Artaxias I

| Artaxias I | |

|---|---|

| King of Armenia | |

Possible coin of Artaxias I | |

| King of Armenia | |

| Reign | 189 – 160 BC |

| Predecessor | Orontes IV |

| Successor | Artavasdes I |

| Died | 160 BC Bakurakert, Marand, Kingdom of Armenia |

| Issue | Artavasdes I of Armenia Tigranes I Vruyr Mazhan Zariadres |

| Dynasty | Artaxiad dynasty |

| Father | Zariadres |

Artaxias I[a] (from Ancient Greek: Άρταξίας) was the founder of the Artaxiad dynasty of Armenia, ruling from 189 BC to 160 BC. Artaxias was a member of a branch of the Orontid dynasty, the earlier ruling dynasty of Armenia. He expanded his kingdom on all sides, consolidating the territory of Greater Armenia. He enacted a number of administrative reforms to order his expanded realm. He also founded a new capital in the central valley of the Araxes River called Artaxata (Artashat), which quickly grew into a major urban and commercial center. He was succeeded by his son Artavasdes I.

Name

[edit]The Greek form Artaxias ultimately derives from the Old Iranian name *Artaxšaθra-, which is also the source of Greek Artaxérxēs (Αρταξέρξης) and Middle Persian Ardashir.[2][3][1] The Armenian form of this name is Artašēs (Արտաշէս)․ It was borrowed into Armenian at an early date, possibly during the late Achaemenid period, from Old Persian Artaxšaçā.[4] According to Hrachia Acharian, the immediate source of the Armenian form is the unattested form *Artašas.[1] The name can be translated as "he whose reign is through truth (asha)."[2][3] In his Aramaic inscriptions, Artaxias refers to himself with the epithet "the Good," which, in Gagik Sargsyan's view, should be understood as "the Pious," corresponding to the Greek epithet Eusebḗs.[5] In Armenian historiography, he is sometimes referred to by the epithets "the Pious" (Բարեպաշտ, Barepasht) and "the Conqueror" (Աշխարհակալ, Ashkharhakal).[6]

Background

[edit]Armenia was ruled by members of the Orontid dynasty, probably of Iranian origin, starting from the 5th century BC.[7] At the end of the 3rd century BC, the Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great (r. 222 – 187 BC) appointed Artaxias and Zariadres as strategoi (military governors) of Greater Armenia and Sophene, respectively. The Greek geographer Strabo reports that Artaxias and Zariadres were generals of Antiochus III.[8] However, the discovery of boundary stones with Aramaic inscriptions in Armenia in which Artaxias proclaims himself to be an "Orontid king" and "the son of Zareh (Zariadres)" has proven that Artaxias and Zariadres were not Macedonian generals from outside of Armenia but members of the local Orontid dynasty, albeit probably belonging to different branches than the original ruling house.[9][b] Different views exist on the question of whether the Zareh mentioned in Artaxias' Aramaic inscriptions is identical with the Zariadres who became ruler of Sophene according to Strabo. Michał Marciak argues that identifying Zariadres of Sophene with the Zareh of the inscriptions seems to be "the most straightforward interpretation."[11]

Strabo's information that the last ruler of Armenia prior to Artaxias' arrival had been named Orontes (the most common name of the rulers of the Orontid dynasty) corresponds with the semilegendary account of the later Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi, who writes that the Armenian king preceding Artaxias was Eruand (i.e., Orontes), who was defeated and killed in his war with Artaxias for the throne of Armenia. Also matching with this evidence are two inscriptions found at the Orontid capital of Armavir which mention a king named Orontes and lament the death of an Armenian ruler killed by his own soldiers.[7] While there are still questions about the dating of the Armavir inscriptions,[12] this evidence has been used to support the view that Artaxias, a local dynast, overthrew the Orontid king Orontes IV (r. 212 – 200 BC) at the instigation of Antiochus III.[13] Movses Khorenatsi presents the following account of Artaxias' battle with Orontes, which, in Robert W. Thomson's view, is an adaptation of the battle between Alexander and Darius in the Alexander Romance:[14] Artaxias marched into Armenia through Utik and defeated Orontes' army at Eruandavan, located near the northern Akhurian River. Orontes then took refuge in his capital, Eruandashat, which was besieged by Artaxias' ally Smbat, later joined by Artaxias. The city was taken, and Orontes was killed by a soldier.[15]

Soon after Antiochus was defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Magnesia in 191/190 BC, Artaxias and Zariadres revolted against the Seleucids and declared themselves independent kings in Greater Armenia and Sophene.[10][16][12][8] In 188 BC, Artaxias and Zariadres were recognized by the Roman Senate as independent rulers.[17]

Reign

[edit]

After gaining their independence from the Seleucids, Artaxias and Zariadres, who may have been close relatives, allied with each other to expand their dominions.[19] Their conquests were not obstructed by the Seleucids during the reign of Antiochus' successor Seleucus IV (r. 187 – 175 BC), who decided not to wage any new wars.[20] The kingdom of Artaxias, originally centered around the Araxes valley, expanded into Iberian land and especially the territory of Media Atropatene, which lost its territories bordering the Caspian Sea.[19] The Kura River became the northern and northeastern border of Greater Armenia.[21] Strabo reports that Artaxias also conquered from Atropatene the districts of "Phaunitis" and "Basoporeda," perhaps corresponding to Siwnikʿ and Vaspurakan (alternatively, Parspatunik),[22] respectively.[19] Meanwhile, Zariadres conquered Acilisene.[19] Another territory mentioned by Strabo, read as either Taronitis (i.e., Taron) or Tamonitis (either Tman[23] or Tmorik[22]), was conquered either by Zariadres[19] or Artaxias.[22][c] According to Strabo, the unification of these territories under Artaxias and Zariadres led the population of Greater Armenia and Sophene to "speak the same language," i.e., Armenian.[24][d] However, the imperial Aramaic inherited from the Achaemenid Empire continued to be the language of the government and the court.[19] Like the monarchs of Pontus and Cappadocia, Artaxias and his successors preserved the royal traditions used by the former Achaemenid Empire.[19] At the same time, Greek influence was starting to advance in the country.[19] Eventually, Aramaic would be phased out and replaced with Greek as the court language.[28]

According to the Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi, Artaxias ordered the delimitation of villages and farmland; this has been confirmed by the discovery of boundary stones with Aramaic inscriptions in Armenia.[19] Artaxias founded the city of Artaxiasata (from Artaxšas-šāt, "the joy of Artaxias," abbreviated to Artaxata in Greek and Artashat in Armenian)[21] on the left bank of the Araxes River, which served as the capital of Armenia until the 2nd century AD.[19] Strabo and Plutarch report that the former Carthaginian commander Hannibal took refuge at the Armenian court and played a role in the establishment of the city, although this is unlikely to be true.[19] Khorenatsi reports that Artaxias resettled residents from Eruandashat and Armavir to Artaxata and transferred the idols of Tir, Anahit, and various other statues from Bagaran. The statue of Tir was placed outside the city near the roads.[29][e] The result of these policies led to the quick development of Artaxata, which became an important administrative, commercial, cultural, and religious center. Artaxias also founded the city of Arxata, which was mentioned by Strabo, as well as the cities of Zarehavan and Zarishat, which were both named after his father, Zariadres.[31]

By 179 BC, Artaxias had become so powerful from his conquests that he was able to act as a mediator in the conflicts of the rulers of Asia Minor. However, his plan to annex Sophene failed.[16] According to Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC), at some point during the reign of Zariadres' successor Mithrobouzanes, Artaxias proposed to Ariarathes II of Cappadocia to kill the princes of Sophene at their respective courts and partition Sophene between themselves, but this proposal was rejected.[32][f] In 165/4 BC,[34] Artaxias was defeated and briefly captured by the forces of the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175 – 164 BC), apparently recognizing Antiochus' authority to secure his release.[35] However, this does not appear to have affected his control over Greater Armenia.[21][g] In 161/0 BC, Artaxias managed to help the satrap of Media, Timarchus, who had rebelled against Seleucid rule.[19] Artaxias died in approximately 160 BC and was succeeded by his son Artavasdes I.[10][21]

Coinage

[edit]

Unlike their predecessors, the Orontids, the majority of the Artaxiad rulers minted coins. Frank L. Kovacs has attributed a number of coins to the reign of Artaxias I, eight with Aramaic and four with Greek inscriptions.[28] However, Ruben Vardanyan and Karen Vardanyan have attributed most of these coins to the later king Artaxias II.[37][38] The first coins depicting Artaxias bear the Aramaic inscription "King Artashes" (Imperial Aramaic: 𐡀𐡓𐡕𐡇𐡔𐡎𐡉 𐡌𐡋𐡊𐡀, romanized: rthṣsy mlk) and have depictions of a dog (likely an Armenian Gampr), a bee, the head of an unknown bearded male, an eagle, and the head of Antiochus IV. Later coinage dropped the use of Aramaic and transitioned to Greek inscriptions (Ancient Greek: Βασιλεως Αρταξερξου, romanized: Basileus Artakserksou). These coins also depicted the cornucopia, grapes, and a club on the reverses. Artaxias is always depicted as bearded and wearing his five peaked Armenian tiara, with the exception of one coin depicting him wearing a Phrygian cap with a fanion and lappets.[28]

Family

[edit]According to an epic tradition related by Movses Khorenatsi, Artaxias married Satenik, daughter of the king of the Alans, as part of a peace treaty after Artaxias defeated the invading Alans on the banks of the Kura River.[39] However, it is generally believed that the real historical basis for the story came from the invasion of Armenia by the Alans in the 1st century AD, during the reign of Tiridates I.[40] Artaxias' known sons were his successors, Artavasdes I and Tigranes I.[41] Four other sons are attested only in Movses Khorenatsi's history: Mazhan, who was appointed priest of Aramazd in Ani; Vroyr, who was appointed hazarapet; Tiran, who was given command of the southern part of the army; and Zareh, who was appointed commander of the northern part of the army.[29][h]

Legacy

[edit]Artaxias in the Armenian folk epic

[edit]

Artaxias features prominently in the Armenian folk epic referred to in scholarship as Vipasank’. Movses Khorenatsi drew from this folk epic when writing about Artaxias and other Armenian kings in his history. The epic about Artaxias is based on historical events, but contains significant anachronisms and conflations of different figures and their deeds. For example, in the epic (and thus also in Khorenatsi's history) the invasion of Armenia by the Alans is placed in Artaxias' time, when it actually occurred in the 1st century AD, under Tiridates I.[46] The account of Artaxias' early life in the epic follows a pattern seen also in other epic traditions: Artaxias, who is a son of the Armenian king Sanatruk,[i] is the sole survivor of the massacre of his family by King Orontes; he is saved by his tutor Smbat Bagratuni and taken to live with shepherds (as in stories about Cyrus the Great and Ardashir I); he then returns to reclaim his kingdom with Persian help.[47] The epic relates how Artaxias married the Alan princess Satenik after fighting with the Alans, which is narrated in detail by Khorenatsi. Part of the epic also deals with Artaxias' conflict with the nobleman Argavan,[j] which is caused by his greedy son Artavazd (mainly based on the later Artavasdes II, not the actual successor of Artaxias I),[50] and the conflict between Artaxias' sons.[47] In the epic, Artaxias curses his son Artavazd from the grave to be taken away by the spirits known as k’ajk’ and imprisoned for eternity.[51] Some verses from the epic regarding the death of Artaxias are preserved in the Letters of the 11th-century Armenian scholar Grigor Magistros.[52]

Cultural depictions

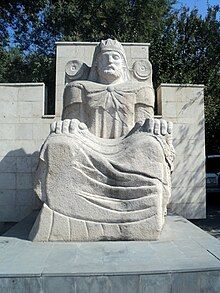

[edit]In 1848, the Armenian playwright Srabion Hekimian wrote a play in Classical Armenian titled Artashes ev Satenik (Artashes and Satenik).[53] The 19th-century Armenian poet Bedros Tourian wrote a play about Artaxias titled Ardashes Ashkharhagal (Artashes the Conqueror), which was first performed in 1870. It was written on the basis of Khorenatsi's history.[54] Artaxias has been depicted in painting by Mkrtum Hovnatanian (1836).[44] In 2001, a statue of Artaxias by Vanush Safaryan was erected in the central square of modern-day Artashat.[45]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Rendered as Արտաշէս Artashes in Armenian since the 5th century AD[1]

- ^ James R. Russell notes that Artaxias' claim to Orontid descent reflects Armenian and Iranian ideas of kingship and status, which had to be inherited by blood, not acquired.[10]

- ^ If the reading Tamonitis and its identification with Tmorik are correct, then a conquest by Artaxias is more likely, as this territory was located further east.[22]

- ^ Some authors, such as Gagik Sargsyan and Asatur Mnatsakanyan, claim that Artaxias was actually reconquering territories which were already Armenian, such as Syunik, Utik, Caspiane and Artsakh, although this was disputed by Robert H. Hewsen.[25][26] In a later work, however, Hewsen considers it possible that the Orontid kingdom extended to the confluence of the Kura and Araxes rivers.[27]

- ^ According to Thomson and Auguste Carrière, here Khorenatsi is adapting the earlier Armenian history of Agathangelos regarding the idols.[30]

- ^ Assuming, as Marciak does, that Artaxias was the son of Zariadres, Artaxias appears to have been asserting his succession rights as the firstborn son of Zariadres over the younger rulers of Sophene.[33]

- ^ Gagik Sargsyan, drawing on information about the conflict between Artaxias and Antiochus IV preserved in one of Jerome's refutations of Porphyry, concludes that Artaxias was not taken prisoner by Antiochus, and that he actually repulsed the Seleucid attack (caused by his own incursion into Seleucid territory), albeit with heavy losses. Sargsyan suggests that it was during this conflict that Artaxias conquered Tamonitis/Tmorik from "the Syrians" (understood by Sargsyan to be referring to the Seleucids), as reported by Strabo.[36]

- ^ As James R. Russell notes, the division of the army into four commands (here between Artavazd, Tiran, Smbat, and Zareh)[42] is "almost certainly" anachronistic for Artaxias' time.[43]

- ^ The name of a later Armenian king

- ^ Khorenatsi identifies the mythological Argavan with the historical prince Argam of the Muratsan dynasty,[48] which, according to Khorenatsi, was of Median origin. References to vishaps ('dragons') or vishapazunk’ ('descendants of the race of dragons') in the Armenian epic are interpreted by Khorenatsi as allegorical references to the Medes and their descendants in Armenia.[49]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Acharian 1948.

- ^ a b Schmitt 1986, pp. 654–655.

- ^ a b Wiesehöfer 1986, pp. 371–376.

- ^ Sargsyan 1966, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Sargsyan 1971, p. 538.

- ^ Hovhannisyan, Petros [in Armenian]. Արտաշես 1-ին [Artashes I] (in Armenian). Institute for Armenian Studies, Yerevan State University. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014.

- ^ a b Garsoïan 1997, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Garsoïan 2004.

- ^ Garsoïan 1997, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b c Russell 1986.

- ^ Marciak 2017, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b Facella 2021.

- ^ Lang 2000, p. 512.

- ^ Moses Khorenatsʻi 1978, p. 25.

- ^ Moses Khorenatsʻi 1978, pp. 185–187.

- ^ a b Schottky 2006.

- ^ Lang 2000, p. 513.

- ^ Karakhanian 1971, p. 275.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Chaumont 1986.

- ^ Sargsyan 1966, p. 242.

- ^ a b c d Garsoïan 1997, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Marciak 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Hewsen 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Garsoïan 1997, p. 50.

- ^ Hewsen 1982, p. 32: "Thus, it was only under Artašēs, in the second century B. C., that the Armenians conquered Siwnik′ and Caspiane and, obviously, the lands of Arc′ax and Utik′, which lay between them. These lands, we are told, were taken from the Medes. Mnac′akanyan's notion that these lands were already Armenian and were re-conquered by the Armenians at this time thus rests on no evidence at all and indeed contradicts what little we do know of Armenian expansion to the east".

- ^ Sargsyan 1976, p. 139b: "Կարճ ժամանակամիջոցում նա վերամիավորել է Երվանդունիների պետությունից մ․ թ․ ա․ III դ․ վերջին կամ մ․ թ․ ա․ II դ․ սկզբին անջատված ծայրագավառները (Կասպք, Պարսպատունիք, Գուգարք, Կարին, Տմորիք ևն)" [In a short period of time, he [Artashes] reunited the border regions detached from the Orontid state (Caspiane, Parspatunik, Gugark, Karin, Tmorik, etc.) at the end of the 3rd century BC or the beginning of the 2nd century BC].

- ^ Hewsen 2001, p. 32, maps 19, 21.

- ^ a b c Kovacs 2016, pp. 9–10, 86–87.

- ^ a b Moses Khorenatsʻi 1978.

- ^ Moses Khorenatsʻi 1978, p. 190, n. 11, 12.

- ^ Ժամկոչյան, Ա Գ (1963). Հայ ժողովրդի պատմություն (in Armenian). Հայպետուսմանկհրատ.

- ^ Marciak 2017, p. 127.

- ^ Marciak 2017, p. 158.

- ^ Chaumont 1993, p. 435.

- ^ Marciak 2017, p. 126, n. 94.

- ^ Sargsyan 1966, pp. 242–246.

- ^ Vardanyan & Vardanyan 2008, p. 92, n. 38.

- ^ Vardanyan 2001.

- ^ Moses Khorenatsʻi 1978, p. 192.

- ^ Dalalyan 2006, p. 245.

- ^ Garsoïan 1997, p. 52.

- ^ Moses Khorenatsʻi 1978, p. 196.

- ^ Russell 2004, p. 162.

- ^ a b Արտաշես Ա. թագավոր (1836). Gallery.am (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020.

- ^ a b Զրույց քանդակագործ Վանուշ Սաֆարյանի հետ [Interview with sculptor Vanush Safaryan]. Lurer.com (in Armenian). 16 October 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024.

- ^ Abeghian 1966, p. 115.

- ^ a b Russell 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Petrosyan 2016, pp. 10.

- ^ Abeghian 1985, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Russell 2004, p. 158.

- ^ Russell 2004, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Russell 2004, p. 163.

- ^ Hekimian 1857, pp. 279–281.

- ^ Tourian 1972, pp. 512–513.

Sources

[edit]- Abeghian, Manuk (1985). "Hay zhoghovrdakan aṛaspelnerě M. Khorenatsʻu Hayots patmutyan mej (Kʻnnadatutʻyun ev usvatskʻ)" Հայ ժողովրդական առասպելները Մ. Խորենացու Հայոց պատմության մեջ (Քննադատություն և ուսվածք) [Armenian popular legends in M. Khorenatsi's History of Armenia (criticism and study)]. Erker Երկեր [Works] (in Armenian). Vol. 8. Yerevan: HSSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 66–272.

- Abeghian, Manuk (1966). Erker Երկեր [Works] (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Yerevan: HSSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun.

- Acharian, Hrachia (1948). "Artashes" Արտաշէս. Hayotsʻ andznanunneri baṛaran Հայոց անձնանունների բառարան [Dictionary of Armenian given names] (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Petakan hamalsarani hratarakchʻutʻyun. p. 305.

- Chaumont, M. L. (1986). "Armenia and Iran ii. The pre-Islamic period". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/4: Architecture IV–Armenia and Iran IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 418–438. ISBN 978-0-71009-104-8.

- Chaumont, M. L. (1993). "Fondations séleucides en Arménie méridionale" [Seleucid foundations in southern Armenia]. Syria (in French). 70 (3/4): 431–441. doi:10.3406/syria.1993.7344. JSTOR 4199038.

- Dalalyan, Tork (2006). "On the Character and Name of the Caucasian Satana (Sat'enik)". Aramazd: Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2: 239–253. ISSN 1829-1376.

- Facella, Margherita (2021). "Orontids". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Garsoïan, Nina (2004). "Armeno-Iranian Relations in the pre-Islamic period". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Garsoïan, Nina (1997). "The Emergence of Armenia". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Vol. 1. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 37–62. ISBN 0-312-10169-4.

- Garsoïan, Nina (2005). "Tigran II". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Hekimian, Srabion (1857). Taghkʻ, kertʻuatskʻ ew tʻatrergutʻiwnkʻ Տաղք, քերթուածք եւ թատրերգութիւնք [Songs, poems and plays] (in Armenian).

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- Hewsen, R. H. (1986). "Artaxata". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/6: Art in Iran I–ʿArūż. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 653–654. ISBN 978-0-71009-106-2.

- Hewsen, Robert H. (1982). "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians". In Samuelian, Thomas J. (ed.). Classical Armenian Culture: Influences and Creativity. Chico, CA: Scholars Press. pp. 27–40. ISBN 0-89130-565-3.

- Karakhanian, G. (1971). "Arameeren norahayt erku ardzanagrutʻyunner" Արամեերեն նորահայտ երկու արձանագրություններ [Two newly found inscriptions in Aramaic]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes (3): 274–276. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Kovacs, Frank L. (2016). Armenian Coinage in the Classical Period. Lancaster: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. ISBN 9780983765240.

- Lang, David M. (2000). "Iran, Armenia and Georgia". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 505–536.

- Marciak, Michał (2017). Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene: Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35072-4.

- Moses Khorenatsʻi (1978). History of the Armenians. Translation and commentary by Robert W. Thomson. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39571-9.

- Petrosyan, Armen (2016). "Armianskaia Satenik/Satinik i kavkazskaia Satana/Sataneĭ" Армянская Сатеник/Сатиник и кавказская Сатана/Сатаней [Armenian Satenik/Satinik and Caucasian Satana/Sataney]. Vestnik Vladikavkazskogo Nauchnogo Tsentra (in Russian). 1: 8–17. ISSN 1683-2507.

- Romeny, R. B. ter Haar (2010). Religious Origins of Nations?: The Christian Communities of the Middle East. Brill. ISBN 9789004173750.

- Russell, J. R. (1986). "Artaxias I". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/6: Art in Iran I–ʿArūż. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 659–660. ISBN 978-0-71009-106-2.

- Russell, James R. (2004). "Some Iranian Images of Kingship in the Armenian Artaxiad Epic". Armenian and Iranian Studies. Belmont, MA: Armenian Heritage Press. pp. 157–174. ISBN 978-0-935411-19-5.

- Sargsyan, Gagik (1971). "Hayastani miavorumě ev hzoratsʻumě Artashes A-i ōrokʻ" Հայաստանի միավորումը և հզորացումը Արտաշես Ա-ի օրոք [The unification and strengthening of Armenia at the time of Artashes I]. In Yeremian, Suren; et al. (eds.). Hay zhoghovrdi patmutʻyun Հայ ժողովրդի պատմություն [History of the Armenian People]. Vol. 1. Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences. pp. 521–551.

- Sargsyan, G. (1976). "Artashes I" Արտաշես Ա. In Simonian, Abel (ed.). Haykakan sovetakan hanragitaran Հայկական սովետական հանրագիտարան [Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). Vol. 2. Yerevan: Haykakan hanragitarani glkhavor khmbagrutʻyun. p. 139.

- Sargsyan, G. Kh. (1966). Hellenistakan darashrjani Hayastaně ev Movses Khorenatsʻin Հելլենիստական դարաշրջանի Հայաստանը և Մովսես Խորենացին [The Armenia of the Hellenistic period and Movses Khorenatsi] (in Armenian). Yerevan: HSSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun. OCLC 20070239.

- Schmitt, R. (1986). "Artaxerxes". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/6: Art in Iran I–ʿArūż. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 654–655. ISBN 978-0-71009-106-2.

- Schottky, Martin (Pretzfeld) (2006). "Artaxias". Brill's New Pauly. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e202070. ISBN 9789004122598.

- Shifman, Ilya (1980). "Gannibal v Armenii" Ганнибал в Армении [Hannibal in Armenia]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Russian) (4): 257–261. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Tiratsian, G. (1976). "Artashat" Արտաշատ. In Simonian, Abel (ed.). Haykakan sovetakan hanragitaran Հայկական սովետական հանրագիտարան [Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). Vol. 2. Yerevan: Haykakan hanragitarani glkhavor khmbagrutʻyun. pp. 135–136.

- Tourian, Bedros (1972). Erkeri zhoghovatsu Երկերի ժողովածու [Collected works] (in Armenian). Vol. 2. Yerevan: HSSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun.

- Vardanyan, Karen (December 2001). "A dated copper coin of Artaxias II: Evidence on the use of the Pompeyan Era in Artaxata" (PDF). Armenian Numismatic Journal. 27 (4): 89–94.

- Vardanyan, Ruben; Vardanyan, Karen (December 2008). "Newly-found groups of Artaxiad copper coins" (PDF). Armenian Numismatic Journal. II. 4 (4): 77–95.

- Wiesehöfer, Joseph (1986). "Ardašīr I i. History". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/4: Architecture IV–Armenia and Iran IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 371–376. ISBN 978-0-71009-104-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Litovchenko, Sergey (2003). Римско-армянские отношения в I в. до н. э. ‑ начале I в. н. э. [Roman-Armenian relations from the 1st century BC to the beginning of the 1st century AD] (PDF) (Thesis). University of Kharkiv.

- Russell, J. R. (1986). "Armenia and Iran iii. Armenian Religion". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/4: Architecture IV–Armenia and Iran IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 438–444. ISBN 978-0-71009-104-8.