Charles Henry Allan Bennett

Charles Henry Allan Bennett | |

|---|---|

Ordained as a Bhikkhu Ananda Metteyya | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 8 December 1872 London, United Kingdom |

| Died | 9 March 1923 (aged 50) |

| Resting place | Unmarked grave buried in Morden Cemetery, South London, England |

| Notable work(s) | The Religion of Burma and Other Papers,[1] & The Wisdom of the Aryas.[2] |

| Occupation |

|

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Theravada |

| Monastic name | Ananda Metteyya (also early version: Ananda Maitreya) |

Charles Henry Allan Bennett (8 December 1872 – 9 March 1923) was an English Buddhist and former member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. He was an early friend and influential teacher of occultist Aleister Crowley.[3][4][5]

Bennett received the name Bhikkhu Ananda Metteyya at his ordination as a Buddhist monk and spent years studying and practising Buddhism in the East. He was the second Englishman to be ordained as a Buddhist monk (Bhikkhu) of the Theravāda tradition[6] and was instrumental in introducing Buddhism in England. He established the first Buddhist Mission in the United Kingdom and sought to spread the light of Dhamma to the West. Co-founder of international Buddhist organisations and publications, he was an influential Buddhist advocate of the early 20th century.

Early life

[edit]Allan Bennett was born in London on 8 December 1872, [7][8] his full name at birth was Charles Henry Allan Bennett. His only sister, Charlotte Louise was born in Brighton about a year before.[9] His childhood was difficult and filled with suffering. His father died when he was still a boy, and his mother struggled to support the family, who nevertheless raised him as a strict Roman Catholic. [10][11][12][13] During his youth he was plagued with bouts of acute asthma, which were debilitating even for weeks at a time.[9][14]

According to Crowley, he had early experiences of an "unseen world". As a young boy, about the age of 8, he overheard some gossip among superstitious servants, that if you recite the "Lord's Prayer" backwards, the Devil would appear. Bennett went into the back garden to perform the invocation and something happened which frightened him. [15][13] At sixteen he was disgusted at a discussion of childbirth,[10] becoming furious he stated, "children were brought to earth by angels". After being confronted with a manual of obstetrics, accepting the facts, he said: "Did the Omnipotent God whom he had been taught to worship devise so revolting and degrading a method of perpetuating the species? Then this God must be a devil, delighting in loathsomeness." At this moment he lost his belief in God and relinquished his faith[15][9] announcing himself an 'agnostic'.[16][17] In his personal biographical notes on Bennett, Crowley once stated "Allan never knew joy; he disdained and distrusted pleasure from the womb."[18]

Bennett's father had been a civil and electrical engineer, [19][7][14][13] following in his footsteps Bennett was a keen natural scientist. Bennett was educated at The Colonial College at Hollesey Bay, Suffolk, and later at Bath, England,[19][9][17][20] with keen interest in Chemistry and Physics.[21] Upon leaving school, he trained as an analytical chemist[7][20] and achieved some success in that field. Bennett also conducted his own experiments, while no inventions or patents were fruitful at the time.[22] Possibly true, in a fictional work Crowley depicts Bennett as working on one process "trying to make rubies from ruby dust" also stating a precisely similar process was in commercial use by others only years later.[23] Bennett was eventually employed by Bernard Dyer,[20] a London-based public analyst and consulting chemist with an international reputation. Dyer was also an official analyst to the London Corn Trade[24] and invited Bennett to participate in an expedition to Africa. Bennett in the end turned down the offer to go, and stated to an occultist colleague and friend Frederick Leigh Gardner that he was rather glad for this because he could focus on furthering his esoteric practices.[25][26] It is said that Bennett was Bernard Dyer's most promising student, though his shocking health prevented him from holding a job.[25][26][12] Bennett also inquired of Gardner, if he could obtain a teaching position in chemistry or electrical science at local day schools.[9] His electrical knowledge was profound, extending into the "higher branches of Electricity, Hertz waves, Röntgen rays, etc.":[17] this and his talent for experimental science, mathematics and physics would stay with him throughout his life.[27] Cassius Pereira mentions that Bennett had "done much electrical work, which was just coming to fruition, when his health broke down...". [8]

Bennett's constant sickness created a heavy lens of suffering towards life. He was disenchanted towards the illusions of pleasure and love and saw these as the hidden enemy of mankind binding each being to the curse of existence. [15][14]

Search for spiritual truth

[edit]

Having left Catholicism in his teens, Bennett was still in search to fill the void that had formed from this parting as he ever wished to find his place in the spiritual spectrum.[14] Having a heart and intellect that sought cause and effect, analytical knowledge and wisdom, he wanted to apply scientific analysis to religion and uncover true spiritual gnosis. When Bennett was eighteen he fell in love with Sir Edwin Arnolds' book The Light of Asia (1879), which at the time was said to cause "an enormous upsurge in awareness of, and interest in, Buddhism".[16][28][3] This was a real turning point in Bennett's life, and made a revolutionary impression that lasted his lifetime.[29][30][31][14] He was so deeply moved by the pure and rational faith experienced through Arnold's poetry. This religious experience lead the way for Bennett to develop a closer association with the existing English translations of Buddhist Scriptures.[31][16] Thus at this tender age of eighteen, having been inspired by The Light of Asia, Bennett announced himself a Buddhist by Faith. [32][16][8]

Biographer Elizabeth J. Harris states Bennett "was a man of his time, born when the British Empire was at the height of its power and the wish to probe new religious pathways was gripping many young minds." [33] Bennett searching for the height of Ultimate Truth, sought to find spiritual realization through the doors of religious and mystical practices and teachings available to him. One notable experience that occurred, also at the age of eighteen, where all at once Bennett spontaneously attained to the cosmic yogic state of annihilation Shivadarshana,[25][13] literally meaning "to have sight of Siva."[13] Even though he was immediately thrown out, Crowley comments it was "a marvel that Allan survived". Even after years of hard practice the effect on him was transformative, he said to himself referring to that lofty state: "This is the only thing worthwhile, I will do nothing else in all my life but find out how to get back to it."[34] Crowley further noted "It is a marvel that Allan survived and kept his reason," as this extraordinarily high state of yogic attainment can be dangerous, a potential cause for madness.[35] Crowley further explained the cross reference that Shivadarshana is the same experience as one of the formless arupa jhana's in Buddhism. [36]

On 24 March 1893, Bennett applied to join the Theosophical Society.[9][12] This society was a known path to spiritual exploration covering mystical traditions from east to west; yoga, religion and the esoteric and exoteric were all seen as things to be studied and practised. Notable also that the founders both had declared themselves as Buddhist in Ceylon in 1880.

Shortly before his 21st birthday in November 1893, Bennett wrote a letter to F. L. Gardner stating "I have been ill - had an attack of apoplexy, which laid the body up..." going on to request a set of astrological Ephemerides so he could track back a horoscope of his exact time of birth.[37] During his time Bennett also gave a lecture to the Lodge on Egyptian mythology. By 1895 Bennett had lost interest in the Theosophical Society and turned his full attention to the esoteric gnosis. [9][38]

Golden Dawn

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn |

|---|

|

Dawn of the esoteric

[edit]Bennett was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1894,[39] taking the Latin motto "Voco", ("I Invoke").[40] He quickly progressed through the grades, entering the Second Order as a 5=6 on 22 March 1895 and taking the Hebrew motto "Iehi Aour", ("let there be light").[40][41][42][5] He was always very poor and tormented by illness, but still made a strong impression on other occultists of the time.[43] Bennett was one of the most luminous minds in the order[44][45][31][14] and favoured mysticism and white magic rather than the occult. [3][46] Bennett was almost wholly concerned with divine knowledge and enlightenment rather than siddhis (magical powers) seeing them as mundane and divorced from the unrealised but glimpsed heights of spiritual attainment.[36][46][25]

After initiation into the Second Order of the Golden Dawn on 22 March 1895, Bennett was considered the most proficient second only to S. L. Mathers and attained extraordinary success.[15][43][47] Bennett had high regard for Golden Dawn leader Mathers, so much so it is said that he was adopted by Mathers and took his last name on until Mathers' death.[19] Notably he also helped Mathers put together an extended work the Book of Correspondences, a systematic grouping of esoteric symbols and numbers from around the world which Crowley later expanded into a book of Hermetic Qabalah: Liber 777.[44][48]

Bennett at the age of twenty-three was already working on his own occult formula, which was seen as quite astonishing, one such popularised account was the esoteric ceremony he wrote for Golden Dawn associate and actress Florence Farr.[49][50][51] The ceremony was rather difficult and detailed, drawing on antiquity, involved things like the Egyptian symbol of immortality, and harmonising the forces of Mercury with Mercury's intelligence Tiriel, while working in the hour of Tafrac under the domain of the Great Angel of Mercury.[49][50] Its purpose is stated to learn the hidden mysteries of art and science.[49] With the second order of the Golden Dawn having over thirty members,[52] in a period that was exceedingly orthodox,[53] it is no wonder that his association with the occult haunted Bennett in later life.[54] During this period Bennett was fascinated with the arithmetical subtleties of the literal Qabalah, and via his essay Liber Israfel we can note his poetic musing incorporating Egyptian symbology specifically on the 20th Major Arcana of Tarot, Judgement.[55] Crowley recounts a humorous magical tale before their first encounter, where Bennett had created a consecrated talisman of the Moon to cause rain. To make it work it needed to be immersed in water. Bennett had somehow dropped it and "it worked its way into the sewer, London proceeded to have the wettest summer in the memory of man!"[56]

Crowley had been in the same order as Bennett for over a year, however their first encounter was in early 1899 on the initiation of a new member into the order. During the ceremony Crowley became aware of a "tremendous spiritual and magical force" coming from the east; he knew it must be Frater Iehi Aour.[57][58] After the ceremony Crowley was "led trembling before the great man" though he could not bring himself to say a word. In the anteroom an hour after the ceremony, Bennett came directly to Crowley startling him by announcing "Little brother, you have been meddling with the Goetia!" Crowley withholding the truth in shock denied this, Bennett replied: "then Goetia has been meddling with you." Bennett it seems could sense that Crowley had been "dabbling in malignant forces beyond his control". [59][57][60][61][62] Crowley went home somewhat reprimanded and determined to call on Bennett the next day.[58][57][63] Crowley later recounted "He had spotted me as a promising colt, and when, using my opportunity, I made myself even as his familiar spirit, he consented to take me as a pupil. Before long we were working together day and night, and a devil of a time we had!"[64]

George Cecil Jones and Bennett were known to be Crowley's primary teachers during his days in the Golden Dawn. Bennett, four years older than Crowley, was the more experienced of the two and continued on to be one of greatest influences and inspirations in Crowley's life. [60][65][44][66] The only other person that Crowley places on such an upper tier with Bennett is Oscar Eckenstein stating his "moral code was higher and nobler than that of any other man I have met."[67] Crowley found in Bennett a Teacher of spiritual gnosis and a friend in spiritual seeking, and found him to be an "inspiration to work in white magic",[46] further imparting "he bequeathed to me a beautiful Garden, the like of which hath rarely been seen upon Earth."[68]

Poverty, chronic sickness, and accessing mysteries

[edit]Soon after the meeting, Crowley was shocked to find that Bennett was living in a dilapidated apartment in the slums south of the Thames with another Brother of the Order. Crowley, deeply impressed with the man also pitying his situation, invited Bennett to come stay with him, now enabling the two light seekers to work together more fluently.[57] Crowley organised a room for him in his Chancery Lane flat, "and settled down to pick his brains", for he knew his reputation "as the one magician who could really do big-time stuff".[25] For days, weeks and months, Bennett trained Crowley in the basics of magic[69] and tried to instill a devotion to white magic.[70] Bennett was generally ascetic and reputedly sexually chaste, a marked contrast to Crowley's libertine attitude.[71] In a fictional work Crowley depicts Bennett's disposition towards chastity stating "He had an aversion to all such matters amounting to horror."[23] Even though all early sources point to Bennett's chastity, unfounded rumours seem to of circulated in later years in an attempt to smear Crowley. Israel Regardie, who was a personal secretary of Crowley's for a time, agrees the rumours seem to be baseless, that he never heard anything from Crowley or any substantiated claim to suggest otherwise.[72][60][73] Crowley had said of him "We called him the White Knight", that there "never walked a whiter man on earth" that he was a harmless, lovable "terribly frustrated genius".[25]

In the preface introduction to Iehi Aour's work "A Note on Genesis" Crowley states "Its venerable author was an adept" with the esoteric system of symbols, accomplished in harmonising them in himself (here referring to what would later be known as Liber 777).[74] "In the year 1899 he was graciously pleased to receive me as his pupil, and, living in his house, I studied daily under his guidance the Holy Qabalah."[68] Crowley goes on to praise the "ratiocinative methods employed", and that the methods utilised were indeed "so fine and subtle that they readily sublime into the Intuitive."[74] As to some darker occult experiments that Crowley dabbled in at Chancery Lane he made the clear and specific point that Bennett "never had anything to do with this".[75]

Crowley described Allan as tall, though "his sickness had already produced a stoop. His head, crowned with a shock of wild black hair, was intensely noble; the brows, both wide and lofty, overhung indomitable piercing eyes. The face would have been handsome had it not been for the haggardness and pallour due to his almost continuous suffering."[15][76] He went on to describe how in spite of Bennett's ill-health "he was a tremendous worker". That he has a vast, precise and profound understanding of science and electricity.[15][77] Crowley noted "He showed me how to get knowledge, how to criticise it and how to apply it."[78] Also highlighting how Bennett had immersed himself in Buddhist and Hindu teachings for the purpose of spiritual insight. Crowley continued to relate that he "did not fully realize the colossal stature of that sacred spirit" and yet he was at once aware that "this man could teach me more in a month than anyone else in five years."[15][51]

At a time when there was no legal prohibition against drugs, Bennett was an experimental user of available drugs (with which he also treated recurrent asthma) and introduced Crowley to this aspect of his occult and alchemical researches.[79][71][15][80] Furthermore, as a part of his experiments into accessing the mysteries of the "subconscious and super-normal mind" and "the World behind the Veil of Matter" it is alleged he even experimented with poisons once taking an overdose that would have otherwise killed another man, though he remained unharmed.[31][71][60][46][3] While Bennett was soon to abandon the practice of such experimentation and uses, Crowley went on to a life of hedonistic addiction though always held Bennett in the highest regard.[81][82]

Crowley also painted a grim picture of how Bennett suffered acutely from spasmodic asthma at that early time. Bennett would take one drug at a time (up to a month) until it was no longer helping then cycled through the other drugs available to him until he was reduced to using chloroform.[46][15] Crowley recalled how even for a week he would see him "only recovering consciousness sufficiently to reach for the bottle and sponge". After a brief period of being well the asthma would return again, and Bennett would be once again forced back into this grim cycle of existence.[15][71] Crowley stated, "But through it all the calm undaunted spirit walked the empyrean, and the radiant angelic temper ripened the wheat of friendship."[25]

Impact, influence, and change of view

[edit]

In a hallowing scene Bennett is described as "calm, majestic, clearly master of it all", Crowley paints in detail the aura of the man, that thunders forth; "instantly a ray of divine brilliance cleaves the black clouds above his head, and his noble countenance flashing in that ecstasy of brightness."[83] Crowley stating how this picture of Bennett was the literal truth. That Bennett was one of the very few people that he had met "who really could get ... the results they wished for" in this esoteric field, for it is easy for most to get unwished for results "madness, death, marriage".[83]

Biographer Kaczynski states that Crowley took on the Adeptus Minor Grade motto, "let there be light" in Enochian; a translation of Bennett's Hebrew motto Iehi Aour. This shows a clear reference to the influence of his teacher and friend.[84] Crowley once remarked concerning Bennett's powers: Bennett had constructed a magical wand out of glass, a lustre from a chandelier which he carried with him. [85][86] He preferred this to the wands recommended by the G.D. and would keep it "charged with his considerable psychic force and ready for use".[87] As it so happened, Crowley and Bennett were at a party and a group of theosophists present were ridiculing in disbelief the power of the wands. It was alleged by Crowley that "Allan promptly produced his and blasted one of them. It took fourteen hours to restore the incredulous individual to the use of his mind and his muscles."[85][15][86][88]

Crowley states how he had hoped Bennett would establish the Order in Asia "The Dawn was Golden when you met the guide, ... You took the boat that floated with the tide, To leave behind no track... I hoped that you would raise my magic Sword, Upon another strand."[89] One of the differences they faced was that Crowley seemed to think that virtuous conduct could be bypassed, where Bennett went as far to insist it was the first founding factor an aspirant required, seeing the deficiencies in the West, namely the blamelessness of keeping the precepts. [90][91] Crowley's Autobiography is dedicated to three "Immortal Memories", including "Allan Bennett, who did what he could".[92] Sutin states that Crowley tried to rekindle the connection, Bennett was the reluctant one and eventually the two of them did start to drift apart. [93]

Crowley notes years later "Allan, strangely enough it seems to me, lost interest rather than gained it as we acquired proficiency in the White Art... He didn't really care for Magic at all; he thought that it led nowhere. He only cared for yoga."[94][95][51] Also while Bennett was a strong influence on Crowley's early life and later thought,[96] Bennett one day responded to Crowley "No Buddhist would consider it worthwhile to pass from the crystalline clearness of his own religion to this involved obscurity."[97] Years later Crowley's reprinted Bennett's essay "On the Culture of Mind", likely without his knowledge, with the new name "Training of the Mind" in the Equinox series. Here it can be seen that their understanding of ultimate reality had taken separate roads, Crowley seemed to think the two paths compatible, while Bennett was unwavering in his religious zeal.[90][98] On a sombre note, Kaczynski quotes what Crowley wrote down upon his friends' departure, now aware of Bennett's change in path: "O Man of Sorrows: brother unto Grief!"... "In the white shrine of thy white spirit's reign, Thou man of Sorrows: O, beyond belief!".[99]

Travel to Southeast Asia

[edit]Ceylon, yoga and Buddhism

[edit]At some time between 1889 and 1900, in his late twenties, Bennett traveled to Asia[100][101][102] to relieve his chronic asthma, after submersing himself in the study Buddhism.[16][32] He traveled to Ceylon as a self-converted Buddhist, staying at Kamburugamuwa in the Matara district for four months, Bennett studied the Pali language and the root Theravadan Teachings under an elder Sinhala monk Venerable Revata Thera.[17][3] Cassius Pereira later recalled that "such was the brilliance of his intellect" that he had mastered that ancient tongue in six months and could fluently converse."[103][104] Further that Bennett "made many close friends amongst the Buddhists of Ceylon, who gave him much assistance in every way."[104] Bennett also spent time visiting monasteries, monks and sacred sites, familiarising and immersing himself with the Buddhist culture and practice of Ceylon. [31]

In Colombo he studied Hatha Yoga under the yogi Ponnambalam Ramanathan (Shri Parananda) who was said to be a man of "profound religious knowledge".[105][31][106] As Bennett's health improved, he served as tutor to the younger sons of the Shri Parananda, who was a high-caste Tamil and the Solicitor General of Ceylon.[105][107] Florence Farr a prior Golden Dawn associate, was also to move over to Ceylon years later, and became the principal lady of Shri Parananda's College for Girls.[108] Bennett joined the Sangha under the yogi and took the name Swami Maitrananda,[109] which was already of Buddhist significance. The psychic potency of the man become more pronounced as he mastered the breathing techniques, mantras, asana postures and concentration practices in an amazingly short time period. [31][106][3] Crowley visited Bennett in Kandy, and personally attended on him during a yogic meditation retreat.[110] Crowley supported his retreat by quietly bringing food into the room nextdoor to where Bennett was practising. Having missed two meals in a row, Crowley out of concern checked on Bennett finding him not seated on the central mat, but at the end of the room still in the Padmasana yoga posture "in his knotted position, resting on his head and right shoulder, exactly like an image overturned." Crowley set him a right, and he came out of the trance quite unaware that anything unusual had happened. [110][111]

With his health improving in the warm weather, he was now free from the chronic cycle of drugs he had needed in England.[112] Also, he had relinquished his experimentation into psychic and esoteric power.[113] Bennett's quest for spiritual meaning had finally been quenched as he began to commit to the practice and Teachings of Theravada Buddhism.[113] Crowley noted Bennett was "the noblest and gentlest soul I have ever known", and in spite of his teacher & friend's prior experimentation that "Allan was already at heart a Buddhist". [114][115] Egil Asprem states "Following Bennett's example Crowley also engaged in a more intimate relation with Buddhism during his visit [116] and would subsequently consider himself a Buddhist for many years".[117] Bennett later recounts "The native, and correct, designation of the pure form of Buddhism now prevalent in Burma, Ceylon, and Siam is Theravādha, 'The Tradition of the Elders' or, as we might justly render it, the Traditional, Original, or Orthodox School."[118] His intellect, spiritual endeavour and faith sees this school as the "pure and simple" ... "practically unchanged after twenty-five centuries", that its inheritance is not mythical but rather "the actual words" the Buddha employed on his "religious mission" that are still rolling down to the present.[119]

In July 1901, Bennett gave a talk at the Theosophical Society in Colombo named the "Four Noble Truths". Attending this talk was the young Cassius Pereira who was so deeply moved at this talk, it changed his life, and he became a lifelong friend of Bennett and later also took up the robes.[120][17][102] Bennett, at this time decided he would lead a Buddhist Mission to England.[16][121] To do this he realised it must be carried out by a Bhikkhu of the Buddha's Sangha, thus seeing the limitations in Ceylon he set his vision on Higher Ordination in the Theravada Buddhist Order of monks in Burma.[16][122][51] He had come to the see that the path of renunciation, was the only path for him, the more he studied and practised the more he was attracted to it.

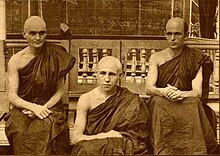

Out of darkness into the light

[edit]Bennett travelled to the coastal city of Akyab at took up residence at the Buddhist monastery, the Lamma Sayadaw Kyoung. Bennett was accepted into the Order by Lamrna Saradaw as a Samanera (novice monk) on 8 December 1901. [123][17][122][124] During this time he spent his time learning and improving further his knowledge of Pali, learning the duties of a Buddhist Monk and writing Buddhist papers for a publication Ceylon.[17] Half a year later, on Vesak Day the Full Moon May 1902, a long line of seventy-four Buddhist monks proceed from Kyarook Kyoung towards the wharf edge for the new Samanera's Higher Ordination. The ceremony was taken place on the water, presided by Sheve Bya Sayadaw, and it is here that he moved from the ten precepts of a novice to the 227 precepts of a Buddhist Bhikkhu.[125][17][32] Still unacquainted with the Burmese tongue, Shwe Zedi Saradaw translated each sentence into English, likely the first occurrence of this happening in history.[17] His ordination name was Ananda Maitreya, a Sanskrit name,[17][102] soon to be changed to the Pali rendition Ananda Metteyya to be inline with the Theravada roots, which means "Bliss of loving kindness".[105][126][3][127][102] Ananda was also the name of Gautama Buddha's attendant, and the Sanskrit Maitreya and the Pali Metteyya are the name of the coming Buddha stated in the suttas.[128][129] With fresh vigour he addressed the Sangha at this auspicious ceremony, outlining how he intended to help spread Buddhism to the West.[130] He spoke of the conflicts that were forming due to the clash of science and religion, and spoke of a vision of bringing to the West that shining faith and Path of the Buddha that he had first truly experienced in Ceylon. Crow quotes him as stating "Herein, then, lies the work that is before me", that his purpose is to "carry to the Lands of the West the Law of Love and Truth" declared by the Buddha, to establish a Sangha of Bhikkhus in his name.[130][16][131] Metteyya filled with zeal closes the speech with: "bringing from the East even unto the West, the splendour of a Dawn beyond our deepest conception; bringing joy from sorrow, and out of Darkness, LIGHT."[17]

Metteyya was the second known Englishman to be ordained as a Bhikkhu, after Gordon Douglas who was ordained in Ceylon 1899.[126][132] During Metteyya's ordination speech he made an earnest call to "countrymen ... who will come to the East, and receive the requisite Ordination, and acquire a thorough knowledge of the Dharma" to help teach the West, "this work I have already commenced on a small scale."[17] Harris states Metteyya made a "call for five men from four countries to come to Burma to be trained for higher ordination."[133] One such German man, who may have heard this call, travelled to find Metteyya and soon ordained as a novice, staying on with Metteyya for a month. The sāmaṇera then went to Kyundaw monastery, which was nearby boarding the forest, and in February 1904 was accepted into the Sangha as Ñāṇatiloka Bhikkhu, the first known continental European to receive higher ordination. He was later grateful for meeting the supporters of Metteyya and made use at one point of the hut that had been built for Metteyya.[134] Harris holds a letter from 10 February 1905, were Metteyya is commending Ñāṇatiloka asking Cassius Perera if he would help him further stating "he is an easily-contented mortal, with a very gentle and considerate nature".[135] Ñāṇatiloka went on to become the father of western monks in Ceylon.[136]

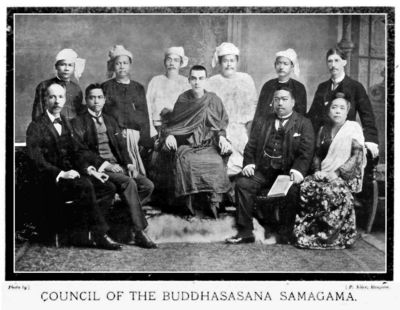

Brotherly bonds of all mankind

[edit]In Rangoon 1903, Metteyya and Ernest Reinhold Rost co-founded the International Buddhist Society known as Buddhasāsana Samāgama. It was an "international Buddhist society that aimed at the global networking of Buddhists."[125][3][127][137][138] Its motto was "Sabbadānaṁ dhammadānaṁ jināti" meaning "The Gift of Truth Excels All Gifts" taken from the Dhammapada v. 354.[139] Metteyya was Secretary General and made Edwin Arnold, the man who was the first to illuminate the Buddhas Path to him with the Light of Asia, the first honorary member of the Society. [140][141] Harris goes on to state that "Buddhasāsana Samāgama gained official representatives in Austria, Burma, Ceylon, China, Germany, Italy, America, and England." Enthusiasm and greetings began to pour in from all around the world. [137][142] His friend Cassius Pereira (who later entered the Sangha, becoming Bhikkhu Kassapa in 1947 at the Vajiraramaya Temple) referring to this period recalls that Metteyya gave several "inspiring addresses from the Maitriya Hall". Pereira's Father built Maitriya Hall at Lauries Road, Bambalapitiya in honour of Ānanda Metteyya,[143] its related group 'Servants of the Buddha' has been active down to the 21st century. [144]

The Buddhasāsana Samāgama garnered an immediate interest, with three hundred attendees at a Conversazione in Rangoon, a few months after its inception.[145] In September 1903, whilst still in Rangoon, Metteyya began a periodical called Buddhism: An Illustrated Review. Metteyya was instrumental in its production and appears in the prospectus with Dr. Ross as secretary-general.[137] The Quarterly Review was really the heart pulse of the society, which was sent to all Members without additional cost and "sold to the General Public at three shillings a copy".[146] However, funding was difficult and further the work was often delayed due to Metteyya's sickness. Metteyya avidly contributed to each addition, for example some of his first works were In the Shadow of Shwe Dagon,[147][148][149] "Nibbāṇa",[150] "Transmigration"[151] & "The Law of Righteousness".[152] Buddhasāsana Samāgama also notably printed its constitution and rules in Volume 1 Issue 2.[153][127]

During this time Albert Edmunds helped to promote the journal, he too openly hoped for a synthesis between the east and the west.[154] Edmunds acceptance of the position of America representative to the Society, was more humanitarian "I have taken this Rangoon representativeship so as to be useful and justify my existence." Further explaining "I am not a Buddhist, but a philosopher who believes that a knowledge of Buddhism will liberalize Christianity ..." Tweed further explaining Edmund's rationale "it seemed to be capable of broadening Christianity and fusing cultures."[155] So Edmunds became the person of note in North America and at the same time Anagarika Dharmapala and one J. F. McKechnie became inspired after reading Metteyya's article 'Nibbana'.[154][156][136] McKechnie stated "It seemed to me couched in a fine style of English and moderate, rational, clear and convincing in its argument", he was inspired and moved, saying "It hit me where I lived".[156] McKechnie soon answered and appeal and became sub-editor of the journal, and within some years had himself left to Burma to become Bhikkhu Sīlācāra.[154][156]

While fitful due to Metteyya's illness, the Illustrated Review was considered a success.[156] Thought pioneer James Allen (author of As a Man Thinketh), Rhys Davis, Shwe Zan Aung,[157] Paul Carus, J. F. M'Kechnie, Cassius Pereira[158] and Maung Khin (barrister from Rangoon whom was later a Chief Justice of the High Court) are some of the contributing authors in the first few publications. Mrs. Hla Oung who was the sponsor of Metteyya hut in Ceylon, who was daughter of the late Sitkegyi Oo Tawlay, wife of Oo Hla Oung (Controller of the Indian Treasuries), also appears in the first issue in an article entitled "The Women of Burma".[159][160][161][162]

Due to said distributions there were only six issues of Buddhism printed between 1903 and 1908. Harris details the principles underlining the missionary and international vision outlined in the first issue. One, "to set before the world the true principles of our Religion" to give rise to "wide-spread acceptance among the peoples of the West" its true practice as a vehicle to promote general happiness. Two and three set to encourage wholehearted humanitarian activities and to further those interested in ever growing numbers to unite under common brotherly bonds of all mankind in alignment with True Buddhist ideals.[163]

By December 2003, Volume 1 Issue 2 stated "Some five hundred copies of our first number were sent gratuitously[164] to the Press, Libraries, Universities and other institutions in the West" so that the real work of spreading the light to the West was well underway.[165] Metteyya continued to maintain a high level of international contact and by 1904, thanks to the generous supporters in Burma, the periodical was appearing on the reading table of 500 to 600 libraries across Europe.[133][166] Christmas Humphreys states that the first issue appeared in September 1903, and the "production and quality of contents" was "the most remarkable Buddhist publication in English which has yet appeared", that ramifications of this and the ensuing five issues was immense.[7]

Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland

[edit]R. J. Jackson,[167] who with the help of a fellow friend and Buddhist R. J. Pain[168] founded 'The Buddhist Society of England'.[169][170] With the help of Ernest Reinhold Rost[171] the three of them set up a bookshop at 14 Bury Street, Bloomsbury, close to the British Museum, and would promote the Societies cause by placing Buddhist literature for sale in store front window to encourage interest.[122][172][173][174] Rost actively lectured in private congregations and the group soon started to garner support.[7][122] A portable platform was painted in luminous orange bearing the words "The Word of the Glorious Buddha is sure and everlasting" and used in parks for lectures also gathering a considerable audience.[122][173] Humphreys referring to Jackson also states "In 1906 the first English practising Buddhist began to lecture on Buddhism from the traditional soap box in Hyde Park."[169]

Francis Payne mentions on his way to the British Museum he noticed the Buddhist leaning bookshop.[137] Furious he went in and stated, "Why are you bringing this superstition to England?". One of them asked him not to be in a hurry and suggested he read one of the books, presenting him with "Lotus Blossoms",[175] by Bhikkhu Sīlacāra. Soon after Payne was himself giving Dhamma lectures and became an integral part of the Society.[122] It is said that Francis Payne went on to be the greatest Buddhist evangelist of the era second only to Metteyya.[176]

Jackson and Pain soon got in touch with Metteyya, and preparations began to pave the way for his arrival,[174] the time was now ripe for Metteyya's vision to be fulfilled.[169] On the evening of 3 November 1907, a meeting commenced at Harley Street, London. Some twenty-five people had attended, the result of this meeting 'The Buddhist Society of England' was expanded[170][174] to form 'The Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland', which based its structure on its Rangoon counterpart.[7][177][178] Christmas Humphreys later said its main purpose was "to welcome and serve as the vehicle for the teachings"[179] of Buddhism to the West.

With its formation the King of Thailand became Patron[170] and the eminent Pali scholar Professor Rhys Davis accepted the position of President. Professor Edmund T. Mills, F.R.S., Captain J. E. Ellam also took on key roles on the committee. This newly formed team of five was given the task "of drawing up a provisional Prospectus, Constitution and Rules, and the convening of another and larger meeting". [7][180][178]

A few names of such eminent Buddhist followers were Captain Rolleston, Hon. Eric Collier, sculptor St George Lane Fox-Pitt, painter Alexander Fisher, The Earl of Maxborough[181] & A.J. Mills.[7][122][182] Hermann Oldenberg, Loftus Hare[183] (who went on to be a part of the Parliament of Living Religions), Sir Charles Eliot, C. Jinarajadasa, D.T. Suzuki and Mme David-Neel are further notable names of those who supported or contributed to the Society.[184]

Bennett was associated with the Society, when health was able, throughout the rest of his life. Bennett was also a key editor of their periodical, The Buddhist Review which was founded in 1909 and ended in 1922.[154][185] It was certainly challenging, partly composed of the religiously inspired, true converts, scholars, scientists, sceptics, agnostics and those who had to work hard to keep the Society afloat.[186] Its headquarters in London, was seen as the oldest Buddhist organisation in Europe. Officially the Society was would up in 1925 and superseded by the Buddhist Lodge in London, in 1926. By 1953 it was known as the Buddhist Society and had relocated to its current address in Eccleston Square. Notably its journals have been Buddhism and The Middle Way and Christmas Humphreys was its president from 1926 until his death 1983.[187][188]

First Buddhist mission to England

[edit]With the recent dawn of "The Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland" Ananda Metteyya arrived on the steamship Ava with three devoted lay supporters at Albert Dock on the shores of England, in the United Kingdom, on 22 April 1908.[189][190][178][191] Soon after stepping off the ship, Metteyya was questioned as to his purpose for coming to England, he replied "in order to set forward the principles of Buddha in this country" also elucidating that Buddhism blends harmoniously with other creeds, giving one clear example: "its position as regards Christianity is that it supplements."[192]

This was the first true Buddhist Mission to the West, the first lecture was soon to take place in London before the Royal Asiatic Society on 8 May. [132][191][192][193] While circumstances were difficult, and public opinion was resistant at times, [100][189][192] Metteyya's personal charisma meant that he garnered "golden opinions and the friendship and respect of all who had the privilege of meeting him."[194] A historical account in the "Voice of Buddhism" relates that Metteyya "began his work with great enthusiasm" and that "people came in large numbers to his Dhamma talks and meditation classes."[170] Fifty years later Christmas Humphreys recalls that Metteyya "brought Buddhism as a living force to England" that it was the start of a slow growing movement of "many to live the Buddhist life".[100]

Christmas Humphreys also recounts his meeting of Metteyya on this inaugural Mission, in London 1908: with head shaven, the "then thirty-six years of age" Bhikkhu was "tall, slim, graceful, and dignified." Humphreys describes Metteyya's deep-set eyes juxtaposed against a slightly ascetic appearance, that surely Metteyya "made a great impression on all who met him". The young monk was well-spoken, interesting with conversation and topic, with a pleasant voice, "and in his lighter moments he showed a delightful sense of humour". Metteyya displayed a "deep comprehension of the Dhamma" and his wit of analogy by topic of science and his sheer "power and range of thought combined to form a most exceptional personality." [27][195]

One magazine printed part of Metteyya's writing in May 1908, "Buddhism, ... with its central tenet of non-individualisation, is capable of offering to the West, to England, an escape from this curse of Individualism", recounting this a root to suffering. Ending he encourages the temperament of Burma to Londoners "one learns to respect not wealth but charity, and to revere not arrogance but piety."[196] There were many newspaper articles published in Britain and some abroad, mostly positive.[197]

During this period the influential and prolific populariser of Zen Buddhism, Japanese writer and academic Suzuki Daisetsu Teitarō, met with Metteyya. Suzuki is later noted for his strong influence on such people as Edward Conze, Alan Watts & Christmas Humphreys, further expanding interest in Eastern Buddhism.[198]

While in London Metteyya was active in giving a number of lectures including one entitled "Buddhism" at the Theosophical Society, 10 June 1908. By September, he was meeting with members of the Buddhist Society every Sunday.[178] All Metteyya's industry and devotion to the cause, helped grow the Society's membership considerably. Many of Metteyya lectures later appeared as pamphlets, in the Society's journal or in The Buddhist Review.[178] Metteyya and his devoted lay supporters, concluded the inaugural mission, leaving London to Liverpool on 29 September 1908, then travelling by way of ship back to Burma.[178]

Christian missionary Rev. E. G. Stevenson studied Buddhism in Burma during this period and subsequently took up the yellow robes. The newly ordained Venerable Sasanadhaja went on to help Metteyya with his missionary work. Also in 1909, 'The Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland' expanded its membership base to three hundred. [182]

Teachings and declining health

[edit]Rescuing force of truth

[edit]

In a biographical account Harris reveals that Metteyya had pity and compassion for the hearts of the West. He noted the signs of great neglect in our culture such as "crowded taverns", overflowing jails and "sad asylums".[199][200] To cope with this loss of religious and moral awareness he had laid down a three-fold agenda as a remedy. First to address this loss of moral awareness, so as to encourage the "spirit of mutual helpfulness" rather than the current curses faced by society due to such degradation. Second, he opposed three misconception about Buddhism: that it was uncivilised worship of idols, that it was "miracle-mongering and esotericism" and that it was a spineless, "apathetic, pessimistic manner of philosophy". Third he had introduced his impression of Buddhism; as rational, optimistic, and that the Buddha was certainly a remarkable and enlightened Teacher.[199]

Metteyya had highlighted the spiritual poverty of the West through his dedicated writing, with Theravada Buddhism presented as the force that could rescue it.[201] Metteyya would give a range of teachings during this time encouraging others to see the benefit of virtue in precepts, with its opposing suffering,[202] establishing faith in the Buddha as a foundation and even to develop the ability to recall past lives.[203][204] The purpose for his teachings was to inspire but also to use these things to see into the suffering of existence and understand the Four Noble Truths as to personally attaint to the far shore, the goal of the Theravada Buddhist Teachings. With a simile of the force of required in by high-pressure steam in a steam locomotive, Metteyya encourages the aspirant to use the right skillful means of meditation to allow the mind not to flow out into the world, but to intensify the power of the mind in one spot, based on purity.[205] He makes statements like "Aspiration, Speech, Action, and so forth stand for consecutive stages in the path of spiritual progress" inclining his audience towards the higher fruitions.[206] He found light in the teaching that "whatsoever phenomenon arises, it is invariably an effect produced by an antecedent cause" giving rise to a profound understanding of the three characteristics.[207][208] Metteyya goes on to use a comparative simile of what enlightenment is, then states it is the destruction of the illusion of self, the unbinding of the five Khanda's of existence. That when that truth of liberation is reached it is "Illimitable, the Element of Nirvana" reigns supreme.[209]

Buddha's message to the West

[edit]On the 89th anniversary of the 'United Kingdom Buddhist Day' on 16 July 1997, Tilak S. Fernando related the life, successes and struggles of Metteyya.[210][211] He states that after returning to Rangoon, Metteyya was highly satisfied with the spiritual success of the mission though his health had steadily declined and the financial support for the mission was exhausted. While the Metteyya had found the Teachings were not broadly accepted with great enthusiasm, he was once again determined to push on to further the transmission of this Light.[210] In December 1908 Metteyya wrote an "Open Letter to the Buddhists of England" earnestly appealing those interested in the Teachings to support the prosperity of the Society. At this time the Society had already swollen to one hundred and fifty members, and with all the graceful eloquence and inspiration he could muster, he posed the glory of the Buddha's message as the answer to the immediate needs of the West.[210] Fernando goes on to state Metteyya's "iron will to return to England was still alive, though the effort necessary to carry on with even routine work was terrible." [212]

To his further impact on the growth of Buddhism, Metteyya is referenced in organising the Western Wing of the International Buddhist Union, a group started by Anagārika Dharmapāla which later formed into the World Fellowship of Buddhists in 1950.[213] Metteyya was also commended for his work in Burma encouraging Buddhism to be taught in schools.[214][200] It is also suggested by Harris that the anti-Buddhist pressure in Ceylon had caused Metteyya to dedicate his time helping "to equip Buddhist children to withstand the arguments of the Christian missionaries."[215] This being a possible reason also for the waning possibility of a return mission to England.

Murmurs and inmost shrine of Buddhism

[edit]Crowley set to praise his old guru and published a newspaper article on 13 June 1908, stirring images of the brilliance of his old friend and teacher. First painting the surreal graphic details of ceremonial magic then going on to state "How wonderful must then be the inmost shrine of Buddhism, when we find this same Allan Bennett discarding as childish folly the power of healing the sick, or raising the dead, of the attainment of the Philosopger's Stone, the Red Tincture, the Elixir of Life!".[83] Metteyya clearly having renounced his prior esoteric path to take up the "white heights" of spiritual Buddhist practice.[83] "What strange attraction must lie" in the yellow robes of a Bhikkhu, "the Begging Bowl, the shaven head, and the averted eye". Crowley goes on to rouse Londoners to a monumental illustration that this man has "torn the heart of Truth bleeding from the dead body of the universe", that they who are hungry should seek his wisdom. That to all serious men who seek for real Faith, that this man has "passed through all the ways of life and dead" and he is attained, "Latin Intra Nobis Regnum:[216] Bhikkhu Ananda Metteyya - Allan Bennett - is the man to help you find it."[83] Crowley's arousal of energy, probably purely motivated, was likely a key factor in Metteyya's later character assassination attacks. Certainly his former life as an occultist and public admiration from Crowley would have added to the hype of murmurs and baseless accusations.[217][73]

Dark suspicion over Metteyya's controversial past and associations seem to captivated some part of the public. While his faith and practice was genuine, Metteyya still was a controversial figurehead. Both due to his history in the esoteric and his ongoing contact with friends in groups such as the Theosophy Society, meant the suspicion continued.[218] In years to come these rumours were to amplify when Crowley was openly attacked in the media. This resulted in the names of both Jones and Metteyya to be dragged through the mud. Jones tried to sue the journal for libel which resulted in a drawn out court case.[219][220][221] One news article said of Metteyya: "the rascally sham Buddhist monk Allan Bennett, whose imposture was shown up in Truth some years ago" is likely one of the worst examples of the accusations thrown about. "Counsel proceeded to question the witness with regard to Allan Bennett, a Buddhist monk, and also a member of the Order, and it was at this point" that his lordship Mr. Justice Scrutton remarked "this trial is getting very much like the trial in ‘Alice in Wonderland,’".[220][221]

No facts were certified in the trial, evidence was presented in a way that Metteyya was associated with the occult and libertine lifestyle of Crowley. This unfortunate public perception may indeed be one of a handful of causes in Metteyya's waning ability for to spread the Dhamma through a further mission. The power of these stories and insinuations, really a form of character assassination, can be seen as some have even rippled down to the 21st century.[217][73][222]

Metteyya had the full support of his close friends in Buddhist circles, Harris remarks that its worthy of attention several articles were run in his lifetime to help state he had given up his past and "was not a man of 'mystery'".[223] One editorial stating "There is no more mystery attending the Bhikkhu Ānanda Metteyya than any other person", Clifford Bax likewise stating from first glance the genuine nature of the man.[224]

Remembering backwards

[edit]Metteyya in his early teachings and throughout his life prompted those he knew and taught to invoke a meditation practice that would enable the aspirant, firstly to remember backwards and ultimately to recall their past lives.[225][page needed][2][226] Being one of the psychic powers used for realisation in Buddhism, he taught it as a tool to see that the continuation of rebirth in saṃsāra is suffering, enabling the aspirant to sharpen ones insight to perfect right view.[225][page needed][227][228][229]

Alec Robertson, president and longstanding member of Servants of the Buddha[230][231][232] the society that has run at the Maitriya Hall (Colombo, Sri Lanka), that was built in Ananda Metteyya's memory,[230][232] recalled that in a conversation with Metteyya's close friend Cassius Pereira alleged having such a close connection with Metteyya "that the two could communicate by telepathy", that each could know the others thoughts even at great distance.[231][232] Biographers Crow & Sutin also dive into the topic of Crowley's struggling efforts following his old teacher and friends advice.[233][234] Wild as it may seem to the modern skeptic, knowledge of past lives is described as one of the psychic powers that the Buddha realized on the night of his enlightenment.[235]

Digestible Dhamma and deterioration of health

[edit]Metteyya realised that the best path for Dhamma to arise in the West was through the Sangha of Bhikkhus, that this was the primary and indispensable foundation for the Buddha's Truth taking root in a society.[236] This honest realisation was stated in 1910, further in this letter Metteyya announced "I do not think that the maintenance of a single Bhikkhu, whether myself or another, would, as things now are, at all conduce to that end. Quite the contrary, in fact." [236] Here Metteyya was referring to the difficulties of establishing a Sangha of Bhikkhus that could flourish, while strictly adhering to the Vinaya.

Metteyya instead set forth the idea of the creation of Dhamma Literature that was constructed in a way that was easily digestible, broken into shorter fragments to be more suited to the modern disgruntled mind.[236] "The Dhamma, best for the deeper student in actual translations, is too archaic for the modern average man to start on. It needs interpreting into ways of thought, rather than translating into verbal likeness."[236]

Metteyya's earlier plans to establish a permanent Buddhist community in the West, in England,[237] waned under his new understanding that Ven. Sīlācāra or himself would be unable to properly establish a Sangha in the West.[236] This marked the end of Metteyya's time as a dedicated Buddhist Missionary to England.[238][239] Metteyya had stated that one who lives his true vocation of this life as a Bhikkhu, must follow the Vinaya accordingly to prove himself against temptations as a religious teacher amongst his fellow-men, to be wise and worthy so that he be a living example through the actions of his life.[240] While Metteyya's determination to return was great, his health was rapidly declining.[241][242][239] Metteyya further stated "I should be very sorry indeed to see the first beginnings of Buddhist monasticism in England founded on a deliberate and a continuous breach of the rule by which the Bhikkhu should live".[243]

Speaking of the heart of Dhamma in this letter Metteyya states "Now at this point I must pause to emphasise that our Dhamma, our Sasana, is the Truth about life, the Religion which comes as the Crown, as the Goal, of all religious teaching which has ever been given to the world."[244] That we have learnt the "fundamental movements" necessary to follow what is "Right and Truth" superseding our "mental baby-hood" becoming "self-reliant", endowed with "personal responsibility" taking up the mantle of the "great pilgrimage of Life".[245] Quoting the Buddha Metteyya writes "Seek ye therefore Refuge in the Truth; looking on yourself and on the Truth as Guides, not seeking any other Refuge."[246]

In 1909 Bennett's early Qabalistic work A Note on Genesis appears in Crowley's The Equinox, Volume I, Number II.[68] In 1911 Metteyya's Buddhist work The Training of the Mind appears in The Equinox, Volume I, Number V.[247] Also in 1911, Metteyya publishes his a collection of his Buddhist articles: An outline of Buddhism; or, Religion of Burma. The latter was published in Rangoon, Burma, through the International Buddhist Society with an introduction by the Theosophical Society,[248] later republished posthumously in 1929.[1]

Burma's climate was aggravating Metteyya's asthma, and the austerity of the rules of a Bhikkhu was causing him to be weak.[178] While the dates were not stated, Cassius Pereira mentions that he had gallstone trouble, had two operations and his chronic asthma had returned.[241][249] Crowley states "his life as a bhikkhu had not been too good for my guru" his physical health was in a "very shocking state" including "a number of tropical complaints".[242] Metteyya's doctors had reluctantly given him the advice to leave the Order of Monks "where he had now attained the seniority of a Thera or Elder."[250] In 1913 he had conversed with his sister, they decided it would be best if he moved to California so the better climate could aid in his recovery. In May 1914, Ananda Metteyya disrobed, no longer a Buddhist Monk, and with the aid of some local friends left Burma to return to England.[178][251][169][239][51]

Return to England and final years

[edit]Arriving in England on 12 September 1914, Bennett met his sister who was to accompany him on the journey to America.[252][178] Unfortunately due to his failing health the US ship medic denied his immigration visa. His sister sailed without him, and he found himself stranded, forced to live in poverty and illness in England.[252][51] Bennett, now a layperson, was once again incapacitated with chronic asthma for weeks at a time and with the outbreak of World War I his situation was looking dire.[177]

Though Bennett's situation was bleak, all was not lost. A doctor and his family who were a member of the Liverpool branch of the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland took him in for two years, though the strain was too great.[239][178][51] An anonymous group of well-wishers ensured that Bennett was taken care of through support of the Buddhist Society, to save him from being placed in public care. As the help came in, from local and abroad, Bennett's health improved.[253][51]

The Wisdom of the Aryas

[edit]With refreshed vigour, in winter of 1917–1918, Bennett gave a series of six private lectures in Clifford Bax's studio.[239] With war raging, Bennett still roused his listeners to the sublime "Nirvana stands for the Ultimate, the Beyond, and the Goal of Life", describing that our transient conditioned selfhood was so utterly different to what was truly "beyond all naming and describing, but far past even Thought itself."[254] Also encouraging householders to bring the "ever-present sun-light of the Teachings" into their daily lives.[255] In May 1918, Bennett aroused the members of the Buddhist Society to fresh enthusiasm in what Christmas Humphreys described as a "fighting speech".[256][178]

Humphreys later cites Metteyya in his classic Buddhism:

Life's long enduring suffering has arisen out of the blind Nescience ... with the sense of separate existence, are states of suffering.[257]

Harris cites one account that mentions Bennett, though sick for weeks at a time, took over the editorship of the Buddhist Review in 1920, January 1922, being the final edition.[239][258] The title, Arya meaning "Noble" in Sanskrit (likewise Āriya in Pali), refers to those who have attained to the Buddhas path of the four stages of enlightenment.[259][260][261] Bennett then took the lectures he had given at Clifford Bax's studio and used them as the main basis of his book The Wisdom of the Aryas,[2] published January 1923. Included was one teaching on transmigration "one of the most difficult of Buddhist Teachings to make clear to the western mind."[178][262]

Bennett dedicates the work The Wisdom of the Aryas to his dear friend Clifford Bax, who hosted the lectures which were the basis for the bulk of the compilation. Bennett states: during the early "terrible years of the Great War, I came to London, broken in health and despairing of further possibility of work for the cause to which my life has been devoted". This is the "first-fruits of my work as published in a western land", thanking Bax for making "possible the resumption of my life-work" with heartfelt gratitude signed Ananda Metteyya.[263]

Death

[edit]Clifford Bax recounts his meeting of Bennett in 1918: "His face was the most significant that I had ever seen" that one could both sense the twisting and scoring from years of physical suffering, and a "lifetime of meditation upon universal love" these gave rise to the most remarkable impression. "Above all, at the moment of meeting", Bennett emanated a tender shimmering unwavering "psychic sunlight" that was a halo to his persona.[264]

It was clear by early March 1922 that Allan Bennett was deteriorating rapidly. The suffering was plain even for others to see. Charles Alwis Hewavitharana[265] and in all likelihood Cassius Pereira continued to support Bennett in his final days at 90 Eccles Road, Clapham Junction, London.[266][267] Allan Bennett died on his native English soil at the age of 50, on 9 March 1923.[178][251][268] Hewavitarana cabled the necessary funds for his grave in Morden Cemetery in South London.[266][258] Christmas Humphreys recalls the event:

flowers and incense were placed on the grave by members of the large gathering assembled[266]

Lifelong friend and Buddhist writer, Cassius Pereira, wrote:

... on the 9th of March, in London, the Buddhist world loses one of its foremost protagonists of late years.[8]

And now the worker has, for this life, laid aside his burdens. One feels more glad than otherwise, for he was tired; his broken body could no longer keep pace with his soaring mind. The work he began, that of introducing Buddhism to the West, he pushed with enthusiastic vigour in pamphlet, journal and lecture, all masterly, all stimulating thought, all in his own inimitably graceful style. And the results are not disappointing to those who know.[250]

Paul Brunton, in 1941, shared that Allan Bennett had "stimulated me spiritually and quickened my dawning determination to decipher the profound enigma of life". Brunton recounts his respect and honour for Bennett, leaving us with his thanks for:

this white Buddhist whose ship has sailed for the infinite waters of Nirvana.[31]

Tilak S. Fernando on 'United Kingdom Buddhist Day' in 1997 ends his speech paying homage to Venerable Ananda Metteyya's legacy:

And so, there passed from sight a man whose memory would honour for bringing to England, as a living faith, the message of the All-Enlightened One[268][269]

Legacy

[edit]Allan Bennett was a pioneer, and without him, Buddhism would not have entered the Western world as it did.[270][100] In particular he encouraged and introduced the "serious study of Buddhism as a spiritual practice" into Britain, and further fostered its growth in Burma and Ceylon.[271][272] Just before Bennetts death in 1923 the collection of lectures that had taken place in Clifford Bax's studio[273][239] plus and addition paper on Rebirth were printed in the book The Wisdom of the Aryas.[2][239] Posthumously in 1929 the Theosophical Publishing House in India printed The Religion of Burma and Other Papers a collection of Metteyya's writings from the first decade of the century a rework of the 1911 release.[239][248] This latter collection subsists of the bulk of articles that have been published throughout his life as a Buddhist Monk, and as a devoted Buddhist. "Rightly indeed have the Buddhists of the East decided that these inspiring writings shall not be consigned to the oblivion which overtakes back-numbers of journals, but made accessible to the world in the form of a volume."[274] Many of his addresses and papers are still intact, available and in use today.[275]

Ananda Metteyya is remembered for his promotion of Buddhist education in Burma and his central role as a figure promoting the global networking of Buddhism[276] including the first true authentic roots of the Buddha's Sangha in the West.[133][277] Known both as a critic of the moral stagnation of the West and as a keen promoter of the beliefs of the East at the dawn of the 20th century.[133] Metteyya was noted as one of the few early Western Buddhists who possessed reason, devotion and a strong grip of the Buddhist truths. Metteyya played an important role as one of these prolific forerunners "who opened the eyes of their generation to an ancient wisdom long lost to the Western world".[278]

Reiterated in the posthumous release 'The Religion of Burma'[1] the introduction states:

For the whole of the powers of this remarkable man were devoted to one single object - to the exposition of the Dhamma in such a manner that it could be assimilated by the peoples of the West.

Metteyya was also noted "by virtue of the literary skill" to engage and share Buddhist thought through "vivid expression ... the knowledge" he had realised.[278] "One can hardly turn a page of his prose essays without coming across some passage which is instinct with ... imaginative expression".[21] Metteyya's passion for the Buddha's Teachings as a way of life, his ingenuity and industry in bring that Light to the West, his example as a keen practitioner of Dhamma, all of this helped kindle a sense of spiritual urgency and seeking in those who crossed his path and teachings. His life work in summary was to share with the West the Noble Eightfold Path, the Majjhima-Pātipadā: that place of practice that avoids both extremes and leads to enlightenment, the total extinguishment of all suffering.

If … any of you shall be able to gain even some faint glimmer of the Buddhist Religion and its incomparable value to the western world, it will be my very great reward; and, as you in such case will surely find, your very great advantage.[279]

Our western world… I believe will find, the greatest answer to its questionings, the simplest presentations of the deepest facts about life, in this same wonderful Teaching of the Indian Prince, who sought and found alone the Way to put an End to Suffering – the Way to Everlasting Peace.[279]

Tricycle Magazine also quotes Metteyya's thoughts on the Buddha's teachings: [280]

All that remains to us is Action … He taught, but action true, following to the best of our small powers; … make a man our Master's Follower

...wherefore by earnestness work out your Liberation[280]

Works

[edit]- Bennett, Allan (1923). The Wisdom of the Aryas. London & New York: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. / E. P. Dutton & Co.

- Bennett, Allan (1929). The Religion of Burma and other Papers. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House.

- As editor

- York University Digital Library | Buddhism: An Illustrated Quarterly - Vol. 1, No. 1

- York University Digital Library | Buddhism: An Illustrated Quarterly - Vol. 1, No. 2

- York University Digital Library | Buddhism: An Illustrated Quarterly - Vol. 1, No. 3

- York University Digital Library | Buddhism: An Illustrated Quarterly - Vol. 1, No. 4

- York University Digital Library | Buddhism: An Illustrated Quarterly - Vol. 2, No. 1

- The Buddhist Review, Volume 1, Number 2

- The Buddhist Review, Volume 11, Number 3

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c Bennett 1929.

- ^ a b c d Bennett 1923.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Melton 2000, p. 169.

- ^ Kaczynski & Wasserman 2009, Chp. 6 Crowley credited... "his focus on concentration and awareness practices to the influence of his two early mentors, Oscar Eckenstein and Allan Bennett.".

- ^ a b Crow 2008c, p. 1.

- ^ Batchelor 1994, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Humphreys 1956, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d Bennett 1929, p. 432. The Late Mr Allan Bennett by Cassius Pereira.

- ^ a b c d e f g Crow 2008a, pp. 14–36.

- ^ a b Regardie 1986, p. 41.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 149 cites Symonds & Grant 1989: 180.

- ^ a b c Harris 2013, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e Crowley, Beta & Kaczynski 1998, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris 2006, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Crowley 1989, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Humphreys 1956, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Metteyya 1902.

- ^ Harris 1998a, p.11 cites Confessions, p.234.

- ^ a b c Harris 1998a.

- ^ a b c Harris 2006, p. 149 cites Grant 1972: 82.

- ^ a b Bennett 1929, p. v.

- ^ Crow 2008b, pp. 30–33.

- ^ a b Leo & Crowley 1911.

- ^ Harris 1998a, cites Kenneth Grant, The Magical Revival (Frederick Muller Ltd., London, 1972), p.82n.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grant 1972, p. 87.

- ^ a b Howe 1985, p. 151.

- ^ a b Harris 1998a, Ch. 1, § 'The Mission to England', Paragraph 3. Cites Humphreys, Sixty Years of Buddhism in England, p.7.

- ^ Antes, Geertz & Warne 2004, p. 454 cites Ahnond 1988: 1.

- ^ Harris 1998a, cites The Magical Revival, p.85..

- ^ Crow 2008a, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brunton Ph.D 1941.

- ^ a b c d The Annals of Psychical Science 1908, p. 260 (Vol III No. 41).

- ^ Harris 1998a, p. 10.

- ^ Grant 1972, p. 87 cites an unpublished manuscript entitled Origins.

- ^ Harris 1998a, p.12 cites The Magical Revival, p.85..

- ^ a b Crowley 1909, § XIX.

- ^ Howe 1985, p. 105.

- ^ Harris 2013, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Harris 1998a, p. 13.

- ^ a b Gilbert 1986, p. 151.

- ^ Kaczynski 2010, p. 62.

- ^ Howe 1985, p. 296.

- ^ a b Crow 2008a, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Sutin 2000, p. 64.

- ^ Harris 1998a, Ch. 1, § 'The Search for Truth', Paragraph 2.

- ^ a b c d e Sutin 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Owen 2004, p. 191 inc. fn.12.

- ^ Crowley 1983, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Mysteries of the Unknown 1989, pp. 153–155.

- ^ a b Howe 1985, pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harris 2013, p. 82.

- ^ Howe 1985, p. 99.

- ^ Curtice, Clery & Perry 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Harris 2013, p. 80.

- ^ Colquhoun 1975, p. 147.

- ^ Crowley, Beta & Kaczynski 1998, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Symonds 1951, p. 27.

- ^ a b Crowley 1989, Ch. 20.

- ^ Owen 2004, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d Campbell 2018, Ch. 1, § 'The Dawn of the Magician'.

- ^ Colquhoun 1975, p. 146.

- ^ Crowley, Beta & Kaczynski 1998, p. 28.

- ^ Campbell 2018, Chp. 1, § 'The Dawn of the Magician'.

- ^ Grant 1972, p. 28.

- ^ Crowley 1989, p. 464.

- ^ Kaczynski & Wasserman 2009, Chp. 6 Crowley credited "his focus on concentration and awareness practices to the influence of his two early mentors, Oscar Eckenstein and Allan Bennett.".

- ^ Crowley 1989, Ch. 18, p. 159.

- ^ a b c A ∴ A ∴ Publication 1909.

- ^ Regardie 1986, p. 113.

- ^ Symonds 1951, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b c d Symonds 1951, p. 28.

- ^ Regardie 1986, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Sutin 2000, p. 212-213 cites Confessions, J. F. C. Fuller - "Introductory Essay" to Bibliotheca Crowleyana - p. 7.c. 68 & The Looking Glass, 29 October 1910.

- ^ a b Bennett 1889, § Prefatory Note.

- ^ Sutin 2000, p. 65 cites Confessions Ch.21.

- ^ Grant 1972, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Howe 1985, p. 150.

- ^ Howe 1985, p. 194.

- ^ Sutin 2000, p. 67.

- ^ Owen 2004, p. 151.

- ^ Sutin 2000, pp. 234, 266, 281, 296.

- ^ Crowley 1989, Ch. 54.

- ^ a b c d e Crowley 1908.

- ^ Kaczynski 2010, p. 72.

- ^ a b Gilbert 1983, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b Grant 1972, p. 88.

- ^ Colquhoun 1975, p. 148.

- ^ Howe 1985, p.151 cites Confessions, p.80.

- ^ Grant 1972, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Metteyya 1911, pp. 31, 57. Inc. Crowley's footnotes.

- ^ Crowley 1989, Ch. 27.

- ^ Crowley 1989, p. 27.

- ^ Sutin 2000, pp. 193–194, 389–390 cites J. F. C. Fuller - "Introductory Essay" to Keith Hogg - [666] Bibliotheca Crowleyana (catalog of Fuller's collection...) (Kent, UK: 1966), p. 5 & P. R. Stephensen and I. Regardie - Legend of Aleister Crowley (1970) - p. 70.

- ^ Crow 2008a, p. 16.

- ^ Colquhoun 1975, p. 90. Also showing his loss of interest.

- ^ Regardie 1986, pp. 112–113, 232, 236, 286, 297–298, 319.

- ^ Sutin 2000, p. 193.

- ^ Crow 2008c, p. 3.

- ^ Kaczynski 2010, Ch. 3, Golden Dawn, para. 85–86 citation "To Allan Bennett MacGregor," from The Soul of Osiris (1901), rpt. Works 1: 207. The phrase "Man of Sorrows", besides reflecting his physical state, also applies to the Buddhist trance of Dukkha.

- ^ a b c d Humphreys 1972, pp. 133–136.

- ^ Crow 2008c.

- ^ a b c d Harris 2006, p. 150.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 150, cites Pereira 1923: 6.

- ^ a b Bennett 1929, p. 434. The Late Mr Allan Bennett by Cassius Pereira.

- ^ a b c Sutin 2000, p. 90.

- ^ a b Owen 2004, p. 228 see fn. 19 cites Crowley, Confessions, 237.

- ^ Owen 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Owen 2004, pp. 227–228 cites Crowley, Confessions, 237; and Josephine Johnson, Florence Farr: Bernard Shaw's "New Woman" (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe Ltd., 1975), 93.

- ^ Golden Dawn Research Ctr 1998.

- ^ a b Crowley 1989, Ch. 29.

- ^ Kaczynski 2010, Ch. The Mountain Holds a Dagger, para 114..

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 150 cites Foot Note 4, inc. Symonds & Grant 1989: 180, James Adam 1913, A.C. Wootton 1910.

- ^ a b Harris 2006, p. 150 cites Symonds & Grant 1989: 237, 249.

- ^ Harris 1998a, Ch. 1, § 'In Siri Lanka', cites Confessions, p.237.

- ^ Wilson 2005, Chp. 3. para. 52.

- ^ Churton 2014, p. 78.

- ^ Asprem 2012, p. 87.

- ^ Bennett 1929, p. 4.

- ^ Bennett 1929, pp. 4–8.

- ^ Harris 1998a, Ch. 1, § 'In Siri Lanka', cites "Why do I renounce the World?", p.67.

- ^ Shrine & Pesala 2009, pp. 19-20 cites "Sixty Years of Buddhism" by Christmas Humphreys, page 1–5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shrine & Pesala 2009, pp. 19-20 cites "Sixty Years of Buddhism" by Christmas Humphreys, page 1-5.

- ^ Humphreys 1956, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 150 (though states December, 12).

- ^ a b Harris 2006, p. 150 cites fn 5 inc. Humphreys 1968: 3–5.

- ^ a b Buswell Jr & Lopez Jr 2014, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Humphreys 1956, p. 28.

- ^ Harris 1998b, pp. 9–10, 14, 19, 34 n.5, 53.

- ^ Robinson, Johnson & Thanissaro 1996, pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b Crow 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Shrine & Pesala 2009, pp. 19–20 cites "Sixty Years of Buddhism" by Christmas Humphreys, page 1-5.

- ^ a b Harris 1998b, p. 174.

- ^ a b c d Harris 2013, p. 78.

- ^ Hecker & Nanatusi 2008, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Harris 2013, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Harris 2013, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Shrine & Pesala 2009, pp. 19-20 cites Sixty Years of Buddhism by Christmas Humphreys, page 1-5.

- ^ Harris 2013, p. 78 states it was 1902.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903b, Prospectus after p. 528 see p. vii.

- ^ Oliver 1979, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Antes, Geertz & Warne 2004, p. 454.

- ^ Harris 2013, p. 84, speaks of the struggles and more details.

- ^ Harris 1998a, Ch. 1, § 'The Search for Truth', also see fn. 4.

- ^ Senanayake 2021.

- ^ Shrine & Pesala 2009, pp. 19-20 cites Sixty Years of Buddhism by Christmas Humphreys, page 1–5.

- ^ Humphreys 1956, pp. 28–29.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903a, pp. 100–112.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903b, pp. 267–288.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1904a, pp. 462–472.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903a, pp. 113–134.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903b, pp. 289–312.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1904a, pp. 353–379.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903b, Prospectus see p. 528 onwards.

- ^ a b c d Williams & Moriya 2010, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Tweed 2000, p. 102 cites Edmunds details of Edmunds Diaries & Papers see note 52 of tweed for more.

- ^ a b c d Humphreys 1956, p. 29.

- ^ Min 2018.

- ^ Harris 1998a, p. 84.

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903a, pp. 61–83.

- ^ The Somerset and West of England Advertiser 1908.

- ^ Wright 1910.

- ^ Hecker & Nanatusi 2008, p. 24 fn.28, Mrs. Mah May Hia Oung ... A biography of this Burmese philanthropist is found in The Buddhist Review, Vol. II, Oct-Dec, 1910, No. 4, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Harris 1998a, Ch. 1, § 'In Burma', cites Buddhism: An Illustrated Quarterly Review, Vol. 1:1, pp.63–64, see also notes 36 to 38 in Harris 1988a.

- ^ meaning here: 'costing nothing'

- ^ 'Buddhism' 1903b, p. 319.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 150 cites Editorial comment, Buddhism 1, 3 March 1904: 473..

- ^ Some of Jackson's later books include "Buddhism and God" (1940) & "India's Quest for Reality". Both were published in London by the Buddhist Society

- ^ an ex-soldier from Burma

- ^ a b c d Humphreys 1956, p. 122.

- ^ a b c d Buddhist Missionary Society 1984.

- ^ Hecker & Nanatusi 2008, p. 24 fn. 29 R. Rost (1822-1896) was for many years the head of the Indian Office Library in London, at this time was from the Indian Medical Service, on leave from Rangoon.

- ^ Humphreys 1956, p. 30.

- ^ a b Kitto 2005.

- ^ a b c Humphreys 1951, p. 224.

- ^ Silacara 1922.

- ^ Shrine & Pesala 2009, p. 21 cites Sixty Years of Buddhism, page 1-5.

- ^ a b Harris 2006, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Crow 2008b, p. 33.

- ^ Connolly 1985, pp. 3–6.

- ^ Antes, Geertz & Warne 2004, p. 454 fn. 8.

- ^ The Teesdal Mercury 1913, column 3, para. 8.

- ^ a b World Fellowship of Buddhists 1956, p. 16.

- ^ Theosophy Wiki 2017.

- ^ Shrine & Pesala 2009, p. 21 cites "Sixty Years of Buddhism", page 1-5.

- ^ Humphreys 1956, p. 132.

- ^ Shrine & Pesala 2009, pp. 16-22 cites "Sixty Years of Buddhism", page 1-5.

- ^ Oxford Reference 2011.

- ^ The Buddhist Society 2017.

- ^ a b Harris 2006, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Harris 1998a, Ch. 1, § 'The Mission to England', cites Humphreys, Sixty Years of Buddhism in England, p.7.

- ^ a b Yorkshire Telegraph and Star 1908.

- ^ a b c The Homeward Mail 1908.

- ^ Kaczynski 2010, Epilogue para. 44.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 151 cites BR, I, 1909: 3.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 151 cites Humphreys 1968: 6.

- ^ "The First Buddhist Monk in England" (PDF). T.P.'s Weekly. London: Walbrook & Co. 1 May 1908. p. 565. OCLC 5002964.

- ^ The Dundee Evening Telegraph and Post, 23 April 1908; The Straits Times Singapore, 19 May 1908, p. 5; The Maha-Bodhi and the United Buddhist Word. June 1908, pp. 88–90; The People's Journal, 20 June 1908; The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 7 September 1908, p. 6; Aberdeen Daily Journal, 29 September 1908, p. 5; The Motherwell Times, 2 October 1908.

- ^ Antes, Geertz & Warne 2004, p. 471 cites Fader 1986: 95, p. 472 cites Humphreys 1968: 78-79.

- ^ a b Harris 2006, pp. 148-149 cites Bennett 1903a: 12, 13 & 35.

- ^ a b Harris 2013, p. 88.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Metteyya 1903, pp. 353–360.

- ^ Sutin 2000, p. 163.

- ^ Metteyya 1911, pp. 28, 29, 30, 55.

- ^ Metteyya 1911, pp. 37–50.

- ^ Metteyya 1913, pp. 85–108.

- ^ Harris 1998a, Ch. 'The Path' cites Wisdom of the Aryas, p.32.

- ^ Regardie 1986, p. 42.

- ^ William 1923, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b c Fernando 1997.

- ^ Deegalle 2018, pp. 52–73 side note on purpose of the United Kingdom Buddhist Day.

- ^ Fernando 1997, para. 12.

- ^ Antes, Geertz & Warne 2004, pp. 460-461 also cites Humphreys 1968: 15.

- ^ Harris 1998a, cites Minute Book, 3 December 1909, The Buddhist Society, London.

- ^ Harris 2013, p. 86.

- ^ literally means "Inside Us the Kingdom of god"