Anonymous (hacker group)

An emblem that is commonly associated with Anonymous. The "man without a head" represents anonymity and leaderless organization.[1] | |

| Formation | c. 2003 |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Purpose | |

| Membership | Decentralized affinity group |

| Part of a series on |

| Computer hacking |

|---|

Anonymous is a decentralized international activist and hacktivist collective and movement primarily known for its various cyberattacks against several governments, government institutions and government agencies, corporations and the Church of Scientology.

Anonymous originated in 2003 on the imageboard 4chan representing the concept of many online and offline community users simultaneously existing as an "anarchic", digitized "global brain" or "hivemind".[2][3][4] Anonymous members (known as anons) can sometimes be distinguished in public by the wearing of Guy Fawkes masks in the style portrayed in the graphic novel and film V for Vendetta.[5] Some anons also opt to mask their voices through voice changers or text-to-speech programs.

Dozens of people have been arrested for involvement in Anonymous cyberattacks in countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, the Netherlands, South Africa,[6] Spain, India, and Turkey. Evaluations of the group's actions and effectiveness vary widely. Supporters have called the group "freedom fighters"[7] and digital Robin Hoods,[8] while critics have described them as "a cyber lynch-mob"[9] or "cyber terrorists".[10] In 2012, Time called Anonymous one of the "100 most influential people" in the world.[11] Anonymous' media profile diminished by 2018,[12][13] but the group re-emerged in 2020 to support the George Floyd protests and other causes.[14][15]

Philosophy

The philosophy of Anonymous offers insight into a long-standing political question that has gone unanswered with often tragic consequences for social movements: what does a new form of collective politics look like that wishes to go beyond the identity of the individual subject in late capitalism?[16]

Internal dissent is also a regular feature of the group.[17] A website associated with the group describes it as "an Internet gathering" with "a very loose and decentralized command structure that operates on ideas rather than directives".[17] Gabriella Coleman writes of the group: "In some ways, it may be impossible to gauge the intent and motive of thousands of participants, many of who don't even bother to leave a trace of their thoughts, motivations, and reactions. Among those that do, opinions vary considerably."[18]

Broadly speaking, Anons oppose Internet censorship and control and the majority of their actions target governments, organizations, and corporations that they accuse of censorship. Anons were early supporters of the global Occupy movement and the Arab Spring.[19] Since 2008, a frequent subject of disagreement within Anonymous is whether members should focus on pranking and entertainment or more serious (and, in some cases, political) activism.[20][21]

We [Anonymous] just happen to be a group of people on the Internet who need—just kind of an outlet to do as we wish, that we wouldn't be able to do in regular society. ...That's more or less the point of it. Do as you wish. ... There's a common phrase: 'we are doing it for the lulz.'

— Trent Peacock, Search Engine: The Face of Anonymous, February 7, 2008.[22]

Because Anonymous has no leadership, no action can be attributed to the membership as a whole. Parmy Olson and others have criticized media coverage that presents the group as well-organized or homogeneous; Olson writes, "There was no single leader pulling the levers, but a few organizational minds that sometimes pooled together to start planning a stunt."[23] Some members protest using legal means, while others employ illegal measures such as DDoS attacks and hacking.[24] Membership is open to anyone who wishes to state they are a member of the collective;[25] British journalist Carole Cadwalladr of The Observer compared the group's decentralized structure to that of al-Qaeda: "If you believe in Anonymous, and call yourself Anonymous, you are Anonymous."[26] Olson, who formerly described Anonymous as a "brand", stated in 2012 that she now characterized it as a "movement" rather than a group: "anyone can be part of it. It is a crowd of people, a nebulous crowd of people, working together and doing things together for various purposes."[27]

The group's few rules include not disclosing one's identity, not talking about the group, and not attacking media.[28] Members commonly use the tagline "We are Anonymous. We are Legion. We do not forgive. We do not forget. Expect us."[29] Brian Kelly writes that three of the group's key characteristics are "(1) an unrelenting moral stance on issues and rights, regardless of direct provocation; (2) a physical presence that accompanies online hacking activity; and (3) a distinctive brand."[30]

Journalists have commented that Anonymous' secrecy, fabrications, and media awareness pose an unusual challenge for reporting on the group's actions and motivations.[31][32] Quinn Norton of Wired writes that: "Anons lie when they have no reason to lie. They weave vast fabrications as a form of performance. Then they tell the truth at unexpected and unfortunate times, sometimes destroying themselves in the process. They are unpredictable."[31] Norton states that the difficulties in reporting on the group cause most writers, including herself, to focus on the "small groups of hackers who stole the limelight from a legion, defied their values, and crashed violently into the law" rather than "Anonymous's sea of voices, all experimenting with new ways of being in the world".[31]

Arrests and trials

Since 2009, dozens of people have been arrested for involvement in Anonymous cyberattacks, in countries including the U.S., UK, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, and Turkey.[33] Anons generally protest these prosecutions and describe these individuals as martyrs to the movement.[34] The July 2011 arrest of LulzSec member Topiary became a particular rallying point, leading to a widespread "Free Topiary" movement.[35]

The first person to be sent to jail for participation in an Anonymous DDoS attack was Dmitriy Guzner, an American 19-year-old. He pleaded guilty to "unauthorized impairment of a protected computer" in November 2009 and was sentenced to 366 days in U.S. federal prison.[36][37]

On June 13, 2011, officials in Turkey arrested 32 individuals that were allegedly involved in DDoS attacks on Turkish government websites. These members of Anonymous were captured in different cities of Turkey including Istanbul and Ankara. According to PC Magazine, these individuals were arrested after they attacked websites as a response to the Turkish government demand to ISPs to implement a system of filters that many have perceived as censorship.[38][39]

Chris Doyon (alias "Commander X"), a self-described leader of Anonymous, was arrested in September 2011 for a cyberattack on the website of Santa Cruz County, California.[40][41] He jumped bail in February 2012 and fled across the border into Canada.[41]

In September 2012, journalist and Anonymous associate Barrett Brown, known for speaking to media on behalf of the group, was arrested hours after posting a video that appeared to threaten FBI agents with physical violence. Brown was subsequently charged with 17 offenses, including publishing personal credit card information from the Stratfor hack.[42]

Operation Avenge Assange

Several law enforcement agencies took action after Anonymous' Operation Avenge Assange.[43] In January 2011, British police arrested five male suspects between the ages of 15 and 26 with suspicion of participating in Anonymous DDoS attacks.[44] During July 19–20, 2011, as many as 20 or more arrests were made of suspected Anonymous hackers in the US, UK, and Netherlands. According to the statements of U.S. officials, suspects' homes were raided and suspects were arrested in Alabama, Arizona, California, Colorado, Washington DC, Florida, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Mexico, and Ohio. Additionally, a 16-year-old boy was held by the police in south London on suspicion of breaching the Computer Misuse Act 1990, and four were held in the Netherlands.[45][46][47][48]

AnonOps admin Christopher Weatherhead (alias "Nerdo"), a 22-year-old who had reportedly been intimately involved in organizing DDoS attacks during "Operation Payback",[49] was convicted by a UK court on one count of conspiracy to impair the operation of computers in December 2012. He was sentenced to 18 months' imprisonment. Ashley Rhodes, Peter Gibson, and another male had already pleaded guilty to the same charge for actions between August 2010 and January 2011.[49][50]

Analysis

Evaluations of Anonymous' actions and effectiveness vary widely. In a widely shared post, blogger Patrick Gray wrote that private security firms "secretly love" the group for the way in which it publicizes cyber security threats.[51] Anonymous is sometimes stated to have changed the nature of protesting,[8][9] and in 2012, Time called it one of the "100 most influential people" in the world.[11]

In 2012, Public Radio International reported that the U.S. National Security Agency considered Anonymous a potential national security threat and had warned the president that it could develop the capability to disable parts of the U.S. power grid.[52] In contrast, CNN reported in the same year that "security industry experts generally don't consider Anonymous a major player in the world of cybercrime" due to the group's reliance on DDoS attacks that briefly disabled websites rather than the more serious damage possible through hacking. One security consultant compared the group to "a jewelry thief that drives through a window, steal jewels, and rather than keep them, waves them around and tosses them out to a crowd ... They're very noisy, low-grade crimes."[53] In its 2013 Threats Predictions report, McAfee wrote that the technical sophistication of Anonymous was in decline and that it was losing supporters due to "too many uncoordinated and unclear operations".[54]

Graham Cluley, a security expert for Sophos, argued that Anonymous' actions against child porn websites hosted on a darknet could be counterproductive, commenting that while their intentions may be good, the removal of illegal websites and sharing networks should be performed by the authorities, rather than Internet vigilantes.[55] Some commentators also argued that the DDoS attacks by Anonymous following the January 2012 Stop Online Piracy Act protests had proved counterproductive. Molly Wood of CNET wrote that "[i]f the SOPA/PIPA protests were the Web's moment of inspiring, non-violent, hand-holding civil disobedience, #OpMegaUpload feels like the unsettling wave of car-burning hooligans that sweep in and incite the riot portion of the play."[56] Dwight Silverman of the Houston Chronicle concurred, stating that "Anonymous' actions hurt the movement to kill SOPA/PIPA by highlighting online lawlessness."[57] The Oxford Internet Institute's Joss Wright wrote that "In one sense the actions of Anonymous are themselves, anonymously and unaccountably, censoring websites in response to positions with which they disagree."[58]

Gabriella Coleman has compared the group to the trickster archetype[59] and said that "they dramatize the importance of anonymity and privacy in an era when both are rapidly eroding. Given that vast databases track us, given the vast explosion of surveillance, there's something enchanting, mesmerizing and at a minimum thought-provoking about Anonymous' interventions".[60] When asked what good Anonymous had done for the world, Parmy Olson replied:

In some cases, yes, I think it has in terms of some of the stuff they did in the Middle East supporting the pro-democracy demonstrators. But a lot of bad things too, unnecessarily harassing people – I would class that as a bad thing. DDOSing the CIA website, stealing customer data and posting it online just for shits and giggles is not a good thing.[27]

Quinn Norton of Wired wrote of the group in 2011:

I will confess up front that I love Anonymous, but not because I think they're the heroes. Like Alan Moore's character V who inspired Anonymous to adopt the Guy Fawkes mask as an icon and fashion item, you're never quite sure if Anonymous is the hero or antihero. The trickster is attracted to change and the need for change, and that's where Anonymous goes. But they are not your personal army – that's Rule 44 – yes, there are rules. And when they do something, it never goes quite as planned. The internet has no neat endings.[59]

Furthermore, Landers assessed the following in 2008:

Anonymous is the first internet-based super-consciousness. Anonymous is a group, in the sense that a flock of birds is a group. How do you know they’re a group? Because they’re travelling in the same direction. At any given moment, more birds could join, leave, peel off in another direction entirely.[61]

Media portrayal

Sam Esmail shared in an interview with Motherboard that he was inspired by Anonymous when creating the USA Network hacktivist drama, Mr. Robot.[62] Furthermore, Wired calls the "Omegas", a fictitious hacker group in the show, "a clear reference to the Anonymous offshoot known as LulzSec".[63] In the TV series Elementary a hacktivist collective called "Everyone" plays a recurring role; there are several hints and similarities to Anonymous.[64]

History

4chan raids (2003–2007)

The name Anonymous itself is inspired by the perceived anonymity under which users post images and comments on the Internet. Usage of the term Anonymous in the sense of a shared identity began on imageboards, particularly the /b/ board of 4chan, dedicated to random content and to raiding other websites.[66] A tag of Anonymous is assigned to visitors who leave comments without identifying the originator of the posted content. Users of imageboards sometimes jokingly acted as if Anonymous was a single individual. The concept of the Anonymous entity advanced in 2004 when an administrator on the 4chan image board activated a "Forced_Anon" protocol that signed all posts as Anonymous.[67] As the popularity of imageboards increased, the idea of Anonymous as a collective of unnamed individuals became an Internet meme.[68]

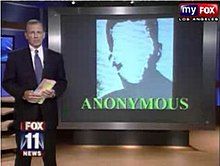

Users of 4chan's /b/ board would occasionally join into mass pranks or raids.[66] In a raid on July 12, 2006, for example, large numbers of 4chan readers invaded the Finnish social networking site Habbo Hotel with identical avatars; the avatars blocked regular Habbo members from accessing the digital hotel's pool, stating it was "closed due to fail and AIDS".[69] Future LulzSec member Topiary became involved with the site at this time, inviting large audiences to listen to his prank phone calls via Skype.[70][a] Due to the growing traffic on 4chan's board, users soon began to plot pranks off-site using Internet Relay Chat (IRC).[72] These raids resulted in the first mainstream press story on Anonymous, a report by Fox station KTTV in Los Angeles, California in the U.S. The report called the group "hackers on steroids", "domestic terrorists", and an "Internet hate machine".[65][73]

Encyclopedia Dramatica (2004–present)

Encyclopedia Dramatica was founded in 2004 by Sherrod DeGrippo, initially as a means of documenting gossip related to LiveJournal, but it quickly was adopted as a major platform by Anonymous for parody and other purposes.[74] The not safe for work site celebrates a subversive "trolling culture", and documents Internet memes, culture, and events, such as mass pranks, trolling events, "raids", large-scale failures of Internet security, and criticism of Internet communities that are accused of self-censorship to gain prestige or positive coverage from traditional and established media outlets. Journalist Julian Dibbell described Encyclopedia Dramatica as the site "where the vast parallel universe of Anonymous in-jokes, catchphrases, and obsessions is lovingly annotated, and you will discover an elaborate trolling culture: Flamingly racist and misogynist content lurks throughout, all of it calculated to offend."[74] The site also played a role in the anti-Scientology campaign of Project Chanology.[75]

On April 14, 2011, the original URL of the site was redirected to a new website named Oh Internet that bore little resemblance to Encyclopedia Dramatica. Parts of the ED community harshly criticized the changes.[76] In response, Anonymous launched "Operation Save ED" to rescue and restore the site's content.[77] The Web Ecology Project made a downloadable archive of former Encyclopedia Dramatica content.[78][79] The site's reincarnation was initially hosted at encyclopediadramatica.ch on servers owned by Ryan Cleary, who later was arrested in relation to attacks by LulzSec against Sony.[80]

Project Chanology (2008)

Anonymous first became associated with hacktivism[b] in 2008 following a series of actions against the Church of Scientology known as Project Chanology. On January 15, 2008, the gossip blog Gawker posted a video in which celebrity Scientologist Tom Cruise praised the religion;[81] and the Church responded with a cease-and-desist letter for violation of copyright.[82] 4chan users organized a raid against the Church in retaliation, prank-calling its hotline, sending black faxes designed to waste ink cartridges, and launching DDoS attacks against its websites.[83][84]

The DDoS attacks were at first carried out with the Gigaloader and JMeter applications. Within a few days, these were supplanted by the Low Orbit Ion Cannon (LOIC), a network stress-testing application allowing users to flood a server with TCP or UDP packets. The LOIC soon became a signature weapon in the Anonymous arsenal; however, it would also lead to a number of arrests of less experienced Anons who failed to conceal their IP addresses.[85] Some operators in Anonymous IRC channels incorrectly told or lied to new volunteers that using the LOIC carried no legal risk.[86][87]

During the DDoS attacks, a group of Anons uploaded a YouTube video in which a robotic voice speaks on behalf of Anonymous, telling the "leaders of Scientology" that "For the good of your followers, for the good of mankind—for the laughs—we shall expel you from the Internet."[88][89] Within ten days, the video had attracted hundreds of thousands of views.[89]

With more than 10 thousand followers on their IRC server waiting for instructions, they felt they had to come up with something, and got the idea of a worldwide protest. Because they both wanted to use a symbol or image to unify the protests, and because all protesters were supposed to be anonymous, it was decided to use a mask. Due to shipment problems caused by the short amount of time to prepare, they improvised and called all the costume and comic book-shops in the major cities around the world, and found that the only mask available in all the cities was the Guy Fawkes mask from the graphic novel and film V for Vendetta, in which an anarchist revolutionary battles a totalitarian government. The suggestion of the choice of mask was well received. On February 10, thousands of Anonymous joined simultaneous protests at Church of Scientology facilities in 142 cities in 43 countries.[90][91][92] The stylized Guy Fawkes masks soon became a popular symbol for Anonymous.[93] In-person protests against the Church continued throughout the year, including "Operation Party Hard" on March 15 and "Operation Reconnect" on April 12.[94][95][96] However, by mid-year, they were drawing far fewer protesters, and many of the organizers in IRC channels had begun to drift away from the project.[97]

Operation Payback (2010)

By the start of 2009, Scientologists had stopped engaging with protesters and had improved online security, and actions against the group had largely ceased. A period of infighting followed between the politically engaged members (called "moralfags" in the parlance of 4chan) and those seeking to provoke for entertainment (trolls).[98] By September 2010, the group had received little publicity for a year and faced a corresponding drop in member interest; its raids diminished greatly in size and moved largely off of IRC channels, organizing again from the chan boards, particularly /b/.[99]

In September 2010, however, Anons became aware of Aiplex Software, an Indian software company that contracted with film studios to launch DDoS attacks on websites used by copyright infringers, such as The Pirate Bay.[100][99] Coordinating through IRC, Anons launched a DDoS attack on September 17 that shut down Aiplex's website for a day. Primarily using LOIC, the group then targeted the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), successfully bringing down both sites.[101] On September 19, future LulzSec member Mustafa Al-Bassam (known as "Tflow") and other Anons hacked the website of Copyright Alliance, an anti-infringement group, and posted the name of the operation: "Payback Is A Bitch", or "Operation Payback" for short.[102] Anons also issued a press release, stating:

Anonymous is tired of corporate interests controlling the internet and silencing the people’s rights to spread information, but more importantly, the right to SHARE with one another. The RIAA and the MPAA feign to aid the artists and their cause; yet they do no such thing. In their eyes is not hope, only dollar signs. Anonymous will not stand this any longer.[103]

As IRC network operators were beginning to shut down networks involved in DDoS attacks, Anons organized a group of servers to host an independent IRC network, titled AnonOps.[104] Operation Payback's targets rapidly expanded to include the British law firm ACS:Law,[105] the Australian Federation Against Copyright Theft,[106] the British nightclub Ministry of Sound,[107] the Spanish copyright society Sociedad General de Autores y Editores,[108] the U.S. Copyright Office,[109] and the website of Gene Simmons of Kiss.[110] By October 7, 2010, total downtime for all websites attacked during Operation Payback was 537.55 hours.[110]

In November 2010, the organization WikiLeaks began releasing hundreds of thousands of leaked U.S. diplomatic cables. In the face of legal threats against the organization by the U.S. government, Amazon.com booted WikiLeaks from its servers, and PayPal, MasterCard, and Visa cut off service to the organization.[111] Operation Payback then expanded to include "Operation Avenge Assange", and Anons issued a press release declaring PayPal a target.[112] Launching DDoS attacks with the LOIC, Anons quickly brought down the websites of the PayPal blog; PostFinance, a Swiss financial company denying service to WikiLeaks; EveryDNS, a web-hosting company that had also denied service; and the website of U.S. Senator Joe Lieberman, who had supported the push to cut off services.[113]

On December 8, Anons launched an attack against PayPal's main site. According to Topiary, who was in the command channel during the attack, the LOIC proved ineffective, and Anons were forced to rely on the botnets of two hackers for the attack, marshaling hijacked computers for a concentrated assault.[114] Security researcher Sean-Paul Correll also reported that the "zombie computers" of involuntary botnets had provided 90% of the attack.[115] Topiary states that he and other Anons then "lied a bit to the press to give it that sense of abundance", exaggerating the role of the grassroots membership. However, this account was disputed.[116]

The attacks brought down PayPal.com for an hour on December 8 and another brief period on December 9.[117] Anonymous also disrupted the sites for Visa and MasterCard on December 8.[118] Anons had announced an intention to bring down Amazon.com as well, but failed to do so, allegedly because of infighting with the hackers who controlled the botnets.[119] PayPal estimated the damage to have cost the company US$5.5 million. It later provided the IP addresses of 1,000 of its attackers to the FBI, leading to at least 14 arrests.[120] On Thursday, December 5, 2013, 13 of the PayPal 14 pleaded guilty to taking part in the attacks.[121]

2011–2012

In the years following Operation Payback, targets of Anonymous protests, hacks, and DDoS attacks continued to diversify. Beginning in January 2011, Anons took a number of actions known initially as Operation Tunisia in support of Arab Spring movements. Tflow created a script that Tunisians could use to protect their web browsers from government surveillance, while fellow future LulzSec member Hector Xavier Monsegur (alias "Sabu") and others allegedly hijacked servers from a London web-hosting company to launch a DDoS attack on Tunisian government websites, taking them offline. Sabu also used a Tunisian volunteer's computer to hack the website of Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi, replacing it with a message from Anonymous.[122] Anons also helped Tunisian dissidents share videos online about the uprising.[123] In Operation Egypt, Anons collaborated with the activist group Telecomix to help dissidents access government-censored websites.[123] Sabu and Topiary went on to participate in attacks on government websites in Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, Jordan, and Zimbabwe.[124]

Tflow, Sabu, Topiary, and Ryan Ackroyd (known as "Kayla") collaborated in February 2011 on a cyber-attack against Aaron Barr, CEO of the computer security firm HBGary Federal, in retaliation for his research on Anonymous and his threat to expose members of the group. Using a SQL injection weakness, the four hacked the HBGary site, used Barr's captured password to vandalize his Twitter feed with racist messages, and released an enormous cache of HBGary's e-mails in a torrent file on Pirate Bay.[125] The e-mails stated that Barr and HBGary had proposed to Bank of America a plan to discredit WikiLeaks in retaliation for a planned leak of Bank of America documents,[126] and the leak caused substantial public relations harm to the firm as well as leading one U.S. congressman to call for a congressional investigation.[127] Barr resigned as CEO before the end of the month.[128]

Several attacks by Anons have targeted organizations accused of homophobia. In February 2011, an open letter was published on AnonNews.org threatening the Westboro Baptist Church, an organization based in Kansas in the U.S. known for picketing funerals with signs reading "God Hates Fags".[129] During a live radio current affairs program in which Topiary debated church member Shirley Phelps-Roper, CosmoTheGod hacked one of the organization's websites.[130][131] After the church announced its intentions in December 2012 to picket the funerals of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting victims, CosmoTheGod published the names, phone numbers, and e-mail and home addresses of church members and brought down GodHatesFags.com with a DDoS attack.[132] In August 2012, Anons hacked the site of Ugandan Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi in retaliation for the Parliament of Uganda's consideration of an anti-homosexuality law permitting capital punishment.[133]

In April 2011, Anons launched a series of attacks against Sony in retaliation for trying to stop hacks of the PlayStation 3 game console. More than 100 million Sony accounts were compromised, and the Sony services Qriocity and PlayStation Network were taken down for a month apiece by cyberattacks.[134]

In July 2011, Anonymous announced the launch of its social media platform Anonplus.[135] This came after Anonymous' presence was removed from Google+.[136] The site was later hacked by a Turkish hackers group who placed a message on the front page and replaced its logo with a picture of a dog.[137]

In August 2011, Anons launched an attack against BART in San Francisco, which they dubbed #OpBart. The attack, made in response to the killing of Charles Hill a month prior, resulted in customers' personal information leaked onto the group's website.[138]

When the Occupy Wall Street protests began in New York City in September 2011, Anons were early participants and helped spread the movement to other cities such as Boston.[19] In October, some Anons attacked the website of the New York Stock Exchange while other Anons publicly opposed the action via Twitter.[53] Some Anons also helped organize an Occupy protest outside the London Stock Exchange on May 1, 2012.[139]

Anons launched Operation Darknet in October 2011, targeting websites hosting child pornography. In particular, the group hacked a child pornography site called "Lolita City" hosted by Freedom Hosting, releasing 1,589 usernames from the site. Anons also said that they had disabled forty image-swapping pedophile websites that employed the anonymity network Tor.[140] In 2012, Anons leaked the names of users of a suspected child porn site in OpDarknetV2.[141] Anonymous launched the #OpPedoChat campaign on Twitter in 2012 as a continuation of Operation Darknet. In attempt to eliminate child pornography from the internet, the group posted the emails and IP addresses of suspected pedophiles on the online forum PasteBin.[142][143]

In 2011, the Koch Industries website was attacked following their attack upon union members, resulting in their website being made inaccessible for 15 minutes. In 2013, one member, a 38-year-old truck driver, pleaded guilty when accused of participating in the attack for a period of one minute, and received a sentence of two years federal probation, and ordered to pay $183,000 restitution, the amount Koch stated they paid a consultancy organization, despite this being only a denial of service attack.[144]

On January 19, 2012, the U.S. Department of Justice shut down the file-sharing site Megaupload on allegations of copyright infringement. Anons responded with a wave of DDoS attacks on U.S. government and copyright organizations, shutting down the sites for the RIAA, MPAA, Broadcast Music, Inc., and the FBI.[145]

In April 2012, Anonymous hacked 485 Chinese government websites, some more than once, to protest the treatment of their citizens. They urged people to "fight for justice, fight for freedom, [and] fight for democracy".[146][147][148]

In 2012, Anonymous launched Operation Anti-Bully: Operation Hunt Hunter in retaliation to Hunter Moore's revenge porn site, "Is Anyone Up?" Anonymous crashed Moore's servers and publicized much of his personal information online, including his social security number. The organization also published the personal information of Andrew Myers, the proprietor of "Is Anyone Back", a copycat site of Moore's "Is Anyone Up?"[149]

In response to Operation Pillar of Defense, a November 2012 Israeli military operation in the Gaza Strip, Anons took down hundreds of Israeli websites with DDoS attacks.[150] Anons pledged another "massive cyberassault" against Israel in April 2013 in retaliation for its actions in Gaza, promising to "wipe Israel off the map of the Internet".[151] However, its DDoS attacks caused only temporary disruptions, leading cyberwarfare experts to suggest that the group had been unable to recruit or hire botnet operators for the attack.[152][153]

2013

On November 5, 2013, Anonymous protesters gathered around the world for the Million Mask March. Demonstrations were held in 400 cities around the world to coincide with Guy Fawkes Night.[154]

Operation Safe Winter was an effort to raise awareness about homelessness through the collection, collation, and redistribution of resources. This program began on November 7, 2013[155] after an online call to action from Anonymous UK. Three missions using a charity framework were suggested in the original global spawning a variety of direct actions from used clothing drives to pitch in community potlucks feeding events in the UK, US and Turkey.[156] The #OpSafeWinter call to action quickly spread through the mutual aid communities like Occupy Wall Street[157] and its offshoot groups like the open-source-based OccuWeather.[158] With the addition of the long-term mutual aid communities of New York City and online hacktivists in the US, it took on an additional three suggested missions.[159] Encouraging participation from the general public, this operation has raised questions of privacy and the changing nature of the Anonymous community's use of monikers. The project to support those living on the streets while causing division in its own online network has been able to partner with many efforts and organizations not traditionally associated with Anonymous or online activists.

2014

In the wake of the fatal police shooting of unarmed African-American Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, "Operation Ferguson"—a hacktivist organization that claimed to be associated with Anonymous—organized cyberprotests against police, setting up a website and a Twitter account to do so.[160] The group promised that if any protesters were harassed or harmed, they would attack the city's servers and computers, taking them offline.[160] City officials said that e-mail systems were targeted and phones died, while the Internet crashed at the City Hall.[160][161] Prior to August 15, members of Anonymous corresponding with Mother Jones said that they were working on confirming the identity of the undisclosed police officer who shot Brown and would release his name as soon as they did.[162] On August 14, Anonymous posted on its Twitter feed what it claimed was the name of the officer involved in the shooting.[163][164] However, police said the identity released by Anonymous was incorrect.[165] Twitter subsequently suspended the Anonymous account from its service.[166]

It was reported on November 19, 2014, that Anonymous had declared cyber war on the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) the previous week, after the KKK had made death threats following the Ferguson riots. They hacked the KKK's Twitter account, attacked servers hosting KKK sites, and started to release the personal details of members.[167]

On November 24, 2014, Anonymous shut down the Cleveland city website and posted a video after Tamir Rice, a twelve-year-old boy armed only with a BB gun, was shot to death by a police officer in a Cleveland park.[168] Anonymous also used BeenVerified to uncover the phone number and address of a police officer involved in the shooting.[169]

2015

In January 2015, Anonymous released a video and a statement via Twitter condemning the attack on Charlie Hebdo, in which 12 people, including eight journalists, were fatally shot. The video, claiming that it is "a message for al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and other terrorists", was uploaded to the group's Belgian account.[170] The announcement stated that "We, Anonymous around the world, have decided to declare war on you, the terrorists" and promises to avenge the killings by "shut[ting] down your accounts on all social networks."[171] On January 12, they brought down a website that was suspected to belong to one of these groups.[172] Critics of the action warned that taking down extremists' websites would make them harder to monitor.[173]

On June 17, 2015, Anonymous claimed responsibility for a Denial of Service attack against Canadian government websites in protest of the passage of bill C-51—an anti-terror legislation that grants additional powers to Canadian intelligence agencies.[174] The attack temporarily affected the websites of several federal agencies.

On October 28, 2015, Anonymous announced that it would reveal the names of up to 1,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan and other affiliated groups, stating in a press release, "You are terrorists that hide your identities beneath sheets and infiltrate society on every level. The privacy of the Ku Klux Klan no longer exists in cyberspace."[175] On November 2, a list of 57 phone numbers and 23 email addresses (that allegedly belong to KKK members) was reportedly published and received media attention.[176] However, a tweet from the "@Operation_KKK" Twitter account the same day denied it had released that information[177][178][179] The group stated it planned to, and later did, reveal the names on November 5.[180]

Since 2013, Saudi Arabian hacktivists have been targeting government websites protesting the actions of the regime.[181] These actions have seen attacks supported by the possibly Iranian backed Yemen Cyber Army.[182] An offshoot of Anonymous self-described as Ghost Security or GhostSec started targeting Islamic State-affiliated websites and social media handles.[183][184]

In November 2015, Anonymous announced a major, sustained operation against ISIS following the November 2015 Paris attacks,[185] declaring: "Anonymous from all over the world will hunt you down. You should know that we will find you and we will not let you go."[186][187] ISIS responded on Telegram by calling them "idiots", and asking "What they gonna to [sic] hack?"[188][189] By the next day, however, Anonymous claimed to have taken down 3,824 pro-ISIS Twitter accounts, and by the third day more than 5,000,[190] and to have doxxed ISIS recruiters.[191] A week later, Anonymous increased their claim to 20,000 pro-ISIS accounts and released a list of the accounts.[192][193] The list included the Twitter accounts of Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, The New York Times, and BBC News. The BBC reported that most of the accounts on the list appeared to be still active.[194] A spokesman for Twitter told The Daily Dot that the company is not using the lists of accounts being reported by Anonymous, as they have been found to be "wildly inaccurate" and include accounts used by academics and journalists.[195]

In 2015, a group that claimed to be affiliated with Anonymous, calling themselves as AnonSec, claimed to have hacked and gathered almost 276 GB of data from NASA servers including NASA flight and radar logs and videos, and also multiple documents related to ongoing research.[196] AnonSec group also claimed gaining access of a Global Hawk Drone of NASA, and released some video footage purportedly from the drone's cameras. A part of the data was released by AnonSec on Pastebin service, as an Anon Zine.[197] NASA has denied the hack, asserting that the control of the drones were never compromised, but has acknowledged that the photos released along with the content are real photographs of its employees, but that most of these data are already available in the public domain.[198]

2016

The Blink Hacker Group, associating themselves with the Anonymous group, claimed to have hacked the Thailand prison websites and servers.[199] The compromised data has been shared online, with the group claiming that they give the data back to Thailand Justice and the citizens of Thailand as well. The hack was done in response to news from Thailand about the mistreatment of prisoners in Thailand.[200]

A group calling themselves Anonymous Africa launched a number of DDoS attacks on websites associated with the controversial South African Gupta family in mid-June 2016. Gupta-owned companies targeted included the websites of Oakbay Investments, The New Age, and ANN7. The websites of the South African Broadcasting Corporation, the political party Economic Freedom Fighters, and Zimbabwe's Zanu-PF were also attacked for "politicising racism."[201]

Late 2010s

In late 2017, the QAnon conspiracy theory first emerged on 4chan, and adherents used similar terminology and branding to Anonymous. In response, in 2018, anti-Trump members of Anonymous warned that QAnon was stealing the collective's branding and vowed to oppose the theory.[202][203][13]

However, in 2017, some members stood against similar groups[202][203][204] and QAnon itself.[202]

2020

In February 2020, Anonymous hacked the United Nations' website and created a page for Taiwan, a country which has not had a seat at the UN since 1971.[205][206] The hacked page featured the Flag of Taiwan, the KMT emblem, a Taiwan Independence flag, and the Anonymous logo along with a caption.[205][207] The hacked server belonged to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.[205]

In the wake of protests across the U.S. following the murder of George Floyd, Anonymous released a video on Facebook as well as sending it out to the Minneapolis Police Department on May 28, 2020, titled "Anonymous Message To The Minneapolis Police Department", in which they state that they are going to seek revenge on the Minneapolis Police Department, and "expose their crimes to the world".[208][non-primary source needed][209] According to Bloomberg, the video was initially posted on an unconfirmed Anonymous Facebook page on May 28.[210] According to BBC News, that same Facebook page had no notoriety and published videos of dubious content linked to UFOs and "China's plan to take over the world". It gained repercussions after the video about George Floyd was published[211] and the Minneapolis police website, which is responsible for the police officer, was down.[212] Later, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz said that every computer in the region suffered a sophisticated attack.[213] According to BBC News, the attack on the police website using DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) was unsophisticated.[211] According to researcher Troy Hunt, these breaches of the site may have happened from old credentials. Regarding unverified Twitter posts that also went viral, where radio stations of police officers playing music and preventing communication are shown, experts point out that this is unlikely to be due to a hack attack – if they are real.[211] Later, it was confirmed by CNET that the leaks made from the police website are false and that someone is taking advantage of the repercussions of George Floyd's murder to spread misinformation.[214]

On June 19, 2020, Anonymous published BlueLeaks, sometimes referred to by the Twitter hashtag #BlueLeaks, 269.21 gigabytes of internal U.S. law enforcement data through the activist group Distributed Denial of Secrets, which called it the "largest published hack of American law enforcement agencies".[215] The data — internal intelligence, bulletins, emails, and reports — was produced between August 1996 and June 2020[216] by more than 200 law enforcement agencies, which provided it to fusion centers. It was obtained through a security breach of Netsential, a web developer that works with fusion centers and law enforcement.[217] In Maine, legislators took interest in BlueLeaks thanks to details about the Maine Information and Analysis Center, which is under investigation. The leaks showed the fusion center was spying on and keeping records on people who had been legally protesting or had been "suspicious" but committed no crime.[218]

In 2020, Anonymous started cyber-attacks against the Nigerian government. They started the operation to support the #EndSARS movement in Nigeria. The group's attacks were tweeted by a member of Anonymous called LiteMods. The websites of EFCC, INEC and various other Nigerian government websites were taken-down with DDoS attacks. The websites of some banks were compromised.[219][220][221][222]

2021

The Texas Heartbeat Act, a law which bans abortions after six weeks of pregnancy, came into effect in Texas on September 1, 2021. The law relies on private citizens to file civil lawsuits against anyone who performs or induces an abortion, or aids and abets one, once "cardiac activity" in an embryo can be detected via transvaginal ultrasound, which is usually possible beginning at around six weeks of pregnancy.[223] Shortly after the law came into effect, anti-abortion organizations set up websites to collect "whistleblower" reports of suspected violators of the bill.[224]

On September 3, Anonymous announced "Operation Jane", a campaign focused on stymying those who attempted to enforce the law by "exhaust[ing] the investigational resources of bounty hunters, their snitch sites, and online gathering spaces until no one is able to maintain data integrity".[224] On September 11, the group hacked the website of the Republican Party of Texas, replacing it with text about Anonymous, an invitation to join Operation Jane, and a Planned Parenthood donation link.[225]

On September 13, Anonymous released a large quantity of private data belonging to Epik, a domain registrar and web hosting company known for providing services to websites that host far-right, neo-Nazi, and other extremist content.[226] Epik had briefly provided services to an abortion "whistleblower" website run by the anti-abortion Texas Right to Life organization, but the reporting form went offline on September 4 after Epik told the group they had violated their terms of service by collecting private information about third parties.[227] The data included domain purchase and transfer details, account credentials and logins, payment history, employee emails, and unidentified private keys.[228] The hackers claimed they had obtained "a decade's worth of data" which included all customers and all domains ever hosted or registered through the company, and which included poorly encrypted passwords and other sensitive data stored in plaintext.[228][229] Later on September 13, the Distributed Denial of Secrets (DDoSecrets) organization said they were working to curate the allegedly leaked data for more accessible download, and said that it consisted of "180 gigabytes of user, registration, forwarding and other information".[230] Publications including The Daily Dot and The Record by Recorded Future subsequently confirmed the veracity of the hack and the types of data that had been exposed.[231][229] Anonymous released another leak on September 29, this time publishing bootable disk images of Epik's servers;[232][233] more disk images as well as some leaked documents from the Republican Party of Texas appeared on October 4.[234]

2022

On February 25, 2022, Twitter accounts associated with Anonymous declared that they had launched a 'cyber operations' against the Russian Federation, in retaliation for the invasion of Ukraine ordered by Russian president Vladimir Putin. The group later temporarily disabled websites such as RT.com and the website of the Defence Ministry along with other state owned websites.[235][236][237][238][239] Anonymous also leaked 200 GB worth of emails from the Belarusian weapons manufacturer Tetraedr, which provided logistical support for Russia in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[240] Anonymous also hacked into Russian TV channels and played Ukrainian music[241] through them and showed uncensored news of events in Ukraine.[242]

Operation Russia

On March 7, 2022, Anonymous actors DepaixPorteur and TheWarriorPoetz declared on Twitter[243] that they hacked 400 Russian surveillance cameras and broadcast them on a website.[244] They call this operation "Russian Camera Dump".[243]

Between March 25, 2022, and June 1, 2022, DDoSecrets collected hundreds and hundreds of gigabytes and millions of emails allegedly from the Central Bank of Russia,[245] Capital Legal Services,[246] All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK),[247] Aerogas,[248] Blagoveshchensk City Administration,[246] Continent Express,[249] Gazregion,[250] GUOV i GS - General Dept. of Troops and Civil Construction,[251] Accent Capital,[252] ALET/АЛЕТ, CorpMSP,[253] Nikolai M. Knipovich Polar Research Institute of Marine Fisheries and Oceanography (PINRO),[254] the Achinsk City Government,[254][255] SOCAR Energoresource,[254][256] Metprom Group LLC,[257] and the Vyberi Radio / Выбери Радио group,[258] all of which were allegedly hacked by Anonymous and Anonymous aligned NB65.[246]

Iranian protests

On September 18, 2022, YourAnonSpider hacked the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution of Iran's official webpage belonging to Ali Khamenei in retaliation to the death of Mahsa Amini.[259] Anonymous launched a cyber operation against the Iranian government for the alleged murder of Mahsa Amini. Anonymous launched distributed denial of service (DDOS) attacks against Iran's government and state-owned websites.[260] On September 23, 2022, a hacktivist named "Edaalate Ali" hacked Iran's state TV government channel during the middle of broadcast and released CCTV footage of Iran's prison facilities.[261][262] On October 23, 2022, an Iranian hacker group known as "Black Reward" published confidential files and documents email system belonging to Iran's nuclear program.[263][264] Black Reward announced on their Telegram channel that they have hacked into 324 emails which contained more than a hundred thousand messages and over 50 gigabytes of files.[265] A hacktivist group by the name "Lab Dookhtegan" published the Microsoft Excel macros, PowerShell exploits APT34 reportedly used to target organizations across the world.[266][267][268]

Chinese protests

In response to the 2022 COVID-19 protests in China, "Anonymous OpIran" launched Operation White Paper, attacked and took down Chinese government controlled websites, and leaked some Chinese government officials' personal information.[269]

Related groups

LulzSec

In May 2011, the small group of Anons behind the HBGary Federal hack—including Tflow, Topiary, Sabu, and Kayla—formed the hacker group "Lulz Security", commonly abbreviated "LulzSec". The group's first attack was against Fox.com, leaking several passwords, LinkedIn profiles, and the names of 73,000 X Factor contestants. In May 2011, members of Lulz Security gained international attention for hacking into the American Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) website. They stole user data and posted a fake story on the site that claimed that rappers Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls were still alive and living in New Zealand.[270] LulzSec stated that some of its hacks, including its attack on PBS, were motivated by a desire to defend WikiLeaks and its informant Chelsea Manning.[271]

In June 2011, members of the group claimed responsibility for an attack against Sony Pictures that took data that included "names, passwords, e-mail addresses, home addresses and dates of birth for thousands of people."[272] In early June, LulzSec hacked into and stole user information from the pornography website www.pron.com. They obtained and published around 26,000 e-mail addresses and passwords.[273] On June 14, 2011, LulzSec took down four websites by request of fans as part of their "Titanic Take-down Tuesday". These websites were Minecraft, League of Legends, The Escapist, and IT security company FinFisher.[274] They also attacked the login servers of the multiplayer online game EVE Online, which also disabled the game's front-facing website, and the League of Legends login servers. Most of the takedowns were performed with DDoS attacks.[275]

LulzSec also hacked a variety of government-affiliated sites, such as chapter sites of InfraGard, a non-profit organization affiliated with the FBI.[276] The group leaked some of InfraGard member e-mails and a database of local users.[277] On June 13, LulzSec released the e-mails and passwords of a number of users of senate.gov, the website of the U.S. Senate.[278] On June 15, LulzSec launched an attack on cia.gov, the public website of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, taking the website offline for several hours with a distributed denial-of-service attack.[279] On December 2, an offshoot of LulzSec calling itself LulzSec Portugal attacked several sites related to the government of Portugal. The websites for the Bank of Portugal, the Assembly of the Republic, and the Ministry of Economy, Innovation and Development all became unavailable for a few hours.[280]

On June 26, 2011, the core LulzSec group announced it had reached the end of its "50 days of lulz" and was ceasing operations.[281] Sabu, however, had already been secretly arrested on June 7 and then released to work as an FBI informant. His cooperation led to the arrests of Ryan Cleary, James Jeffery, and others.[282] Tflow was arrested on July 19, 2011,[283] Topiary was arrested on July 27,[284] and Kayla was arrested on March 6, 2012.[285] Topiary, Kayla, Tflow, and Cleary pleaded guilty in April 2013 and were scheduled to be sentenced in May 2013.[286] In April 2013, Australian police arrested the alleged LulzSec leader Aush0k, but subsequent prosecutions failed to establish police claims.[287][288]

AntiSec

Beginning in June 2011, hackers from Anonymous and LulzSec collaborated on a series of cyber attacks known as "Operation AntiSec". On June 23, in retaliation for the passage of the immigration enforcement bill Arizona SB 1070, LulzSec released a cache of documents from the Arizona Department of Public Safety, including the personal information and home addresses of many law enforcement officers.[289] On June 22, LulzSec Brazil took down the websites of the Government of Brazil and the President of Brazil.[290][291] Later data dumps included the names, addresses, phone numbers, Internet passwords, and Social Security numbers of police officers in Arizona,[292] Missouri,[293] and Alabama.[294] AntiSec members also stole police officer credit card information to make donations to various causes.[295]

On July 18, LulzSec hacked into and vandalized the website of British newspaper The Sun in response to a phone-hacking scandal.[296][297] Other targets of AntiSec actions have included FBI contractor ManTech International,[298] computer security firm Vanguard Defense Industries,[299] and defense contractor Booz Allen Hamilton, releasing 90,000 military e-mail accounts and their passwords from the latter.[300]

In December 2011, AntiSec member "sup_g" (alleged by the U.S. government to be Jeremy Hammond) and others hacked Stratfor, a U.S.-based intelligence company, vandalizing its web page and publishing 30,000 credit card numbers from its databases.[301] AntiSec later released millions of the company's e-mails to Wikileaks.[302]

See also

- Memetic persona

- Composition

- Activism

- Other related articles

References

Notes

- ^ Topiary was later revealed to be Jake Davis, a teenager living in the Shetland Islands of Scotland.[71]

- ^ A portmanteau of "hacking" and "activism"

Citations

- ^ "Gabriella Coleman on Anonymous". Brian Lehrer Live. February 9, 2011. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2011 – via Vimeo.

- ^ Landers, Chris (April 2, 2008). "Serious Business: Anonymous Takes On Scientology (and Doesn't Afraid of Anything)". Baltimore City Paper. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ Oltsik, Jon (December 3, 2013). "Edward Snowden Beyond Data Security". Network World. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ Winkie, Luke (February 11, 2015). "The Ballad of Rog and Tyrone". The Verge. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Waites, Rosie (October 20, 2011). "V for Vendetta masks: Who". BBC News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: Why Anonymous 'hacked' the SABC, Gupta websites". Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ Krupnick, Matt (August 15, 2011). "Freedom fighters or vandals? No consensus on Anonymous". Oakland Tribune. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Carter, Adam (March 15, 2013). "From Anonymous to shuttered websites, the evolution of online protest". CBC News. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ a b Coleman, Gabriella (April 6, 2011). "Anonymous: From the Lulz to Collective Action". Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Rawlinson, Kevin; Peachey, Paul (April 13, 2012). "Hackers step up war on security services". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Gellman, Barton (April 18, 2012). "The 100 Most Influential People In The World". Time. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012.

- ^ Gilbert, David (November 2, 2016). "Is Anonymous over?". VICE. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Griffin, Andrew (August 7, 2018). "Anonymous promises to uncover the truth behind 'QAnon' conspiracy theory". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 7, 2022.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (June 1, 2020). "'Anonymous' is back and is supporting the Black Lives Matter protests". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ Molloy, David; Tidy, Joe (June 1, 2020). "The return of the Anonymous hacker collective". BBC. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ "The philosophy of Anonymous". Harry Halpin. February 2014. p. 27. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Kelly 2012, p. 1678.

- ^ Coleman, Gabriella (December 10, 2010). "What It's Like to Participate in Anonymous' Actions". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ a b Kelly 2012, p. 1682.

- ^ "Anonymous: what is the hacker collective?". IONOS Digitalguide. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 92.

- ^ Brown, Jesse (February 7, 2008). "Community Organization with Digital Tools: The face of Anonymous". MediaShift Idea Lab: Reinventing Community News for the Digital Age. PBS. Archived from the original on February 11, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. x.

- ^ Kelly 2012, p. 1679.

- ^ Cadwalladr, Carole (September 8, 2012). "Anonymous: behind the masks of the cyber insurgents". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ a b Allnut, Luke (June 8, 2012). "Parmy Olson On Anonymous: 'A Growing Phenomenon That We Don't Yet Understand'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Morris, Adam (April 30, 2013). "Julian Assange: The Internet threatens civilization". Salon. Archived from the original on May 4, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Kelly 2012, p. 1680.

- ^ a b c Norton, Quinn (June 13, 2012). "In Flawed, Epic Anonymous Book, the Abyss Gazes Back". Wired. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 122–23.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 355.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 356.

- ^ Munro, Alistair (June 26, 2012). "Scots hacker admits breaking into the CIA". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Verona man admits role in attack on Church of Scientology's websites". The Star-Ledger. November 16, 2009. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 89.

- ^ Albanesius, Chloe (June 13, 2011). "Turkey Arrests 32 'Anonymous' Members & Opinion". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ "Detienen en Turquía a 32 presuntos miembros de 'Anonymous' – Noticias de Europa – Mundo" [32 alleged members of 'Anonymous' arrested in Turkey – News from Europe – Mundo]. Eltiempo.Com. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Elinor Mills (September 23, 2011). "Alleged 'Commander X' Anonymous hacker pleads not guilty". CNET. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Nate Anderson (December 11, 2012). "Anon on the run: How Commander X jumped bail and fled to Canada". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Gallagher, Ryan (March 20, 2013). "How Barrett Brown went from Anonymous's PR to federal target". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Anonymous attacks PayPal in 'Operation Avenge Assange'". The Register. December 6, 2010. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ "UK police arrest WikiLeaks backers for cyber attacks". Reuters. January 27, 2011. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ "Police arrest 'hackers' in US, UK, Netherlands". BBC. July 19, 2011. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (July 19, 2011). "Fourteen Anonymous Hackers Arrested For "Operation Avenge Assange," LulzSec Leader Claims He's Not Affected – Forbes". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ "'Anonymous' hackers arrested in US sweep". Herald Sun. Australia. July 20, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ "16 Suspected 'Anonymous' Hackers Arrested In Nationwide Sweep". Fox News Channel. April 7, 2010. Archived from the original on July 29, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Halliday, Josh (January 24, 2013). "Anonymous hackers jailed for cyber attacks". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Leyden, John (December 14, 2012). "UK cops: How we sniffed out convicted AnonOps admin 'Nerdo'". The Register. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 309–310.

- ^ "National Security Agency calls hacktivist group 'Anonymous' a threat to national security". Public Radio International. February 27, 2012. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Goldman, David (January 20, 2012). "Hacker group Anonymous is a nuisance, not a threat". CNN. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "2013 Threats Predictions" (PDF). McAfee. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Leyden, John (October 24, 2011). "Anonymous shuts down hidden child abuse hub". The Register. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ Wood, Molly (January 19, 2012). "Anonymous goes nuclear; everybody loses?". CNET. Archived from the original on October 25, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (January 21, 2012). "SOPA: Feds go after Megaupload as Congress reviews anti-piracy bills". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on January 23, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- ^ Kelion, Leo (January 20, 2012). "Hackers retaliate over Megaupload website shutdown". BBC News. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ a b Norton, Quinn (November 8, 2011). "Anonymous 101: Introduction to the Lulz". Wired. Archived from the original on April 5, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Walters, Helen (June 27, 2012). "Peeking behind the curtain at Anonymous: Gabriella Coleman at TEDGlobal 2012". TED. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Caneppele, Stefano; Calderoni, Francesco (October 30, 2013). Organized Crime, Corruption and Crime Prevention. Springer. p. 235. ISBN 978-3-319-01839-3. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ "The Creator of 'Mr. Robot' Explains Its Hacktivist and Cult Roots". Motherboard. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Zetter, Kim (July 8, 2015). "Mr. Robot Is the Best Hacking Show Yet—But It's Not Perfect". Wired. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "Elementary: "We Are Everyone"". The A.V. Club. October 11, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Shuman, Phil (July 26, 2007). "FOX 11 Investigates: 'Anonymous'". MyFOX Los Angeles. KTTV (Fox). Archived from the original on May 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Beran, Dale (August 11, 2020). "The Return of Anonymous". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Whipple, Tom (June 20, 2008). "Scientology: the Anonymous protesters". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 48.

- ^ "Two-year term for Shetland hacker". The Herald. May 17, 2013. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b Dibbell, Julian (September 21, 2009), "The Assclown Offensive: How to Enrage the Church of Scientology", Wired, archived from the original on December 7, 2009, retrieved November 27, 2009

- ^ Dibbell, Julian (July 1, 2008), "Sympathy for the Griefer: MOOrape, Lulz Cubes, and Other Lessons From the First 2 Decades of Online Sociopathy", GLS Conference 4.0, Madison, Wisconsin: Games, Learning and Society Group, archived from the original on July 14, 2011, retrieved November 7, 2008 Project Chanology "mention" begins approximately 27:45 minutes into the presentation.

- ^ Popkin, Helen A.S. (April 18, 2011). "Notorious NSFW website cleans up its act". Digital Life on MSNBC. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ Everything Anonymous Archived May 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. AnonNews.org (April 20, 2013). Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ Leavitt, Alex (April 1, 2011). "Archiving Internet Subculture: Encyclopedia Dramatica". Web Ecology Project. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Stryker, Cole (2011). Epic Win for Anonymous: How 4chan's Army Conquered the Web. New York City: Overlook Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-59020-738-3. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "UK hacking suspect Ryan Cleary held after bail breach". BBC News. April 2, 2012. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Cruise bio hits stores as video clip of actor praising Scientology makes it way to Internet". The Washington Post. Associated Press. January 15, 2008. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Tucker, Neely (January 18, 2008). "Tom Cruise's Scary Movie; In Church Promo, the Scientologist Is Hard to Suppress". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 63–65.

- ^ "Fair game; Scientology". The Economist. February 2, 2008. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 71–72, 122, 124, 126–29.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 206.

- ^ Norton, Quinn (December 30, 2011). "Anonymous 101 Part Deux: Morals Triumph Over Lulz". Wired. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b George-Cosh, David (January 25, 2008). "Online group declares war on Scientology". National Post. Archived from the original on January 28, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ "Scientology faces wave of cyber attacks". Cape Times. March 4, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Curcio, James (January 15, 2020). MASKS: Bowie and Artists of Artifice. Intellect Books Limited. ISBN 9781789381092. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ Kidd, Dustin (May 15, 2018). Social Media Freaks: Digital Identity in the Network Society. Routledge. ISBN 9780429976919. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 82–3.

- ^ DeSio, John (May 6, 2008). "Queens Anonymous Member Gets a Letter from Scientologists". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Ramadge, Andrew (March 20, 2008). "Scientology site gets a facelift after protests". news.com.au. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Howarth, Mark (June 1, 2008). "Anger as police ban placards branding Scientology a cult". Sunday Herald. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 85.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 93–94.

- ^ a b Olson 2012, p. 102.

- ^ "Activists target recording industry websites". BBC News. September 20, 2010. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 103.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 104.

- ^ Tsotsis, Alexia (September 19, 2010). "RIAA Goes Offline, Joins MPAA As Latest Victim Of Successful DDoS Attacks". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on April 5, 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 105.

- ^ Williams, Chris (September 22, 2010). "Piracy threats lawyer mocks 4chan DDoS attack". The Register. Archived from the original on January 24, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Winterford, Brett (September 28, 2010). "Operation Payback directs DDoS attack at AFACT". iTnews. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Leydon, John (October 4, 2010). "Ministry of Sound floored by Anonymous". The Register. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Leyden, John (October 7, 2010). "Spanish entertainment industry feels wrath of Anonymous". The Register. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ^ Sandoval, Greg (November 9, 2010). "FBI probes 4chan's 'Anonymous' DDoS attacks". CNET. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Corrons, Luis (September 17, 2010). "4chan Users Organize Surgical Strike Against MPAA". Pandalabs Security. Archived from the original on June 18, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ "Anonymous hacktivists say Wikileaks war to continue". BBC News. December 9, 2010. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 110–11.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 115–18.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (May 31, 2012). "The Secret Lives of Dangerous Hackers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 117–19.

- ^ Addley, Esther; Halliday, Josh (December 8, 2012). "WikiLeaks supporters disrupt Visa and MasterCard sites in 'Operation Payback'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 178.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 122, 129.

- ^ Steven Musil (December 8, 2013). "Anonymous hackers plead guilty to 2010 PayPal cyberattack". CNET. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 141–45.

- ^ a b Ryan, Yasmine (May 19, 2011). "Anonymous and the Arab uprisings". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on April 9, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 148.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 10–24.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 200.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 161, 164.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 164.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 176–77.

- ^ Honan, Mat. "Cosmo the God Hijacks Twitter Account of Hateful 'Church'". Wired. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Olson 2012, pp. 178–88.

- ^ "Anonymous vows to 'destroy' Westboro Baptist Church over Sandy Hook picket plans". The Raw Story. December 17, 2012. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Uganda prime minister hacked 'over gay rights'". BBC News. August 16, 2012. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Sony caught up in cyber war with indignant hackers; Company with security once considered 'robust' now dealing with constant breaches". Associated Press. May 30, 2011. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Moyer, Edward. "Anonymous touts its own social network: 'Anon+'". CNET. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "Anonymous Is Working On AnonPlus, a Facebook For Hackers and Non-Hackers Alike". Gizmodo. July 18, 2011. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "Hackers Hacked the Hackers' AnonPlus Social Network". Gizmodo. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "BART website hacked, customer info leaked". San Francisco Chronicle. August 14, 2011. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ Malik, Shiv (May 1, 2012). "Occupy movement takes over parts of London Stock Exchange". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Hackers take down child pornography sites". BBC News. October 24, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ Liebowitz, Matt (May 15, 2012). "Anonymous Attacks Suspected Pedophiles Again". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Anonymous Targets Pedophiles Via #OpPedoChat Campaign". PC Magazine. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Steadman, Ian. "Anonymous launches #OpPedoChat, targets paedophiles". WIRED UK. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Plumlee, Rick (December 2, 2013). "Wis. truck driver given 2 years probation for cyberattack on Koch Industries | Wichita Eagle". Kansas.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Norton, Quinn. "Anonymous Tricks Bystanders Into Attacking Justice Department". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Sottek, T. C. (April 5, 2012). "Anonymous hacks Chinese government sites in protest, some still compromised". The Verge. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "BBC News – Chinese websites 'defaced in Anonymous attack'". BBC. April 5, 2012. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ Protalinski, Emil. "Anonymous hacks hundreds of Chinese government sites". ZDNet. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ Roy, Jessica (December 4, 2012). "Anonymous Hunts Revenge Porn Purveyor Hunter Moore". Betabeat. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Chan, Casey (November 16, 2012). "Anonymous Targets Israel by Taking Down Hundreds of Websites and Leaking Emails and Passwords". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Kershner, Isabel (April 7, 2013). "Israel Says It Repelled Most Attacks on Its Web Sites by Pro-Palestinian Hackers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Gonsalves, Antone (May 3, 2013). "Experts hope for another failure in next Anonymous attack". CSO Online. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Messmer, Ellen (May 5, 2013). "Anonymous cyberattack on Israel finds disputed impact". Computerworld. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Protesters gather around the world for Million Mask March". The Guardian. November 5, 2013. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ "#OpSafeWinter: Anonymous fights homelessness worldwide". The Daily Dot. January 4, 2014. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "OSW Flyer 1 | OpSafeWinter". Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Forum Post: #Anon #OpSafeWinter Call to Action & New York #D26 Assembly - OccupyWallSt.org". Occupy Solidarity Network. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "T'is the Reason for the Season – #OpSafeWinter". Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "#OpSafeWinter: Generosity Goes Viral". The Interdependence Project. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c Bever, Lindsey (August 13, 2014). "Amid Ferguson protests, hacker collective Anonymous wages cyberwar". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Hunn, David (August 13, 2014). "How computer hackers changed the Ferguson protests". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on May 31, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Harkinson, Josh (August 13, 2014). "Anonymous' "Op Ferguson" Says It Will ID the Officer Who Killed Michael Brown". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Bosman, Julie; Shear, Michael D.; Williams, Timothy (August 14, 2014). "Obama Calls for Open Inquiry Into Police Shooting of Teenager in Ferguson, Mo". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Anonymous Releases Alleged Name Of Officer They Say Fatally Shot Michael Brown". KMOX News Radio 1120. August 14, 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Pagliery, Jose (August 14, 2014). "Ferguson police deny Anonymous' ID of alleged shooter". CNN Money. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Hunn, David. "Twitter suspends Anonymous account : News". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Jamie Bartlett (November 19, 2014). "Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous by Gabriella Coleman – review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Boroff, David (November 24, 2014). "Grieving dad, Anonymous lash out at Cleveland cops following shooting death of boy, 12, armed with BB gun". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ Danylko, Ryllie (November 26, 2014). "Anonymous begins looking into past of Timothy Loehmann, cop who fatally shot Tamir Rice". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ "'Hacktivist' group Anonymous says it would avenge Charlie Hebdo attacks by shutting down jihadist websites". The Telegraph. January 9, 2015. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015.

- ^ "Anonymous declares war over Charlie Hebdo attack". CNN Money. January 9, 2015. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ Newsbeat (January 12, 2015). "Hackers Anonymous 'disable extremist website'". BBC. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Newsbeat (January 9, 2015). "Anonymous hackers 'declare war' on jihadists after France attacks". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Fekete, Jason (June 17, 2015). "Government of Canada websites under attack, hacker groupAnonymous claims responsibility". National Post. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2015.