India (Al-Biruni)

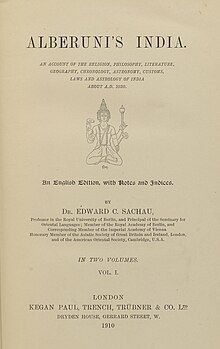

The cover of the english edition. | |

| Author | Al-Biruni |

|---|---|

| Original title | A Critical Study of Indian Doctrines, Whether Rationally Acceptable or Rejected (تحقيق ما للهند من مقولة مقبولة في العقل أو مرذولة); Kitab al-Bīrūnī fī Taḥqīq mā li-al-Hind |

| Translator | Eduard Sachau |

| Language | Arabic |

| Subject |

|

Al-Biruni's India (Arabic: تحقيق ما للهند من مقولة مقبولة في العقل أو مرذولة, romanized: Taḥqīq mā li-l-hind min maqūla maqbūla fī l-ʿaql aw mardhūla, lit. 'A Critical Study of Indian Doctrines, Whether Rationally Acceptable or Not'), also known by the shortened title Kitab al-Hind, is a book written by Persian polymath Al-Biruni about history, religions, and cultures of India.[1] It was described by the Islamic scholar Annemarie Schimmel as the first objective book on the history of religion.[1] The book was translated into German and afterward to English by Eduard Sachau.[2][3][4]

Background

[edit]Biruni's earlier contemporaries, such as Jayhani, the vizier of the Samanid Empire, had described parts of India in his book Book of Routes and Kingdoms; however Biruni considered this and other books by Arab writers marred by the authors' generally superficial knowledge about India and judgemental views on aspects of India they found or suspected to be incompatible with Islam.[5]

Biruni and his teacher Abu Nasr Mansur had studied earlier Indian texts on mathematics, such as the Sindhind, benefiting from the historical links between his childhood Khwarazm and India.[6] His book Chronology of Ancient Nations included a discussion of Indian concepts of time. After his arrival in Ghazni, he began collecting Indian books and manuscripts.[6]

In 1018, Biruni was living in Ghazni under the rule of Mahmud of Ghazni. Mahmud's father, Sabuktigin, had begun conquests in India after being given Ghazni and its surrounding areas by the Samanid Empire.[7] However, because the outskirts of Ghazni were still controlled by local Hindu princes, Sabuktigin suspended his Indian campaigns and consolidated his power and armies around Ghazni. His son Mahmud then continued his father's campaigns after assuming the throne, beginning with attacks on major population centres in Punjab and then moving to the hilltop castles of Rajasthan.[8]

Biruni was brought to the Indus Valley in 1022 as Mahmud's personal astrologer, despite his repeated ridiculing of astrologers and their fruitless efforts to predict the future, but he soon took on the role as an expert on India.[6] He was eventually able to travel independently in Sindh, including the city of Multan, where he met several major Isma'ili scholars, and parts of Punjab, including Lahore, where he studied Sanskrit. Biruni later became proficient enough in Sanskrit to translate two books from Sanskrit into Arabic, and a book from Arabic into Sanskrit.[6] By the time he returned to Ghazni in 1024, he had amassed a comprehensive library on India. In the year 1025, Mahmud laid siege against Somnath temple and the nearby fort in Gujrat; from this military success, he sent thousands of prisoners of prisoners, including Indian intellectuals, back to Ghazni.[8] These intellectuals, as well as his own library, helped Biruni develop an understanding of Indian civilization.

Content

[edit]The book begins with a critique of literature on Hindu culture available to Biruni and his contemporaries, which Biruni found both insufficient and misleading.[1] Biruni examined the religious traditions of India including Hinduism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Judaism, Christianity, the Sabeans, the Khwarazmian dynasty, Islam, and Arabian paganism, as well as the cultural practices of Hindus that would likely be unfamiliar or alien to Muslim readers, such as betel nut chewing.[9]

Biruni claimed in the opening of the book that he was interested in stating facts as presented by Hindus themselves.[1]

Says Biruni:

I shall not produce the arguments of our antagonists in order to refute such of them as I believe to be in the wrong. My book is nothing but a simple historic record of facts. I shall place before the reader the theories of the Hindus exactly as they are, and I shall mention in connection with them similar theories of the Greeks in order to show the relationship existing between them. - Volume 1, page 7 (1910 ed.)[1]

The three major areas that Biruni examined were Indian mathematics and astronomy, views on the measurement of distance and time, and the Indian understanding of geodesy.[5] The section on mathematics discussed several ways in which Indian mathematicians and astronomers were more advanced than their Central Asian and Middle Eastern contemporaries, and discussed several contributions of Indian mathematics, including the concept of zero, negative numbers, sine tables, and other innovations that were developed by the 7th century Brahmagupta.[10] Another chapter was dedicated to Indian systems of measurement. India also included new geographical information, findings in geology and paleontology, and a speculative discussion on the process by which living organisms adapt to their environment.[11]

However Biruni was sharply critical of religious and specifically Brahmin attempts to oppose new knowledge and learning by Brahmagupta and his students, but even more critical of men of learning, such as Brahmagupta, who censured themselves when confronted with charges of religious heresy. Biruni was scathing towards Brahmagupta for conceding to the religious explanation of solar eclipses (caused by the sun being swallowed by the severed head of a deity who has been punished for attempting to steal nectar).[12]

Biruni then evaluates Hindu beliefs around the Hindu pantheon including a discussion of the Vedas and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali; Biruni translated passages of the sutras from Sanskrit into Arabic and provided his own commentary.[13] Biruni compared Hindu doctrines with the beliefs of the early Greeks, as well as drawing a parallel between Hindus and Muslim Sufis.

The last seventeen chapters deal with ritual practices, mainly initiation and burial ceremonies but also mandatory sacrifices and rules of nutrition, the practice of sati, fasting, pilgrimage, and festival observance.[14]

Legacy

[edit]Kitab al-Hind continued a tradition of compiling oral sources and folk tales that dates back to Herodotus.[15] Biruni's India was a groundbreaking attempt to understand another culture both analytically, in a manner that could be verified or rejected based on available evidence, and on its own terms.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Ataman, Kemal (April 2005). "Re-reading al-birūnī's India : a case for intercultural understanding". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. 16 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1080/09596410500059623. ISSN 0959-6410.

- ^ Kūrush., Ṣafavī (2007). Introduction to Linguistics History. Pazhvāk-i Kayvān. ISBN 978-964-8727-32-6.

- ^ Kozah, Mario (20 October 2015). The Birth of Indology as an Islamic Science: Al-Bīrūnī's Treatise on Yoga Psychology. BRILL. pp. 23–31. ISBN 978-90-04-30554-0. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Sunar, Lutfi (5 May 2016). Eurocentrism at the Margins: Encounters, Critics and Going Beyond. Routledge. pp. 88, 89. ISBN 978-1-317-13996-6. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ a b Starr 2023, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Starr 2023, p. 104.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 102.

- ^ a b Starr 2023, p. 103.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 106.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 107.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 110.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 108.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 111.

- ^ Lawrence, .Bruce B (Jan 2000). ""Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān: viii. Indology". Encyclopædia Iranica. 4 (3): 285–287.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 114.

- ^ Starr 2023, p. 113.

Bibliography

[edit]- Starr, S. Frederick (2023). The Genius of their Age: Ibn Sina, Biruni, and the Lost Enlightenment (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197675557.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-767555-7.