Allen Toussaint

Allen Toussaint | |

|---|---|

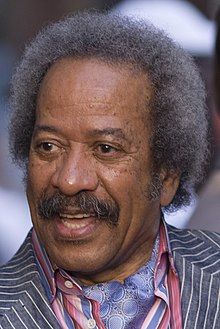

Toussaint at the Freret Street Festival, New Orleans, 2009 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Allen Richard Toussaint |

| Born | January 14, 1938 Gert Town, New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Origin | New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | November 10, 2015 (aged 77) Madrid, Spain |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1958–2015 |

| Labels | |

Allen Richard Toussaint (/ˈtuːsɑːnt/; January 14, 1938 – November 10, 2015) was an American musician, songwriter, arranger, and record producer. He was an influential figure in New Orleans rhythm and blues from the 1950s to the end of the century, described as "one of popular music's great backroom figures."[1] Many musicians recorded Toussaint's compositions. He was a producer for hundreds of recordings: the best known are "Right Place, Wrong Time", by longtime friend Dr. John, and "Lady Marmalade" by Labelle.

Biography

[edit]Early life and career

[edit]The youngest of three children, Toussaint was born in 1938 in New Orleans and grew up in a shotgun house in the Gert Town neighborhood, where his mother, Naomi Neville (whose name he later adopted pseudonymously for some of his works), welcomed and fed all manner of musicians as they practiced and recorded with her son. His father, Clarence, worked on the railway and played trumpet.[1][2] Allen Toussaint learned piano as a child and took informal music lessons from an elderly neighbor, Ernest Pinn.[3] In his teens he played in a band, the Flamingos, with the guitarist Snooks Eaglin,[4] before dropping out of school. A significant early influence on Toussaint was the syncopated "second-line" piano style of Professor Longhair.[2] Toussaint was raised Catholic.[5]

After a lucky break at age 17, in which he stood in for Huey "Piano" Smith at a performance with Earl King's band in Prichard, Alabama,[6] Toussaint was introduced to a group of local musicians led by Dave Bartholomew, who performed regularly at the Dew Drop Inn, a nightclub on Lasalle Street in Uptown New Orleans.[7] His first recording was in 1957 as a stand-in for Fats Domino on Domino's record "I Want You to Know", on which Toussaint played piano and Domino overdubbed his vocals.[3] His first success as a producer came in 1957 with Lee Allen's "Walking with Mr. Lee".[1] He began performing regularly in Bartholomew's band, and he recorded with Fats Domino, Smiley Lewis, Lee Allen and other leading New Orleans performers.[4]

After being spotted as a sideman by the A&R man Danny Kessler, he initially recorded for RCA Records as Al Tousan. In early 1958 he recorded an album of instrumentals, The Wild Sound of New Orleans, with a band including Alvin "Red" Tyler (baritone sax), either Nat Perrilliat or Lee Allen (tenor sax), either Justin Adams or Roy Montrell (guitar), Frank Fields (bass), and Charles "Hungry" Williams (drums).[8] The recordings included Toussaint and Tyler's composition "Java", which first charted for Floyd Cramer in 1962 and became a number 4 pop hit for Al Hirt (also on RCA) in 1964.[9] Toussaint recorded and co-wrote songs with Allen Orange in the early 1960s.[10]

Success in the 1960s

[edit]Minit and Instant Records

[edit]In 1960, Joe Banashak, of Minit Records and later Instant Records, hired Toussaint as an A&R man and record producer.[3][11] He did freelance work for other labels, such as Fury. Toussaint played piano, wrote, arranged and produced a string of hits in the early and mid-1960s for New Orleans R&B artists such as Ernie K-Doe, Chris Kenner, Irma Thomas (including "It's Raining"), Art and Aaron Neville, The Showmen, and Lee Dorsey, whose first hit "Ya Ya" he produced in 1961.[1][4]

The early to mid-1960s are regarded as Toussaint's most creatively successful period.[3] Notable examples of his work are Jessie Hill's "Ooh Poo Pah Doo" (written by Hill and arranged and produced by Toussaint), Ernie K-Doe's "Mother-in-Law", and Chris Kenner's "I Like It Like That".[11][12][13] A two-sided 1962 hit by Benny Spellman comprised "Lipstick Traces (on a Cigarette)" (covered by The O'Jays, Ringo Starr, and Alex Chilton) and the simple but effective "Fortune Teller" (covered by various 1960s rock groups, including The Rolling Stones, The Nashville Teens, The Who, The Hollies, The Throb, and The Searchers founder Tony Jackson).[11][14][15] "Ruler of My Heart", written under his pseudonym Naomi Neville, first recorded by Irma Thomas for the Minit label in 1963, was adapted by Otis Redding under the title "Pain in My Heart" later that year, prompting Toussaint to file a lawsuit against Redding and his record company, Stax (the claim was settled out of court, with Stax agreeing to credit Naomi Neville as the songwriter).[16] Redding's version of the song was also recorded by The Rolling Stones on their second album and was in the Grateful Dead's early repertoire.[17] In 1964, "A Certain Girl" (originally by Ernie K-Doe) was the B-side of the first single release by The Yardbirds. The song was released again in 1980 by Warren Zevon, as the single from the album Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School; it reached 57 on Billboard's Hot 100. Mary Weiss, former lead singer of The Shangri-Las, released it as "A Certain Guy" in 2007.[18] Linda Ronstadt released a jazzy version of "Ruler of my Heart" in 1998 on We Ran.

Toussaint credited about twenty songs to his parents, Clarence and Naomi, sometimes using the pseudonym "Naomi Neville".[19][20] These include "Fortune Teller", first recorded by Benny Spellman in 1961, "Pain In My Heart," first a hit for Otis Redding in 1963, and "Work, Work, Work", recorded by The Artwoods in 1966. Alison Krauss and Robert Plant covered "Fortune Teller" on their 2007 album Raising Sand.[21]

Sansu: Soul and early New Orleans funk

[edit]Toussaint was drafted into the United States Army in 1963 but continued to record when on leave.[1] After his discharge in 1965, he joined forces with Marshall Sehorn[22] to form Sansu Enterprises, which included a record label, Sansu, variously known as Tou-Sea, Deesu, or Kansu, and recorded Lee Dorsey, Chris Kenner, Betty Harris, and others. Dorsey had hits with several of Toussaint's songs, including "Ride Your Pony" (1965), "Working in the Coal Mine" (1966), and "Holy Cow" (1966).[4][22] The core players of the rhythm section used on many of the Sansu recordings from the mid- to late 1960s, Art Neville and the Sounds, consisted of Art Neville on keyboards, Leo Nocentelli on guitar, George Porter Jr on bass, and Zigaboo Modeliste on drums. They later became known as The Meters.[23] Their backing can be heard in songs such as Dorsey's "Ride Your Pony" and "Working in the Coal Mine", sometimes augmented by horns, which were usually arranged by Toussaint.[24] The Toussaint-produced records of these years backed by the members of the Meters, with their increasing use of syncopation and electric instrumentation, built on the influences of Professor Longhair and others before them, but updated these strands, effectively paving the way for the development of a modern New Orleans funk sound. [23][25]

1970s to 1990s

[edit]Toussaint continued to produce The Meters when they began releasing records under their own name in 1969. As part of a process begun at Sansu and reaching fruition in the 1970s, he developed a funkier sound, writing and producing for a host of artists, such as Dr. John (backed by the Meters, on the 1973 album In the Right Place, which contained the hit "Right Place, Wrong Time") and an album by The Wild Tchoupitoulas, a New Orleans Mardi Gras Indians tribe led by "Big Chief Jolly" (George Landry) (backed by the Meters and several of his nephews, including Art and Cyril Neville of the Meters and their brothers Charles and Aaron, who later performed and recorded as The Neville Brothers).[26][27][28]

In the 1970s, Toussaint began to work with artists from beyond New Orleans artists, such as B. J. Thomas, Robert Palmer, Willy DeVille, Sandy Denny, Elkie Brooks, Solomon Burke, Scottish soul singer Frankie Miller (High Life), and southern rocker Mylon LeFevre.[29][30] He arranged horn music for The Band's albums Cahoots (1971) and Rock of Ages (1972), as well as for the documentary film The Last Waltz (1978).[31][32][33] Boz Scaggs recorded Toussaint's "What Do You Want the Girl to Do?" on his 1976 album Silk Degrees, which reached number 2 on the U.S. pop albums chart. The song was also recorded by Bonnie Raitt for her 1975 album Home Plate and by Geoff Muldaur (1976), Lowell George (1979), Vince Gill (1993), and Elvis Costello (2005).[34] In 1976 he collaborated with John Mayall on the album Notice to Appear.[35]

In 1973 Toussaint and Sehorn created the Sea-Saint recording studio in the Gentilly section of eastern New Orleans.[36][37] Toussaint began recording under his own name, contributing vocals as well as piano. His solo career peaked in the mid-1970s with the albums From a Whisper to a Scream and Southern Nights.[38][39] During this time he teamed with Labelle and produced their acclaimed 1975 album Nightbirds, which contained the number one hit "Lady Marmalade". The same year, Toussaint collaborated with Paul McCartney and Wings for their hit album Venus and Mars and played on the song "Rock Show". In 1973, his "Yes We Can Can" was covered by The Pointer Sisters for their self-titled debut album; released as a single, it became both a pop and R&B hit and served as the group's introduction to popular culture. Two years later, Glen Campbell covered Toussaint's "Southern Nights" and carried the song to number one on the pop, country, and adult contemporary charts.[40] Toussaint's song "I'll Take A Melody" figured permanently in the repertoire of the Jerry Garcia Band.

In 1987, he was the musical director of an off-Broadway show, Staggerlee, with a score composed of songs from his catalog, which ran for 150 performances.[3][41] Like many of his contemporaries, Toussaint found that interest in his compositions was rekindled when his work began to be sampled by hip hop artists in the 1980s and 1990s.[42][43]

2000s

[edit]

Most of Toussaint's possessions, including his home and recording studio, Sea-Saint Studios, were lost during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[44][45] He initially sought shelter at the Astor Crowne Plaza Hotel on Canal Street.[44] Following the hurricane, whose aftermath left most of the city flooded, he left New Orleans for Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and for several years settled in New York City.[44][45] His first television appearance after the hurricane was on the September 7, 2005, episode of the Late Show with David Letterman, sitting in with Paul Shaffer and his CBS Orchestra. Toussaint performed regularly at Joe's Pub in New York City through 2009.[46] He eventually returned to New Orleans and lived there for the rest of his life.[47]

Toussaint is interviewed on screen, served as a musical director, led his band and appears in performance footage in the 2005 documentary film Make It Funky!, which presents a history of New Orleans music and its influence on rhythm and blues, rock and roll, funk and jazz.[48] In the film, he performed a medley of his compositions "Fortune Teller", "Working in the Coal Mine" and "A Certain Girl". He also performed "Tipitina" in a piano duo with Jon Cleary, and accompanied Irma Thomas on "Old Records", Lloyd Price on "Lawdy Miss Clawdy", and Bonnie Raitt on "What is Success".[49]

The River in Reverse, Toussaint's collaborative album with Elvis Costello, was released on May 29, 2006, in the UK on Verve Records by Universal Classics and Jazz UCJ.[50] It was recorded in Hollywood and at the Piety Street Studio in the Bywater, as the first major studio session to take place after Hurricane Katrina.[51] In 2007, Toussaint performed a duet with Paul McCartney of a song by New Orleans musician and resident Fats Domino, "I Want to Walk You Home", as their contribution to Goin' Home: A Tribute to Fats Domino on Vanguard.[52]

In 2008, Toussaint's song "Sweet Touch of Love" was used in a deodorant commercial for the Axe (Lynx) brand. The commercial won a Gold Lion at the 2008 Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival. In February 2008, Toussaint appeared on Le Show, the Harry Shearer show broadcast on KCRW. He appeared in London in August 2008, where he performed at the Roundhouse.[53] In October 2008 he performed at Festival New Orleans at The O2 alongside acts such as Dr. John and Buckwheat Zydeco.[54] Sponsored by Quint Davis of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and Philip Anschutz, the event was intended to promote New Orleans music and culture and to revive the once lucrative tourist trade that had been almost completely lost following the flooding that came with Hurricane Katrina.[54] After his second performance at the festival, Toussaint appeared alongside Louisiana Lieutenant Governor Mitch Landrieu.[55]

Toussaint performed instrumentals from his album The Bright Mississippi and many of his older songs for a taping of the PBS series Austin City Limits, which aired on January 9, 2015.[56][57] In December 2009, he was featured on Elvis Costello's Spectacle program on the Sundance Channel,[58] singing "A Certain Girl".[59] Toussaint appeared on Eric Clapton's 2010 album, Clapton, in two Fats Waller covers, "My Very Good Friend the Milkman" and "When Somebody Thinks You're Wonderful".[60]

His late-blooming career as a performer began when he accepted an offer to play a regular Sunday brunch session at an East Village pub. Interviewed in 2014 by The Guardian′s Richard Williams, Toussaint said, "I never thought of myself as a performer.... My comfort zone is behind the scenes." In 2013 he collaborated on a ballet with the choreographer Twyla Tharp.[1] Toussaint was a musical mentor to Swedish-born New Orleans songwriter and performer Theresa Andersson.[61] Toussaint's two marriages ended in divorce.[2]

Death

[edit]Toussaint died in the early hours of November 10, 2015, in Madrid, Spain, while on tour. Following a concert at the Teatro Lara on Calle Corredera Baja de San Pablo, he had a heart attack at his hotel and was pronounced dead on his arrival at the hospital.[62] He was 77. He had been due to perform a sold-out concert at the EFG London Jazz Festival at The Barbican on November 15 with his band and Theo Croker. He was also scheduled to play with Paul Simon at a benefit concert in New Orleans on December 8.[2] His final recording, American Tunes, titled after the Paul Simon song, which he sings on the album, was released by Nonesuch Records on June 10, 2016.[63]

He was survived by his three children, Clarence (better known as Reginald), Naomi, and Alison, and several grandchildren. His children had managed his career in his last years.[64][47]

Writing in The New York Times, Ben Sisario quoted Quint Davis, producer of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival: "In the pantheon of New Orleans music people, from Jelly Roll Morton to Mahalia Jackson to Fats—that's the place where Allen Toussaint is..." Paul Simon said, "We were friends and colleagues for almost 40 years.... We played together at the New Orleans jazz festival. We played the benefits for Katrina relief. We were about to perform together on December 8. I was just beginning to think about it; now I'll have to think about his memorial. I am so sad."[47]

The Daily Telegraph described Toussaint as "a master of New Orleans soul and R&B, and one of America's most successful songwriters and producers," adding that "self-effacing Toussaint played a crucial role in countless classic songs popularised by other artists." He had written so many songs, over more than five decades, that he admitted to forgetting quite a few.[2]

Partial discography

[edit]- The Wild Sound of New Orleans (1958)

- Toussaint (1971, a.k.a. From a Whisper to a Scream)

- Life, Love and Faith (1972)

- Southern Nights (1975)

- Motion (1978)

- I Love a Carnival Ball, Mr Mardi Gras Starring Allen Toussaint (1987)

- Connected (1996)

- A New Orleans Christmas (1997)

- Allen Toussaint's Jazzity Project: Going Places (2004)

- The Bright Mississippi (2009)

- American Tunes (2016)

Awards and honors

[edit]

Toussaint was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998, the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame in 2009, the Songwriter's Hall of Fame, and the Blues Hall of Fame in 2011. In 2013 he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama.[65] In 2016, he posthumously won the Pinetop Perkins Piano Player title at the Blues Music Awards.[66] In January 2022, the New Orleans City Council voted unanimously to rename one of the city's thoroughfares, Robert E. Lee Boulevard, to Allen Toussaint Boulevard in his honor.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Williams, Richard (November 11, 2015). "Allen Toussaint obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Allen Toussaint, Songwriter: Obituary". November 12, 2015. The Telegraph. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Lichtenstein, Grace; Dankner, Laura (1993). Musical Gumbo: The Music of New Orleans. W. W. Norton. pp. 110–122.

- ^ a b c d Steve Huey, Steve. "Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ "Allen Toussaint 1938-2015". thebluemoment.com. November 10, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ "Allen Toussaint Profile". NYNO Records. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ Fensterstock, Alison. "On Top of the Charts: Allen Toussaint Is As Sharp and Prolific As Ever". Gambit Weekly (New Orleans), May 1, 2007, p. 23. Archives online at Bestofneworleans.com.

- ^ Planer, Lindsay. "Review of The Wild Sound of New Orleans". AllMusic. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1996). Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles. Menomonee Falls, WIsconsin.: Record Research. ISBN 0-89820-104-7.

- ^ "Allen Orange". SoulfulKindaMusic. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ a b c "Allen Toussaint Biography". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Biography". All Media Network. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ "Chris Kenner Billboard Singles". Allmusic. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Hamilton, Andrew. "The O'Jays, Lipstick Traces (on a Cigarette): Song Review". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Marks, Ian D.; McIntyre, Iain (2010). Wild About You: The Sixties Beat Explosion in Australia. Portland, London, Melbourne: Verse Chorus Press. pp. 49, 51–52, 54. ISBN 978-1-891241-28-4.

- ^ Bowman, Rob. (1997). Soulsville U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records. New York, Schirmer Trade Books. p. 46, note 16.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Irma Thomas, Ruler of My Heart: Song Review". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen. "Allen Toussaint, Finger Poppin' and Stompin' Feet: 20 Classic Allen Toussaint Productions for Minit...: Review". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ "Artist page for Naomi Neville on uk-charts.com". uk-charts.com. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ "Artist page for Clarence Toussaint on uk-charts.com". uk-charts.com. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ "Songs Written by Allen Toussaint". MusicVF.com. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ a b Ankeny, Jason. "Marshall Sehorn". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Meter Men Featuring Ivan Neville". Tulane University. New Orleans. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ "The Meters". Encyclopedia.com. Cengage Learning. 2004. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Stewart, Alexander (2000). "Funky Drummer: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music." Popular Music, v. 19, no. 3 (Oct. 2000), p. 297, quoting Dr. John quoted describing Professor Longhair's influence on New Orleans funk.

- ^ Chrispell, James. "In the Right Place". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Christgau, Robert. "The Wild Tchoupitoulas". Robert Christgau. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ "The Neveille Brothers". Patterson & Associates. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Anonymous (May 25, 2006). "Home of the Groove: Touched by Toussaint". Homeofthegroove.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Zell Miller (1996). They Heard Georgia Singing. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865545045. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "The Band--Cahoots: Review". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "The Band--Moondog Matinee: Review". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Deming, Mark. "The Band, The Last Waltz: Review". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ "What Do You Want the Girl To Do? - The Elvis Costello Wiki". Elviscostello.info. December 6, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Notice to Appear - John Mayall |". AllMusic. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ Alison Fensterstock, op. cit.

- ^ Jaffe, Ben, Allen Toussaint profile Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, preshallben.tumblr.com, October 2, 2014.

- ^ Planer, Lindsay. "From a Whisper to a Scream: Review". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen. "Allen Toussaint--Southern Nights: Review". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Ed Hogan. "Southern Nights, Glen Campbell | Song Info". AllMusic. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Milward, John (April 11, 1987). "Bringing A New Orleans Legend To Life An Off-broadway Musical Distills The Essential Staggerlee". Philly.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ Stephen G. Gordon (April 1, 2013). Jay-Z: CEO of Hip-Hop. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 34. ISBN 9781467708111. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Brian Coleman (2009). Check the Technique: Liner Notes for Hip-Hop Junkies. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307494429. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c Baer, April (June 24, 2015). "An Artist's Renaissance Post Hurricane Katrina". OPB. Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Santana, Rebecca; Plaisance, Stacey (November 11, 2015). "Legendary New Orleans Musician Allen Toussaint Dead At 77". TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Huffington Post. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Ashley Kahn. "Songbook liner notes". Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c Sisario, Ben (November 10, 2015). "Allen Toussaint, New Orleans R&B Mainstay, Dies at 77". New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ "IAJE What's Going On". Jazz Education Journal. 37 (5). Manhattan, Kansas: International Association of Jazz Educators: 87. April 2005. ISSN 1540-2886. ProQuest 1370090.

- ^ Make It Funky! (DVD). Culver City, California: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. 2005. ISBN 9781404991583. OCLC 61207781. 11952.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen. "Elvis Costello / Allen Toussaint, The River in Reverse: Review". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ "Elvis Costello & Allen Toussaint, The River in Reverse, Interview CD". Discogs. Discogs®. May 2006. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ "Fats Domino 'Alive and Kicking'". CBS News. February 25, 2006. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "Allen Toussaint, Roundhouse, London | Reviews | Culture". The Independent. Archived from the original on September 4, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Massarik, Jack (October 27, 2008). "The Saints Come Marching in at O2 jazz festival". Evening Standard.

- ^ Yuan, Jada (August 25, 2008). "Denver Dispatch: Kathleen Sebelius Tears Up Dance Floor at Wild Party". New York Magazine. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "Saturday's Highlights". Los Angeles Times. January 9, 2010. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Ayers, Michael D. (September 24, 2009). "Dave Matthews, Pearl Jam Set For Austin City Limits' 35th Season". Billboard. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Goldstein, Stan (September 26, 2009). "Bruce Springsteen appears with Elvis Costello at Spectacle taping". NJ.com. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "Levon Helm, Nick Lowe, Richard Thompson and Allen Toussaint". Spectacle: Elvis Costello With... Season 2. Episode 3. December 23, 2009. Sundance Channel.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (August 18, 2010). "Eric Clapton Announces New Solo Album, Clapton". Billboard. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Spera, Keith (May 1, 2012). "Letting life flow in: Songwriter Theresa Andersson's expanding roles with music and motherhood lead her to a better place". Times-Picayune. No. Saint Tammany Edition. pp. C1-2. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ "Muere el músico Allen Toussaint en Madrid tras actuar en el Teatro Lara". El Mundo (in Spanish). November 10, 2015.

- ^ "Nonesuch Releases "American Tunes," Final Recording from Late New Orleans Legend Allen Toussaint, on June 10". Nonesuch Records website. April 13, 2016.

- ^ Dominic Massa, "Influential songwriter, producer Allen Toussaint has died" Archived November 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, WWL-TV, November 10, 2015.

- ^ "National Medal of Arts | NEA". Arts.gov. February 27, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "2016 Blues Music Awards Winner List". Blues411.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ Sledge, Matt (January 6, 2022). "Allen Toussaint, New Orleans music icon, gets a boulevard renamed in his honor". nola.com. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Allen Toussaint at IMDb

- Allen Toussaint profile, NPR.org; accessed October 5, 2014.

- Allen Toussaint profile, allmusic.com; accessed October 5, 2014.

- Allen Toussaint NYNO Records profile, nynorecords.com; accessed October 5, 2014.

- Allen Toussaint speaks about songwriting and creating music NAMM Oral History Interview (2015)

- A Conversation with Allen Toussaint (interviewer: Larry Appelbaum), November 1, 2007; from The Library of Congress (Video, Captions, Transcript)

- 1938 births

- 2015 deaths

- Rhythm and blues musicians from New Orleans

- African-American pianists

- American people of French descent

- American jazz pianists

- Record producers from Louisiana

- American soul musicians

- Bell Records artists

- Nonesuch Records artists

- Reprise Records artists

- Seville Records artists

- Songwriters from Louisiana

- American rhythm and blues keyboardists

- American blues pianists

- American male jazz pianists

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- 20th-century American pianists

- 21st-century American pianists

- Jazz musicians from New Orleans

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 21st-century American male musicians

- African-American songwriters

- 20th-century African-American musicians

- 21st-century African-American musicians

- American male songwriters

- 20th-century Jazz musicians from New Orleans

- 21st-century Jazz musicians from New Orleans