History of Kashmir

| History of Kashmir |

|---|

|

The history of Kashmir is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent in South Asia with influences from the surrounding regions of Central, and East Asia. Historically, Kashmir referred to only the Kashmir Valley of the western Himalayas.[1] Today, it denotes a larger area that includes the Indian-administered union territories of Jammu and Kashmir (which consists of Jammu and the Kashmir Valley), Ladakh, the Pakistan-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, and the Chinese-administered regions of Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract.

In the first half of the 1st millennium, the Kashmir region became an important centre of Hinduism and later—under the Mauryas and Kushanas—of Buddhism. Later in the ninth century, during the rule of the Karkota Dynasty, a native tradition of Shaivism arose. It flourished in the seven centuries of Hindu rule, continuing under the Utpala and the Lohara dynasties, ending in mid-14th century.

The spread of Islam in Kashmir began during the 13th century, accelerated under Muslim rule during the 14th and 15th centuries, and led to the eventual decline of Kashmiri Shaivism in the region.

In 1339, Shah Mir became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir, inaugurating the Shah Mir dynasty. For the next five centuries, Muslim monarchs ruled Kashmir, including the Mughal Empire, who ruled from 1586 until 1751, and the Afghan Durrani Empire, which ruled from 1747 until 1819. That year, the Sikhs, under Ranjit Singh, annexed Kashmir. In 1846, after the Sikh defeat in the First Anglo-Sikh War, the Treaty of Lahore was signed and upon the purchase of the region from the British under the Treaty of Amritsar, the Raja of Jammu, Gulab Singh, became the new ruler of Kashmir. The rule of his descendants, under the paramountcy (or tutelage) of the British Crown, lasted until 1947, when the former princely state became a disputed territory, now administered by three countries: India, Pakistan, and the People's Republic of China.

Etymology

According to folk etymology, the name "Kashmir" means "desiccated land" (from the Sanskrit: ka = water and shimīra = desiccate).[2] In the Rajatarangini, a history of Kashmir written by Kalhana in the mid-12th century, it is stated that the valley of Kashmir was formerly a lake. According to Hindu mythology, the lake was drained by the great rishi or sage, Kashyapa, son of Marichi, son of Brahma, by cutting the gap in the hills at Baramulla (Varaha-mula). When Kashmir had been drained, Kashyapa asked Brahmins to settle there. This is still the local tradition, and in the existing physical condition of the country, there is some ground for the story which has taken this form. The name of Kashyapa is by history and tradition connected with the draining of the lake, and the chief town or collection of dwellings in the valley was called Kashyapa-pura, which has been identified with Kaspapyros of Hecataeus (apud Stephanus of Byzantium) and Kaspatyros of Herodotus (3.102, 4.44).[3][4] Kashmir is also believed to be the country meant by Ptolemy's Kaspeiria.[5] Cashmere is an archaic spelling of Kashmir, and in some countries it is still spelled this way.[citation needed]

Historiography

Nilamata Purana (complied c. 500–600 CE)[6] contains accounts of Kashmir's early history. However, being a Puranic source, it has been argued that it suffers from a degree of inconsistency and unreliability.[7][a] Kalhana's Rajatarangini (River of Kings), all the 8000 Sanskrit verses of which were completed by 1150 CE, chronicles the history of Kashmir's dynasties from earlier times to the 12th century.[8][9] It relies upon traditional sources like Nilmata Purana, inscriptions, coins, monuments, and Kalhana's personal observations borne out of political experiences of his family.[10][8] Towards the end of the work mythical explanations give way to rational and critical analyses of dramatic events between 11th and 12th centuries, for which Kalhana is often credited as "India's first historian".[7][8]

During the reign of Muslim kings in Kashmir, three supplements to Rajatarangini were written by Jonaraja (1411–1463 CE), Srivara, and Prajyabhatta and Suka, which end with Akbar's conquest of Kashmir in 1586 CE.[11] The text was translated into Persian by Muslim scholars such as Nizam Uddin, Farishta, and Abul Fazl.[12] Baharistan-i-Shahi and Haidar Mailk's Tarikh-i-Kashmir (completed in 1621 CE) are the most important texts on the history of Kashmir during the Sultanate period. Both the texts were written in Persian and used Rajatarangini and Persian histories as their sources.[13]

Palaeolithic

At the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic Galander site near Pampore in the Kashmir Valley, remains of the extinct elephant species Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus have been found associated with knapped stone tools produced by archaic humans, with the bones of the elephant suggested to display deliberate fracturing, perhaps produced during the act of butchery.[14] The stone tools exhibit production techniques reminiscent of the Levallois type, and the site is suggested to date to the Middle Pleistocene, around 400-300,000 years ago.[15]

Early history

The earliest Neolithic sites in the flood plains of Kashmir Valley are dated to c. 3000 BCE. Most important of these sites are the settlements at Burzahom, which had two Neolithic and one Megalithic phases. First phase (c. 2920 BCE) at Burzahom is marked by mud plastered pit dwellings, coarse pottery and stone tools. In the second phase, which lasted until c. 1700 BCE, houses were constructed on ground level and the dead were buried, sometimes with domesticated and wild animals. Hunting and fishing were the primary modes of subsistence though evidence of cultivation of wheat, barley, and lentils has also been found in both the phases.[16][17] In the megalithic phase, massive circles were constructed and grey or black burnish replaced coarse red ware in pottery.[18] During the later Vedic period, as kingdoms of the Vedic tribes expanded, the Uttara–Kurus settled in Kashmir.[19][20]

In 326 BCE, Porus asked Abisares, the king of Kashmir,[b] to aid him against Alexander the Great in the Battle of Hydaspes. After Porus lost the battle, Abhisares submitted to Alexander by sending him treasure and elephants.[22][23]

During the reign of Ashoka (304–232 BCE), Kashmir became a part of the Maurya Empire and Buddhism was introduced in Kashmir. During this period, many stupas, some shrines dedicated to Shiva, and the city of Srinagari (Srinagar) were built.[24] Kanishka (127–151 CE), an emperor of the Kushan dynasty, conquered Kashmir and established the new city of Kanishkapur.[25] Buddhist tradition holds that Kanishka held the Fourth Buddhist council in Kashmir, in which celebrated scholars such as Ashvagosha, Nagarjuna and Vasumitra took part.[26] By the fourth century, Kashmir became a seat of learning for both Buddhism and Hinduism. Kashmiri Buddhist missionaries helped spread Buddhism to Tibet and China and from the fifth century CE, pilgrims from these countries started visiting Kashmir.[27] Kumārajīva (343–413 CE) was among the renowned Kashmiri scholars who traveled to China. He influenced the Chinese emperor Yao Xing and spearheaded translation of many Sanskrit works into Chinese at the Chang'an monastery.[28]

The Alchon Huns under Toramana crossed over the Hindu Kush mountains and conquered large parts of western India including Kashmir.[29] His son Mihirakula (c. 502–530 CE) led a military campaign to conquer all of North India. He was opposed by Baladitya in Magadha and eventually defeated by Yasodharman in Malwa. After the defeat, Mihirakula returned to Kashmir where he led a coup on the king. He then conquered of Gandhara where he committed many atrocities on Buddhists and destroyed their shrines. Influence of the Huns faded after Mihirakula's death.[30][31]

In 659, Sogdia, Ferghana, Tashkent, Bukhara, Samarkand, Balkh, Herat, Kashmir, the Pamirs, Tokharistan, and Kabul all submitted to the protectorate under Emperor Gaozong of Tang.[32][33][34][35][36]

Hindu Dynasties

A succession of Hindu dynasties ruled over the region from the 7th-14th centuries.[37] After the seventh century, significant developments took place in Kashmiri Hinduism. In the centuries that followed, Kashmir produced many poets, philosophers, and artists who contributed to Sanskrit literature and Hindu religion.[38] Among notable scholars of this period was Vasugupta (c. 875–925 CE) who wrote the Shiva Sutras which laid the foundation for a monistic Shaiva system called Kashmir Shaivism. Dualistic interpretation of Shaiva scripture was defeated by Abhinavagupta (c. 975–1025 CE) who wrote many philosophical works on Kashmir Shaivism.[39] Kashmir Shaivism was adopted by the common masses of Kashmir and strongly influenced Shaivism in Southern India.[40]

In the eighth century, the Karkota Empire established themselves as rulers of Kashmir.[41] Kashmir grew as an imperial power under the Karkotas. Chandrapida of this dynasty was recognized by an imperial order of the Chinese emperor as the king of Kashmir. His successor Lalitaditya Muktapida lead a successful military campaign against the Tibetans. He then defeated Yashovarman of Kanyakubja and subsequently conquered eastern kingdoms of Magadha, Kamarupa, Gauda, and Kalinga. Lalitaditya extended his influence of Malwa and Gujarat and defeated Arabs at Sindh.[42][43] After his demise, Kashmir's influence over other kingdoms declined and the dynasty ended in c. 855–856 CE.[41]

The Utpala dynasty founded by Avantivarman followed the Karkotas. His successor Shankaravarman (885–902 CE) led a successful military campaign against Gurjaras in Punjab.[44][41] Political instability in the 10th century made the royal body guards (Tantrins) very powerful in Kashmir. Under the Tantrins, civil administration collapsed and chaos reigned in Kashmir until they were defeated by Chakravarman.[45] Queen Didda, who descended from the Hindu Shahis of Udabhandapura on her mother's side, took over as the ruler in second half of the 10th century.[41] After her death in 1003 CE, the throne passed to the Lohara dynasty.[46] Suhadeva, last king of the Lohara dynasty, fled Kashmir after Zulju (Dulacha), a Turkic–Mongol chief, led a savage raid on Kashmir.[when?][47][48] His wife, Queen Kota Rani ruled until 1339. She is often credited for the construction of a canal, named "Kutte Kol" after her, diverting the waters of the Jhelum to prevent frequent flooding in Srinagar.[49]

During the 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni made two attempts to conquer Kashmir. However, both his campaigns failed because he could not take by siege the fortress at Lohkot.[50]

Muslim rulers

Prelude and Kashmir Sultanate (1346–1580s)

Historian Mohibbul Hasan states that the oppressive taxation, corruption, internecine fights and rise of feudal lords (Damaras) during the unpopular rule of the Lohara dynasty (1003–1320 CE) paved the way for foreign invasions of Kashmir.[51] Rinchana was a Tibetan Buddhist refugee in Kashmir, who had established himself as the ruler after Zulju.[52][47] Rinchana's conversion to Islam is a subject of Kashmiri folklore. He was persuaded to accept Islam by his minister Shah Mir, probably for political reasons. Islam had penetrated into countries outside Kashmir and in absence of the support from Hindus, who were in a majority,[53] Rinchana needed the support of the Kashmiri Muslims.[52] Shah Mir's coup on Rinchana's successor secured Muslim rule and the rule of his dynasty in Kashmir.[53]

In the 14th century, Islam gradually became the dominant religion in Kashmir.[54] With the fall of Kashmir, a premier center of Sanskrit literary creativity, Sanskrit literature there disappeared.[55][56]: 397–398 Islamic preacher Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani, who is traditionally revered by Hindus as Nund Rishi, combined elements of Kashmir Shaivism with Sufi mysticism in his discourses.[57] The Sultans between 1354 and 1470 CE were tolerant of other religions with the exception of Sultan Sikandar (1389–1413 CE). Sultan Sikandar imposed taxes on non–Muslims, forced conversions to Islam, and earned the title But–Shikan for destroying idols.[47] Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (c. 1420–1470 CE) invited artists and craftsmen from Central Asia and Persia to train local artists in Kashmir. Under his rule the arts of wood carving, papier-mâché, shawls and carpets weaving prospered.[58] For a brief period in the 1470s, states of Jammu, Poonch and Rajauri which paid tributes to Kashmir revolted against the Sultan Hajji Khan. However, they were subjugated by his son Hasan Khan who took over as ruler in 1472 CE.[58] By the mid 16th century, Hindu influence in the courts and role of the Hindu priests had declined as Muslim missionaries immigrated into Kashmir from Central Asia and Persia, and Persian replaced Sanskrit as the official language. Around the same period, the nobility of Chaks had become powerful enough to unseat the Shah Mir dynasty.[58]

Mughal general Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, a member of ruling family in Kashgar, invaded Kashmir in c. 1540 CE on behalf of emperor Humayun.[47][59] Persecution of Shias, Shafi'is and Sufis and instigation by Suri kings led to a revolt which overthrew Dughlat's rule in Kashmir.[60][59]

Mughals (1580s–1750s)

Kashmir did not witness direct Mughal rule until the reign of Mughal emperor Akbar the Great, who took control of Kashmir and added it to his Kabul Subah in 1586. Shah Jahan carved it out as a separate subah (imperial top-level province), with seat at Srinagar. During successive Mughal emperors many celebrated gardens, mosques and palaces were constructed. Religious intolerance and discriminatory taxation reappeared when Mughal emperor Aurangzeb ascended to the throne in 1658 CE. After his death, the influence of the Mughal Empire declined.[47][59]

In 1700 CE, a servant of a wealthy Kashmir merchant brought Mo-i Muqqadas (the hair of the Prophet), a relic of Muhammad, to the valley. The relic was housed in the Hazratbal Shrine on the banks of Dal Lake.[61] Nadir Shah's invasion of India in 1738 CE further weakened Mughal control over Kashmir.[61]

Durrani Empire (1752–1819)

Taking advantage of the declining Mughal Empire, the Afghan Durrani Empire under Ahmad Shah Durrani took control of Kashmir in 1752.[62] In the mid-1750s the Afghan-appointed governor of Kashmir,[63] Sukh Jiwan Mal, rebelled against the Durrani Empire before being defeated in 1762.[63][64] After Mal's defeat, the Durrani engaged in the oppression of the remaining Hindu population through forced conversions, killings, and forced labor.[64] Repression by the Durrani extended to all classes, regardless of religion, and a heavy tax burden was levied on the Kashmiri populace.[65]

A number of Afghan governors administered the region on behalf of the Durrani Empire. During the Durrani rule in Kashmir, income from the region constituted a large part of the Durrani Empire's revenue.[66] The empire controlled Kashmir until 1819, after which the region was annexed by the Sikh Empire.[67]

Sikh rule (1820–1846)

After four centuries of Muslim rule, Kashmir fell to the conquering armies of the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh of Punjab after the Battle of Shopian in 1819.[68] As the Kashmiris had suffered under the Afghans, they initially welcomed the new Sikh rulers.[69] However, the Sikh governors turned out to be hard taskmasters, and Sikh rule was generally considered oppressive,[70] protected perhaps by the remoteness of Kashmir from the capital of the Sikh Empire in Lahore.[71] The Sikhs enacted a number of anti-Muslim laws,[71] which included handing out death sentences for cow slaughter,[69] closing down the Jamia Masjid in Srinagar, and banning the azaan, the public Muslim call to prayer.[71] Kashmir had also now begun to attract European visitors, several of whom wrote of the abject poverty of the vast Muslim peasantry and of the exorbitant taxes under the Sikhs. High taxes, according to some contemporary accounts, had depopulated large tracts of the countryside, allowing only one-sixteenth of the cultivable land to be cultivated.[69] However, after a famine in 1832, the Sikhs reduced the land tax to half the produce of the land and also began to offer interest-free loans to farmers; Kashmir became the second highest revenue earner for the Sikh empire. During this time Kashmiri shawls became known worldwide, attracting many buyers especially in the west.[71]

Earlier, in 1780, after the death of Ranjit Deo, the kingdom of Jammu (to the south of the Kashmir valley) was also captured by the Sikhs and made a tributary.[68] Ranjit Deo's grandnephew, Gulab Singh, subsequently sought service at the court of Ranjit Singh, distinguished himself in later campaigns and got appointed as the Raja of Jammu in 1820. With the help of his officer, Zorawar Singh, Gulab Singh soon captured for the Sikhs the lands of Ladakh and Baltistan.[68]

Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu (Dogra Rule, 1846–1947)

In 1845, the First Anglo-Sikh War broke out, and Gulab Singh "contrived to hold himself aloof until the battle of Sobraon (1846), when he appeared as a useful mediator and the trusted advisor of Sir Henry Lawrence. Two treaties were concluded. By the first the State of Lahore (i.e. West Punjab) handed over to the British, as equivalent for (rupees) ten million of indemnity, the hill countries between Beas and Indus; by the second[72] the British made over to Gulab Singh for (Rupees) 7.5 million all the hilly or mountainous country situated to the east of Indus and west of Ravi" (i.e. the Vale of Kashmir).[68] The Treaty of Amritsar freed Gulab Singh from obligations towards the Sikhs and made him the Maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir.[73] The Dogras' loyalty came in handy to the British during the revolt of 1857 which challenged British rule in India. Dogras refused to provide sanctuary to mutineers, allowed English women and children to seek asylum in Kashmir and sent Kashmiri troops to fight on behalf of the British. British in return rewarded them by securing the succession of Dogra rule in Kashmir.[74] Soon after Gulab Singh's death in 1857,[73] his son, Ranbir Singh, added the emirates of Hunza, Gilgit and Nagar to the kingdom.[75]

The Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu (as it was then called) was constituted between 1820 and 1858 and was "somewhat artificial in composition and it did not develop a fully coherent identity, partly as a result of its disparate origins and partly as a result of the autocratic rule which it experienced on the fringes of Empire."[76] It combined disparate regions, religions, and ethnicities: to the east, Ladakh was ethnically and culturally Tibetan and its inhabitants practised Buddhism; to the south, Jammu had a mixed population of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs; in the heavily populated central Kashmir valley, the population was overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim, however, there was also a small but influential Hindu minority, the Kashmiri brahmins or pandits; to the northeast, sparsely populated Baltistan had a population ethnically related to Ladakh, but which practised Shi'a Islam; to the north, also sparsely populated, Gilgit Agency, was an area of diverse, mostly Shi'a groups; and, to the west, Punch was Muslim, but of different ethnicity than the Kashmir valley.[76]

Despite being in a majority the Muslims were made to suffer severe oppression under Hindu rule in the form of high taxes, unpaid forced labor and discriminatory laws.[77] Many Kashmiri Muslims migrated from the Valley to Punjab due to famine and policies of Dogra rulers.[78] The Muslim peasantry was vast, impoverished and ruled by a Hindu elite.[79][80] The Muslim peasants lacked education, awareness of rights and were chronically in debt to landlords and moneylenders,[79] and did not organize politically until the 1930s.[80]

1947

Ranbir Singh's grandson Hari Singh, who had ascended the throne of Kashmir in 1925, was the reigning monarch in 1947 at the conclusion of British rule of the subcontinent and the subsequent partition of the British Indian Empire into the newly independent Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan. An internal revolt began in the Poonch region against oppressive taxation by the Maharaja.[81] In August, Maharaja's forces fired upon demonstrations in favour of Kashmir joining Pakistan, burned whole villages and massacred innocent people.[82] The Poonch rebels declared an independent government of "Azad" Kashmir on 24 October.[83] Rulers of Princely States were encouraged to accede their States to either Dominion – India or Pakistan, taking into account factors such as geographical contiguity and the wishes of their people. In 1947, Jammu and Kashmir's population was "77% Muslim and 20% Hindu".[84] To postpone making a hurried decision, the Maharaja signed a standstill agreement with Pakistan, which ensured continuity of trade, travel, communication, and similar services between the two. Such an agreement was pending with India.[85] Following huge riots in Jammu, in October 1947, Pashtuns from Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province recruited by the Poonch rebels, invaded Kashmir, along with the Poonch rebels, allegedly incensed by the atrocities against fellow Muslims in Poonch and Jammu. The tribesmen engaged in looting and killing along the way.[86][87] The ostensible aim of the guerilla campaign was to frighten Hari Singh into submission. Instead the Maharaja appealed to the Government of India for assistance, and the Governor-General Lord Mountbatten[c] agreed on the condition that the ruler accede to India.[84] Once the Maharaja signed the Instrument of Accession, Indian soldiers entered Kashmir and drove the Pakistani-sponsored irregulars from all but a small section of the state. India accepted the accession, regarding it provisional[88] until such time as the will of the people can be ascertained. Kashmir leader Sheikh Abdullah endorsed the accession as ad hoc which would be ultimately decided by the people of the State. He was appointed the head of the emergency administration by the Maharaja.[89] The Pakistani government immediately contested the accession, suggesting that it was fraudulent, that the Maharaja acted under duress and that he had no right to sign an agreement with India when the standstill agreement with Pakistan was still in force.

Post-1947

In early 1948, India sought a resolution of the Kashmir conflict at the United Nations. Following the set-up of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP), the UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on 21 April 1948. The UN mission insisted that the opinion of people of J&K must be ascertained. The then Indian Prime Minister is reported to have himself urged U.N. to poll Kashmir and on the basis of results Kashmir's accession will be decided.[90] However, India insisted that no referendum could occur until all of the state had been cleared of irregulars.[84]

On 5 January 1949, UNCIP (United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan) resolution stated that the question of the accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir to India or Pakistan will be decided through a free and impartial plebiscite.[91] As per the 1948[92] and 1949 UNCIP Resolutions, both countries accepted the principle, that Pakistan secures the withdrawal of Pakistani intruders followed by withdrawal of Pakistani and Indian forces, as a basis for the formulation of a Truce agreement whose details are to be arrived in future, followed by a plebiscite; However, both countries failed to arrive at a Truce agreement due to differences in interpretation of the procedure for and extent of demilitarisation one of them being whether the Azad Kashmiri army of Pakistan is to be disbanded during the truce stage or the plebiscite stage.[93]

In the last days of 1948, a ceasefire was agreed under UN auspices; however, since the plebiscite demanded by the UN was never conducted, relations between India and Pakistan soured,[84] and eventually led to three more wars over Kashmir in 1965, 1971 and 1999. India has control of about half the area of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan controls a third of the region, governing it as Gilgit–Baltistan and Azad Kashmir. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, "Although there was a clear Muslim majority in Kashmir before the 1947 partition and its economic, cultural, and geographic contiguity with the Muslim-majority area of the Punjab (in Pakistan) could be convincingly demonstrated, the political developments during and after the partition resulted in a division of the region. Pakistan was left with territory that, although basically Muslim in character, was thinly populated, relatively inaccessible, and economically underdeveloped. The largest Muslim group, situated in the Valley of Kashmir and estimated to number more than half the population of the entire region, lay in Indian-administered territory, with its former outlets via the Jhelum valley route blocked."[94]

The UN Security Council on 20 January 1948 passed Resolution 39 establishing a special commission to investigate the conflict. Subsequent to the commission's recommendation the Security Council, ordered in its Resolution 47, passed on 21 April 1948 that the invading Pakistani army retreat from Jammu & Kashmir and that the accession of Kashmir to either India or Pakistan be determined in accordance with a plebiscite to be supervised by the UN. In a string of subsequent resolutions the Security Council took notice of the continuing failure by India to hold the plebiscite. However, no punitive action against India could be taken by the Security Council because its resolution, requiring India to hold a Plebiscite, was non-binding. Moreover, the Pakistani army never left the part of the Kashmir, they managed to keep occupied at the end of the 1947 war. They were required by the Security Council resolution 47 to remove all armed personnels from the Azad Kashmir before holding the plebiscite.[95]

The eastern region of the erstwhile princely state of Kashmir has also been beset with a boundary dispute. In the late 19th- and early 20th centuries, although some boundary agreements were signed between Great Britain, Afghanistan and Russia over the northern borders of Kashmir, China never accepted these agreements, and the official Chinese position did not change with the communist revolution in 1949. By the mid-1950s the Chinese army had entered the north-east portion of Ladakh.:[94] "By 1956–57 they had completed a military road through the Aksai Chin area to provide better communication between Xinjiang and western Tibet. India's belated discovery of this road led to border clashes between the two countries that culminated in the Sino-Indian war of October 1962."[94] China has occupied Aksai Chin since 1962 and, in addition, an adjoining region, the Trans-Karakoram Tract was ceded by Pakistan to China in 1965.

In 1949, the Indian government obliged Hari Singh to leave Jammu and Kashmir and yield the government to Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of a popular political party, the National Conference Party.[85] Since then, a bitter enmity has been developed between India and Pakistan and three wars have taken place between them over Kashmir. The growing dispute over Kashmir and the consistent failure of democracy[96] also led to the rise of Kashmir nationalism and militancy in the state.

In 1986, the Anantnag riots broke out after the CM Gul Shah ordered the construction of a mosque at the site of a Hindu Temple in Jammu and Gul Shah made an incendiary speech.[97] Hindu-Muslim riots (a reaction to the opening of Babri Masjid to Hindu worshippers) were a national event, taking place in seven other states as well.[98] Following the 1987 Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly election that were widely perceived to have been rigged, disgruntled Kashmiri youth such as the so-called 'HAJY group' – Abdul Hamid Shaikh, Ashfaq Majid Wani, Javed Ahmed Mir and Mohammed Yasin Malik – joined the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front(JKLF) as an alternative to the ineffective democratic setup that was prevalent in Kashmir. This led to gain in the momentum of the popular insurgency in the Kashmir Valley.[99][100] The year 1989 saw the intensification of conflict in Jammu and Kashmir as Mujahadeens from Afghanistan slowly infiltrated the region following the end of the Soviet–Afghan War the same year.[101] Pakistan provided arms and training to both indigenous and foreign militants in Kashmir, thus adding fuel to the smouldering fire of discontent in the valley.[102][103][104]

In August 2019, the Government of India repealed the special status accorded to Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Indian constitution in 2019, and the Parliament of India passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, which contained provisions to dissolve the state and reorganise it into two union territories – Jammu and Kashmir in the west and Ladakh in the east.[105] These changes came into effect from 31 October 2019.

Historical demographics of Kashmir

In the 1901 Census of the British Indian Empire, the population of the princely state of Kashmir was 2,905,578. Of these 2,154,695 were Muslims, 689,073 Hindus, 25,828 Sikhs, and 35,047 Buddhists. The Hindus were found mainly in Jammu, where they constituted a little less than 50% of the population.[106] In the Kashmir Valley, the Hindus represented "only 524 in every 10,000 of the population (i.e. 5.24%), and in the frontier wazarats of Ladhakh and Gilgit only 94 out of every 10,000 persons (0.94%)."[106] In the same Census of 1901, in the Kashmir Valley, the total population was recorded to be 1,157,394, of which the Muslim population was 1,083,766, or 93.6% of the population.[106] These percentages have remained fairly stable for the last 100 years.[107] In the 1941 Census of British India, Muslims accounted for 93.6% of the population of the Kashmir Valley and the Hindus constituted 4%.[107] In 2003, the percentage of Muslims in the Kashmir Valley was 95%[108] and those of Hindus 4%; the same year, in Jammu, the percentage of Hindus was 67% and those of Muslims 27%.[108]

Among the Muslims of the Kashmir province within the princely state, four divisions were recorded: "Shaikhs, Saiyids, Mughals, and Pathans. The Shaikhs, who are by far the most numerous, are the descendants of Hindus, but have retained none of the caste rules of their forefathers. They have clan names known as krams ..."[109] It was recorded that these kram names included "Tantre", "Shaikh", "Bat", "Mantu", "Ganai", "Dar", "Damar", "Lon", etc. The Saiyids, it was recorded, "could be divided into those who follow the profession of religion and those who have taken to agriculture and other pursuits. Their kram name is 'Mir.' While a Saiyid retains his saintly profession Mir is a prefix; if he has taken to agriculture, Mir is an affix to his name."[109] The Mughals who were not numerous were recorded to have kram names like "Mir" (a corruption of "Mirza"), "Beg", "Bandi", "Bach" and "Ashaye". Finally, it was recorded that the Pathans "who are more numerous than the Mughals, ... are found chiefly in the south-west of the valley, where Pathan colonies have from time to time been founded. The most interesting of these colonies is that of Kuki-Khel Afridis at Dranghaihama, who retain all the old customs and speak Pashtu."[109] Among the main tribes of Muslims in the princely state are the Butts, Dar, Lone, Jat, Gujjar, Rajput, Sudhan and Khatri. A small number of Butts, Dar and Lone use the title Khawaja and the Khatri use the title Shaikh the Gujjar use the title of Chaudhary. All these tribes are indigenous of the princely state which converted to Islam from Hinduism during its arrival in region.

Among the Hindus of Jammu province, who numbered 626,177 (or 90.87% of the Hindu population of the princely state), the most important castes recorded in the census were "Brahmans (186,000), the Rajputs (167,000), the Khattris (48,000) and the Thakkars (93,000)."[106]

Gallery

-

Pot, excavated from Burzahom (c. 2700 BCE), depicts horned motifs, which suggest links with sites like Kot-Diji, in Sindh.

-

A Muslim shawl making family in Kashmir. 1867. Cashmere shawl manufactory, chromolith., William Simpson.

-

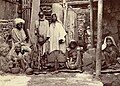

Kashmiri home life c. 1890. Photographer unknown.

-

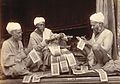

Muslim papier-mâché ornament painters in Kashmir. 1895. Photographer: unknown.

-

Three Hindu priests writing religious texts. 1890s, Jammu and Kashmir, photographer: unknown.

-

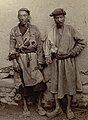

Full-length portrait of two Ladakhi men. 1895, Ladakh, unknown photographer.

See also

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 47

- Kashmiriyat

- Sharada Peeth

- Buddhism in Kashmir

- Harsha of Kashmir

- List of topics on the land and the people of "Jammu and Kashmir"

Notes

- ^ Puranic genealogy are "incomplete and occasionally inaccurate". The chronology of events described in Puranas often do not tally with historical discoveries of modern era.

- ^ Formally, "Abisares" was the ruler of Abhisaras, the people of the Poonch and Rajouri districts. Historian P. N. K. Bamzai believes his domain included Kashmir.[21]

- ^ Viscount Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India, stayed on in independent India from 1947 to 1948, serving as the first Governor-General of an independent India.

References

- ^ Christopher Snedden (15 September 2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Hurst. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84904-622-0.

- ^ Dhar, Somnath (1986), Jammu and Kashmir folklore, Marwah Publications, p. 8, ISBN 9780836418095

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Holdich, Thomas Hungerford (1911). "Kashmir". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 688.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain (2003) [first published in French, L'Histoire de l'Inde, Fayard, 1971], A Brief History of India, translated by Hurry, Kenneth, Inner Traditions / Bear & Co, pp. 65–, ISBN 978-1-59477-794-3

- ^ Houtsma 1993, p. 792.

- ^ Kenoyer & Heuston 2005, p. 28.

- ^ a b Sharma 2005, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Singh 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Sreedharan 2004, p. 330.

- ^ Sharma 2005, p. 73–4.

- ^ Sharma 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Sharma 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Hasan 1983, p. 47.

- ^ Bhat, Ghulam M.; Ashton, Nick; Parfitt, Simon; Jukar, Advait; Dickinson, Marc R.; Thusu, Bindra; Craig, Jonathan (October 2024). "Human exploitation of a straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon) in Middle Pleistocene deposits at Pampore, Kashmir, India". Quaternary Science Reviews. 342: 108894. Bibcode:2024QSRv..34208894B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108894.

- ^ Jukar, Advait M.; Bhat, Ghulam; Parfitt, Simon; Ashton, Nick; Dickinson, Marc; Zhang, Hanwen; Dar, A. M.; Lone, M. S.; Thusu, Bindra; Craig, Jonathan (11 October 2024). "A remarkable Palaeoloxodon (Mammalia, Proboscidea) skull from the intermontane Kashmir Valley, India". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2396821. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Singh 2008, pp. 111–3.

- ^ Kennedy 2000, p. 259.

- ^ Allchin & Allchin 1982, p. 113.

- ^ Rapson 1955, p. 118.

- ^ Sharma 1985, p. 44.

- ^ Bamzai 1994, p. 68.

- ^ Heckel 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Green 1970, p. 403.

- ^ Sastri 1988, p. 219.

- ^ Chatterjee 1998, p. 199.

- ^ Bamzai 1994, pp. 83–4.

- ^ Pal 1989, p. 51.

- ^ Singh 2008, pp. 522–3.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 480.

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 71.

- ^ Dani 1999, pp. 142–3.

- ^ Haywood 1998, p. 3.2.

- ^ Harold Miles Tanner (13 March 2009). China: A History. Hackett Publishing. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-0-87220-915-2.

- ^ Harold Miles Tanner (12 March 2010). China: A History: Volume 1: From Neolithic cultures through the Great Qing Empire 10,000 BCE–1799 CE. Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-1-60384-202-0.

- ^ H. J. Van Derven (1 January 2000). Warfare in Chinese History. BRILL. pp. 122–. ISBN 90-04-11774-1.

- ^ René Grousset (January 1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- ^ "Kashmir: region, Indian subcontinent". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 May 2022. Quote: "A succession of Hindu dynasties ruled Kashmir until 1346, when it came under Muslim rule."

- ^ Pal 1989, p. 52.

- ^ Flood 1996, pp. 166–7.

- ^ Flood 2008, p. 213.

- ^ a b c d Singh 2008, p. 571.

- ^ Majumdar 1977, pp. 260–3.

- ^ Wink 1991, pp. 242–5.

- ^ Majumdar 1977, p. 356.

- ^ Majumdar 1977, p. 357.

- ^ Khan 2008, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e Chadha 2005, p. 38.

- ^ Hasan 1959, pp. 35–6.

- ^ Culture and political history of Kashmir, Prithivi Nath Kaul Bamzai, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., 1994.

- ^ Frye 1975, p. 178.

- ^ Hasan 1959, pp. 32–4.

- ^ a b Asimov & Bosworth 1998, p. 308.

- ^ a b Asimov & Bosworth 1998, p. 309.

- ^ Downey, Tom (5 October 2015). "Explore the Beauty of Kashmir". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Hanneder, J. (2002). "On 'The Death of Sanskrit'". Indo-Iranian Journal. 45 (4): 293–310. doi:10.1163/000000002124994847. JSTOR 24664154. S2CID 189797805.

- ^ Pollock, Sheldon (2001). "The Death of Sanskrit". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 43 (2): 392–426. doi:10.1017/s001041750100353x (inactive 1 November 2024). S2CID 35550166.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Bose 2005, pp. 268–9.

- ^ a b c Asimov & Bosworth 1998, p. 313.

- ^ a b c Houtsma 1993, p. 793.

- ^ Hasan 1983, p. 48.

- ^ a b Schofield 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. pp. 43, 44. ISBN 978-1-84904-342-7.

- ^ a b Banga, Indu (1967). "Ahmad Shah Abdali's Designs over the Punjab". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 29: 185–190. JSTOR 44155495.

- ^ a b Dhar, Triloki Nath (2004). Saints and Sages of Kashmir. APH Publishing. p. 232. ISBN 978-81-7648-576-0.

- ^ Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging; Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 35.

- ^ Rubin, Barnett R. (1988). "Lineages of the State in Afghanistan". Asian Survey. 28 (11): 1188–1209. doi:10.2307/2644508. JSTOR 2644508.

- ^ Zaidi, S. H. (2003). "The Intractable Kashmir Issue: Search for a Rational Solution". Pakistan Horizon. 56 (2): 53–85. JSTOR 41394023.

- ^ a b c d The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Volume 15), pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c Schofield 2010, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Madan 2008, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Zutshi 2003, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Treaty of Amritsar 1846.

- ^ a b Schofield 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Schofield 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Schofield 2010, p. 11.

- ^ a b Bowers, Paul. 2004. "Kashmir." Research Paper 4/28 Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, International Affairs and Defence, House of Commons Library, United Kingdom.

- ^ Kashmir. OUP. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018.

- ^ Iqbal Singh Sevea (29 June 2012). The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism in Late Colonial India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-139-53639-4.

- ^ a b Bose 2005, pp. 15–17

- ^ a b Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 54

- ^ Prem Nath Bazaz, "The Truth About Kashmir"

- ^ Official Records of the United Nations Security Council, Meeting No:234, 1948, pp.250–1:[1]

- ^ 1947 Kashmir History

- ^ a b c d Stein 1998, p. 368.

- ^ a b Schofield, Victoria. 'Kashmir: The origins of the dispute', BBC News UK Edition (16 January 2002) Retrieved 20 May 2005

- ^ Jamal, Arif (2009), Shadow War: The Untold Story of Jihad in Kashmir, Melville House, pp. 52–53, ISBN 978-1-933633-59-6

- ^ Pathan Tribal Invasion into Kashmir

- ^ Govt. of India, White Paper on Jammu & Kashmir, Delhi 1948, p.77

- ^ Sheikh Abdullah, Flames of the Chinar, New Delhi, 1993, p.97

- ^ "NEHRU URGES U.N. TO POLL KASHMIR; Would Have Supervised Ballot to Decide Accession – Bomb Attack by India Reported". The New York Times. 3 November 1947. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ UNCIP Resolution, 5 January 1949.

- ^ UNCIP Resolution, 13 August 1948.

- ^ UNCIP Resolution, 30 March 1951.

- ^ a b c "Kashmir." (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 March 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Resolution 47 (1948).

- ^ Elections in Kashmir

- ^ Verma, P. S. (1994). Jammu and Kashmir at the Political Crossroads. Vikas Publishing House. p. 214. ISBN 9780706976205.

- ^ "Hindu-Moslem riots reported in Kashmir, Calcutta". Associated Press News. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Puri 1993, p. 52.

- ^ 1989 Insurgency

- ^ BBC Timeline on Kashmir conflict.

- ^ Human Rights Watch Report, 1994

- ^ Pakistan admission over Kashmir

- ^ See Operation Tupac

- ^ "Jammu Kashmir Article 370: Govt revokes Article 370 from Jammu and Kashmir, bifurcates state into two Union Territories". The Times of India. Ist. 5 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Volume 15), pp. 99–102.

- ^ a b Rai 2004, p. 27.

- ^ a b BBC. 2003. The Future of Kashmir? In Depth.

- ^ a b c Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 15. 1908. Oxford University Press, Oxford and London. pp. 99–102.

Bibliography

- Allchin, Bridget; Allchin, Raymond (1982), The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-28550-6

- Asimov, M S; Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1998), Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, UNESCO, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1

- Bamzai, P. N. K (1994), Culture And Political History of Kashmir ( 3 Vols. Set), M.D. Publications, ISBN 978-81-85880-31-0

- Bose, Sumantra (2005), Kashmir: Roots of Conflict Paths To Peace, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02855-5

- Chadha, Vivek (2005), Low Intensity Conflicts in India: An Analysis, SAGE, ISBN 978-0-7619-3325-0

- Chatterjee, Suhas (1998), Indian Civilization And Culture, M.D. Publications, ISBN 978-81-7533-083-2

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1999), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1540-7

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0

- Flood, Gavin D. (2008), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, Wiley, ISBN 978-81-265-1629-2

- Frye, R. N. (1975), The Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6

- Green, Peter (1970), Alexander of Macedon: 356-323 B.c. : a Historical Biography, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07166-7

- Grousset, René (1970), The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1

- Guha, Ramachandra (2011), India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy, Pan Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-330-54020-9

- Hasan, Mohibbul (1959), Kashmīr Under the Sultāns, Aakar Books, ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Heckel, Waldemar (2003), The Wars of Alexander the Great 336–323 BC, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-203-49959-7

- Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1993), E.J. Brill's First Encyclopedia of Islam, 1913–1936, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-09790-2

- Kennedy, Kenneth A. R. (2000), God-Apes and Fossil Men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-11013-1

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark; Heuston, Kimberly Burton (2005), The Ancient South Asian World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-522243-2

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8

- Madan, T. N. (2008), "Kashmir, Kashmiris, Kashmiriyat: An Introductory Essay", in Rao, Aparna (ed.), The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture?, Delhi: Manohar. Pp. xviii, 758, pp. 1–36, ISBN 978-81-7304-751-0

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977), Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1989), Indian Sculpture: 700–1800, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06477-5

- Puri, Balraj (1993), Kashmir towards insurgency, Orient Longman, ISBN 978-0-86311-384-0

- Rai, Mridu (2004), Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-85065-661-6

- Rapson, Edward James (1955), The Cambridge History of India, Cambridge University Press, GGKEY:FP2CEFT2WJH

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1988), Age of the Nandas And Mauryas, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1

- Schofield, Victoria (2010), Kashmir in conflict: India, Pakistan and the unending war, I. B. Tauris., ISBN 978-1-84885-105-4

- Sharma, Subhra (1985), Life in the Upanishads, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-202-4

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Stein, B. (1998), A History of India (1st ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-20546-3

- Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009), The Partition of India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-76177-2

- Wink, André (1991), Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-09509-0

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2003), Language of belonging: Islam, regional identity, and the making of Kashmir, Oxford University Press/Permanent Black, ISBN 978-0-19-521939-5

Primary sources

- Muḥammad, A. K., & Pandit, K. N. (2009). A Muslim missionary in mediaeval Kashmir: Being the English translation of Tohfatu'l-ahbab. New Delhi: Voice of India.

- Pandit, K. N. (2013). Baharistan-i-shahi: A chronicle of mediaeval Kashmir. Srinagar: Gulshan Books.

- The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Volume 15); Karachi to Kotayam, Great Britain Commonwealth Office, 1908, ISBN 978-1-154-40971-0

- Resolution 47 (1948) of 21 April 1948, UN Security Council, 21 April 1948, retrieved 26 February 2013

- Treaty of Amritsar, 16 March 1846, 16 March 1846, retrieved 26 February 2013

- UNCIP Resolution, 13 August 1948, Mount Holyoke College, 10 January 1949, archived from the original on 23 February 2013, retrieved 26 February 2013

- UNCIP Resolution, 5 January 1949, Mount Holyoke College, 10 January 1949, archived from the original on 23 February 2013, retrieved 26 February 2013

- UNCIP Resolution, 30 March 1951, Mount Holyoke College, 10 January 1949, archived from the original on 23 February 2013, retrieved 26 February 2013

Historiography

- Ganguly, D.K. (1985), History and Historians in Ancient India, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-0-391-03250-7

- Ghose, D. K. (1969), "Source-Material for the History of Kashmir (Second Half of the Nineteenth Century)", Quarterly Review of Historical Studies, 9 (1): 7–12

- Hasan, Mohibbul (1983), Historians of medieval India, Meenakshi Prakashan, OCLC 12924924

- Hewitt, Vernon (2007), "Never Ending Stories: Recent Trends in the Historiography of Jammu and Kashmir", History Compass, 5 (2): 288–301, doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2006.00372.x covers 1846 to 1997

- Lone, Fozia Nazir (2009), "From âSale to Accession Deedââ Scanning the Historiography of Kashmir 1846â1947", History Compass, 7 (6): 1496–1508, doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00652.x

- Sharma, Tej Ram (2005), Historiography: A History of Historical Writing, Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-8069-155-3

- Sreedharan, E. (2004), A Textbook of Historiography: 500 BC to AD 2000, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-250-2657-0

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2012), "Whither Kashmir Studies?: A Review", Modern Asian Studies, 46 (4): 1033–1048, doi:10.1017/S0026749X11000345, S2CID 144626260

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2013), "Past as tradition, past as history: The Rajatarangini narratives in Kashmir's Persian historical tradition", The Indian Economic & Social History Review, 50 (2): 201–219, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.893.7358, doi:10.1177/0019464613487119, S2CID 143228373

External links

- Baharistan -i Shahi A Chronicle of Medieval Kashmir translated into English Archived 22 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Conflict in Kashmir: Selected Internet Resources by the Library, University of California, Berkeley, USA; Bibliographies and Web-Bibliographies list

- Kashmir Website with Historical Timeline

- Coins of the Kashmir Sultanate (1346–1586)

- (in Arabic) "The Great History of the Events of Kashmir" from 1821