Alien (film)

| Alien | |

|---|---|

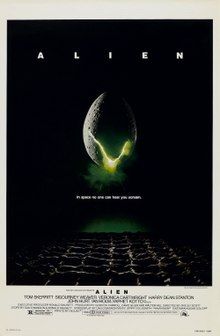

Theatrical release poster by Philip Gips | |

| Directed by | Ridley Scott |

| Screenplay by | Dan O'Bannon |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Derek Vanlint |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[3] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $11 million[a][5] |

| Box office | $187 million[5][6] |

Alien is a 1979 science fiction horror film directed by Ridley Scott and written by Dan O'Bannon, based on a story by O'Bannon and Ronald Shusett. It follows a spaceship crew who investigate a derelict spaceship and are hunted by a deadly extraterrestrial creature. The film stars Tom Skerritt, Sigourney Weaver, Veronica Cartwright, Harry Dean Stanton, John Hurt, Ian Holm, and Yaphet Kotto. It was produced by Gordon Carroll, David Giler, and Walter Hill through their company Brandywine Productions and was distributed by 20th Century-Fox. Giler and Hill revised and made additions to the script; Shusett was the executive producer. The alien creatures and environments were designed by the Swiss artist H. R. Giger, while the concept artists Ron Cobb and Chris Foss designed the other sets.

Alien premiered on May 25, 1979, the opening night of the fourth Seattle International Film Festival.[7][8][9] It received a wide release on June 22 and was released on September 6 in the United Kingdom. It initially received mixed reviews, but won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, three Saturn Awards (Best Science Fiction Film, Best Direction for Scott, and Best Supporting Actress for Cartwright), and a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation. Alien grossed $78.9 million in the United States and £7.8 million in the United Kingdom during its first theatrical run. Its worldwide gross to date has been estimated at between $104 million and $203 million.

In subsequent years, Alien was critically reassessed and is now considered one of the greatest and most influential science fiction and horror films of all time. In 2002, Alien was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. In 2008, it was ranked by the American Film Institute as the seventh-best film in the science fiction genre, and as the 33rd-greatest film of all time by Empire. The success of Alien spawned a media franchise of films, books, video games, and toys, and propelled Weaver's acting career. The story of her character's encounters with the alien creatures became the thematic and narrative core of the sequels Aliens (1986), Alien 3 (1992), and Alien Resurrection (1997). A crossover with the Predator franchise produced the Alien vs. Predator films, while a two-film prequel series was directed by Scott before Alien: Romulus (2024), a standalone sequel, was released.

Plot

[edit]The commercial space tug Nostromo is returning to Earth with a seven-member crew in "stasis" (suspended animation): captain Dallas, executive officer Kane, warrant officer Ripley, navigator Lambert, science officer Ash, and engineers Parker and Brett. The ship's computer, Mother, detects a transmission from a nearby planet and awakens the crew. Following company policy to investigate transmissions indicating intelligent life, they land on the planet and Dallas, Kane, and Lambert head out to investigate. They discover that the transmission comes from a derelict alien spaceship, where they find the remains of a large alien with a hole in its torso. Later, Mother deciphers part of the transmission, which Ripley determines to be a warning message.

Kane discovers a chamber containing hundreds of large eggs. When he touches one, a spider-like creature springs out, penetrates his helmet, and attaches itself to his face. Dallas and Lambert carry the unconscious Kane back to the Nostromo. As the acting senior officer, Ripley refuses to let them aboard, citing quarantine regulations, but Ash overrides her. While Parker and Brett work on repairing the Nostromo, Ash attempts to remove the creature from Kane's face. He stops when he discovers that its highly corrosive acidic blood could harm Kane and potentially damage the ship's hull. The creature eventually detaches itself and dies. After the crew returns to space, Kane awakens with some memory loss but otherwise seems well. During a final crew meal before returning to stasis, he suddenly chokes and convulses. A small alien creature bursts from his chest, killing him, and escapes into the ship.

After ejecting Kane's body out of an airlock, the crew attempts to locate the creature using tracking devices and kill it. Brett follows the crew's pet cat, Jones, into a landing leg compartment,[10] where the now fully grown alien kills Brett. The crew determines that the alien must be in the air ducts. Dallas enters the ducts with a flamethrower, intending to force the creature into an airlock, but it attacks and kills him. Parker later finds only the flamethrower. Lambert suggests fleeing in the escape shuttle, but Ripley, now in command, explains that it will not support four people and insists on continuing Dallas's plan to flush out the alien.

While accessing Mother, Ripley discovers that the crew was awoken and directed to the planet because the company secretly ordered Ash to return with the alien for study, and to consider the crew expendable. She confronts Ash, who tries to kill her. Parker intervenes, knocking Ash's head loose and revealing him to be an android. The survivors reactivate Ash's head, and he confirms the company's orders. Ash states that the alien is unkillable and expresses his admiration for it, taunting them about their chances of survival. Ripley shuts him down and Parker incinerates him.

The crew decides to self-destruct the Nostromo and escape in the shuttle. While gathering supplies, Parker and Lambert are killed by the alien. Now alone, Ripley initiates the self-destruct sequence, but the alien blocks her path to the shuttle. She retreats and unsuccessfully attempts to abort the self-destruct. She reaches the shuttle unhindered with Jones, narrowly escaping as the Nostromo explodes.

As Ripley prepares for stasis, she discovers the alien has stowed itself in a narrow compartment. She dons a spacesuit and flushes it out. It approaches Ripley, but before it can kill her, she opens the airlock door. The resulting explosive decompression almost ejects the alien into space, but it hangs onto the door frame. Ripley fires a grappling hook gun to push it out and activates the engines, blasting the alien into space. After recording her final log entry, she places Jones and herself into stasis for the trip back to Earth.

Cast

[edit]

- Tom Skerritt as Dallas, captain of the Nostromo. Skerritt had been approached early in the film's development, but declined as it did not yet have a director and had a very low budget. Later, when Scott was attached as director and the budget had been doubled, Skerritt accepted the role.[11][12]

- Sigourney Weaver as Ripley, the warrant officer aboard the Nostromo. Meryl Streep was considered for the role, but she was not contacted as her partner John Cazale had recently died.[13] Helen Mirren also auditioned.[14] Weaver, who had Broadway experience but was relatively unknown in film, impressed Scott, Giler, and Hill with her audition. She was the last actor to be cast for the film and performed most of her screen tests in-studio as the sets were being built.[12][15] The role of Ripley was Weaver's first leading role in a motion picture and earned her nominations for a Saturn Award for Best Actress and a BAFTA award for Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Role.[16]

- Veronica Cartwright as Lambert, the Nostromo's navigator. Cartwright had experience in horror and science-fiction films, having acted as a child in The Birds (1963), and more recently in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978).[17] She originally read for the role of Ripley and was not informed that she had instead been cast as Lambert until she arrived in London for wardrobe.[12][18] She disliked the character's emotional weakness,[15] but nevertheless accepted the role: "They convinced me that I was the audience's fears; I was a reflection of what the audience is feeling."[12] Cartwright won a Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance.[19]

- Harry Dean Stanton as Brett, the engineering technician. Stanton's first words to Scott during his audition were, "I don't like sci fi or monster movies".[11] Scott was amused, and convinced Stanton to take the role after reassuring him that Alien would actually be a thriller more akin to Ten Little Indians.[11]

- John Hurt as Kane, the executive officer who becomes the host for the alien. Hurt was Scott's first choice for the role, but he was contracted on a film in South Africa during Alien's filming dates, so Jon Finch was cast as Kane, instead.[15] However, Finch became ill during the first day of shooting and was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, which had also exacerbated a case of bronchitis.[20] Hurt was in London by this time, his South African project having fallen through, and he quickly replaced Finch.[12][20] His performance earned him a nomination for a BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role.[21]

- Ian Holm as Ash, the ship's science officer who is revealed to be an android. Holm was a character actor, who, by 1979, had already been in 20 films.[22]

- Yaphet Kotto as Parker, the chief engineer.[12] Kotto was sent a script off the back of his recent success as villain Dr. Kananga in the James Bond film Live and Let Die (1973), and said he rejected a lucrative film offer in the hope of being cast in Alien.[23]

- Bolaji Badejo as the alien. Badejo, as a 26-year-old design student, was discovered in a bar by a member of the casting team, who put him in touch with Scott.[15][24] Scott believed that Badejo, at 6 feet 10 inches (208 cm) — 7 feet (210 cm) inside the costume — and with a slender frame,[25] could portray the alien and look as if his arms and legs were too long to be real, creating the illusion that a human being could not possibly be inside the costume.[15][24][26] Stuntmen Eddie Powell and Roy Scammell also portrayed the alien in some scenes.[26][27]

- Helen Horton as the voice of Mother, the Nostromo's computer.[28]

Production

[edit]Writing

[edit]

While studying cinema at the University of Southern California, Dan O'Bannon had made a science-fiction comedy film, Dark Star, with director John Carpenter and concept artist Ron Cobb, with production beginning in late 1970.[29] The film featured an alien (created by spray-painting a beach ball and adding rubber "claws"), which was played for the comedic effect. The experience left O'Bannon "really wanting to do an alien that looked real."[29][30] A "couple of years" later he began work on a similar story that would focus more on horror. "I knew I wanted to do a scary movie on a spaceship with a small number of astronauts", he later recalled, "Dark Star as a horror movie instead of a comedy."[29] Ronald Shusett, meanwhile, was working on an early version of what would eventually become Total Recall.[29][30] Impressed by Dark Star, he contacted O'Bannon and the two agreed to collaborate on their projects, choosing to work on O'Bannon's film first, as they believed it would be less costly to produce.[29][30]

O'Bannon had written 29 pages of a script titled Memory, containing what would become the opening scenes of Alien: a crew of astronauts awakens to find that their voyage has been interrupted because they are receiving a signal from a mysterious planetoid. They investigate and their ship breaks down on the surface.[26][30] He did not yet have a clear idea as to what the alien antagonist of the story would be.[29]

O'Bannon soon accepted an offer to work on Alejandro Jodorowsky's adaptation of Dune, a project that took him to Paris for six months.[29][31] Though the project ultimately fell through, it introduced him to several artists whose work gave him ideas for his science-fiction story including Chris Foss, H. R. Giger, and Jean "Moebius" Giraud.[26] O'Bannon was impressed by Foss's covers for science-fiction books, while he found Giger's work "disturbing":[29] "His paintings had a profound effect on me. I had never seen anything that was quite as horrible and at the same time as beautiful as his work. And so I ended up writing a script about a Giger monster."[26] After the Dune project collapsed, O'Bannon found himself homeless and broke, and returned to Los Angeles where he would borrow Shusett's couch. In need of money he decided to write a spec script the studios would buy,[32] and the two revived his Memory script. Shusett suggested that O'Bannon use one of his other film ideas, about gremlins infiltrating a B-17 bomber during World War II, and set it on the spaceship as the second half of the story.[26][31] The working title of the project was now Star Beast, but O'Bannon disliked this and changed it to Alien after noting the number of times that the word appeared in the script. O'Bannon and Shusett liked the new title's simplicity and its double meaning as both a noun and an adjective.[26][29][33] Shusett came up with the idea that one of the crew members could be implanted with an alien embryo that would burst out of him; he thought this would be an interesting plot device by which the alien could board the ship.[29][31]

Dan [O'Bannon] put his finger on the problem: what has to happen next is the creature has to get on the ship in an interesting way. I have no idea how, but if we could solve that, if it can't be that it just snuck in, then I think the whole movie will come into place. In the middle of the night, I woke up and I said, "Dan I think I have an idea: the alien screws one of them [...] it jumps on his face and plants its seed!" And Dan says, oh my god, we've got it, we've got the whole movie.

O'Bannon drew inspiration from many works of science fiction and horror. He later said: "I didn't steal Alien from anybody. I stole it from everybody!"[36] The Thing from Another World (1951) inspired the idea of professional men being pursued by a deadly alien creature through a claustrophobic environment.[36] Forbidden Planet (1956) gave O'Bannon the idea of a ship being warned not to land, and then the crew being killed one by one by a mysterious creature when they defy the warning.[36] Planet of the Vampires (1965) contains a scene in which the heroes discover a giant alien skeleton; this influenced the Nostromo crew's discovery of the alien creature in the derelict spacecraft.[36] O'Bannon has also noted the influence of "Junkyard" (1953), a short story by Clifford D. Simak in which a crew lands on an asteroid and discovers a chamber full of eggs.[30] He has also cited as influences Strange Relations by Philip José Farmer (1960), which covers alien reproduction and various EC Comics horror titles carrying stories in which monsters eat their way out of people.[30]

With most of the plot in place, Shusett and O'Bannon presented their script to several studios,[29] pitching it as "Jaws in space".[37] They were on the verge of signing a deal with Roger Corman's studio when a friend offered to find them a better deal and passed the script on to Gordon Carroll, David Giler, and Walter Hill, who had formed a production company called Brandywine with ties to 20th Century-Fox.[29][38] O'Bannon and Shusett signed a deal with Brandywine, but Hill and Giler were not satisfied with the script and made numerous rewrites and revisions.[29][39] This caused tension with O'Bannon and Shusett, since Hill and Giler had very little experience with science fiction; according to Shusett, "They weren't good at making it better, or, in fact, at not making it even worse."[29] O'Bannon believed that Hill and Giler were attempting to justify taking his name off the script and claiming Shusett's and his work as their own.[29] Hill and Giler did add some substantial elements to the story, including the android character Ash, which O'Bannon felt was an unnecessary subplot[22] but which Shusett later described as "one of the best things in the movie...That whole idea and scenario was theirs."[29] Hill and Giler went through eight drafts of the script in total, concentrating largely on the Ash subplot, but also making the dialogue more natural and trimming some sequences set on the alien planetoid.[40] Despite the fact that the final shooting script was written by Hill and Giler, the Writers Guild of America awarded O'Bannon sole credit for the screenplay.[41]

Development

[edit]

20th Century-Fox did not express confidence in financing a science-fiction film. However, after the success of Star Wars in 1977, its interest in the genre rose substantially. According to Carroll: "When Star Wars came out and was the extraordinary hit that it was, suddenly science fiction became the hot genre." O'Bannon recalled that "They wanted to follow through on Star Wars, and they wanted to follow through fast, and the only spaceship script they had sitting on their desk was Alien".[29] Alien was greenlit by 20th Century-Fox, with an initial budget of $4.2 million.[29][40] It was funded by North Americans, but made by 20th Century-Fox's British production subsidiary.[42]

O'Bannon had originally assumed that he would direct Alien, but 20th Century-Fox instead asked Hill to direct.[40][43] Hill declined due to other film commitments, as well as not being comfortable with the level of visual effects that would be required.[44] Peter Yates, John Boorman,[45] Jack Clayton, Robert Aldrich, and Robert Altman were considered for the task, but O'Bannon, Shusett, and the Brandywine team felt that these directors would not take the film seriously and would instead treat it as a B monster movie.[43][46][47] According to Cobb, Steven Spielberg was also considered to direct the film and was interested but prior obligations prevented him from directing the film.[48] Giler, Hill, and Carroll had been impressed by Ridley Scott's debut feature film The Duellists (1977) and made an offer to him to direct Alien, which Scott quickly accepted.[26][46] Scott created detailed storyboards for the film in London, which impressed Fox enough to double the film's budget.[11][43] His storyboards included designs for the spaceship and space suits, drawing on such films as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars.[11][49] However, he was keen on emphasizing horror in Alien rather than fantasy, describing the film as "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre of science fiction".[43][46]

Casting

[edit]Casting calls and auditions were held in New York City and London.[11] With only seven human characters in the story, Scott sought to hire strong actors so he could focus most of his energy on the film's visual style.[11] He employed casting director Mary Selway, who had worked with him on The Duellists, to head the casting in the United Kingdom, while Mary Goldberg handled casting in the United States.[12][50] In developing the story, O'Bannon had focused on writing the alien first, putting off developing the other characters.[43] Shusett and he had intentionally written all the roles generically; they made a note in the script that explicitly states, "The crew is unisex and all parts are interchangeable for men or women."[12][51] This freed Scott, Selway, and Goldberg to interpret the characters as they pleased, and to cast accordingly. They wanted the Nostromo's crew to resemble working astronauts in a realistic environment, a concept summarized as "truckers in space".[11][12] According to Scott, this concept was inspired partly by Star Wars, which deviated from the pristine future often depicted in science-fiction films of the time.[52]

To assist the actors in preparing for their roles, Scott wrote several pages of backstory for each character explaining their histories.[40][53] He filmed many of their rehearsals to capture spontaneity and improvisation, and tensions between some of the cast members, particularly towards the less-experienced Weaver; this translated convincingly to film as tension between the characters.[53] Roger Ebert notes that the actors in Alien were older than was typical in thriller films at the time, which helped make the characters more convincing:

None of them were particularly young. Tom Skerritt, the captain, was 46, Hurt was 39 but looked older, Holm was 48, Harry Dean Stanton was 53, Yaphet Kotto was 42, and only Veronica Cartwright at 30 and Weaver at 28 were in the age range of the usual thriller cast. Many recent action pictures have improbably young actors cast as key roles or sidekicks, but by skewing older, Alien achieves a certain texture without even making a point of it: These are not adventurers but workers, hired by a company to return 20 million tons of ore to Earth.[54]

David McIntee, author of Beautiful Monsters: The Unofficial and Unauthorized Guide to the Alien and Predator Films, asserts that part of the film's effectiveness in frightening viewers "comes from the fact that the audience can all identify with the characters...Everyone aboard the Nostromo is a normal, everyday, working Joe just like the rest of us. They just happen to live and work in the future."[55]

Filming

[edit]

Alien was filmed over 14 weeks from July 5 to October 21, 1978.[56] Principal photography took place at Pinewood Studios and Shepperton Studios near London, while model and miniature filming was done at Bray Studios in Water Oakley, Berkshire.[50] The production schedule was short due to the film's low budget and pressure from 20th Century-Fox to finish on time.[53]

A crew of over 200 craftspeople and technicians constructed the three principal sets: the surface of the alien planetoid, and the interiors of the Nostromo and the derelict spacecraft.[26] Art director Les Dilley created 1⁄24-scale miniatures of the planetoid's surface and derelict spacecraft based on Giger's designs, then made moulds and casts and scaled them up as diagrams for the wood and fiberglass forms of the sets.[11] Tons of sand, plaster, fiberglass, rock, and gravel were shipped into the studio to sculpt a desert landscape for the planetoid's surface, which the actors would walk across wearing space-suit costumes.[26] The suits were thick, bulky, and lined with nylon, had no cooling systems, and initially, no venting for their exhaled carbon dioxide to escape.[57] Combined with a heat wave, these conditions nearly caused the actors to pass out; nurses had to be kept on-hand with oxygen tanks.[53][57]

All of the visuals on the computer screens on the Nostromo's bridge are computer-generated imagery (CGI). The staff used CGI because it was easier than any alternative.[58]

For scenes showing the exterior of the Nostromo, a 58-foot (18 m) landing leg was constructed to give a sense of the ship's size. Scott was not convinced that it looked large enough, so he had his two young sons and the son of Derek Vanlint (the film's cinematographer) stand in for the regular actors, wearing smaller space suits to make the set pieces seem larger.[57][59] The same technique was used for the scene in which the crew members encounter the dead alien creature in the derelict spacecraft. The children nearly collapsed due to the heat of the suits; oxygen systems were eventually added to help the actors breathe.[53][57] Four identical cats were used to portray Jones, the crew's pet.[50] During filming, Weaver discovered that she was allergic to the combination of cat hair and the glycerin placed on the actors' skin to make them appear sweaty. By removing the glycerin she was able to continue working with the cats.[20][53]

Alien originally was to conclude with the destruction of the Nostromo while Ripley escapes in the shuttle Narcissus. However, Scott conceived of a "fourth act" in which Ripley is forced to confront the alien on the shuttle. He pitched the idea to 20th Century-Fox and negotiated an increase in the budget to film it over several extra days.[22][60] Scott had wanted the alien to bite off Ripley's head and make the final log entry in her voice, but the producers vetoed this idea, because they believed the alien should die at the end of the film.[60]

Post-production

[edit]Editing and post-production took roughly 20 weeks and concluded in late January 1979.[61] The editor, Terry Rawlings, had previously worked with Scott on editing sound for The Duellists.[61] Scott and Rawlings edited much of Alien to have a slow pace to build suspense for the more tense and frightening moments. According to Rawlings: "I think the way we did get it right was by keeping it slow, funny enough, which is completely different from what they do today. And I think the slowness of it made the moments that you wanted people to be sort of scared...then we could go as fast as we liked because you've sucked people into a corner and then attacked them, so to speak. And I think that's how it worked."[61] The first cut of the film was over three hours long; the final version is just under two hours.[61][62]

One scene that was cut from the film occurred during Ripley's final escape from the Nostromo; she encounters Dallas and Brett, who have been partially cocooned by the alien. O'Bannon had intended the scene to indicate that Brett was becoming an alien egg, while Dallas was held nearby to be implanted by the resulting facehugger.[38] Production designer Michael Seymour later suggested that Dallas had "become sort of food for the alien creature",[59] while Ivor Powell suggested that "Dallas is found in the ship as an egg, still alive."[61] Scott remarked, "they're morphing, metamorphosing, they are changing into...being consumed, I guess, by whatever the alien's organism is...into an egg."[22] The scene was cut partly because it did not look realistic enough, but also because it slowed the pace of the escape sequence.[38][60] Tom Skerritt remarked that "The picture had to have that pace. Her trying to get the hell out of there, we're all rooting for her to get out of there, and for her to slow up and have a conversation with Dallas was not appropriate."[61] The footage was included with other deleted scenes as a special feature on the Laserdisc release of Alien, and a shortened version of it was reinserted into the 2003 Director's Cut, which was re-released in theaters and on DVD.[38][63]

Music

[edit]

The musical score was composed by Jerry Goldsmith, conducted by Lionel Newman, and performed by the National Philharmonic Orchestra. Scott had originally wanted the film to be scored by Isao Tomita, but Fox wanted a more familiar composer and Goldsmith was recommended by then-president of Fox Alan Ladd Jr.[64] Goldsmith wanted to create a sense of romanticism and lyrical mystery in the film's opening scenes, which would build throughout the film to suspense and fear.[61] Scott did not like Goldsmith's original main title piece, however, so Goldsmith rewrote it as "the obvious thing: weird and strange, and which everybody loved."[61][64] Another source of tension was editor Terry Rawlings' choice to use pieces of Goldsmith's music from previous films, including a piece from Freud: The Secret Passion, and to use an excerpt from Howard Hanson's Symphony No. 2 ("Romantic") for the end credits.[61][64][65][66]

Scott and Rawlings had also become attached to several of the musical cues they had used for the temporary score while editing the film, and re-edited some of Goldsmith's cues and rescored several sequences to match these cues and even left the temporary score in place in some parts of the finished film.[61] Goldsmith later said, "You can see that I was sort of like going at opposite ends of the pole with the filmmakers."[61] Nevertheless, Scott praised Goldsmith's score as "full of dark beauty"[64] and "seriously threatening, but beautiful".[61] It was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score, a Grammy Award for Best Soundtrack Album, and it won a BAFTA Award for Best Film Music.[67][68][69] The score has been released as a soundtrack album in several versions with different tracks and sequences.[70]

Design

[edit]Creature effects

[edit]O'Bannon introduced Scott to the artwork of H. R. Giger; both of them felt that his painting Necronom IV was the type of representation they wanted for the film's antagonist and began asking the studio to hire him as a designer.[43][46] Fox initially believed Giger's work was too ghastly for audiences, but the Brandywine team were persistent and eventually won out.[46] According to Gordon Carroll: "The first second that Ridley saw Giger's work, he knew that the biggest single design problem, maybe the biggest problem in the film, had been solved."[43] Scott flew to Zürich to meet Giger and recruited him to work on all aspects of the alien and its environment including the surface of the planetoid, the derelict spacecraft, and all four forms of the alien from the egg to the adult.[43][46]

The scene of Kane inspecting the egg was shot in postproduction. A fiberglass egg was used so that actor John Hurt could shine his light on it and see movement inside, which was provided by Scott fluttering his hands inside the egg while wearing rubber gloves.[72] The top of the egg was hydraulic, and the innards were a cow's stomach and tripe.[24][72] Test shots of the eggs were filmed using hen's eggs, and this footage was used in early teaser trailers. For this reason, the image of a hen's egg was used on the poster and has become emblematic of the franchise as a whole—as opposed to the alien egg that appears in the finished film.[72]

The "facehugger" and its proboscis, which was made of a sheep's intestine, were shot out of the egg using high-pressure air hoses. The shot was reversed and slowed down in editing to prolong the effect and reveal more detail.[24][72] The facehugger itself was the first creature that H.R. Giger designed for the film, going through several versions in different sizes before deciding on a small creature with human-like fingers and a long tail.[24][71] Dan O'Bannon, with help from Ron Cobb, drew his own version based on Giger's design, which became the final version.[22][71] Cobb came up with the idea that the creature could have a powerful acid for blood, a characteristic that would carry over to the adult Alien and would make it impossible for the crew to kill it by conventional means, such as guns or explosives, since the acid would burn through the ship's hull.[22][31] For the scene in which the dead facehugger is examined, Scott used pieces of fish and shellfish to create its viscera.[24][72]

The "chestburster" design was inspired by Francis Bacon's 1944 painting Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.[24] Giger's original design, which was refined, resembled a plucked chicken.[24] Screenwriter Dan O'Bannon credits his experiences with Crohn's disease for inspiring the chest-bursting scene.[73]

For the filming of the chestburster scene, the cast members knew that the creature would be bursting out of Hurt, and had seen the chestburster puppet, but they had not been told that fake blood would also be bursting out in every direction from high-pressure pumps and squibs.[20][74] The scene was shot in one take using an artificial torso filled with blood and viscera, with Hurt's head and arms coming up from underneath the table. The chestburster was shoved up through the torso by a puppeteer who held it on a stick. When the creature burst through the chest, a stream of blood shot directly at Cartwright, shocking her enough that she fell over and went into hysterics.[20][24][26] According to Tom Skerritt, "What you saw on camera was the real response. She had no idea what the hell happened. All of a sudden this thing just came up."[24] The creature then runs off-camera, an effect accomplished by cutting a slit in the table for the puppeteer's stick to go through and passing an air hose through the puppet's tail to make it whip about.[24]

The real-life surprise of the actors gave the scene an intense sense of realism and made it one of the film's most memorable moments. During preview screenings, the crew noticed that some viewers would move towards the back of the theater so as not to be too close to the screen during the sequence.[62] The scene has frequently been called one of the most memorable moments in cinema history.[75] In 2007, Empire named it as the greatest 18-rated moment in film, ranking it above the decapitation scene in The Omen (1976) and the transformation sequence in An American Werewolf in London (1981).[76] IGN ranked it the 10th-best film moment of all time.[77]

For the scene in which Ash is revealed to be an android, a puppet was created of his torso and upper body, which was operated from underneath.[53] During a preview screening, this scene caused an usher to faint.[62][78] In the following scene, Ash's head is placed on a table and reactivated; for portions of this scene, an animatronic head was made using a face cast of Holm.[60] However, the latex of the head shrank while curing and the result was not entirely convincing.[53] For the bulk of the scene, Holm knelt under the table with his head through a hole. Milk, caviar, pasta, fiber optics, and Foley urinary catheters were combined to form the android innards.[53][60]

The alien

[edit]Giger made several conceptual paintings of the adult alien before settling on the final version. He sculpted the body using plasticine, incorporating pieces such as vertebrae from snakes and cooling tubes from a Rolls-Royce.[15][24] The head was manufactured separately by Carlo Rambaldi, who had worked on the aliens in Close Encounters of the Third Kind.[79] Rambaldi followed Giger's designs closely, making some modifications to incorporate the moving parts that would animate the jaw and inner mouth.[24] A system of hinges and cables was used to operate the rigid tongue, which protruded from the mouth and featured a second mouth at its tip with its own set of movable teeth.[24] The final head had about 900 moving parts and points of articulation.[24] Part of a human skull was used as the "face", and was hidden under the smooth, translucent cover of the head.[15] Rambaldi's original alien jaw is now on display in the Smithsonian Institution.[60] In April 2007, the original alien suit was sold at auction.[80] Copious amounts of K-Y Jelly were used to simulate saliva and give the alien a slimy appearance.[24][71] The alien vocalizations were provided by Percy Edwards, a voice artist who had provided bird sounds for British television throughout the 1960s and 1970s and the whale sounds for Orca: Killer Whale (1977).[64][81]

In most scenes, the alien was portrayed by Bolaji Badejo. A latex costume was made to fit Badejo's slender 6-foot-10-inch (208 cm) frame by taking a full-body plaster cast.[24][26] Scott later said that the alien "takes on elements of the host – in this case, a man".[46] Badejo attended tai chi and mime classes to create convincing movements.[15][24] For some scenes, such as when the alien lowers itself from the ceiling to kill Brett, it was portrayed by stuntmen Eddie Powell and Roy Scammell.[26][27] Powell, in costume, was suspended on wires and then lowered in an unfurling motion.[24][72]

Scott chose not to show the full alien for most of the film, keeping most of its body in shadow to create a sense of terror and heighten suspense. The audience could thus project their own fears into imagining what the rest of the creature might look like:[24] "Every movement is going to be very slow, very graceful, and the alien will alter shape so you never really know exactly what he looks like."[26] Scott said: "I've never liked horror films before, because in the end it's always been a man in a rubber suit. Well, there's one way to deal with that. The most important thing in a film of this type is not what you see, but the effect of what you think you saw."[26]

The alien has been referred to as "one of the most iconic movie monsters", and its biomechanical appearance and sexual overtones have been frequently noted.[82] Roger Ebert wrote that "Alien uses a tricky device to keep the alien fresh throughout the movie: it evolves the nature and appearance of the creature, so we never know quite what it looks like or what it can do... The first time we get a good look at the alien, as it bursts from the chest of poor Kane (John Hurt). It is unmistakably phallic in shape, and the critic Tim Dirks mentions its 'open, dripping vaginal mouth'."[54]

Sets

[edit]The sets of the Nostromo's three decks were each created almost entirely in one piece, with each deck occupying a separate stage. The actors had to navigate through the hallways that connected the stages, adding to the sense of claustrophobia and realism.[26][53][71] The sets used large transistors and low-resolution computer screens to give the ship a "used", industrial look and make it appear as though it was constructed of "retrofitted old technology".[59] Ron Cobb created industrial-style symbols and color-coded signs for various areas and aspects.[59] The company that owns the Nostromo is not named in the film, and is referred to by the characters as "the company". However, the name and logo of the company appears on several set pieces and props such as computer monitors and beer cans as "Weylan-Yutani".[83] Cobb created the name to imply a business alliance between Britain and Japan, deriving "Weylan" from the British Leyland Motor Corporation and "Yutani" from the name of his Japanese neighbor.[84][85] The 1986 sequel, Aliens, named the company "Weyland-Yutani",[84][86] and it has remained a central aspect of the franchise.

Art director Roger Christian used scrap metal and parts to create set pieces and props to save money, a technique he employed while working on Star Wars.[59][87] For example, some of the Nostromo's corridors were created from portions of scrapped bomber aircraft, and a mirror was used to create the illusion of longer corridors in the below-deck area.[59] Special-effects supervisors Brian Johnson and Nick Allder made many of the set pieces and props function, including moving chairs, computer monitors, motion trackers and flamethrowers.[20][26]

Giger designed and worked on all the alien aspects, which he designed to appear organic and biomechanical in contrast to the industrial look of the Nostromo and its human elements.[26][59] For the interior of the derelict spacecraft and egg chamber, he used dried bones with plaster to sculpt the scenery and elements.[26][59] Veronica Cartwright described Giger's sets as "so erotic...it's big vaginas and penises...the whole thing is like you're going inside of some sort of womb or whatever...it's sort of visceral."[59] The set with the deceased alien creature, which the production team nicknamed the "space jockey", proved problematic, as 20th Century-Fox did not want to spend the money for such an expensive set that would only be used for one scene. Scott described the set as the cockpit or driving deck of the mysterious ship, and the production team convinced the studio that the scene was important to impress the audience and make them aware that this was not a B movie.[59][72] To save money, only one wall of the set was created, and the "space jockey" sat atop a disc that could be rotated to facilitate shots from different angles in relation to the actors.[26][72] Giger airbrushed the entire set and the "space jockey" by hand.[59][72]

The origin of the jockey creature is not explored, but Scott later theorized that it might have been the ship's pilot, and that the ship might have been a weapons-carrier capable of dropping alien eggs onto a planet so that the aliens could use the local lifeforms as hosts.[22] In early versions of the script, the eggs were to be located in a separate pyramid structure, which would be found later by the Nostromo crew and would contain statues and hieroglyphs depicting the alien reproductive cycle, contrasting the human, alien, and space-jockey cultures.[31] Cobb, Foss, and Giger each created concept artwork for these sequences, but they were discarded due to budgetary concerns and the need to shorten the film.[26] Instead, the egg chamber was set inside the derelict ship and was filmed on the same set as the space-jockey scene; the entire disc piece supporting the jockey and its chair was removed and the set was redressed to create the egg chamber.[26] Light effects in the egg chamber were created by lasers borrowed from English rock band the Who. The band was testing the lasers for use in their stage show on the sound stage next door.[88]

Spaceships and planets

[edit]I resent films that are so shallow they rely entirely on their visual effects, and of course science-fiction films are notorious for this. I've always felt that there's another way to do it: a lot of effort should be expended toward rendering the environment of the spaceship, or space travel, whatever the fantastic setting of your story should be–as convincingly as possible, but always in the background. That way the story and the characters emerge and they become more real.

O'Bannon brought in artists Ron Cobb and Chris Foss, with whom he had worked on Dark Star and Dune respectively, to work on designs for the human aspects such as the spaceship and space suits.[43][84] Cobb created hundreds of preliminary sketches of the interiors and exteriors of the ship, which went through many design concepts and possible names such as Leviathan and Snark as the script developed. The final name was derived from the title of Joseph Conrad's 1904 novel Nostromo, while the escape shuttle, called Narcissus in the script, was named after Conrad's 1897 novella The Nigger of the 'Narcissus'.[83] The production team particularly praised Cobb's ability to depict the interior settings of the ship in a realistic and believable manner. Under Scott's direction, the design of the Nostromo shifted towards an 800-foot-long (240 m) tug towing a refining platform 2 miles (3.2 km) long and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) wide.[26] Cobb also created some conceptual drawings of the alien, which went unused.[43][84] Moebius was attached to the project for a few days and his costume renderings were the basis for the final space suits created by costume designer John Mollo.[26][84]

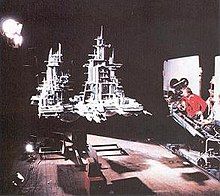

The spaceships and planets were shot using models and miniatures. These included models of the Nostromo, its attached mineral refinery, the escape shuttle Narcissus, the alien planetoid, and the exterior and interior of the derelict spacecraft. Visual-effects supervisor Brian Johnson and supervising modelmaker Martin Bower and their team worked at Bray Studios, roughly 25 miles (40 km) from Shepperton Studios.[89][90] The designs of the Nostromo and its attachments were based on combinations of Scott's storyboards and Ron Cobb's conceptual drawings.[89] The basic outlines of the models were made of wood and plastic, and most of the fine details were added from model kits of warships, tanks, and World War II bombers.[citation needed]

Three models of the Nostromo were made: a 12-inch (30 cm) version for medium and long shots, a 4-foot (1.2 m) version for rear shots, and a 12-foot (3.7 m), 7-short-ton (6.4 t) rig for the undocking and planetoid surface sequences.[26][90] Scott insisted on numerous changes to the models even as filming was taking place, leading to conflicts with the modeling and filming teams. The Nostromo was originally yellow, and the team filmed shots of the models for six weeks before Johnson left to work on The Empire Strikes Back. Scott then ordered it changed to gray, and the team had to begin shooting again from scratch.[89][90] He asked that more and more pieces be added to the model such that the final version (with the refinery) required a metal framework so that it could be hoisted by a forklift. He also took a hammer and chisel to sections of the refinery, knocking off many of the spires that Bower had spent weeks creating. Scott also had disagreements with miniature-effects cinematographer Dennis Ayling over how to light the models.[89]

A separate model, about 40 feet (12 m) long, was created for the Nostromo's underside from which the Narcissus would detach and from which Kane's body would be launched during the funeral scene. Bower carved Kane's burial shroud out of wood; it was launched through the hatch using a small catapult and filmed at high speed. The footage was slowed down in editing.[89][79] Only one shot was filmed using blue-screen compositing – that of the shuttle racing past the Nostromo. The other shots were simply filmed against black backdrops, with stars added by double exposure.[90] Though motion control photography technology was available at the time, the budget would not allow for it. Instead, the team used a camera with wide-angle lenses mounted on a drive mechanism to make slow passes over and around the models filming at 2+1⁄2 frames per second,[26] giving them the appearance of motion. Scott added smoke and wind effects to enhance the illusion.[89] For the scene in which the Nostromo detaches from the refinery, a 30-foot (9.1 m) docking arm was created using pieces from model railway kits. The Nostromo was pushed away from the refinery by a forklift covered in black velvet, causing the arm to extend out from the refinery. This created the illusion that the arm was pushing the ship forward.[89][90] Shots of the ship's exterior in which characters are seen moving around inside were filmed using larger models, which contained projection screens displaying pre-recorded footage.[89]

A separate model was created for the exterior of the derelict alien spacecraft. Matte paintings were used to fill in areas of the ship's interior, as well as exterior shots of the planetoid's surface.[89] The surface as seen from space during the landing sequence was created by painting a globe white, then mixing chemicals and dyes onto transparencies and projecting them onto it.[26][90] The planetoid was not named in the film, but some drafts of the script gave it the name Acheron[15] after the river which in Greek mythology is described as the "stream of woe"; it is a branch of the river Styx, and forms the border of Hell in Dante's Inferno. The 1986 sequel Aliens named the planetoid as "LV-426",[86] and both names have been used for it in subsequent expanded-universe media such as comic books and video games.

Title sequence

[edit]The title sequence was developed by R/Greenberg Associates "to instill a sense of foreboding, the letters broken into pieces, the space between them unsettling."[91] It is referenced as one of the most iconic opening sequences of all time.[92]

Release

[edit]"It was the most incredible preview I've ever been in. I mean, people were screaming and running out of the theater."[78]

An initial screening of Alien for 20th Century-Fox representatives in St. Louis was marred by poor sound. A subsequent screening in a newer theater in Dallas went significantly better, eliciting genuine fright from the audience.[78] Two theatrical trailers were shown to the public. The first consisted of rapidly changing still images set to some of Jerry Goldsmith's electronic music from Logan's Run, with the tagline in both the trailer and on the teaser poster "A word of warning...". The second used test footage of a hen's egg set to part of Goldsmith's Alien score.[62] The film was previewed in various American cities in the spring of 1979[62] and was promoted with the tagline "In space, no one can hear you scream."[78][93]

Alien was rated "R" in the United States, "X" in the United Kingdom, and "M" in Australia.[50] In the UK, the British Board of Film Censors almost passed the film as an "AA" (for ages 14 and over), although concerns existed over the prevalent sexual imagery. 20th Century-Fox eventually relented in pushing for an AA certificate after deciding that an X rating would make it easier to sell as a horror film.[94]

Alien opened in a limited release in American theaters on May 25, 1979.[93][95] The film had no formal premiere, yet moviegoers lined up for blocks to see it at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, where a number of models, sets, and props were displayed outside to promote it during its first run.[62][78] It received a wide release in the United States on June 22.[96] Vandals set fire to the model of the space jockey, believing it to be the work of the devil.[62] The film started its international release in Japan on July 20 and then Brazil on August 20.[97] In the United Kingdom, Alien premiered at a gala performance at the Edinburgh Film Festival on September 1, 1979,[98][99] before starting an exclusive run at the Odeon Leicester Square in London on Thursday, September 6, 1979,[100] for one week before expanding slowly until opening wide in Britain in 180 theaters on October 1, 1979.[97] The film opened in France and Spain in September before expanding to other markets in October 1979.[97]

Box office

[edit]The film was a commercial success, opening in 90 theaters across the United States (plus 1 in Canada), setting 51 house records and grossing $3,527,881 over the four-day Memorial Day weekend with a per-screen average of $38,767,[5] which Daily Variety suggested may have been the biggest per-screen opening in history.[101] In its first 4 weeks it grossed $16.5 million from only 148 prints before expanding to 635 screens.[5] In the UK, the film grossed $126,150 in its first 4 days at the Odeon Leicester Square, setting a house record.[102] By the beginning of October 1979, the film had grossed $27 million internationally including $16.9 million in Japan, $4.8 million in France and $3.7 million in the UK.[97] It went on to gross $78.9 million in the United States and £7,886,000 in the United Kingdom during its first run.[62] Including reissues, it has grossed $81.8 million in the United States and Canada, while international box-office figures have varied from $24 million to $122.7 million. Its total worldwide gross has been listed within the range of $104.9 million[5] to $203.6 million.[6] In 1992, Fox noted the worldwide gross was $143 million.[103]

20th Century Fox claimed that Alien lost $2 million in the 11 months following its release. The claim was decried by industry accountants as an example of Hollywood creative accounting, used to disguise the revenue and limit any payments to Brandywine. By August 1980, Fox readjusted the figure to $4 million profit, although this was similarly refuted. Eager to begin work on a sequel, Brandywine sued Fox over their profit distribution tactics, but Fox claimed that Alien was not a financial success and did not warrant a sequel. The lawsuit was settled in 1983 when Fox agreed to fund a sequel.[104]

Critical reception

[edit]Critical reaction to Alien was initially mixed. Some critics who were not usually favorable towards science fiction, such as Barry Norman of the BBC's Film series, were positive about the film's merits.[62] Others, however, were not; reviews by Variety, Sight and Sound, Vincent Canby, and Leonard Maltin[b] were mixed or negative.[106] A review by Time Out said the film was an "empty bag of tricks whose production values and expensive trickery cannot disguise imaginative poverty".[107] In their original review on Sneak Previews, critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert gave the film "two 'yes' votes." Ebert called it "one of the scariest old-fashioned space operas I can remember." Siskel agreed that it was scary but said it was basically a "haunted house film" set "in a spaceship" and was "not the greatest science fiction film ever made."[108] Siskel gave the film three stars out of four in his original print review, calling it "an accomplished piece of scary entertainment" and praising Sigourney Weaver as "an actress who should become a major star," but listed among the film's disappointments that "[f]or me, the final shape of the alien was the least scary of its forms."[109]

Accolades

[edit]Alien won the 1980 Academy Award for Best Visual Effects and was also nominated for Best Art Direction (for Michael Seymour, Leslie Dilley, Roger Christian, and Ian Whittaker).[110][111] It won Saturn Awards for Best Science Fiction Film, Best Direction for Ridley Scott, and Best Supporting Actress for Veronica Cartwright,[19] and was also nominated in the categories of Best Actress for Sigourney Weaver, Best Make-up for Pat Hay, Best Special Effects for Brian Johnson and Nick Allder, and Best Writing for Dan O'Bannon.[112] It was also nominated for British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) awards for Best Costume Design for John Mollo, Best Editing for Terry Rawlings, Best Supporting Actor for John Hurt, and Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Role for Sigourney Weaver.[69] It also won a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and was nominated for a British Society of Cinematographers award for Best Cinematography for Derek Vanlint, as well as a Silver Seashell award for Best Cinematography and Special Effects at the San Sebastián International Film Festival.[113][114] Jerry Goldsmith's score received nominations for the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score, the Grammy Award for Best Soundtrack Album, and won a BAFTA Award for Best Film Music.[67][68][69]

Post-release

[edit]Home video

[edit]Alien has been released in many home video formats and packages over the years. The first of these was a 17-minute Super-8 version for home projectionists.[115] It was also released on both VHS and Betamax for rental, which grossed it an additional $40,300,000 in the United States alone.[62] Several VHS releases were subsequently issued both separately and as boxed sets. LaserDisc and Videodisc versions followed, including deleted scenes and director commentary as bonus features.[115][116] A VHS box set containing Alien and its sequels Aliens and Alien 3 was released in facehugger-shaped boxes, and included some of the deleted scenes from the Laserdisc editions.[116] In addition, all three films were released on THX certified widescreen VHS releases in 1997.[117] When Alien Resurrection premiered in theaters that year, another set of the first three films was released including a Making of Alien Resurrection tape. A few months later, the set was re-released with the full version of Alien Resurrection taking the place of the making-of video.[116] Alien was released on DVD in 1999, both separately and, as The Alien Legacy, packaged with Aliens, Alien 3 and Alien Resurrection.[118] This set, which was also released in a VHS version, included a commentary track by Ridley Scott.[115][116] The first three films of the series have also been packaged as the Alien Triple Pack.

"The traditional definition of the term 'Director's Cut' suggests the restoration of a director's original vision, free of any creative limitations. It suggests that the filmmaker has finally overcome the interference of heavy-handed studio executives, and that the film has been restored to its original, untampered form. Such is not the case with Alien: The Director's Cut. It's a completely different beast."[119]

Director's Cut

[edit]In 2003, 20th Century Fox was preparing the Alien Quadrilogy DVD box set, which would include Alien and its three sequels. In addition, the set would also include alternative versions of all four films in the form of "special editions" and "director's cuts". Fox approached Scott to digitally restore and remaster Alien, and to restore several scenes which had been cut during the editing process for inclusion in an expanded version of the film.[119] Upon viewing the expanded version, Scott felt that it was too long and chose to recut it into a more streamlined alternative version:

Upon viewing the proposed expanded version of the film, I felt that the cut was simply too long and the pacing completely thrown off. After all, I cut those scenes out for a reason back in 1979. However, in the interest of giving the fans a new experience with Alien, I figured there had to be an appropriate middle ground. I chose to go in and recut that proposed long version into a more streamlined and polished alternate version of the film. For marketing purposes, this version is being called "The Director's Cut."[119]

The "Director's Cut" restored roughly four minutes of deleted footage, while cutting about five minutes of other material, leaving it about a minute shorter than the theatrical cut.[62] Many of the changes were minor, such as altered sound effects, trimming of some shots to speed up the film's pace and the removal of the "What Are My Chances?" scene. The restored footage included the scene in which Ripley discovers the cocooned Dallas and Brett during her escape of the Nostromo. Fox released the Director's Cut in theaters on October 31, 2003.[62] The Alien Quadrilogy boxed set was released December 2, 2003, with both versions of the film included along with a new commentary track featuring many of the film's actors, writers, and production staff, as well as other special features and a documentary entitled The Beast Within: The Making of Alien. Each film was also released separately as a DVD with both versions of the film included. Scott noted that he was very pleased with the original theatrical cut of Alien, saying that "For all intents and purposes, I felt that the original cut of Alien was perfect. I still feel that way", and that the original 1979 theatrical version "remains my version of choice".[119] He has since stated that he considers both versions "director's cuts", as he feels that the 1979 version was the best he could possibly have made it at the time.[119]

The Alien Quadrilogy set earned Alien a number of new awards and nominations. It won DVDX Exclusive Awards for Best Audio Commentary and Best Overall DVD, Classic Movie, and was also nominated for Best Behind-the-Scenes Program and Best Menu Design.[120] It also won a Saturn Award for Best DVD, and was nominated for Best DVD Collection and Golden Satellite Awards for Best DVD Extras and Best Overall DVD.[121] In 2010 both the theatrical version and Director's Cut of Alien were released on Blu-ray Disc, as a stand-alone release and as part of the Alien Anthology set.[122]

In 2014, to mark the film's 35th anniversary, a special re-release boxed set named Alien: 35th Anniversary Edition, containing the film on Blu-ray, a digital copy, a reprint of Alien: The Illustrated Story, and a series of collectible art cards containing artwork by H.R. Giger related to the film, was released.[123] A soundtrack album was released, featuring selections of Goldsmith's score. Additionally, a single of the Main Theme was released in 1980,[70] and a disco single using audio excerpts from the film was released in 1979 on the UK label Bronze Records by a recording artist under the name Nostromo.[124] Alien was re-released on Ultra HD Blu-ray and 4K digital download on April 23, 2019, in honor of the film's 40th anniversary.[125] The 4k Blu-ray Disc presents the film in 2160p resolution with HDR10 high-dynamic-range video. Several previously released bonus features on the 4k Blu-ray include audio commentary from director Ridley Scott, cast and crew, the final isolated theatrical score and composer's original isolated score by Jerry Goldsmith, and deleted and extended scenes.[126]

Cinematic analysis

[edit]Critics have analyzed Alien's sexual overtones. The film is often cited as a major work of abjection, as outlined by Julia Kristeva in her 1980 work Powers of Horror. According to Kristeva, the abject refers to that which signifies the breakdown of conventional borders and rules. It confronts the subject with the fallibility of the human body and societal norms, and thus exposes how the supposedly sacred distinctions between what is Self and what is Other are arbitrary.[127] She suggests that this confrontation—often manifesting in excrement, bodily invasion, and corpses—is an inherently traumatic interruption of subjectivity, and thus all evidence of abjection is hidden in conventional society. Much of Alien's effectiveness as a work of horror has been attributed to its indulgence in abject themes and imagery and has thus functioned as a major framework for critics, such as Barbara Creed, in their analysis of the film. Following Creed's assertion that the alien creature is a representation of the "monstrous-feminine as archaic mother",[128] Ximena Gallardo C. and C. Jason Smith compared the facehugger's attack on Kane to a male rape and the chestburster scene to a form of violent birth, noting that the alien's phallic head and method of killing the crew members add to the sexual imagery.[129][130] Dan O'Bannon, who wrote the film's screenplay, has argued that the scene is a metaphor for the male fear of penetration, and that the "oral invasion" of Kane by the facehugger functions as "payback" for the many horror films in which sexually vulnerable women are attacked by male monsters.[131] David McIntee claims that "Alien is a rape movie as much as Straw Dogs (1971) or I Spit on Your Grave (1978), or The Accused (1988). On one level, it's about an intriguing alien threat. On one level it's about parasitism and disease. And on the level that was most important to the writers and director, it's about sex, and reproduction by non-consensual means. And it's about this happening to a man."[132] He notes how the film plays on men's fear and misunderstanding of pregnancy and childbirth, while also giving women a glimpse into these fears.[133]

Film analyst Lina Badley has written that the alien's design, with strong Freudian sexual undertones, multiple phallic symbols, and overall feminine figure, provides an androgynous image conforming to archetypal mappings and imageries in horror films that often redraw gender lines.[134] O'Bannon described the sexual imagery as overt and intentional: "I am going to put in every image I can think of to make the men in the audience cross their legs. Homosexual oral rape, birth. The thing lays its eggs down your throat, the whole number."[135]

Alien's roots in earlier works of fiction have been analyzed and acknowledged extensively by critics. The film has been said to have much in common with B movies such as The Thing from Another World (1951),[54][137] Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954),[138] It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958),[36][82] Night of the Blood Beast (1958),[139] and Queen of Blood (1966),[140] as well as its fellow 1970s horror films Jaws (1975) and Halloween (1978).[54] Literary connections have also been suggested: Philip French of the Guardian has perceived thematic parallels with Agatha Christie's And Then There Were None (1939).[137] Many critics have also suggested that the film derives in part from A. E. van Vogt's The Voyage of the Space Beagle (1950), particularly its stories "The Black Destroyer", in which a cat-like alien infiltrates the ship and hunts the crew, and "Discord in Scarlet", in which an alien implants parasitic eggs inside crew members which then hatch and eat their way out.[141][142] O'Bannon denies that this was a source of his inspiration for Alien's story.[30] Van Vogt in fact initiated a lawsuit against 20th Century Fox over the similarities, but Fox settled out of court.[143]

Several critics have suggested that the film was inspired by Italian filmmaker Mario Bava's cult classic Planet of the Vampires (1965), in both narrative details and visual design.[144] Rick Sanchez of IGN has noted the "striking resemblance"[145] between the two movies, especially in a celebrated sequence in which the crew discovers a ruin containing the skeletal remains of long-dead giant beings, and in the design and shots of the ship itself.[146] Cinefantastique also noted the remarkable similarities between these scenes and other minor parallels.[146] Robert Monell, on the DVD Maniacs website, observed that much of the conceptual design and some specific imagery in Alien "undoubtedly owes a great debt" to Bava's film.[147] Despite these similarities, O'Bannon and Scott both claimed in a 1979 interview that they had not seen Planet of the Vampires;[148] decades later, O'Bannon would admit: "I stole the giant skeleton from the Planet of the Vampires."[149]

Writer David McIntee, as well as reviewers for PopMatters and Den of Geek, have noted similarities to the Doctor Who serial The Ark in Space (1975), in which an insectoid queen alien lays larvae inside humans which later eat their way out, a life cycle inspired by that of the ichneumon wasp.[30][150][151] McIntee also noted similarities between the first half of the film, particularly in early versions of the script, to H. P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness, "not in storyline, but in dread-building mystery",[152] and calls the finished film "the best Lovecraftian movie ever made, without being a Lovecraft adaptation", due to its similarities in tone and atmosphere to Lovecraft's works.[55] In 2009, O'Bannon said the film was "strongly influenced, tone-wise, by Lovecraft, and one of the things it proved is that you can't adapt Lovecraft effectively without an extremely strong visual style ... What you need is a cinematic equivalent of Lovecraft's prose."[153] H. R. Giger has said he liked O'Bannon's initial Alien storyline "because I found it was in the vein of Lovecraft, one of my greatest sources of inspiration."[154]

Audience research

[edit]Findings from an international audience research project conducted by staff from Aberystwyth University, Northumbria University and University of East Anglia were published in 2016 by Palgrave Macmillan as Alien Audiences: Remembering and Evaluating a Classic Movie. 1,125 people were surveyed about their memories and opinions of the film in order to test some of the theories offered by academics and critics about why the film became so popular and why it has endured for so long as a masterpiece. The study discusses memories of Alien in the cinema and on home video from the point of view of everyday audiences, describing how many fans share the film with their children and the shocking impact of the "chestburster" scene, among other things.[155]

Re-release

[edit]For its 45th anniversary, Alien was re-released in theaters by 20th Century Studios in April 2024.[156][157]

Legacy

[edit]Critical reassessment

[edit]In a 1980 episode of Sneak Previews discussing science fiction films of the 1950s and 1970s, the reviewers were critical of Alien. Roger Ebert reiterated Gene Siskel's earlier opinion, stating that the film was "basically just an intergalactic haunted house thriller set inside a spaceship". He described it as one of several science fiction pictures that were "real disappointments" compared to Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and 2001: A Space Odyssey. However, in both episodes Ebert singled out the early scene of the Nostromo's crew exploring the alien planet for praise, calling the scene "inspired", said that it showed "real imagination" and claimed that it transcended the rest of the film.[158] Over two decades later, Ebert had revised his opinion, including the film on his Great Movies list, where he gave it four stars and said it was "a great original".[159] In 1980, Alien was included in Cinefantastique's list of the top films of the 1970s but failed to make the top ten.[clarification needed] Frederick S. Clarke, the Cinefantastique editor, wrote that Alien was "an exercise in style, refreshingly adult in approach, wickedly grim and perverse, that manages to compensate for a lack of depth in both story and characters".[160][verification needed] In 1982, John Simon of the National Review praised the cast, particularly Weaver, and the visual values. He wrote: "For fanciers of horror, among whose numbers I do not count myself, Alien is recommendable, provided they are free from hypocrisy and finicky stomachs".[161]

Despite initial mixed reviews, Alien has received critical acclaim over the years, particularly for its realism and unique environment,[82] and is cited one of the best films of 1979.[162][163] It is seen as one of the most influential science-fiction films.[164][165] It holds a 93% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 203 reviews and an average rating of 9.1/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "A modern classic, Alien blends science fiction, horror and bleak poetry into a seamless whole."[166] Metacritic reports a weighted average score of 89 out of 100 based on 34 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[167] Halliwell's Film Guide awarded it a full four stars, describing it as "a classic of suspense and art direction".[107] Alan Jones of Radio Times awarded it five out of five, describing it as a "revolutionary 'haunted house in space' thrill-ride [...] stunning you with shock after shock", praising the "top-notch acting [...] and imaginative bio-mechanical production design", as well as "Ridley Scott's eye for detail and brilliant way of alternating false scares with genuine jolts, which help to create a seamless blend of gothic horror and harrowing science fiction".[168]

Critical interest in the film was re-ignited with the theatrical release of the "Director's Cut" in 2003. Roger Ebert ranked it among "the most influential of modern action pictures" and praised its pacing, atmosphere, and settings:

One of the great strengths of Alien is its pacing. It takes its time. It waits. It allows silences (the majestic opening shots are underscored by Jerry Goldsmith with scarcely audible, far-off metallic chatterings). It suggests the enormity of the crew's discovery by building up to it with small steps: The interception of a signal (is it a warning or an SOS?). The descent to the extraterrestrial surface. The bitching by Brett and Parker, who are concerned only about collecting their shares. The masterstroke of the surface murk through which the crew members move, their helmet lights hardly penetrating the soup. The shadowy outline of the alien ship. The sight of the alien pilot, frozen in his command chair. The enormity of the discovery inside the ship ("It's full of ... leathery eggs ...").[54]

David A. McIntee praises Alien as "possibly the definitive combination of horror thriller with science fiction trappings."[55] He notes that it is a horror film first and a science fiction film second, since science fiction normally explores issues of how humanity will develop under other circumstances. Alien, on the other hand, focuses on the plight of people being attacked by a monster: "It's set on a spaceship in the future, but it's about people trying not to get eaten by a drooling monstrous animal. Worse, it's about them trying not to get raped by said drooling monstrous animal."[55] Along with Halloween and Friday the 13th (1980), he describes it as a prototype for the slasher film genre: "The reason it's such a good movie, and wowed both the critics, who normally frown on the genre, and the casual cinema-goer, is that it is a distillation of everything that scares us in the movies."[55] He also describes how the film appeals to a variety of audiences: "Fans of Hitchcockian thrillers like it because it's moody and dark. Gorehounds like it for the chest-burster. Science fiction fans love the hard science fiction trappings and hardware. Men love the battle-for-survival element, and women love not being cast as the helpless victim."[169]

David Edelstein wrote, "Alien remains the key text in the 'body horror' subgenre that flowered (or, depending on your viewpoint, festered) in the seventies, and Giger's designs covered all possible avenues of anxiety. Men traveled through vulva-like openings, got forcibly impregnated, and died giving birth to rampaging gooey vaginas dentate — how's that for future shock? This was truly what David Cronenberg would call 'the new flesh,' a dissolution of the boundaries between man and machine, machine and alien, and man and alien, with a psychosexual invasiveness that has never, thank God, been equaled."[170]

In 2008, the American Film Institute ranked Alien the seventh-best science fiction film as part of AFI's 10 Top 10, a CBS television special ranking the greatest movies in ten classic American film genres. The ranks were based on a poll of over 1,500 film artists, critics, and historians, with Alien ranking just above Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and just below Scott's other science fiction film Blade Runner (1982).[171] The same year, Empire named Alien the 33rd-greatest film, based on a poll of 10,200 readers, critics, and members of the film industry.[172] In 2021, Phil Pirrello of Syfy named it the second-scariest science fiction film. He described it as a "groundbreaking science fiction classic" and "a movie so influential that it's hard to think of a time before Alien".[173]

Cultural influences

[edit]

"The 1979 Alien is a much more cerebral movie than its sequels, with the characters (and the audience) genuinely engaged in curiosity about this weirdest of lifeforms...Unfortunately, the films it influenced studied its thrills but not its thinking."[54]

Alien had both an immediate and long-term impact on the science fiction and horror genres. Shortly after its debut, Dan O'Bannon was sued by another writer named Jack Hammer for allegedly plagiarising a script entitled Black Space. However, O'Bannon was able to prove that he had written his Alien script first.[174] In the wake of Alien's success, a number of other filmmakers imitated or adapted some of its elements, sometimes by using "Alien" in titles. One of the first was The Alien Dead (1979), which had its title changed at the last minute to cash in on Alien's popularity.[175] Contamination (1980) was initially going to be titled Alien 2 until 20th Century Fox's lawyers contacted writer/director Luigi Cozzi and made him change it. The film built on Alien by having many similar creatures, which originated from large, slimy eggs, bursting from characters' chests.[175] An unauthorized sequel to Alien, titled Alien 2: On Earth, was released in 1980 and included alien creatures which incubate in humans. Other science fiction films of the time that borrowed elements from Alien include Galaxy of Terror (1981), Inseminoid (1981), Forbidden World (1982), Xtro (1982), and Dead Space (1991).[175]

The "chestburster" effect was parodied in Mel Brooks's comedy Spaceballs. Near the end, in a diner, John Hurt does a cameo appearance as a customer who seems to be suffering indigestion. He turns out to have an "alien" in his gut, and moans, "Oh, no...not again!" The "alien" then does a song-and-dance, singing a line of "Hello, Ma Baby", from the classic Warner Bros. cartoon One Froggy Evening.[176]

Nintendo's long-running Metroid video game series, created in 1986, was significantly influenced by Alien, both in stylistic and thematic elements. As an homage to Alien, villains in the first Metroid installment were named Ridley and Mother Brain, after the movie's director and the ship computer, respectively.[177]

Notably, at Paisley Abbey, during a restoration project that took place in the 1990s, a stonemason from Edinburgh hired to replace twelve crumbling stone gargoyles erected one bearing a strong resemblance to the space creature from the film.[178][179] A picture of the gargoyle went viral in 2013, though a photograph of the statue first surfaced on the internet in 1997.[180] In 2002, it was confirmed the abbey would be subject to a 10-year-long restoration project.

In SFR Yugoslavia the film and its sequels were distributed under the title Osmi putnik (transl. Eighth Traveller).[181] The highly popular Yugoslav and later Croatian hard rock band Osmi Putnik chose their name after the film.[182]

In 2002, Alien was deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant" by the National Film Preservation Board of the United States,[183] and was inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress for historical preservation alongside other films of 1979 including All That Jazz, Apocalypse Now, The Black Stallion, and Manhattan.[184][185]

In 2019, author J. W. Rinzler published The Making of Alien, a behind-the-scenes book about the making of the film with cast and crew interviews and previously unseen photographs. The Verge praised the book as "the definitive story of the classic horror film".[186]

Eli Roth cites Alien as his primary influence, saying "I saw Alien when I was 8 years old. To me, it was like a combination of Jaws and Star Wars and that's the movie that made me want to be a director. It traumatized me. I actually threw up I was so nervous after I saw it but that's like the highest compliment you can give a horror film."[187] Ty Franck, one of the authors behind the sci-fi series The Expanse, credits Alien as one of his major inspirations.[188]

Merchandise

[edit]Alan Dean Foster wrote a novelization of the film in both adult and "junior" versions, which was adapted from the film's shooting script.[64] Heavy Metal magazine published Alien: The Illustrated Story, a graphic novel adaptation of the film scripted by Archie Goodwin and drawn by Walt Simonson, as well as a 1980 Alien calendar.[64] Two behind-the-scenes books were released in 1979 to accompany the film. The Book of Alien contained many production photographs and details on the making of the film, while Giger's Alien contained much of H. R. Giger's concept artwork for the movie.[64] A model kit of the alien, 12 inches high, was released by the Model Products Corporation in the United States, and by Airfix in the United Kingdom.[115] Kenner also produced a larger-scale Alien action figure, as well as a board game in which players raced to be first to reach the shuttle pod while Aliens roamed the Nostromo's corridors and air shafts.[115] Official Halloween costumes of the alien were released in October 1979.[115]

School play adaptation

[edit]In 2019, students at North Bergen High School in New Jersey adapted the film into a play. The production had no budget, with props and sets developed from recycled toys and other items. Social media recognition brought Scott's attention to the play. He wrote a letter of congratulations to the students ("My hat comes off to all of you for your creativity, imagination, and determination") and recommended they consider an adaptation of his film Gladiator for their next stage production.[189] He donated to the school to put on an encore performance at which Weaver was in attendance. She got on stage before the performance to congratulate the cast and crew for their creativity and commitment.[190]

Video game adaptation