American Epic (film series)

| American Epic | |

|---|---|

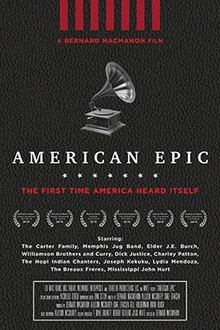

Theatrical release poster | |

| Written by |

|

| Directed by | Bernard MacMahon |

| Music by |

|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| Production | |

| Producers |

|

| Cinematography | Vern Moen |

| Editors |

|

| Running time | 310 minutes (theatrical version) |

| Production companies | Lo-Max Films, Wildwood Enterprises |

| Original release | |

| Network | BBC PBS |

| Release | May 16 – June 6, 2017 |

American Epic is a documentary film series about the first recordings of roots music in the United States during the 1920s and their cultural, social and technological impact on North America and the world.[1] Directed and co-written by Bernard MacMahon, the story is told through twelve ethnically and musically diverse musicians who auditioned for and participated in these pioneering recording sessions: The Carter Family, the Memphis Jug Band, Elder J.E. Burch, The Williamson Brothers, Dick Justice, Charley Patton, The Hopi Indian Chanters, Joseph Kekuku, Lydia Mendoza, the Breaux Family, Mississippi John Hurt and Blind Willie Johnson.[2] The film series is the core of the American Epic media franchise, which includes several related works.

The film series was created, written and produced by MacMahon, Allison McGourty and Duke Erikson. It was first broadcast on May 16, 2017, in the United States and was narrated by Robert Redford.[2] The film was the result of ten years of intensive field research and postulated a radically new take on American history, namely that America was democratized through the invention of electrical sound recording and the subsequent auditions the record labels held across North America in the late 1920s, which were open to every ethnic minority and genre of music.[3][4] The films contained many previously untold stories,[5][6] a vast amount of previously unseen and extremely rare archival footage[7][8] and dramatically advanced audio restorations of the 1920s and 1930s recordings.[9][10]

MacMahon decided all the interviewees had to personally have known the long-deceased subjects of the films, and these interviews were conducted on the location where the musicians had lived, accompanied by panoramic tracking shots of the geographical locations both present and vintage to give a sense of the wildly varied North American landscape and its influence on the music.[7][11] During pre-production, when MacMahon presented his vision for the films and the archival footage to Robert Redford at their first meeting, Redford pronounced it "America's greatest untold story."[12]

The film series received a number of awards, including the Foxtel Audience Award at the 2016 Sydney Film Festival[13] and the Discovery Award at the 2016 Calgary International Film Festival.[14] It was nominated for a Primetime Emmy.[15] On April 23, 2018, the Focal International Awards nominated American Epic for Best Use of Footage in a History Feature and Best Use of Footage in a Music Production.[16] Many critics have cited the American Epic films as being one of the best music documentaries ever made.[17][18][19][20][21]

Episodes

[edit]This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (March 2023) |

In the Roaring Twenties two worlds collided: one Southern, rural and traditional; the other Northern, urban, and industrial. America was in motion. Record companies sent scouts across the United States, searching for new artists and sounds. They traveled to remote regions, auditioned thousands of everyday Americans, and issued their music on phonograph records. It was the first time America heard itself. The artists they discovered shaped our world. Here, are some of their stories ...

— Robert Redford, from episode one

| No. | Title [22] | Original air date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "The Big Bang" | May 16, 2017[22] | |

|

Overview

The Carter Family | |||

| 2 | "Blood and Soil" | May 23, 2017[22] | |

|

Overview

Charley Patton | |||

| 3 | "Out of the Many, the One" | May 30, 2017[22] | |

|

Overview  Lydia Mendoza  Blind Willie Johnson | |||

Development

[edit]Inspiration

[edit]The grand purpose of the film is a love of America. As a small boy, I loved American films and movies. I grew up in suburban South London, and I remember looking up at the sky at the planes flying over from Heathrow and wondering if they were going to America and wanting to be on one of those planes.[23]

Director Bernard MacMahon said, "America has fascinated me since I was a child. My big love is American cinema, especially early American cinema, and I've always been fascinated by that period in the 20s when the technology and artistic language of the film were being invented."[24] He commented that at the same time he became fascinated with the 20s music recording artists.[24] He revealed the American Epic films were inspired by an advert in a magazine in 2006 for a blues festival in the Lake District, featuring Honeyboy Edwards, Homesick James, and Robert Lockwood Jr. - three men in their nineties who had grown up in the 20s at the height of the Delta blues era.[25][26] According to MacMahon, "A voice inside me said, 'I need to take a camera crew and film there. Someday I'm going to need this.'"[27]

"So we arranged to bring a [film] crew to the country inn where they were staying and filmed them talking about their youth and the music they had grown up with, including their memories of the formative genius of the Delta style, Charley Patton."[25] MacMahon recalled, "It was an amazing experience listening to these men who had lived through all the changes from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century…watching them sitting together, trading stories and talking about the music and the Delta and how both had changed, and getting a sense of their outlook and the way they related to each other was a very profound experience."[25] MacMahon said that when he screened the footage for his producer and screenwriting partner, Allison McGourty, she said, "This is great…We need to make this into something larger."[21] MacMahon decided the films would "explore the vast range of ethnic, rural, and regional music recorded in the United States during the late 1920s."[28] A story he considered would bring together music, social issues, freedom of speech and technology.[29] He also viewed the story as fundamental in culturally, creatively and technologically shaping and influencing the modern world.[4][5] MacMahon said this was the first time America heard itself. He posited that these 1920s recordings "allowed working people, from Native American farmers to a woman picking cotton in Mississippi, to have their thoughts and feelings distributed on records throughout the whole country. On the modern digital platform, we take that freedom of speech for granted. Back then, it was a revolutionary idea."[5]

Research

[edit]MacMahon began extensively researching the period, concentrating on approximately 100 performers who had made recordings in the late 20s and early 30s at the field recording sessions.[30][26] With very little information about the 1920s field recording sessions and the artists involved published in books,[31] MacMahon elected to research almost exclusively in the field by tracking down eyewitnesses and direct family members to piece together the most accurate picture of the events at that time.[5] One of the artists he was endeavoring to track down was Dick Justice. Suspecting that Justice was from West Virginia and a coal miner, MacMahon began running stories in the local newspapers from the 1920s coal mining communities in West Virginia that were still in print. After a number of failed attempts, he ran an advert in the Logan Banner that read, "British film company looking for relatives of Dick Justice." The advert resulted in a response from Bill Williamson who knew Justice's daughter, Ernestine Smith. Ernestine, who was in her late eighties at the time and still living in Logan, had a photograph of her father and dramatic stories of his life in the coal mines and his recording career. Bill Williamson revealed his father was the founder of another legendary group from the period, The Williamson Brothers.[32] Inspired by what he'd discovered, MacMahon began to pursue other musicians of interest from the era. His production partner Allison McGourty encouraged him to use this research for the basis of a film.[21] She reasoned that this would be the last opportunity to tell these stories before all the direct relatives and witnesses had died.[33] MacMahon, on embarking on this vast research expedition, commented that "almost a century later, we wanted to see if we could still experience that music directly, among the people who made it, in the places it was played. We started by choosing some artists and recordings that we found particularly moving, then set out to trace them through space and time. At times it seemed a quixotic quest, but as we traveled, we kept being startled by the overlaps of old and new, the ways in which the music of the past continued to resonate and reflect the present. We had left our home in twenty-first-century Britain to travel across a foreign country and deep into the past, but over and over again, the people we met and the places we visited felt very familiar and very much in the present."[28]

MacMahon and McGourty travelled extensively in 37 U.S. states for over 10 years researching the films.[34] Some performers, like the Breaux Frères, had been misrepresented for years by erroneous photographs[35] while others, like Elder J.E. Burch and the Hopi Indian Chanters, had no known photographs and no biographical information whatsoever.[7][36] These had to be found by carefully studying census records and recording ledgers, and by placing adverts in local papers to help locate living family members.[31][37] In the case of Burch, a solitary reference in a 1927 Victor Records recording ledger to Cheraw, South Carolina led the producers to travel to that town. When they arrived, they did not find anyone who remembered the preacher until they were introduced to Ted Bradley, a town elder who attended Burch's church as a boy in the 1930s.[12] Bradley took them to Burch's church and revealed that Burch had been an emancipatory figure in the town, helping found the local chapter of the NAACP and unifying the black and white townsfolk at a time of extreme segregation.[38] Bradley introduced them to another contemporary, Ernest Gillespie, who revealed that his cousin had lived next door to Burch's church and that Burch's music had inspired him to pursue a career in music. That cousin was Dizzy Gillespie, a major figure in the development of bebop and modern jazz and one of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time.[39][37] MacMahon researched other little-known musicians, like Joseph Kekuku, whom they confirmed to be the inventor of the Hawaiian steel guitar. They charted his journey from Oahu to the mainland and uncovered his touring itineraries which demonstrated how he had popularized that instrument throughout North America and Europe, resulting in it being incorporated into Delta blues, country, African Jùjú and even Pink Floyd.[40][41] One of the biggest challenges was that the first electrical recording equipment from 1925 that made the field recording sessions possible[4][26] had not been seen in almost 80 years.[42] This equipment had huge scientific and cultural significance,[5][29] as it was not only the origin of all modern electrical sound recording today, but also was used to record sound for the first talking pictures.[42][43]

The production's sound engineer, Nicholas Bergh, spent ten years rebuilding the recording equipment from parts scavenged from around the world[27] and the team located the first ever period images of the equipment from an archive of over 1,000,000 uncatalogued photos in the Western Electric archives. Most importantly, they located the rare film footage showing it in operation from a film collector in Belgium and a severely damaged reel in the British Film Institute.[35][44] MacMahon summarized the research, stating the "process wasn't all sunshine and smiles—we traveled to beautiful places and met some of the most wonderful people we have ever known, but we also heard stories of poverty and discrimination, of hard times and troubled lives. The power of the music comes in a large part from its role as a comfort and release for people trapped in difficult situations. But the journey was always rewarding, not despite, but because of those connections. As we traveled, the songs became less and less connected to old discs and vanished eras, and more and more to living people and communities."[37]

Production

[edit]Interviewees

[edit]MacMahon resolved to interview only direct family members and first-hand witnesses for the documentary series.[1][3][12][45] With the large amount of new and unpublished research in the films,[8] he deemed it would be inappropriate to interview historians as they would be ineffective commenting on stories that were entirely based on new research.[35] MacMahon also felt that the stories were the property of the family members, and it was their sole right to tell them.[35][46][47] Some of the interviewees were close to 100-years-old, and a number of them died shortly after filming.[48] MacMahon used every available archival interview with the performers themselves although filmed examples were extremely uncommon. Very rare archival audio interviews were used with key characters like Joe Falcon, Maybelle Carter, Will Shade, Ralph Peer and Frank Walker.[12] These required extensive restoration work by the audio team to render them usable for the film.[49] MacMahon remarked that the original ¼ inch tape of the Peer interview was "virtually unintelligible before Nick [Nicholas Bergh, sound engineer] got his hands on it, but it was vital for the audience to get a sense of this man's personality by any means possible."[35]

Filming

[edit]Each story begins with one of those old record albums which would hold anywhere between four and eight pockets that you would put your 78s into. The idea was 'How, without being didactic, does one capture this beautiful richness, and at the same time, acknowledge that however deeply you go into these stories, they are just one of thousands. So we thought, 'why don't we pull one of these albums of the shelf?'[50]

All filming for the series was done on location with interviewees shot in places of significance to each story – on the porch of Maybelle Carter's house in Maces Spring, Virginia for the Carter Family story;[12] in the building of the former Monarch Nightclub in Memphis, Tennessee for the Memphis Jug Band story;[51] and on the shores of Oahu for the Joseph Kekuku story.[27] The production involved extensive filming trips across 37 states[52] that producer Allison McGourty coordinated "from Cleveland, Ohio to the Gulf of Mexico, and from New York to Hawaii."[53] MacMahon determined a comprehensive anthology of the period was impossible within the time constraints of a documentary film series.[21] Mindful of the vast number of musicians who participated in these recording sessions, MacMahon decided to focus on eleven stories in detail to give the viewer an emotional connection to the musicians and their music, and to their culture and geographical surroundings.[10][54][55][56] He employed a creative device to demonstrate that the films were a selective exploration; each story began with a leather bound 78rpm record album, of the type used in the 20s, being opened to reveal sleeves containing the disc of the artist that would be the subject of the story, thereby indicating that this story was one of thousands in a vast library.[10] This technique is known as an anthology film. MacMahon said he took his inspiration for this approach from "one of my favorite films – Dead of Night."[35]

Cinematography

[edit]Extensive tracking shots were filmed of the landscape in each state and used as a device to demonstrate how much the geography influenced the music of the musicians in the 1920s. MacMahon explained, "As a filmmaker, I'm fascinated by how the eye informs the heart. Driving through these remote locations with the film crew, we would play the music from that area in the van and it was extraordinary how closely the melodies and rhythms reflected the terrain from which they sprung. I see music visually and I think it mirrors its environment perfectly. The music of the Hopi sounded otherworldly when I first heard it, but after traveling to the Hopi reservation and having the honor of being allowed to film there, I started humming their songs. 'Chant of the Eagle Dance' now sounds like a pop single to me."[7] He added, "Things sound like the place they're from, the music makes sense. You're never going to hear Miles Davis make more sense than listening to him in a New York cab, and the Carter Family will never make more sense than if you listen to the music, watching the farm scenes from the 1920s from right where they lived."[24] MacMahon coined the term "geographonics" for this phenomenon.[57] MacMahon went to great lengths to find the locations of old historic photographs related to the stories and made frequent use of dissolves between these old photographs and contemporary footage he shot to show the passage of time.[35] The interviews were all filmed using an Arri Alexa on a slider or a camera dolly. All the interviews and the occasional musical performances were storyboarded by MacMahon prior to filming.[58] "We set out to explore why particular recordings gave us particular feelings and touched particular emotions and found that an important part of that was the way they reflected particular communities and the particular geography of the places where those people lived. The more we traveled, the more we became convinced that sounds and styles arise from specific environments, and you can only truly understand them when you go where they came from. Of course, you can enjoy music without hearing it in its native setting, but we kept finding that we had never fully experienced a recording or felt it to the depth of our souls until we listened to it in its home."[54]

Editing

[edit]Dan Gitlin, the senior editor on the films, developed a pacing for the series in collaboration with director Bernard MacMahon to complement the leisurely speaking pace of the elderly interviewees.[35] MacMahon said when Robert Redford offered to narrate the film he knew it would match the editorial style. He described Redford's voice as "untainted but also very American" adding that "he has a very low-key, understated way of speaking that suits this film. His voice has no baggage but it has enormous gravitas; it sounds like Mount Rushmore."[24] MacMahon decided to showcase most of the archival music performances in their entirety. He said, "This technique was employed to allow the viewer to emotionally connect with unfamiliar music smoothly."[35] Intense research went into ensuring all the archival film clips and stills were from the correct location and time period of each story.[31] This technique was used to match the music with the landscapes that had inspired it.[30] All the archival film footage and stills were scanned at the highest possible resolution, and extensive restoration work was undertaken on hundreds of rare and damaged photographic stills.[5][20][52] Producer Allison McGourty explained that "it was really to do justice to the people themselves and the families, because for example when we found photos of Mississippi John Hurt or [the Tejano musician] Lydia Mendoza you want the public now to see them as they were then, which was beautiful. You don't want to see them in a raggedy old photograph, so we wanted to do justice to them and once you start doing [restoring] one, you have to do all of them."[59] MacMahon was dissatisfied with the contemporary methods of presenting archival film footage in documentaries and innovated a new technique to blend the 4:3 aspect ratio of the 1920s film footage[60] with the 16:9 aspect ratio of his contemporary footage. Traditionally the 4:3 footage had been either panned and scanned to fill the 16:9 screen, losing the top and bottom of the image, or reproduced intact with pillarboxing, resulting in black bars on either side of the frame.[60] To overcome this, MacMahon overscanned the nitrate film revealing the edges of the frame and created mattes out of scans of the black leader from the same film reel to create a 16:9 frame. This new technique, called "Epic Scans" gave a full-screen appearance to archival film clips without losing any of the images, allowing the viewer to experience these clips as they were originally intended but on a widescreen format without cropping or black bars.[52][61]

Sound

[edit]New sound restoration techniques were developed for the films and utilized to restore the recordings featured in the series.[21] The 78rpm disc transfers were made by sound engineer Nicholas Bergh, using reverse engineering techniques garnered from working with the first electrical recording system on The American Epic Sessions[62] along with meticulous sound restoration undertaken by Peter Henderson and Joel Tefteller to reveal greater fidelity, presence, and clarity to these 1920s and 1930s recordings than had been heard before.[10][62][63][64][65] Nicholas Bergh commented that the 1920s recordings "are special since they utilize the earliest and simplest type of electric recording equipment used for commercial studio work. As a result, they have an unrivaled immediacy to the sound."[9] Some of the recordings were repressed from the original metal parts, which the production located while researching the films.[66] Peter Henderson explained, "In some cases we were lucky enough to get some metal parts – that's the originals where they were cut to wax and the metal was put into the grooves and the discs were printed from those back in the '20s. Some of those still exist – Sony had some of them in their vaults"[65] The same care was taken in transferring and restoring the audio pulled from archival film clips, again using techniques and proprietary equipment devised by sound engineer Nicholas Bergh, who specializes in the restoration of audio tracks for the major Hollywood studios.[42] The films were mixed in mono to match the contemporary audio with the 1920s and 1930s recordings.[35]

Soundtracks and albums

[edit]The quality of the audio restoration of the recordings used in the film series inspired MacMahon, McGourty and Erikson to source the best surviving masters of over 169 songs from the period and reissue them on a series of nine compilations.[53] One compilation, American Epic: The Soundtrack, selected musical highlights from the American Epic films and five other compilations collected the best performances by some of the musicians profiled in the films. There was a country and blues compilation and a five CD 100 song box-set, American Epic: The Collection,[67] featuring one track by each of the hundred artists researched as potential subjects for the films.[68]

Book

[edit]A book documenting the 10 years of research and journeys across the United States to create the American Epic films was written by MacMahon, McGourty and Elijah Wald. American Epic: The First Time America Heard Itself was published on May 2, 2017, by Simon & Schuster.[69]

Reception

[edit]Release

[edit]The film was previewed as a work in progress at film festivals around the world throughout 2016, including a Special Event at Sundance hosted by Robert Redford,[70] International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam,[71] Denver International Film Festival,[72][73] Sydney Film Festival,[74] and the British Film Institute. The film was completed in February 2017 and aired on PBS in the US and BBC Four in the UK in May and June 2017. An NTSC DVD and Blu-ray of the series was released in the US on June 13, 2017.[67]

Critical reception

[edit]The films were released to widespread critical acclaim, with many publications praising the direction, cinematography, archive footage, research and the quality of the sound.[5][9][17][18][19][20][75]

Mike Bradley wrote in The Observer, "Bernard MacMahon's landmark documentary series is one of the most interesting music programs ever broadcast. It's hard to believe so much fascinating material can fit into one film. A gorgeous history lesson and exceptional television."[17] Randy Lewis in the Los Angeles Times described the films as "an extraordinary star-studded four-part music documentary exploring the birth of the recording industry and its impact on world culture"[3] Catherine Gee in The Daily Telegraph wrote, "This landmark three-part documentary from British director Bernard MacMahon brings us an evocative account of the birth of recorded music and the USA's cultural revolution."[76] Michael Watts in The Economist described the series as "an unmissable new trilogy of documentaries, [which] uncovers the origins of popular music. One of the strengths of the films is that they resurrect the forgotten and obscure. Hardly anyone remembers J.E. Burch, a preacher from South Carolina who, in 1927, recorded 11 tracks of 'sanctified' music with his church choir that presaged the rage for gospel. Fewer still know that he inspired another musical giant, Dizzy Gillespie, who was raised a block away from his church in the town of Cheraw."[19]

Iain Shedden in The Australian reported that "one of the highlights (and audience prize winner) of last year's Sydney Film Festival was the American Epic series of documentaries by British filmmaker Bernard MacMahon and producers Allison McGourty and Duke Erikson. It's an exquisite representation of the primitive power of American roots music and its enduring charm - music that stirs the soul."[77] Elizabeth Nelson in Men's Journal observed that "over the decades, many filmmakers have dealt with the rich and woolly topic of American roots music, but few have ever approached the ambition of the current three-part PBS documentary American Epic. An immersive and panoramic overview of American song in the 20th century, the film tramps an itinerant path throughout the roadhouses and juke joints of the rural South, the border towns of Texas and the Southwest, and eventually reaches as far as Hawaii. Abetted by the extraordinary vintage footage, much of it recently unearthed, American Epic offers fresh revelations regarding artists ranging from the iconic to the obscure, all the while stitching together the diverse quilt of regional and cultural influences into a coherent and stunning whole."[7]

Alain Constant reviewing the French broadcast in Le Monde wrote, "this documentary retraces with archive and testimonials the wonderful epic poem of country music, gospel, rhythm, and blues. American Epic is an ambitious project led by film director and producer Bernard MacMahon. His mission to trace the history of the origins of American popular music. The final result of this work co-produced with Arte, BBC Arena, and the ZDF, is impressive, with exceptional film and sound archives, as well as unpublished testimonies spread over three and a half hours."[78] Steve Appleford in Rolling Stone described the series as "The Lawrence of Arabia of music documentaries"[79] adding that "the goal was not simply to retell the Wikipedia version of the story. MacMahon and producer Allison McGourty spent a decade seeking original sources in the field, going from family to family. They discovered artifacts and previously unknown photographs of such originators as Son House, the Memphis Jug Band, and West Virginia mine workers the Williamson Brothers and Dick Justice."[79] Garth Cartwright in Songlines stated that "as a connoisseur of American music I'm constantly surprised by some of the musical treasure American Epic discovers and shares. Not least the Hopi Indian snake dance footage of a performance in front of the Capitol in Washington, DC in 1926, a stunning find."[75]

Phil Harrison in The Guardian wrote that "from the jug-bands of Memphis to the woebegone country blues of the Appalachian Mountains, early 20th-century America was full of unique musical forms developing in isolation. This first episode of a three-part series deals with the 1920s, the first decade during which these disparate yet analogous styles took flight from their places of origin and reached the rest of the nation. It's a treasure trove of picaresque stories, evocative footage and strange and beautiful music."[80] Jay Meehan in the Park Record, covering the launch at the Sundance Film Festival, wrote, "Thursday night's Sundance special event at the Eccles Center was one not to miss. One thing that came through quite clearly from the entire evening is how deeply everyone involved cares about this project."[81] Ellie Porter in TVTimes awarded the show 5 stars, calling the series "an absolute treat."[82] Brian McCollum in the Detroit Free Press noted that the films were "stocked with rare images and scrupulously restored audio,"[5] explaining how "American Epic solves mysteries, brings a lost musical era back to life."[5] He praised it as "a documentary which pairs a scholarly eye for detail with a buoyant fan passion."[5] Sarah Hughes in The Observer noted that Robert Redford's "languid tone is a perfect fit," and that "this three-part documentary is a deep dive into the music that built America. Along the way love is lost, younger generations step up to the mic and reputations fade, but, as this glorious film makes clear, the music is always there, still vibrant and vital despite the passing of the years."[83]

Joe Boyd in The Guardian praised the series as "remarkable ... American Epic, tells the story of how this existential moment for the music industry coincided with the arrival of electrical recording. Victor and Okeh Records' response to the crisis laid the groundwork for popular music as we know it today. Filmmakers Bernard MacMahon and Allison McGourty have focused on key individuals and archetypal stories, bringing the characters and times to life with great sensitivity and thoroughness. Here, we see the birth of 'race records' and country music, two strands of the fast-expanding record industry that converged, in 1954, with Elvis and rock 'n' roll. The series shows us how the record industry introduced America to its true self, selling hundreds of thousands of records in cities as well as in the sticks, and creating a worldwide taste for the rural roots of urban music. While the first three parts of the series delve into history, making up for the absence of live footage with great interviews and a stunning assemblage of photographs, the fourth crowns the achievement with something different. Miss it at your peril."[20] Jonathan Webster in Long Live Vinyl wrote, "An Anglo-American team of documentary filmmakers, led by producer Allison McGourty and director Bernard MacMahon, set out on an epic journey to explore the huge variety of folk, rural and rregional music recorded in the United States during the late 1920s, culminating in a magnificent BBC TV series called American Epic"[21] adding "with wins and nominations already earned at various film festivals, including Calgary and Sydney, it's a safe bet American Epic is going to carve a niche in the pantheon of TV's great documentaries."[21] Ben Sandmel in Know Louisiana pointed out that "instead of presenting a host of music experts as talking heads, American Epic takes a novel and commendably populist approach by interviewing descendants of the featured musicians, or people who actually knew them. The most effective use of this technique can be seen in a segment about Elder J. E. Burch, a deeply soulful gospel singer from Cheraw, South Carolina. In Cheraw, director Bernard McMahon interviewed an elderly man named Ted Bradley, who had been a member of Burch's congregation. The scene where Bradley sees a photo of Burch for the first time in seventy years is truly touching, and such moments stand among the series' greatest strengths."[45]

Daniel Johnson in The Courier-Mail concurred, noting that "one of the most touching moments in the series occurs when MacMahon and his team meet with an elderly man named Ted Bradley in the small town of Cheraw, South Carolina. In his youth, Bradley had been a member of musician and preacher Elder Burch's congregation, and when the American Epic team produced an old photo of Burch, Bradley's emotion is palpable. Similar scenes are repeated throughout the series and for MacMahon, being able to go to the sources, the places where the artists featured came from and where they wrote their songs, and talk to their descendants, gave him an even greater appreciation for the music."[24] David Brown in the Radio Times praised the series as "a deep loving look at the roots of American popular music"[84] noting, "There are dozens of lip-smacking clips in this series about America's formative music."[85] Ludovic Hunter-Tilney in the Financial Times wrote that "the project's scope is vast but its argument is simple" acknowledging how "exhaustive legwork and first-rate archive footage bolster the narrative. Relatives of long-dead musicians are tracked down while archivists bring to light the fieldwork of record label scouts and recording engineers. In a touching vignette, three bluesmen in their nineties reminisce about their great predecessor Charley Patton; each of the trios died soon after the interview was made."[48] He concluded, "Appearing at a time when the nation's lack of unity is starkly visible, American Epic makes for a beautifully presented, richly enjoyable fairy tale"[48] Matt Baylis in the Daily Express wrote, "In this sweeping, electrifying, Old Testament-style account of America's musical journey, it was fitting that the first chapter ended in Memphis, with a young man called Elvis Presley, whose sound merged the two kinds of lightning Peer had captured in his bottles. The rock of the mountains and the roll of the streets."[86]

Robert Lloyd in the Los Angeles Times praised the series as a "useful reminder that there is more to life than the noise coming from our capitals and cable news. Music may not save the world, but it unites us anyway. It can still knock holes in our prejudices, making way for open hearts and willing spirits. I don't mind telling you I got a little emotional watching this series, and you might too."[87] Robert Baird in Stereophile commented that "the films have a wise structure that uses a single tune by a single artist such as Tejano/conjunto legend Lydia Mendoza's 'Mal Hombre' as jumping-off point for a deep dive into that artist's life and career" and praised the sound commenting, "What's most interesting for audiophiles is the huge improvement in the quality of the sound coming from these 78 transfers, both in the film and especially in the 5-CD boxed set of the same name." He adds that "the resolution and level of detail on these CDs is audible and impressive."[9] Blair Jackson in Acoustic Guitar stated, "Be sure to check out the brilliant three-part documentary series American Epic. The story is masterfully told by director Bernard MacMahon, who artfully combines amazing archival footage, still photographs, vintage recordings, old and new interviews. Rather than attempting some sort of comprehensive historical narrative littered with endless names and factoids (Robert Redford is the series' calm and thoughtful narrator), MacMahon has chosen to focus on a few representative musicians from different genres to tell the tale in a more personal way. It's an approach that really brings the history to life. I can't recommend this series highly enough. It's constantly entertaining and inspiring, often moving (such as the section on Hopi Indian music), and full of surprises."[18]

The films have received a number of awards, including the Foxtel Audience Award at the 2016 Sydney Film Festival[88] and the Discovery Award at the 2016 Calgary International Film Festival,[14] and were nominated for a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Music Direction.[15] On April 23, 2018, the Focal International Awards nominated American Epic for Best Use of Footage in a History Feature, as well as Best Use of Footage in a Music Production.[89]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary International Film Festival | The Discovery Award | Bernard MacMahon | Won | [14] |

| Hawaii International Film Festival | Best Documentary | American Epic: Out of the Many, the One | Nominated | [90] |

| Primetime Emmy Award | Outstanding Music Direction | Bernard MacMahon, Duke Erikson, T Bone Burnett and Jack White | Nominated | [15] |

| Sydney Film Festival | Foxtel Audience Award | American Epic | Won | [13] |

| Tryon International Film Festival | Best Documentary | Bernard MacMahon | Won | [91] |

| Tryon International Film Festival | Best Overall Picture | Bernard MacMahon | Won | [91] |

| Focal International Awards | Best Use of Footage in a History Feature | American Epic | Nominated | [92] |

| Focal International Awards | Best Use of Footage in a Music Production | American Epic | Nominated | [92] |

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "BBC - Arena: American Epic - Media Centre". BBC. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b "About the Series – American Epic". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Randy (18 April 2017). "'American Epic' documentary on birth of recorded music to premiere May 16". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c "The Long-Lost, Rebuilt Recording Equipment That First Captured the Sound of America". WIRED. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "'American Epic' solves mysteries, brings lost musical era back to life". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ "PBS's 'American Epic' is a love letter to U.S. | TV Show Patrol". TV Show Patrol. 2017-04-18. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c d e "Mule Calls and Outlaws: A Conversation With 'American Epic' Director Bernard MacMahon". Men's Journal. 2017-05-23. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b "'American Epic' Recreates Music History With Elton John, Beck & More". uDiscoverMusic. 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c d "American Epic". Stereophile.com. 2017-06-12. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Randy (14 May 2017). "'American Epic' explores how a business crisis ignited a musical revolution". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, pp. 3-5

- ^ a b c d e "American Epic: How Jack White helped piece together the story of a nation's musical roots - Uncut". Uncut. 2017-04-21. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b Shedden, Iain (2017-07-14). "Stars out for American Epic". www.theaustralian.com.au. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ a b c "And the Winners are… | Calgary International Film Festival". www.calgaryfilm.com. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c "69th Emmy Awards Nominees and Winners - OUTSTANDING MUSIC DIRECTION - 2017". Television Academy. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ "Focal International Awards 2018" (PDF). Focal International Awards.

- ^ a b c Bradley, Mike (June 4, 2017). "Arena: American Epic". The Observer.

One of the most interesting programmes ever broadcast

- ^ a b c "Don't Miss PBS' Roots Music Documentary Series 'American Epic'!". Acoustic Guitar. 2017-05-15. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c "The first time America heard itself sing". 1843. 2017-05-20. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c d Boyd, Joe (2017-05-19). "How the record industry crisis of 1925 shaped our musical world". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g "American Epic - Reviving Record Production's Past". Long Live Vinyl. 2017-06-16. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^ a b c d "American Epic Episode Descriptions". PBS. 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ "A Love Letter to America: 'American Epic'". WTTW Chicago Public Media - Television and Interactive. 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Daniel (November 16, 2017). "English director, writer, producer and music fan Bernard MacMahon retraces the roots of American music in documentary series American Epic". www.couriermail.com.au. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b c American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, p. 119

- ^ a b c "PBS Series 'American Epic' Explores Our Musical Roots, With Help From Jack White & T Bone Burnett". Billboard. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b c "'American Epic': Inside Jack White and Friends' New Roots-Music Doc". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, p. 1

- ^ a b "A Love Letter to America: 'American Epic'". WTTW Chicago Public Media - Television and Interactive. 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, p. 3

- ^ a b c Robinson, Jennifer. "AMERICAN EPIC". KPBS Public Media. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, pp. 104-105

- ^ "PBS' American Epic debuts in May". OffBeat Magazine. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ Recordings, Legacy. "University of Chicago Laboratory Schools announce 9-month educational program based on the "American Epic" films, music and book". www.prnewswire.com (Press release). Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j MacMahon, Bernard (September 28, 2016). "An Interview with Bernard MacMahon". Breakfast Television (Interview). Interview with Jill Belland. Calgary: City

- ^ American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, p. 83

- ^ a b c American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, p. 92

- ^ American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, pp. 87-89

- ^ Foat, Lindsey (May 10, 2017). "'American Epic' Filmmakers Tell America's Untold Musical Story". KCPT. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ "What is American Epic and why was it made?". 2016-08-21. Archived from the original on 2018-02-10. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ Genegabus, Jason (May 14, 2017). "Revolution in blues, rock credited to isle musician". www.staradvertiser.com/. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Randy (21 July 2017). "Reinventing the machine that let America hear itself on the PBS-BBC doc 'American Epic'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ "SXSW review: 'The American Epic Sessions' | Austin Movie Blog". Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ "On PBS: American Epic - FAR-West". www.far-west.org. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b "America Hears Itself - Know Louisiana". Know Louisiana. 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ Anderson, John (2017-05-11). "'American Epic' Review: For the Record". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, p. 8

- ^ a b c Hunter-Tilney, Ludovic (May 19, 2017). "'American Epic': too much harmony?". Financial Times. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ "Restoring a vintage 1920s recording system for 'American Epic'". Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ "American Epic explores how a business crisis ignited a musical revolution". Los Angeles Times. 2017-05-13. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ [1] Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, pp. 50-51

- ^ a b c Armstrong, Nikki (February–March 2018). "American Epic". Big City Rhythm & Blues.

- ^ a b "An 'Epic' Journey | MaxTheTrax". maxthetrax.com. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ a b American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, pp. 4-5

- ^ Boyd, Joe (2017-05-19). "How the record industry crisis of 1925 shaped our musical world". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ "American Epic Highlights San Antonio - Online - May 2017". sanantoniomag.com. 24 May 2017. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, pp. 108-109

- ^ "SXSW '16: Reviving recording history in "American Epic"". Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ^ "'American Epic' Filmmakers Tell America's Untold Musical Story". KCPT. Retrieved 2018-02-13.

- ^ a b Kirby, Ben (5 January 2014). "Film Studies 101: A Beginner's Guide To Aspect Ratios". Empire. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ^ MacMahon, Bernard (October 7, 2018). "The Making of American Epic - 2018 Tryon International Film Festival". Tryon International Film Festival (Interview). Interview with Kirk Gollwitzer. 2018.11.14.

- ^ a b "'American Epic': Inside Jack White and Friends' New Roots-Music Doc". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ^ "Greil Marcus' Real Life Rock Top 10: The Epic Tradition". Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ^ Anderson, Ian (August 2017). "American Epic". fRoots. p. 59.

- ^ a b "Restoring a vintage 1920s recording system for 'American Epic'". Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ^ American Epic (documentary) Wald, McGourty, MacMahon 2017, p. 21

- ^ a b "American Epic: The Collection & The Soundtrack Out May 12th | Legacy Recordings". Legacy Recordings. 2017-04-28. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ Wald, Elijah; McGourty, Allison; MacMahon, Bernard; Bergh, Nicholas (2017). American Epic: The Collection (Liner note essay). Legacy / Lo-Max. ASIN B071RHDMB8.

- ^ MacMahon, Bernard; McGourty, Allison; Wald, Elijah (2017-05-02). American Epic. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781501135606.

- ^ "american-epic". www.sundance.org. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ www.oberon.nl, Oberon Amsterdam, American Epic: The Big Bang | IDFA, retrieved 2018-02-11

- ^ "American Epic: The Big Bang | Denver Film Society | Bernard MacMahon | USA". secure.denverfilm.org. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ "American Epic: Out of the Many One | Denver Film Society | Bernard MacMahon | USA". secure.denverfilm.org. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ "SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES SOUNDS ON SCREEN" (PDF). sff.org.au. June 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-18.

- ^ a b Cartwright, Garth (July 2017). "Made in the USA". Songlines. p. 40.

- ^ Gee, Catherine (May 20, 2017). "Digital Choice: American Epic". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 19, 2000.

- ^ Shedden, Iain (July 15, 2017). "Reviews: American Epic". The Australian.

- ^ "TV – " American Epic ", aux origines de la musique populaire aux Etats-Unis". Le Monde.fr (in French). January 2018. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ a b "'American Epic': Inside Jack White and Friends' New Roots-Music Doc". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ Mueller, Andrew; Stubbs, David; Verdier, Hannah; Seale, Jack; Harrison, Phil; Virtue, Graeme; Howlett, Paul (2017-05-21). "Sunday's best TV: Twin Peaks; The Trial: A Murder in the Family". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ "America's musical roots explored in new series". Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ Porter, Ellie (May 20–26, 2017). "American Epic". TVTimes. p. 41.

- ^ Hughes, Sarah (May 21, 2017). "TV Choice, Arena: American Epic". The Observer.

- ^ Brown, David (May 20–26, 2017). "Arena: American Epic". Radio Times.

- ^ Brown, David (May 27 – June 2, 2017). "Arena: American Epic". Radio Times.

- ^ Baylis, Matt (2017-05-22). "Last night's TV reviewed: The road to revolutions". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ Lloyd, Robert (15 May 2017). "PBS digs into roots music with 'American Epic'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

- ^ "63rd Sydney Film Festival Complete Foxtel Movies Audience Award Announced" (PDF). sff.org. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2018.

- ^ "Production Nominations". FOCAL INTERNATIONAL AWARDS. 2018-04-17. Archived from the original on 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ^ "Hawaii International Film Festival (2015)". IMDb. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ a b ""American Epic" filmmakers return to Tryon for special event - The Tryon Daily Bulletin". The Tryon Daily Bulletin. 2016-12-08. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ a b "Focal International Awards 2018" (PDF). Focal International Awards.

Bibliography

[edit]- Wald, Elijah & McGourty, Allison & MacMahon, Bernard. American Epic: The First Time America Heard Itself. New York: Touchstone, 2017. ISBN 978-1501135606.

External links

[edit]- Documentary film series

- 2017 television films

- English-language films

- Rockumentaries

- 2017 documentary films

- 2017 films

- 2017 in American television

- 2010s American documentary television series

- Documentary films about the music industry

- Documentary films about blues music and musicians

- Documentary films about country music and musicians

- 2010s British music television series

- 2010s British documentary television series

- Documentary television series about music

- Films directed by Bernard MacMahon (filmmaker)

- British musical documentary films