Alfonso Carlos de Borbón

| Alfonso Carlos | |

|---|---|

In 1877 | |

| Carlist pretender to the Spanish throne as Alfonso Carlos I | |

| Pretence | 2 October 1931 – 29 September 1936 |

| Predecessor | Jaime III |

| Successor | Disputed |

| Legitimist pretender to the French throne | |

| Pretence | 2 October 1931 – 29 September 1936 |

| Predecessor | Jaime de Borbón y de Borbón-Parma |

| Successor | Alfonso XIII of Spain |

| Born | 12 September 1849 London, England |

| Died | 29 September 1936 (aged 87) Vienna, Austria |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Infanta Maria das Neves of Portugal |

| House | Bourbon |

| Father | Juan de Borbón y Braganza |

| Mother | Maria Beatrix of Austria-Este |

| Signature |  |

Alfonso Carlos de Borbón (12 September 1849– 29 September 1936) was the Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain under the name Alfonso Carlos I; some French Legitimists declared him also the king of France as Charles XII, though Alfonso never officially endorsed these claims.

In 1870 and in the ranks of the papal troops, he defended Rome against the Italian Army. In 1872–1874, he commanded sections of the front during the Third Carlist War. Between the mid-1870s and the early 1930s, he remained withdrawn into privacy, living in his residences in Austria. His public engagements were related to the buildup of an international league against dueling.

Upon the unexpected death of his nephew Jaime de Borbón y de Borbón-Parma in 1931, he inherited the Spanish and French monarchical claims. As an octagenarian he dedicated himself to development of Carlist structures in Spain. He led the movement into the anti-Republican conspiracy, which resulted in Carlist participation in the July coup d'état. As he had no children, Alfonso Carlos was the last undisputable Carlist pretender to the throne; after his death the movement was fragmented into branches supporting various candidates.

Family and youth

[edit]

Alfonso was a descendant of the royal Spanish Borbón family; his great-grandfather was the king of Spain, Carlos IV. Alfonso's grandfather Carlos María Isidro (1788-1855) was engaged in dynastical feud with his brother over inheritance, though the conflict overlapped with major social and political cleavages. The 1833-1840 civil war which ensued produced defeat of Carlos María, who claimed the throne as Carlos V, and of his traditionalist and anti-liberal followers, named Carlists. The claimant went on exile and abdicated in 1845 in favor of his oldest son. His younger son and the father of Alfonso, Juan de Borbón y Braganza (1822-1887), was at the time serving in the army of a relative, King of Sardinia.[1] In 1847 he married Maria Beatrix of Austria-Este, sister to the ruling Duke of Modena, Francisco V; in 1848-1849 the couple had two sons, Alfonso born as the younger one. However, increasingly liberal outlook of Juan produced acute conflict with his religious wife and his brother-in-law, Francisco V. The couple agreed to separate; Juan left for England, while Maria Beatriz with their 2 sons remained in Modena.[2]

In the 1850s Alfonso spent his early childhood with his mother and older brother in the Duchy of Modena; it is there he received his early homeschooling.[3] Due to the revolutionary turmoil of 1859 the family left for Austria, hosted by the ex-emperor, Ferdinand I;[4] they settled in Prague, which remained their key residence until 1864.[5] Their attempt to settle in Venice, resulting from health concerns, was aborted due to the Italo-Austrian war; they spent the years of 1864-1867 shuttling between Innsbruck, Vienna and Graz.[6] Both teenagers were raised in very pious ambience; their religious mother and equally devout but more strong-willed step-grandmother, María Teresa de Braganza, made sure the boys received a profoundly Catholic, Carlist and anti-liberal education.[7] In 1868 Alfonso embarked on a long pilgrimage to Palestine; the same year his 21-year-old brother Carlos assumed the Carlist claim to the throne of Spain.[8] When back in Europe Alfonso decided to join Papal Zouaves.[9]

When on leave from the papal service, in the late 1860s Alfonso met the teenage infanta María das Neves of Braganza (1852-1941).[10] She was the oldest child of deposed king of Portugal Miguel I, who lost the throne in 1834; on exile Miguel wed princess Adelaide of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg, descendant to highly aristocratic German family. Alfonso and María married in 1871 in the bride's family estate at Kleinheubach. The bride and the groom were related, as María's paternal grandmother Carlota Joaquina was sister to Alfonso's paternal grandfather; they obtained the papal dispensation first.[11] The couple turned out to be caring and loving partners;[12] their marriage lasted 65 years. However, they had no descendants. Some sources claim their only child was born in 1874 but died shortly afterwards,[13] others maintain they had no children at all.[14]

Military episode (1870-1874)

[edit]Since enlisting into the Zouavaes during almost 2 years Alfonso Carlos was taking part in trainings, maneuvers and other peacetime service of papal army.[15] When Italian troops assaulted Rome he served as alférez in the 6. Company of the 2. Battalion. It was deployed along Aurelian Walls and concentrated around Porta Pia, on key axis of Italian assault.[16] The fighting took place on 20 September 1870. For a few hours and heavily outnumbered, the Zouaves resisted onslaught of the bersaglieri shock units;[17] some authors refer to the "famous last stand".[18] The papal order to give up[19] was not accepted unanimously and some detachments kept fighting until all units surrendered later that day. Alfonso was neither recognized nor revealed his identity and for 3 days with other POWs he was kept imprisoned; they were then shipped to Toulon and released.[20] He transferred to Graz and got married the following year.

In early 1872 Carlos VII was gearing up for a military rising against the monarchy of Amadeo I. He recalled his brother to southern France and in April nominated him commander of Carlist troops, supposed to operate in Catalonia.[21] While fighting continued[22] Alfonso resided mostly in Perpignan. He focused on logistics and labored to obtain financing;[23] he also made personal military appointments[24] and issued general orders.[25] In late December he crossed into Spain[26] and in February[27] joined the column led by Francisco Savalls.[28] During the next half a year Alfonso was shuttled between small villages in the Girona and Barcelona provinces. It is not clear what was his personal contribution to minor successes in the area;[29] he is better known for organizing events intended to raise spirits.[30] During the summer he developed acute conflict with Savalls;[31] in October 1873 via France[32] Alfonso moved to Navarre to discuss problems in command chain with his brother.[33] Outcome of the talks was inconclusive and until spring of 1874 Alfonso remained in Perpignan.[34]

In April Alfonso returned to Catalonia and set headquarters in Prats de Llusanés.[35] One source claims he turned Carlist structures into a well-lubricated machinery and moved south to consolidate the insurgent rule there.[36] In May he crossed the Ebro[37] and commanded during fighting near Gandesa;[38] in June he turned towards the Maestrazgo and southern Aragón.[39] In July 1874 Alfonso headed the failed siege of Teruel,[40] and later that month he ordered operation against Cuenca. The assault produced one of the largest Carlist triumphs; as one of only 2 provincial capitals, Cuenca was seized by the insurgents.[41] However, victorious troops plundered the city[42] and "Saco de Cuenca" became one of the most notorious cases of Carlist violence.[43] In August 1874 Carlos VII transferred Alfonso to command of the newly created Ejército del Centro;[44] Alfonso protested the decision[45] and resigned.[46] During September and October he remained relatively inactive.[47] With headquarters in Chelva and then Alcora,[48] he issued last orders to organize a raid towards Murcia.[49] With his brother's acceptance in November 1874 Alfonso crossed to France and withdrew into privacy.[50]

Financial status

[edit]

Along paternal line Alfonso inherited little wealth. His father, descendant to exiled branch of Spanish royals, abandoned the family; as a commoner he resided in England and lived off a pension, paid by relatives of his estranged wife.[51] Alfonso's mother initially shared the family Austria-Este wealth in the Duchy of Modena. Once her brother lost the throne the branch lived on exile in Austria and their properties were divided among many members. Upon wedding Alfonso married into wealth of the Braganza family, also exiled from Portugal but possessing numerous estates in Bavaria, Austria and elsewhere. According to a not necessarily trustworthy source Francisco V, who had no sons, intended to make Alfonso his legal heir; the condition was that Alfonso adopts the Austria-Este name, which he refused.[52] As a result of numerous divisions of assets within the Borbón/Austria Este[53] and Braganza/Löwenstein-Wertheim families, Alfonso and his wife ended up as owners of 4 estates, all located in the imperial Austria: a multi-storey residential building at Theresianumgasse in Vienna, the palace in Puchheim, the palace in Ebenzweier and numerous smaller urban estates in Graz.[54]

Until 1914 the couple remained in an excellent financial position. Their source of income was mostly profits generated by rural economy related to the Ebenzweier and Puchheim estates, e.g. the former comprised some 1,000 hectares of forests alone.[55] Their rural possessions were exempted from fiscal and other obligations, as they enjoyed extraterritorial status, granted by the ruling Habsburg branch to own relatives.[56] The rural profits were generated by usual large-scale agricultural businesses, including production and sales of dairies, horticultural products, grain, cattle and even flowers. Other income was produced by rental of premises in Vienna and Graz and by various securities; some of them were issued by institutions operating abroad, e.g. in Russia. In the 1910s and on suggestion of a trusted Spanish adviser, most of these papers were deposed in Swiss banks.[57]

In the Republican Austria the couple suffered financial problems, especially in the early 1920s; they were the result of new social and fiscal regulations, inflation and loss of extraterritoriality. Thanks to efforts of the Madrid diplomacy the privileged status was restored to some estates[58] and Ebenzweier was leased to the Spanish embassy,[59] yet they were still threatened by expropriation. Due to labor legislation the rural economy was barely making any profit,[60] rental became commercially difficult and securities, located abroad, were hardly accessible. Facing total financial breakdown the couple accepted measures like cutting down park trees for timber, regular sales of plots and Graz estates, and even sales of personal belongings like jewelry and art.[61] During a few years they refrained from purchase of new clothing;[62] in Vienna they always travelled on foot[63] and during train journeys they regularly took 3rd class.[64] They reduced personal staff to 3 servants and at time suffered cold due to economizing on heating. In the early 1930s their status improved slightly; political changes in Austria produced less restrictive policy,[65] and as king Alfonso was aided financially by the Carlist organization in Spain.[66]

Lifestyle

[edit]

Both very religious, Alfonso and María made a loving couple;[67] throughout all of their 65-year marriage they stayed close one to another. Unlike his older brother, Alfonso never took part as involved in extra-marital episodes.[68] The couple were only moderately attracted by glitz of the imperial capital; for political reasons they did not have access to official gatherings organized by the Habsburg court.[69] Alfonso used to spend his days behind the desk doing business correspondence.[70] Periodically he was assisted by personal secretary,[71] yet he complained of not having one who could do business in German.[72] In the interwar period he corresponded heavily with Marqués de Vesolla, who turned his principal financial advisor and trustee.[73] In their free time the couple enjoyed long walks; even in their 80s they walked for 2–3 hours,[74] and in Vienna their preferred spot was the Belvederegarten.[75] When younger Alfonso was fond of riding a bicycle.[76] Both enjoyed bullfighting and when in America or Spain they always tried to attend a corrida.[77]

Until 1914 the couple led a luxurious life, shuttling between their estates depending upon season[78] and other circumstances. In each residence they maintained dedicated staff,[79] and when travelling they carried with them servants[80] and numerous belongings, including horses.[81] Since they found winters in Austria severe,[82] around December every year the couple used to depart for warmer regions and returned around April; prior to World War I Alfonso and his wife during 45 successive years travelled to Italy, other Mediterranean (though not Spain) and embarked on longer journeys to America, Africa and the Middle East.[83] Their luggage could have amounted to 95 pieces and 4 tons.[84] Due to financial difficulties the couple ceased travelling after World War One; later they resumed winter journeys,[85] though not to exotic places any more.[86] They travelled incognito and lived very modestly.[87] Since inheriting the Carlist claim in 1931 Alfonso and María used to spend long spells in southern France, next to the Spanish frontier.

If paying visits or being visited, they usually limited themselves to close family.[88] At times they met other relatives, like nephews and nieces.[89] Until 1906 they frequently visited Alfonso's mother, the nun in Graz.[90] In the 20th century they maintained closer links with Alfonso's nephew and the Carlist claimant, Don Jaime; owner of the Frohsdorf palace near Vienna, he used to visit his uncles en route to and from Paris. Their mutual relation was cordial, but Alfonso considered Don Jaime somewhat of a playboy.[91] Despite political and dynastical conflict the couple maintained very correct correspondence with Alfonso XIII, especially that Spanish diplomacy provided them with enormous help after 1918.[92] They reserved enmity only for Berthe, widowed by Alfonso's brother; they thought her an immoral profligate who lived off selling illegally seized belongings.[93] Until the late 1920s they were also lukewarm towards some members of the Borbón-Parma family.[94] From one of their Africa journeys Alfonso and María brought a black girl named Mabrouka;[95] over time she assumed a role in-between a servant and a family member.[96] From 1909 onwards Alfonso kept paying a pension to his English half-siblings.[97]

General political views

[edit]

Alfonso considered himself above all a Spaniard and identified with Spain as "my country";[98] he believed in the Spanish mission in America, where highly spirited Hispanidad was to oppose the mean Anglo-Saxon culture.[99] During incognito journeys to Spain in the 1920s he felt "like in heaven" and cheered gentle, serene, helpful Spaniards.[100] Until 1918 he also felt emotionally highly attached to Austria and wholeheartedly supported the Central Powers during the First World War.[101] However, after the overthrow of the monarchy the sympathy for his host country evaporated, mostly due to the social legislation adopted; he referred to Austria as to his prison.[102] What did not change was Alfonso's Francophobia. Both in great politics and in unfortunate family events he kept tracing treacherous and sinister influence of Paris, controlled by masonic and republican crooks,[103] and lamented apparent French influence over Spain.[104]

Though liberal Spanish press at times named Alfonso "the butcher of Cuenca", referring to his command of Carlist troops which plundered Cuenca following seizure of the city during the Third Carlist War,[105] later on he demonstrated an anti-war and peaceful stance. During the Spanish–American conflict he declared in private that Spain should have abandoned Philippines and Cuba 3 years earlier.[106] He was irritated by what he perceived as hyper-patriotic frenzy of the Spanish press,[107] praised the Madrid government for concluding the peace treaty and claimed it had prevented loss of Canary Islands and Balearic Islands.[108] During the First World War the couple ran a mini-hospital in their Vienna house, and catered personally to wounded soldiers.[109] He deplored revolutionary violence in Russia and elsewhere. When assuming the Carlist claim he confessed that civil war was an unacceptable means of politics.[110] However, he was best known as partisan of the anti-duel movement.[111] In a few countries Alfonso Carlos co-founded and animated leagues against dueling,[112] in some cases he ensured royal patronage, wrote a book which advanced the cause and published a few related articles.[113]

As descendant and heir to deposed rulers he abhorred liberal regimes set up in the second half of the 19th century in Europe. The Soviet revolution remained his constant negative reference point, standing for iconic breakdown of civilization.[114] However, also social-democratic legislation of republican Austria gained his furious criticism, with successive Austrian authorities referred to as "communist" and "bolsheviks" ruling over "the country of thieves who have respect neither for law nor for justice nor for property"; even the Christian-democratic president Miklas was dubbed as "red".[115] He welcomed the Primo dictatorship[116] and later lamented decline of political order in Spain of 1930. He predicted the country would turn a republic within 2 years;[117] when the Alfonsine monarchy indeed fell he viewed the newly set up Second Spanish Republic as a stepping stone towards anarchy and communism.[118] Alfonso viewed the Dollfuss regime in Austria as a step forward, yet his views on the Fascist regime in Italy and the Nazi rule in Germany remain unclear.[119]

Carlist engagements, 1875–1930

[edit]

According to the Carlist dynastical doctrine, upon birth Alfonso was the third in line of succession to the throne.[120] In 1861–1868, he was the second,[121] and in 1868–1870 the first to inherit the claim.[122] Since 1870 he was relegated to the second position, as upon future death of his older brother the claim was supposed to pass to his newly born son and Alfonso's nephew, later known as Don Jaime. When this indeed happened in 1909 Alfonso became again the first in line of succession, but very few looked upon him as a future Carlist king. Though over decades Don Jaime moved from youth to mid-age childless and was aging unmarried, until the late 1920s it was still theoretically possible he would have a legitimate son. Even in case he would not, Alfonso could not have reasonably expected to inherit the claim, as it seemed unlikely that he would outlive his 21-year-junior nephew. Hence, for over half a century within mainstream Carlism Alfonso was viewed as a collateral member of the royal family who gallantly contributed to the cause in the early 1870s, but who would not play any role in the future.

The dissenting factions tended to look towards Alfonso as to a would-be dynastical counter-proposal to either his brother or his nephew almost every time when Carlism suffered from internal crisis. In the mid-1880s supporters of Ramón Nocedal challenged Carlos VII and some nurtured hopes that Alfonso would become their leader;[123] also some French legitimists, following death of Conde de Chambord, considered Alfonso and not his father the next French king.[124] In the late 1890s a faction pressing violent action against the Spanish monarchy faced caution and skepticism on part of the claimant; again, their speculations tended to focus on Alfonso. In the mid- and late 1910s followers of Juan Vázquez de Mella decidedly favored Germany during the Great War; as Don Jaime sympathized with the Entente and Alfonso supported the Central Powers, the latter again became subject of dynastical speculations.[125]

Alfonso never revealed the slightest tone of disloyalty to his ruling relatives and never tried to supersede them or to build his own following in the party. Though he proudly admitted his Carlist identity he remained somewhat detached from the movement,[126] and participated neither in behind-the-scenes meetings forging the Carlist policy nor in large Carlist gatherings held abroad; this stand earned him some criticism and few called him "santo imbécil".[127] He maintained private correspondence with some Carlist personalities in Spain, at times discussed political developments and expressed his own opinions,[128] but there is no evidence he has tried to enforce his views or mount any political schemes. His correspondence neither reveals any speculations or maneuvers related to his future theoretical claim.[129] In the 1920s he started making provisions for his own death[130] and in 1930 he was positive that his nephew remained in good health, with years and maybe decades of "rule" ahead of him.[131]

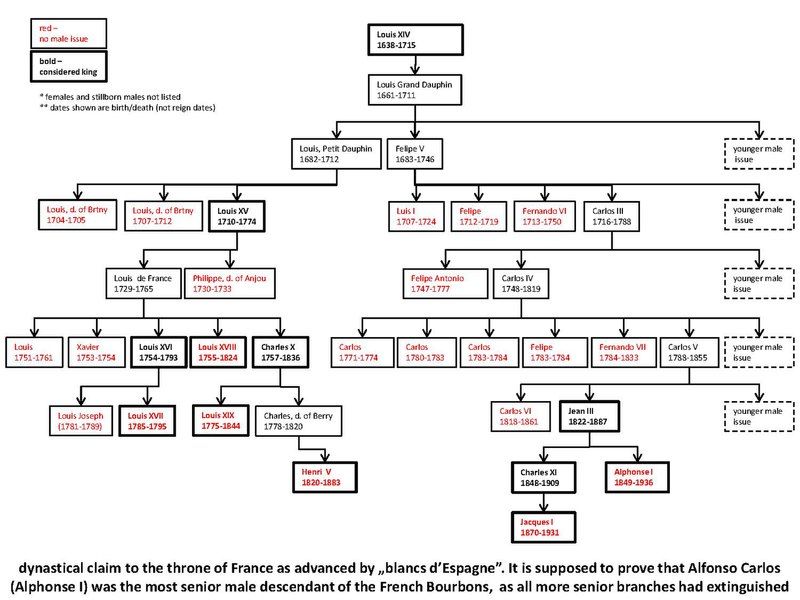

French claim

[edit]Following the unexpected death of his nephew, in October 1931 Alfonso inherited the legitimist claim to the French throne. He has never officially voiced in the French case; he neither endorsed claims by Blancs d'Espagne nor distanced himself from them. The branch related to Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma declared him "Charles XII",[132] while the followers of Paul Watrin opted rather for "Alphonse I".[133] Between 1931 and 1936 Alfonso spent at least 4 winters in the south of France,[134] but he avoided public engagements; the best known was a religious event in Mondonville, highly saturated with legitimist flavor.[135]

Spanish claim

[edit]

With death of Don Jaime in October 1931 Alfonso inherited the Carlist claim to the Spanish throne. He accepted it, though he privately confessed that the decision came as the "largest sacrifice of my life" and that Traditionalist crown was a "crown of thorns".[136] In order not to burn the bridges with the Alfonsists he rejected the royal name of "Alfonso XII"; in order not to alienate the Carlists he rejected also the name of "Alfonso XIV"[137] and eventually settled for the royal name of "Alfonso Carlos I".[138] Traditionally the Carlist claimants assumed also the title of Duque de Madrid. Because of Berthe de Rohan, widow after Carlos VII who still bore the title of Duquesa de Madrid, Alfonso Carlos eventually opted for the title of Duque de San Jaime.[139] He confirmed en bloc all earlier personal party nominations of Don Jaime;[140] however, in late 1931 for few months he settled in France to discuss things in detail.[141]

Alfonso Carlos initially seemed ready to discuss an informal dynastic solution, tentatively agreed between Don Jaime and the deposed Alfonso XIII as so-called Pact of Territet. He met Alfonso in France and both issued warmly-worded manifestos, though with little substance.[142] This triggered anxiety among the Carlist branch known as the cruzadistas; during the meeting with Alfonso Carlos in mid-1932 they seemed to have arrived at some understanding,[143] but as the cruzadistas became intransigent, he expelled them from the party.[144] In 1933–1934 Alfonso Carlos grew clearly disinclined toward a dynastic agreement;[145] in 1934 he also dismissed potential claim of his grandnephew Karl Pius.[146] In 1935 Alfonso Carlos welcomed Don Alfonso in Puchheim, but they focused on family issues.[147] After final hesitation[148] in April 1936 Alfonso Carlos made public his decision;[149] following his death prince Xavier[150] would become a regent, who as soon as possible and following consultation with a grand Carlist assembly would decide upon the next king.[151]

Another paramount issue Alfonso Carlos had to deal with was the Carlist stand towards the Spanish Republic. He despised the regime as a first step towards bolshevism,[152] yet it is not clear to what extent he shaped Carlist daily politics of 1931–1936. He presided over re-unification of Traditionalism; some claim that as personally he was leaning towards Integrism,[153] former Integrists became overrepresented in command.[154] Some claim that already in 1932 he engaged in plans for a "combined monarchist rising", which have eventually fizzled out.[155] Following death of the party jefé Marqués de Villores in 1932 he appointed a moderate successor, Conde Rodezno, and with little enthusiasm authorized his tactics of entering into ongoing political parliamentary co-operation with Alfonsists in the National Bloc.[156] However, since 1933 he was increasingly impressed by the local Andalusian leader Manuel Fal Conde,[157] who advanced intransigent and increasingly militant anti-republican course. In 1934 Fal replaced Rodezno as Secretary General, and in 1935 he assumed the role of Jefé Delegado.[158] Under his guidance and with full approval on part of Alfonso Carlos the party withdrew from the National Bloc and embarked on a stand-alone, non-compromise course.[159]

Last months

[edit]

No source clarifies what was Alfonso Carlos' position versus massive Carlist paramilitary buildup in 1935–1936. Since late 1935 he resided in Guéthary in southern France[160] and until early summer of 1936 he supervised personally Carlist conspiracy plans and their negotiations with the military,[161] approving of conditions that Fal presented to head of rebellious generals, Mola.[162] On 28 June, and for reasons which are not entirely clear, he left Saint Jean de Luz and headed for Vienna,[163] leaving prince Xavier to manage daily politics. From then on it was Xavier who supervised Carlist conspiracy and talks with the military. Alfonso Carlos' approval was sought remotely on most outstanding issues;[164] it is known that he explicitly prohibited any local Navarrese negotiations.[165] Following vague agreement reached in talks with Mola, the final order to rise was issued by prince Xavier in name of Alfonso Carlos. An emissary was immediately flown to Vienna to obtain confirmation; when it arrived the coup was already in full swing.[166]

Alfonso Carlos issued a royal decree which dissolved all Carlist regular executive structures and replaced them with wartime Juntas de Guerra, including the central one.[167] However, from his residence at Theresianumgasse in the Austrian capital the claimant had little further control over the events unfolding. His known statements are mostly enthusiastic acknowledgements of Carlist military effort. One of the very last of his documents was the telegram message with greetings to the requeté detachment known as "40 de Artajona", which on 13 September as the first Nationalist unit entered the captured city of San Sebastián.[168] Similarly, he acknowledged that a hospital in Pamplona had been named after him and that one Carlist militia battalion had been named after his wife.[169] He was impressed with requeté buildup and rather optimistic as to the outcome of the conflict;[170] in his letter of 22 September he declared that "la gloria de nuestros requetés será haber salvado a España y a Europa".[171] No other type of his activity – e.g. in terms of seeking diplomatic support or ensuring financial aid – is known.

On 28 September 1936 Alfonso Carlos and his wife as usual decided to take a daily walk in the nearby Belvederegarten. When crossing Prinz Eugen Strasse, with the garden nearby on the other side of the street, the 87-year-old behaved erratically; he stopped in the middle of the tram track, then attempted to run, and was eventually hit by a car approaching from Schwarzenbergplatz.[172] He was immediately taken to the hospital and emergency team was assembled to treat him; following slight improvement in the evening,[173] he perished the following day. One historian speculates – given 12 hours difference between the death of Alfonso Carlos and Franco's ascendance to caudillo – that the collision might not have been accidental.[174] The funeral and burial in the family chapel in Puchheim was attended by the widow – who emerged unhurt from the accident, by prince Xavier, many aristocratic family members[175] and the Carlist executive, which in corpore[176] travelled by train from the war-engulfed Spain.[177]

Reception and legacy

[edit]

In the Spanish public discourse of the late 19th century Alfonso Carlos featured as an iconic villain, one of a few key protagonists of Carlist atrocities. In the post-war liberal propaganda "saco de Cuenca" played similar role as "masacre de Badajoz" did in the Republican propaganda after the Civil War of 1936–1939; it marked the climax of barbarity, and Alfonso Carlos was held personally responsible for it. Canovas formally requested his extradition from France[178] and in 1878 a book Los sucesos de Cuenca delivered a horror picture of Carlist savagery.[179] In the 1890s a series of popular pamphlets Los crímenes del carlismo by José Nakens repeatedly presented Alfonso Carlos as instigator of various bloody episodes.[180] As late as 1900 the press referred to him as "odioso asesino de Cuenca".[181] The Galdós' novel De Cartago a Sagunto (1911) renewed his image of a blood-stained criminal commander.[182] As somewhat more ambiguous figure he was marginally referred to in great Spanish modernist literature of Unamuno[183] and Baroja.[184] In much less popular Carlist narrative he was hailed as former gallant military leader and member of the royal family.[185]

In the early 20th century the anti-duel activity of Alfonso Carlos earned him some moderate recognition,[186] though not in Spain, where he fell into oblivion. When in 1931 the Spanish press reported on his assumption of the Carlist claim, most titles felt it appropriate to explain to their readers who the person in question was; some noted literally that "there is an uncle of Don Jaime alive, named Alfonso de Borbón, who lives in Austria".[187] It was only sporadically that some titles kept referring to "saqueador de Cuenca",[188] though for elderly pundits like Unamuno he still remained "don Alfonso Carlos, el de Cuenca".[189] On the other hand, the Traditionalist propaganda machinery launched a campaign of exaltation, hailed "nuestro augusto caudillo"[190] and constructed a panegyric mediatic image of the pretendent.[191]

Alfonso Carlos' memory did not feature prominently in the fragmented post-war Carlism. The Javieristas used to refer to his 1936 regency decision as to legitimization of Don Javier's leadership; some others concluded that with death of Alfonso, the Carlist dynasty extinguished and Carlism came to the end.[192] In the Francoist propaganda he was absent and did not feature in the gallery of Nationalist heroes, as the regime was cautious to enforce official unity and to contain excessive Carlist idolization.[193] Sort of documentary historiographic approximation was offered by Melchor Ferrer in 1950.[194] Ferrer also focused in detail on Alfonso Carlos leadership in the final volume of his monumental series on history of Carlism. It was edited posthumously and issued in 1979;[195] the same year its excerpts were published as a separata under the title of Don Alfonso Carlos de Borbón y Austria-Este. Until the early XXI century it remained the only monograph dedicated to the claimant;[196] Alfonso Carlos failed to trigger historiographic interest and is missing even in detailed accounts on recent history of Spain.[197] Historiography on Carlism tends to focus on his 1936 regency decision, the move which fundamentally affected the fate of the movement for decades to come.[198] In 2012 editors of Alfonso Carlos' diary prefaced it with a 66-page biography, which is currently the best account available.[199]

Publications

[edit]- "The Effort to Abolish the Duel", The North American Review 175 (August 1902): 194–200.

- "The Fight Against Duelling in Europe", The Fortnightly Review 90 (1 August 1908): 169–184.

- Resumé de l'histoire de la création et du développement des ligues contre le duel et pour la protection de l'honneur dans les différents pays de l'Europe de fin novembre 1900 à fin octobre 1908 (Vienna: Jasper, 1908). German translation: Kurzgefasste Geschichte der Bildung und Entwicklung der Ligen wider den Zweikampf und zum Schutze der Ehre in den verschiedenen Ländern Europas von Ende November 1900 bis 7. Februar 1908 (Vienna: J. Roller, 1909).

- Documentos de D. Alfonso Carlos de Borbon y de Austria-Este (Madrid: Editorial Tradicionalista, 1950).

Ancestry

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ he rose to the rank of mayor general, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXII, Sevilla 1958, pp. 10, 12

- ^ Ferrer 1958, pp. 17-18

- ^ it was provided by carefully selected and highly religious preceptors, Ferrer 1958, p. 152, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXX/1, Sevilla 1979, p.

- ^ Ferrer 1958, p. 130

- ^ Ferrer 1958, pp. 130-131

- ^ Ferrer 1979, p. 9

- ^ Ferrer 1958, pp. 153-154

- ^ Ferrer 1979, p. 9

- ^ he obtained permission from his mother first, Ferrer 1979, pp. 9-10

- ^ at the time she was receiving education at the Sacré-Cœur convent, Ferrer 1979, p. 9

- ^ Ferrer 1979, p. 11

- ^ Ferrer 30/1 12-14

- ^ Ignacio Miguéliz Valcarlos (ed.), Una mirada intima al dia a dia del pretendiente carlista, Pamplona 2017, ISBN 9788423534371. p. 21

- ^ Carlos Robledo do Campo, Los infantes de España tras la derogación de la Lay Sálica (1830), [in:] Anales de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía XII (2009), p. 345. The only existing monograph on Maria das Neves does not discuss the question of her giving birth, Miguel Romero Sans, Dona Blanca. Una reina sin corona bajo el carlismo, Cuenca s.d., ISBN 9788495414786

- ^ Ferrer 1979, p. 9

- ^ Ferrer 1979, pp. 9-10

- ^ see e.g. La battaglia di Porta Pia, [in:] Emanuele Martinez, Il Museo Storico di Bersaglieri, Roma 2020, ISBN 9788849289572, pp. 28-29

- ^ J. A. Mirus, Faith and Reason, New York 1990, p. 367

- ^ when the Italian artillery fire produced a breach in the walls and the bersaglieri started to pour in, the Pope decided to abandon resistance, Josep Powell, Two Years in the Pontificial Zouaves, London 1871, p. 298

- ^ Ferrer 1979, p. 11

- ^ Ferrer 1958, p. 36

- ^ Alfonso was barely engaged in military actions; isolated insurgent columns were operating independently and commanded by own leaders, Ferrer 1958, p. 119 and onwards

- ^ which came mostly from his relatives; Duque of Modena, Condesa de Montizón and the Lowenstein family, Ferrer 1958, pp. 37-42

- ^ Ferrer 1958, p. 102

- ^ e.g. in December 1872 Alfonso issued an order which declared expulsed from the royal army and unfaithful to the cause all these who were once Carlists but did not join insurgent troops by mid-January, Ferrer 1958, p. 54

- ^ it took significant effort to deceive the French security, Ferrer 1958, p. 44. The same author claims in another work that Alfonso crossed to Spain in January 1873, Melchor Ferrer, Breve historia del legitimismo español, Sevilla 1958 [from now on referred as Ferrer 1958b], p. 62

- ^ in January Alfonso resided in small villages on southern slopes of the Pyrenees, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español vol. XXV, Sevilla 1958 [from now on referred as Ferrer 1958c], p. 94

- ^ Ferrer 1958c, p. 94

- ^ like seizure of Ripoll, or victories during skirmishes at Oristá, Alpens and Igualada, Ferrer 1958c pp. 97, 101, 102

- ^ e.g. he presided over an amassment of 3,000 troops in Montserrat, when units were dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Ferrer 1958c, p. 100

- ^ apart from personal incompatibility between the 55-year-old military and the 24-year-old inexperienced infant the conflict reportedly resulted from different visions of warfare; Savalls preferred a guerilla strategy and Alfonso opted for more regular operations, Ferrer 1958c, p. 107. Also, Alfonso protested ruthless treatment of prisoners, practiced by Savalls; the conflict started in March, during executions ordered by Savalls in Ripoll, Ferrer 1958c, p. 97. Another similar incident followed in Berga, Ferrer 1958c, p. 107

- ^ Aragón, which separated the Carlist units operating in Catalonia and the Carlist-held territory in Navarre, was firmly controlled by governmental troops. Alfonso moved to Perpignan, travelled by train to Bourdeaux, and then crossed to Navarre, Ferrer 1958c, p. 108

- ^ Ferrer 1958c, p. 108

- ^ at least theoretically Alfonso remained in command of Carlist troops in Catalonia. In Perpignan he received visits of Carlist commanders and imposed disciplinary measures against Savalls, who was ordered to spend 3 weeks off-duty in France, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXVI, Sevilla 1959, p. 150

- ^ also in Prats de Llusanés Alfonso organized solemn ceremonies, Ferrer 1959, p. 158

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 198. Indeed, Alfonso is recognized e.g. for efforts to build Carlist postal service in the area, Gerhard Lang-Valchs, El correo carlista en el Maestrazgo, [in:] Millars 43 (2017), p. 255

- ^ his group consisted of general staff and a battalion of Zouaves that he personally raised and paid for, Miguel Romero Saiz, "El saco de Cuenca". Boinas rojas bajo la mangana, Cuenca 2010, ISBN 978-84-92711-76-5, p. 15

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 188

- ^ Ferrer 1959, pp. 188-190

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 190. Infante blamed the Aragón commander Manuel Marco and relieved him from command, much to resentment of his troops, Ferrer 1959, p. 191

- ^ also, some 2,200 prisoners were taken

- ^ some defenders were executed and some residents were murdered during the looting; total number of those killed is estimated between 50 and 100, compare Romero Saiz 2010

- ^ the "Saco de Cuenca" for decades sustained liberal propaganda, which presented the movement as cruel brutes obsessed with violence, Ferrer 1959, pp. 247-248, Exact role of Alfonso in the episode is not clear. As he was in command of the troops and shortly resided in the city himself, many deemed him personally responsible for the carnage and later the prime minister Canovas demanded Alfonso's extradition for war crimes. However, Carlist historians claim he actually tried to ensure law and order, compare Ferrer 1959, pp. 246-256. In September 1874 Alfonso spoke against a no-mercy war and issued an order that "todo herido o enfermo enemigo que encuentren, debe ser sagrado, y que respetaran su mansión y persona", Ferrer 1959, p. 194

- ^ the Army of Centre was partially carved out from the Army of Catalonia. Alfonso was made its capitán general, Ferrer 1959, p. 199. The move is viewed as an attempt to sort out conflict between Alfonso and Savalls, as Carlos VII was not prepared to remove neither his brother nor the very efficient and experienced military commander

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 65

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 176. Also many Catalans did not want to fight beyond their home Catalonia, Ferrer 1959, p. 198

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 199

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 200

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 195

- ^ Alfonso had to cover some 320 kilometres from Alcora via Gandesa, Flix, Juncosa, Seo de Urgell and Andorra, Ferrer 1959, pp. 176, 200

- ^ Richard Thornton, La esposa y la familia británica desconocidas del pretendiente Carlista don Juan de Borbón, [in:] Anales de la Real Academia Matritense de Historia y Genealogía XII (2009), p. 425

- ^ Francisco Melgar, Veinte años con Don Carlos, Madrid 1940, p. 100. Eventually Francisco V made archduke Franz Ferdinand his heir

- ^ the pearl among Borbón/Austria Este properties was the Loredan palace in Venice, acquired by Alfonso's mother in 1859. It went to his older brother Carlos, and was later inherited by his wife, Berthe de Rohan

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 31-32. Though Alfonso and his wife owned numerous estates in Graz, when in the city they lived mostly in "Villa Nieves", in a large estate with a few buildings at intersection of Humboldtstraße and Goethestraße. The building was demolished in 1959, though the adjacent one, reportedly where the servants lived, still stands, Villa Nieves, [in:] Grazwiki service, available here

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 443; an estate of 43 ha was considered by Alfonso Carlos "pequeño pedazo de terreno", Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 137

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 212

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 441

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 257

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 134, 164

- ^ for discussion on sale of milk, wood, grain or cattle see Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 207, 306, 335

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 365, 368, 392

- ^ e.g. between 1913 and 1921, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017,

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 163

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 233

- ^ while in the 1920s Alfonso Carlos in private correspondence regularly referred to the Austrian authorities as "bolsheviks", "communists" or "reds", in the early 1930s he noted that "aquí el Gobierno es excelente", Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 479

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 462

- ^ upon wedding they prayed that God would allow them to pass away together

- ^ though an Austrian website claims that "Das Wohnhaus Körblergasse 20 [in Graz] gilt als das Haus der Mätressen des Infanten", with no source provided, Villa Nieves, [in:] Grazwiki service, available here

- ^ the Vienna Habsburgs were closely related to María Cristina, first queen regent and then queen mother in Madrid, part of the competitive Alfonsist dynasty

- ^ at times Alfonso was responding to 20 letters a day, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 396

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 458

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 92

- ^ some 80% of some 200 letters exchanged between Alfonso Carlos and de Vesolla is related to finances, compare Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017. Most securities moved by Alfonso to Swiss banks were deposed on name of de Vesolla

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 467

- ^ Belvederegarten is located close to Theresianumgasse, where the couple owned their urban residence. Alfonso Carlos perished hit by a car when on his way to Belvedergarten

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 84

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 354, 440

- ^ e.g. Puchheim was not equipped with a heating system

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 76

- ^ personal servants were Spaniards, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 139

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 76-77

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 76

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 130. It is known that the couple travelled in 1885-1886 to India, in 1888 to Armenia, in 1893 to Algeria, in 1894 to India, Nepal, Tibet, and Singapore, in 1895 to Oceania, in 1897 to Algeria, in 1898 to south Africa, i 1901 to north Africa, in 1902 to Japan, China and Russia, in 1903 to Algeria and Morocco, in 1904 to South America, in 1905 to Tunisia, in 1907-1908 to the United States, in 1909 to south America, in 1910 to north Africa, in 1911 to central Africa, Rodrigo Lucía Castejón, María de las Nieves de Braganza y Borbón, apuntes de un viaje por la Mesopotamia otomana, [in:] Isumu 20-21 (2017-2018), p. 131

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 93. During one of their Africa journeys the couple made some 35,000 kilometres, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 78-79

- ^ initially to Italy, then also to Spain

- ^ in 1921-1924 they spent winter spells at the Italian coast in Liguria, while in 1924-1931 they lived in southern Spain: Málaga (24-25), Valencia (25-26 and 26-27), Almería (27-28), Huelva (28-29), and Algeciras (29-30, 30-31). The republican coup of April 1931 surprised the coup in Algeciras; during first days afterwards they crossed Spain from the South to Catalonia

- ^ They steered clear of luxurious hotels and meticulously negotiated prices, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 410

- ^ like siblings and their consorts, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 305

- ^ during the imperial era they were even in position to offer some help in case of problems, e.g. they intervened when Dolores, daughter to Blanca de Borbón, herself daughter to Alfonso's brother Carlos, had problems with police, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 91

- ^ Villa Nieves, [in:] Grazwiki service, available here

- ^ see Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 94, 230, 444. Alfonso considered Don Jaime "jugador, especulador, vividor", who lost part of his fortune due to gambling; he was not surprised that no responsible woman of prestigious position was willing to marry Don Jaime

- ^ Alfonso Carlos was very grateful to Don Alfonso for his help when negotiating exttraterritoriality of some Austrian estates, financially helpful solution which consisted of Spanish embassy renting the Ebenzweier palace, and providing the couple with incognito diplomatic passports, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 129, 134, 164, 379

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 351, 396

- ^ especially Sixte and Xavier; this was because both brothers fought for Entente during the Great War. In the early 1920s Alfonso referred to Xavier as "un buen chico", but excessively under influence of Sixto. He refused to receive Xavier in Vienna and preferred not to correspond with him directly, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 213-214, 234. This must have changed some time until the mid-1930s, as in early 1936 Alfonso Carlos appointed Xavier his successor as the Carlist regent

- ^ Mabrouka was sort of redeemed from semi-slavery and christened as Carmen

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 497. Her later fate is unknown

- ^ Alfonso's father having abandoned his wife entered into an intimate relationship with a British commoner, and had 2 children. It is not clear whether Alfonso has ever met them. Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 494

- ^ Alfonso was born in Britain, spent his childhood in Italy, and his youth fell on residence in Czechia and Austria. His father was a native-Spanish speaker, but he abandoned the family early; his mother was not a native-Spanish speaker. Alfonso learnt Spanish during his childhood and wrote in Spanish fluently, though the quality of his spoken Spanish is not clear. It is neither clear what language he preferred to use in private, e.g. when communicating with his wife. During his entire life Alfonso spent no more than 50 months in Spain, 19 months during the 1873-1874 spell and then up to 30 months during short-term voyages in the 1920s and the 1930s

- ^ Alfonso believed that Hispanic America has a mission of opposing "la rapacidad de una raza absorbente" as part of great confrontation of races, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 77

- ^ as opposed to other nations, especially the rude French, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 371

- ^ in his private correspondence Alfonso expected that "God will punish" the Entente, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 99. Even many years later he refused to correspond with family members who fought for the Entente, e.g. in the 1920s Alfonso preferred not to speak to and not to write to his relative prince Xavier because of his wartime service in the Belgian army, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 213

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 135, 180, 198 and many more

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 118

- ^ e.g. he attributed problems of the daughter of his niece to her French governess, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 91; he claimed that France is robbing defeated Germany, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017 p. 307, and when travelling through France he referred to a nightmare in "savage country", Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 208, 369. In comparison to anti-French outlook, his anti-British sentiment was relatively moderate; he sympathised with Boers against the British, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 85

- ^ afterwards the Spanish authorities officially requested extradition of Alfonso Carlos as responsible for the crimes of "incendio, violación y asesinato", Alfonso de Borbón y de Este, [in:] Biografias y Vidas service

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 81; however, he was happy with progress of the Rif War, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 160

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 80

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 82

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 99

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 458

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 95

- ^ his wife's uncle Charles, 6th Prince of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg, was President in Germany, in Italy the League operated under the patronage of King Victor Emmanuel II and in Spain with King Alfonso XIII as Honorary President

- ^ The Effort to Abolish the Duel, [in:] The North American Review 175 (August 1902); The Fight Against Duelling in Europe, [in:] The Fortnightly Review 90 (1 August 1908); Resumé de l'histoire de la création et du développement des ligues contre le duel et pour la protection de l'honneur dans les différents pays de l'Europe de fin novembre 1900 à fin octobre 1908, Vienna 1908

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 212, 250, 281, 384, 419, 444

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 129, 134, 138, also "país de ladrones donde no se respectan ni derechos, ni propiedad, ni leyes", Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 227. Alfonso paid 4 law offices to fight off republican attempts he perceived aimed against his property and remained in constant lawsuits against provincial and municipal authorities, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 138, 420

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 322

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 432

- ^ a sad fruit of masonic French and revolutionary Russian influence, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 439

- ^ neither Mussolini nor Hitler are referred in his private corresponence

- ^ in 1849 the claim was with Alfonso's uncle, who was posing as Carlos VI. The first in line of succession was Alfonso's father, and the second in line was Alfonso's older brother. For genealogical tree see e.g. Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 44

- ^ in 1861 Carlos VI died unexpectedly, perhaps of typhus, and the claim passed to his younger brother and Alfonso's father, who posed as Juan III. The first in line of succession was Alfonso's older brother

- ^ in 1868 Juan III abdicated in favor of his son and Alfonso's older brother, who posed as Carlos VII

- ^ Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, p. 293

- ^ see e.g. El Atlántico 26.11.87, available here

- ^ Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista. Historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820, pp. 70, 178, 191, Canal 2000, p. 293

- ^ "haberse mantenido desde el final de la guerra de 1872-1876 en un segundo plano", Canal 2000, p. 292

- ^ opinion of two Carlist pundits, Manuel Polo y Peyrolón and Francisco Melgar, revealed in private correspondence in the early 1900s; "santo porque sus virtudes privadas y prácticas huelen verdaderamente a Santidad, pero imbécil porque es hombre de ningún alcance y no ha hecho ni aconsejado en toda su vida a su hermano más que necedades", referred after Javier Estevé Matí, El carlismo ante la reorganización de las derechas, [in:] Pasado y Memoria 13 (2014), p. 127

- ^ see e.g. Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, pp. 67, 71, 94, 392

- ^ compare Alfonso Carlos' correspondence in Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 413

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 444

- ^ Hervé Pinoteau, État de l'ordre du Saint-Esprit en 1830 et la survivance des ordres du roi, Paris 1983, ISBN 272330213X, p. 154

- ^ François-Marin Fleutot, Patrick Louis, Les royalistes: enquête sur les amis du roi aujourd'hui, Paris 1988, ISBN 2226035435, p. 71

- ^ it appears from his correspondence that Alfonso Carlos resided in the south of France during the winters of 1931/32, 1932/33, 1933/34 and 1935/36, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, pp. 461, 471, 472

- ^ Tradición 01.07.33, available here; some claim that the event took place in 1934, but provide no source, see e.g. Jacques Bernot, Les Princes Cachés, Paris 2015, ISBN 9782851577450, p. 173

- ^ in 1931 Alfonso Carlos wrote about "corona de espinas que cayo sobre mi cabeza" and regretted that his incognito journey and tranquility were now gone gor ever, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, pp. 460–461

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, p. 459

- ^ also in private he abandoned the name of Alfonso and since inheriting the claim he started to sign private letters as Alfonso Carlos, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, p. 65

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, p. 462

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, p. 458

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, p. 461

- ^ Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349, p. 85; some scholars claim that he was prepared to recognize the Alfonist claimant provided the latter embraces Traditionalist principles, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 86

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 87

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 110

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, pp. 474-475

- ^ Karl Pius politely approached Alfonso Carlos seeking advice on his potential own dynastic claim, at the time already advanced by a minor faction of Carlists, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 216

- ^ in the summer of 1935 Don Alfonso vivisted Puchheim to invite Alfonso Carlos and his wife to Rome, to attend the wedding of his son Don Juan. Apparently politics and dynastic questions have not been discussed. Don Alfonso seemed relieved to learn that Alfonso Carlos would not attend. Later Don Alfonso suggested he was disappointed by the meeting, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, pp. 480, 484

- ^ though already firmly leaning against any dynastic agreement with Don Alfonso, until early 1936 Alfonso Carlos did not make a final decision. In November 1935 he noted that "temo todas a Javier de Parma, a don Juan no". He also complained about being challenged by undefined "brigadistas" (cruzadistas?) from the one side, and by Don Alfonso from the other, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, p. 484

- ^ the official decree was dated 23 January 1936, but for some time it was known to the few, Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, p. 319

- ^ Alfonso Carlos was doubly related to prince Xavier. First, he was Xavier's maternal uncle, as Alfonso Carlos married the sister of Xavier's mother. Second, Alfonso Carlos was also the brother of Xavier's paternal uncle, Carlos VII (who was married to the sister of Xavier's father). In the 1920s Alfonso avoided contact with the Sixte and Xavier Borbón-Parma brothers due to their engagement in Entente troops during the First World War; details and timing of the turnaround are not clear. It is neither clear whether Alfonso initially targeted Sixte, the older of the two brothers, in his Carlist speculations; Sixte died unexpectedly in 1934

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 230

- ^ Miguéliz Valcarlos 2017, p. 439

- ^ Román Oyarzun Oyarzun, Historia del carlismo, Madrid 2008, ISBN 8497614488, p. 461

- ^ Manuel Fal became Jefe Delegado; José Luis Zamanillo became head of Requeté; José Lamamie de Clairac became head of the secretariat; Manuel Senante became editor-in-chief of El Siglo Futuro, now a semi-official Carlist daily; Domingo Tejera became editor of key Andalusian party daily La Union; a few former Integrists (Manuel Senante, Ricardo Gómez Roji, Emilio Ruiz Muñoz and Domingo Tejera) entered the newly created Council of Culture

- ^ Alfonso Carlos settled in Paris in late 1931. In the spring of 1932 he and his wife moved as a Colombian Fernández couple into a hotel in Ascain, a mountainous town in the French Pyrenees some 4 km away from the Spanish frontier. There he was put in touch with Alfonsist plotters; details are not clear; reportedly they agreed to form an interparty committee. The only tangible effect was increased volume of arms smuggling, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 89

- ^ in 1933 Alfonso Carlos was rather skeptical about a common right-wing front, but he decided to agree not to run against the call of the Pope for unity of all Catholics, Miguéliz Valcarlos 2009, pp. 474-475. In late 1934 he was still hesitant, yet eventually authorised the talks about entering the National Bloc, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 189

- ^ Alfonso Carlos first met Fal Conde in the summer of 1933 in France and from the onset was very favorably impressed, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 118

- ^ nomination to jefé delegado, traditional position held by Carlist political leaders in Spain, came in December 1935, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 215

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 200

- ^ see e.g. his letter to the pope, dated 13 April 1936 and sent from Guethary, Miguel Romero Saiz, Doña Blanca, una reina sin corona bajo el carlismo, Cuenca 2018, ISBN 9788495414786, p. 268

- ^ see e.g. Julio Aróstegui, Combatientes Requetés en la Guerra Civil Española (1936–1939), Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499709758, p. 106

- ^ Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, p. 325

- ^ Aróstegui 2013, p. 115

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 248

- ^ Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936–1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, p. 37

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 252

- ^ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 133

- ^ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 118

- ^ it was named Tercio María de las Nieves, for its wartime fate see Aróstegui 2013, pp. 403-428

- ^ Canal 2000, p. 328

- ^ Ignacio Romero Raizabal, Boinas rojas en Austria, Burgos 1936, p. 21

- ^ sequence of events referred after Prinz Alfonso Carlos von Bourbon schwer verunglückt, [in:] Neues Wiener Journal 29.09.36, available here; in this version the car is not identified, but its driver is referred to as "Taxichauffeur" Hubert Wagner. In the same daily from the following day the car was referred to as "Lohnauto", Prinz Alfonso von Bourbon gestorben, [in:] Neues Wiener Journal 30.09.36, available here. Another version is presented by one of the Carlist attendees of the funeral, who reportedly repeated the story as accounted by Alfonso Carlos' secretary: in this account it was a loaded military truck, and a soldier who was driving it did not manage to brake in time, Romero Raizabal 1936, p. 98. Also the widow when accounting the accident refers to "a camion", Romero Raizábal 1936, p. 179. This version is often repeated in literature, though at times "military truck" is replaced with "police truck"

- ^ Neues Wiener Journal 29.09.36

- ^ Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldía carlista. Memoria de una represión silenciada: Enfrentamientos, marginación y persecución durante la primera mitad del régimen franquista (1936-1955), Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711, pp. 52-53. Apart from noting temporal coincidence, not a shadow of proof has been presented

- ^ e.g. former empress Zita, prince Elias de Borbon-Parma (who officially represented the deposed Alfonso XIII), Blanca de Borbon and her son archduke Karl Pius, prince Lowenstein, prince Schwarzenberg and others, Romero Raizábal 1936, pp. 98-99; the Austrian government was reportedly represented by archduke Maximilian Eugen

- ^ the Carlist team arriving from Spain included Manuel Fal, Jose-Luis Zamanillo, José Martínez Berasáin, Ignacio Baleztena, Luis Hernando de Larramendi, Roman Oyarzun, Ignacio Romero Raizabal and 3 young requetes, related to Baleztena and Oyarzun. Among members of the top command layer it was Conde Rodezno who did not attend

- ^ upon learning the news on September 29 in Burgos, Carlist leaders waited for Fal Conde to return from Toledo, just seized by Nationalist troops. On October 1 they travelled by car to Saint-Jean-de-Luz and caught the night train to Paris, where they arrived on the following morning. In the afternoon of October 2 they took the night train from Paris via Geneva to Vienna. In Salzburg they learnt they would not make it to attend the ceremony in Vienna; hence, they left the train in Puchheim just on time when the funeral was about to begin; for detailed account see Romero Raizábal 1936

- ^ Alfonso de Borbón y de Este entry, [in:] Biografías y Vidas service, available here. In 1875 the students of Graz organised a protest demonstration in front of Alfonso's estate; reportedly his reaction was arrogant, Villa Nieves, [in:] Grazwiki service, available here

- ^ Santiago López, Los sucesos de Cuenca, ocurridos en julio de 1874, Cuenca 1878. In the book it was Maria de las Nieves presented as a diabolic woman instigating violence, who dominated Alfonso and provoked him towards atrocities

- ^ see for instance José Nakens, Los crímenes del carlismo, s.l., s.d. (1890s), Folleto 10, p. 9. (Ripoll), or Folleto 11, p. 15 (Berga, "infames asesinados diciendo que so los habian ordenado D. Alfonso y doña Blanca")

- ^ El País 30.09.00, available here

- ^ Diego Gómez Sánchez, La muerte edificada: el impulso centrífugo de los cementerios de la ciudad de Cuenca: (siglos XI-XX), Cuenca 1998, ISBN 9788489958425, p. 293

- ^ compare Paz en la Guerra: "Desde que en julio apareció la carte del joven don Carlos a su hermano Alfonso, y con él a los españoles todos, lo hacía más que comentaria en el Casino, en un círculo en que la recibían con frialidad"

- ^ compare Zalacaín el aventurero: "Algunos que habían oído hablar de un don Alfonso, hermano de don Carlos, creían que a este don Alfonso le habían hecho rey"

- ^ see e.g. B. de Artagan [Reynaldo Brea], Príncipe heróico y soldados leales, Barcelona 1912, pp. 48-54. Though Alfonso Carlos is listed in the book second, after the then claimant Don Jaime, the amount of space dedicated to Alfonso Carlos does not differ much from this dedicated to some Carlist generals, like Tristany (5 pages) or Savalls (8 pages)

- ^ for America see e.g. his pieces in The North American Review 175 (1902) or Fortnightly Review 90 (1908), for Asia see e.g. Asian Review 95 (1917)

- ^ see e.g. El Noticiero Gaditano 03.10.31, available here, or La Gaceta de Tenerife 04.10.31, available here

- ^ El Luchador 28.01.32, available here

- ^ Miguel de Unamuno, Carta abierta a Don Alfonso de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena, rey que fue de España, [in:] Ahora 19.06.34

- ^ for 1932 see Monduber 03.03.32, available here, for 1936 see Pensamiento Alaves 07.02.36, available here

- ^ José Luis Agudín Menéndez, Un rey viejo para tiempos nuevos: la construcción mediática del pretendiente Alfonso Carlos I en la prensa carlista durante la II República, [in:] Pasado y memoria: Revista de historia contemporánea 18 (2019), pp. 135–163

- ^ compare Roman Oyarzun, Historia del carlismo, Madrid 1944, especially sections titled Epilogo and Autocrítica y critica de los críticos, pp. 491–503

- ^ however, the monument honoring the 1874 victims, erected in Cuenca in 1877, was quietly demolished in 1944. Today the place is occupied by a building

- ^ Melchor Ferrer (ed.), Documentos de don Alfono Carlos de Borbón y Austria-Este, Madrid 1950

- ^ Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXX, Sevilla 1979; the volume was reportedly edited posthumously Enrique Roldán González, Cain Somé Laserna, El carlismo andaluz: estado de la cuestión, [in:] Alejandra Ibarra Aguirregabiria (ed.), No es país para jovenes, Madrid 2012, ISBN 9788498606362, p. 9

- ^ Melchor Ferrer, Don Alfonso Carlos de Borbón y Austria-Este, Sevilla 1979

- ^ e.g. Alfonso Carlos is not mentioned a single time in classic historiographic synthesis by Javier Tusell, Historia de España en el siglo XX, vol. 2, La criris de los años treinta: República y Guerra Civil, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788430606306

- ^ for comments about the impact of Alfonso Carlos' decision on regency see e.g. Blinkhorn 2008, p. 312, Oyarzun 1968, pp. 524–525, Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El Naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo 1962-1977, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 8431315644, p. 29, Jaime Ignacio del Burgo Tajadura, El agónico final del carlismo, [in:] Cuadernos de pensamiento político 31 (2011), p. 291

- ^ Cristina de la Puente, José Ramón Urquijo Goitia, El autor: Alfonso de Borbon y Austria-Este, [in:] Alfonso de Borbón Austria-Este, Viaje al Cercano Oriente en 1868: Constantinopla, Egipto, Suez, Palestina, Zaragoza 2012, ISBN 9788413403755, pp. XXXVII–LXXII

Further reading

[edit]- Maria das Neves de Borbón. Mis memorias sobre nuestra campaña en Cataluña en 1872 y 1873 y en el centro en 1874. 1a parte, de 21 abril 1872 a 31 agosto 1873 (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1934). His wife's memoirs of the Third Carlist War.

- 1849 births

- 1936 deaths

- 19th-century Spanish people

- 20th-century Spanish nobility

- People from London

- House of Bourbon (Spain)

- Spanish infantes

- Dukes of Spain

- Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain

- Legitimist pretenders to the French throne

- Spanish military personnel of the Third Carlist War (Legitimist faction)

- Carlist pretenders to the Spanish throne

- Road incident deaths in Austria

- Navarrese titular monarchs

- Spanish expatriates in Austria

- Pedestrian road incident deaths