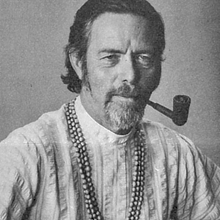

Alan Watts

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

Alan Watts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alan Wilson Watts 6 January 1915 Chislehurst, Kent, England |

| Died | 16 November 1973 (aged 58) |

| Alma mater | Seabury-Western Theological Seminary |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | |

Main interests | |

| Website | alanwatts |

| Signature | |

Alan Wilson Watts (6 January 1915 – 16 November 1973) was a British and American writer, speaker, and self-styled "philosophical entertainer",[2] known for interpreting and popularising Buddhist, Taoist, and Hindu philosophy for a Western audience.[3]

Watts gained a following while working as a volunteer programmer at the KPFA radio station in Berkeley, California. He wrote more than 25 books and articles on religion and philosophy, introducing the Beat Generation and the emerging counterculture to The Way of Zen (1957), one of the first best selling books on Buddhism. In Psychotherapy East and West (1961), he argued that psychotherapy could become the West's way of liberation if it discarded dualism, as the Eastern ways do. He considered Nature, Man and Woman (1958) to be, "from a literary point of view—the best book I have ever written".[4] He also explored human consciousness and psychedelics in works such as "The New Alchemy" (1958) and The Joyous Cosmology (1962).

His lectures found posthumous popularity through regular broadcasts on public radio, especially in California and New York, and more recently on the internet, on sites and apps such as YouTube[5] and Spotify.

Early years

[edit]Watts was born to middle-class parents in Chislehurst, Kent (now south-east London), on 6 January 1915, living at Rowan Tree Cottage, 3 (now 5) Holbrook Lane.[6] Watts's father, Laurence Wilson Watts, was a representative for the London office of the Michelin tyre company. His mother, Emily Mary Watts (née Buchan), was a housewife whose father had been a missionary. With little money, they chose to live in the countryside, and Watts, an only child, learned the names of wild flowers and butterflies.[7] Probably because of the influence of his mother's religious family[8] the Buchans, Watts became interested in spirituality. Watts was interested in storybook fables and romantic tales of the mysterious Far East.[9] He attended The King's School Canterbury where he was a contemporary and friend of Patrick Leigh Fermor.[10]

Watts later wrote of a mystical dream he experienced while ill with a fever as a child.[11] During this time he was influenced by Far Eastern landscape paintings and embroideries that had been given to his mother by missionaries returning from China. The few Chinese paintings Watts was able to see in England riveted him, and he wrote "I was aesthetically fascinated with a certain clarity, transparency, and spaciousness in Chinese and Japanese art. It seemed to float..."[12] These works of art emphasised the participatory relationship of people in nature, a theme that stood fast throughout his life and one that he often wrote about. (See, for instance, the last chapter in The Way of Zen.[13])

Buddhism

[edit]By his own assessment, Watts was imaginative, headstrong, and talkative. He was sent to boarding schools (which included both academic and religious training of the "Muscular Christian" sort) from early years. Of this religious training, he remarked "Throughout my schooling, my religious indoctrination was grim and maudlin."[14]

Watts spent several holidays in France in his teen years, accompanied by Francis Croshaw, a wealthy Epicurean with strong interests in both Buddhism and exotic, little-known aspects of European culture. Watts felt forced to decide between the Anglican Christianity he had been exposed to and the Buddhism he had read about in various libraries, including Croshaw's. He chose Buddhism, and sought membership in the London Buddhist Lodge, which was then run by the barrister and QC Christmas Humphreys (who later became a judge at the Old Bailey). Watts became the organization's secretary at 16 (1931). The young Watts explored several styles of meditation during these years.[citation needed]

Education

[edit]Watts won a scholarship to The King's School, Canterbury, the oldest boarding school in the country.[15] Though he was frequently at the top of his classes scholastically and was given responsibilities at school, he botched an opportunity for a scholarship to Trinity College, Oxford by styling a crucial examination essay in a way that he said was read as "presumptuous and capricious".[16]

When he left King's, Watts worked in a printing house and later a bank. He spent his spare time involved with the Buddhist Lodge and also under the tutelage of a "rascal guru", Dimitrije Mitrinović, who was influenced by Peter Demianovich Ouspensky, G. I. Gurdjieff, and the psychoanalytical schools of Freud, Jung and Adler. Watts also read widely in philosophy, history, psychology, psychiatry, and Eastern wisdom.

By his own reckoning, and also by that of his biographer Monica Furlong, Watts was primarily an autodidact. His involvement with the Buddhist Lodge in London gave Watts opportunities for personal growth. Through Humphreys, he contacted spiritual authors, e.g. the artist, scholar, and mystic Nicholas Roerich, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, and prominent theosophists like Alice Bailey.

In 1936, aged 21, he attended the World Congress of Faiths at the University of London, where he met the scholar of Zen Buddhism, D. T. Suzuki, who was presenting a paper.[17] Beyond attending discussions, Watts studied the available scholarly literature, learning the fundamental concepts and terminology of Indian and East Asian philosophy.

Influences and first publication

[edit]Watts's fascination with the Zen (Ch'an) tradition—beginning during the 1930s—developed because that tradition embodied the spiritual, interwoven with the practical, as exemplified in the subtitle of his Spirit of Zen: A Way of Life, Work, and Art in the Far East. "Work", "life", and "art" were not demoted due to a spiritual focus. In his writing, he referred to it as "the great Ch'an (emerging as Zen in Japan) synthesis of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism after AD 700 in China."[18] Watts published his first book, The Spirit of Zen, in 1936. Two decades later, in The Way of Zen[19] he disparaged The Spirit of Zen as a "popularisation of Suzuki's earlier works, and besides being very unscholarly it is in many respects out of date and misleading."

Watts married Eleanor Everett, whose mother Ruth Fuller Everett was involved with a traditional Zen Buddhist circle in New York. Ruth Fuller later married the Zen master (or "roshi"), Sokei-an Sasaki, who served as a sort of model and mentor to Watts, though he chose not to enter into a formal Zen training relationship with Sasaki. During these years, according to his later writings, Watts had another mystical experience while on a walk with his wife. In 1938 they left England to live in the United States. Watts became a United States citizen in 1943.[20]

Christian priest and afterwards

[edit]Watts left formal Zen training in New York because the method of the teacher did not suit him. He was not ordained as a Zen monk, but he felt a need to find a vocational outlet for his philosophical inclinations. He entered Seabury-Western Theological Seminary, an Episcopal (Anglican) school in Evanston, Illinois, where he studied Christian scriptures, theology, and church history. He attempted to work out a blend of contemporary Christian worship, mystical Christianity, and Asian philosophy. Watts was awarded a master's degree in theology for his thesis, which he published as a popular edition under the title Behold the Spirit: A Study in the Necessity of Mystical Religion.

He later published Myth & Ritual in Christianity (1953), an eisegesis of traditional Roman Catholic doctrine and ritual in Buddhist terms. Watts did not hide his dislike for religious outlooks that he decided were dour, guilt-ridden, or militantly proselytizing—no matter if they were found within Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism.[citation needed]

In early 1951, Watts moved to California, where he joined the faculty of the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco. Here he taught from 1951 to 1957 alongside Saburo Hasegawa (1906–1957), Frederic Spiegelberg, Haridas Chaudhuri, lama Tada Tōkan (1890–1967), and various visiting experts and professors. Hasegawa taught Watts about Japanese customs, arts, primitivism, and perceptions of nature. During this time he met the poet Jean Burden, with whom he had a four-year love affair.[21]

Watts credited Burden as an "important influence" in his life and gave her a dedicatory cryptograph in his book Nature, Man and Woman, mentioned in his autobiography (p. 297). Besides teaching, Watts was for several years the academy's administrator. One student of his was Eugene Rose, who later went on to become a noted Eastern Orthodox Christian hieromonk and controversial theologian within the Orthodox Church in America under the jurisdiction of ROCOR. Rose's own disciple, a fellow monastic priest published under the name Hieromonk Damascene, produced a book entitled Christ the Eternal Tao, in which the author draws parallels between the concept of the Tao in Chinese religion and the concept of the Logos in classical Greek philosophy and Eastern Christian theology.[citation needed]

Watts also studied written Chinese and practised Chinese brush calligraphy with Hasegawa as well as with Hodo Tobase, who taught at the academy. Watts became proficient in Classical Chinese. While he was noted for an interest in Zen Buddhism, his reading and discussions delved into Vedanta, "the new physics", cybernetics, semantics, process philosophy, natural history, and the anthropology of sexuality.[citation needed]

Middle years

[edit]Watts left the faculty in the mid-1950s. In 1953, he began what became a long-running weekly radio program at Pacifica Radio station KPFA in Berkeley. Like other volunteer programmers at the listener-sponsored station, Watts was not paid for his broadcasts. These weekly broadcasts continued until 1962, by which time he had attracted a "legion of regular listeners".[22][23]

Watts continued to give numerous talks and seminars, recordings of which were broadcast on KPFA and other radio stations during his life. These recordings are broadcast to this day. For example, in 1970, Watts' lectures were broadcast on Sunday mornings on San Francisco radio station KSAN;[24] and even today a number of radio stations continue to have an Alan Watts program in their weekly program schedules.[25][26][27] Original tapes of his broadcasts and talks are currently held by the Pacifica Radio Archives, based at KPFK in Los Angeles, and at the Electronic University archive founded by his son, Mark Watts.

In 1957 Watts, then 42, published one of his best-known books, The Way of Zen, which focused on philosophical explication and history. Besides drawing on the lifestyle and philosophical background of Zen in India and China and Japan, Watts introduced ideas drawn from general semantics (directly from the writings of Alfred Korzybski) and also from Norbert Wiener's early work on cybernetics, which had recently been published. Watts offered analogies from cybernetic principles possibly applicable to the Zen life. The book sold well, eventually becoming a modern classic, and helped widen his lecture circuit.

In 1958, Watts toured parts of Europe with his father, meeting the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung and the German psychotherapist Karlfried Graf Dürckheim.[28]

Upon returning to the United States, Watts recorded two seasons of a television series (1959–1960) for KQED public television in San Francisco, "Eastern Wisdom and Modern Life".[29]

In the 1960s, Watts became interested in how identifiable patterns in nature tend to repeat themselves from the smallest of scales to the most immense. This became one of his passions in his research and thought.[30]

Though never affiliated for long with any one academic institution, he was Professor of Comparative Philosophy at the American Academy of Asian Studies, had a fellowship at Harvard University (1962–1964), and was a Scholar at San Jose State University (1968).[31] He lectured college and university students as well as the general public.[32] His lectures and books gave him influence on the American intelligentsia of the 1950s–1970s, but he was often seen as an outsider in academia.[33] When questioned sharply by students during his talk at University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1970, Watts responded, as he had from the early sixties, that he was not an academic philosopher but rather "a philosophical entertainer."[citation needed]

Some of Watts's writings published in 1958 (e.g., his book Nature, Man and Woman and his essay "The New Alchemy") mentioned some of his early views on the use of psychedelic drugs for mystical insight. Watts had begun to experiment with psychedelics, initially with mescaline given to him by Oscar Janiger. He tried LSD several times in 1958, with various research teams led by Keith S. Ditman, Sterling Bunnell Jr., and Michael Agron. He also tried marijuana and concluded that it was a useful and interesting psychoactive drug that gave the impression of time slowing down. Watts's books of the '60s reveal the influence of these chemical adventures on his outlook.[34]

He later said about psychedelic drug use, "If you get the message, hang up the phone. For psychedelic drugs are simply instruments, like microscopes, telescopes, and telephones. The biologist does not sit with eye permanently glued to the microscope, he goes away and works on what he has seen."[34]

Applied Aesthetics

[edit]Watts sometimes ate with his group of neighbours in Druid Heights (near Mill Valley, California), who had set up a community, living in what has been called "shared bohemian poverty".[35] Druid Heights was founded by the writer Elsa Gidlow,[36] and Watts dedicated his book The Joyous Cosmology to the people of this neighbourhood.[37] He later dedicated his autobiography to Elsa Gidlow.

Regarding his intention for living, Watts attempted to lessen the alienation that accompanies the experience of being human that he felt plagued the modern Westerner, and to lessen the ill will that was an unintentional by-product of alienation from the natural world. He felt such teaching could improve the world, at least to a degree. He also articulated the possibilities for greater incorporation of aesthetics (for example: better architecture, more art, more fine cuisine) in American life. In his autobiography he wrote, "… cultural renewal comes about when highly differentiated cultures mix".[38]

Watts discussed the theme of maithuna or spiritual-sexual union without emission by both partners in his book, Nature, Man and Woman, in which he discusses the possibility of the practice being known to early Christians and of it being kept secretly by the Church.

Later years

[edit]In his writings of the 1950s, he conveyed his admiration for the practicality in the historical achievements of Chan (Zen) in the Far East, for it had fostered farmers, architects, builders, folk physicians, artists, and administrators among the monks who had lived in the monasteries of its lineages. In his mature work, he presents himself as "Zennist" in spirit as he wrote in his last book, Tao: The Watercourse Way. Child rearing, the arts, cuisine, education, law and freedom, architecture, sexuality, and the uses and abuses of technology were all of great interest to him.[citation needed]

Though known for his discourses on Zen, he was also influenced by ancient Hindu scriptures, especially Vedanta and Yoga, aspects of which influenced Chan and Zen. He spoke extensively about the nature of the divine reality that Man misses: how the contradiction of opposites is the method of life and the means of cosmic and human evolution, how our fundamental ignorance is rooted in the exclusive nature - the instinctive grasping at identity, mind and ego, how to come in touch with the Field of Consciousness and Light, and other cosmic principles.[39]

Watts sought to resolve his feelings of alienation from the institutions of marriage and the values of American society, as revealed in his comments on love relationships in "Divine Madness" and on perception of the organism-environment in "The Philosophy of Nature". In looking at social issues he was concerned with the necessity for international peace, for tolerance, and understanding among disparate cultures.[citation needed]

Watts also came to feel acutely conscious of a growing ecological predicament.[40] Writing, for example, in the early 1960s: "Can any melting or burning imaginable get rid of these ever-rising mountains of ruin—especially when the things we make and build are beginning to look more and more like rubbish even before they are thrown away?"[41] These concerns were later expressed in a television pilot, Conversation with Myself, made for NET (National Educational Television) filmed at Elsa Gidlow's mountain retreat in 1971 in which he noted that the single track of conscious attention was wholly inadequate for interactions with a multi-tracked world.[citation needed]

Death and legacy

[edit]

In October 1973, Watts returned from a European lecture tour to his cabin in Druid Heights, California. Friends of Watts had been concerned about him for some time over his alcoholism.[43][44] On 16 November 1973, at age 58, he died in the Mandala House in Druid Heights.[42] He was reported to have been under treatment for a heart condition.[45] Before authorities could attend, his body was removed from his home and cremated on a wood pyre at a nearby beach by Buddhist monks.[46] Mark Watts relates that Watts was cremated on Muir Beach at 8:30 am after being discovered dead at 6:00 am.[47]

His ashes were split, with half buried near his library at Druid Heights and half at the Green Gulch Monastery.[48]

His son, Mark Watts, investigated his death and found that his father had planned it meticulously:

My father died to all of us very unexpectedly, but not to himself. .... And there was a group of Yamabushi Buddhists, Ajari [real name Neville Warwick, 1932–1993, a physician also known as "Dr Ajari"] was the fellow's name who ran it, and they actually showed up and took control of the site, and got my father's body ... and there was some question as to how they had arrived there so quickly, and before anybody else, and they whisked his body off before the County opens its offices. ... But David Chadwick had come to hear this and David Chadwick is the archivist for the San Francisco Zen Center, and Suzuki and my father had been good friends, and Richard Baker, rōshi Baker, had presided over my father's funeral. So after this video interview, David said to me: "I always did think it was funny that your father came and planned his own funeral" and I said "He did what?" and he described to me the meeting of Richard Baker and my father six months before he died, where he planned his funeral, and then I realized that was exactly the same time that he changed... his Will too, so I realized that almost six months to the day before my father died, that he was planning his own passing. And so once I had that piece of the puzzle, I realized that, as I look more carefully, that my father had actually been ill for some time, and that he was aware of, very aware of, his mortality and impending problems, and who knows, he may have actually done something to hasten his death ... and he planned for it, and once I got the full picture my conclusion was that Ajari had helped him, and actually been part of the plan there. So I think it was, like many things in his life, it was well thought out, well orchestrated, and well executed.[49]

— Mark Watts, Following Alan Watts with Mark Watts

His wife, Mary Jane Watts, wrote later in a letter that Watts had said to her "The secret of life is knowing when to stop".[2]

A personal account of Watts's last years and approach to death is given by Al Chung-liang Huang in Tao: The Watercourse Way.[50]

Views

[edit]On spiritual and social identity

[edit]Regarding his ethical outlook, Watts felt that absolute morality had nothing to do with the fundamental realization of one's deep spiritual identity. He advocated social rather than personal ethics. In his writings, Watts was increasingly concerned with ethics applied to relations between humanity and the natural environment and between governments and citizens. He wrote out of an appreciation of a racially and culturally diverse social landscape.[citation needed]

He often said that he wished to act as a bridge between the ancient and the modern, between East and West, and between culture and nature.[51]

Worldview

[edit]In several of his later publications, especially Beyond Theology and The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, Watts put forward a worldview, drawing on Hinduism, Chinese philosophy, pantheism or panentheism, and modern science, in which he maintains that the whole universe consists of a cosmic Self-playing hide-and-seek (Lila); hiding from itself (Maya) by becoming all the living and non-living things in the universe and forgetting what it really is – the upshot being that we are all IT in disguise (Tat Tvam Asi). In this worldview, Watts asserts that our conception of ourselves as an "ego in a bag of skin", or "skin-encapsulated ego" is a myth; the entities we call the separate "things" are merely aspects or features of the whole.

Watts's books frequently include discussions reflecting his keen interest in patterns that occur in nature and that are repeated in various ways and at a wide range of scales – including the patterns to be discerned in the history of civilizations.[52][53]

Supporters and critics

[edit]Watts' explorations and teaching brought him into contact with many noted intellectuals, artists, and American teachers in the human potential movement. His friendship with poet Gary Snyder nurtured his sympathies with the budding environmental movement, to which Watts gave philosophical support. He also encountered Robert Anton Wilson, who credited Watts with being one of his "Light[s] along the Way" in the opening appreciation of his 1977 book Cosmic Trigger: The Final Secret of the Illuminati. Werner Erhard attended workshops given by Alan Watts and said of him, "He pointed me toward what I now call the distinction between Self and Mind. After my encounter with Alan, the context in which I was working shifted."[54]

Watts has been criticized by Buddhists such as Philip Kapleau and D. T. Suzuki for allegedly misinterpreting several key Zen Buddhist concepts. In particular, he drew criticism from Zen masters who maintain that zazen must entail a strict and specific means of sitting, as opposed to being a cultivated state of mind that is available at any moment in any situation (which traditionally might be possible by a very few after intense and dedicated effort in a formal sitting practice). Typical of these is Roshi Kapleau's claim that Watts dismissed zazen on the basis of only half a koan.[55]

In regard to the half-koan, Robert Baker Aitken reports that Suzuki told him, "I regret to say that Mr. Watts did not understand that story."[56] In his talks, Watts defined zazen practice by saying, "A cat sits until it is tired of sitting, then gets up, stretches, and walks away", and referred out of context[57] to Zen master Bankei who said: "Even when you're sitting in meditation, if there's something you've got to do, it's quite all right to get up and leave".[58]

However, Watts did have his supporters in the Zen community, including Shunryu Suzuki, the founder of the San Francisco Zen Center. As David Chadwick recounted in his biography of Suzuki, Crooked Cucumber: the Life and Zen Teaching of Shunryu Suzuki, when a student of Suzuki's disparaged Watts by saying "we used to think he was profound until we found the real thing", Suzuki fumed with a sudden intensity, saying, "You completely miss the point about Alan Watts! You should notice what he has done. He is a great bodhisattva."[59]

Watts's biographers saw him—after his stint as an Anglican priest—as representative of not so much a religion but as a lone-wolf thinker and social rascal. In David Stuart's biography, Watts is seen as an unusually gifted speaker and writer driven by his own interests, enthusiasms, and demons.[60] Elsa Gidlow, whom Watts called "sister", refused to be interviewed for the biography, but later painted a kinder picture of Watts's life in her own autobiography, Elsa, I Come with My Songs. According to critic Erik Davis, his "writings and recorded talks still shimmer with a profound and galvanizing lucidity."[61]

Unabashed, Watts was not averse to acknowledging his rascal nature, referring to himself in his autobiography In My Own Way as "a sedentary and contemplative character, an intellectual, a Brahmin, a mystic and also somewhat of a disreputable epicurean who has three wives, seven children and five grandchildren".[45]

Personal life

[edit]Watts married three times and had seven children (five daughters and two sons). He met Eleanor Everett in 1936, when her mother, Ruth Fuller Everett, brought her to London to study piano. They met at the Buddhist Lodge, were engaged the following year and married in April 1938. A daughter was born in 1938 and another in 1942. Their marriage ended in 1949, but Watts continued to correspond with his former mother-in-law.[62]

In 1950, Watts married Dorothy DeWitt. He moved to San Francisco in early 1951 to teach. They had five children. The couple separated in the early 1960s after Watts met Mary Jane Yates King (called "Jano" in his circle) while lecturing in New York.

After a divorce,[citation needed] he married King in 1964. The couple divided their time between Sausalito, California,[63] where they lived on a houseboat called the Vallejo,[64] and a secluded cabin in Druid Heights, on the southwest flank of Mount Tamalpais north of San Francisco. King died in 2015.

He also maintained relations with Jean Burden, his lover and the inspiration/editor of Nature, Man and Woman.[65]

Watts was a heavy smoker throughout his life and in his later years drank heavily.[44]

In popular culture

[edit]- His quote "We think of time as a one-way motion," from his lecture Time & The More It Changes appears at the beginning of the season 1 finale of the Loki TV show along with quotes from Neil Armstrong, Greta Thunberg, Malala Yousafzai, Nelson Mandela, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Maya Angelou[66][67]

- Several songs by the American indie rock band STRFKR sample audio from Watts' lectures[68]

- The 2013 Spike Jonze movie Her, set in the near future, includes an AI based on Watts[69]

- The voice of Alan Watts with words from "Tao of Philosophy" featured in Alexander Ekman's ballet "PLAY"[70]

- An audio clip from "Out of Your Mind: The Nature of Consciousness" is used in the Volume 3 trailer for the Netflix adult animated anthology series, Love, Death & Robots[71]

- Watts was sampled in the songs The Incredible True Story by Logic,[72] Rivers Between Us by Draconian, Overthinker and "ANGST" by INZO,[73] Forget the Money by Nick Bateman, The Parable by The Contortionist,[74] Memento Mori by Architects,[75] and Sunrise by Our Last Night.[76]

- The 2017 video game Everything contains quotes from Watts' lectures.[77] (The creator previously worked on Her, which also referenced Watts[78][69])

- Watts is sampled in Dreams, a 2019 cinema and television advertisement for the Cunard cruise line[79]

Works

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lowe, Scott (February 2019). "Alan Watts – In the Academy: Essays and Lectures ed. by Peter J. Columbus and Donadrian L. Rice (review)". Nova Religio. 22 (3): 129–130. doi:10.1525/nr.2019.22.3.129. S2CID 151087402.

- ^ a b Furlong, Monica (March 2001). Zen Effects: The Life of Alan Watts (1 ed.). SkyLight Paths. p. 150. ISBN 1893361322.

- ^ James Craig Holte The Conversion Experience in America: A 'Sourcebook on American Religious Conversion Autobiography page 199

- ^ Watts, Alan W. (1973). In My Own Way: An Autobiography 1915–1965. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 280.

- ^ Braswell, Sean (8 October 2019). "A Dead Philosopher Makes New Connections on YouTube". www.ozy.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ In a 1973 interview, reading from his own autobiography, Watts estimates his time of birth as 6.20 am

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, Part 1

- ^ Zen Effects: The Life of Alan Watts, by Monica Furlong, p. 12.

- ^ Zen Effects: The Life of Alan Watts, by Monica Furlong, p. 22

- ^ Patrick Leigh Fermor An Adventure, Artemis Cooper, John Murray 2012, page 23,

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, p. 322

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1957, Part 2, Chapter 4

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, p. 60

- ^ "The lazy mysticism of Alan Watts". Philosophy for Life. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, p. 102

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, pp. 78–82

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1947/1971 Behold the Spirit, revised edition. New York: Random House / Vintage. p. 32

- ^ Watts, Alan W., 1957, p.11

- ^ "Alan Wilson Watts". Encyclopedia of World Biography.

- ^ Hudson, Berkley (16 August 1992). "She's Well-Versed in the Art of Writing Well : Poetry: Author, editor, and teacher Jean Burden shares her lifelong obsession through invitation-only workshops in her home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ KPFA Folio, Volume 13, no. 1, 9–22 April 1962, p. 14. Retrieved at archive.org on 26 November 2014.

- ^ KPFA Folio, Volume 14, no. 1, 8–21 April 1963, p. 19. Retrieved at archive.org on 26 November 2014.

- ^ Susan Krieger, Hip Capitalism, 1979, Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, ISBN 0-8039-1263-3 pbk., p. 170.

- ^ KKUP Program Schedule Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 26 November 2014.

- ^ KPFK Program Schedule Archived 2 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 26 November 2014.

- ^ KGNU Program Schedule. Retrieved on 26 November 2014.

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, p. 321.

- ^ Alan Watts, "Eastern Wisdom and Modern Life, Season 1 (1959)" and Season 2 (1960), KQED public television series, San Francisco

- ^ Ropp, Robert S. de 1995, 2002 Warrior's Way: a Twentieth Century Odyssey. Nevada City, CA: Gateways, pp. 333–334.

- ^ "Alan Watts – Life and Works". Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "Deoxy Org: Alan Watts". Archived from the original on 19 August 2007.

- ^ Weidenbaum, Jonathan. "Complaining about Alan Watts". Archived from the original on 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b The Joyous Cosmology: Adventures in the Chemistry of Consciousness (the quote is new to the 1965/1970 edition (page 26), and not contained in the original 1962 edition of the book).

- ^ ^ Davis, Erik (May 2005). Druids and Ferries. Arthur (Brooklyn: Arthur Publishing Corp.) (16). "Druids and Ferries (Archived copy)". Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Davis, Erik (May 2005). "Druids and Ferries". Arthur (16). Brooklyn: Arthur Publishing Corp. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012.

- ^ The Joyous Cosmology, p. v

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1973, p. 247.

- ^ Alan Watts: About Hinduism, Upanishads and Vedanta | Part 1, retrieved 8 May 2021

- ^ Watts himself talking in 1970 about the ecological crisis and its spiritual background

- ^ The Joyous Cosmology, p. 63

- ^ a b "Druids and Ferries: A History of Druid Heights". Techgnosis. 21 September 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Zen Effects: The Life of Alan Watts, by Monica Furlong

- ^ a b Guy, David. "Alan Watts Reconsidered". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Alan Watts, Zen Philosopher, Writer and teacher, 58, Dies". The New York Times. 16 November 1973. Retrieved 29 August 2023 – via Religion in America (Gillian Lindt, 1977).

- ^ Tweti, Mira (22 January 2016). "The Sensualist". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Watts, Mark. "Mark Watts - An Oral History Interview Conducted by Debra Schwartz in 2018" (PDF). Mill Valley Oral History Program. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Live Fully Now: Mark Watts, interview at Druid Heights cabin by Volvo Cars (posted to YouTube on 22 February 2017)

- ^ Mill Valley Library (8 July 2021). "Following Alan Watts with Mark Watts". YouTube. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Watts, Alan (1975). Huang, Chungliang Al (ed.). TAO: The Watercourse Way (Foreword). New York: Pantheon Books. pp. vii–xiii. ISBN 0-394-73311-8.

- ^ Karam, Panos (19 September 2019). "Alan Watts' Philosophy, Biography & Key Ideas of His Teachings". Life Advancer. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ De Ropp, Robert S. 2002 Warrior's Way. Nevada City, CA: Gateways, p. 334.

- ^ Watts, Alan W. 1947/1971, pp. 25–28.

- ^ William Warren Bartley, Werner Erhard, The Transformation of a Man

- ^ Kapleau 1967, pp. 21–22

- ^ Aitken 1997, p. 30. Original Dwelling Place

- ^ Alan Watts: The Truth of the Birthless Mind, from Out of Your Mind, Session 8, Lecture 8.

- ^ Peter Haskel (ed.): Bankei Zen: Translations from The Record of Bankei. Grove Press, New York 1984. p. 59.

- ^ Chadwick, D: Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Zen Teaching of Shunryu Suzuki, Broadway Books, 2000

- ^ Stuart, David 1976 Alan Watts. Pennsylvania: Chilton.

- ^ Davis, Erik (2006). The Visionary State: A Journey through California's Spiritual Landscape. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-4835-3.

- ^ Stirling 2006, p. 27

- ^ The Book on the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are (1966)

- ^ Watts, Alan, 1973, pp. 300–304

- ^ Watts, Alan W. (1973). In My Own Way: An Autobiography 1915–1965. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 297.

- ^ "Loki finale has a Bollywood connection, Marvel leaves Indian fans excited". 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Loki: Did you notice the Bollywood connect in the finale episode?". 15 July 2021.

- ^ Mak, Sarina (10 November 2016). "STRFKR – Being No One, Going Nowhere". Radio UTD. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ a b Orr, Christopher (20 December 2013). "Why Her is the Best Film of the Year". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014.

- ^ "PLAY". HDVDARTS. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Love, Death + Robots: Volume 3, Final Trailer". YouTube. 19 May 2022.

- ^ "GENIUS - Logic The Incredible True Story".

- ^ "GENIUS - Overthinker Inzo".

- ^ "GENIUS - The Contortionist The Parable".

- ^ "GENIUS - Architects Memento Mori".

- ^ Our Last Night – Sunrise, retrieved 1 July 2023

- ^ "Everything on Steam". store.steampowered.com. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Bogost, Ian (23 March 2017). "The Video Game That Claims Everything Is Connected". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Cunard's first cinema advert invites you to forget that you were dreaming". Cunard. 13 September 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aitken, Robert. Original Dwelling Place. Counterpoint. Washington, D.C. 1997. ISBN 1-887178-41-4 (paperback)

- Charters, Ann (ed.). The Portable Beat Reader. Penguin Books. New York. 1992. ISBN 0-670-83885-3 (hardcover); ISBN 0-14-015102-8 (paperback).

- Furlong, Monica, Zen Effects: The Life of Alan Watts. Houghton Mifflin. New York. 1986 ISBN 0-395-45392-5, Skylight Paths 2001 edition of the biography, with new foreword by author: ISBN 1-893361-32-2.

- Gidlow, Elsa, Elsa: I Come with My Songs. Bootlegger Press and Druid Heights Books, San Francisco. 1986. ISBN 0-912932-12-0.

- Kapleau, Philip. Three Pillars of Zen (1967) Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5975-7.

- Stirling, Isabel. Zen Pioneer: The Life & Works of Ruth Fuller Sasaki, Shoemaker & Hoard. 2006. ISBN 978-1-59376-110-3.

- Van Morrison "Alan Watts Blues". Album: Poetic Champions Compose, 1987

- Watts, Alan, In My Own Way. New York. Random House Pantheon. 1973 ISBN 0-394-46911-9 (his autobiography).

- Rice, D. L., & Columbus, P. J. (2012). Alan Watts—here and now: Contributions to Psychology, philosophy, and religion (SUNY series in Transpersonal and humanistic psychology). State University of New York Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Clark, David K. The Pantheism of Alan Watts. Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press. 1978. ISBN 0-87784-724-X

External links

[edit]- AlanWatts.org official site run by Alan Watts's son Mark Watts through the non-profit they set up together

- Alan Watts Mountain Center north of San Francisco

- Alan Watts on Cuke.com

- 1915 births

- 1973 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century Buddhists

- 20th-century English male writers

- 20th-century English non-fiction writers

- American Buddhists

- American Buddhist spiritual teachers

- American Episcopal priests

- American male non-fiction writers

- American people of English descent

- American spiritual teachers

- American spiritual writers

- Beat Generation writers

- British scholars of Buddhism

- Buddhism in the United States

- Buddhist writers

- Converts to Buddhism from Christianity

- English Buddhists

- English Buddhist spiritual teachers

- English emigrants to the United States

- English male non-fiction writers

- English spiritual teachers

- English spiritual writers

- Harvard Fellows

- Mahayana Buddhists

- British metaphysicians

- 20th-century mystics

- Pantheists

- People educated at The King's School, Canterbury

- People from Chislehurst

- British psychedelic drug advocates

- Writers from London

- Zen in the United States

- California Institute of Integral Studies faculty

- San Jose State University faculty