Arctium lappa

| Arctium lappa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Greater burdock | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Arctium |

| Species: | A. lappa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Arctium lappa | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Synonymy

| |

Arctium lappa, commonly called greater burdock,[2] gobō (牛蒡/ゴボウ),[2] edible burdock,[2] lappa,[2] beggar's buttons,[2] thorny burr, or happy major[3] is a Eurasian species of plants in the family Asteraceae, cultivated in gardens for its root used as a vegetable. It has become an invasive weed of high-nitrogen soils in North America, Australia, and other regions.[4][5][6][7]

Description

[edit]Greater burdock is a biennial plant, rather tall, reaching as much as 3 metres (10 feet).[8] It has large, alternating, wavy-edged cordiform leaves that have a long petiole and are pubescent on the underside.[9][10]

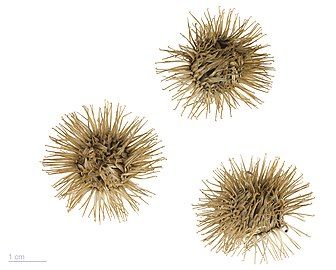

The flowers are purple and grouped in globular capitula, united in clusters. They appear in mid-summer, from July to September.[11] The capitula are surrounded by an involucre made out of many bracts, each curving to form a hook, allowing the mature fruits to be carried long distances on the fur of animals. The fruits are achenes; they are long, compressed, with short pappus hairs. These are a potential hazard for humans, horses, and dogs. The minute, sharply-pointed, bristly pappus hairs easily detach from the top of the achenes and are carried by the slightest breeze – attaching to skin, mucous membranes, and eyes where they can cause severe dermal irritation, possible respiratory manifestations, and ophthalmia.[12] The fleshy taproot can grow up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) deep.[9]

-

Arctium lappa L. (right), illustration from the Japanese agricultural encyclopedia Seikei Zusetsu (1804)

-

A 180 cm (6 ft) tall man holding a leaf

-

Inflorescence

Chemistry

[edit]Burdock roots contain mucilage, sulfurous acetylene compounds, polyacetylenes and bitter guaianolide-type constituents.[citation needed] Seeds contain arctigenin, arctiin, and butyrolactone lignans.[13][14][15]

Similar species

[edit]The burdock could be confused with rhubarb, the leaves of which are toxic.[10]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]This species is native to the temperate regions of the Old World, from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean, and from the British Isles through Russia, and the Middle East to India, China, Taiwan and Japan.

It is naturalized almost everywhere and is usually found in disturbed areas, especially in soil rich in humus and nitrogen, preferring full sunlight.

Ecology

[edit]The leaves of greater burdock provide food for the caterpillars of some Lepidoptera, such as the thistle ermine (Myelois circumvoluta).

Uses

[edit]The species is commonly cultivated in Japan.

Culinary

[edit]| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 302 kJ (72 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

17.34 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 2.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 3.3 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.15 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.53 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[16] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[17] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The roots are edible cooked.[10] Greater burdock root is known as niúbàng (牛蒡) in Chinese, which was borrowed into Japanese as gobō and Korean as ueong (우엉), and is widely eaten in Japan, Korea and Taiwan. It was used in Europe during the Middle Ages as a vegetable, but now it is rarely used except in Italy and Portugal, where it is known as bardana or "garduna". It is also known under the same names and eaten in Brazil. Plants are cultivated for their slender roots, which can grow about 1 m long and 2 centimetres (3⁄4 in) across. The root was traditionally used in Britain as a flavouring in the herbal drink dandelion and burdock, which is still commercially produced.

The root is very crisp and has a sweet, mild, and pungent flavor with a little muddy harshness that can be reduced by soaking julienned/shredded roots in water for five to ten minutes. The harshness shows excellent harmonization with pork in miso soup (tonjiru) and takikomi gohan (a Japanese-style pilaf). A popular Japanese dish is kinpira gobō, julienned or shredded burdock root and carrot, braised with soy sauce, sugar, mirin and/or sake, and sesame oil. Another is burdock makizushi, rolled sushi filled with pickled burdock root; the burdock root is often artificially colored orange to resemble a carrot. Burdock root can also be found as a fried snack food similar in taste and texture to potato chips and is occasionally used as an ingredient in tempura dishes. Fermentation of the root by Aspergillus oryzae is also used for making miso and rice wine in Japanese cuisine.[18]

The tender leaf stalks can be peeled and eaten raw or cooked.[10] Immature flower stalks may also be harvested in late spring, before flowers appear. The taste resembles that of artichoke, a burdock relative.

In the second half of the 20th century, burdock achieved international recognition for its culinary use due to the increasing popularity of the macrobiotic diet, which advocates its consumption. The root contains a fair amount of dietary fiber (GDF, 6 g per 100 g), calcium, potassium, amino acids,[19] and is low calorie. It contains polyphenols that causes darkened surface and muddy harshness by formation of tannin-iron complexes. Those polyphenols are caffeoylquinic acid derivatives.[20]

Traditional medicine

[edit]Dried burdock roots (Bardanae radix) are used in traditional medicine.[21] The seeds of greater burdock are employed in traditional Chinese medicine under the name niubangzi[22] (Chinese: 牛蒡子; pinyin: niúpángzi; some dictionaries list the Chinese as just 牛蒡 niúbàng).

References

[edit]- ^ The Plant List Arctium lappa L.

- ^ a b c d e "Arctium lappa". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ Grieve, Maud (1971). A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses, Volume 1. Courier Corporation. p. 143. ISBN 9780486227986.

- ^ Flora of North America Vol. 19, 20 and 21 Page 169 Great burdock, grande bardane, Arctium lappa Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 816. 1753.

- ^ Atlas of Living Australia, Arctium lappa L.

- ^ Biota of North America Program 2014 county distribution map

- ^ Altervista Flora Italiana, Bardana maggiore Arctium lappa L. many photos

- ^ "COMMON BURDOCK, Arctium minus," Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide, Ohio State University, http://www.oardc.ohio-state.edu/weedguide/singlerecord.asp?id=900

- ^ a b Flora of China Vol. 20-21 Page 153 牛蒡 niu bang Arctium lappa Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 816. 1753.

- ^ a b c d United States Department of the Army (2009). The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-60239-692-0. OCLC 277203364.

- ^ Rose, Francis (1981). The Wild Flower Key. Frederick Warne & Co. pp. 386–387. ISBN 0-7232-2419-6.

- ^ Cole T.C.H.; Su S.; Hilger H.H. (2016). "Arctium lappa – Burdock pappus bristles can cause skin irritation and burdock ophthalmia". PeerJ Preprints. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.1871v1.

- ^ Hayashi, K; Narutaki, K; Nagaoka, Y; Hayashi, T; Uesato, S (2010). "Therapeutic effect of arctiin and arctigenin in immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice infected with influenza". Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 33 (7): 1199–1205. doi:10.1248/bpb.33.1199. PMID 20606313.

- ^ Xie L.-H.; Ahn E.-M.; Akao T.; Abdel-Hafez A.A.-M.; Nakamura N.; Hattori M. (2003). "Transformation of arctiin to estrogenic and antiestrogenic substances by human intestinal bacteria". Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 51 (4): 378–384. doi:10.1248/cpb.51.378. PMID 12672988.

- ^ Matsumoto T.; Hosono-Nishiyama K.; Yamada H. (2006). "Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of from Arctium lappa on leukemic cells". Planta Medica. 72 (3): 276–278. doi:10.1055/s-2005-916174. PMID 16534737. S2CID 41642519.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ "New probiotic identified in fermented Japanese vegetable: Enzyme improves colon health in rats". Science Daily.

- ^ (井関 清経=健康サイト編集). "ゴボウの皮はむかないのが"新常識" (06/01/19) - ニュース - nikkei BPnet". Nikkeibp.co.jp. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ^ Maruta, Yoshihiko; Kawabata, Jun; Niki, Ryoya (1995). "Antioxidative caffeoylquinic acid derivatives in the roots of burdock (Arctium lappa L.)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 43 (10): 2592. doi:10.1021/jf00058a007.

- ^ Chan Y.-S.; Cheng L.-N.; Wu J.-H.; Chan E.; Kwan Y.-W.; Lee S.M.-Y.; Leung G.P.-H.; Yu P.H.-F.; Chan S.-W. (2010). "A review of the pharmacological effects of Arctium lappa (burdock)". Inflammopharmacology. 19 (5): 245–54. doi:10.1007/s10787-010-0062-4. hdl:10397/4042. PMID 20981575. S2CID 15181217.

- ^ School of Chinese Medicine database Archived August 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine