Rectum

| Rectum | |

|---|---|

Anatomy of the human rectum | |

Scheme of digestive tract, with rectum marked | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Hindgut |

| Part of | Large intestine |

| System | Gastrointestinal system |

| Artery | Superior rectal artery (first two-thirds of rectum), middle rectal artery (last third of rectum) |

| Vein | Superior rectal veins, middle rectal veins |

| Nerve | Inferior anal nerves, inferior mesenteric ganglia[1] |

| Lymph | Inferior mesenteric lymph nodes, pararectal lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes, deep inguinal lymph nodes |

| Function | Store feces prior to defecation |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | rectum intestinum |

| MeSH | D012007 |

| TA98 | A05.7.04.001 |

| TA2 | 2998 |

| FMA | 14544 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

The rectum (pl.: rectums or recta) is the final straight portion of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals, and the gut in others. Before expulsion through the anus or cloaca, the rectum stores the feces temporarily. The adult human rectum is about 12 centimetres (4.7 in) long,[2] and begins at the rectosigmoid junction (the end of the sigmoid colon) at the level of the third sacral vertebra or the sacral promontory depending upon what definition is used.[3] Its diameter is similar to that of the sigmoid colon at its commencement, but it is dilated near its termination, forming the rectal ampulla.[4] It terminates at the level of the anorectal ring (the level of the puborectalis sling) or the dentate line, again depending upon which definition is used.[3] In humans, the rectum is followed by the anal canal, which is about 4 centimetres (1.6 in) long, before the gastrointestinal tract terminates at the anal verge. The word rectum comes from the Latin rēctum intestīnum, meaning straight intestine.

Structure

The human rectum is a part of the lower gastrointestinal tract. The rectum is a continuation of the sigmoid colon, and connects to the anus. The rectum follows the shape of the sacrum and ends in an expanded section called an ampulla where feces is stored before its release via the anal canal. An ampulla (from Latin bottle) is a cavity, or the dilated end of a duct, shaped like a Roman ampulla.[5] The rectum joins with the sigmoid colon at the level of S3, and joins with the anal canal as it passes through the pelvic floor muscles.[5]

Unlike other portions of the colon, the rectum does not have distinct taeniae coli.[6] The taeniae blend with one another in the sigmoid colon five centimeters above the rectum, becoming a singular longitudinal muscle that surrounds the rectum on all sides for its entire length.[7][6]

Blood supply and drainage

The blood supply of the rectum changes between the top and bottom portions.[8] The top two thirds is supplied by the superior rectal artery. The lower third is supplied by the middle and inferior rectal arteries.[8]

The superior rectal artery is a single artery that is a continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery, when it crosses the pelvic brim.[8] It enters the mesorectum at the level of S3, and then splits into two branches, which run at the lateral back part of the rectum, and then the sides of the rectum. These then end in branches in the submucosa, which join with (anastamose) with branches of the middle and inferior rectal arteries.[8]

-

Arteries of the pelvis

-

Blood vessels of the rectum and anus

Microanatomy

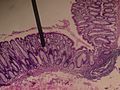

The microanatomy of the wall of the rectum is similar to the rest of the gastrointestinal tract;[9] namely, that it possesses a mucosa with a lining of a single layer of column-shaped cells with mucus-secreting goblet cells interspersed, resting on a lamina propria, with a layer of smooth muscle called muscularis mucosa. This sits on an underlying submucosa of connective tissue, surrounded by a muscularis propria of two bands of muscle, an inner circular band and an outer longitudinal one.[10] There are a higher concentration of goblet cells in the rectal mucosa than other parts of the gastrointestinal tract.[9]

The lining of the rectum changes sharply at the line where the rectum meets the anus. Here, the lining changes from the column-shaped cells of the rectum to multiple layers of flat cells.[9]

-

Cross-section microscopic shot of the rectal wall

-

Dog rectum cross-section (40×)

-

Microscopic cross-section of the rectum of a dog (400×), showing a high concentration of goblet cells in amongst the column-shaped lining. Goblet cells can be seen as the circular cells with a clear inner material (cytoplasm).

Function

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (January 2022) |

The rectum acts as a temporary storage site for feces. The rectum receives fecal material from the descending colon, transmitted through regular muscle contractions called peristalsis.[11] As the rectal walls expand due to the materials filling it from within, stretch receptors from the nervous system located in the rectal walls stimulate the desire to pass feces, a process called defecation.[11]

An internal and external anal sphincter, and resting contraction of the puborectalis, prevent leakage of feces (fecal incontinence). As the rectum becomes more distended, the sphincters relax and a reflex expulsion of the contents of the rectum occurs. Expulsion occurs through contractions of the muscles of the rectum.[11]

The urge to voluntarily defecate occurs after the rectal pressure increases to beyond 18 mmHg; and reflex expulsion at 55 mmHg. In voluntary defecation, in addition to contraction of the rectal muscles and relaxation of the external anal sphincter, abdominal muscle contraction, and relaxation of the puborectalis muscle occurs. This acts to make the angle between the rectum and anus straighter, and facilitate defecation.[11]

Clinical significance

Examination

For the diagnosis of certain ailments, a rectal exam may be done. These include faecal impaction, prostatic cancer and benign prostatic hypertrophy in men, faecal incontinence, and internal haemorrhoids.[12] Forms of medical imaging used to examine the rectum include CT scans and MRI scans. An ultrasound probe may be inserted into the rectum to view nearby structures such as the prostate.

Colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy are forms of endoscopy that use a guided camera to directly view the rectum. The instruments may have the ability to take biopsies if needed, for diagnosis of diseases such as cancer. A proctoscope is another instrument that is used to visualise the rectum.

Body temperature can also be taken in the rectum. Rectal temperature can be taken by inserting a medical thermometer not more than 25 mm (0.98 in) into the rectum via the anus. A mercury thermometer should be inserted for 3 to 5 minutes; a digital thermometer should remain inserted until it beeps. Normal rectal temperature generally ranges from 36 to 38 °C (97 to 100 °F) and is about 0.5 °C (32.9 °F) above oral (mouth) temperature and about 1 °C (34 °F) above axilla (armpit) temperature.[citation needed] Availability of less invasive temperature-taking methods including tympanic (ear) and forehead thermometers has facilitated reduced use of this method.

Route of administration

Some medications are also administered via the rectum (Latin: per rectum).[13] By their definitions, suppositories are inserted, and enemas are injected into the rectum.[14][15] Medications might be given via the rectum to relieve constipation, to treat conditions near the rectum, such as fissures or haemorrhoids, or to give medications that are systemically active when taking them by mouth is not possible.[16] People do not tend to like medications administered by this route because of both cultural issues, discomfort, and issues that may affect the medication working, such as leakage.[16]

Constipation

One cause of constipation is faecal impaction in the rectum, in which a dry, hard stool forms.[citation needed] Constipation is most commonly due to dietary and lifestyle factors such as inadequate hydration, immobility, and lack of dietary fibre, although there are many potential causes.[17] Such causes may include obstruction because of narrowing, local disease (such as Crohn's disease, fissures or haemorrhoids), or diseases affecting the neurological control of the bowel, or slow bowel transit time, including spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis; use of medications such as opioids, and conditions such as diabetes mellitus, as well as severe illness.[17] High calcium levels and low thyroid activity may also cause constipation.[17]

Testing may be carried out to investigate the cause. This may include blood tests such as biochemistry, calcium levels, thyroid function tests.[17] A digital rectal examination may be performed to see if there is stool in the rectum, and whether there is an obstruction.[17] When symptoms such as weight loss, bleeding through the rectum, or pain are present, additional investigations such as a CT scan may be ordered.[17] If constipation persists despite simple treatments, testing may also include anal manometry to measure pressures in the anus and rectum, electrophysiological studies, and magnetic resonance proctography.[17]

In general however, constipation is treated by improving factors such as hydration, exercise, and dietary fibre.[17] Laxatives may be used. Constipation that persists may require enemas or suppositories. Sometimes, use of the fingers or hand (manual evacuation) is required.[citation needed] Although peristalsis in the colon delivers material to the rectum, laxatives such as bisacodyl or senna that induce peristalsis in the large bowel do not appear to initiate peristalsis in the rectum. They induce a sensation of rectal fullness and contraction that frequently leads to defecation, but without the distinct waves of activity characteristic of peristalsis.[18]

Inflammation

- Proctitis is inflammation of the anus and the rectum.

- Ulcerative colitis, one form of inflammatory bowel disease that causes ulcers that affect the rectum. This may be episodic, over a person's lifetime. These may cause blood to be visible in the stool. As of 2014[update], the cause is unknown.

Cancer

- Rectal cancer, a subgroup of colorectal cancer specific to the rectum.

Other diseases

Other diseases of the rectum include:

- Rectal prolapse, referring to the prolapse of the rectum into the anus or external area. This is commonly caused by a weakened pelvic floor after childbirth

- In the context of mesenteric ischemia, the upper rectum is sometimes referred to as Sudeck's point and is of clinical importance as a watershed region between the inferior mesenteric artery circulation and the internal iliac artery circulation via the middle rectal artery and thus prone to ischemia. Sudeck's point is often referred to along with Griffith's point at the splenic flexure as a watershed region.

Society and culture

Sexual stimulation

Due to the proximity of the anterior wall of the rectum to the vagina in females or to the prostate in males, and the shared nerves thereof, the rectum is an erogenous zone and its stimulation or penetration can result in sexual arousal.[19]

History

Etymology

English rectum is derived from the Latin intestinum rectum[20] 'straight gut',[21][22] a calque[23][24] of Ancient Greek ἀπευθυσμένον ἔντερον, derived from ἀπευθύνειν, to make straight,[25] and ἔντερον, gut,[25] attested in the writings of Greek physician Galen.[23][24] During his anatomic investigations on animal corpses, Galen observed the rectum to be straight instead of curved as in humans.[23][24] The expressions ἀπευθυσμένον ἔντερον and intestinum rectum are therefore not appropriate descriptions of the rectum in humans. Apeuthysmenon[26] is the Latinization of ἀπευθυσμένον and euthyenteron[27] has a similar meaning (εὐθύς 'straight[25]). Much of the knowledge of the anatomy of the rectum comes from detailed descriptions provided by Andreas Vesalius in 1543.[28]

See also

References

- ^ Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- ^ "12. Colon and Rectum" (PDF), AJCC Cancer Staging Atlas, American Joint Committee on Cancer, 2006, p. 109, archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-12, retrieved 2017-09-10

- ^ a b Wolff BG, Fleshman JW, Beck DE, Pemberton JH, Wexner SD, Church JM, Garcia-Aguilar J, Roberts PL, Saclarides TJ, eds. (2007). The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-24846-2.

- ^ Wang, Yun Hwa W.; Wiseman, Jeffrey (2023). "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Rectum". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725930. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ a b Gray's Anatomy 2016, pp. 1146–7.

- ^ a b Gray's Anatomy 2016, p. 1137.

- ^ Sneh Agarwal (January–March 2012). "Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor and Anal Sphincters" (PDF). JIMSA. 25 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ^ a b c d Gray's Anatomy 2016, p. 1151.

- ^ a b c Wheater's 2013, p. 273.

- ^ Wheater's 2013, pp. 252–4.

- ^ a b c d Ganong's 2019, p. 492–4.

- ^ O'Connor NJ, Talley S (2009). Clinical examination : a systematic guide to physical diagnosis (6th ed.). Chatswood, N.S.W.: Elsevier Australia. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-7295-3905-0.

- ^ Davidson's 2018, p. 17.

- ^ "Definition of ENEMA". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- ^ "Definition of SUPPOSITORY". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- ^ a b Hua S (2019-10-16). "Physiological and Pharmaceutical Considerations for Rectal Drug Formulations". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 10: 1196. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01196. PMC 6805701. PMID 31680970.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davidson's 2018, pp. 786–7.

- ^ Hardcastle JD, Mann CV (October 1968). "Study of large bowel peristalsis". Gut. 9 (5): 512–20. doi:10.1136/gut.9.5.512. PMC 1552760. PMID 5717099.

- ^ Walton, Alice Bryte; Stelmar, Jenna; Carter, Eric; Duralde, Erin (2021). "Anal Sex Practices and Rectal Erogenous Zones: An Anatomic Questionnaire Based Study".

- ^ Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT) (1998). Terminologia Anatomica. Stuttgart: Thieme.

- ^ Schreger CH (1805). "Synonymia anatomica. Synonymik der anatomischen Nomenclatur". In Fürth (ed.). im Bureau für Literatur.

- ^ Lewis CT, Short C (1879). A Latin dictionary founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b c Hyrtl J (1880). Onomatologia Anatomica. Geschichte und Kritik der anatomischen Sprache der Gegenwart. Wien: Wilhelm Braumüller. K.K. Hof- und Universitätsbuchhändler.

- ^ a b c Triepel H (1910). Die anatomischen Namen. Ihre Ableitung und Aussprache. Mit einem Anhang: Biographische Notizen (Dritte Auflage ed.). Wiesbaden: Verlag J.F. Bergmann.

- ^ a b c Liddell HG, Scott R, Jones HS, McKenzie R (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Kossmann R (1895). "Die gynäcologische Anatomie und ihre zu Basel festgestellte Nomenclatur". Monatsschrift für Geburtshülfe und Gynaekologie. 2 (6): 447–472.

- ^ Gabler E, Winkler TC (1881). Latijnsch-Hollandsch woordenboek over de geneeskunde en natuurkundige wetenschappen (2nd ed.). Leiden: A.W. Sijthoff.

- ^ Beck DE, Roberts PL, Saclarides TJ, Senagore AJ, Stamos MJ, Nasseri Y (2011). The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery: Second Edition. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4419-1581-8.

Sources

- Barrett KE, Barman SM, Yuan JX, Brooks H (2019). Ganong's review of medical physiology (26th ed.). New York. ISBN 9781260122404. OCLC 1076268769.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ralston SH, Penman ID, Strachan MW, Hobson RP (2018). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

- Solomon EP, Schmidt RR, Adragna PJ (1990). Human anatomy & physiology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Sunders College Publishing. ISBN 0-03-011914-6.

- Standring S, ed. (2016). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Young B, O'Dowd G, Woodford P (2013). Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. ISBN 9780702047473.

External links

- Cross section image: pembody/body15a—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Anatomy image:7808 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy photo:43:11-0101 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center