Heart transplantation

| Heart transplantation | |

|---|---|

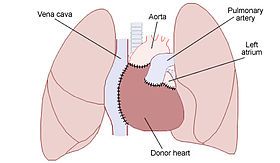

land illustrating the placement of a donor heart in an orthotopic procedure. Notice how the back of the patient's left atrium and great vessels are left in place. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| ICD-9-CM | 37.51 |

| MeSH | D016027 |

| MedlinePlus | 003003 |

A heart transplant, or a cardiac transplant, is a surgical transplant procedure performed on patients with end-stage heart failure or severe coronary artery disease when other medical or surgical treatments have failed. As of 2018[update], the most common procedure is to take a functioning heart, with or without both lungs, from a recently deceased organ donor (brain death is the standard[1]) and implant it into the patient. The patient's own heart is either removed and replaced with the donor heart (orthotopic procedure) or, much less commonly, the recipient's diseased heart is left in place to support the donor heart (heterotopic, or "piggyback", transplant procedure).

Approximately 3,500 heart transplants are performed each year worldwide, more than half of which are in the US.[2] Post-operative survival periods average 15 years.[3] Heart transplantation is not considered to be a cure for heart disease; rather it is a life-saving treatment intended to improve the quality and duration of life for a recipient.[4]

History

[edit]

American medical researcher Simon Flexner was one of the first people to mention the possibility of heart transplantation. In 1907, he wrote the paper "Tendencies in Pathology," in which he said that it would be possible one day by surgery to replace diseased human organs – including arteries, stomach, kidneys and heart.[5]

Not having a human donor heart available, James D. Hardy of the University of Mississippi Medical Center transplanted the heart of a chimpanzee into the chest of dying Boyd Rush in the early morning of Jan. 24, 1964. Hardy used a defibrillator to shock the heart to restart beating. This heart did beat in Rush's chest for 60 to 90 minutes (sources differ), and then Rush died without regaining consciousness.[6][7][8] Although Hardy was a respected surgeon who had performed the world's first human-to-human lung transplant a year earlier,[9][10] author Donald McRae states that Hardy could feel the "icy disdain" from fellow surgeons at the Sixth International Transplantation Conference several weeks after this attempt with the chimpanzee heart.[11] Hardy had been inspired by the limited success of Keith Reemtsma at Tulane University in transplanting chimpanzee kidneys into human patients with kidney failure.[12] The consent form Hardy asked Rush's stepsister to sign did not include the possibility that a chimpanzee heart might be used, although Hardy stated that he did include this in verbal discussions.[7][12][13] A xenotransplantation is the technical term for the transplant of an organ or tissue from one species to another.

Dr Dhaniram Baruah of Assam, India was the first heart surgeon to transplant a pig's heart in human body.[14] However the recipient died subsequently. The world's first successful pig-to-human heart transplant was performed in January 2022 by surgeon Bartley P. Griffith of USA.[15]

The world's first human-to-human heart transplant was performed by South African cardiac surgeon Christiaan Barnard utilizing the techniques developed by American surgeons Norman Shumway and Richard Lower.[16][17] Patient Louis Washkansky received this transplant on December 3, 1967, at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. Washkansky, however, died 18 days later from pneumonia.[16][18][19]

On December 6, 1967, at Maimonides Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, Adrian Kantrowitz performed the world's first pediatric heart transplant.[16][20] The infant's new heart stopped beating after 7 hours and could not be restarted. At a following press conference, Kantrowitz emphasized that he did not consider the operation a success.[21]

Norman Shumway performed the first adult heart transplant in the United States on January 6, 1968, at the Stanford University Hospital.[16] A team led by Donald Ross performed the first heart transplant in the United Kingdom on May 3, 1968.[22] These were allotransplants, the technical term for a transplant from a non-genetically identical individual of the same species. Brain death is the current ethical standard for when a heart donation can be allowed.

Worldwide, more than 100 transplants were performed by various doctors during 1968.[23] Only a third of these patients lived longer than three months.[24]

The next big breakthrough came in 1983 when cyclosporine entered widespread usage. This drug enabled much smaller amounts of corticosteroids to be used to prevent many cases of rejection (the "corticosteroid-sparing" effect of cyclosporine).[25]

On June 9, 1984, "JP" Lovette IV of Denver, Colorado, became the world's first successful pediatric heart transplant. Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center surgeons transplanted the heart of 4-year-old John Nathan Ford of Harlem into 4-year-old JP a day after the Harlem child died of injuries received in a fall from a fire escape at his home. JP was born with multiple heart defects. The transplant was done by a surgical team led by Dr. Eric A. Rose, director of cardiac transplantation at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. Drs. Keith Reemtsma and Fred Bowman also were members of the team for the six-hour operation.[26]

In 1988, the first "domino" heart transplant was performed, in which a patient in need of a lung transplant with a healthy heart would receive a heart-lung transplant, and their original heart would be transplanted into someone else.[27]

Worldwide, about 3,500 heart transplants are performed annually. The majority of these are performed in the United States (2,000–2,300 annually).[2] Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, currently is the largest heart transplant center in the world, having performed 132 adult transplants in 2015 alone.[28] About 800,000 people have NYHA Class IV heart failure symptoms indicating advanced heart failure.[29] The great disparity between the number of patients needing transplants and the number of procedures being performed spurred research into the transplantation of non-human hearts into humans after 1993. Xenografts from other species and artificial hearts are two less successful alternatives to allografts.[3]

The ability of medical teams to perform transplants continues to expand. For example, Sri Lanka's first heart transplant was successfully performed at the Kandy General Hospital on July 7, 2017.[30] In recent years, donor heart preservation has improved and Organ Care System is being used in some centers in order to reduce the harmful effect of cold storage.[31]

During heart transplant, the vagus nerve is severed, thus removing parasympathetic influence over the myocardium. However, some limited return of sympathetic nerves has been demonstrated in humans.[32]

Recently, Australian researchers found a way to give more time for a heart to survive prior to the transplant, almost double the time.[33] Heart transplantation using donation after circulatory death (DCD) was recently adopted and can help in reducing waitlist time while increasing transplant rate.[34] Critically ill patients that are unsuitable for heart transplantation can be rescued and optimized with mechanical circulatory support, and bridged successfully to heart transplantation afterwards with good outcomes.[35]

On January 7, 2022, David Bennett, aged 57, of Maryland became the first person to receive a gene-edited pig heart in a transplant at the University of Maryland Medical Center. Before the transplant, David was unable to receive a human heart due to the patient's past conditions with heart failure and an irregular heartbeat, causing surgeons to use the pig heart that was genetically modified.[36][37] Bennett died two months later at University of Maryland Medical Center on March 8, 2022.[38][39]

Contraindications

[edit]Some patients are less suitable for a heart transplant, especially if they have other circulatory conditions related to their heart condition. The following conditions in a patient increase the chances of complications.[40]

Absolute contraindications:

- Irreversible kidney, lung, or liver disease[41]

- Active cancer if it is likely to impact the survival of the patient

- Life-threatening diseases unrelated to the cause of heart failure, including acute infection or systemic disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis

- Vascular disease of the neck and leg arteries.

- High pulmonary vascular resistance – over 5 or 6 Wood units.

Relative contraindications:

- Insulin-dependent diabetes with severe organ dysfunction

- Recent thromboembolism such as stroke

- Severe obesity

- Age over 65 years (some variation between centers) – older patients are usually evaluated on an individual basis.

- Active substance use disorder, such as alcohol, recreational drugs or tobacco smoking (which increases the chance of lung disease)

Patients who are in need of a heart transplant but do not qualify may be candidates for an artificial heart[2] or a left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Complications

[edit]Potential complications include:[43]

- Post-operative complications include infection and sepsis. The surgery death rate was 5–10% in 2011.[44]

- Acute or chronic graft rejection

- Atrial arrhythmia

- Lymphoproliferative malignancies, further worsened by immunosuppressive medication[verification needed]

- Increased risk of secondary infections due to immunosuppressive medication

- Serum sickness due to anti-thymocyte globulin

- Tricuspid valve regurgitation

- Repeated endomyocardial biopsy can cause bleeding and thrombosis [45]

Rejection

[edit]Since the transplanted heart originates from another organism, the recipient's immune system will attempt to reject it regardless if the donor heart matches the recipient's blood type (unless if the donor is an isograft). Like other solid organ transplants, the risk of rejection never fully goes away, and the patient will be on immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of their life. Usage of these drugs may cause unwanted side effects, such as an increased likelihood of contracting secondary infections or develop certain types of cancer. Recipients can acquire kidney disease from a heart transplant due to the side effects of immunosuppressant medications. Many recent advances in reducing complications due to tissue rejection stem from mouse heart transplant procedures.[46]

People who have had heart transplants are monitored in various ways to test for possible organ rejection.[47]

A 2022 pilot study[48] examining the acceptability and feasibility of using video directly observed therapy to increase medication adherence in adolescent heart transplant patients showed promising results of 90.1% medication adherence compared to 40-60% typically. Higher medication variability levels can lead to greater organ rejections and other poor outcomes.

Prognosis

[edit]The prognosis for heart transplant patients following the orthotopic procedure has improved over the past 20 years, and as of June 5, 2009 the survival rates were:[49]

- 1 year: 88.0% (males), 86.2% (females)

- 3 years: 79.3% (males), 77.2% (females)

- 5 years: 73.2% (males), 69.0% (females)

In 2007, researchers from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine discovered that "men receiving female hearts had a 15% increase in the risk of adjusted cumulative mortality" over five years compared to men receiving male hearts. Survival rates for women did not significantly differ based on male or female donors.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kilic A, Emani S, Sai-Sudhakar CB, Higgins RS, Whitson BA, et al. (2014). "Donor selection in heart transplantation". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 6 (8): 1097–1104. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.03.23. PMC 4133543. PMID 25132976.

- ^ a b c Cook JA, Shah KB, Quader MA, et al. (2015). "The total artificial heart". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (12): 2172–80. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.70. PMC 4703693. PMID 26793338.

- ^ a b Till Lehmann (director) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ^ Burch M.; Aurora P. (2004). "Current status of paediatric heart, lung, and heart-lung transplantation". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 89 (4): 386–89. doi:10.1136/adc.2002.017186. PMC 1719883. PMID 15033856.

- ^ May Transplant the Human Heart (.PDF), The New York Times, January 2, 1908.

- ^ Hardy James D.; Chavez Carlos M.; Kurrus Fred D.; Neely William A.; Eraslan Sadan; Turner M. Don; Fabian Leonard W.; Labecki Thaddeus D. (1964). "Heart Transplantation in Man". JAMA. 188 (13). doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03060390034008.

- ^ a b Every Second Counts: The Race to Transplant the First Human Heart, Donald McRae, New York: Penguin (Berkley/Putnam), 2006, Ch. 7 "Mississippi Gambling", pp. 123–27. This source states the heartbeat for approximately one hour.

- ^ James D. Hardy, 84, Dies; Paved Way for Transplants, Obituary, New York Times (Associated Press), Feb. 21, 2003. This source states the transplanted chimpanzee heartbeat for 90 minutes.

- ^ Hardy James D (1963). "Lung Homotransplantation in Man". JAMA. 186 (12): 1065–74. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.63710120001010. PMID 14061414. See also Griscom NT (1963). "Lung Transplantation". JAMA. 186 (12): 1088. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03710120070015. PMID 14061420. in same issue.

- ^ Second Wind: Oral Histories of Lung Transplant Survivors, Mary Jo Festle, Palgrave MacMillan, 2012.

- ^ Every Second Counts, McRae, page 126, top.

- ^ a b Cooper DK (2012). "A brief history of cross-species organ transplantation". Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 25 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1080/08998280.2012.11928783. PMC 3246856. PMID 22275786. ' … the consent form for Hardy's operation – which, in view of the patient's semi-comatose condition, was signed by a close relative – stipulated that no heart transplant had ever been performed, but made no mention of the fact that an animal heart might be used for the procedure. Such was the medicolegal situation at that time that this "informed" consent was not considered in any way inadequate. . '

- ^ Xenotransplantation: Law and Ethics, Sheila McLean, Laura Williamson, University of Glasgow, UK, Ashgate Publishing, 2005, p. 50.

- ^ "Pig Heart Transplanted in Human". The Hindu. 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ^ "Man Gets Genetically Modified Pig Heart". BBC. 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ^ a b c d McRae, D. (2006). Every Second Counts: The Race to Transplant the First Human Heart, New York: Penguin (Berkley/Putnam).

- ^ Norman Shumway: Father of heart transplantation who also performed the world's first heart-lung transplant, Obituary, The Independent [UK], 16 Feb. 2006.

- ^ "Memories of the Heart". Daily Intelligencer. Doylestown, Pennsylvania. November 29, 1987. p. A–18.

- ^ "Pneumonia Blamed in Transplant Patient's Death". The New York Times. 1967-12-21. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- ^ Lyons, Richard D. "Heart Transplant Fails to Save 2-Week-old Baby in Brooklyn; Heart Transplant Fails to Save Baby Infants' Surgery Harder Working Side by Side Gives Colleague Credit", The New York Times, December 7, 1967. Accessed November 19, 2008.

- ^ Heart: An American Medical Odyssey, Dick Cheney, Richard B. Cheney, Jonathan Reiner, MD, with Liz Cheney, Scribner (division of Simon & Schuster), 2013. "Three days later, on December 6, 1967, Dr. Adrian Kantrowitz"

- ^ Tilli Tansey; Lois Reynolds, eds. (1999). Early heart transplant surgery in the UK. Wellcome Witnesses to Contemporary Medicine. History of Modern Biomedicine Research Group. ISBN 978-1-84129-007-2. OL 12568266M. Wikidata Q29581627.

- ^ Major Medical Milestones Leading Up To the First Human Heart Transplantation Archived 2016-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, Kate Elzinga, from Proceedings of the 18th Annual History of Medicine Days Conference 2009: The University of Calgary Faculty of Medicine, Alberta, Canada, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011. " . . following Barnard's landmark heart transplantation on December 3, 1967, 107 human heart transplants were performed by 64 surgical teams in 24 countries in 1968. . "

- ^ The Adrian Kantrowitz Papers, Replacing Hearts: Left Ventricle Assist Devices and Transplants, 1960–1970, National Institutes of Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Transplantation of the heart: An overview of 40 years' clinical and research experience at Groote Schuur Hospital and the University of Cape Town, South African Medical Journal, "Part I. Surgical experience and clinical studies." J Hassoulas, Vol. 102, No. 6 (2012).

- ^ "Talk About a Guy With a Lot of Heart 1st kid to get new ticker wants to be doc" NY Daily News, 13 April 2003

- ^ Raffa, G.M.; Pellegrini, C.; Viganò, M. (November 2010). "Domino Heart Transplantation: Long-Term Outcome of Recipients and Their Living Donors: Single Center Experience". Transplantation Proceedings. 42 (9): 3688–93. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.09.002. PMID 21094839.

- ^ "SRTR – Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients". www.srtr.org. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- ^ Reiner Körfer (interviewee) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ^ First ever heart transplant in Sri Lanka successful, Hiru News, 9 July 2017.

- ^ Verzelloni Sef, A; Sef, D; Garcia Saez, D; Trkulja, V; Walker, C; Mitchell, J; McGovern, I; Stock, U (1 August 2021). "Heart Transplantation in Adult Congenital Heart Disease with the Organ Care System Use: A 4-Year Single-Center Experience". ASAIO Journal. 67 (8): 862–868. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000001482. ISSN 1058-2916. PMID 34039886. S2CID 235217756.

- ^ Arrowood, James A.; Minisi, Anthony J.; Goudreau, Evelyne; Davis, Annette B.; King, Anne L. (1997-11-18). "Absence of Parasympathetic Control of Heart Rate After Human Orthotopic Cardiac Transplantation". Circulation. 96 (10): 3492–98. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.10.3492. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 9396446.

- ^ Woods, Emily (2021-10-11). "Donor hearts given longer life under trial". The Canberra Times. Australian Associated Press.

- ^ Kwon, JH; Usry, B; Hashmi, ZA; Bhandari, K; Carnicelli, AP; Tedford, RJ; Welch, BA; Shorbaji, K; Kilic, A (28 July 2023). "Donor utilization in heart transplant with donation after circulatory death in the United States". American Journal of Transplantation. 24 (1): 70–78. doi:10.1016/j.ajt.2023.07.019. PMID 37517554. S2CID 260296589.

- ^ Sef, D; Mohite, P; De Robertis, F; Verzelloni Sef, A; Mahesh, B; Stock, U; Simon, A (September 2020). "Bridge to heart transplantation using the Levitronix CentriMag short-term ventricular assist device". Artificial Organs. 44 (9): 1006–1008. doi:10.1111/aor.13709. PMID 32367538. S2CID 218506853.

- ^ "In 1st, US surgeons transplant pig heart into human patient". Associated Press. 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "In a First, Man Receives a Heart From a Genetically Altered Pig". The New York Times. 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "Man given genetically modified pig heart dies". BBC News. 9 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Rabin, Roni Caryn (2022-03-09). "Patient in Groundbreaking Heart Transplant Dies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ de Jonge, N.; Kirkels, J. H.; Klöpping, C.; Lahpor, J. R.; Caliskan, K.; Maat, A. P. W. M.; Brügemann, J.; Erasmus, M. E.; Klautz, R. J. M.; Verwey, H. F.; Oomen, A.; Peels, C. H.; Golüke, A. E. J.; Nicastia, D.; Koole, M. A. C. (2008). "Guidelines for heart transplantation". Netherlands Heart Journal. 16 (3): 79–87. doi:10.1007/BF03086123. ISSN 1568-5888. PMC 2266869. PMID 18345330.

- ^ Sai Kiran Bhagra; Stephen Pettit; Jayan Parameshwar (2019), "Cardiac transplantation: indications, eligibility and current outcomes", Heart, 105 (3), British Medical Journal: 252–260, doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313103, PMID 30209127, S2CID 52194404

- ^ Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, Semigran MJ, Uber PA, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: A 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016 Jan. 35 (1):1–23.

- ^ Ludhwani, Dipesh; Fan, Ji; Kanmanthareddy, Arun (2020). "Heart Transplantation Rejection". StatPearls [Internet]. PMID 30725742. Retrieved 25 June 2020 – via NCBI Bookshelf. Last Update: December 23, 2019.

- ^ Jung SH, Kim JJ, Choo SJ, Yun TJ, Chung CH, Lee JW (2011). "Long-term mortality in adult orthotopic heart transplant recipients". J. Korean Med. Sci. 26 (5): 599–603. doi:10.3346/jkms.2011.26.5.599. PMC 3082109. PMID 21532848.

- ^ Rizk J, Mehra MR. Anticoagulation management strategies in heart transplantation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(3):210–18. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2020.02.002

- ^ Bishay R (2011). "The 'Mighty Mouse' Model in Experimental Cardiac Transplantation". Hypothesis. 9 (1): e5.

- ^ Costanzo MR, Dipchand A, Starling R, Anderson A, Chan M, Desai S, Fedson S, Fisher P, et al. (2010). "The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients". The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 29 (8): 914–56. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.034. PMID 20643330.

- ^ Killian, Michael O.; Clifford, Stephanie; Lustria, Mia Liza A.; Skivington, Gage L.; Gupta, Dipankar (2022-04-18). "Directly observed therapy to promote medication adherence in adolescent heart transplant recipients". Pediatric Transplantation. 26 (5): e14288. doi:10.1111/petr.14288. ISSN 1397-3142. PMID 35436376. S2CID 248242427.

- ^ Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2012 Update The American Heart Association. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Weiss, E. S.; Allen, J. G.; Patel, N. D.; Russell, S. D.; Baumgartner, W. A.; Shah, A. S.; Conte, J. V. (2009). "The Impact of Donor-Recipient Sex Matching on Survival After Orthotopic Heart Transplantation: Analysis of 18 000 Transplants in the Modern Era". Circulation: Heart Failure. 2 (5): 401–08. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.844183. PMID 19808369.