Aliyah

| Part of a series on |

| Aliyah |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

| Pre-Modern Aliyah |

| Aliyah in modern times |

| Absorption |

| Organizations |

| Related topics |

Aliyah (US: /ˌæliˈɑː/, UK: /ˌɑː-/; Hebrew: עֲלִיָּה ʿălīyyā, lit. 'ascent') is the immigration of Jews from the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the State of Israel. Traditionally described as "the act of going up" (towards the Jewish holy city of Jerusalem), moving to the Land of Israel or "making aliyah" is one of the most basic tenets of Zionism. The opposite action – emigration by Jews from the Land of Israel – is referred to in the Hebrew language as yerida (lit. 'descent').[1] The Law of Return that was passed by the Israeli parliament in 1950 gives all diaspora Jews, as well as their children and grandchildren, the right to relocate to Israel and acquire Israeli citizenship on the basis of connecting to their Jewish identity.

For much of their history, most Jews have lived in the diaspora outside of the Land of Israel due to various historical conflicts that led to their persecution alongside multiple instances of expulsions and exoduses. In the late 19th century, 99.7% of the world's Jews lived outside the region, with Jews representing 2–5% of the population of the Palestine region.[2][3] Despite its historical value as a national aspiration for the Jewish people, aliyah was acted upon by few prior to the rise of a national awakening among Jews worldwide and the subsequent development of the Zionist movement in the late 19th century;[4] the large-scale immigration of Jews to Palestine had consequently begun by 1882.[5] Since the Israeli Declaration of Independence in 1948, more than 3 million Jews have made aliyah.[6] As of 2014[update], Israel and the Israeli-occupied territories contain approximately 42.9 percent of the world's Jewish population.[7]

Terminology

The Hebrew word aliyah means "ascent" or "going up". Jewish tradition views traveling to the Land of Israel as an ascent, both geographically and metaphysically. In one opinion, the geographical sense preceded the metaphorical one, as most Jews going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, which is situated at approximately 750 meters (2,500 feet) above sea level, had to climb to a higher geographic elevation. The reason is that many Jews in early rabbinic times used to live either in Egypt's Nile Delta and on the plains of Babylonia, which lay relatively low; or somewhere in the Mediterranean Basin, from where they arrived by ship.[8]

It is noteworthy that various references in the earlier books of the Bible indicate that Egypt was considered as being "below" other countries, so that going to Egypt was described as "going down to Egypt" while going away from Egypt (including Hebrews going out of Egypt to Canaan) was "going up out of Egypt". Thus, in the Book of Genesis 46 God speaks to Jacob and says “Do not be afraid to go down to Egypt, for I will make you into a great nation there. I will go down to Egypt with you." And in the Book of Exodus 1, the oppressive new King of Egypt suspects the Hebrews of living in Egypt of being enemies who in time of war might "Fight against us, and so get them up out of the land".

Widespread use of the term Aliyah to describe ideologically inspired Jewish immigration to Palestine / Israel is due to Arthur Ruppin's 1930 work Soziologie der Juden.[9] Aliyah has also been defined, by sociologists such as Aryeh Tartakower, as immigration for the good of the community, regardless of the destination.[10]

Aliyah is an important Jewish cultural concept and a fundamental component of Zionism. It is enshrined in Israel's Law of Return, which accords any Jew (deemed as such by halakha and/or Israeli secular law) and eligible non-Jews (a child and a grandchild of a Jew, the spouse of a Jew, the spouse of a child of a Jew and the spouse of a grandchild of a Jew), the legal right to assisted immigration and settlement in Israel, as well as Israeli citizenship. Someone who "makes aliyah" is called an oleh (m.; pl. olim) or olah (f.; pl. olot). Many religious Jews espouse aliyah as a return to the Promised Land, and regard it as the fulfillment of God's biblical promise to the descendants of the Hebrew patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Nachmanides (the Ramban) includes making aliyah in his enumeration of the 613 commandments.[11]

Sifre says that the mitzvah (commandment) of living in Eretz Yisrael is as important as all the other mitzvot put together. There are many mitzvot such as shmita, the sabbatical year for farming, which can only be performed in Israel.[12]

For generations of religious Jews, aliyah was associated with the coming of the Jewish Messiah. Jews prayed for their Messiah to come, who was to redeem the "Land of Israel" (Eretz Yisrael, commonly known in English as the region of Palestine) from gentile rule and return world Jewry to the land under a Halachic theocracy.[13]

In Zionist discourse, the term aliyah (plural aliyot) includes both voluntary immigration for ideological, emotional, or practical reasons and, on the other hand, mass flight of persecuted populations of Jews. The vast majority of Israeli Jews today trace their family's recent roots to outside the country. While many have actively chosen to settle in Israel rather than some other country, many had little or no choice about leaving their previous home countries.[citation needed] While Israel is commonly recognized as "a country of immigrants", it is also, in large measure, a country of refugees, including internal refugees. Israeli citizens who marry individuals of Palestinian heritage, born within the Israeli-occupied territories and carrying Palestinian IDs, must renounce Israeli residency themselves in order to live and travel together with their spouses.[14]

Pre-modern aliyah

Biblical

The Hebrew Bible relates that the patriarch Abraham came to the Land of Canaan with his family and followers in approximately 1800 BC. His grandson Jacob went down to Egypt with his family, and after several centuries there, the Israelites went back to Canaan under Moses and Joshua, entering it in about 1300 BC.[citation needed]

Antiquity

In Zionist historiography, post the Balfour Declaration and the start of the "Third Aliyah", the "First Aliyah" and "Second Aliyah" originally referred to the two Biblical "returns to Zion" described in Ezra–Nehemiah – the "First Aliya" led by Zerubbabel, and the "Second Aliya" led by Ezra and Nehemiah approximately 80 years later.[15] A few decades after the fall of the Kingdom of Judah and the Babylonian exile of the Jewish people, approximately 50,000 Jews returned to Zion following the Cyrus Declaration from 538 BC. The Jewish priestly scribe Ezra led the Jewish exiles living in Babylon to their home city of Jerusalem in 459 BC. Even those Jews who did not end up returning gave their children names like Yashuv-Tzadik and Yaeliyahu which testified to their desire to return.[16]

Jews returned to the Land of Israel throughout the Second Temple period. Herod the Great also encouraged aliyah and often gave key posts, such as the position of High Priest, to returnees.[17]

In late antiquity, the two hubs of rabbinic learning were Babylonia and the land of Israel. Throughout the Amoraic period, many Babylonian Jews immigrated to the land of Israel and left their mark on life there, as rabbis and leaders.[18]

Middle Ages

In the 10th century, leaders of the Karaite Jewish community, mostly living under Persian rule, urged their followers to settle in Eretz Yisrael. The Karaites established their own quarter in Jerusalem, on the western slope of the Kidron Valley. During this period, there is abundant evidence of pilgrimages to Jerusalem by Jews from various countries, mainly in the month of Tishrei, around the time of the Sukkot holiday.[19]

The number of Jews migrating to the land of Israel rose significantly between the 13th and 19th centuries, mainly due to a general decline in the status of Jews across Europe and an increase in religious persecution. The expulsion of Jews from England (1290), France (1391), Austria (1421), and Spain (the Alhambra decree of 1492) were seen by many as a sign of approaching redemption and contributed greatly to the messianic spirit of the time.[20]

Aliyah was also spurred during this period by the resurgence of messianic fervor among the Jews of France, Italy, the Germanic states, Poland, Russia, and North Africa. The belief in the imminent coming of the Jewish Messiah, the ingathering of the exiles and the re-establishment of the kingdom of Israel encouraged many who had few other options to make the perilous journey to the land of Israel.[citation needed]

Pre-Zionist resettlement in Palestine met with various degrees of success. In 1211, the "aliyah of the three hundred rabbis" saw notable French and German Tosafists such as Samson of Coucy, Joseph ben Baruch, Baruch ben Isaac and Samson ben Abraham of Sens, along with their colleagues and students, emigrate to Palestine, as recorded in the Shebet Yehudah. There is doubt about the accuracy of the account, as there is no evidence that there were actually 300 immigrants, and that number is likely exaggerated. It also mentions Jonathan ben David ha-Cohen emigrating there, but he died in 1205, and was said to have celebrated Purim in Palestine in 1210.[21][22] Little is known of the fate of their descendants. It is thought that few survived the bloody upheavals caused by the Crusader invasion in 1229 and their subsequent expulsion by the Muslims in 1291. After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 and the expulsion of Jews from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1498), many Jews made their way to the Holy Land.[23][24]

Samson b. Abraham of Sens, who emigrated in 1211, wrote in his responsa that the biblical commandment to go to Eretz Yisrael was nullified due to pikuach nefesh, or saving a life, citing the danger of the journey, particularly for pregnant women. Haim ben Hananel HaCohen ruled that the commandment was negated altogether. Moses ben Joseph di Trani, born in Salonika in 1490, made aliyah and became the rabbi of Safed, where he died in 1580. In his writings, Trani disagreed with Haim Cohen, and argued that it was not dangerous to travel to Palestine due to the peace between "Edom" (Christian Europe) and "Ishmael" (Islamic/Arab world) at the time. David ibn Zimri, known as the Radbaz, also went to Palestine where he died in 1574.[25] The Radbaz reconciled Maimonides' brief journey to Jerusalem in 1165, but ultimate settlement in Egypt, despite Maimonides' belief that it was commanded to settle in Eretz Yisrael and forbidden to remain in Egypt, that he had been compelled to remain by the authorities, as physician to the sultan. Ishtori Haparchi, who was a geographer of Palestine, said that Maimonides signed letters as "the writer who transgresses three negative commandments every day," though no surviving responsa with Maimonides' autograph are found bearing this.[25][26]

Notable rabbi Nahmanides went to Jerusalem a few years before his death in 1267.[27] Isaiah Horowitz made aliyah in 1621.[28] Nahmanides, in his gloss on Maimonides' Book of Commandments, articulated that contrary to Rashi's interpretation, settling Eretz Yisrael was a divine commandment and not simply a promise, arguing that the Torah commanded the people of Israel to conquer and possess the Holy Land. Though he spent most of his life in Gerona, he went to Palestine without his wife and children and died in 1270. It not known why his family did not join him.[25]

In 1541, following their expulsion from Naples, some Jews emigrated to Palestine. In the 1560s, Gracia Mendes and Joseph Nasi obtained a concession from the sultan to permit Jews to settle in Safed and Tiberias.[29][30]

Some Ukrainian Jewish refugees fleeing the pogroms of the Khmelnytsky Uprising of the mid-17th century also settled in the Holy Land. Then the immigration in the 18th and early 19th centuries of thousands of followers of various Kabbalist and Hassidic rabbis, as well as the disciples of the Vilna Gaon and the disciples of the Chattam Sofer, added considerably to the Jewish populations in Jerusalem, Tiberias, Hebron, and Safed.[citation needed]

18th century

The 1700 immigration associated with messianic Sabbateanism is considered the first modern mass movement of Jewish immigrants to Israel.[31] Also in 1700, Judah HeHasid and his followers settled in Jerusalem, and Hayyim ben Jacob Abulafia and his followers in Tiberias.[32] HeHasid's Hurva Synagogue (or "ruined synagogue"), rebuilt on the ruins of a 15th century synagogue, was again destroyed in 1720.[28]

A notable emigration of about 300 Hasidic immigrants led by Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk and Abraham Kalisker in 1777 aimed to establish a religious center. They were preceded by Nachman of Horodenka, Abraham Gershon of Kitov and Menahem Mendel of Premyshlan in 1764, members of the circle of the Baal Shem Tov.[33]

19th century

The messianic dreams of the Gaon of Vilna inspired one of the largest pre-Zionist waves of immigration to Eretz Yisrael. In 1808 hundreds of the Gaon's disciples, known as Perushim, settled in Tiberias and Safed, and later formed the core of the Old Yishuv in Jerusalem.[34] This was part of a larger movement of thousands of Jews from countries as widely spaced as Persia and Morocco, Yemen and Russia, who moved to Palestine beginning in the first decade of the nineteenth century – and in even larger numbers after the conquest of the region by Muhammad Ali of Egypt in 1832 – all drawn by the expectation of the arrival of the Messiah in the Jewish year 5600, Christian year 1840, a movement documented in Arie Morgenstern's Hastening Redemption.[35] There were also those who like the British mystic Laurence Oliphant tried to lease Northern Palestine to settle the Jews there (1879).[citation needed]

Jewish immigration to Palestine began in earnest following the 1839 Tanzimat reforms; between 1840 and 1880, the Jewish population of Palestine rose from 9,000 to 23,000.[a]

Zionist aliyah (19th c.)

In Zionist history, the different waves of aliyah, beginning with the arrival of the Biluim from Russia in 1882, are categorized by date and the country of origin of the immigrants. In 1872 colonies were established at Petah Tikva and Rosh Pinna. Jewish settlement in Jaffa may be dated to 1820, when Isaiah Ajiman moved there from Istanbul. Mikveh Israel agricultural school was established in 1870.[32] Ajiman, a merchant, was executed in 1826, marking a decline in the status of Ottoman Jews.[37]

In the late 19th century, 99.7% of the world's Jews lived outside the region, with Jews representing 2–5% of the population of the Palestine region.[2][3]

Pre-19th century small-scale return migration of Diaspora Jews to the Land of Israel is characterized as the Pre-Modern Aliyah. Since the birth of Zionism in the late 19th century, the advocates of aliyah have striven to facilitate the settlement of Jewish refugees in Ottoman Palestine, Mandatory Palestine, and the sovereign State of Israel.

The periodization of historical waves of Aliyah was first published after the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which created expectations of the start of a huge wave of immigration dubbed the "Third Aliyah", in contrast to the Biblical "First Aliyah" and "Second Aliyah" "returns to Zion" described in Ezra–Nehemiah.[38] Over the next two years, discussion in Zionist literature transformed the two prior to refer to the contemporary immigration waves at the end of the 19th century and the early 20th. These periods as per the modern convention were first published in October 1919 by Yosef Haim Brenner.[39]

In the 1930s and 1940s, Zionist historians began to divide the next periods of immigration to Palestine into different phases, in a form which "created and presumed the unique traits of aliyah and the Zionist enterprise".[40] The currently accepted five-wave periodization was first published in Hebrew by sociologist David Gurevich in his 1944 work The Jewish Population of Palestine: Immigration, Demographic Structure and Natural Growth:[41] the First Aliyah and the Second Aliyah to Ottoman Palestine, followed by the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Aliyah to Mandatory Palestine.[41] Following Ruppin and Jacob Lestschinsky before him, Gurevich's use of the term Aliyah emphasized the ideological element of the immigration,[42] despite the fact that such a motivation was not representative of the immigrants as a whole.[41]

Subsequently, named periods include Aliyah Bet (immigration done in spite of restrictive Mandatory law) between 1934 and 1948 and the Bricha of the Holocaust survivors; the aliyah from elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa as well as the aliyah from Western and Communist countries following the Six-Day War with the 1968 Polish political crisis, as well as the aliyah from post-Soviet states in the 1990s. Today, most aliyah consists of voluntary migration for ideological, economic, or family reunification purposes. Because Jewish lineage can provide a right to Israeli citizenship, aliyah (returning to Israel) has both a secular and a religious significance.[citation needed]

The first modern period of immigration to receive a number in common speech was the Third Aliyah, which in the World War I period was referred to as the successor to the First and Second Aliyot from Babylonia in the Biblical period. Reference to earlier modern periods as the First and Second Aliyot appeared first in 1919 and took a while to catch on.[43]

Ottoman Palestine (1881–1914)

The pronounced persecution of Russian Jews between 1881 and 1910 led to a large wave of emigration.[44] Since only a small portion of East European Jews had adopted Zionism by then, between 1881 and 1914 only 30–40,000 emigrants went to Ottoman Palestine, while over one and a half million Russian Jews and 300,000 from Austria-Hungary reached Northern America.[44]

First Aliyah (1882–1903)

Between 1882 and 1903, approximately 35,000 Jews immigrated to the Ottoman Palestine, joining the pre-existing Jewish population which in 1880 numbered 20,000-25,000. The Jews immigrating arrived in groups that had been assembled, or recruited. Most of these groups had been arranged in the areas of Romania and Russia in the 1880s. The migration of Jews from Russia correlates with the end of the Russian pogroms, with about 3 percent of Jews emigrating from Europe to Palestine. The groups who arrived in Palestine around this time were called Hibbat Tsiyon, which is a Hebrew word meaning "fondness for Zion." They were also called Hovevei Tsiyon or "enthusiasts for Zion" by the members of the groups themselves. While these groups expressed interest and "fondness" for Palestine, they were not strong enough in number to encompass an entire mass movement as would appear later on in other waves of migration.[45] The majority, belonging to the Hovevei Zion and Bilu movements, came from the Russian Empire with a smaller number arriving from Yemen. Many established agricultural communities. Among the towns that these individuals established are Petah Tikva (already in 1878), Rishon LeZion, Rosh Pinna, and Zikhron Ya'akov. In 1882 the Yemenite Jews settled in the Arab village of Silwan located south-east of the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem on the slopes of the Mount of Olives.[46] Kurdish Jews settled in Jerusalem starting around 1895.[47]

Second Aliyah (1904–1914)

Between 1904 and 1914, 35–40,000 Jews immigrated to Ottoman Palestine. The vast majority came from the Russian Empire, in particular from the Pale of Settlement in Eastern Europe. Jews from other countries in Eastern Europe such as Romania and Bulgaria also joined. Jewish emigration from Eastern Europe was largely due to pogroms and outbreaks of anti-Semitism there. However, Mountain Jews from the Caucasus and Jews from other countries including Yemen, Iran, and Argentina also arrived at this time. The Eastern European Jewish immigrants of this period, greatly influenced by socialist ideals, established the first kibbutz, Degania Alef, in 1909 and formed self-defense organizations, such as Hashomer, to counter increasing Arab hostility and to help Jews to protect their communities from Arab marauders.[48] Ahuzat Bayit, a new suburb of Jaffa established in 1909, eventually grew to become the city of Tel Aviv. During this period, some of the underpinnings of an independent nation-state arose: Hebrew, the ancient national language, was revived as a spoken language; newspapers and literature written in Hebrew were published; political parties and workers organizations were established. The First World War effectively ended the period of the Second Aliyah. It is estimated that over half of those who arrived during this period ended up leaving; Ben Gurion stated that nine out of ten left.[49]

British Palestine (1919–1948)

Third Aliyah (1919–1923)

Between 1919 and 1923, 40,000 Jews, mainly from Eastern Europe, arrived in the wake of World War I. The British occupation of Palestine and the establishment of the British Mandate created the conditions for the implementation of the promises contained in the Balfour Declaration. Many of the Jewish immigrants were ideologically driven pioneers, known as halutzim, trained in agriculture and capable of establishing self-sustaining economies. In spite of immigration quotas established by the British administration, the Jewish population reached 90,000 by the end of this period. The Jezreel Valley and the Hefer Plain marshes were drained and converted to agricultural use. Additional national institutions arose such as the Histadrut (General Labor Federation); an elected assembly; national council; and the Haganah, the forerunner of the Israel Defense Forces.[citation needed]

Fourth Aliyah (1924–1929)

Between 1924 and 1929, 82,000 Jews arrived, many as a result of increasing anti-Semitism in Poland and throughout Europe. The vast majority of Jewish immigrants arrived from Europe mostly from Poland, the Soviet Union, Romania, and Lithuania, but about 12% came from Asia, mostly Yemen and Iraq. The immigration quotas of the United States kept Jews out. This group contained many middle-class families that moved to the growing towns, establishing small businesses, and light industry. Of these approximately 23,000 left the country.[50]

Fifth Aliyah (1929–1939)

Between 1929 and 1939, with the rise of Nazism in Germany, a new wave of 250,000 immigrants arrived; the majority of these, 174,000, arrived between 1933 and 1936, after which increasing restrictions on immigration by the British made immigration clandestine and illegal, called Aliyah Bet. The Fifth Aliyah was again driven almost entirely from Europe, mostly from Central Europe (particularly from Poland, Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia), but also from Greece. Some Jewish immigrants also came from other countries such as Turkey, Iran, and Yemen. The Fifth Aliyah contained large numbers of professionals, doctors, lawyers, and professors, from Germany. Refugee architects and musicians introduced the Bauhaus style (the White City of Tel Aviv has the highest concentration of International Style architecture in the world with a strong element of Bauhaus) and founded the Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra. With the completion of the port at Haifa and its oil refineries, significant industry was added to the predominantly agricultural economy. The Jewish population reached 450,000 by 1940.[citation needed]

At the same time, tensions between Arabs and Jews grew during this period, leading to a series of Arab riots against the Jews in 1929 that left many dead and resulted in the depopulation of the Jewish community in Hebron. This was followed by more violence during the "Great Uprising" of 1936–1939. In response to the ever-increasing tension between the Arabic and Jewish communities married with the various commitments the British faced at the dawn of World War II, the British issued the White Paper of 1939, which severely restricted Jewish immigration to 75,000 people for five years. This served to create a relatively peaceful eight years in Palestine while the Holocaust unfolded in Europe.[citation needed]

Shortly after their rise to power, the Nazis negotiated the Ha'avara or "Transfer" Agreement with the Jewish Agency under which 50,000 German Jews and $100 million worth of their assets would be moved to Palestine.[51]

-

Survey of Palestine, showing place of origin of immigrants between 1922 and 1944

-

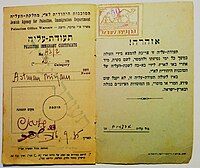

Certificate issued by the Jewish Agency in Warsaw, Poland, for immigrant to Mandatory Palestine, September 1935

Aliyah Bet: Illegal immigration (1933–1948)

The British government limited Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine with quotas, and following the rise of Nazism to power in Germany, illegal immigration to Mandatory Palestine commenced.[52] The illegal immigration was known as Aliyah Bet ("secondary immigration"), or Ha'apalah, and was organized by the Mossad Le'aliyah Bet, as well as by the Irgun. Immigration was done mainly by sea, and to a lesser extent overland through Iraq and Syria. During World War II and the years that followed until independence, Aliyah Bet became the main form of Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine.[citation needed]

Following the war, Bricha ("escape"), an organization of former partisans and ghetto fighters was primarily responsible for smuggling Jews from Eastern Europe through Poland. In 1946 Poland was the only Eastern Bloc country to allow free Jewish aliyah to Mandate Palestine without visas or exit permits.[53] By contrast, Stalin forcibly brought Soviet Jews back to USSR, as agreed by the Allies during the Yalta Conference.[54] The refugees were sent to the Italian ports from which they traveled to Mandatory Palestine. More than 4,500 survivors left the French port of Sète aboard President Warfield (renamed Exodus). The British turned them back to France from Haifa, and forced them ashore in Hamburg. Despite British efforts to curb the illegal immigration, during the 14 years of its operation, 110,000 Jews immigrated to Palestine. In 1945 reports of the Holocaust with its 6 million Jewish killed, caused many Jews in Palestine to turn openly against the British Mandate, and illegal immigration escalated rapidly as many Holocaust survivors joined the aliyah.[citation needed]

Early statehood (1948–1960)

| Immigration to Israel in the years following the May 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence.[55] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 1949 | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1948-53 | |

| Eastern Europe | |||||||

| Romania | 17678 | 13595 | 47041 | 40625 | 3712 | 61 | 122712 |

| Poland | 28788 | 47331 | 25071 | 2529 | 264 | 225 | 104208 |

| Bulgaria | 15091 | 20008 | 1000 | 1142 | 461 | 359 | 38061 |

| Czechoslovakia | 2115 | 15685 | 263 | 150 | 24 | 10 | 18247 |

| Hungary | 3463 | 6842 | 2302 | 1022 | 133 | 224 | 13986 |

| Soviet Union | 1175 | 3230 | 2618 | 689 | 198 | 216 | 8126 |

| Yugoslavia | 4126 | 2470 | 427 | 572 | 88 | 14 | 7697 |

| Total | 72436 | 109161 | 78722 | 46729 | 4880 | 1109 | 313037 |

| Other Europe | |||||||

| Germany | 1422 | 5329 | 1439 | 662 | 142 | 100 | 9094 |

| France | 640 | 1653 | 1165 | 548 | 227 | 117 | 4350 |

| Austria | 395 | 1618 | 746 | 233 | 76 | 45 | 3113 |

| United Kingdom | 501 | 756 | 581 | 302 | 233 | 140 | 2513 |

| Greece | 175 | 1364 | 343 | 122 | 46 | 71 | 2121 |

| Italy | 530 | 501 | 242 | 142 | 95 | 37 | 1547 |

| Netherlands | 188 | 367 | 265 | 282 | 112 | 95 | 1309 |

| Belgium | - | 615 | 297 | 196 | 51 | 44 | 1203 |

| Total | 3851 | 12203 | 5078 | 2487 | 982 | 649 | 25250 |

| Asia | |||||||

| Iraq | 15 | 1708 | 31627 | 88161 | 868 | 375 | 122754 |

| Yemen | 270 | 35422 | 9203 | 588 | 89 | 26 | 45598 |

| Turkey | 4362 | 26295 | 2323 | 1228 | 271 | 220 | 34699 |

| Iran | 43 | 1778 | 11935 | 11048 | 4856 | 1096 | 30756 |

| Aden | - | 2636 | 190 | 328 | 35 | 58 | 3247 |

| India | 12 | 856 | 1105 | 364 | 49 | 650 | 3036 |

| China | - | 644 | 1207 | 316 | 85 | 160 | 2412 |

| Other | - | 1966 | 931 | 634 | 230 | 197 | 3958 |

| Total | 4702 | 71305 | 58521 | 102667 | 6483 | 2782 | 246460 |

| Africa | |||||||

| Tunisia | 6821 | 17353 | 3725 | 3414 | 2548 | 606 | 34467 |

| Libya | 1064 | 14352 | 8818 | 6534 | 1146 | 224 | 32138 |

| Morocco | - | - | 4980 | 7770 | 5031 | 2990 | 20771 |

| Egypt | - | 7268 | 7154 | 2086 | 1251 | 1041 | 18800 |

| Algeria | - | - | 506 | 272 | 92 | 84 | 954 |

| South Africa | 178 | 217 | 154 | 35 | 11 | 33 | 628 |

| Other | - | 382 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 405 |

| Total | 8063 | 39572 | 25342 | 20117 | 10082 | 4987 | 108163 |

| Unknown | 13827 | 10942 | 1742 | 1901 | 948 | 820 | 30180 |

| All countries | 102879 | 243183 | 169405 | 173901 | 23375 | 10347 | 723090 |

After Aliyah Bet, the process of numbering or naming individual aliyot ceased, but immigration did not. A major wave of Jewish immigration, mainly from post-Holocaust Europe and the Arab and Muslim world took place from 1948 to 1951. In three and a half years, the Jewish population of Israel, which was 650,000 at the state's founding, was more than doubled by an influx of about 688,000 immigrants.[56] In 1949, the largest-ever number of Jewish immigrants in a single year—249,954—arrived in Israel.[6] This period of immigration is often termed kibbutz galuyot (literally, ingathering of exiles), due to the large number of Jewish diaspora communities that made aliyah. However, kibbutz galuyot can also refer to aliyah in general.[citation needed]

At the beginning of the immigration wave, most of the immigrants to reach Israel were Holocaust survivors from Europe, including many from displaced persons camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy, and from British detention camps on Cyprus. Large sections of shattered Jewish communities throughout Europe, such as those from Poland and Romania also immigrated to Israel, with some communities, such as those from Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, being almost entirely transferred. At the same time, the number of Jewish immigrants from Arab countries greatly increased. Special operations were undertaken to evacuate Jewish communities perceived to be in serious danger to Israel, such as Operation Magic Carpet, which evacuated almost the entire Jewish population of Yemen, and Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, which airlifted most of the Jews of Iraq to Israel.[56] Egyptian Jews were smuggled to Israel in Operation Goshen. Nearly the entire Jewish population of Libya left for Israel around this time, and clandestine aliyah from Syria took place, as the Syrian government prohibited Jewish emigration, in a process that was to last decades. Israel also saw significant immigration of Jews from non-Arab Muslim countries such as Iran, Turkey, and Afghanistan in this period.[citation needed]

This resulted in a period of austerity. To ensure that Israel, which at that time had a small economy and scant foreign currency reserves, could provide for the immigrants, a strict regime of rationing was put in place. Measures were enacted to ensure that all Israeli citizens had access to adequate food, housing, and clothing. Austerity was very restrictive until 1953; the previous year, Israel had signed a reparations agreement with West Germany, in which the West German government would pay Israel as compensation for the Holocaust, due to Israel's taking in a large number of Holocaust survivors. The resulting influx of foreign capital boosted the Israeli economy and allowed for the relaxing of most restrictions. The remaining austerity measures were gradually phased out throughout the following years.[citation needed] When new immigrants arrived in Israel, they were sprayed with DDT, underwent a medical examination, were inoculated against diseases, and were given food. The earliest immigrants received desirable homes in established urban areas, but most of the immigrants were then sent to transit camps, known initially as immigrant camps, and later as Ma'abarot. Many were also initially housed in reception centers in military barracks. By the end of 1950, some 93,000 immigrants were housed in 62 transit camps. The Israeli government's goal was to get the immigrants out of refugee housing and into society as speedily as possible. Immigrants who left the camps received a ration card, an identity card, a mattress, a pair of blankets, and $21 to $36 in cash. They settled either in established cities and towns, or in kibbutzim and moshavim.[56][57] Many others stayed in the Ma'abarot as they were gradually turned into permanent cities and towns, which became known as development towns, or were absorbed as neighborhoods of the towns they were attached to, and the tin dwellings were replaced with permanent housing.[citation needed]

In the early 1950s, the immigration wave subsided, and emigration increased; ultimately, some 10% of the immigrants would leave Israel for other countries in the following years. In 1953, immigration to Israel averaged 1,200 a month, while emigration averaged 700 a month. The end of the period of mass immigration gave Israel a critical opportunity to more rapidly absorb the immigrants still living in transit camps.[58] The Israeli government built 260 new settlements and 78,000 housing units to accommodate the immigrants, and by the mid-1950s, almost all were in permanent housing.[59] The last ma'abarot closed in 1963.

In the mid-1950s, a smaller wave of immigration began from North African countries such as Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt, many of which were in the midst of nationalist struggles. Between 1952 and 1964, some 240,000 North African Jews came to Israel. During this period, smaller but significant numbers arrived from other places such as Europe, Iran, India, and Latin America.[59] In particular, a small immigration wave from then communist Poland, known as the "Gomulka Aliyah", took place during this period. From 1956 to 1960, Poland permitted free Jewish emigration, and some 50,000 Polish Jews immigrated to Israel.[60]

Since the founding of the State of Israel, the Jewish Agency for Israel was mandated as the organization responsible for aliyah in the diaspora.[61]

From Arab countries

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish exodus from the Muslim world |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Antisemitism in the Arab world |

| Exodus by country |

| Remembrance |

| Related topics |

From 1948 until the early 1970s, around 900,000 Jews from Arab lands left, fled, or were expelled from various Arab nations, of which an estimated 650,000 settled in Israel.[62] In the course of Operation Magic Carpet (1949–1950), nearly the entire community of Yemenite Jews (about 49,000) immigrated to Israel. Its other name, Operation On Wings of Eagles (Hebrew: כנפי נשרים, Kanfei Nesharim), was inspired by

Exodus 19:4: "Ye have seen what I did unto the Egyptians, and how I bare you on eagles' wings, and brought you unto myself."[63]

and

Isaiah 40:31: "But they that wait upon the LORD shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint".[64]

Some 120,000 Iraqi Jews were airlifted to Israel in Operation Ezra and Nehemiah.

From Iran

Following the establishment of Israel, about one-third of Iranian Jews, most of them poor, immigrated to Israel, and immigration from Iran continued throughout the following decades. An estimated 70,000 Iranian Jews immigrated to Israel between 1948 and 1978. Following the Islamic Revolution in 1979, most of the Iranian Jewish community left, with some 20,000 Iranian Jews immigrating to Israel. Many Iranian Jews also settled in the United States (especially in New York City and Los Angeles).[65]

From Ethiopia

The first major wave of aliyah from Ethiopia took place in the mid-1970s. The massive airlift known as Operation Moses began to bring Ethiopian Jews to Israel on November 18, 1984, and ended on January 5, 1985. During those six weeks, some 6,500–8,000 Ethiopian Jews were flown from Sudan to Israel. An estimated 2,000–4,000 Jews died en route to Sudan or in Sudanese refugee camps. In 1991 Operation Solomon was launched to bring the Beta Israel Jews of Ethiopia. In one day, May 24, 34 aircraft landed at Addis Ababa and brought 14,325 Jews from Ethiopia to Israel. Since that time, Ethiopian Jews have continued to immigrate to Israel bringing the number of Ethiopian-Israelis today to over 100,000.[citation needed]

From Romania

After the war, Romania had second-largest Jewish population in Europe, of around 350,000 or higher. In 1949, 118,939 Romanian Jews had emigrated to Israel since the war ended.[66]

Romanian Jews were, under their own will, "sold" or "exchanged" to Israel in the 1950s with the help of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee for about 8,000 lei (about 420 dollars). The price of these Jews usually varied according to their "worth". This practice continued at a slower pace from 1965 under Nicolae Ceaușescu, a Romanian communist leader. During the 1950s, West Germany had been also paying Romania an amount of money in exchange for some Germans of Romania, and, just like the Jews (both of which were regarded as "co-nationals"), their price was "calculated". Ceaușescu, happy with these policies, even declared that "oil, Germans, and Jews are our most important export commodities".[67]

Israeli government paid to facilitate aliyah, and around 235,000 people emigrated from Romania to Israel under this agreement.[68] When Romania was under control of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, he received 10 million dollars per year, and only he had the access to the money transferred to the secret account. Israel also bought Romanian goods and invested into Romania's economy. After his death, Ceauşescu practically sold the Jews to Israel, and received between 4,000 and 6,000$ per person.[69] Israel could have transferred nearly 60 million dollars for the aliyah.[70] Another estimation is higher - according to Radu Ioanid, "Ceausescu sold 40,577 Jews to Israel for $112,498,800, at a price of $2,500 and later at $3,300 per head."[71]

From the Soviet Union and post-Soviet states

A mass emigration was politically undesirable for the Soviet regime. The only acceptable ground was family reunification, and a formal petition ("вызов", vyzov) from a relative from abroad was required for the processing to begin. Often, the result was a formal refusal. The risks to apply for an exit visa compounded because the entire family had to quit their jobs, which in turn would make them vulnerable to charges of social parasitism, a criminal offense. Because of these hardships, Israel set up the group Lishkat Hakesher in the early 1950s to maintain contact and promote aliyah with Jews behind the Iron Curtain.[citation needed]

From Israel's establishment in 1948 to the Six-Day War in 1967, Soviet aliyah remained minimal. Those who made aliyah during this period were mainly elderly people granted clearance to leave for family reunification purposes. Only about 22,000 Soviet Jews managed to reach Israel. In the wake of the Six-Day War, the USSR broke off the diplomatic relations with the Jewish state. An Anti-Zionist propaganda campaign in the state-controlled mass media and the rise of Zionology were accompanied by harsher discrimination of the Soviet Jews. By the end of the 1960s, Jewish cultural and religious life in the Soviet Union had become practically impossible, and the majority of Soviet Jews were assimilated and non-religious, but this new wave of state-sponsored anti-Semitism on one hand, and the sense of pride for victorious Jewish nation over Soviet-armed Arab armies on the other, stirred up Zionist feelings.[citation needed]

After the Dymshits-Kuznetsov hijacking affair and the crackdown that followed, strong international condemnations caused the Soviet authorities to increase the emigration quota. In the years 1960–1970, the USSR let only 4,000 people leave; in the following decade, the number rose to 250,000.[73] The exodus of Soviet Jews began in 1968.[74]

| Year | Exit visas to Israel |

Immigrants from the USSR[73] |

|---|---|---|

| 1968 | 231 | 231 |

| 1969 | 3,033 | 3,033 |

| 1970 | 999 | 999 |

| 1971 | 12,897 | 12,893 |

| 1972 | 31,903 | 31,652 |

| 1973 | 34,733 | 33,277 |

| 1974 | 20,767 | 16,888 |

| 1975 | 13,363 | 8,435 |

| 1976 | 14,254 | 7,250 |

| 1977 | 16,833 | 8,350 |

| 1978 | 28,956 | 12,090 |

| 1979 | 51,331 | 17,278 |

| 1980 | 21,648 | 7,570 |

| 1981 | 9,448 | 1,762 |

| 1982 | 2,692 | 731 |

| 1983 | 1,314 | 861 |

| 1984 | 896 | 340 |

| 1985 | 1,140 | 348 |

| 1986 | 904 | 201 |

Between 1968 and 1973, almost all Soviet Jews allowed to leave settled in Israel, and only a small minority moved to other Western countries. However, in the following years, the number of those moving to other Western nations increased.[74] Soviet Jews granted permission to leave were taken by train to Austria to be processed and then flown to Israel. There, the ones who chose not to go to Israel, called "dropouts", exchanged their immigrant invitations to Israel for refugee status in a Western country, especially the United States. Eventually, most Soviet Jews granted permission to leave became dropouts. Overall, between 1970 and 1988, some 291,000 Soviet Jews were granted exit visas, of whom 165,000 moved to Israel and 126,000 moved to the United States.[75] In 1989 a record 71,000 Soviet Jews were granted exodus from the USSR, of whom only 12,117 immigrated to Israel.

In 1989 the United States changed its immigration policy of unconditionally granting Soviet Jews refugee status. That same year, Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev ended restrictions on Jewish immigration, and the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991. Since then, about a million people from the former Soviet Union immigrated to Israel,[76] including approximately 240,000 who were not Jewish according to rabbinical law, but were eligible for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return.

The number of immigrants counted as halachically non-Jewish from the former USSR has been constantly rising ever since 1989. For example, in 1990 around 96% of the immigrants were halachically Jewish and only 4% were non-Jewish family members. However, in 2000, the proportion was: Jews (includes children from non-Jewish father and Jewish mother) - 47%, Non-Jewish spouses of Jews - 14%, children from Jewish father and non-Jewish mother - 17%, Non-Jewish spouses of children from Jewish father and non-Jewish mother - 6%, non-Jews with a Jewish grandparent - 14% & Non-Jewish spouses of non-Jews with a Jewish grandparent - 2%.[77]

Following the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War, Ukrainian Jews making aliyah from Ukraine reached 142% higher during the first four months of 2014 compared to the previous year.[78][79] In 2014, aliyah from the former Soviet Union went up 50% from the previous year with some 11,430 people or approximately 43% of all Jewish immigrants arrived from the former Soviet Union, propelled from the increase from Ukraine with some 5,840 new immigrants have come from Ukraine over the course of the year.[80][81]

The wave of aliyah from Russia since 2014 has been called "Putin's aliyah", "Putin's exodus", and "cheese aliyah" (foreign cheese was one of the first products to disappear from Russian shops because of anti-sanctions imposed by the Russian government).[82][83][84][85][86] The number of repatriants in this wave is comparable with that coming from the USSR between 1970 and 1988.[87]

Following 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Israel announced "Immigrants Come Home" operation. As of June 2022, more than 25,000 people arrived in Israel from Ukraine, Russia, Belarus and Moldova.[88]

From Latin America

In the 1999–2002 Argentine political and economic crisis that caused a run on the banks, wiped out billions of dollars in deposits and decimated Argentina's middle class, most of the country's estimated 200,000 Jews were directly affected. Some 4,400 chose to start over and move to Israel, where they saw opportunity.[citation needed]

More than 10,000 Argentine Jews have immigrated to Israel since 2000, joining the thousands of previous Argentine immigrants already there. The crisis in Argentina also affected its neighbour country Uruguay, from which about half of its 40,000-strong Jewish community left, mainly to Israel, in the same period. During 2002 and 2003 the Jewish Agency for Israel launched an intensive public campaign to promote aliyah from the region, and offered additional economic aid for immigrants from Argentina. Although the economy of Argentina improved, and some who had immigrated to Israel from Argentina moved back following South American country's economic growth from 2003 onwards, Argentine Jews continue to immigrate to Israel, albeit in smaller numbers than before. The Argentine community in Israel is about 50,000-70,000 people, the largest Latin American group in the country.[citation needed]

There has also been immigration from other Latin American countries that have experienced crises, though they have come in smaller numbers and are not eligible for the same economic benefits as immigrants to Israel from Argentina.[citation needed]

In Venezuela, growing antisemitism in the country, including antisemitic violence, caused an increasing number of Jews to move to Israel during the 2000s. For the first time in Venezuelan history, Jews began leaving for Israel in the hundreds. By November 2010, more than half of Venezuela's 20,000-strong Jewish community had left the country.[89][90]

From France

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish outreach |

|---|

| Core topics |

| Related topics |

From 2000 to 2009, more than 13,000 French Jews immigrated to Israel, largely as a result of growing anti-semitism in the country. A peak was reached in 2005, with 2,951 immigrants. However, between 20 and 30% eventually returned to France.[91]

In 2012, some 200,000 French citizens lived in Israel.[92] During the same year, following the election of François Hollande and the Jewish school shooting in Toulouse, as well as ongoing acts of anti-semitism and the European economic crisis, an increasing number of French Jews began buying property in Israel.[93] In August 2012, it was reported that anti-semitic attacks had risen by 40% in the five months following the Toulouse shooting, and that many French Jews were seriously considering immigrating to Israel.[94] In 2013, 3,120 French Jews immigrated to Israel, marking a 63% increase over the previous year.[95] In the first two months of 2014, French Jewish aliyah increased precipitously by 312% with 854 French Jews making aliyah over the first two months. Immigration from France throughout 2014 has been attributed to several factors, of which includes increasing antisemitism, in which many Jews have been harassed and attacked by a fusillade of local thugs and gangs, a stagnant European economy and concomitant high youth unemployment rates.[96][97][98][99]

During the first few months of 2014, The Jewish Agency of Israel continued to encourage an increase of French aliyah through aliyah fairs, Hebrew language courses, sessions which help potential immigrants to find jobs in Israel, and immigrant absorption in Israel.[100] A May 2014 survey revealed that 74 percent of French Jews considered leaving France for Israel; of those considering leaving, 29.9 percent cited anti-Semitism. Another 24.4 cited their desire to “preserve their Judaism,” while 12.4 percent said they were attracted by other countries. “Economic considerations” was cited by 7.5 percent of the respondents.[101] By June 2014, it was estimated by the end of 2014 a full 1 percent of the French Jewish community will have made aliyah to Israel, the largest in a single year. Many Jewish leaders stated the emigration is being driven by a combination of factors, including the cultural gravitation towards Israel and France's economic woes, especially for the younger generation drawn by the possibility of other socioeconomic opportunities in the more vibrant Israeli economy.[102][103] During the Hebrew year 5774 (September 2013 - September 2014) for the first time ever, more Jews made aliyah from France than any other country, numbering approximately 6,000 and fleeing antisemitism, pro-Palestinian and anti-Zionist violence, as well as and economic malaise.[104][105]

In January 2015, events such as the Charlie Hebdo shooting and Porte de Vincennes hostage crisis created a shock wave of fear across the French Jewish community. As a result of these events, the Jewish Agency planned an aliyah plan for 120,000 French Jews who wished to make aliyah.[106][107] In addition, with Europe's stagnant economy, many affluent French Jewish skilled professionals, businesspeople and investors sought Israel as a start-up haven for international investments, as well as for job and new business opportunities.[108] In addition, Dov Maimon, a French Jewish émigré who studies migration as a senior fellow at the Jewish People Policy Institute, expects as many as 250,000 French Jews to make aliyah by 2030.[108]

Hours after an attack and an ISIS flag was raised on a gas factory near Lyon where the severed head of a local businessman was pinned to the gates on June 26, 2015, Immigration and Absorption Minister Ze’ev Elkin strongly urged the French Jewish community to move to Israel and made it a national priority for Israel to welcome French Jews with open arms.[109][110] Immigration from France increased: in the first half of 2015, approximately 5,100 French Jews made aliyah to Israel, or 25% more than in the same period during the previous year.[111][112]

Following the November 2015 Paris attacks committed by suspected ISIS affiliates in retaliation for Opération Chammal, one source reported that 80 percent of French Jews were considering making aliyah.[113][114][115] According to the Jewish Agency, nearly 6,500 French Jews made aliyah between January and November 2015.[116][117][118]

From North America

More than 200,000 North American immigrants live in Israel. There has been a steady flow of immigration from North America since Israel's inception in 1948.[119][120]

Several thousand American Jews moved to Mandate Palestine before the State of Israel was established. From Israel's establishment in 1948 to the Six-Day War in 1967, aliyah from the United States and Canada was minimal. In 1959, a former President of the Association of Americans and Canadians in Israel estimated that out of the 35,000 American and Canadian Jews who had made aliyah, only 6,000 remained.[121]

Following the Six-Day War in 1967, and the subsequent euphoria among world Jewry, significant numbers arrived in the late 1960s and 1970s, whereas it had been a mere trickle before. Between 1967 and 1973, 60,000 North American Jews immigrated to Israel. However, many of them later returned to their original countries. An estimated 58% of American Jews who immigrated to Israel between 1961 and 1972 ended up returning to the United States.[122][123]

Like Western European immigrants, North Americans tend to immigrate to Israel more for religious, ideological, and political purposes, and not financial or security ones.[124] Many immigrants began arriving in Israel after the First and Second Intifada, with a total of 3,052 arriving in 2005 — the highest number since 1983.[125]

Nefesh B'Nefesh, founded in 2002 by Rabbi Yehoshua Fass and Tony Gelbart, works to encourage aliyah from North America and the UK by providing financial assistance, employment services and streamlined governmental procedures. Nefesh B’Nefesh works in cooperation with the Jewish Agency and the Israeli Government in increasing the numbers of North American and British immigrants.[citation needed]

Following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, American Jewish immigration to Israel rose. This wave of immigration was triggered by Israel's lower unemployment rate, combined with financial incentives offered to new Jewish immigrants. In 2009, aliyah was at its highest in 36 years, with 3,324 North American Jews making aliyah.[126]

Since the 1990s

Since the mid-1990s, there has been a steady stream of South African, American and French Jews who have either made aliyah, or purchased property in Israel for potential future immigration. Over 2,000 French Jews moved to Israel each year between 2000 and 2004 due to anti-Semitism in France.[127] The Bnei Menashe Jews from India, whose recent discovery and recognition by mainstream Judaism as descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes is subject to some controversy, slowly started their aliyah in the early 1990s and continue arriving in slow numbers.[128] Organizations such as Nefesh B'Nefesh and Shavei Israel help with aliyah by supporting financial aid and guidance on a variety of topics such as finding work, learning Hebrew, and assimilation into Israeli culture.

In early 2007 Haaretz reported that aliyah for the year of 2006 was down approximately 9% from 2005, "the lowest number of immigrants recorded since 1988".[129] The number of new immigrants in 2007 was 18,127, the lowest since 1988. Only 36% of these new immigrants came from the former Soviet Union (close to 90% in the 1990s) while the number of immigrants from countries like France and the United States was stable.[130] Some 15,452 immigrants arrived in Israel in 2008 and 16,465 in 2009.[131] On October 20, 2009, the first group of Kaifeng Jews arrived in Israel, in an aliyah operation coordinated by Shavei Israel.[132][133][134] Shalom Life reported that over 19,000 new immigrants arrived in Israel in 2010, an increase of 16 percent over 2009.[135]

Paternity testing

In 2013, the office of the Prime Minister of Israel announced that some people born out of wedlock, "wishing to immigrate to Israel could be subjected to DNA testing" to prove their paternity is as they claim. A Foreign Ministry spokesman said the genetic paternity testing idea is based on the recommendations of Nativ, an Israeli government organization that has helped Soviet and post-Soviet Jews with aliyah since the 1950s.[136]

Holiday

Yom HaAliyah (Aliyah Day) (Hebrew: יום העלייה) is an Israeli national holiday celebrated annually according to the Jewish calendar on the tenth of the Hebrew month of Nisan to commemorate the Jewish people entering the Land of Israel as written in the Hebrew Bible, which happened on the tenth of the Hebrew month of Nisan (Hebrew: י' ניסן).[137] The holiday was also established to acknowledge Aliyah, immigration to the Jewish state, as a core value of the State of Israel, and honor the ongoing contributions of Olim, Jewish immigrants, to Israeli society. Yom HaAliyah is also observed in Israeli schools on the seventh of the Hebrew month of Cheshvan.[138]

The opening clause of the Yom HaAliyah Law states:

מטרתו של חוק זה לקבוע יום ציון שנתי להכרה בחשיבותה של העלייה לארץ ישראל כבסיס לקיומה של מדינת ישראל, להתפתחותה ולעיצובה כחברה רב־תרבותית, ולציון מועד הכניסה לארץ ישראל שאירע ביום י׳ בניסן.[139]

The purpose of this law is to set an annual holiday to recognize the importance of Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel as the basis for the existence of the State of Israel, its development and design as a multicultural society, and to mark the date of entry into the Land of Israel that happened on the tenth of Nisan.

— Yom HaAliyah Law

The original day chosen for Yom HaAliyah, the tenth of Nisan, is laden with symbolism. Although a modern holiday created by the Knesset of Israel, the tenth of Nisan is a date of religious significance for the Jewish People as recounted in the Hebrew Bible and in traditional Jewish thought.[140]

On the tenth of Nisan, according to the biblical narrative in the Book of Joshua, Joshua and the Israelites crossed the Jordan River at Gilgal into the Promised Land while carrying the Ark of the Covenant. It was thus the first documented "mass aliyah." On that day, God commanded the Israelites to commemorate and celebrate the occasion by erecting twelve stones with the text of the Torah engraved upon them. The stones represented the entirety of the Jewish nation's twelve tribes and their gratitude for God's gift of the Land of Israel (Hebrew: אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל, Modern: Eretz Yisrael, Tiberian: ʼÉreṣ Yiśrāʼēl) to them.[141]

Yom HaAliyah, as a modern holiday celebration, began in 2009 as a grassroots community initiative and young Olim self-initiated movement in Tel Aviv, spearheaded by the TLV Internationals organization of the Am Yisrael Foundation.[142] On June 21, 2016, the Twentieth Knesset voted in favor of codifying the grassroots initiative into law by officially adding Yom HaAliyah to the Israeli national calendar.[143] The Yom HaAliyah bill[144] was co-sponsored by Knesset members from different parties in a rare instance of cooperation across the political spectrum of the opposition and coalition.[145]

Statistics

Recent trends

| Country | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10,673 | 16,060 | 6,507 | 7,500 | 43,685 | ||

| 6,561 | 6,329 | 2,917 | 2,123 | 15,213 | ||

| 3,052 | 3,141 | 2,661 | 4,000 | 3,261 | ||

| 2,723 | 2,470 | 2,351 | 2,819 | 2,049[b] | ||

| 1,467 | 665 | 712 | 1,589 | 1,498[c] | ||

| 969 | 945 | 586 | 780 | 1,993[d] | ||

| 693 | 673 | 438 | 356[e] | |||

| 523 | 490 | 526[f] | ||||

| 347 | ||||||

| 286 | 340 | 633 | 985[g] | |||

| 332 | 442 | 280 | 373 | 426[h] | ||

| 401 | 203 | 318 | ||||

| 185 | ||||||

| 152 | 174 | |||||

| 121 | ||||||

| 110 | ||||||

| 91 | ||||||

| 86 | ||||||

| 43 | ||||||

| Total | 29,509 | 30,403 | 35,651 | 21,120 | 28,601 | 74,915 |

Historic data

The number of immigrants since 1882 by period, continent of birth, and country of birth is given in the table below. Continent of birth and country of birth data is almost always unavailable or nonexistent for before 1919.[159][160][148]

| Region/Country | 1882– 1918 |

1919– 1948 |

1948– 1951 |

1952– 1960 |

1961– 1971 |

1972– 1979 |

1980– 1989 |

1990– 2001 |

2002– 2010 |

2011– 2020 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4,033 | 93,282 | 143,485 | 164,885 | 19,273 | 28,664 | 55,619 | 31,558 | 20,843 | 561,642 | ||

| 0 | 10 | 59 | 98 | 309 | 16,971 | 45,131 | 23,613 | 10,500 | 96,691 | ||

| 994 | 3,810 | 3,433 | 12,857 | 2,137 | 1,830 | 1,682 | 1,967 | 324 | 29,034 | ||

| 0 | 16,028 | 17,521 | 2,963 | 535 | 372 | 202 | 166 | 21 | 37,808 | ||

| 873 | 30,972 | 2,079 | 2,466 | 219 | 67 | 94 | 36 | 5 | 36,811 | ||

| 0 | 28,263 | 95,945 | 130,507 | 7,780 | 3,809 | 3,276 | 2,113 | 384 | 272,077 | ||

| 259 | 666 | 774 | 3,783 | 5,604 | 3,575 | 3,283 | 1,693 | 2,560 | 22,197 | ||

| 0 | 13,293 | 23,569 | 11,566 | 2,148 | 1,942 | 1,607 | 1,871 | 398 | 56,394 | ||

| 0 | 37 | 22 | 145 | 393 | 82 | 26 | 14 | 719 | |||

| Other (Africa) | 1,907 | 203 | 83 | 500 | 148 | 16 | 318 | 85 | 24 | 3,284 | |

| 7,579 | 3,822 | 6,922 | 42,400 | 45,040 | 39,369 | 39,662 | 36,209 | 51,370 | 272,373 | ||

| 238 | 904 | 2,888 | 11,701 | 13,158 | 10,582 | 11,248 | 9,450 | 3,150 | 63,319 | ||

| 0 | 116 | 107 | 742 | 1,146 | 835 | 977 | 524 | 4,447 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 199 | 94 | 80 | 53 | 84 | 510 | |||

| 0 | 304 | 763 | 2,601 | 1,763 | 1,763 | 2,356 | 2,037 | 4,320 | 15,907 | ||

| 316 | 236 | 276 | 2,169 | 2,178 | 1,867 | 1,963 | 1,700 | 6,340 | 17,045 | ||

| 0 | 48 | 401 | 1,790 | 1,180 | 1,040 | 683 | 589 | 5,731 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 415 | 552 | 475 | 657 | 965 | 3,064 | |||

| 0 | 14 | 88 | 405 | 79 | 42 | 629 | 606 | 1,863 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 38 | 44 | 67 | 69 | 258 | |||

| 0 | 48 | 168 | 736 | 861 | 993 | 1,049 | 697 | 4,552 | |||

| 70 | 0 | 13 | 91 | 129 | 124 | 142 | 42 | 611 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 43 | 48 | 50 | 40 | 245 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 269 | 243 | 358 | 612 | 1,539 | 3,021 | |||

| 2,000[161] | 6,635 | 1,711 | 1,553 | 18,671 | 20,963 | 18,904 | 17,512 | 15,445 | 32,000 | 135,394 | |

| 0 | 66 | 425 | 1,844 | 2,199 | 2,014 | 983 | 1,555 | 9,086 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 297 | 245 | 180 | 418 | 602 | 1,742 | |||

| Other (Central America) | 0 | 17 | 43 | 129 | 104 | 8 | 153 | 157 | 611 | ||

| Other (South America) | 0 | 42 | 194 | 89 | 62 | 0 | 66 | 96 | 549 | ||

| Other (Americas/Oceania) | 318 | 313 | 0 | 148 | 3 | 8 | 44 | 12 | 846 | ||

| 40,776 | 237,704 | 37,119 | 56,208 | 19,456 | 14,433 | 75,687 | 17,300 | 1,370 | 500,053 | ||

| 0 | 2,303 | 1,106 | 516 | 132 | 57 | 21 | 13 | 4,148 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 147 | 83 | 383 | 138 | 33 | 784 | |||

| 0 | 504 | 217 | 96 | 43 | 78 | 277 | 74 | 190 | 1,479 | ||

| 0 | 21 | 35 | 28 | 21 | 12 | 32 | 0 | 149 | |||

| 0 | 2,176 | 5,380 | 13,110 | 3,497 | 1,539 | 2,055 | 961 | 1,180 | 29,898 | ||

| 0 | 101 | 46 | 54 | 40 | 60 | 205 | 42 | 548 | |||

| 3,536 | 21,910 | 15,699 | 19,502 | 9,550 | 8,487 | 4,326 | 1,097 | 84,107 | |||

| 0 | 123,371 | 2,989 | 2,129 | 939 | 111 | 1,325 | 130 | 130,994 | |||

| 0 | 411 | 868 | 1,021 | 507 | 288 | 1,148 | 1,448 | 5,691 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 9 | 25 | 34 | 57 | 98 | 32 | 255 | |||

| 0 | 6 | 9 | 23 | 6 | 9 | 15 | 0 | 68 | |||

| 0 | 235 | 846 | 2,208 | 564 | 179 | 96 | 34 | 4,162 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 100 | 36 | 155 | |||

| 0 | 177 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 186 | |||

| 0 | 2,678 | 1,870 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,664 | 23 | 6,235 | |||

| 8,277 | 34,547 | 6,871 | 14,073 | 3,118 | 2,088 | 1,311 | 817 | 71,102 | |||

| 61,988[j] | 12,422[k] | 74,410 | |||||||||

| 2,600[162] | 15,838 | 48,315 | 1,170 | 1,066 | 51 | 17 | 683 | 103 | 69,843 | ||

| Other (Asia) | 13,125 | 947 | 0 | 60 | 21 | 45 | 205 | 30 | 14,433 | ||

| 377,487 | 332,802 | 106,305 | 162,070 | 183,419 | 70,898 | 888,603 | 96,165 | 162,320 | 2,380,069 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 376 | 0 | 389 | |||

| 7,748 | 2,632 | 610 | 1,021 | 595 | 356 | 368 | 150 | 13,480 | |||

| 0 | 291 | 394 | 1,112 | 847 | 788 | 1,053 | 873 | 5,358 | |||

| 7,057 | 37,260 | 1,680 | 794 | 118 | 180 | 3,999 | 341 | 51,429 | |||

| 16,794 | 18,788 | 783 | 2,754 | 888 | 462 | 527 | 217 | 41,213 | |||

| 0 | 27 | 46 | 298 | 292 | 411 | 389 | 85 | 1,548 | |||

| 0 | 9 | 20 | 172 | 184 | 222 | 212 | 33 | 852 | |||

| 1,637 | 3,050 | 1,662 | 8,050 | 5,399 | 7,538 | 11,986 | 13,062 | 38,000 | 90,384 | ||

| 52,951 | 8,210 | 1,386 | 3,175 | 2,080 | 1,759 | 2,442 | 866 | 72,869 | |||

| 8,767 | 2,131 | 676 | 514 | 326 | 147 | 127 | 48 | 12,736 | |||

| 10,342 | 14,324 | 9,819 | 2,601 | 1,100 | 1,005 | 2,444 | 730 | 42,365 | |||

| 0 | 14 | 46 | 145 | 157 | 233 | 136 | 54 | 785 | |||

| 1,554 | 1,305 | 414 | 940 | 713 | 510 | 656 | 389 | 6,481 | |||

| 0 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 83 | |||

| 1,208 | 1,077 | 646 | 1,470 | 1,170 | 1,239 | 997 | 365 | 8,172 | |||

| 0 | 17 | 14 | 36 | 55 | 126 | 120 | 19 | 387 | |||

| 170,127 | 106,414 | 39,618 | 14,706 | 6,218 | 2,807 | 3,064 | 764 | 343,718 | |||

| 0 | 16 | 22 | 66 | 56 | 55 | 47 | 28 | 290 | |||

| 41,105 | 117,950 | 32,462 | 86,184 | 18,418 | 14,607 | 6,254 | 711 | 317,691 | |||

| 47,500[163][m] | 52,350 | 8,163 | 13,743 | 29,376 | 137,134 | 29,754 | 844,139[n] | 72,520[o] | 118,000[p] | 1,352,679 | |

| 0 | 80 | 169 | 406 | 327 | 321 | 269 | 178 | 1,750 | |||

| 0 | 32 | 51 | 378 | 372 | 419 | 424 | 160 | 1,836 | |||

| 0 | 131 | 253 | 886 | 634 | 706 | 981 | 585 | 4,176 | |||

| 1,574 | 1,907 | 1,448 | 6,461 | 6,171 | 7,098 | 5,365 | 3,725 | 6,320 | 40,069 | ||

| 1,944 | 7,661 | 320 | 322 | 126 | 140 | 2,029 | 162 | 12,704 | |||

| Other (Europe) | 2,329 | 1,281 | 3 | 173 | 32 | 0 | 198 | 93 | 4,109 | ||

| Not known | 52,982 | 20,014 | 3,307 | 2,265 | 392 | 469 | 422 | 0 | 0 | 79,851 | |

| Total | 62,500[164][q] | 482,857 | 687,624 | 297,138 | 427,828 | 267,580 | 153,833 | 1,059,993 | 181,233 | 236,903 | 3,857,489 |

See also

- Demographics of Israel

- Galut

- Historical Jewish population comparisons

- History of the Jews in the Land of Israel

- Homeland for the Jewish people

- Illegal immigration from Africa to Israel

- Israeli identity card

- Israeli passport

- Jewish population by country

- Kibbutz volunteer

- Law of Return

- Olim L'Berlin

- Visa policy of Israel

- Yerida

- Yom HaAliyah

References

Notes

- ^ Between 1880 and 1907, the number of Jews in Palestine grew from 23,000 to 80,000. Most of the community resided in Jerusalem, which already had a Jewish majority at the beginning of the influx. (Footnote: Mordecai Elia, Ahavar Tziyon ve-Kolel Hod (Tel Aviv, 1971), appendix A. Between 1840 and 1880 the Jewish settlement in Palestine grew in numbers from 9,000 to 23,000.) The First Aliyah accounted for only a few thousand of the new-comers, and the number of the Biluim among them was no more than a few dozen. Jewish immigration to Palestine had begun to swell in the 1840s, following the liberalization of Ottoman domestic policy (the Tanzimat Reforms) and as a result of the protection extended to immigrants by the European consulates set up at the time in Jerusalem and Jaffa. The majority of immigrants came from Eastern and Central Europe – the Russian Empire, Romania, and Hungary – and were not inspired by modern Zionist ideology. Many were motivated by a blend of traditional ideology (e.g., belief in the sanctity of the land of Israel and in the redemption of the Jewish people through the return to Zion) and practical considerations (e.g., desire to escape the worsening conditions in their lands of origin and to improve their lot in Palestine). The proto-Zionist ideas which had already crystallized in Western Europe during the late 1850s and early 1860s were gaining currency in Eastern Europe.[36]

- ^ Between January 1 and December 1, 2022[156]

- ^ Part of Operation Tzur Israel[156]

- ^ Between January 1 and December 1, 2022[156]

- ^ Between January 1 and December 1, 2022[156]

- ^ Between January 1 and December 1, 2022[156]

- ^ Between January 1 and December 1, 2022[156]

- ^ Between January 1 and December 1, 2022[156]

- ^ Before 1995, the aliyah from the Asian republics of the former Soviet Union were counted in the total of the aliyah from the (former) Russian Empire/Soviet Union.

- ^ Specifically, 15973 from Uzbekistan and 7609 from Georgia during 1990–1999.

- ^ Specifically, 8817 from Uzbekistan and 3766 from Georgia during 2000–2010.

- ^ Includes Asian parts of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union until 1991 and Asian parts of modern Russia. Also includes Jews from the former Soviet Union whose republic of origin is unknown.

- ^ This number is an average of two different estimates from page 93 of this book.

- ^ Specifically, 114406 from Ukraine and 91756 from Russia during 1990–1999.

- ^ Specifically, 50441 from Russia and 50061 from Ukraine during 2000–2010.

- ^ Specifically, 45670 from Ukraine and 5530 from Belarus.

- ^ This number is an average of two different estimates.

Citations

- ^ "'Aliyah': The Word and Its Meaning". 2005-05-15. Archived from the original on 2009-12-19. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ a b On, Raphael R. Bar (1969). "Israel's Next Census of Population as a Source of Data on Jews". Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies / דברי הקונגרס העולמי למדעי היהדות. ה: 31–41. JSTOR 23524099. p. 31: The estimated 24,000 Jews in Palestine in 1882 represented just 0.3% of the world's Jewish population [paraphrase].

- ^ a b Mendel, Yonatan (5 October 2014). The Creation of Israeli Arabic: Security and Politics in Arabic Studies in Israel. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-137-33737-5. Note 28: The exact percentage of Jews in Palestine prior to the rise of Zionism is unknown. However, it probably ranged from 2 to 5 per cent. According to Ottoman records, a total population of 462,465 resided in 1878 in what is today Israel/Palestine. Of this number, 403,795 (87 per cent) were Muslim, 43,659 (10 per cent) were Christian and 15,011 (3 per cent) were Jewish (quoted in Alan Dowty, Israel/Palestine, Cambridge: Polity, 2008, p. 13). See also Mark Tessler, A History of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1994), pp. 43 and 124.

- ^ Rosenzweig, Rafael N. (1989). The Economic Consequences of Zionism. E. J. Brill. p. 1. ISBN 978-90-04-09147-4.

Zionism, the urge of the Jewish people to return to Palestine, is almost as ancient as the Jewish diaspora itself. Some Talmudic statements ... Almost a millennium later, the poet and philosopher Yehuda Halevi ... In the 19th century ...

- ^ Schneider, Jan (June 2008). "Israel". Focus Migration. 13. Hamburg Institute of International Economics. ISSN 1864-6220. Archived from the original on 2019-05-14. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ a b Branovsky, Yael (6 May 2008). "400 olim arrive in Israel ahead of Independence Day". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ DellaPergola, Sergio (2014). Dashefsky, Arnold; Sheskin, Ira (eds.). "World Jewish Population, 2014". Current Jewish Population Reports. 11. The American Jewish Year Book (Dordrecht: Springer): 5–9, 16–17. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

Israel's Jewish population (not including about 348,000 persons not recorded as Jews in the Population Register and belonging to families initially admitted to the country within the framework of the Law of Return) surpassed six million in 2014 (42.9% of world Jewry).

- ^ "Move On Up". The Forward. Archived from the original on 2011-10-18. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ Alroey 2015, p. 110: "The sweeping and uncritical use of the two terms, 'aliyah' and 'immigration' is one of the major factors in the emergence of the divergent treatment of similar data. In the Zionist ethos, aliyah has nothing in common with the migration of other peoples. Zionist historiography takes it as axiomatic that the Jews who came to the country as part of the pioneering early waves were 'olim' and not simply 'immigrants'. The latent ideological charge of the term 'aliyah' is so deeply rooted in the Hebrew language that it is almost impossible to distinguish between Jews who 'merely' immigrated to Palestine and those who made aliyah to the Land of Israel. Jewish social scientists of the early twentieth century were the first to distinguish aliyah from general Jewish migration. The use of 'aliyah' as a typological phenomenon came into vogue with the publication of Arthur Ruppin's Soziologie der Juden in 1930 (English: The Jews in the Modern World, 1934) ... in the eighth chapter, which looks at migration, Ruppin seems to have found it difficult to free himself of the Zionist terminology that was dominant in that period. [Ruppin wrote that whereas] Jewish immigration to the United States was propelled by economic hardship and pogroms, the olim (not immigrants) came to Palestine with the support of the Hoveve Tsiyon, with whom they felt a high degree of ideological conformity."

- ^ Alroey 2015, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Golinkin, David. "Is It A Mitzvah To Make Aliyah?". Responsa in a Moment. Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Leff, Barry. "The Mitzvah of Aliyah". Kef International. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ עליית החסידים ההמונית לא"י [The mass exodus of the faithful to Israel]. ץראב םתושרתשהו א"רגה ידימלת. Daat. 2008-08-02. Archived from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ Munayyer, Youssef (23 May 2012). "Not All Citizens Are Equal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Shoham 2013.

- ^ Horovitz, Greenberg, and Zilberg, Al Naharot Bavel (Bible Lands Museum press, 2015), inscription 15

- ^ Hahistoriya shel Eretz Israel – Shilton Romi, Yisrael Levine, p. 47, ed. Menahem Stern, 1984, Yad Izhak Ben Zvi – Keter

- ^ Schwartz, Joshua (1983). "Aliya from Babylonia During the Amoraic Period (200–500 AD)". In Levine, Lee (ed.). The Jerusalem Cathedra: Studies in the History, Archaeology, Geography and Ethnography of the Land of Israel. Yad Izhak Ben Zvi and Wayne State University Press. pp. 58–69.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1983). "Aliya and Pilgrimage in the Early Arab Period (634–1009)". The Jerusalem Cathedra: Studies in the History, Archaeology, Geography and Ethnography of the Land of Israel. Yad Izhak Ben Zvi and Wayne State University Press.

- ^ "יהדות הגולה והכמיהה לציון, 1840–1240". Tchelet (in Hebrew). 2008-08-02. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ^ Krauss, Samuel (1926). "L'émigration de 300 Rabbins en Palestine en l'an 1211". Revue des études juives. 82 (163): 333–352. doi:10.3406/rjuiv.1926.5521.

- ^ Kanarfogel, Ephraim (1986). "The 'Aliyah of "Three Hundred Rabbis" in 1211: Tosafist Attitudes toward Settling in the Land of Israel". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 76 (3): 191–215. doi:10.2307/1454507. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1454507.

- ^ Lehmann, Matthias B. (2008). "Rethinking Sephardi Identity: Jews and Other Jews in Ottoman Palestine". Jewish Social Studies. 15 (1): 81–109. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 40207035.

- ^ Ray, Jonathan (2009). "Iberian Jewry between West and East: Jewish Settlement in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean". Mediterranean Studies. 18: 44–65. doi:10.2307/41163962. ISSN 1074-164X. JSTOR 41163962.

- ^ a b c Zemer, Moshe (1997-11-30), Jacob, Walter; Zemer, Moshe (eds.), "ALIYAH: CONFLICT AND AMBIVALENCE As Reflected in Medieval Responsa", Israel and the Diaspora in Jewish Law: Essays and Responsa, Berghahn Books, pp. 115–148, doi:10.1515/9781800738843-007, ISBN 978-1-80073-884-3, retrieved 2025-01-09

- ^ The Journal of Jewish Studies. Jewish Chronicle Publications. 1999. p. 317.

- ^ Yisraeli, Oded (November 2017). "Jerusalem in Naḥmanides's Religious Thought: The Evolution of the "Prayer over the Ruins of Jerusalem"". AJS Review. 41 (2): 409–453. doi:10.1017/S0364009417000435. ISSN 0364-0094.

- ^ a b Morgenstern, Arie (2010-08-11). "THE HURVA SYNAGOGUE 1700-2010". Jewish Action. Retrieved 2025-01-09.

- ^ David, Abraham (2010-05-24). To Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in 16th-Century Eretz-Israel. University of Alabama Press. pp. 15–23. ISBN 978-0-8173-5643-9.

- ^ Birnbaum, Marianna D. (2003-01-01). The Long Journey of Gracia Mendes. Central European University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-963-9241-67-1.

- ^ Goldish, Matt (2017), Sutcliffe, Adam; Karp, Jonathan (eds.), "Sabbatai Zevi and the Sabbatean Movement", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 7: The Early Modern World, 1500–1815, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 7, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 491–521, ISBN 978-0-521-88904-9, retrieved 2025-01-09

- ^ a b Katz-Oz, Avraham (2017). "Agricultural Settlement: Up to the Present and into the Future". Jewish Political Studies Review. 28 (3/4): 60–65. ISSN 0792-335X. JSTOR 26416731.

- ^ Etkes, Immanuel (2013). "On the Motivation for Hasidic Immigration (Aliyah) to the Land of Israel". Jewish History. 27 (2/4): 337–351. doi:10.1007/s10835-013-9194-6. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709800.

- ^ Ilani, Ofri (2008-01-06). "The Messiah brought the first immigrants". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ Morgenstern, Arie; Linsider, Joel A. (2006-07-01). Hastening Redemption: Messianism and the Resettlement of the Land of Israel. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0195305787.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-530578-4.

- ^ Salmon 1978.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (1965). Davison, Roderick H. (ed.). "The Ottoman Empire in the Mid-Nineteenth Century: A Review". Middle Eastern Studies. 1 (3): 283–295. doi:10.1080/00263206508700018. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4282119.

- ^ Shoham 2013, p. 35-37: "The term Aliya as defining historical periods appeared only when talking about Jewish history on the long-durée, when looking back to thousands of years. In 1914, the Zionist activist Shemaryahu Levin [wrote]: “Now at the time of the Third Aliya we can witness the fulfillment of the vision of the Second Aliya, in the days of Nehemiah.” Levin based this remark on a contemporaneous historiographical convention, according to which Jewish history knew two main aliyot to the Land of Israel in biblical times: “the First Aliya” took place in the time of biblical Zerubavel, after Cyrus’ declaration, while “the Second Aliya” took place in the days of Ezra and Nehemiah, about 80 years later… Levin’s periodization was not circulated in public, including among practical Zionists. It achieved dominance only after the WW I, in a way different from both Levin’s intention and counting...Along with analogies of the Balfour Declaration to Cyrus, 2,500 years earlier, many leaders began to write and talk about the forthcoming immigration as “the Third Aliya”, which would continue the previous two, those that departed from Babylonia to establish the second temple. About two months after the Balfour Declaration, Isaac Nissenbaum from the Mizrachi (Zionist-religious) movement published an optimis- tic article in which he anticipated a Hebrew majority in Palestine soon."

- ^ Shoham 2013, p. 42: "The first text in which the periodization as we know it today may be found was an article surveying historical immigrations to and from Palestine, written by the widely recognized writer Y.H. Brenner, and published in October 1919…"