Cryptic crossword

A cryptic crossword is a crossword puzzle in which each clue is a word puzzle. Cryptic crosswords are particularly popular in the United Kingdom, where they originated,[1] as well as Ireland, the Netherlands, and in several Commonwealth nations, including Australia, Canada, India, Kenya, Malta, New Zealand, and South Africa. Compilers of cryptic crosswords are commonly called setters in the UK[2] and constructors in the US. Particularly in the UK, a distinction may be made between cryptics and quick (i.e. standard) crosswords, and sometimes two sets of clues are given for a single puzzle grid.

Cryptic crossword puzzles come in two main types: the basic cryptic in which each clue answer is entered into the diagram normally, and themed or variety cryptics, in which some or all of the answers must be altered before entering, usually in accordance with a hidden pattern or rule which must be discovered by the solver.

History and development

[edit]Cryptic crosswords originated in the UK. The first British crossword puzzles appeared around 1923 and were purely definitional, but from the mid-1920s they began to include cryptic material: not cryptic clues in the modern sense, but anagrams, classical allusions, incomplete quotations, and other references and wordplay. Torquemada (Edward Powys Mathers), who set for The Saturday Westminster from 1925 and for The Observer from 1926 until his death in 1939, was the first setter to use cryptic clues exclusively and is often credited as the inventor of the cryptic crossword.[3]

The first newspaper crosswords appeared in the Sunday and Daily Express from about 1924. Crosswords were gradually taken up by other newspapers, appearing in the Daily Telegraph from 1925, The Manchester Guardian from 1929 and The Times from 1930. These newspaper puzzles were almost entirely non-cryptic at first and gradually used more cryptic clues, until the fully cryptic puzzle as known today became widespread. In some papers this took until about 1960. Puzzles appeared in The Listener from 1930, but this was a weekly magazine rather than a newspaper, and the puzzles were much harder than the newspaper ones, though again they took a while to become entirely cryptic. Composer Stephen Sondheim, a lover of puzzles, is credited with introducing cryptic crosswords to American audiences, through a series of puzzles he created for New York magazine in 1968 and 1969.[4][5][6]

Torquemada's puzzles were extremely obscure and difficult, and later setters reacted against this tendency by developing a standard for fair clues, ones that can be solved, at least in principle, by deduction, without needing leaps of faith or insights into the setter's thought processes.

The basic principle of fairness was set out by Listener setter Afrit (Alistair Ferguson Ritchie) in his book Armchair Crosswords (1946), wherein he credits it to the fictional Book of the Crossword:

We must expect the composer to play tricks, but we shall insist that he play fair. The Book of the Crossword lays this injunction upon him: "You need not mean what you say, but you must say what you mean." This is a superior way of saying that he can't have it both ways. He may attempt to mislead by employing a form of words which can be taken in more than one way, and it is your fault if you take it the wrong way, but it is his fault if you can't logically take it the right way.

An example of a clue which cannot logically be taken the right way:

Here the composer intends the answer to be DERBY, with "hat" the definition, "could be" the anagram indicator, and BE DRY the anagram fodder. I.e., "derby" is an anagram of "be dry". But "be" is doing double duty, and this means that any attempt to read the clue cryptically in the form "[definition] [anagram indicator] [fodder]" fails: if "be" is part of the anagram indicator, then the fodder is too short, but if it is part of the fodder, there is no anagram indicator; to be a correct clue it would have to be "Hat could be be dry (5)", which is ungrammatical. A variation might read Hat turns out to be dry (5), but this also fails because the word "to", which is necessary to make the sentence grammatical, follows the indicator ("turns out") even though it is not part of the anagram indicated.

Torquemada's successor at The Observer was Ximenes (Derrick Somerset Macnutt), and in his influential work, Ximenes on the Art of the Crossword Puzzle (1966), he set out more detailed guidelines for setting fair cryptic clues, now known as "Ximenean principles" and sometimes described by the phrase "square-dealing".[7] The most important of them are tersely summed up by Ximenes' successor Azed (Jonathan Crowther):

- a precise definition

- a fair subsidiary indication

- nothing else

The Ximenean principles are adhered to most strictly in the subgenre of advanced cryptics—difficult puzzles using barred grids and a large vocabulary. Easier puzzles often have more relaxed standards, permitting a wider array of clue types, and allowing a little flexibility. The popular Guardian setter Araucaria (John Galbraith Graham) was a noted non-Ximenean, celebrated for his witty, if occasionally unorthodox, clues.

Popularity

[edit]Most of the major national newspapers in the UK carry both cryptic and concise (quick) crosswords in every issue. The puzzle in The Guardian is well loved for its humour and quirkiness, and quite often includes puzzles with themes, which are extremely rare in The Times.[8]

Many Canadian newspapers, including the Ottawa Citizen, Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail, carry cryptic crosswords.

Cryptic crosswords do not commonly appear in U.S. publications, although they can be found in magazines such as GAMES Magazine, The Nation, The New Yorker, Harper's, and occasionally in the Sunday New York Times. The New York Post reprints cryptic crosswords from The Times. In April 2018, The New Yorker published the first of a new weekly series of cryptic puzzles.[9] Other sources of cryptic crosswords in the U.S. (at various difficulty levels) are puzzle books, as well as UK and Canadian newspapers distributed in the U.S. Other venues include the Enigma, the magazine of the National Puzzlers' League, and formerly, The Atlantic Monthly. The latter puzzle, after a long and distinguished run, appeared solely on The Atlantic's website for several years, and ended with the October 2009 issue. A similar puzzle by the same authors now appears every four weeks in The Wall Street Journal, beginning in January 2010.[10] Cryptic crosswords have become more popular in the United States in the years following the COVID-19 lockdowns with several "indie" outlets and setters.[11]

Cryptic crosswords are very popular in Australia. Most Australian newspapers will have at least one cryptic crossword, if not two. The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age in Melbourne publish daily cryptic crosswords, including Friday's challenging cryptic by 'DA' (David Astle). "Lovatts", an Australian puzzle publisher, regularly issues cryptic crossword puzzle books.

How cryptic clues work

[edit]A cryptic clue leads to its answer only if it is read in the right way. What the clue appears to say when read normally (the surface reading) is usually a distraction with nothing to do with the solution. The challenge is to find the way of reading the clue that leads to the solution. A typical clue consists of two parts:

- The straight or definition. This is in essence the same as any non-cryptic crossword clue: a synonym for the answer. It usually exactly matches the part of speech, tense, and number of the answer, and usually appears at the start or end of a clue.

- The cryptic, subsidiary indication or wordplay. This gives the solver some instructions on how to get to the answer in another (less literal) way. The wordplay parts of clues can be obscure, especially to a newcomer, but they tend to utilise standard rules and conventions which become more familiar with practice.

Sometimes the two parts of the clue are joined with a link word or phrase such as from, gives or could be. One of the tasks of the solver is to find the boundary between the definition and the wordplay, and insert a mental pause there when reading the clue cryptically.

There are many sorts of wordplay, such as anagrams and double definitions, but they all conform to rules. The crossword setters do their best to stick to these rules when writing their clues, and solvers can use these rules and conventions to help them solve the clues. Noted cryptic setter Derrick Somerset Macnutt (who wrote cryptics under the pseudonym of Ximenes) discusses the importance and art of fair cluemanship in his seminal book on cryptic crosswords, Ximenes on the Art of the Crossword (1966, reprinted 2001).[12]

Because a typical cryptic clue describes its answer in detail and often more than once, the solver can usually have a great deal of confidence in the answer once it has been determined. The clues are "self-checking." This is in contrast to non-cryptic crossword clues which often have several possible answers and force the solver to use the crossing letters to distinguish which was intended.

Here is an example (taken from The Guardian crossword of 6 August 2002, set by "Shed").

- 15D Very sad unfinished story about rising smoke (8)

is a clue for TRAGICAL. This breaks down as follows.

- 15D indicates the location and direction (down) of the solution in the grid

- "Very sad" is the definition

- "unfinished story" gives TAL (tale with one letter missing; i.e., unfinished)

- "rising smoke" gives RAGIC (a cigar is a "smoke", and this is a down clue so "rising" indicates that cigar should be written up the page; i.e., backwards)

- "about" means that the letters of TAL should be put either side of RAGIC, giving TRAGICAL

- "(8)" says that the answer is a single word of eight letters.

There are many codewords or indicators that have a special meaning in the cryptic crossword context. (In the example above, "about", "unfinished" and "rising" all fall into this category). Learning these, or being able to spot them, is a useful and necessary part of becoming a skilled cryptic crossword solver.

Compilers or setters often use slang terms and abbreviations, generally without indication, so familiarity with these is important for the solver. Abbreviations may be as simple as west = W, New York = NY, but may also be more difficult.[13] Words that can mean more than one thing are commonly exploited; often the meaning the solver must use is completely different from the one it appears to have in the clue. Some examples are:

- Bloomer – often means flower (a thing that blooms).

- Flower – often means river (a thing that flows).

- Runner – also often river (a thing that runs to the sea)

- Lead – could be the metal, an electric cable, or the verb.

- Nice – if capitalized as the first word, could either be 'amiable' or the French city. Thus Nice friend often clues the letters ami.

- Novel – could be a book, or a word for new, or a codeword indicating an anagram.

- Permit – could be a noun (meaning license) or a verb (meaning allow).

Of these examples, flower is an invented meaning (using the verb flow and the suffix -er), and cannot be confirmed in a standard dictionary. A similar trick is played in the old clue "A wicked thing" for CANDLE, where the -ed suffix must be understood in its 'equipped with' meaning.[a] In the case of the '-er' suffix, this trick could be played with other meanings of the suffix, but except for river → BANKER (a river is not a 'thing that banks' but a 'thing that has banks'), this is rarely done.

Sometimes compiler, or the name or codename of the compiler (if visible by the crossword), codes for some form of the first-person pronoun (I, me, my, mine).

In the Daily Telegraph back page, Monday 15 March 2017, 7 down, is "Banish spirits with zero ice upsetting imbibing times (8)"; the answer is EXORCIZE: it means "banish spirits", and is ZERO ICE rearranged, including X (described as times). The word "upsetting" indicates an anagram and the word "imbibing" indicates an insertion.

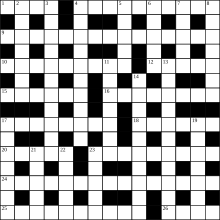

Grids for cryptic crosswords

[edit]A typical cryptic crossword grid is generally 15×15, with half-turn rotational symmetry. Unlike typical American crosswords, in which every square is almost always checked (that is, each square provides a letter for both an across and a down answer), only about half of the squares in a cryptic crossword are checked.

In most daily newspaper cryptic crosswords, grid designs are restricted to a set of stock grids. In the past this was because hot metal typesetting meant that new grids were expensive.[14]

Some papers have additional grid rules. In The Times, for example, all words have at least half the letters checked, and although words can have two unchecked squares in succession, they cannot be the first two or last two letters of a word. The grid shown here breaks one Times grid rule: the 15-letter words at 9 and 24 across each have 8 letters unchecked out of 15. The Independent allows setters to use their own grid designs.

Variety (UK: 'advanced') cryptic crosswords typically use a barred grid with no black squares and a slightly smaller size; 12×12 is typical. Word boundaries are denoted by thick lines called bars. In these variety puzzles, one or more clues may require modification to fit into the grid, such as dropping or adding a letter, or being anagrammed to fit other, unmodified clues; un-clued spaces may spell out a secret message appropriate for the puzzle theme once the puzzle is fully solved. The solver also may need to determine where answers fit into the grid.

A July 2006 "Puzzlecraft" section in Games magazine on cryptic crossword construction noted that for cryptic crosswords to be readily solvable, no fewer than half the letters for every word should be checked by another word for a standard cryptic crossword, while nearly every letter should be checked for a variety cryptic crossword. In most UK advanced ('variety') cryptics, at least three-quarters of the letters in each word are checked.

Regional variation

[edit]British and North American differences

[edit]There are notable differences between British and North American (including Canadian) cryptics. American cryptics are thought of as holding to a more rigid set of construction rules than British ones. American cryptics usually require all words in a clue to be used in service of the wordplay or definition, whereas British ones allow for more extraneous or supporting words. In American cryptics, a clue is only allowed to have one subsidiary indication, but in British cryptics the occasional clue may have more than one; e.g., a triple definition clue would be considered an amusing variation in the UK but unsound in the US.[citation needed][dubious – discuss]

Other languages

[edit]

For the most part, cryptic crosswords are an English-language phenomenon, although similar puzzles are popular in a Hebrew form in Israel (where they are called tashbetsey higayon (תשבצי הגיון) "Logic crosswords")[15] and (as Cryptogram) in Dutch. In Poland similar crosswords are called "Hetman crosswords". 'Hetman', a senior commander, and also the name for a queen in Chess, emphasises their importance over other crosswords. In Finnish, this type of crossword puzzle is known as piilosana (literally "hidden word"), while krypto refers to a crossword puzzle where the letters have been coded as numbers. The German ZEITmagazin has a weekly cryptic crossword called Um die Ecke gedacht and the SZ Magazin features das Kreuz mit den Worten.

In India the Telugu publication Sakshi carries a "Tenglish" (Telugu-English, bilingual) cryptic crossword;[16] the Prajavani and Vijaya Karnataka crossword (Kannada) also employs cryptic wordplay.[17] Enthusiasts have also created cryptic crosswords in Hindi.[18] Since 1994, enigmista Ennio Peres has challenged Italians annually with Il cruciverba più difficile del mondo (The World's Most Difficult Crossword), which has many features in common with English-style cryptics.[19]

In Chinese something similar is the riddle of Chinese characters, where partial characters instead of substrings are clued and combined.

Types of cryptic clues

[edit]Clues given to the solver are based on various forms of wordplay. Nearly every clue has two non-overlapping parts to it: one part that provides an unmodified but often indirect definition for the word or phrase, and a second part that includes the wordplay involved. In a few cases, the two definitions are one and the same, as often in the case of "&lit." clues. Most cryptic crosswords provide the number of letters in the answer, or in the case of phrases, a series of numbers to denote the letters in each word: "cryptic crossword" would be clued with "(7,9)" following the clue. More advanced puzzles may drop this portion of the clue.

Anagrams

[edit]

An anagram is a rearrangement of a certain section of the clue to form the answer.[20] This is usually indicated by a codeword which indicates change, movement, breakage or something otherwise amiss.[b] One example:

- Chaperone shredded corset (6)

gives ESCORT, which means "chaperone" and is an anagram, indicated by the word "shredded", of CORSET.

Anagram clues are characterized by the codeword (the anagram indicator or – among enthusiasts – anagrind) placed adjacent to a word or phrase made up of the letters to be rearranged (the anagram fodder). The indicator tells the solver an anagram exists, and the fodder provides the anagram to be solved. Indicators can come either directly before or directly after the fodder.

In an American cryptic, only the words given in the clue may be anagrammed; in some older puzzles, the words to be anagrammed may be clued and then anagrammed. This kind of clue is called an indirect anagram. For example, in:

- Chew honeydew fruit (5)

"chew" is the indicator, but "honeydew" does not directly provide the letters to be anagrammed. Instead, "honeydew" clues MELON, which can be rearranged to form the solution LEMON – another "fruit". Indirect anagrams are not used in the vast majority of cryptic crosswords, ever since they were criticised by Ximenes in On the Art of the Crossword.[c]

It is common for the setter to use a juxtaposition of indicator and fodder that together form a common phrase, to make the clue appear as normal as possible. For example:

- Lap dancing friend (3)

uses "dancing" as the indicator because it combines naturally with the fodder LAP, disguising the anagram. The solution is PAL ("friend").

Charade

[edit]In a charade or Ikea clue, the answer is formed by joining individually clued words to make a larger word (namely, the answer).[21]

For example:

- Outlaw leader managing money (7)

The answer is BANKING, formed by BAN for "outlaw" and KING for "leader". The definition is "managing money". With this example, the words appear in the same order in the clue as they do in the answer, and no special words are needed to indicate this. However, the order of the parts is sometimes indicated with words such as against, after, on, with or above (in a down clue).

Containers

[edit]A container or insertion clue puts one set of letters inside another.[22] So:

- Apostle's friend outside of university (4)

gives PAUL ("apostle"), by placing PAL ("friend") outside of U ("university").[d]

A similar example:

- Utter nothing when there's wickedness about (5)

The answer is VOICE ("utter"), formed by placing O ("nothing") inside the word VICE ("wickedness").

Other container or insertion indicators are inside, over, around, about, clutching, enters, and the like.

Deletions

[edit]Deletion is a wordplay mechanism which removes some letters of a word to create a shorter word.[23] Deletions consist of beheadments, curtailments, and internal deletions. In beheadments, a word loses its first letter. In curtailments, it loses its last letter, and internal deletions remove an inner letter, such as the middle one.

An example of a beheadment:

- Beheaded celebrity is sailor (3)

The answer would be TAR, another word for "sailor", which is star ("celebrity") without the first letter ("beheaded").

A similar example, but with a specification as to the letter being removed:

- Bird is cowardly, about to fly away (5)

The answer is RAVEN, which means "bird" and is craven, or "cowardly", without the first letter (in this case C, the abbreviation for circa or "about").

Other indicators of beheadment include don't start, topless, and after the first.

An example of curtailment:

- Shout, "Read!" endlessly (3)

The answer is BOO (a "shout"). If you ignore the punctuation, a "read" is a book, and book without its final letter ("endlessly") is the solution.

Other indicators of curtailment include nearly and unfinished.

An example of internal deletion:

- Challenging sweetheart heartlessly (6)

The answer is DARING, which means "challenging", and is darling without its middle letter, or "heartlessly".[e]

Double definition

[edit]A clue may, rather than having a definition part and a wordplay part, have two definition parts.[24] Thus:

- Not seeing window covering (5)

would have the answer BLIND, because blind can mean both "not seeing" and "window covering". Note that since these definitions come from the same root word, an American magazine might not allow this clue. American double definitions tend to require both parts to come from different roots, as in this clue:

- Eastern European buff (6)

This takes advantage of the two very different meanings (and pronunciations) of POLISH, the one with the long o sound meaning 'someone from Poland', and the one with the short o sound meaning 'make shiny'.

These clues tend to be short; in particular, two-word clues are almost always double-definition clues.

In the UK, multiple definitions are occasionally used; e.g.:

- Blue swallow feathers fell from above (4)

is a quintuple definition of DOWN ("blue" (sad), "swallow" (drink), "feathers" (plumage), "fell" (cut down) and "from above"),[25] but in the US this would be considered unsound.

Some British newspapers have an affection for quirky clues of this kind where the two definitions are similar:

- Let in or let on (5) – ADMIT

Note that these clues do not have clear indicator words.

Hidden words

[edit]In hidden words, embedded words or telescopic clues, the solution itself is written within the clue – either as part of a longer word or across more than one word.[26] For example:

- Found ermine, deer hides damaged (10)

gives UNDERMINED, which means (cryptically at least) "damaged" and appears across "Found ermine deer" (as indicated by "hides").[f]

Possible indicators of a hidden clue include in part, partially, in, within, hides, conceals, some, and held by.

Another example:

- Introduction to do-gooder canine (3)

gives DOG, which is the first part of, or "introduction to", the word "do-gooder", and means "canine".

The opposite of a hidden word clue, where letters missing from a sentence have to be found, is known as a Printer's Devilry, and appears in some advanced cryptics.

There are several common variations on hidden word clues:

Initial or final letters

[edit]The first or last letters of part of the clue are put together to give the answer.

An example of an initialism:

- Initially amiable person eats primate (3)

The answer would be APE, which is a type of "primate". "Initially" signals that you must take the first letters of "amiable person eats".

Another example would be:

- At first, actor needing new identity emulates orphan in musical theatre (5)

The answer would be ANNIE, the name of a famous "orphan in musical theatre". This is obtained from the first letters of "actor needing new identity emulates".

Words that indicate initialisms also include firstly, primarily and to start.

It is possible to have initialisms just for certain parts of the clue. It is also possible to employ the same technique to the end of words. For example:

- Old country lady went round Head Office initially before end of day (7)

The answer would be DAHOMEY, which used to be a kingdom in Africa (an "old country"). Here, we take the first letters of only the words "Head Office" (HO) and we take the "end of" the word "day" (Y). The letters of the word DAME, meaning "lady", are then made to go around the letters HO to form DAHOMEY.

That the solver should use the last letters may also be indicated by such words as ends, tails, last etc. For instance:

- Bird with tips of rich aqua, yellow, black (4)

Would be HAWK (a "bird") based on the letters at the ends of ("tips of") "rich aqua, yellow, black".

Odd or even letters

[edit]Either the odd or even letters of words in the clue give the answer. An example is:

- Odd stuff of Mr. Waugh is set for someone wanting women to vote (10)

The answer would be SUFFRAGIST, which is "someone wanting women to vote". The word "odd" indicates that we must take only the odd-indexed letters of the rest of the clue ("stuff of Mr. Waugh is set"), i.e. every other letter beginning with the first.

Homophones

[edit]Homophones are words that sound the same but have different meanings, such as night and knight. Homophone clues always have an indicator word or phrase that has to do with being spoken or heard.[27] Examples of homophone indicators include reportedly, they say, utterly (here treated as utter(ing)-ly and not with its usual meaning), vocal, to the audience, auditioned, by the sound of it, is heard, in conversation and on the radio. Broadcast is a particularly devious indicator as it could indicate either a homophone or an anagram.

An example of a homophone clue is

- We hear twins shave (4)

which is a clue for PARE, which means "shave" and is a homophone of pair, or "twins". The homophone is indicated by "we hear".

If the two homophones are the same length, the clue should be phrased in such a way that only one of them can be the answer. This is usually done by having the indicator adjacent to the word that is not the definition; therefore, in the previous example, "we hear" was adjacent to "twins" and the answer must therefore be PARE rather than PAIR. The indicator could come between the homophones if they were of different lengths and the enumeration was given, such as in the case of right and rite.[28]

Letter banks

[edit]The letter bank form of cluing consists of a shorter word (or words) containing no repeated letters (an "isogram"), and a longer word or phrase built by using each of these letters (but no others) at least once but repeating them as often as necessary. This type of clue has been described by American constructors Joshua Kosman and Henri Picciotto, who write the weekly puzzle for The Nation. The shorter word is typically at least three or four letters in length, while the target word or phrase is at least three letters longer than the bank word. For example, the four letters in the word TENS can be used as a bank to form the word TENNESSEE. Typically, the clue contains indicator words such as "use," "take," or "implement" to signal that a letter bank is being employed.

A more complicated example of a letter bank is:

- Composer taking and retaking ingredients of Advil? Not! (7,7)[29]

In this case, "taking and retaking ingredients" signals that the letters of both ADVIL and NOT form a letter bank. Those letters yield a "composer", and the solution, ANTONIO VIVALDI.

Kosman and Picciotto consider this to be a newer and more complicated form of cluing that offers another way, besides the anagram, of mixing and recombining letters.[30]

Reversals

[edit]A word that gets turned around to make another is a reversal.[23] For example:

- Returned beer fit for a king (5)

The answer is REGAL. LAGER ("beer") is reversed ("returned") to yield the solution ("fit for a king").

Other indicator words include receding, in the mirror, going the wrong way, returns, reverses to the left or left (for across clues), and rising, overturned or mounted or comes up (for down clues).

Cryptic definition

[edit]Here the clue appears to say one thing, but with a slight shift of viewpoint it says another. For example:

- Flower of London? (6)

gives THAMES, a flow-er of London. Here, the surface reading suggests a blossom, which disguises the fact that the name of a river is required. Notice the question mark: this is often (though by no means always) used by compilers to indicate this sort of clue is one where you need to interpret the words in a different fashion. The way that a clue reads as an ordinary sentence is called its surface reading and is often used to disguise the need for a different interpretation of the clue's component words.

This type of clue is common in British and Canadian cryptics but is generally unused in American cryptics;[31] in American-style crosswords, a clue like this is generally called a punny clue[citation needed]. It's almost certainly the oldest kind of cryptic clue:[citation needed] cryptic definitions appeared in the UK newspaper puzzles in the late 1920s and early 1930s that mixed cryptic and plain definition clues and evolved into fully cryptic crosswords.

Spoonerism

[edit]A relatively uncommon clue type,[32] a Spoonerism is a play on words where corresponding consonant clusters are switched between two words in a phrase (or syllables in a word) and the switch forms another pair of proper sounding words. For example: "butterfly" = "flutter by".

Both the solution word or phrase and its corresponding Spoonerism are clued for, and the clue type is almost always indicated by reference to William Archibald Spooner himself – with some regions/publications insisting his religious title "Rev." or "Reverend" be included. In contrast to all other clue types, this makes them almost impossible to disguise. But that does not necessarily make them easy.

An example of a Spoonerism clue is:

- He will casually put down Spooner's angry bear (9)

The answer is LITTERBUG ("he will casually put down"). The Spoonerism is bitter lug, i.e. "angry" and "bear" (as in carry).

The vast majority of Spoonerism clues swap the first consonants of words or syllables, but Spoonerisms are not strictly restricted to that form and some setters will take advantage of this. John Henderson (Enigmatist in the Guardian) once clued for RIGHT CLICK using the Spoonerism LIGHT CRICK,[33] which did not sit well with many solvers.

Palindrome

[edit]A clue in which the only hint to the letters in the solution is that it is a Palindrome,[34] for example:

- To and fro action (4)

where the answer is DEED or:

- She's a lady, whichever way you look at it! (5)

where the answer is MADAM.

Reverse anagrams

[edit]A reverse anagram or revenge clue (short for "reverse engineer")[35] is one which gives an anagrammed word in its text, and the solver has to determine the anagrammed word(s) and indicator that make the solution matching the definition. Such clues may or may not use an indicator.[36]

An example from The Guardian:

- Innovative way to make dog run? (6-8)[37]

The phrase "way to make" indicates that the solver should look for a word and anagram indicator that could rearrange to the words DOG RUN; the solution, meaning "innovative," is GROUND-BREAKING.

Revenge clues are not limited to anagrams; for instance, "Quickly grab containers for the setter? (4,2)" indicates a revenge reversal of PANS, or SNAP UP ("quickly grab").

&lit.

[edit]An &lit., literal or all-in-one clue is one where the entire clue simultaneously provides both the definition and the wordplay. &lit. stands for "and literally so", and originates from Derrick Somerset Macnutt (known by his pen name Ximenes),[38] who defined it as meaning: "This clue both indicates the letters or parts of the required word, in one of the ways already explained in this book, and can also be read, in toto, literally, as an indication of the meaning of the whole word, whether as a straight or as a veiled definition."[39] In some publications, particularly in the United States, &lit clues are indicated by an exclamation mark at the end of the clue.[23][38]

For example:

- God incarnate, essentially! (4)

The answer is ODIN. The Norse god Odin is hidden in "God incarnate", as clued by "essentially", but the definition of Odin is also the whole clue, as Odin is essentially a God incarnate.

Another example:

- Spoil vote! (4)

would give the answer VETO. In the cryptic sense, "spoil" indicates an anagram of VOTE. Simultaneously, the whole clue is – with a certain amount of licence allowed to crossword setters – a definition.

Another example:

- E.g., origin of goose (3)

gives the answer EGG. A goose is an example of something that finds its origin in an egg, so the whole clue gives a definition. The clue can also be broken down cryptically: "E.g." loses its full stops to give EG, followed by the first letter of (i.e. the "origin of") the word "goose", G.

Semi-&lit.

[edit]A semi-&lit. clue is a variant of the &lit. where the entire clue still provides the definition, but the wordplay is only given by part of the clue.

For example:

- Dressed up to hear a bit of Puccini? This may be part of it (5,3)[40]

gives OPERA HAT. The whole clue provides a definition of the answer (i.e. something that might be worn while listening to Puccini), but only the first part of the clue is wordplay ("bit of Puccini" cluing P, and "dressed up" clueing an anagram; overall an anagram of TO HEAR A P).[41]

Another example:

- Dog in wild? Yes! (5)[42]

gives DINGO. Only the first part of the clue provides wordplay ("wild" indicating an anagram of DOG IN), but the whole clue can be interpreted as a definition of the answer.[43]

The term clue-as-definition (CAD) can be used as an inclusive descriptor covering both &lit. and semi-&lit. clues.

Other miscellaneous types

[edit]Ximenes identifies various other types of clue in On The Art Of The Crossword (1966) in chapter VII, 'Improvised Clues', including:

- Heads and tails, involving words which have lost their first or last letter, similar to deletions; e.g. "Hard workers have a limit: one exam unfinished (8)", solution: TERMITES (TERM-I-TES, where TES is test missing its last letter).

- Peculiarities of speech, involving words as pronounced by someone with a distinct accent (e.g. Cockney speakers dropping an initial H) or even illness/speech pathology (e.g. words pronounced as if by someone with a blocked nose, lisp or stutter); e.g. "Arry's pronunciation of dame?", solution: DIME.

- Words treated as parts of other words; e.g. "A lifter causes swearing (four letters first) (5)", solution: DAVIT, which would become affidavit if four letters were added to the start.

- Foreign languages, involving non-English words as solutions; e.g. "English writer, but understood by all Frenchmen (4)", solution: MAIS.

- Literary references, involving references to books; e.g. "Procedures followed by Romans (4)", solution: ACTS.

- Outsides, the converse of a hidden word clue; e.g. "Cavalrymen disheartened in Normandy (4)", solution: CAEN.

Initial or final letter clues are also mentioned in this chapter, to be used "When the setter is in real desperation".

Clueing techniques

[edit]Combination clues

[edit]"Combination clues" employ more than one method of wordplay; this is particularly common for longer grid entries.[44] For example:

- Illustrious baron returns in pit (9)

The answer is HONORABLE. "Baron" is reversed (or "returns") to yield NORAB, and put inside HOLE (or "pit") to give the solution (clued by "illustrious").

In this example, the clue uses a combination of Reversal and Hidden clue types:

- Cruel to turn part of Internet torrid (6)

The answer to this clue is ROTTEN. "To turn" indicates a reversal, and "part of" suggests a piece of "Internet torrid"; the solution means "cruel".

Misleading clues

[edit]To make clues more difficult, cryptic constructors will frequently use traditional indicator words in a misleading manner.

- A cryptic crossword on the back page of the Daily Telegraph on 14 March 2012 included the answer ANALYSIS, whose clue was "Close study of broken nails, say (8)" (Say often indicates a homophone, or means 'for example', but here it is part of an anagram.)

- Daily Telegraph back page, 8 November 2012: "Drunk compiler's admitted boob (5)" is parsed as "means 'drunk', MY contains ERR, has 5 letters", which yields MERRY. (Drunk often indicates an anagram, but here serves as the definition.)

- In a crossword by Araucaria, "Araucaria is" coded for IAM (I am) as part of an answer.

Clues valid only on particular days or in particular areas

[edit]- A cryptic crossword in the Sunday Telegraph on Easter Sunday 2014 had an anagram clue whose answer was EASTER SUNDAY, and its definition part was "today".

- Daily Telegraph on 8 April 2019, page 30: 5 down: "Parade one month ago (5,4)": its answer was MARCH PAST; that clue would be valid only in April each year.

- In a cryptic crossword in the British newspaper Daily Telegraph (20 April 2017), the clue "Irritating proverb we're told (4) (SORE = "saw") depends on a homophony which only happens in non-rhotic pronunciation such as in British English.

Bits and pieces

[edit]Abbreviations are popular with crossword compilers for cluing individual letters or short sections of the answer. Consider this clue:

- About to come between little Desmond and worker for discourse (7)

There are two abbreviations used here. "About" is abbreviated C (for "circa"), and "little Desmond" indicates that the diminutive of Desmond (namely, DES) is required. The C is "to come between" DES and ANT (a worker; note that compilers also use "worker" to stand for 'bee' or 'hand'), giving DESCANT, which means "discourse".

Compilers use many of these crossword abbreviations.

Another type of abbreviation in clues might be words that refer to letters. For example, 'you' refers to the letter U, 'why' refers to the letter Y, etc. A clue for instance:

- For example, why didn't you put the country? (5)

The answer is EGYPT. Three abbreviations are used here. "For example" clues the common abbreviation EG (for exempli gratia). "Why" clues the letter Y. The phrase "didn't you put" clues the letters PT (the word "you" refers to the letter U, and word "didn't" indicates that this should be left out of the word "put"). Adding these together gets "the country".

There are many ways in which constructors can clue a part of a clue. In this clue:

- Exclamation of surprise about spectacles, from the top (3)

The word "spectacles" clues OO because these letters look like a pair of spectacles "from the top". The answer is thus COO, which is an "exclamation of surprise" with C coming from circa, clued by "about".

Often, Roman numerals are used to break down words into their component letter groups. E.g. In this clue:

- A team's first supporter is pivotal (4)

The answer is AXIS, and the direct meaning is conveyed by the words "is pivotal". The first A is followed by XI, which is 11 in Roman numerals (referring to the number of players on the field in a cricket or soccer "team"). "First supporter" refers to the letter S, which is the first letter of the word "supporter".

Clueing technique and difficulty

[edit]Cryptic clue styles across newspapers are ostensibly similar, but there are technical differences which result in the work of setters being regarded as either Ximenean or Libertarian (and often a combination of both).

Ximenean rules are very precise in terms of grammar and syntax, especially as regards the indicators used for various methods of wordplay. Libertarian setters may use devices which "more or less" get the message across. For example, when treating the answer BEER the setter may decide to split the word into BEE and R and, after finding suitable ways to define the answer and BEE, now looks to give the solver a clue to the letter R. Ximenean rules would not allow something like "reach first" to indicate that R is the first letter of "reach" because, grammatically, that is not what "reach first" implies. Instead, a phrase along the lines of "first to reach" would be needed as this conforms to rules of grammar. Many Libertarian crossword editors would, however, accept "reach first" as it would be considered to reasonably get the idea across. For instance, a clue following Ximenean rules for BEER (BEE + R) may look as such:

- Stinger first to reach drink (4)

While a clue following Libertarian rules may look as follows:

- Stinger reaches first drink (4)

The Guardian is perhaps the most Libertarian of cryptic crosswords, while The Times is mostly Ximenean. The others tend to be somewhere in between; the Financial Times and Independent tend towards Ximenean, the Daily Telegraph also – although its Toughie crossword can take a very Libertarian approach depending on the setter. None of the major daily cryptics in the UK is "strictly Ximenean"; all allow clues which are just cryptic definitions, and strict Ximenean rules exclude such clues. There are other differences like nounal anagram indicators and in current Times crosswords, unindicated definition by example: "bay" in the clue indicating HORSE in the answer, without a qualification like "bay, perhaps".

In terms of difficulty, Libertarian clues can seem impenetrable to inexperienced solvers. However, more significant is the setter him/herself. Crosswords in the Times and Daily Telegraph are published anonymously, so the crossword editor ensures that clues adhere to a consistent house style. Inevitably each setter has an individual (and often very recognisable) approach to clue-writing, but the way in which wordplay devices are used and indicated is kept within a defined set of rules.

In the Guardian, Independent, Financial Times and Telegraph Toughie series the setters' pseudonyms are published, so solvers become familiar with the styles of individual setters rather than house rules. Thus the level of difficulty is associated with the setter rather than the newspaper, though puzzles by individual setters can actually vary in difficulty considerably.

It is effectively impossible, then, to describe one newspaper's crosswords as the toughest or easiest. For newcomers to cryptic puzzles the Daily Telegraph is often regarded as an ideal starting point, but this is contentious. Since all of the newspapers have different styles, concentrating on one of them is likely to lead to proficiency in only one style of clue-writing; moving to a different series, after perhaps years spent with just one, can leave the solver feeling as if they have gone back to square one. The better technique is to simply attempt as many different crosswords as possible, perhaps to find a "comfort zone" but, more importantly, to experience the widest possible range of Ximenean/Libertarian styles.

Variety Cryptics

[edit]"Themed" or "variety" cryptics have developed a small but enthusiastic following in Britain, the United States, and elsewhere. Variety cryptics are arguably among the most difficult of all crossword puzzles, both to compile and to solve, since they often involve alterations to the answers before entry into the grid, meaning that there is no assurance that the cross clues will match up unless properly altered.

As an example, a puzzle entitled "Trash Talk" by Bob Stigger in the June 2019 issue of the U.S. publication Games World of Puzzles included the following instruction:[45]

In this variety cryptic crossword, 18 clue answers are garbage, to be treated according to the mantra "13-Across 6-Across and 40-across." Specifically, six answers are too long for the grid; delete one letter. Six others are too short, double one letter. And six more don't match the crossing letters; anagram them.

Pangrams

[edit]A crossword that includes all the letters of the alphabet within the clue answers is known as a pangram. Crosswords have been set with clue answers that contain all the letters of the alphabet twice, thrice, four times over, and even five times. This last, a pentapangram, was compiled by Maize and published in the i on January 1, 2018.

Cryptic crosswords in specific publications

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]In Britain it is traditional—dating from the cryptic crossword pioneer Edward (Bill) Powys Mathers (1892–1939), who called himself "Torquemada" after the Spanish Inquisitor—for compilers to use evocative pseudonyms. "Crispa", named from the Latin for "curly-headed", who set crosswords for the Guardian from 1954[46] until her retirement in 2004, legally changed her surname to "Crisp" after divorcing in the 1970s. Some pseudonyms have obvious connotations: for example, Torquemada as already described, or "Mephisto" with fairly obvious devilish overtones. Others are chosen for logical but less obvious reasons, though "Dinmutz" (the late Bert Danher in the Financial Times) was produced by random selection of Scrabble tiles.

- The Daily Telegraph/Sunday Telegraph

- The Telegraph, like the Times, does not identify the setter of each puzzle but, unlike the Times, has a regular setter for each day of the week, plus a few occasional setters to cover holidays or sickness. Regular setters include John Halpern, Ray Terrell, Jeremy Mutch, Don Manley, Allan Smith, Steve Bartlett and Richard Palmer. The regular setters as of 1 November 2006 are shown in a photograph here. The crossword editor is Chris Lancaster, who took over from Phil McNeill in early 2018. There is an advanced cryptic called Enigmatic Variations in the Sunday Telegraph, and also a 15×15 blocked-grid puzzle.

- In September 2008 the Telegraph started printing a 'Toughie' crossword as well as the daily puzzle, from Tuesday to Friday. This is described by the paper as "the toughest crossword in Fleet Street" or similar and does include the setter's pseudonym. Comments from some solvers on these puzzles don't always agree with this assessment, rating maybe half of them as close to average broadsheet cryptic difficulty.

- The Guardian

- Notable compilers of The Guardian's cryptic crosswords include Enigmatist, Pasquale, Paul (John Halpern), Rufus (now retired), and the late Bob Smithies (Bunthorne) and Araucaria. The puzzle is edited by Alan Connor.[47]

- The Independent

- The Independent went online only in 2016, but still has a cryptic crossword. Setters include Virgilius, Dac, Phi, Quixote, Nimrod, Monk, Nestor, Bannsider, Anax, Merlin, Mass, Math, Morph, Scorpion, Tees and Punk (John Halpern). The daily puzzle is edited by Eimi (Mike Hutchinson).

- i

- The i newspaper was launched in 2010 as a sister paper to The Independent, but was bought by Johnston Press in February 2016 when The Independent moved to digital-only publication. The fiendish Inquisitor puzzle is edited by John Henderson whose predecessor was the late former Times crossword editor Mike Laws. The crosswords are often themed and may contain a Nina: a hidden feature.

- The National

- Launched in Scotland as "The Newspaper that supports an independent Scotland" on 24 November 2014 after the independence referendum on 18 September. The National has a daily cryptic crossword after a request from readers to include one. The National is the only daily pro-independence newspaper in Scotland and is edited by Sunday Herald editor Richard Walker.

- The Observer

- Home of the famous Azed crossword, which employs a barred grid and a wider vocabulary than standard cryptics, and in conjunction with its predecessors 'Torquemada' and 'Ximenes' is the longest-running series of barred-grid puzzles. On the first Sunday of every month and at Christmas, Azed runs a clue-writing competition, via which many of today's top compilers have learnt their trade. The Observer also features a standard cryptic crossword, the Everyman, compiled by Allan Scott.

- Private Eye

- In the early 1970s the satirical magazine Private Eye had a crossword set by the Labour MP Tom Driberg, under the pseudonym of "Tiresias" (supposedly "a distinguished academic churchman"). It is currently set by Eddie James under the name "Cyclops". This crossword is usually topical, and contains material varying from risqué to rude, in clues, answers and the solver's head; much of the rudeness is by innuendo.[citation needed] It also often includes references to the content of the rest of the magazine, or its jargon in which, for example, the current monarch of the UK is "Brian" and the last one "Brenda". The £100 prize for the first correct solution opened is unusually high for a crossword and attracts many entrants.[citation needed]

- The Radio Times

- Roger Prebble has compiled the cryptic crossword since 1999.

- Significance

- Significance is a joint publication between the American Statistical Association and the Royal Statistical Society; it contains a cryptic crossword in its puzzle section. The magazine offers a randomly awarded $150 or £100 to spend on Wiley books for those that submit a correct entry.

- The Spectator

- Cryptics in the weekly Spectator often have a specific theme, such as a tribute to a public figure who has died recently or a historic event that has its anniversary this week. As in most British periodicals, the cryptic in the Spectator is numbered: in the Spectator's case, a puzzle's theme may be related to its specific number (such as a historic event that occurred in the year corresponding to the four-digit number of the puzzle for that week). Compilers include Doc (the puzzle editor as well as chief setter), Dumpynose (an anagram for 'Pseudonym') and Columba.

- The Sunday Times

- The Sunday Times cryptic crossword is compiled in rotation by three setters: Jeff Pearce, Dean Mayer and David McLean, the latter taking over from Tim Moorey in January 2016. (Mr Moorey's final puzzle included the hidden message 'Farewell from Tim'; he continues to set Mephisto puzzles.) The position of puzzles editor is now held by Peter Biddlecombe. Until her retirement in December 2010, Barbara Hall was puzzles editor for 32 years, and wrote about half the paper's cryptic crosswords. The Sunday Times is also home to the difficult barred-grid Mephisto puzzle, currently set in rotation by Don Manley, Paul McKenna and Tim Moorey. Previous Mephisto setters were Richard Kilner (only setter, 1959 to 1973), Richard Whitelegg (only setter, 1973 to 1995), Chris Feetenby (1995-2008) and Mike Laws (1995-2011).[48]

- The Times

- Adrian Bell was the first to set The Times crossword from 1930[49] and was one of those responsible for establishing its distinctive cryptic style. (The Times was a relatively late adopter: the Telegraph crossword started in 1925, and the Guardian in 1929.) The Times has a team of about 15 setters, many of whom set puzzles for other papers. The setter of each puzzle is not identified. The Times also has "jumbo" (23×23) puzzles in the Saturday edition and since 1991 has provided a home for the famously difficult advanced cryptic puzzle which used to appear in the BBC's The Listener.

- The daily Times puzzle is syndicated in the New York Post (US) and The Australian (Aus) papers. In both cases, the puzzle appears some weeks after it appeared in The Times.

- The Times introduced the Quick Cryptic crossword on March 24, 2014.[50] It is a smaller and easier version of the paper's main daily cryptic crossword, and is designed to be more accessible to beginners and those who want a quicker challenge. The Quick Cryptic is 13x13 squares in size, compared to the main cryptic's 15x15, and uses simpler wordplay. It also features semi-anonymous setters, so you can see who created the puzzle but not their real name.[51]

- In October 2007, The Bugle—a TimesOnline podcast by John Oliver and Andy Zaltzman—introduced the first, revolutionary "Audio Cryptic Crossword."[52]

- Viz magazine

- Since 2009 the adult comic magazine Viz has incorporated a cryptic crossword credited to Anus. This is a collaboration of two setters, one of whom has a minor role in supplying some pre-written clues. In keeping with the comic's "top shelf" status the puzzle content is an amalgam of humour and obscenity, although the clueing style retains both Libertarian and Ximenean disciplines.

Elsewhere

[edit]- The Age (Australia)

- (see Sydney Morning Herald)

- The Atlantic (US)

- The Atlantic magazine had a long-running variety cryptic crossword, known as the Puzzler, created by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon beginning in 1977,[53] available only online since March 2006. The final original Puzzler was published in August 2009 for the September issue. An online archive of Puzzlers going back to 1997 is still available.[54]

- The Browser (US)

- This online news-aggregator offers a weekly American cryptic to its subscribers.

- Games World of Puzzles (US)

- Originally two separate publications, "GAMES" and "World of Puzzles", the two were merged in 2014 to become "GAMES WORLD OF PUZZLES," published nine times a year. The publication currently features two basic cryptics and two variety cryptics in each issue. Some other puzzles in the publication include cryptic elements, such as double definition puzzles or hidden word puzzles.

- The Globe and Mail (Canada)

- "Canada's national newspaper" includes a daily cryptic somewhat less difficult than its British cousins. The crossword also comes with another set of "Quick Clues" (American-style) which provide a completely different set of answers. Fraser Simpson compiles the Saturday cryptic;[55] he also used to compile an advanced cryptic in The Walrus. Until 2015, once a year on Canada Day, The Globe published a large 24×24 bar-diagram cryptic.

The Geraldine News (New Zealand)

- This weekly local paper carries a cryptic once a month. It is compiled by Geraldine resident Jim Walton and titled JW Cryptic Crossword. As at April 2019, Jim had provided 244 cryptic crosswords for the paper.

- Harper's (US)

- This magazine features a monthly variety cryptic by Richard Maltby, Jr., and previously also by E. R. Galli, aimed at advanced solvers.[56]

- The Hindu (India)

- The Hindu newspaper carries cryptic crosswords in the main paper from Monday to Saturday, and a much tougher Sunday Crossword in the Sunday Magazine supplement. The weekday crosswords are set by setters with the pseudonyms Gridman, Arden, Incognito, Afterdark, Buzzer, Neyartha, Scintillator, xChequer, Lightning, Sunnet, Spinner, Aspartame, Mac, Dr. X, KrisKross, Hypatia among others.[57] In every cycle, a setter publishes a certain number of crosswords allotted to him or her, unlike British papers where things are mostly random. The Sunday Crossword is a syndicated crossword from the UK newspaper The Observer.

- The first setter of the Monday-Saturday cryptic crosswords was Retired Admiral Ram Dass Katari of the Indian Navy,[58] who took up the task in 1971 at the request of Gopalan Kasturi, then editor of The Hindu. The crossword has a regular following, and while The Hindu publishes the solutions on the following day, the annotated solution is put up at the website 'The Hindu Crossword Corner' by a group of solvers on the same day.

- Irish Times

- The Irish Times originally provided a daily puzzle by "Crosaire" (Derek Crozier), which featured a fairly unorthodox style of clue-writing. The paper continued to run his puzzles after his death in April 2010. The last of Crozier's crosswords was published in the Irish Times on 22 October 2011. The Irish Times' cryptic crossword is currently set by Crosaire's successor Crosheir.[59]

- The Listener (New Zealand)

- This weekly magazine includes a cryptic by David Tossman, who took over from RWH (Ruth Hendry) in 1997. RWH had been providing a mixed (some cryptic clues) puzzle since 1940.

- Lovatts Crosswords

- Lovatts Crosswords are a range of magazines sold throughout the UK, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. Christine Lovatt is the main cryptic compiler, and she has been so for 30 years.

- The Nation (US)

- This liberal American political weekly featured a weekly cryptic puzzle from 1947 to 2020. Frank W. Lewis wrote the puzzle from late 1947 until his retirement in late 2009. Lewis developed one of the most recognizably personal styles of cryptic setting, and The Nation published book collections of his puzzles. From December 2011, the weekly puzzle was written by Joshua Kosman and Henri Picciotto. Their last cryptic for the magazine was published in March 2020.[60] Kosman and Picciotto continue to offer a weekly cryptic at their website leftfieldcryptics.com.[61][11]: 35

- The National Post (Canada)

- Carries a weekly puzzle by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon.

- New York Magazine

- Stephen Sondheim's puzzles for New York Magazine have been collected in book form. Sondheim is himself a collector of old-time puzzles and board games.

- New Yorker

- For some of the time that this magazine was edited by Tina Brown (1997–1999), it included a small (8×10) barred-grid cryptic crossword, set by a range of American and Canadian setters. These puzzles are also available in a book collection,[62] and were republished online.[63]

- Starting in June of 2021, a new cryptic is published each week on Sunday. It uses the same 8x10 barred-grid.[64] The New Yorker stopped publishing cryptic crosswords in March 2024.[65]

- New York Times

- Two weeks in every 18, the "variety puzzle" in the Sunday edition is a cryptic crossword, usually by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon, Richard Silvestri, or Fraser Simpson. One week in 18, it is a "Puns and Anagrams" puzzle, a relic of a 1940s attempt to introduce cryptic puzzles to the US.

- The New Zealand Herald (Auckland, New Zealand)

- The weekend edition features a cryptic crossword by "Kropotkin" (Rex Benson) in addition to The Observer's 'Everyman'.[66] Rex died in 2019 but older Kropotkins are still published.

- Ottawa Citizen

- The Ottawa Citizen has carried a weekly puzzle by Susannah Sears since 2001.

- Sydney Daily Telegraph

- Prints the "Stickler" puzzle, set by David Stickley.

- Sydney Morning Herald and The Age (Australia)

- Fairfax Media papers, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, print a daily puzzle, which was also available free on-line until 31 August 2009. Various compilers (setters) compose the puzzles, each being indicated by their initials. As of November 2013, compilers from Monday to Saturday include LR (Liam Runnalls), RM (Rose McGinley), DP (David Plomley), DH (Donald Harrison), NS (Nancy Sibtain), DA (David Astle), and DS (David Sutton).

- The Toronto Star (Canada)

- Includes a cryptic crossword from the Sunday Times in the Saturday edition in the Puzzles section. Friday and Sunday papers each have a different cryptic by Caroline Andrews.

- The Wall Street Journal (US)

- Starting in January 2010, The Wall Street Journal publishes a variety cryptic by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon every four weeks.[10]

Setters on more than one British national paper

[edit]Several setters appear in more than one paper. Some of these, with pseudonyms shown, are:

| Guardian | Times | Independent | Financial Times | Daily/Sunday Telegraph | Telegraph Toughie | Private Eye | Observer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paul Bringloe | x | Tees | Neo | |||||

| Michael Curl | Orlando | x | Cincinnus | |||||

| John Dawson | Chifonie | Armonie | ||||||

| John Galbraith Graham | Araucaria | Cinephile | ||||||

| Brian Greer | Brendan | x | Virgilius | x | Jed | |||

| Dave Gorman | Fed | Bluth | Django | |||||

| John Halpern | Paul | x | Punk | Mudd | Dada | |||

| Sarah Hayes | Arachne | x | Anarche | Rosa Klebb | ||||

| John Henderson | Enigmatist | x | Nimrod | Io | Elgar | |||

| Paul Henderson | Phi | Kcit | ||||||

| Margaret Irvine | Nutmeg | x | ||||||

| Eddie James[67] | Brummie | Cyclops | ||||||

| Mark Kelmanson | Monk | Monk | ||||||

| Don Manley | Pasquale | x | Quixote | Bradman | x | Giovanni | ||

| Philip Marlow | Hypnos | Sleuth | x | Shamus | ||||

| Dean Mayer | x | Anax | Loroso | Elkamere | ||||

| Roger Phillips | x | Nestor | Notabilis | |||||

| Richard Rogan | x | Bannsider | ||||||

| Allan Scott | x | Falcon | Campbell | Everyman | ||||

| Roger Squires | Rufus | Dante | x | |||||

| Neil Walker | Tramp | Jambazi | ||||||

| Mike Warburton | Scorpion | Aardvark | Osmosis | |||||

| John Young | Shed | Dogberry |

x – Denotes a compiler operating without a pseudonym in this publication.

In addition, Roger Squires compiles for the Glasgow Herald and the Yorkshire Post.

Roger Squires and the late Ruth Crisp set at various times in their careers for all 5 of the broadsheets.

Cryptic crossword research

[edit]Research into cryptic crossword solving has been comparatively sparse. Several discrete areas have been explored: the cognitive or linguistic challenges posed by cryptic clues;[68][69][70][71] the mechanisms by which the "Aha!" moment is triggered by solving cryptic crossword clues;[72] the use of cryptic crosswords to preserve cognitive flexibility ("use-it-or-lose-it") in aging populations;[68][73][74] and expertise studies into the drivers of high performance and ability in solving cryptics.[75][76][77]

Recent expertise studies by Friedlander and Fine, based on a large-scale survey of 805 solvers of all ability (mainly UK-based), suggest that cryptic crossword solvers are generally highly academically able adults whose education and occupations lie predominantly in the area of scientific, mathematical or IT-related fields. This STEM connection increases significantly with level of expertise, particularly for mathematics and IT. The authors suggest that cryptic crossword skill is bound up with code-cracking and problem-solving skills of a logical and quasi-algebraic nature.[77][78]

Friedlander and Fine also note that solvers are motivated predominantly by "Aha!" moments, and intrinsic rewards such as mental challenge. Solvers voluntarily choose to engage with intellectually and culturally stimulating activities like music, theatre, reading, and the arts in their leisure time, and pursue active musical participation such as singing or playing an instrument at noticeably higher levels than the UK national average.[77] Solving cryptic crossword clues can lead to a succession of 'Aha!' or 'Penny-Dropping' Moments which is highly rewarding;[79] Friedlander and Fine suggest that research could take advantage of the range of cryptic crossword devices to explore the mechanics of insight in more depth.[72] Looking at expert cryptic crossword solvers – who speedily overcome the clue misdirection – and comparing them with typical, everyday solvers of equal experience may provide a better understanding of the kind of person who can overcome a solving 'hitch' more easily, and how they go about it.

Cryptic crosswords in fiction

[edit]Cryptic crosswords often appear in British literature, and are particularly popular in murder mysteries, where they are part of the puzzle. The character Inspector Morse created by Colin Dexter is fond of solving cryptic crosswords, and the crosswords often become part of the mystery. Colin Dexter himself set crosswords for The Oxford Times for many years and was a national crossword champion.[80] In the short story "The Fascinating Problem of Uncle Meleager's Will", by Dorothy L Sayers, Lord Peter Wimsey solves a crossword in order to solve the mystery,[81] while the solution to Agatha Christie's Curtain hinges on an Othello themed crossword.[82] Ruth Rendell has used the device in her novel One Across, Two Down.[83] Among non-crime writers, crosswords often feature in the works of P. G. Wodehouse, and are an important part of the short story "The Truth About George".[84] Alan Plater's 1994 novel Oliver's Travels (turned into a BBC television serial of the same name in 1995) centres round crossword solving and the hunt for a missing compiler.[85]

Crosswords feature prominently in the 1945 British romantic drama film Brief Encounter,[86] scripted by playwright Noël Coward, which is number two in the British Film Institute's Top 100 British films. The plot of "The Riddle of the Sphinx", a 2017 episode of Inside No. 9, revolves around the clues and answers to a particular crossword puzzle, which had appeared on the day of the original broadcast in The Guardian.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For example, the two-word phrase hooded sweatshirt can mean the kind of garment that is usually called a hoodie. When a garment is described as a hooded sweatshirt, the -ed suffix of the word hooded means that the sweatshirt is 'equipped with a hood'.

- ^ Anagram indicators, among the thousands possible, include: about, abstract, absurd, adapted, adjusted, again, alien, alternative, anew, another, around, arranged, assembled, assorted, at sea, awful, awkward, bad, barmy, becomes, bizarre, blend, blow, break, brew, build, careless, changed, chaotic, characters, clumsy, composed, confused, contrived, convert, cooked, corrupt, could be, crazy, damaged, dancing, designed, develop, different, disorderly, disturbed, doctor, eccentric, edited, engineer, fabricate, fake, fancy, faulty, fiddled, fix, foolish, form, free, fudge, gives, ground, hammer, haywire, hybrid, improper, in a tizzy, involved, irregular, jostle, jumbled, jumping, kind of, knead, letters, loose, made, managed, maybe, messy, mistaken, mix, modified, moving, muddled, mutant, new, novel, odd, off, order, organised, otherwise, out, outrageous, peculiar, perhaps, playing, poor, possible, prepared, produced, queer, questionable, random, reform, remodel, repair, resort, rough, shaken, shifting, silly, sloppy, smashed, somehow, sort, spoilt, strange, style, switch, tangled, treated, tricky, troubled, turning, twist, unconventional, undone, unsettled, unsound, untidy, unusual, upset, used, vary, version, warped, wayward, weird, wild, working, wrecked and wrong.

- ^ A minor exception to this general rule is that simple abbreviations are sometimes used to add variety or challenge. For example, "Husband, a most eccentric fellow (6)" for THOMAS, where the anagram is made from A MOST plus H for husband.

- ^ The 's in the clue appears to indicate a possessive in the surface reading, but serves as a contraction for the link word is when read cryptically.

- ^ In another context "sweetheart" could itself be parsed to yield WEE or the letter E, i.e. the heart (middle) of sweet.

- ^ A complication in this clue is that "damaged" often (but not here) indicates an anagram. Similarly, "found" provides a misdirection in that it might itself indicate hidden words elsewhere.

References

[edit]- ^ Eliot, George. "Brief History of Crossword Puzzles". American Crossword Puzzle Tournament. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Cox & Rathvon (1995), pp. 8.

- ^ Millington, Roger. "The Strange World of the Crossword (excerpt)". Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Stephenson, Hugh (16 April 2015). "The story of how cryptic crosswords crossed the Atlantic". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (16 September 2011). "This Time It's Crosswords (Not Cross Words) That Surface From Sondheim". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Pender, Rick (2021). "Puzzles, Games, and Mysteries". The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 423–425. ISBN 9781538115862.

- ^ Reissued Aug 2001: Swallowtail Books ISBN 1-903400-04-X, ISBN 978-1-903400-04-3

- ^ How to master the Times Crossword, Tim Moorey, p. 186

- ^ Remnick, David. "Introducing The New Yorker Crossword Puzzle". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ a b Shenk, Mike (2020). Foreword. Blue-Chip Cryptic Crosswords: As Published in The Wall Street Journal. By Cox, Emily; Rathvon, Henry. New York: Puzzlewright. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4549-3621-3.

- ^ a b Gold, Hayley (September 2022). "Cryp-Tic Tick Tick Boom". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 46, no. 7. pp. 34–37. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Macnutt, Derrick (2001). Ximenes on the Art of the Crossword. London: Swallowtail Books. pp. 42–53. ISBN 1-903400-04-X.

- ^ "Cryptic crossword abbreviations". Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ Tossman, David (23 November 2013). "Crossword 847 answers and explanations". New Zealand Listener. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "One of Dr Ghil'ad Zuckermann's Cryptic Crosswords". Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- ^ "Tenglish crossword". Crossword Unclued, 29 September 2012. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Kannada crosswords: Prajavani, Udayavani, Kannada Prabha". Crossword Unclued, 22 August 2012. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Prize Hindi Puzzle: Here's Our Winner". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Dario De Toffoli (22 July 2015). "Il cruciverba più difficile del mondo". Il Fatto Quotidiano. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Parr, Andrew (September 2021). "Cryptic Classroom #1: Anagrams". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 45, no. 7. p. 33. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Parr, Andrew (January 2022). "Cryptic Classroom #4: Charades". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 46, no. 1. p. 33. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Parr, Andrew (April 2022). "Cryptic Classroom #6: Containers". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 46, no. 3. p. 33. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ a b c Parr, Andrew (May 2022). "Cryptic Classroom #7: Deletions, Reversals, & lit". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 46, no. 4. p. 33. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Parr, Andrew (October 2021). "Cryptic Classroom #2: Double Definitions". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 45, no. 8. p. 33. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Arachne (30 January 2014), Cryptic crossword No 26,170 Archived 3 July 2024 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian

- ^ Parr, Andrew (December 2021). "Cryptic Classroom #3: Hidden Words". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 45, no. 9. p. 33. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Parr, Andrew (February 2022). "Cryptic Classroom #5: Homophones". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 46, no. 2. p. 33. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Cox & Rathvon (1995), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Kosman, Joshua; Picciotto, Henri (4 October 2018). "Puzzle No. 3478". The Nation. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Kosman, Joshua; Picciotto, Henri (14 February 2013). "Going to the Bank". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Sutherland (2012), p. 117.

- ^ Cox & Rathvon (1995), pp. 63–64.

- ^ Henderson, John (24 April 2013). "(Enigmatist)". Cryptic crossword No 25,930. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Cox & Rathvon (1995), pp. 50–51.

- ^ manehi (1 August 2022). "Guardian Cryptic 28,824 by Vulcan". Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Reverse Anagrams". Crossword Unclued. 17 June 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ Vulcan (1 August 2022). "Cryptic crossword No 28,824". London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ a b Cox & Rathvon (1995), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Macnutt (1966), p. 73.

- ^ Phi (30 July 2021). "Cryptic Crossword No. 10,857". The Independent.

- ^ RatkojaRiku (30 July 2021). "Independent 10,857 / Phi". Fifteensquared. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Cryptic crossword No. 27,470". Daily Telegraph. 22 April 2014.

- ^ Gazza (22 April 2014). "DT 27470". Big Dave's Crossword Blog. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Parr, Andrew (June 2022). "Cryptic Classroom #8: Combination Clues". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 46, no. 5. pp. 38–39. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ Stigger, Bob (June 2019). "Trash Talk". GAMES–World of Puzzles. Vol. 43, no. 5. p. 62. ISSN 1074-4355.

- ^ A Display of Lights (9), Val Gilbert, 2008 - p. 155

- ^ Connor, Alan (4 December 2023). "Crossword blog: time to take stock". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ The Sunday Times Mephisto Crossword Book 1, 2003 - Introduction

- ^ Kamm, Oliver (26 March 2009). "The Times crossword the man who began it all". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Rogan, Richard (14 August 2023). "Times crosswords: introducing the new Quick Cryptic". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "The Times Crosswords". bestforpuzzles.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "The Bugle Audio Crossword". The Times UK. Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Horne, Jim (8 November 2008). "Acrostic Creators". Wordplay: The Crossword Blog of The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ Rathvon, Henry; Cox, Emily (13 August 2009). "The Puzzler: Sections". The Atlantic. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Cox & Rathvon (1995), p. 263.

- ^ Cox & Rathvon (1995), p. 264.

- ^ "THE HINDU CROSSWORD CORNER: THC Setters". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "Remembering Admiral Katari, the first crossword setter of The Hindu". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Gillespie, Elgy (22 October 2011). "Carrying the Crosaire". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Kosman, Joshua; Picciotto, Henri (19 March 2020). "No Cross Words". The Nation. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Birnholz, Evan (3 May 2020). "Solution to Evan Birnholz's May 3 Post Magazine crossword, "Disbanded"". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Simpson, Fraser, ed. (2001). 101 Cryptic Crosswords: From The New Yorker. New York: Sterling. ISBN 0-8069-0186-1.

- ^ Henriquez, Nicholas; Maynes-Aminzade, Liz (26 November 2019). "Reintroducing The New Yorker's Cryptic Crossword". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Henriquez, Nicholas; Maynes-Aminzade, Liz; Kravis, Andy (27 June 2021). "Announcing an All-New Weekly Cryptic Crossword from The New Yorker". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Maynes-Aminzade, Liz (18 March 2024). "Introducing the New Yorker Mini Crossword". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 1 April 2024. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

We'll no longer publish a cryptic crossword on Sundays, but fans of the form can still access our archive of more than two hundred cryptics.

- ^ New Zealand Herald

- ^ https://archive.today/20120630225049/http://www.btinternet.com/~ed.xword/ EJ's Crossword Showcase

- ^ a b Forshaw, M., Expertise and Ageing: The Crossword Puzzle Paradigm, PhD thesis. 1994, University of Manchester.

- ^ Schulman, A., The Art of the Puzzler, in Cognitive Ecology: Handbook of Perception and Cognition, M.P. Friedman and E.C. Carterette, Editors. 1996, Academic Press: San Diego, CA. p. 293-321.

- ^ Aarons, D., Jokes and the Linguistic Mind. Introduction to linguistics/cognitive science. 2012, London: Routledge.

- ^ Aarons, D.L. (2015). "Following Orders: Playing Fast and Loose with Language and Letters". Australian Journal of Linguistics. 35 (4): 351–380. doi:10.1080/07268602.2015.1068459. S2CID 60466349.

- ^ a b Friedlander, Kathryn J.; Fine, Philip A. (2018). ""The Penny Drops": Investigating Insight Through the Medium of Cryptic Crosswords". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 904. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00904. PMC 6037892. PMID 30018576.

- ^ Winder, B.C., Intelligence and expertise in the elderly, PhD thesis 1993, University of Manchester: UK.

- ^ Almond, N.M., Use-it-or-lose-it: Investigating the cognitive reserve hypothesis and use-dependency theory, PhD thesis. 2010, Leeds.

- ^ Underwood, G., J. MacKeith, and J. Everatt, Individual differences in reading skill and lexical memory: the case of the crossword puzzle expert, in Practical aspects of memory: current research and issues, M.M. Gruneberg, P.E. Morris, and R.N. Sykes, Editors. 1988, Wiley: Chichester. p. 301-308.

- ^ Underwood, G.; Deihim, C.; Batt, V. (1994). "Expert performance in solving word puzzles: from retrieval cues to crossword clues". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 8 (6): 531–548. doi:10.1002/acp.2350080602.

- ^ a b c Friedlander, K.J.; Fine, P.A. (2016). "The Grounded Expertise Components Approach in the novel area of cryptic crossword solving". Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 567. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00567. PMC 4853387. PMID 27199805.

- ^ "What makes an expert cryptic crossword solver?". CREATE Ψ. 19 December 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ "Are cryptic crosswords really 'better than sex'?". CREATE Ψ. 3 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Chambers Book of "Morse" Crosswords: Amazon.co.uk: Don Manley, Colin Dexter: 9780550102799: Books. ASIN 0550102795.

- ^ Alan Connor (23 August 2012). "Top 10 crosswords in fiction, no 2: Lord Peter Wimsey". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2016.