Beekeeping

Beekeeping (or apiculture) is the maintenance of bee colonies, commonly in artificial beehives. Honey bees in the genus Apis are the most commonly kept species but other honey producing bees such as Melipona stingless bees are also kept. Beekeepers (or apiarists) keep bees to collect honey and other products of the hive: beeswax, propolis, bee pollen, and royal jelly. Other sources of beekeeping income include pollination of crops, raising queens, and production of package bees for sale. Bee hives are kept in an apiary or "bee yard".

The keeping of bees by humans, primarily for honey production, began around 10,000 years ago. A sample of 5,500-year-old honey was unearthed from the grave of a noblewoman during an archaeological excavations in 2003 near the town of Borjomi, Georgia.[1] Ceramic jars found in the grave contained several types of honey, including linden and flower honey. Domestication of bees can be seen in Egyptian art[2] from around 4,500 years ago; there is also evidence of beekeeping in ancient China, Greece, and Maya.

In the modern era, beekeeping is often used for crop pollination and the collection of its byproducts, such as wax and propolis. The largest beekeeping operations are agricultural businesses but many small beekeeping operations are run as a hobby. As beekeeping technology has advanced, beekeeping has become more accessible, and urban beekeeping was described as a growing trend as of 2016.[3] Some studies have found city-kept bees are healthier than those in rural settings because there are fewer pesticides and greater biodiversity in cities.[4]

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]At least 10,000 years ago, humans began to attempt to maintain colonies of wild bees in artificial hives made from hollow logs, wooden boxes, pottery vessels, and woven straw baskets known as skeps. Depictions of humans collecting honey from wild bees date to 10,000 years ago.[6] Beekeeping in pottery vessels began about 9,000 years ago in North Africa.[7] Traces of beeswax have been found in potsherds throughout the Middle East beginning about 7,000 BCE.[7] Domestication of bees is shown in Egyptian art from around 4,500 years ago.[8] Simple hives and smoke were used, and honey was stored in jars, some of which were found in the tombs of pharaohs such as Tutankhamun. In the 18th century, European understanding of the colonies and biology of bees allowed the construction of the movable comb hive so honey could be harvested without destroying the entire colony.

Honeybees were kept in Egypt from antiquity.[9] On the walls of the sun temple of Nyuserre Ini from the Fifth Dynasty before 2,422 BCE, workers are depicted blowing smoke into hives as they remove honeycombs.[10] Inscriptions detailing the production of honey are found on the tomb of Pabasa from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty c. 650 BCE, in which cylindrical hives are depicted along with people pouring honey into jars.[11]

An inscription records the introduction of honey bees into the land of Suhum in Mesopotamia, where they were previously unknown:

I am Shamash-resh-ușur, the governor of Suhu and the land of Mari. Bees that collect honey, which none of my ancestors had ever seen or brought into the land of Suhu, I brought down from the mountain of the men of Habha, and made them settle in the orchards of the town 'Gabbari-built-it'. They collect honey and wax, and I know how to melt the honey and wax – and the gardeners know too. Whoever comes in the future, may he ask the old men of the town, (who will say) thus: "They are the buildings of Shamash-resh-ușur, the governor of Suhu, who introduced honey bees into the land of Suhu".

— translated text from Stele, (Dalley, 2002)[12]

The oldest archaeological finds directly relating to beekeeping have been discovered at Rehov, a Bronze and Iron Age archaeological site in the Jordan Valley, Israel.[13] Thirty intact hives made of straw and unbaked clay were discovered in the ruins of the city, dating from about 900 BCE, by archaeologist Amihai Mazar. The hives were found in orderly rows, three high, in a manner that according to Mazar could have accommodated around 100 hives, held more than one million bees and had a potential annual yield of 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) of honey and 70 kilograms (150 lb) of beeswax, and are evidence an advanced honey industry in Tel Rehov, Israel 3,000 years ago.[14][15][16]

In ancient Greece, in Crete and Mycenae, there existed a system of high-status apiculture that is evidenced by the finds of hives, smoking pots, honey extractors and other beekeeping paraphernalia in Knossos. Beekeeping was considered a highly valued industry controlled by beekeeping overseers—owners of gold rings depicting apiculture scenes rather than religious ones as they have been reinterpreted recently, contra Sir Arthur Evans.[17] Aspects of the lives of bees and beekeeping are discussed at length by Aristotle. Beekeeping was also documented by the Roman writers Virgil, Gaius Julius Hyginus, Varro, and Columella.[18]

Beekeeping has been practiced in ancient China since antiquity. In a book written by Fan Li (or Tao Zhu Gong) during the Spring and Autumn period are sections describing beekeeping, stressing the importance of the quality of the wooden box used and its effects on the quality of the honey.[19] The Chinese word for honey mi (Chinese: 蜜; pinyin: Mì), reconstructed Old Chinese pronunciation *mjit) was borrowed from proto-Tocharian *ḿət(ə) (where *ḿ is palatalized; cf. Tocharian B mit), cognate with English mead.[20]

The ancient Maya domesticated a species of stingless bee, which they used for several purposes, including making balché, a mead-like alcoholic drink.[21] By 300 BCE they had achieved the highest levels of stingless beekeeping practices in the world.[22] The use of stingless bees is referred to as meliponiculture, which is named after bees of the tribe Meliponini such as Melipona quadrifasciata in Brazil. This variation of beekeeping still occurs today.[23] For instance, in Australia, the stingless bee Tetragonula carbonaria is kept for the production of honey.[24]

Scientific study of honey bees

[edit]European natural philosophers began to scientifically study bee colonies in the 18th century. Eminent among these scientists were Swammerdam, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, Charles Bonnet and François Huber. Swammerdam and Réaumur were among the first to use a microscope and dissection to understand the internal biology of honey bees. Réaumur was among the first to construct a glass-walled observation hive to better observe activities inside hives. He observed queens laying eggs in open cells but did not know how queens were fertilized; the mating of a queen and drone had not yet been observed and many theories held queens were "self-fertile" while others believed a vapor or "miasma" emanating from the drones fertilized queens without physical contact. Huber was the first to prove by observation and experiment that drones physically inseminate queens outside the confines of the hive, usually a great distance away.[25]

Following Réaumur's design, Huber built improved glass-walled observation hives and sectional hives that could be opened like the leaves of a book. This allowed the inspection of individual wax combs and greatly improved direct observation of hive activity. Although he went blind before he was twenty, Huber employed a secretary named François Burnens to make daily observations, conduct experiment and keep accurate notes for more than twenty years. Huber confirmed a hive consists of one queen, who is the mother of every female worker and male drone in the colony. He was also the first to confirm mating with drones takes place outside hives and that queens are inseminated in successive matings with male drones, which occur high in the air at a great distance from the hive. Together, Huber and Burnens dissected bees under the microscope, and were among the first to describe the ovaries and spermatheca (sperm store) of queens, as well as the penis of male drones. Huber is regarded as "the father of modern bee-science" and his work Nouvelles Observations sur Les Abeilles (New Observations on Bees)[26] revealed all of the basic scientific facts of the biology and ecology of honeybees.[25]

Hive designs

[edit]Before the invention of the movable comb hive, the harvesting of honey frequently resulted in the destruction of the whole colony. The wild hive was broken into using smoke to quieten the bees. The honeycombs were pulled out and either immediately eaten whole or crushed, along with the eggs, larvae, and honey they held. A sieve or basket was used to separate the liquid honey from the demolished brood nest. In medieval times in northern Europe, although skeps and other containers were made to house bees, the honey and wax were still extracted after the bee colony was killed.[27] This was usually accomplished by using burning sulfur to suffocate the colony without harming the honey within. It was impossible to replace old, dark-brown brood comb in which larval bees are constricted by layers of shed pupal skins.[28]

The movable frames of modern hives are considered to have been developed from the traditional basket top bar (movable comb) hives of Greece, which allowed the beekeeper to avoid killing the bees.[29] The oldest evidence of their use dates to 1669, although it is probable their use is more than 3,000 years old.[30]

Intermediate stages in the transition from older methods of beekeeping were recorded in 1768 by Thomas Wildman, who described advances over the destructive, skep-based method so bees no longer had to be killed to harvest their honey.[31] Wildman fixed an array of parallel wooden bars across the top of a straw hive 10 inches (25 cm) in diameter "so that there are in all seven bars of deal to which the bees fix their combs", foreshadowing future uses of movable-comb hives. He also described using such hives in a multi-story configuration, foreshadowing the modern use of supers: he added successive straw hives below and later removed the ones above when free of brood and filled with honey so the bees could be separately preserved at the harvest the following season. Wildman also described the use of hives with "sliding frames" in which the bees would build their comb.[32]

Wildman's book acknowledges the advances in knowledge of bees made by Swammerdam, Maraldi, and de Réaumur—he includes a lengthy translation of Réaumur's account of the natural history of bees. Wildman also describes the initiatives of others in designing hives for the preservation of bees when taking the harvest, citing reports from Brittany in the 1750s due to the Comte de la Bourdonnaye. Another hive design was invented by Rev. John Thorley in 1744; the hive was placed in a bell jar that was screwed onto a wicker basket. The bees were free to move from the basket to the jar, and honey was produced and stored in the jar. The hive was designed to keep the bees from swarming as much as they would have in other hive designs.[33]

In the 19th century, changes in beekeeping practice were completed through the development of the movable comb hive by the American Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth, who was the first person to make practical use of Huber's earlier discovery of a specific spatial distance between the wax combs, later called the bee space, which bees do not block with wax but keep as a free passage. Having determined this bee space, which is commonly given as between 6 and 9 mm (0.24 and 0.35 in),[34][35] though up to 15 mm (0.59 in) has been found in populations in Ethiopia.[36] Langstroth then designed a series of wooden frames within a rectangular hive box, carefully maintaining the correct space between successive frames. He found the bees would build parallel honeycombs in the box without bonding them to each other or to the hive walls. This enables the beekeeper to slide any frame out of the hive for inspection without harming the bees or the comb; and protecting the eggs, larvae and pupae in the cells. It also meant combs containing honey could be gently removed and the honey extracted without destroying the comb. The emptied honeycombs could then be returned intact to the bees for refilling. Langstroth's book The Hive and Honey-bee (1853), describes his rediscovery of the bee space and the development of his patent movable comb hive. The invention and development of the movable comb hive enabled the growth of large-scale, commercial honey production in both Europe and the U.S.

20th and 21st century hive designs

[edit]Langstroth's design of movable comb hives was adopted by apiarists and inventors in both North America and Europe, and a wide range of moveable comb hives were developed in England, France, Germany and the United States.[37] Classic designs evolved in each country; Dadant hives and Langstroth hives are still dominant in the U.S.; in France the De-Layens trough hive became popular, in the UK a British National hive became standard by the 1930s, although in Scotland the smaller Smith hive is still popular. In some Scandinavian countries and in Russia, the traditional trough hive persisted until late in the 20th century and is still kept in some areas. The Langstroth and Dadant designs, however, remain ubiquitous in the U.S. and in many parts of Europe, though Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France and Italy all have their own national hive designs. Regional variations of hive were developed according to climate, floral productivity and reproductive characteristics of the subspecies of native honey bees in each bio-region.[37]

The differences in hive dimensions are insignificant in comparison to the common factors in these hives: they are all square or rectangular; they all use movable wooden frames; and they all consist of a floor, brood-box, honey super, crown-board and roof. Hives have traditionally been constructed from cedar, pine or cypress wood but in recent years, hives made from injection-molded, dense polystyrene have become increasingly common.[38] Hives also use queen excluders between the brood-box and honey supers to keep the queen from laying eggs in cells next to those containing honey intended for consumption. With the 20th-century advent of mite pests, hive floors are often replaced, either temporarily or permanently, with a wire mesh and a removable tray.[38]

In 2015, the Flow Hive system was invented in Australia by Cedar Anderson and his father Stuart Anderson,[39] whose design allows honey to be extracted without cumbersome centrifuge equipment.

Pioneers of practical and commercial beekeeping

[edit]In the 19th century, improvements were made in the design and production of beehives, systems of management and husbandry, stock improvement by selective breeding, honey extraction and marketing. Notable innovators of modern beekeeping include:

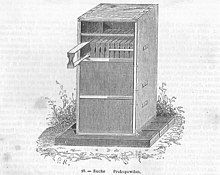

Petro Prokopovych used frames with channels in the side of the woodwork; these were packed side-by-side in stacked boxes. Bees traveled between frames and boxes via these channels,[40] which were similar to the cutouts in the sides of modern wooden sections.[41]

Jan Dzierżon' beehive design has influenced modern beehives.[42]

François Huber made significant discoveries about the bee life cycle and communication between bees. Despite being blind, Huber discovered a large amount of information about the queen bee's mating habits and her contact with the rest of the hive. His work was published as New Observations on the Natural History of Bees.[43]

L. L. Langstroth has influenced modern beekeeping practice more than anyone else. His book The Hive and Honey-bee was published in 1853.[44]

Moses Quinby, author of Mysteries of Bee-Keeping Explained, invented the bee smoker in 1873.[45][46]

Amos Root, author of the A B C of Bee Culture, which has been continuously revised and remains in print, pioneered the manufacture of hives and the distribution of bee packages in the United States.[citation needed]

A. J. Cook author of The Bee-Keepers' Guide; or Manual of the Apiary, 1876.[47]

Dr. C.C. Miller was one of the first entrepreneurs to make a living from apiculture. By 1878, he made beekeeping his sole business activity. His book, Fifty Years Among the Bees, remains a classic and his influence on bee management persists into the 21st century.[48]

Franz Hruschka was an Austrian/Italian military officer who in 1865 invented a simple machine for extracting honey from the comb by means of centrifugal force. His original idea was to support combs in a metal framework and then spin them within a container to collect honey that was thrown out by centrifugal force. This meant honeycombs could be returned to a hive empty and undamaged, saving the bees a vast amount of work, time and materials. This invention significantly improved the efficiency of honey harvesting and catalyzed the modern honey industry.[49]

Walter T. Kelley was an American pioneer of modern beekeeping in the early-and mid-20th century. He greatly improved upon beekeeping equipment and clothing, and went on to manufacture these items and other equipment. His company sold products worldwide and his book How to Keep Bees & Sell Honey, encouraged a boom in beekeeping following World War II.[50]

Cary W. Hartman (1859–1947), lecturer, well known beekeeping enthusiast and honey promoter was elected President of the California State Beekeepers' Association in 1921.[51][52]

In the UK, practical beekeeping was led in the early 20th century by a few men, pre-eminently Brother Adam and his Buckfast bee, and R.O.B. Manley, author of books including Honey Production in the British Isles and inventor of the Manley frame, which is still universally popular in the UK. Other notable British pioneers include William Herrod-Hempsall and Gale.[53][54]

Ahmed Zaky Abushady (1892–1955) was an Egyptian poet, medical doctor, bacteriologist, and bee scientist, who was active in England and Egypt in the early twentieth century. In 1919, Abushady patented a removable, standardized aluminum honeycomb. In the same year, he founded The Apis Club in Benson, Oxfordshire, which later became the International Bee Research Association (IBRA). In Egypt in the 1930s, Abushady established The Bee Kingdom League and its organ The Bee Kingdom.[55]

Hives and other equipment

[edit]Horizontal hives

[edit]

A Horizontal top-bar hive is a single-story, frameless beehive in which the comb hangs from removable bars that form a continuous roof over the comb, whereas the frames in most current hives allow space for bees to move between boxes. Hives that have frames or that use honey chambers in summer and use management principles similar to those of regular top-bar hives are sometimes also referred to as top-bar hives. Top-bar hives are rectangular and are typically more than twice as wide as multi-story framed hives commonly found in English-speaking countries. Top-bar hives usually include one box and allow for beekeeping methods that interfere very little with the colony. While conventional advice often recommends inspecting each colony each week during the warmer months,[56] some beekeepers fully inspect top-bar hives only once a year,[57] and only one comb needs to be lifted at a time.[58]

Vertical stackable hives

[edit]There are three types of vertical stackable hives: hanging or top-access frame, sliding or side-access frame, and top bar.

Hanging-frame hive designs include Langstroth, the British National, Dadant, Layens, and Rose, which differ in size and number of frames. The Langstroth was the first successful top-opened hive with movable frames. Many other hive designs are based on the principle of bee space that was first described by Langstroth, and is a descendant of Jan Dzierzon's Polish hive designs. Langstroth hives are the most-common size in the United States and much of the world; the British National is the most common size in the United Kingdom; Dadant and Modified Dadant hives are widely used in France and Italy, and Layens by some beekeepers, where their large size is an advantage. Square Dadant hives–often called 12-frame Dadant or Brother Adam hives–are used in large parts of Germany and other parts of Europe by commercial beekeepers.

Any hanging-frame hive design can be built as a sliding frame design. The AZ Hive, the original sliding frame design, integrates hives using Langstroth-sized frames into a honey house to streamline the workflow of honey harvest by localization of labor, similar to cellular manufacturing. The honey house can be a portable trailer, allowing the beekeeper to move hives to a site and provide pollination services.

Top-bar stackable hives use top bars instead of full frames. The most common type is the Warre hive, although any hive with hanging frames can be converted into a top-bar stackable hive by using only the top bar rather than the whole frame. This may work less well with larger frames, where crosscomb and attachment can occur more readily.

Protective clothing

[edit]

Most beekeepers wear some protective clothing. Novice beekeepers usually wear gloves and a hooded suit or hat and veil. Experienced beekeepers sometimes choose not to use gloves because they inhibit delicate manipulations. The face and neck are the most important areas to protect, so most beekeepers wear at least a veil.[59] Defensive bees are attracted to the breath; a sting on the face can lead to much more pain and swelling than a sting elsewhere, while a sting on a bare hand can usually be quickly removed by fingernail scrape to reduce the amount of venom injected.

Traditionally, beekeeping clothing is pale-colored because of the natural color of cotton and the cost of coloring is an expense not warranted for workwear, though some consider this to provide better differentiation from the colony's natural predators such as bears and skunks, which tend to be dark-colored. It is now known bees see in ultraviolet wavelengths and are also attracted to scent. The type of fabric conditioner used has more impact than the color of the fabric.[60][61]

Stings that are retained in clothing fabric continue to pump out an alarm pheromone that attracts aggressive action and further stinging attacks. Attraction can be minimized with regular washing.[citation needed]

Smoker

[edit]

Most beekeepers use a smoker, a device that generates smoke from the incomplete combustion of fuels. Although the exact mechanism is disputed, it is said smoke calms bees. Some claim it initiates a feeding response in anticipation of possible hive abandonment due to fire.[62] It is also thought smoke masks alarm pheromones released by guard bees or bees that are squashed in an inspection. The ensuing confusion creates an opportunity for the beekeeper to open the hive and work without triggering a defensive reaction.

Many types of fuel can be used in a smoker as long as it is natural and not contaminated with harmful substances. Common fuels include hessian, twine, pine needles, corrugated cardboard, and rotten or punky wood. Indian beekeepers, especially in Kerala, often use coconut fibers, which are readily available, safe, and cheap. Some beekeeping supply sources also sell commercial fuels like pulped paper, compressed cotton and aerosol cans of smoke. Other beekeepers use sumac as fuel because it ejects much smoke and lacks an odor.

Some beekeepers use "liquid smoke" as a safer, more convenient alternative. It is a water-based solution that is sprayed onto the bees from a plastic spray bottle. A spray of clean water can also be used to encourage bees to move on.[63] Torpor may also be induced by the introduction of chilled air into the hive, while chilled carbon dioxide may have harmful, long-term effects.[64]

Few anecdotal stories of using the smoke from burning fungi in England or Europe for centuries have been published. Several more recent studies describe anaesthesia of honeybees use of smoke from burning fungi.[65][66] The fungi reported to have been used to smoke bees are the puffballs Lycoperdon gigantium, L. wahlbergii and the conks, Fomes fomentarius and F. igiarius. When fungi are burned, the characteristic smell is due to the pyrolysis of the keratin cell wall of fungi. Besides being a major fungi constituent, keratin is found in animal tissues, such as hair or feathers. Anaesthesia experiments done using smoke from pyrolysis of L. wahlbergii, human hair and chicken feathers showed no difference in long-term mortality of anesthetized honeybees and non-treated bees in the same hive. Hydrogen sulphide was identified as the major combustion product that is responsible for putting the bees to sleep. Note – hydrogen sulphide is toxic to humans at high concentrations.[67]

Hive tool

[edit]

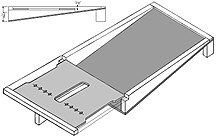

Most beekeepers use a hive tool when working on their hives. The two main types are the American hive tool; and the Australian hive tool often called a 'frame lifter'. They are used to scrape off burr-comb from around the hive, especially on top of the frames. They are also used to separate the frames before lifting out of the hive.

Safety and husbandry

[edit]Stings

[edit]Some beekeepers believe pain and irritation from stings decreases if a beekeeper receives more stings, and they consider it important for safety of the beekeeper to be stung a few times a season. Beekeepers have high levels of antibodies, mainly Immunoglobulin G, caused by a reaction to the major antigen of bee venom, phospholipase A2 (PLA).[68] Antibodies correlate with the frequency of bee stings.

The entry of venom into the body from bee stings may be hindered and reduced by protective clothing that allows the wearer to remove stings and venom sacs with a simple tug on the clothing. Although the stinger is barbed, a worker bee's stinger is less likely to become lodged into clothing than human skin.

Symptoms of being stung include redness, swelling and itching around the site of the sting. In mild cases, pain and swelling subside in two hours. In moderate cases, the red welt at the sting site will become slightly larger for one or two days before beginning to heal. A severe reaction, which is rare among beekeepers, results in anaphylactic shock.[69]

If a beekeeper is stung by a bee, the sting should be removed without squeezing the attached venom glands. A quick scrape with a fingernail is effective and intuitive, and ensures the venom injected does not spread so the side effects of the sting will go away sooner. Washing the affected area with soap and water can also stop the spread of venom. Ice or a cold compress can be applied to the sting area.[69]

Internal temperature of a hive

[edit]

Bees maintain the internal temperature of their hive at about 35 °C (95 °F).[70] Their ability to do this is known as social homeostasis and was first described by Gates in 1914.[71] During hot weather, bees cool the hive by circulating cool air from the entrance through the hive and out again;[72] and if necessary by placing water, which they fetch, throughout the hive to create evaporative cooling.[73] In cold weather, packing and insulation of the bee hive is believed to be beneficial.[74] The extra insulation is believed to reduce the amount of honey the bees consume and makes it easier for them to maintain the hive's temperature. The desire for insulation encouraged the use of double-walled hives with an outer wall of timber or polystyrene; and hives constructed from a ceramic.[75]

Location of hives

[edit]There has been considerable debate about the best location for hives. Virgil thought they should be located near clear springs, ponds or shallow brooks. Wildman thought they should face to the south or west. All writers agree hives should be sheltered from strong winds. In hot climates, hives are often placed under the shade of trees in summer.[76] Researchers in the U.S. found domestic honey bees placed in national parks compete with native bee species for resources. A further review of the literature concluded large concentrations of beehives on continents where they are not native, such as North and South America, could compete against the native bees; this, however, was not as strongly observed in areas where domestic bees are native such as Europe and Africa, where the different bee species have adapted to have a narrower overlapping of forage preferences.[77]

Natural beekeeping

[edit]

The natural beekeeping movement believes bee hives are weakened by modern beekeeping and agricultural practices, such as crop spraying, hive movement, frequent hive inspections, artificial insemination of queens, routine medication, and sugar water feeding.[78] Practitioners of "natural beekeeping" tend to use variations of the top-bar hive, which is a simple design that retains the concept of having a movable comb without the use of frames or a foundation. The horizontal top-bar hive, as promoted by many writers, can be seen as a modernization of hollow log hives, with the addition of wooden bars of specific width from which bees hang their combs. The widespread adoption of Natural Beekeeping methods in recent years can be attributed to the 2007 publications of Natural Beekeeping [79] by Ross Conrad, and The Barefoot Beekeeper[80] by Philip Chandler, which challenges many aspects of modern beekeeping and offers the horizontal top-bar hive as a viable alternative to the ubiquitous Langstroth-style movable-frame hive.

A vertical top-bar hive is the Warré hive, based on a design by the French priest Abbé Émile Warré (1867–1951) and popularized by David Heaf in his English translation of Warré's book L'Apiculture pour Tous as Beekeeping For All.[81]

Urban and backyard beekeeping

[edit]

Related to natural beekeeping, urban beekeeping is an attempt to revert to a less-industrialized way of obtaining honey by using small-scale colonies that pollinate urban gardens. Some have found city bees are healthier than rural bees because there are fewer pesticides and greater biodiversity in urban gardens.[82] Urban bees may fail to find forage, however, and homeowners can use their land to help feed local bee populations by planting flowers that provide nectar and pollen. An environment of year-round, uninterrupted bloom creates an ideal environment for colony reproduction.[83]

Using managed honeybee colonies to fill the ecological niche of pollinators in urban environments is also thought to be crucial to preventing the formation of feral colonies by more destructive species like the Africanized honeybee (AHB).[84]

Indoor beekeeping

[edit]Modern beekeepers have experimented with raising bees indoors in a controlled environment or in indoor observation hives. This may be done for reasons of space and monitoring, or in the cooler months, when large commercial beekeepers may move colonies to "wintering" warehouses with fixed temperature, light, and humidity. This helps bees remain healthy but relatively dormant. These relatively dormant "wintered" bees survive on stored honey, and new bees are not born.[85]

Experiments in raising bees indoors for longer durations have looked into more precise and varying environment controls. In 2015, MIT's "Synthetic Apiary" project simulated springtime inside a closed environment for several hives throughout the winter. They provided food sources and simulated long days, and saw activity and reproduction levels comparable to the levels seen outdoors in warm weather. They concluded such an indoor apiary could be sustained year-round if needed.[86][87]

Behavior of honey bees

[edit]Colony reproduction

[edit]

Honey bee colonies are dependent on their queen, who is the only egg-layer. Although queens have a three-to-four-year adult lifespan, diminished longevity of queens—less than a year—is commonly and increasingly observed.[88] The queen can choose whether to fertilize an egg as she lays it; fertilized eggs develop into a female worker bees and unfertilized eggs become male drones. The queen's choice of egg type depends on the size of the open brood cell she encounters on the comb. In a small worker cell, she lays a fertilized egg; she lays unfertilized drone eggs in larger drone cells.[89]

When the queen is fertile and laying eggs, she produces a variety of pheromones that control the behavior of the bees in the hive; these are commonly called queen substance. Each pheromone has a different function. As the queen ages, she begins to run out of stored sperm and her pheromones begin to fail.[90]

As the queen's pheromones fail, the bees replace her by creating a new queen from one of her worker eggs. They may do this because she has been physically injured, because she has run out of sperm and cannot lay fertilized eggs, and has become a drone-laying queen, or because her pheromones have dwindled to the point at which they cannot control all of the bees in the hive. At this juncture, the bees produce one or more queen cells by modifying existing worker cells that contain a normal female egg. They then either supersede the queen without swarming or divide the hive into two colonies through swarm-cell production, which leads to swarming.[91]

Supersedure is a valued behavioral trait because hive that supersedes its old queen does not lose any stock; rather it creates a new queen and the old one either naturally dies or is killed when the new queen emerges. In these hives, bees produce only one or two queen cells, most often in the center of the face of a broodcomb.[92] Swarm-cell production involves the creation of twelve or more queen cells. These are large, peanut-shaped protrusions requiring space, for which reason they are often located around the edges—commonly at the sides and the bottom—of the broodcomb.[92]

Once either process has begun, the old queen leaves the hive when the first queen cells hatch, and is accompanied by a large number of bees—predominantly young bees called wax-secretors—which form the basis of the new hive. Scouts are sent from the swarm to find suitable hollow trees or rock crevices; when one is found, the entire swarm moves in. Within hours, the new colony's bees build new wax brood combs using honey stores with which the young bees have filled themselves before leaving the old hive. Only young bees can secrete wax from special abdominal segments, which is why swarms tend to contain more young bees. Often a number of virgin queens accompany the first swarm, known as the "prime swarm", and the old queen is replaced as soon as a daughter queen mates and begins laying. Otherwise, she is quickly superseded in the new hive.[92]

Different sub-species of Apis mellifera exhibit differing swarming characteristics. In North America, northern black races are thought to swarm less and supersede more whereas the southern yellow-and-gray varieties are said to swarm more frequently. Swarming behavior is complicated because of the prevalence of cross-breeding and hybridization of the sub-species.[92] Italian bees are very prolific and inclined to swarm; Northern European black bees have a strong tendency to supersede their old queen without swarming. These differences are the result of differing evolutionary pressures in the regions in which each sub-species evolved.[92]

Factors that trigger swarming

[edit]According to George S. Demuth, the main factors that increase the swarming tendency of bees are:[93]

- The genetics of bees; the strength of the swarming instinct

- Congestion of the brood nest

- Insufficient empty combs for ripening nectar and storing honey

- Inadequate ventilation

- Having an old queen

- Warming weather conditions.

Demuth attributed some of his comments to Snelgrove.[94]

Some beekeepers carefully monitor their colonies in spring for the appearance of queen cells, which are a dramatic signal the colony is determined to swarm.[92] After leaving the old hive, the swarm looks for shelter. A beekeeper may capture it and introduce it into a new hive. Otherwise, the swarm reverts to a feral state and finds shelter in a hollow tree or other suitable habitat.[92] A small after-swarm has less chance of survival and may threaten the original hive's survival if the number of remaining bees is unsustainable. When a hive swarms despite the beekeeper's preventative efforts, the beekeeper may give the reduced hive two frames of open brood with eggs. This helps replenish the hive more quickly and gives a second opportunity to raise a queen if there is a mating failure.[92]

Artificial swarming

[edit]When a colony accidentally loses its queen, it is said to be queenless.[95] The workers realize the queen is absent after around an hour as her pheromones in the hive fade. Instinctively, the workers select cells containing eggs aged less than three days and dramatically enlarge the cells to form "emergency queen cells". These appear similar to large, one-inch (2.5 cm)-long, peanut-like structures that hang from the center or side of the brood combs. The developing larva in a queen cell is fed differently than an ordinary worker bee; in addition to honey and pollen, she receives a great deal of royal jelly, a special food secreted from the hypopharyngeal gland of young nurse bees.[96] Royal jelly dramatically alters the growth and development of the larva so after metamorphosis and pupation, it emerges from the cell as a queen bee. The queen is the only bee in a colony that has fully developed ovaries; she secretes a pheromone that suppresses the normal development of ovaries in all of her workers.[97]

Beekeepers use the ability of the bees to produce new queens to increase their colonies in a procedure called splitting a colony.[98] To do this, they remove several brood combs from a healthy hive, leaving the old queen behind. These combs must contain eggs or larvae less than three days old and be covered by young nurse bees, which care for the brood and keep it warm. These brood combs and nurse bees are then placed into a small "nucleus hive" with other combs containing honey and pollen. As soon as the nurse bees find themselves in this new hive, and realize they have no queen and begin constructing emergency queen cells using the eggs and larvae in the combs.[92]

Pests and diseases

[edit]Diseases

[edit]The common agents of disease that affect adult honey bees include fungi, bacteria, protozoa, viruses, parasites and poisons. The gross symptoms displayed by affected adult bees are very similar, whatever the cause, making it difficult to ascertain the causes without microscopic identification of microorganisms or chemical analysis of poisons.[99] Since 2006, colony losses from colony collapse disorder (CCD) have been increasing across the world, although the causes of the syndrome are unknown.[100][101] In the U.S., commercial beekeepers have been increasing the number of hives to deal with higher rates of attrition.[102]

Parasites

[edit]Nosema apis is a microsporidian that causes nosemosis, also called nosema, the most-common and widespread disease of the adult honey bee.[103]

Galleria mellonella and Achroia grisella wax moth larvae hatch, tunnel through and destroy comb that contains bee larvae and their honey stores. The tunnels they create are lined with silk, which entangles and starves emerging bees. Destruction of honeycombs also results in leakage and wasting of honey. A healthy hive can manage wax moths but weak colonies, unoccupied hives and stored frames can be decimated.[104]

Small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) is native to Africa but has now spread to most continents. It is a serious pest among honey bees unadapted to it.[105]

Varroa destructor, the Varroa mite, is an established pest of two species of honey bee through many parts of the world and is blamed by many researchers as a leading cause of CCD.[106]

Tropilaelaps mites, of which there are four species, are native to Apis dorsata, Apis laboriosa, and Apis breviligula, but spread to Apis mellifera after they were introduced to Asia.[107]

Acarapis woodi, the tracheal mite, infests the trachea of honey bees.[108]

Predators

[edit]Most predators prefer not to eat honeybees due to their unpleasant sting. Common honeybee predators include large animals such as skunks and bears, which seek the hive's honey and brood, as well as adult bees.[109] Some birds will also eat bees, (for example, bee-eaters, as do some robber flies, such as Mallophora ruficauda, which is a pest of apiculture in South America due to its habit of eating workers while they are foraging in meadows.[110]

Decreasing lifespan

[edit]A 2022 study by researchers at University of Maryland, College Park observed lifespan of caged worker bees is half as long as that observed 50 years ago, and hypothesized decreased worker-bee lifespans should correlate to decreased honey production.[111]

World apiculture

[edit]According to Food and Agriculture Organization data,[112] the world's beehive stock rose from around 50 million in 1961 to around 83 million in 2014, which represents an annual average growth of 1.3%. Average annual growth has accelerated to 1.9% since 2009.

| Country | Production (1000 metric tons) | Consumption (1000 metric tons) | Number of beekeepers | Number of bee hives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe and Russia | ||||

| *69.94 | 52 | |||

| 63.53 | 54 | |||

| 37.00 | 40 | |||

| 21.23 | 89 | 90,000* | 1,000,000* | |

| 19.71 | 4 | |||

| 19.20 | 10 | |||

| 16.27 | 16 | |||

| 15.45 | 30 | |||

| 11.22 | 2 | |||

| 3 to 5 | 6.3 | 30,000 | 430,000 | |

| 2.5 | 5 | *4,000 | *150,000 | |

| North America | ||||

| ***71.18 | 158.75* | 12,029** (210,000 bee keepers) | ***2,812,000 | |

| 45 (2006); 28 (2007)[113] 80.35(2019) | 29 | 13,000 | 500,000 | |

| Latin America | ||||

| 93.42 (Average 84)[114] | 3 | *2984290 | ||

| *61.99 | 31 | *2157870 | ||

| 33.75 | 2 | |||

| 11.87 | 1 | |||

| Oceania | ||||

| 18.46 | 16 | 12,000 | 520,000[115] | |

| 9.69 | 8 | 2602 | 313,399 | |

| Asia | ||||

| *444.1 | 238 | 7,200,000[114] | ||

| *109.33 | 66 | 4,500,000[114][116] | ||

| *75.46 | 3,500,000[114] | |||

| 52.23 | 45 | 9,800,000[114] | ||

| 23.82 | 27 | |||

| 13.59 | 0 | |||

| 10.46 | 10 | |||

| Africa | ||||

| 41.23 | 40 | 4,400,000 | ||

| 28.68 | 28 | |||

| 23.77 | 23 | |||

| 22.00 | 21 | |||

| 16* | 200,000* | 2,000,000* | ||

| 14.23 | 14 | |||

| 4.5 | 27,000 | 400,000 | ||

| ≈2.5*[117] | ≈1.5*[117] | ≈1,790*[117] | ≈92,000*[117] | |

| Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations[118] 2019 data[119][120] | ||||

Gallery: Harvesting honey

[edit]-

Smoking the hive

-

Beekeepers removing a frame

-

Uncapping the cells with an uncapping fork

-

Filtering the honey

-

Bee farming at Home

-

Wooden hives and farmer with packed honey.

See also

[edit]- Africanized bee

- Bee (mythology)

- Bee removal

- Biosecurity

- Castoreum, a product used by medieval beekeepers to increase honey production

- Insects in ethics

- Insect cognition

- List of crop plants pollinated by bees

- More Than Honey – a 2012 Swiss documentary film on honey bees and beekeeping

- Tetragonula carbonaria – a bee kept for honey that is not related to the Honey bee

- Western honey bee life cycle

References

[edit]- ^ "What's the Oldest Honey Ever Found?". 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Tears of Re: Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt". www.apicultural.co.uk. 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "Why urban beekeeping is a rising trend in major cities". PBS NewsHour. 2016-09-04. Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ^ Tanguy, Marion (23 June 2010). "Can cities save our bees? – Marion Tanguy". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Traynor, Kirsten. "Ancient Cave Painting Man of Bicorp". MD Bee. Archived from the original on 2019-10-20. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Dams, M.; Dams, L. (21 July 1977). "Spanish Rock Art Depicting Honey Gathering During the Mesolithic". Nature. 268 (5617): 228–230. Bibcode:1977Natur.268..228D. doi:10.1038/268228a0. S2CID 4177275.

- ^ a b Roffet-Salque, Mélanie; et al. (14 June 2016). "Widespread exploitation of the honeybee by early Neolithic farmers". Nature. 534 (7607): 226–227. doi:10.1038/nature18451. hdl:10379/13692. PMID 26560301.

- ^ Crane, Eva (1999). The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting. London: Duckworth. ISBN 9780715628270.

- ^ "Ancient Egypt: Bee-keeping". Reshafim.org.il. 2003-04-06. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ Bodenheimer, F. S. (1960). Animal and Man in Bible Lands. Brill Archive. p. 79.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Dalley, S. (2002). Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities (2 ed.). Gorgias Press LLC. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-931956-02-4.

- ^ "Oldest known archaeological example of beekeeping discovered in Israel". Thaindian.com. 2008-09-01. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ Mazar, Amihai and Panitz-Cohen, Nava, (December 2007) It Is the Land of Honey: Beekeeping at Tel Rehov Near Eastern Archaeology, Volume 70, Number 4, ISSN 1094-2076

- ^ Friedman, Matti (September 4, 2007), "Israeli archaeologists find 3,000-year-old beehives" Archived 2022-01-19 at the Wayback Machine in USA Today, Retrieved 2010-01-04

- ^ Crane, Eva The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting, Routledge 1999, ISBN 978-0-415-92467-2, 720 pp.

- ^ Haralampos V. Harissis; Anastasios V. Harissis (2009). Apiculture in the Prehistoric Aegean. Minoan and Mycenaean Symbols Revisited. Oxford, England: British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 9781407304540. Archived from the original on 2022-01-19. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ Islam, M. R.; Islam, Jaan S.; Zatzman, Gary M.; Rahman, M. Safiur; Mughal, M. A. H. (2015-12-03). The Greening of Pharmaceutical Engineering, Practice, Analysis, and Methodology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-18421-8.

- ^ Chantawannakul, Panuwan; Williams, Geoffrey; Neumann, Peter (2018). Asian Beekeeping in the 21st Century. Springer. ISBN 978-981-10-8222-1.

- ^ Meier, Kristin; Peyrot, Michaël (2017). "The Word for "Honey" in Chinese, Tocharian and Sino-Vietnamese". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 167 (1): 7–22. doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.167.1.0007. ISSN 0341-0137. JSTOR 10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.167.1.0007.

- ^ Kent, Robert B. (1984). "Mesoamerican Stingless Beekeeping". Journal of Cultural Geography. 4 (2): 14–28. doi:10.1080/08873638409478571. ISSN 0887-3631. Archived from the original on 2022-01-19. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Crane, E. (1998). Amerindian honey hunting and hive beekeeping. Acta Americana, 6(1), 5–18

- ^ Quezada-Euán, José Javier G.; May-Itzá, William de Jesús; González-Acereto, Jorge A. (2001-01-01). "Meliponiculture in Mexico: problems and perspective for development". Bee World. 82 (4): 160–167. doi:10.1080/0005772X.2001.11099523. ISSN 0005-772X. S2CID 85263563.

- ^ Halcroft, Megan T.; et al. (2013). "The Australian Stingless Bee Industry: A Follow-up Survey, One Decade on". Journal of Apicultural Research. 52 (2): 1–7. doi:10.3896/ibra.1.52.2.01. S2CID 86326633.

- ^ a b Reuber, Brant (2015). 21st Century Homestead: Beekeeping. Lulu.com. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-312-93733-8.

- ^ François Huber (1814). Nouvelles observations sur les abeilles. Chez J. J. Paschoud, ... et a Geneve. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Wolf, C. W. (2021). Apis Mellifica – Or, The Poison Of The Honey-Bee. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-5287-6221-2.

- ^ van Veen, J. W. (2014). Gupta, Rakesh K.; Reybroeck, Wim; van Veen, Johan W.; Gupta, Anuradha (eds.). Beekeeping for Poverty Alleviation and Livelihood Security. Vol. 1 Ch 12. London: Springer. pp. 350–1. ISBN 978-94-017-9199-1.

- ^ Crane, Eva. The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting. pp. 395–396, 414.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Harissis (Χαρίσης), Haralampos (Χαράλαμπος); Mavrofridis, Georgios (2012). "A 17th Century Testimony On The Use Of Ceramic Top-bar Hives. 2012 | Haralampos (Χαράλαμπος) Harissis (Χαρίσης) and Georgios Mavrofridis". Bee World. 89 (3): 56–58. doi:10.1080/0005772X.2012.11417481. S2CID 85120138. Archived from the original on 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ Thomas Wildman, A Treatise on the Management of Bees London, 1768. https://books.google.com/books?id=CCZAAAAAcAAJ Chapter V. Of the Methods practised for taking the Wax and Honey, without destroying the Bees. pp 93–109 accessed 17 March 2022.

- ^ Thomas Wildman, A Treatise on the Management of Bees London, 1768. https://books.google.com/books?id=CCZAAAAAcAAJ accessed 17 March 2022. Chapter II Of the Management of Bees in Hives and Boxes. pp 79–86.

- ^ Kritsky, Gene (2010). The Quest for the Perfect Hive: A History of Innovation in Bee Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Nelson, Eric V. (August 1967). Agriculture Handbook No. 335. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture. pp. 2, 27. Archived from the original on 2022-04-05. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ Dave Cushman http://www.dave-cushman.net/bee/bsp.html

- ^ Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare. Determination of Bee Space and Cell Dimensions for Jimma Zone Honeybee Eco-Races (Apis malifera), Southwest Ethiopian. Abera Hailu, Kassa Biratu. Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). Jimma Research Center P.O. Box 192 Jimma Ethiopia. ISSN 2224-3208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X (Online) Vol. 6 no. 9 2016. https://www.academia.edu/26826420/Determination_of_Bee_Space_and_Cell_Dimensions_for_Jimma_Zone_Honeybee_Eco_Races_Apis_malifera_Southwest_Ethiopian accessed 20 March 2022

- ^ a b Reuber, Brant (2015). 21st Century Homestead: Beekeeping. Lulu.com. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-312-93733-8.

- ^ a b Reuber, Brant (2015). 21st Century Homestead: Beekeeping. Lulu.com. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-312-93733-8.

- ^ Hassall, Craig (12 September 2017). "Flow Hive: Cedar and Stuart Anderson talk about life one year after crowdfunding success". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. ABC Online. Archived from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- ^ "2 Hryvni, Ukraine". en.numista.com.

- ^ Dave Cushman. "History of British Standards in Beekeeping". dave-cushman.net. Archived from the original on 2013-04-05. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ^ Cincinnati Historical Society; Cincinnati Museum Center; Filson Historical Society (2005). Ohio Valley history. The journal of the Cincinnati Historical Society. Vol. 5–6. Cincinnati Museum Center. p. 96.

- ^ Koutchoumoff, Lisbeth (November 16, 2018). "L'étonnante Histoire du Genevois François Huber, apiculteur aveugle et visionnaire". Le Temps.

- ^ Root, Amos Ives (1891). The ABC of Bee Culture: A Cyclopaedia of Everything Pertaining to the Care of the Honey-bee ...

- ^ Bee Culture. Moses Quinby – http://www.beeculture.com/moses-quinby/ Archived 2018-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thermal Beekeeping: Look Inside a Burning Bee Smoker – https://americanbeejournal.com/thermal-beekeeping-look-inside-a-burning-bee-smoker/ Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Crawford, David L. (1916). "Albert John Cook, DSC". Journal of Entomology and Zoology. 8 (4). Pomona College Dept. of Zoology: 169–170.

- ^ "Bees as business: UMass Amherst, Du Bois Library, SCUA". Archived from the original on 2012-10-14. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "Birth of American Bee Culture: A Look at Advertisements in A.J. Cook's The Bee Keepers' Guide". St Andrews Rare Books. 26 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

... a honey extractor. This machine, invented by Major Francesco De Hruschka in 1865, used centrifugal force to dislodge honey from the combs and collected it into a vat. The extractor, combined with Langstroth's movable comb hive, greatly improved the efficiency of honey harvesting.

- ^ Moffett, Joseph O. (1979). Beekeepers and Associates. p. 69.

- ^ "Gleanings in Bee Culture". A. I. Root Company. June 28, 1921 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Honey Producers' Co-Operator" 1921, March–April, Vol.2 No.3

- ^ "Brother Adam – English Page". perso.unamur.be.

- ^ "Movable frame hives". startbeekeeping.net. 5 April 2009. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ Crane, Eva. The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, New York : Routledge, 1999. OCLC 41049690 [page needed]

- ^ Advice for New Beekeepers UK National Bee Unit. 02/03/2020 http://www.nationalbeeunit.com/index.cfm?pageid=209 accessed 6.6.2020

- ^ Fedor Lazutin. Keeping bees with a smile. Principles and practice of natural beekeeping. p 321. New Society Publishers. April 2020.

- ^ Michael Bush. The Practical Beekeeper. p.551. xstarpublishing.com. 2004. ISBN 978-161476-064-1

- ^ Graham, Joe M., ed. (1992). The Hive and the honey bee: a new book on beekeeping which continues the tradition of "Langstroth on the hive and the honeybee" (Rev. ed.). Hamilton, IL: Dadant. ISBN 0-915698-09-9. OCLC 27344331.

- ^ "What Do Bees See? And How Do We Know?". NC State News. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 2020-04-01. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ^ Murphy, Cheryl. "Well, I'll BEE...Bees see UV". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 2020-01-13. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ^ Newton, David Comstock (March 1967). Behavioral Response of Honey Bees (Apis Mellifera L., Hymenoptera: Apidae) to Colony Disturbance by Smoke, Acetic Acid, Isopentyl Acetate, Light, Temperature and Vibration (Ph.D. thesis). Champaign, IL: University of Illinois. p. 3. Document No. 302256408ProQuest 302256408.

- ^ The Barefoot Beekeeper. Philip Chandler 2015 ISBN 9781326192259

- ^ Robinson, Gene E.; Visscher, P. Kirk (December 1984). "Effect of Low Temperature Narcosis on Honey Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Foraging Behavior". The Florida Entomologist. 67 (4): 568. doi:10.2307/3494466. JSTOR 3494466.

- ^ Cook, V. A. (1970). "Puff ball control of bees". N. Z. Jl. Agric. 120: 72–75.

- ^ Keewaydinoquay (1978). Puhpohwee for the people – a narrative account of some uses of fungi among Ahnishinaubeg: Cambridge, MA: Botanical Museum of Harvard University.

- ^ Wood, William F. (1983). "Anaesthesia of Honeybees by Smoke from the Pyrolysis of Puffballs and Keratin". J. Apicultural Research. 22 (2): 107–110. Bibcode:1983JApiR..22..107W. doi:10.1080/00218839.1983.11100569.

- ^ HELD, W.; STUCKI, M.; HEUSSER, C.; BLASER, K. (February 1989). "Production of Human Antibodies to Bee Venom Phospholipase A2 in Vitro". Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 29 (2): 203–209. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.1989.tb01117.x. PMID 2922572. S2CID 40844101.

- ^ a b Mayo Clinic Staff. "Bee Stings-Treatments and Drugs". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Southwick, Edward E.; Heldmaier, Gerhard (1987). "Temperature Control in Honey Bee Colonies". BioScience. 37 (6). American Institute of Biological Sciences: 395–399. doi:10.2307/1310562. JSTOR 1310562.

- ^ Gates, S.B.N. (1914). "The temperature of the bee colony". Bull. No. 96. USDA. pp. 1–19.

- ^ Southwick, Edward E.; Moritz, R.F.A. (1987). "Social control of air ventilation in colonies of honey bees, Apis mellifera". Journal of Insect Physiology. 33 (9): 623–626. Bibcode:1987JInsP..33..623S. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(87)90130-2.

- ^ Jarimi, Hasila; Tapia-Brito, Emmanuel; Riffat, Saffa (2020). "A Review on Thermoregulation Techniques in Honey Bees (Apis Mellifera) Beehive Microclimate and Its Similarities to the Heating and Cooling Management in Buildings". Future Cities and Environment. 6 (7): 4–5. Bibcode:2020FutCE...6....7J. doi:10.5334/fce.81. S2CID 225427905.

- ^ Root, A.I. (1978). ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture. Medina, Ohio: A.I. Root Company. pp. 682, 683.

- ^ Todorka, L.; Lyuben, L.; Ivanka, M.; Gergana, M.; Krasimira, T. (2020). "Thermal conductivity of the ceramic beehive". Machines Technologies Materials. 14 (2): 90–92.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge. Vol. I. London: Charles Knight. 1847. p. 894.

- ^ Jennifer Oldham. "Will Putting Honey Bees on Public Lands Threaten Native Bees?". e360.yale.edu. Yale School of the Environment. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Natural Beekeeping date". Archived from the original on 2020-11-27. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Conrad, Ross (2007) Natural Beekeeping: Organic approaches to modern apiculture, Chelsea Green, ISBN 978-1-60358-362-6

- ^ Chandler, Philip (2007). The Barefoot Beekeeper. Lulu. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4092-7114-7. Archived from the original on 2022-01-17. Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- ^ "Beekeeping with the Warré hive – Home". Warre.biobees.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ Tanguy, Marion (2010-06-23). "Can cities save our bees?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2017-02-25. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ Goodman Kurtz, Chaya (2010-06-03). "Bee-Friendly Landscaping". Networx. Archived from the original on 2012-08-06. Retrieved 2012-08-12.

- ^ Florida African Bee Action Plan Archived 2007-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, by Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. pp. 10.

- ^ "Wintering Techniques". Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- ^ "Synthetic Apiary – Biologically augmented digital fabrication". CreativeApplications.Net. Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- ^ "MIT's Mediated Matter Group Builds a Synthetic Apiary to Help Save Bees". Architect Magazine. 2016-10-17. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- ^ Amiri, Esmaeil; Strand, Micheline; Rueppell, Olav; Tarpy, David (2017-05-08). "Queen Quality and the Impact of Honey Bee Diseases on Queen Health: Potential for Interactions between Two Major Threats to Colony Health". Insects. 8 (2): 48. doi:10.3390/insects8020048. ISSN 2075-4450. PMC 5492062. PMID 28481294.

- ^ "Queen Bees Control Sex of Young After All". Science. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ Connor, Larry. "Queen Bee 101: Biology and Behavior of Queen Bees". Bee Culture. 138.7(2010): 48 – via Print.

- ^ "An Introduction to Queen Honey Bee Development". Penn State Extension. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rinderer, Thomas E. (2013-09-03). Bee Genetics and Breeding. Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-7003-6.

- ^ Root, A.I. (1978). ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture. Medina, Ohio: A. I. Root Company. pp. 610–611.

- ^ Snelgrove, L.E. (1935). Swarming, its Control and Prevention. Bleadon, England: Snelgrove & Smith.

- ^ Hepburn, H. Randall; Radloff, Sarah E. (2011-01-04). Honeybees of Asia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 448. ISBN 978-3-642-16422-4.

- ^ Frost, Elizabeth (2016-05-26). Queen Bee Breeding: AgGuide – A Practical Handbook (in Arabic). NSW Agriculture. ISBN 978-1-74256-922-2.

- ^ Mucignat-Caretta, Carla (2014-02-14). Neurobiology of Chemical Communication. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-5341-5.

- ^ Kearney, Hilary (2019-04-30). QueenSpotting: Meet the Remarkable Queen Bee and Discover the Drama at the Heart of the Hive; Includes 48 Queenspotting Challenges. Storey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-63586-038-2.

- ^ Grout, Roy A., ed. (1949). "Diseases of Adult bees". The hive and the honey bee: a new book on beekeeping which continues the tradition of "Langstroth on the hive and the honeybee". Dadant and Sons. p. 607. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Renee (2010). Honey Bee Colony Collapse Disorder.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (7 May 2013). "Beepocalypse Redux: Honeybees Are Still Dying – and We Still Don't Know Why". Time Science and Space. Time Inc. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Ingraham, Christopher (2015-07-23). "Call off the bee-pocalypse: U.S. honeybee colonies hit a 20-year high". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2015-12-01.

- ^ Sulborska, Aneta; Horeca, Beata; Cebrat, Malgorzata; Kowalczyk, Marek; Skrzypek, Tomasz H.; Kazimierczak, Waldemar; Trytek, Mariusz; Borsuk, Grzegorz (2019). "Microsporidia Nosema spp. – obligate bee parasites are transmitted by air". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 14376. Bibcode:2019NatSR...914376S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-50974-8. PMC 6779873. PMID 31591451. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Kwadha, Charles A.; Ong'amo, George O.; Ndegwa, Paul N.; Raina, Suresh K.; Fombong, Ayuka T. (2017-06-09). "The Biology and Control of the Greater Wax Moth, Galleria mellonella". Insects. 8 (2): 61. doi:10.3390/insects8020061. PMC 5492075. PMID 28598383.

- ^ Hood, Michael (2004). "The small hive beetle, Aethina tumida: a review" (PDF). Bee World. 85 (3): 51–59. doi:10.1080/0005772X.2004.11099624. S2CID 83632463. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2014.

- ^ Oliver, Randy (2017-01-30). "The Varroa Problem: Part 1 @ Scientific Beekeeping". scientificbeekeeping.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-14. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Denis; Roberts, John (2013), Standard methods for Tropilaelaps mites research

- ^ ""Tracheal mites" Tarsonemidae". Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. February 18, 2005. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ "What are some predators of the honeybee?". sciencing.com. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- ^ Castelo, Marcela K; Lazzari, Claudio R (2004-04-01). "Host-seeking behavior in larvae of the robber fly Mallophora ruficauda (Diptera: Asilidae)". Journal of Insect Physiology. 50 (4): 331–336. Bibcode:2004JInsP..50..331C. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.02.002. ISSN 0022-1910. PMID 15081826.

- ^ Nearman, Anthony; vanEngelsdorp, Dennis (2022-11-14). "Water provisioning increases caged worker bee lifespan and caged worker bees are living half as long as observed 50 years ago". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 18660. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1218660N. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-21401-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9663547. PMID 36376353. S2CID 253501180.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ^ "ARCHIVED – PDF document" (PDF). Statcan.gc.ca. 2010-05-17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-19. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ a b c d e "Economic aspects of beekeeping production in Croatia" (PDF). Veterinarski Arhiv. 79: 397–408. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ Bee Aware website Industry Archived 2016-05-14 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 13, 2016

- ^ "The prospects for beekeeping in the expanded EU" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-12-18.

- ^ a b c d Conradie, Beatrice & Nortjé, Bronwyn (July 2008). "SURVEY OF BEEKEEPING IN SOUTH AFRICA" (PDF). Centre for Social Science Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". Archived from the original on 2007-03-10.

- ^ "Beehive numbers by leading countries worldwide 2019". Statista. Archived from the original on 2021-02-03. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ "Global leading producers of honey worldwide 2019". Statista. Archived from the original on 2021-03-06. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ "Apiservices – Beekeeping – Apiculture – Denmark/Danemark". Beekeeping.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ "The Future of Bees and Honey Production in Arab Countries". Beekeeping.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ "Farm Commodity Programs: Honey" (PDF). nationalaglawcenter.org. National Honey Board. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Bees". Archived from the original on 2006-10-06.

- ^ Šljivić, Miljko. "Beekeeping in Serbia". Pcela.rs. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

External links

[edit]- The Moir Collection of rare beekeeping books consisting of 250 volumes including items published from 1525 at National Library of Scotland

- Dave Cushman's indexed website with glossary, about beekeeping

- Beekeeping for Beginners

- What’s The Oldest Honey Ever Found?