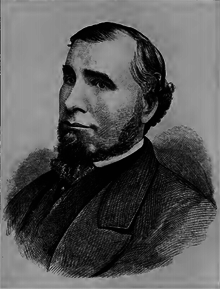

Alexander Macdonald (Lib–Lab politician)

Alexander Macdonald (27 June 1821 – 31 October 1881) was a Scottish miner, teacher, trade union leader and Lib–Lab politician.

Family and education

[edit]Macdonald was born in New Monkland, Lanarkshire, the son of Daniel McDonald and his wife Ann (née Watt). His father was an agricultural worker at that time but had formerly served in the Royal Navy and was later to work as a coal and iron miner.[1] Macdonald, who adopted the longer spelling of his name in the 1870s, had little formal education as a boy, but in his twenties he attended evening classes, learning Latin and Greek. He also managed to fund attendance at winter sessions for students at Glasgow University from work as a coal miner during the summer months.[2]

Career

[edit]At the age of eight Alexander joined his father down the mines.[3] Macdonald worked in both coal and ironstone mines for the next sixteen years. Macdonald was one of the leaders of the 1842 Lanarkshire mining strike and after its defeat he lost his job forcing him to find work in another colliery.[2] From 1849–1850 he worked as a mine manager.[4]

Macdonald's education at Glasgow enabled him to become a teacher [5] and he opened his own school in 1851.[2] However, after four years he decided to concentrate his efforts in improving the pay and conditions of mine workers. In 1855 Macdonald formed a unified Scottish coal and ironstone miners’ association [5] and the following year the organisation fought a severe cut in wages. After a three-month strike, the miners were starved back to work and had to accept the lower wages offered to them.[2] Undaunted by this failure, Macdonald continued to recruit members to his union and to try to bring together the various miners’ groups from across the country. A product of this period of his leadership was the Mines Act of 1860, which allowed for election by miners of a checkweighman at each pit to ensure fair payment of wages.[5]

Macdonald's efforts to unify the miners bore fruit in November 1863 when at a meeting in Leeds workers formed the Miners' National Association and elected Macdonald as president.[2] Macdonald was elected to the first parliamentary committee of the Trades Union Congress in 1871, and he served as chairman of the committee in 1872 and 1873. He lobbied the Liberal government over changes relating to trade union activities in the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1871, and the Mines Regulation Act of 1872. He later sat on the Royal Commission on trade unions which reported in 1875, issuing a minority report calling for wider reform of labour laws than the main report had proposed.[5]

Politics

[edit]Macdonald's campaigning led him to his later career in politics. In addition to his trade union activism, Macdonald also campaigned through journalism. He wrote many articles for the Glasgow Sentinel, a newspaper in which he invested and in which he later gained a controlling interest.[6]

In 1868, Macdonald was briefly selected to be one of the candidates to contest the parliamentary constituency of Kilmarnock Burghs. However he chose to withdraw from the race to enable another advanced Liberal candidate to have a better chance of success against the more moderate sitting Liberal MP, Edward Pleydell-Bouverie.[7]

In 1874, Macdonald was invited to stand as the Lib–Lab candidate for Stafford at the 1874 general election. Macdonald won the seat and with Thomas Burt was among the first working-class members of the House of Commons.

In Parliament Macdonald tended to concentrate on trade union matters but he was also a strong supporter of Irish Home Rule.[8] Macdonald's views had always been moderate and he chose to work for reform within the parliamentary system rather than try to change things by radical direct action. This had previously led to challenges to his leadership of the miners when in 1864 the radical journalist John Towers, and the former Chartist lawyer W. P. Roberts, withdrew from Macdonald's National Association and established the Practical Miners' Association which tried to pursue a more aggressive industrial policy. They also accused Macdonald of being politically too close to the coal owners.[5] Later, some socialists, such as Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels, criticised Macdonald for his close relationship with Benjamin Disraeli and the Conservative Party.[2] Suspicion of Macdonald's approach was also fuelled by his friendship with the Tory Lord Elcho.[6] Despite all the criticisms however, Macdonald retained the confidence of most miners throughout his life and remained president of the Miners' National Union until the time of his death.[9]

Macdonald was re-elected for Stafford in the 1880 general election.

Death

[edit]After suffering from jaundice for a few weeks[3] Macdonald died at his country home at Wellhall, near Hamilton[5] on 31 October 1881.[10] He was buried at New Monkland churchyard.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Richard Lewis, Alexander Macdonald in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; OUP 2004–09

- ^ a b c d e f "Alexander Macdonald". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b The Times, 1 November 1881 p6

- ^ Keith Laybourn, Alexander Macdonald in A T Lane, Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders; Greenwood 1995 p. 596

- ^ a b c d e f Lewis, DNB

- ^ a b Laybourn, Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders

- ^ The Times, 14 November 1868 p4

- ^ The Times, 8 February 1881 p10

- ^ The Times, 19 December 1881 p11

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ The Times, 8 November 1881 p4

External links

[edit]- Scottish miners

- British trade union leaders

- Liberal-Labour (UK) MPs

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Stafford

- Members of the Parliamentary Committee of the Trades Union Congress

- UK MPs 1874–1880

- UK MPs 1880–1885

- 1821 births

- 1881 deaths

- Scottish schoolteachers

- Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies