the Proclamation of Vác, which blamed the government for the recent defeats and the evacuation of the capitals, but also declared that he, along with his army, would not put down their weapons and that he would fight with all his energy and power against the imperials to defend the Hungarian revolution and the April laws. This proclamation was seen at once by Kossuth as a revolt against his authority, but it convinced the majority of the foreign or wavering officers and soldiers to remain with the army, halting its dissolution, and to defend Hungary with all determination.[19][20]

After the proclamation, Görgei chose to retreat eastward, through the northern Gömör-Szepes Ore and Tátra mountain ranges, and to conduct operations on his own initiative, forcing the Austrian commander Windisch-Grätz to send troops in pursuit as well as keep the bulk of his army around Buda and Pest, to prevent Görgei turning to the west and attacking Vienna,[21] thus preventing the Austrians from attacking the provisional capital of Debrecen, and providing time for the Hungarian troops east of Tisza to reorganize. He also sent needed money and ore supplies from mining towns such as Körmöcbánya, Selmecbánya, and Besztercebánya to Debrecen.[1]

Another of Görgei's goals was to relieve the border fortress of Lipótvár from an enemy siege and to take the defenders and the provisions from this fort to Debrecen; but he saw that this would be too risky, due to the danger of encirclement by the enemy. So, he renounced this plan, and Lipótvár was forced to surrender to the Austrians on 2 February 1849.[21] Despite this, he succeeded in accomplishing other goals mentioned earlier. In the harsh winter, marching in the mountains, several times Görgei and his troops escaped encirclement by the Austrian troops (at one point escaping by opening a formerly closed mine tunnel and passing through it to the other side of a mountain).[22] Then, on 5 February 1849, they broke through the mountain pass of Branyiszkó, defeated General Deym in the Battle of Branyiszkó, and united with the Hungarian troops led by György Klapka on the Hungarian plains.[23]

According to the military historian Róbert Hermann, the one-and-a-half months of Görgei's campaign to the east through northern Hungary was a strategic success, because Görgei prevented Windisch-Grätz from attacking with all his forces towards Debrecen, where the Hungarian government had taken refuge, thus putting an end to the Hungarian revolution, and because he provided enough time for the concentration of the Hungarian forces behind the Tisza river, clearing the Szepes region of enemy troops, and thus securing with this the whole territory between Szeged and the Galician border as a Hungarian hinterland from which a future counterattack could be launched. During his retreat, he fought five notable battles, of which he lost two (Szélakna on 21 January 1849, and Hodrusbánya on the 22nd), scored a draw (at Turcsek 17 January 1849), and won two (Igló on 2 February 1849, and Branyiszkó on the 5th).[24]

Kossuth, who did not want to give the supreme command to Görgei, conferred it on the Polish general Henryk Dembiński. Many officers from Görgei's Army of the Upper Danube (György Kmety, Lajos Aulich) were astonished at Kossuth's decision and sought to protest, but Görgei ordered them to accept it.[25] One of the first decisions of the new commander was to order many of the Hungarian units, under the lead of Görgei and Klapka, to retreat, enabling the Austrian troops of General Franz Schlik to escape from their encirclement.[21] On 25–27 February 1849, Dembiński, after making mistake after mistake, lost the Battle of Kápolna (in which Görgei's VII corps could not participate; because of Dembiński's poor deployment, the VII corps arriving at the battlefield only after the battle ended).[26] The Hungarian officers revolted against the Polish commander and demanded his dismissal and that a Hungarian general be put in his place.[27]

Among the generals whom the Hungarian officers would accept as the supreme commander, Görgei was the most popular; and in an officers meeting held in Tiszafüred, in the presence of the government's chief commissary Bertalan Szemere, they elected Görgei as the commander-in-chief, with their decision ratified by Szemere. When Kossuth heard about this, he was angered and rushed to the military camp, thinking that Görgei was its organizer and declaring that he would order Görgei executed for this revolt. But when he arrived at Tiszafüred and saw that the majority of the officers supported Görgei, Kossuth was forced to accept the situation. However, he declared that the final decision about who would be the commander would be announced after he presented the facts to the Parliament.[28] In Debrecen, Kossuth and his political supporters ignored the wishes of the Hungarian generals to name Görgei and designated Antal Vetter as commander-in-chief.[29] On 8 March, by way of consolation, Görgei was decorated with the Second Class Military Order of Merit.[30]

Spring campaign and Minister of War

[edit]In the middle of March, Vetter planned a Hungarian campaign to chase Windisch-Grätz and his troops out of Hungary. On 16–17 March, the Hungarian troops crossed the Tisza river; but, due to some unfounded rumors, Vetter decided to retreat to the starting position. During these events, Görgei was the only military commander who achieved notable success, by advancing from the north through Tokaj, Gyöngyös, Miskolc, and Mezőkövesd, by which he succeeded in diverting Windisch-Grätz's attention from the crossing of the main Hungarian forces at Cibakháza, forcing the Austrian commander to take a defensive position, and thus ceding the initiative to the Hungarians before the start of their Spring Campaign.[31]

At the end of March 1849, Görgei was named as acting commander by Kossuth because Vetter had fallen ill. Before this, Kossuth again hesitated, trying to find somebody else, even thinking of taking command of the army himself; but when the corps commanders—György Klapka, Lajos Aulich, János Damjanich—declared that Görgei was the ablest commander for that job, he had to accept it. Thus, Görgei became acting head only a few days before the start of the spring campaign.[32]

– Red: Austrian army,

– Black: Hungarian army, black ⚔: Hungarian victory

The plan of the spring campaign had to take into account the fact that the enemy troops were numerically superior to the Hungarians. So, it was decided to defeat them in detail.[31] The plan was that the VIIth Hungarian Corps would feint to divert the attention of the Austrian commanders, while the other three Hungarian army corps (the Ist, the IInd, and the IIIrd) would advance from the south, getting around the enemy, and fall on their rear, forcing them to retreat over the Danube, leaving the Hungarian capitals (Pest and Buda) in the hands of the Hungarian army. The minimal objective of the Hungarians was to force the Austrians to retreat from the Danube–Tisza Interfluve. During these operations, due to the faults of some of Görgei's corps commanders (György Klapka and András Gáspár), as well to Windisch-Grätz cautiousness, the latter managed to escape the trap of being surrounded; but nevertheless, because of his defeats at Hatvan (2 April), Tápióbicske (4 April), and Isaszeg (6 April), Windisch-Grätz was forced to retreat from the interfluve, taking refuge in the Hungarian capitals.[33] In two of these battles (Tápióbicske and Isaszeg), the intervention of Görgei on the battlefield, who spoke personally to the hesitant Klapka, ordering him to hold his position and to counterattack, decided the battle for the Hungarians.[34]

The second part of the spring campaign resulted in three important successes for the Hungarian armies: Vác (10 April), Nagysalló (19 April), and Komárom (26 April). The plan was similar to the first part: this time the IInd corps led by General Lajos Aulich, and two brigades led by colonels György Kmety and Lajos Asbóth demonstrated, diverting the attention of Windisch-Grätz from the Ist, IIId, and VIIth corps' pincer maneuver from the northwest, in order to relieve the besieged fortress of Komárom, force the Austrians to retreat from the capitals, and eventually to encircle them. This maneuver resulted in success, except for the encirclement of the enemy troops, which escaped, retreating from all Hungary, except for a strip of land near the Austrian border.[34] These Hungarian successes were achieved despite the changing of the Austrian high command (Alfred Zu Windisch-Grätz, Josip Jelačić, and Ludwig von Welden) and the sending of reinforcement troops under Ludwig von Wohlgemuth from the Austrian hereditary provinces to Hungary.[35]

The spring campaign led by Artúr Görgei, combined with the successes of the Hungarian armies in the other fronts, forced the armies of the Austrian Empire and its allies, which at the beginning of March had controlled three-quarters of Hungary, to evacuate almost all of Hungary, except for a narrow strip of land in the west, Croatia, and a few land pockets and forts. In the battle of Isaszeg, Görgei had been close to encircling and completely destroying Windisch-Grätz's main Austrian army, which could have brought about a decisive end to the war; but the refusal of one of his army corps commanders, András Gáspár, to attack from the north, made possible the enemy escape. Görgei shared some responsibility for the failure to make the best of this opportunity because, wrongly thinking that Gáspár had already begun to attack, he did not urge his general on.[36] Also playing an important role in the liberation of the country were the troops of Józef Bem, who liberated Transylvania,[37] and Mór Perczel, who liberated much of southern Hungary, except for Croatia.[38] However, Görgei was the commander who achieved the greatest success by defeating the main Austrian army—which constituted the most experienced, and best-equipped forces of the Austrian Empire, and had Austria's best as its commanders—forcing them to retreat from the most developed central and western parts of the country, including the capitals.[citation needed]

Görgei achieved his successes with a numerically and technologically inferior army (47,500 Hungarian soldiers, having 198 cannons, vs 55,000 Austrian soldiers with 214 cannons and rockets),[39] which lacked heavy cavalry (relying almost completely on the light Hussar cavalry), and having relatively very few soldiers fighting in the other types of units common in the armies of that period (chasseurs, grenadiers, lancer cavalry, dragoons, cuirassiers),[40] and with constant shortages of weapons and ammunition.[41] Several times these shortages caused the Hungarian infantry to not engage in long shooting duels with the Austrians, but to employ bayonet charges, which were repeated if the initial attempt to break through was unsuccessful, causing the Hungarian infantry heavy casualties.[42]

During the spring campaign, Görgei's tactical outlook changed drastically, from being an extremely cautious commander who planned for slow, calculated movements, to a general full of energy, quick in action and ready to take risks if necessary to achieve his goals. Görgei understood that the main cause of Dembiński's failure was the latter's extreme cautiousness, which prevented him from concentrating his troops before the Battle of Kápolna. Fearful of being encircled, Dembiński had deployed his units so far from each other that they could not support each other when attacked.[31] Görgei started the spring campaign as a mature commander, who let his corps commanders (János Damjanich, Lajos Aulich, György Klapka, András Gáspár) make independent decisions while following a general battle plan, intervening only when needed, as he did at Tápióbicske and Isaszeg, where he turned, by his presence and decisiveness, the tide of battle in his favor.[34] He took great risks at the start of both phases of his spring campaign because he left only a few troops in front of the enemy, while sending the bulk of his army to make encircling maneuvers, which, if discovered, could have led to a frontal attack of the enemy, the breaking of the weak Hungarian front line, cutting of his supply lines, and the occupation of Debrecen, the temporary Hungarian capital.[43] Görgei later wrote in his memoirs that he knew that he could take these risks against such a weak commander as Windisch-Grätz.[34]

According to József Bánlaky and Tamás Csikány, Görgei failed to follow up his successes by taking the offensive against the Austrian frontier,[44] contenting himself with besieging Buda, the Hungarian capital, taking the castle of Buda on 21 May 1849 instead of attacking Vienna and using that strategic opportunity, which the Hungarian victories from the spring campaign created, to win the war.[45][46]

Some of the representatives of the new generation of Hungarian historians, such as Róbert Hermann, believe that the siege of Buda was not a mistake by Görgei because at that point he had not enough troops to attack towards Vienna because the Austrians had concentrated around Pozsony a fresh army that was two times the size of Görgei's, and also far better equipped. To achieve a victory with his tired troops, who had almost completely run out of ammunition, would have been virtually impossible.[47] Görgei hoped that, while he was conducting the siege of Buda, new Hungarian troops would be conscripted, the Hungarian generals who were operating in southern Hungary would send him reinforcements, the issue of lack of ammunition would be resolved; and that then he would have a chance to defeat the Austrian troops. He also knew that the castle of Buda had a 5,000-strong Austrian garrison that controlled the only stone bridge across the Danube, the Chain Bridge, which disrupted the Hungarian supply lines[48] and threatened the Hungarian troops and supply carriages, causing the Hungarians to make a long detour, which caused weeks of delay, and prevented their use of the Danube as a transport route. Besides that, he had to deploy a considerable portion of his force in order to monitor the Austrian troops in Buda, thus weakening any attack westward. Also, the presence in southern Hungary of the 15,000-strong Austrian troops led by Josip Jelačić, which might come north by surprise to help the garrison of Buda, threatened to cut Hungary in two; and only the liberation of Buda could diminish this danger. Kossuth also urged Görgei to take the capital; he hoped that such a success would convince the European powers to recognize Hungary's independence, and prevent a Russian invasion.[49]

All the military and political advice seemed in favor of taking Buda first, rather than moving towards Vienna. According to Hungarian Historian Róbert Hermann, the capture of Buda after three weeks of siege (the only siege of the Hungarian Freedom War that ended in the taking of a fortress by assault; the remaining fortresses and castles were taken, by one or the other side, only after negotiations and then surrender) was one of the greatest Hungarian military successes of the war.[50]

Görgei was not in sympathy with the new regime, and he had refused the First Class Military Order of Merit for the taking of Buda, and also Kossuth's offer of a field-marshal's baton,[51] saying that he did not deserve these and did not approve of the greed of many soldiers and officers for rank and decorations, wanting to set an example for his subordinates. However, he accepted the portfolio of minister of war, while retaining the command of the troops in the field.[52]

Meanwhile, at the parliament in Debrecen, Kossuth formally proposed the dethronement of the Habsburg dynasty,[44] which the parliament accepted, declaring the total independence of Hungary on 14 April 1849.[53] Although he did not oppose it when Kossuth divulged his plan at Gödöllő after the battle of Isaszeg, Görgei was against dethronement because he thought that this would provoke the Austrians into asking for Russian intervention. He thought that declining to demand dethronement and using the significant military successes he had achieved as arguments in an eventual negotiation with the Austrians might convince them to recognize Hungary's autonomy under the rule of the House of Habsburg, and the April Laws of 1848. He believed that this was the only choice to convince the Habsburgs not to ask Russia's help against Hungary, which he thought would cause destruction and national tragedy.

Preventing Russian intervention is why Görgei attempted to initiate secret talks with the Hungarian Peace Party (who were in favor of a compromise with the Austrians), to help him stage a coup d'état to overthrow Kossuth and the Hungarian government led by Szemere, to achieve the position of leadership necessary to start talks with the Habsburgs; but the Peace Party refused to help him, fearing a military dictatorship. So, he abandoned this plan.[54][55] However, Görgei was wrong when he thought that the Hungarian Declaration of Independence had caused the Russian intervention when it came, because the Austrians had asked for, and the Czar agreed to, Russia's sending troops to Hungary before learning of the 14 April declaration.[8]

Supreme commander and dictator of Hungary

[edit]The Russians intervened in the struggle and made common cause with the Austrians, in mid-June 1849 the allies advanced into Hungary from all sides.[44] Görgei found himself before a greatly superior enemy. The reinforcements that Kossuth had promised did not came, because on 7 June General Perczel, the commander of the southern Hungarian army, had suffered a heavy defeat in the Battle of Káty, from an Austro-Croatian army, reinforced with Serbian rebels, led by Josip Jelačić.[56] Perczel could not send the reinforcements because he needed them there.[57] A second problem was that many of his experienced generals, who had proved their talent in the spring campaign, were no longer available: (János Damjanich had broken his leg, Lajos Aulich was ill,[58] and András Gáspár had resigned from the Hungarian army for political reasons.[59]) Görgei was forced to put in their place other officers, who were capable soldiers, but were not experienced as army corps leaders, many of them lacking the capacity to act independently when needed.[52] A third problem was that he could not adequately fulfill the duties of being both supreme commander and head of the war ministry at the same time, being forced to move frequently between Pest and his general staff office near Tata.[60]

Nevertheless, Görgei decided to attack Haynau's forces, hoping to break them and advance towards Vienna before the main Russian troops led by Paskevich arrived from the north. Despite an initial victory in the Battle of Csorna on 13 June,[61] his troops were not so successful afterwards. In the next battle, fought at Zsigárd on 16 June 1849, while he was in the capital to participate in the meeting of the ministry council, his troops were defeated; his presence on the battlefield could have brought a better result.[60] In the next battle, at Pered, fought at 20–21 June, he was present; but, despite all his efforts, the intervention on Haynau's behalf of a Russian division of more than 12,000 soldiers led by Lieutenant General Fyodor Sergeyevich Panyutyin decided the fate of this engagement.[62]

– Red: Austrians, red ⚔: Austrian victory

– Broken red: Russians.

– Black: Hungarians, black ⚔: Hungarian victory

On 26 June Görgei was again in the capital at a ministry council, and tried to convince Kossuth to concentrate all the Hungarian troops, except those from Transylvania and southern Hungary, around Komárom, to decisively strike against Haynau's troops, before the main Russian forces arrived. This plan was maybe the only rational way to end—if not with full success, but with at least a compromise—this war against overwhelmingly superior enemy forces. The place for the Hungarian concentration, the fortress of Komárom (one of the strongest fortresses of the empire), was the best choice, if they wanted to have a chance of success, and avoid having to retreat to the Ottoman Empire.[60] The ministry council accepted Görgei's plan, but unfortunately because of his required presence at the council, Görgei was unable to concentrate his troops against Haynau's army, freshly deployed from the northern to the southern banks of the Danube, when they attacked Győr on 28 June. Görgei arrived only at the end of the battle, when it was too late to rescue the situation for the overwhelmed Hungarian forces (17,000 Hungarians against 70,000 Austro-Russian soldiers); but he managed nevertheless to successfully cover their retreat towards Komárom, by personally leading hussar charges against the advancing enemy forces.[63]

After learning about the defeat at Győr, and the advance of the main Russian forces led by Field Marshal Ivan Paskevich from the north, the Hungarian government—following Kossuth's lead in another ministry council, held this time without Görgei—abandoned Görgei's plan of concentration and ordered him to abandon the fortress and move with the bulk of his troops to southern Hungary, to the confluence of the rivers Maros and Tisza. Görgei thought this new plan completely wrong: that the region which they wanted to concentrate the troops was completely racked by the war, that the most important fortress of the region, Temesvár was in the hands of the enemy, and that this retreat would provide enough time for Haynau and Paskevich to unite their forces against the Hungarians, creating an even greater numerical superiority. Despite this Görgei agreed to follow the government's plan, in order to avoid an open conflict with them.[64] So, he promised to lead his troops to southern Hungary, starting 3 July, hoping that until that day all the scattered units of his army would be able to gather and join his army.[65]

But before he had the chance to accomplish this task, Görgei's troops were attacked on 2 July at Komárom by Haynau's force, which was twice the size of his, reinforced by Panyutyin's Russian division. Görgei defeated them, upsetting Haynau's plan to quickly conquer the capitals. However, at the end of the battle, Görgei sustained a severe head wound: a shell splinter shot by an enemy cannon made a 12-centimeter (4.7 in) long cut in his skull, opening it and leaving his brain exposed. Despite this he remained conscious, led his troops until the end of the battle, only after which he fainted, losing consciousness for several days, during which time he underwent several surgeries, which prevented him from taking advantage of his victory.[66]

Before the battle, because of a misunderstanding, Kossuth removed Görgei from the command and demanded that he go to Pest, naming Lázár Mészáros, the former minister of war, who was a weak general, in his place.[65] When Mészáros went towards Komárom to inform Görgei of the change, he heard along the way the sound of the cannonade of the battle of Komárom, and returned to Pest.[1] The cause of Kossuth's drastic act was as follows. Görgei on 30 June, wrote two letters to Kossuth. In the first he reaffirmed his decision to remain with the main Hungarian forces in Komárom and fight a decisive battle against Haynau. The second letter he wrote later that day, after a meeting with a government delegation, who came with the order for Görgei to leave Komárom and march towards Szeged, in southern Hungary. In this letter, as shown before, he agreed to follow the governments new order. Görgei's two letters were sent on the same day, Kossuth did not notice their registration number, but he read the letters in the wrong order, reading the second one (in which Görgei had written that he would march towards Szeged) first, then the first letter (in which Görgei had written that he would engage in battle at Komárom) second. Thinking that Görgei had changed his mind, and had chosen not to obey the order directing the concentration around Szeged, and probably remembering Görgei's refusal in the winter campaign to follow his orders and the Proclamation of Vác of 5 January, which he considered an act of revolt, and Görgei's critique of the dethronement of the Habsburg dynasty issued by Kossuth on 14 April 1849, the Kossuth called Görgei a traitor and removed Görgei from command, and demanded that he come to Pest to take over the war ministry and let Mészáros lead the army.[65]

Because Mészáros returned to Pest, Görgei did not learn about his removal from command; and, because of Haynau's attack on 2 July, he had to postpone temporarily the retreat towards Szeged, being forced to enter in battle with the enemy. The letter containing Görgei's removal arrived on 3 July, while Görgei was unconscious from his wound. His officers, led by György Klapka, were against the decision to remove their chief.[8] Kossuth came to understood that Görgei had not disobeyed him, but he lacked the courage to admit his mistake and rescind Görgei's dismissal. Görgei remained the commander of the northern Danube army until he had the opportunity to hand it over, which meant until he would arrive at the concentration at Szeged,[8] but he resigned as Minister of Defence.[67] The disastrous military events that unfolded at the beginning of August in southern Hungary, where he was to lead his army, restored Görgei's reputation somewhat. On the other hand, Kossuth's silence regarding being mistaken about Görgei cast a shadow on the reputation of the politician.[8]

– Red: Russian army, red ⚔: Russian victory

– Black: Hungarian army, black ⚔: Hungarian victory

Klapka, the senior officer who took over the invalided Görgei's duties, was reluctant to act on the government's order to lead the troops to southern Hungary. He decided to lead an attack against Haynau's forces, hoping to defeat them; but in the Third Battle of Komárom on 11 July, the troops led by Klapka suffered a defeat. The not-fully-recovered Görgei watched the battle from the fortress. The result of this battle was that Görgei, who soon took the command of his army, was forced to retreat eastwards and let the capitals fall again into enemy hands.[68] The Hungarian parliament demanded that the government re-appoint Görgei to supreme command, but Kossuth and prime minister Bertalan Szemere, because of their hatred and envy of Görgei, appointed and dismissed, one after another, Lázár Mészáros, Henryk Dembiński, and Mór Perczel, as they failed to oppose Haynau's advance.[1]

Leaving the capitals, Görgei managed to stop the greatly superior forces of the main Russian commander Ivan Paskevich in the second battle of Vác on 15–17 July,[69] although he was suffering because of his head wound, and underwent a surgery on his skull on the second day of the battle.[70] Then, because his way to south, towards Szeged, was blocked by the Russian army, he retreated to the northeast, in almost the same way as he had done in the winter of 1848–1849, luring after himself the five-times-greater Russian forces,[64] diverting them for almost a month from attacking the main Hungarian troops on the Hungarian plain. He accomplished this through forced marches (40–50 km per day), avoiding the Russians' repeated attempts to encircle him or to cut him from the main Hungarian troops in southern Hungary.[71] Using a roundabout mountain route, Görgei managed to arrive in Miskolc before the Russians, who used a shorter route through the plain between the two cities.[1] After successfully defending the Hungarian positions along the banks of the Sajó and Hernád rivers, Görgei heard that the Russian troops had crossed the Tisza river and were heading towards the main Hungarian army in the south. Görgei again, using a much longer route, marched round the Russian army, outran them, and arrived in Arad four days before them.[1]

During his march through Northern Hungary, Görgei defeated the Russian troops in seven defensive engagements:[64] (Miskolc, 23–24 July;[72] Alsózsolca, 25 July;[73] Gesztely, 28 July;[74] etc.); losing only one, Debrecen, 2 August. This slowed the Russian advance and won time for the rest of the Hungarian army to prepare itself for a decisive battle, creating the opportunity for the supreme commander to defeat Haynau's Austrian forces, which his troops were equal to in numbers.[64]

Czar, Nicholas I of Russia was impressed by Görgei's brilliant manoeuvers, comparing him twice to Napoleon,[75] writing this to Paskevich:

The fact that Görgei, after retreating from Komárom, got first around our right then around our left-wing, making such a huge circle, then he arrived south and united with the main troops, blows my mind. And he managed to do all these against your 120,000 brave and disciplined soldiers.[76]

With Russian intervention, the cause of Hungarian independence seemed to be doomed. As a last try to save it, the Hungarian government tried to enter into negotiation with Paskevich, attempting to lure him with different proposals that conflicted with Austrian interests, one of them being to offer the Holy Crown of Hungary to the Russian Czar or to a Russian prince. But the Russian commander declared that he came to Hungary to fight and not to negotiate with politicians, and that he would discuss only the unconditional surrender of Hungary, which meant that he would not talk with politicians but only the leaders of the Hungarian army.[1] So, with the knowledge and encouragement of the Hungarian government, Görgei began negotiations with the Russian commander regarding an eventual Hungarian surrender. So, during his operations against and battles with the Russians, he also negotiated with Paskevich and his generals, to obtain favorable conditions from them, or to start a conflict between the Austrians and the Russians. All the while Görgei kept the Hungarian government informed (there were unfounded rumors about an alleged Russian plan to hire Görgei and his generals for the Russian army).[77] But the Russian commander responded that they would talk only about unconditioned surrender.[78]

In spite of Görgei's successes, in other theaters of operation the other Hungarian generals were not so successful. Dembinski, after being defeated on 5 August in the Battle of Szőreg by Haynau,[79] instead of moving his troops north to Arad—having been asked to do this by the Hungarian government,[80] to join with Görgei, who had won his race against the pursuing Russians, and together engage in a battle against Haynau—he moved south, where the Hungarian main army suffered a decisive defeat in the Battle of Temesvár on 9 August.[81] Thus, Dembinski's decision prevented Görgei from taking part with his 25,000 troops in the decisive battle. After this defeat, Kossuth saw the impossibility of continuing the struggle and resigned from his position as regent–president.[82]

On 10 August 1849. Görgei and Kossuth met for the last time in their lives at Arad. During their discussions, according to Görgei, Kossuth said that he would commit suicide, but the general convinced him not to do this, to escape and take refuge in another country, and, using the reputation that he had won as the leader of the revolution, to fight for Hungary's cause there.[83] From Görgei's declarations from that period, and also from his later writing, we can understand that he wanted to become Hungary's only martyr, hoping that this would save his country from other retributions.[1] Kossuth then handed over all political power to Görgei, giving him the title of dictator, while he and many of his ministers, politicians, and generals went south and entered Ottoman territory, asking for refuge.[82]

As in the spring campaign, in the summer campaign Görgei's personal intervention on the battlefield was crucial in the important battles, preventing defeat (as in the second battle of Vác) or even bringing about victory (as in the second battle of Komárom). From the three Hungarian operational plans elaborated during the summer campaign two were made (the plan of the concentration around Komárom) or decided in haste (the plan of the pincer maneuver towards the northeast after the second battle of Vác) by him, and both were strategically correct. His presence on the battlefield could intimidate a numerically far superior enemy, such as when his troops were stationed around Komárom, Haynau could not move towards Pest, or when he campaigned through northern Hungary, Paskevich's main forces could not move towards Szeged.[84] During the summer campaign, Görgei reached his peak as a military commander. His last campaign in northern Hungary against the five-times-larger Russian main force can be regarded as a tactical masterpiece, due to his audacious decisions, quick troop movements, rapid forced marches around and between enemy troops—outrunning them, winning several-days' distance, cleverly slipping out at the last moment from enemy encirclements—perfectly chosen positions, surprising counter-strikes, and accomplishing all this with a sizeable army, show us a great military tactician, unique among the Hungarian generals of the Freedom War.[1]

Surrender at Világos/Nagyszöllős

[edit]On 11 August, Görgei gathered his officers in a military council about what to do next. The council almost unanimously (excepting two officers) decided that the only option in the grave situation they faced was to surrender to the Russian army, because they hoped for milder conditions from the Russians than from the Austrians.[1]

Görgei was of the same opinion as his officers. He thought that if he surrenders to the Austrians, they would show no mercy to his troops and officers. He believed that surrendering to the Russians, would lead to the czar asking Franz Joseph I to pardon them; and his hope was supported by the promise of Paskevich, who declared that he would use all his influence in this matter. Görgei thought that the surrender to the Russians would save his troops, and the only man executed by the Austrians would be himself. Görgei declared that he was ready to accept this sacrifice in order to save the others.[1] He also believed that he would be able to convince Paskevich to ask mercy for the people of Hungary too.[1] Görgei thought that if he surrendered to the Austrians, he would give the impression to the world that the Hungarian revolution was an unlawful uprising, and the rebels had surrendered to their lawful ruler. The surrender to the Russians symbolized the rightful protest of the Hungarians against the oppression of Hungarian freedom by the united armies of two of the world's most powerful empires; and although Austria's and Russia's numerical and technological superiority emerged victorious, the Hungarians didn't renounce their ideal of national freedom.[1]

Days before the surrender Görgei wrote a letter to the Russian general Theodor von Rüdiger, in which he presented his wish to surrender to the Russian general, whom he respected very much for his bravery and military talent, explaining, among other things, why he decided to surrender to the Russian troops and not the Austrians:

You will agree with me, when I declare it solemnly, that I prefer to let my army corps to be destroyed in a desperate battle by a no matter how much superior army, than to put down my weapons in front of such an enemy [the Austrians], who we defeated so many times, and almost at every turn.[85]

On 11 August, Görgei sent his envoys to Rüdiger with his offer to surrender, saying that he would bring his troops to Világos. On 12 August, Görgei arrived with his troops in Világos, and was housed in the mansion of Antónia Szögény Bohus. Here he was visited at noon of the same day by Rüdiger's military envoys, which whom he agreed about the place and time of the surrender, and to prevent any Austrian presence at the surrender. The Russian Lieutenant Drozdov, who was present on the discussions at Világos wrote a description of Görgei:

Görgei looked 25. Tall, svelte, harmoniously proportioned man. His mustache was sparse, his face surrounded by a short beard, showed a gentle and kind character. The mysterious look of his big, lustrous blue eyes denoted that he was aware of his power and superiority. A bandage was bound on his head: a bright silk scarf, one corner of which covered his upper head, while the other corner fell back on his shoulder, covering the wound from the back of his head. His gentle, amiable face looked even more delicate. His clothing was as it follows: a simple dark brown attila with red lacing and trimmings on its collar, and his constant companion: a small leather bag slung over his shoulders, on his feet huge boots (which ended way over his knees) made of the coarsest leather. His speech was simple: his resonant voice showed a strong will. You could feel on his appearance and voice that he was born to command...[1]

During the discussions, Görgei pointed out that the Russian troops should position themselves between Görgei and the direction from which an Austrian advance could be expected.[1] On 11 August, he wrote to Rüdiger that it was out of the question for him to surrender in front of Austrian troops, and he would rather fight until the total annihilation of his army, and his death in battle, instead of surrendering in front of Austrian units.[1]

In the morning of 13 August, the Hungarian troops (29,494 soldiers, 7,012 horses, 142 guns, and 23,785 rifles, with only 1.5 cartridges per rifle remaining)[86] in the meadows at Szöllős surrendered (not at Világos as is often believed). The soldiers put down their arms, and the hussars tearfully said farewell to their horses. Then General Rüdiger rode to the ranks of Hungarian soldiers and officers and reviewed them.[1] After the Russian general left, Görgei rode to his soldiers, who all shouted: Long live Görgei! Hearing this the Hungarian general wept. The army then shouted repeatedly Farewell Görgei![1]

On the next day Rüdiger held a dinner for Görgei and the Hungarian officers, warmly praising their bravery and raising his glass to them. But that evening, Görgei was separated from his army and brought to Paskevich's headquarters in Nagyvárad. The commander of the Russian army received him courteously, but told him that he can assure him only his life, while the Austrians will decide about the fate of the other officers and soldiers of his army. Görgei argued that his army and officers bore no fault, they only followed his orders, and thus he was the only one who bore every responsibility for their actions; but Paskevich replied that he could not do anything, promising only that he would advocate on their behalf.[1] The Russian commander indeed wrote letters to Field Marshall Haynau, Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg the minister-president of Austria, and to Franz Joseph I, and even Czar Nicholas I wrote a letter to the emperor, trying to convince them to be merciful; but the answer was that the current situation necessitated bloodshed.[1] Their answer was that Görgei would not be court-martialed and executed, and would be kept in confinement at Klagenfurt; but they did not pardon his generals, who were executed on 6 October 1849 at Arad. After of the execution of his generals, Görgei was accused by the Hungarians of betraying them, and of causing their deaths.[87]

After the Revolution

[edit]Exile in Klagenfurt

[edit]The Austrians brought Görgei and his wife, Adéle to Klagenfurt, where he lived, chiefly employed in chemical work,[88] under constant and strict police supervision, being prohibited from leaving the town and its surroundings.[89]

Later, from a part of his wife's inheritance, Görgei bought a house in the village of Viktring, near Klagenfurt; with hard work he started a garden and started to grow vegetables and fruits to feed his family.[90]

Görgei, in order to assure an income, thus freeing himself and his family from the dependence of the Austrian subsidy, decided to write a book about his role in the Hungarian Freedom War. He spoke with the Viennese publisher Friedrich Manz, who agreed to print the book. Görgei wrote his book with the knowledge of the Austrian secret police. The Austrians hoped that Görgei, looking for milder treatment from them, would write a book that would criticize Kossuth, their enemy in exile, and present the Habsburgs in a positive light. But Görgei's work Mein Leben und Wirken in Ungarn in den Jahren 1848 und 1849 (My Life and Works in Hungary in the Years 1848 and 1849) didn't show any moderation when it came to the Austrian government and military leadership, listing their weaknesses, errors, and inhuman policies. When Manz read the manuscript, he understood after the first pages that this book could not be published in Austria, because the state censorship would not allow it. So Manz smuggled the manuscript to the Kingdom of Saxony, to Leipzig, where the F. A. Brockhaus AG published the book in the summer of 1852. When the Austrian authorities learned about the book and its contents, they were outraged, many of the Austrian politicians and military leaders whom Görgei presented a negative way (among them Windisch-Grätz), demanding his punishment; and the Police Minister, Johann Franz Kempen von Fichtenstamm, was eager to start a prosecution against Görgei, who was forced by Austria's agreement with the Russians from 1849 to renounce the book. Manz was arrested and sent to prison, and all the books that had been brought into the Habsburg Empire were destroyed.[1]

Unlike Artúr Görgei, his wife and his children, who were born in exile, could move wherever they wanted. So, in 1856–1857 Adéle and the children went to Hungary, staying a year at Artúr's younger brother, István in Pest, and in Szepes county with other relatives of Görgei.[89]

On another occasion, Adéle and their daughter Berta, went to Paris to see her relatives; and Görgei, knowing that the son of one of Adéle's sister, Edouard Boinvillers, was a confidant of Napoleon III, gave to Adéle a memorandum, in which he tried to convince the French emperor that Kossuth and his entourage of Hungarian politicians and officers in exile have contrary interests, and that in his opinion Napoleon should support a Hungarian-Austrian compromise. After reading Görgei's memorandum, Boinvillers wrote to him, asking some questions, and Görgei replied quickly; but it seems that the memorandum was never forwarded to Napoleon III.[89]

Görgei paid close attention to the political developments in Hungary, reacting to every important event of Hungarian politics. The main cause of this was that Görgei believed that he could return to Hungary only if the oppressive Austrian policy towards Hungary would be relaxed, and that moderate Hungarian politicians would take the lead in Hungary. He was filled with hope when he heard about the moderate politics of Ferenc Deák. He started to look to Deák as his future savior from his exile. He photographed himself with a copy of the Hungarian newspaper Pesti Napló, which published Deák's petition about the necessity of a compromise with the Austrians, if they accept the April Laws of the Hungarian Revolution as the basic laws of Hungary.[89] In one of his letters to Gábor Kazinczy, one of the former leaders of Peace Party, from 1848 to 1849, Görgei wrote that he had the portraits of István Széchenyi and Ferenc Deák (the two most proeminent Hungarian moderate politicians) on his desk.[89] He wrote an article in Pesti Napló in which he asked Hungarians to compromise with the Austrians, while demanding that the latter accept the Hungarian laws enacted from 1847 to 1848.[89]

At the end of 1863, Görgei sent his wife and children to Hungary, and his son to a Hungarian public school. He hoped that his wife would have the opportunity to get acquainted with Hungarian politicians, and other important persons, whom she would convince to support her husband's return to Hungary. But many of these politicians, as a result of Kossuth's false accusations of treason, were unsympathetic. She still found some who did not believe Kossuth's accusations—such as Antónia Bohus-Szőgyény, in whose castle near Világos Görgei, on 13 August 1849, signed the surrender of the Hungarian army—and politicians who were ready to support his return, such as Sr. László Szögyény-Marich, Baron Miklós Vay (royal commissioner of Transylvania from 1848), Ágoston Trefort (court chancellor, 1860–1861), and Béni Kállay. She met also with the wholesaler Frigyes Fröhlich, a friend of Görgei's father, who presented her and her children to Ferenc Deák, who was sympathetic with Görgei's wish to return home. She assured Deák that Görgei's political views were similar to his, and if he could come home, would support him in every way. She also begged him to fight against the false accusations of high treason of which Görgei was accused by a large part of the Hungarian people.[89] In 1866, Görgei's younger brother, István, also sent him encouraging news about another politician whom he knew from 1848 to 1849, Pál Nyáry, who was sympathetic to Görgei's cause, and believed that after the Hungarian-Austrian compromise, he would return, and his image in Hungary would also improve.[89]

Beginning in 1862, Görgei had a fellow Hungarian in Klagenfurt, László Berzenczey, a radical politician of the 1848–1849 independence movement, who, after returning from\ exile, was interned in Klagenfurt. He and Görgei argued daily about Hungarian internal politics, including Ferenc Deák's domestic policies: Berzenczey being very critical of them, while Görgei defended Deák's policies.[89]

When the Austro-Prussian War broke out, Görgei declared that he was afraid of Kossuth's interference in Hungarian politics from outside, and that he was against any idea of a Garibaldist revolution against the Austrians, which, in his opinion, Kossuth wanted to start, to liberate Hungary with French help.[89] After the Austrian defeat at the Battle of Königgrätz, and the Peace of Prague, the chances of a Hungarian-Austrian compromise started to materialize.[89]

Army reform proposals

[edit]As a result of the 1866 battle of Königgrätz being lost by the Austrians, the probability of a Hungarian-Austrian compromise was increased. Görgei was asked by his old friend from the War of Independence, Imre Ivánka, now a member of the Hungarian parliament, to give his opinion on the bill about general liability for military service of the Hungarian military units, and their unification into a common army. The bill was to be issued as law after an eventual compromise. Görgei started to work on this, and finished it in the first months of 1867, sending it to Deák.[89]

At the beginning of the 31-page manuscript Görgei expressed his fundamental ideas as follows:

- To keep the system of recruitment by counties;

- To avoid provoking the anger of the Austrian military command in achieving the goals of the Hungarian army reform;

- To awake again Hungarian sympathy for the army, which was lost after the defeat of the War of Independence, and convince them to become soldiers;

- To make it possible for soldiers to marry earlier, removing the bureaucratic obstacles that prevented this, and allowing it as virtuousness;

- To accustom the Hungarian youth to learn and study, and to think of the public good at an early age;

- To increase the defense power of Hungary to the highest level.[89]

Görgei criticised a proposed law that would diminish the Hungarian war ministry's responsibility for the internal organization of the Hungarian army. He believed that this would endanger the ability of the emperor to control the army. He proposed instead that the Hungarian and Austrian war ministries put forward a joint proposal on the national defense to the ministry council, to be legislated.

Secondly, Görgei pointed out that the cause of the defeat of the imperial army against the Prussian troops in 1866 was caused by the shortage of weapons and manpower, as well as poor organization of defense forces. He pointed to the fact that the Prussians had mostly modern breech-loading rifles, while the Austrians still used outdated muzzle-loading rifles. It had been a mistake to send troops over an open field to charge the Prussian soldiers, protected by trenches, who, with their breech-loading rifles caused catastrophic damage.[89] Based on contemporary sources, Görgei concluded that the Austrians were numerically superior in the majority of the battles, but the outdated weapons and the wrong tactics used by them, led to their defeat.[89] Görgei's opinion was that it was not numbers of soldiers that determined the strength of an army, but their love of and attachment to their country.[89]

In the third part of the memorandum, Görgei criticized the bill in question, which proposed to recruit, and to put under military jurisdiction, all men who turned 20–22 for 12 years, thus preventing young intellectuals during their most productive ages, to exercise their political rights and duties. He wrote that with this bill the government wants to neutralize "the Hungarian intellectuals with democratic political credo".[89]

Görgei proposed the following:

- In the regular army the men must serve six years, the first and the second reservists three years. Liability for service in the national guards, as well as those who had to participate in the "general uprising" (when the country was attacked and it was in grave danger, it was a Hungarian tradition that the nobles "upraised", gathered together and fought the enemy; after 1848, not only the nobles had to uprise but all the nation).[91] would continue until the age of 45;

- The most important duty of the army in peacetime must be the military exercises of the recruits and reservists. This training should be conducted every autumn. During these military exercises, soldiers must remain under civil law. Besides this, the armed units should perform a "ceremonial general national review".

- The regular army should be composed of the volunteers, recruits, soldiers on leave, those who are conscripted as punishment, and students of military academies. The recruits who can read and write, can prove their unimpeachable character, are peasants, work on their parents' land, are craftsmen or merchants, are civil servants or junior clerks, are enrolled in the university or courses of equal value will serve only a year. The people who are not in these categories, will serve two years.

- If the old traditions of harsh military discipline must be relaxed, and educational opportunities in the army increased, because this will convince more and more young people to join the army and make possible a volunteer army.

- The parliament has the responsibility of recruiting troops, if the number of the volunteers is not enough, and in special cases it must conscript soldiers for three years of service.

- The military companies and regiments must remain in the countries in which they were conscripted. And the king has to send home all Hungarian troops that were brought outside of Hungary.

- Regimental districts, whence each regiment will receive its recruits, should be the same as the parliamentary electoral districts.

- The right that somebody liable for service could pay a substitute to take their place must be abrogated.

- Those in military service must be compensated by a specified amount of money.

- Volunteers and recruits under 21 can choose the branch of service in which they want to serve.

- Military education should be introduced in the high schools.

- In case of war, all units must be a part of the army, the first reservists included, while the second reservists will assure the defense of the hinterland. If needed, also the National Guards and the National Insurrection must be called to duty. The clerks, civil servants, those who assured order and the security (police, firemen, etc.), as well as those who work in the transport, catering service, and education, must be exempted.[89]

At the same time as Görgei, also Klapka, Antal Vetter, and Imre Ivánka made their memorandums on the reform of the Hungarian army. When Count Gyula Andrássy went to the debates about the future military organization of Austria-Hungary, the Hungarian plan included Görgei's modern "intellectual-friendly" and pro-socialization views. Görgei's proposition about the right of the Hungarian parliament to decide the recruitment of the new troops, and the remaining of the recruits and reservists, during their military exercises, under the civil law, entered in the future Law of the Defense of Hungary.[89]

Return to Hungary

[edit]

After the Austro-Hungarian compromise of 1867, it was well known that an amnesty would be promulgated for Hungarian soldiers and politicians, and this meant a chance for Görgei to finally return home. Although he wanted very much to return, Görgei was pessimistic about this.[90] His brother, István, proposed to ask Ferenc Deák to help Görgei to obtain permission to return, but István said that he considered that the constitution would be considered as restored in Hungary only after the coronation of Franz Joseph as King of Hungary, so he believed that only after that event would he be granted leave to return. István also pointed out that, for the time being, Görgei's only income was the subsidy he received from the Austrian government, which would stop if Görgei would go back to Hungary. István told Görgei that he must find a job in Hungary to sustain his family, before he returned, because he would not want to live on the charity of others.[89]

On 9 June 1867, the amnesty was granted; but when he read its text, Görgei didn't find in it any reference to what would happen to somebody in his situation. He thought that those politicians who formulated the text of the amnesty deliberately omitted him, in order to prevent his return. He even heard about the words of Ferenc Pulszky, one of Kossuth's closest friends, newly returned from exile, who said about him: "Let him [remain] there [in Klagenfurt]".[89]

Before 20 June, Görgei's wife, Adéle Aubouin, had an audience with the new Hungarian prime minister, Gyula Andrássy.[90] She asked him if her husband had received amnesty or not? Andrássy replied that he did not know anything about this, because the amnesty was the king's decision; but he promised that he would ask the Austrian prime minister, Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust, about this.[89] During this time, Görgei's daughter Berta married László Bohus, the son of Antónia Szögény Bohus, his hostess when he signed the surrender of the Hungarian army at her castle near Világos.[89]

Finally, on 16 July, the chief of police of Klagenfurt announced to Görgei that his internment had ended, and that he could return to Hungary. On 19 July, the day on which he received the official decision of his amnesty, he took the train to Hungary.[89]

Revolution scapegoat

[edit]In the military council held in Arad on 11 August 1849, two days before he surrendered to the Russians, Görgei made a speech in which he foresaw that he would be regarded as a traitor to his nation for his surrender:

My friends! I foresee the fact that, because of their infatuation, or because they do not know the immense misery in its entirety, maybe millions who cannot size up the situation, that without any aid we are too weak to defend our fellow-citizens and their rights – I say millions will accuse me of treason. Despite that I know that maybe already tomorrow somebody, blinded by hatred, will take a weapon in his hands to kill me, with a firm conviction, and, believing that any further bloodshed is harmful, I still consider and beg you all [the officers in his army], who cannot be accused of cowardliness, to reflect about my proposal [to surrender], which, before long, can bring at least the peace to our country in dire straits.[92]

The surrender, and particularly the fact that his life was spared while his generals and many of his officers and men were hanged or shot, led to his being accused of treason by public opinion.[44] The main cause of these accusations was a letter written on 12 September 1849 by Kossuth, from his exile in Vidin, declaring unfairly that Görgei had betrayed Hungary and its nation when he laid his weapons down.[1] In his letter Kossuth wrote: "...I uplifted Görgei from the dust in order to win for himself eternal glory, and freedom for his fatherland. But he cowardly became the executioner of his country."[93]

The accusations made by Kossuth's circle against Görgei were:

- From the beginning of his career as a general, Görgei wanted to be a dictator;

- He organized a camarilla around him;