Allergies in children

| Allergy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Allergic diseases |

| |

| Hives are a common allergic symptom | |

| Specialty | Allergy and immunology |

| Symptoms | Red eyes, itchy rash, runny nose, shortness of breath, swelling, sneezing |

| Types | Hay fever, food allergies, atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma, anaphylaxis |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, skin prick test |

| Differential diagnosis | Food intolerances, food poisoning |

| Prevention | Repeated exposure to allergens, prophylactic respiratory medications |

| Treatment | Avoiding known allergens, medications, allergen immunotherapy |

| Medication | Steroids, antihistamines, epinephrine |

Allergies in children, an incidence which has increased over the last fifty years, are overreactions of the immune system often caused by foreign substances or genetics that may present themselves in different ways.[1] There are multiple forms of testing, prevention, management, and treatment available if an allergy is present in a child. In some cases, it is possible for children to outgrow their allergies.

Children affected by allergies in the developed world:[2]

- 1 in 13 have eczema

- 1 in 8 have allergic rhinitis

- 3-6% are affected by food allergy

Children in the United States under 18 years of age:[3]

- Percent with any allergy: 27.2%

- Percent with seasonal allergy: 18.9%

- Percent with eczema: 10.8%

- Percent with food allergy: 5.8%

Children in the United Kingdom:[2]

- 1 in 6 with eczema

- 1 in 5 with allergic rhinitis

- 7.1% of breast-fed infants who develop food allergies

Pathophysiology

[edit]A child's allergy is an immune system reaction to a foreign substance, or allergen, that is considered harmless to most. According to Dr. James Fernandez with the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University, "Genetic and environmental factors work together to contribute to the development of allergies."[4] Upon contact with an allergen, a child’s immune system produces antibodies which patrol the body for future encounters with the invader.[5] During any future encounters, the antibodies release immune system chemicals, such as histamine, that cause allergy symptoms in the nose, lungs, throat, sinuses, ears, eyes, skin, or stomach lining.[5][6] The development and symptoms of asthma can also be triggered by allergies; indoor allergens and indoor volatile organic compounds, such as formaldehyde, have been known to do so.[6][7][8][9] Anthony Durmowicz, M.D., a pediatric pulmonary doctor at the FDA also says that, if a child has both allergies and asthma, "not controlling the allergies can make asthma worse."[6]

Risk Factors

[edit]Children are already at a higher risk of developing an allergy due to their age.[5] Other risk factors include:[5][10][11]

- Having a family history of allergies or asthma

- Having asthma or other allergies/allergic conditions

Causes/Allergens

[edit]

Airborne allergens, certain foods, insect stings, medications, and latex or other substances one touches are the most common allergy triggers.

Examples of airborne allergens include:[5][11]

- Pollen

- Animal dander

- Dust mites

- Mold

- Cockroaches

The top 9 food allergens are:[12]

- Milk

- Eggs

- Fish

- Crustacean Shellfish

- Tree Nuts

- Peanuts

- Wheat

- Soybean

- Sesame

Vitamin D deficiency at the time of birth and exposure to egg white, milk, peanut, walnut, soy, shrimp, cod fish, and wheat makes a child more susceptible to allergies.[1] Soy-based infant formula is associated with allergies in infants.[13]

Common drug allergens in children are:[14]

- Amoxicillin (most common)

- Penicillin

- Other penicillin-based antibiotics

The most common insect bite/sting allergens are:[15][16]

- Bees

- Wasps

- Ants

- Mosquitoes

- Fleas

- Ticks

Common skin allergens and triggers include:[5][17][11][16]

- Latex

- Chemicals (cleaning products, fragrances, laundry detergents)

- Formaldehyde

- Plants

- Heat & cold

- Excessive sweating

- Stress & anxiety

- Infections

Signs/Symptoms

[edit]According to the Mayo Clinic, “Allergy symptoms, which depend on the substance involved, can affect your airways, sinuses and nasal passages, skin, and digestive system.”[5] The severity of the following symptoms varies from child to child.[5]

The symptoms of indoor and outdoor allergies in children may include:[18][19]

- Runny nose

- Itchy, watery eyes

- Sneezing

- Itchy nose or throat

- Nasal congestion

Symptoms of indoor allergies can occur year-round but tend to be more troublesome during the winter months when children are inside more often.[18] However, outdoor allergies, or seasonal allergies, normally change with the season.[19]

The potential symptoms of a food allergy include:[10][5]

- Tingling/itching in the mouth

- Swelling of the lips, tongue, face, throat, or other body parts

- Hives, itching, or eczema

- Abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting

- Anaphylaxis (life-threatening)

Possible symptoms of a drug allergy include:[5]

- Hives

- Itchy skin

- Rash

- Facial swelling

- Wheezing

- Anaphylaxis

Symptoms of a potential insect bite/sting allergy include:[5]

- A large area of swelling (edema) at the bite/sting site

- Itching or hives all over the body

- Cough, chest tightness, wheezing or shortness of breath

- Anaphylaxis

Symptoms of allergic skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, or eczema, include:[5]

- Itching

- Redness

- Flaking

Diagnosis

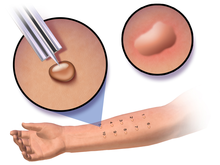

[edit]There are some different ways that can lead allergists to an official diagnosis of an allergy. These methods include:[5][10][4]

- Family history of allergies

- A diary with potential triggers or foods the child eats and reactions to them

- Elimination diet

- Skin tests (skin prick test and intradermal test)

- Blood test (allergen-specific serum IgE test)

- Provocative testing (oral food challenge, etc.)

Family medical history can be used to help determine if a child may have an allergy because of genetics. "Genes are thought to be involved because specific mutations are common among people with allergies and because allergies tend to run in families."[4] However, it is not the specific allergies that are passed down, just the likelihood of developing allergies.[11]

Keeping a diary of the child’s symptoms and possible triggers can help an allergist determine if the child has an allergy or guide decisions for further testing. The possible allergens tracked in this manner include food, skin, indoor and outdoor allergens. Keeping track of when the symptoms appear/the reaction occurs can also help determine the possible triggers, as "[f]ood allergy symptoms usually develop within minutes to 2 hours after eating the offending food."[10]

An elimination diet involves complete avoidance of suspected food allergens for 1–2 weeks and readding them to the child’s diet one at a time to watch for symptoms.[10] This method, however, may not always be accurate in identifying food allergies because it also works for determining food sensitivities/intolerances, which are different.[10]

There are two types of skin tests that are commonly used for diagnosing allergies. The first one done is the skin prick test, which can identify most allergens.[4] This test involves pricking a needle through a drop of each control and allergen test solutions into the child’s skin.[4] The intradermal test may be done second if no allergen is identified with the skin prick test.[4] This test is more sensitive and involves injecting tiny amounts of the control and allergen test solutions into the child’s skin with a needle.[4] For either test, any allergies will result with a wheal and flare reaction (swelled center and surrounding circular red area) at the pinprick site.[4] For accurate results, any child undergoing either test will need to stop taking any drugs/medications that may suppress a reaction.[4]

For children who cannot receive either skin test, the blood test is used to determine "whether IgE in the person's blood binds to the specific allergen used for the test."[4] IgE is immunoglobulin E – the antibody produced by the immune system to protect the body from the "invader."[11] A specific allergy can be confirmed if binding occurs with that allergen.[4] Provocative testing for any type of allergen involves directly exposing the child to small but increasing amounts of a suspected allergen.[4][10] It is done at a doctor’s office by a doctor who can confirm the allergy if a reaction occurs during the test.[10]

Provocative testing for any type of allergen involves directly exposing the child to small but increasing amounts of a suspected allergen.[4][10] It is done at a doctor’s office by a doctor who can confirm the allergy if a reaction occurs during the test.[10]

Prevention, Management, & Treatments

[edit]

There is no cure for allergies, making the avoidance of allergens one of the most important ways to prevent a reaction.[5] Keeping a diary of symptoms, potential triggers, activities, and what helps reduce symptoms is also a helpful form of prevention and management.[10][5]

For pet allergies, it may help to keep pet-free zones in the house (bedrooms), give furry friends frequent baths, have kids wash hands after petting and avoid touching their eyes, and use over-the-counter (OTC) allergy medicine to reduce symptoms.[18] These OTC allergy medications include antihistamines, such as Benadryl, Claritin, and Allegra, and nasal corticosteroids, such as Flonase and Afrin.[20] However, it is important to consult a doctor before taking any new medications. OTC medications may not work for every child, but a doctor may be able to prescribe a different, stronger medication or alternative treatment.[6] Immunotherapy in the form of allergy shots is one alternative treatment.[6] If the child’s reactions cannot be maintained using these methods, it may be better to find a new home for the pet and get a different one.

For other indoor allergies, thoroughly clean the house, bedding, and stuffed animals frequently.[18] Using special hypoallergenic furniture and covers for bedding, trading carpet for hardwood flooring, dehumidifying, and letting in sunlight may also help with some allergens.[18] If present, cockroaches, mice, and rats should be controlled to reduce symptoms as well.

Outdoor allergy symptoms can be managed by strategically planning outdoor play time, removing shoes and clothes and bathing after playing outside, keeping car and house windows closed and using the air conditioning, planting an allergy-friendly yard for kids, and keeping allergy medicine handy.[6][19] It may also help to keep leaves and grass clippings away from the house, keep trees and bushes trimmed, and avoid drying clothes on outdoor clotheslines.[6][19] Allergy shots are another possible means of management/treatment for these allergies as well, if necessary.[6]

Reactions to food allergens can also be prevented in multiple ways. One of these ways is avoiding cross contamination of allergens into safe foods.[10] Keeping hands/gloves, utensils, surfaces, etc. clean is important. Another effective way to avoid these allergens is to read food labels on everything that has one that may be ingested.[10] If a product contains or may contain one of the major nine allergens, the food labels are required to have a special note to inform potential consumers.[10] Other preventative measures include informing the child, relatives, babysitters, teachers, and any other care givers of the child’s allergy and ways to avoid/treat it and avoiding any foods that you are unsure of that were made by others.[11][10] This could be food at school, a restaurant, or any social gathering.[10]

For bug bite/sting and skin allergens, using fragrance-free skincare products, keeping the skin moisturized, using insect repellent, and wearing protective clothing are some of the easiest ways to prevent a reaction.[16] OTC medications, prescription (steroid) medications and creams, allergy shots, and biologics are also effective ways to manage/treat some skin allergies.[5][4][21] It is also best to avoid scratching any affected area(s) as much as possible.[16]

As they get older, some children may outgrow their allergies.[10] Others can also be desensitized to an allergen through exposure to the allergen, but this is a process that takes time and is not always necessary or possible.[4]

Severe Allergies & Reactions

[edit]If a child has any severe allergies that may be life-threatening, the Mayo Clinic recommends having the child wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace that would inform others of the allergy if the child was ever unable to communicate.[5] It is also crucial to always have an epinephrine auto-injector (EpiPen, etc.) on hand that is not expired.[5] Antihistamine medications are also helpful.[4]

If the child encounters the allergen and shows signs of anaphylaxis, use the epinephrine auto-injector first, if available, and seek medical help immediately. Antihistamine medication can also help slow the reaction in addition to epinephrine if it has been approved for combination by your doctor.[4] Otherwise, call 911 or your other local emergency number immediately for emergency medical help.[5]

Epidemiology

[edit]- Up to 5% of infants that are fed cow's milk-based formula will develop an allergy to cow's milk.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Stallings, Virginia A.; Oria, Maria P. (2017). Finding a Path to Safety in Food Allergy: Assessment of the Global Burden, Causes, Prevention, Management, and Public Policy. doi:10.17226/23658. ISBN 978-0-309-45031-7. PMID 28609025.

- ^ a b "Allergy in Children". BSACI. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "Allergies". CDC. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Fernandez, James. "Overview of Allergic Reactions". Merck Manuals. Merck. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Allergies". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Allergy Relief for Your Child". United States Food and Drug Administration. 1 June 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Ahluwalia, SK; Matsui, EC (April 2011). "The indoor environment and its effects on childhood asthma". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 11 (2): 137–43. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283445921. PMID 21301330. S2CID 35075329.

- ^ Rao, D; Phipatanakul, W (October 2011). "Impact of environmental controls on childhood asthma". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 11 (5): 414–20. doi:10.1007/s11882-011-0206-7. PMC 3166452. PMID 21710109.

- ^ McGwin, G; Lienert, J; Kennedy, JI (March 2010). "Formaldehyde exposure and asthma in children: a systematic review". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (3): 313–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901143. PMC 2854756. PMID 20064771.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Food Allergy". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Kids and Allergies". Johns Hopkins. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Food Allergies". FDA. 10 January 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Nowak-Węgrzyn, Anna; Katz, Yitzhak; Mehr, Sam Soheil; Koletzko, Sibylle (1 May 2015). "Non–IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergy". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 135 (5): 1114–1124. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.025. PMID 25956013.

- ^ Norton, Allison; Konvinse, Katherine; Phillips, Elizabeth; Broyles, Ana (1 May 2018). "Antibiotic Allergy in Pediatrics". Pediatrics. 141 (5): e20172497. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2497. PMC 5914499. PMID 29700201. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Tan, John W; Campbell, Dianne E (September 2013). "Insect allergy in children: Insect allergy". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 49 (9): E381 – E387. doi:10.1111/jpc.12178. PMID 23586469. S2CID 44313892.

- ^ a b c d "What Are the Main Triggers for Kid's Allergies? | Allegra". www.allegra.com. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Formaldehyde in Your Home: What you need to know | Formaldehyde and Your Health | ATSDR". www.atsdr.cdc.gov. 26 October 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Children's Indoor Allergies". Claritin. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Children's Outdoor Seasonal Allergies". Claritin. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Allergy Tips". www.aap.org. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Keyser, Heather; Chipps, Bradley; Dinakar, Chitra (1 November 2021). "Biologics for Asthma and Allergic Skin Diseases in Children". Pediatrics. 148 (5). doi:10.1542/peds.2021-054270. PMID 34663682. S2CID 239026000. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Walker 2011, p. 28.

Bibliography

[edit]- Walker, Marsha (2011). Breastfeeding management for the clinician : using the evidence. Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 9780763766511.